1. Introduction

Pedestrians are inherently vulnerable road users, and crashes involving pedestrians frequently result in severe injuries or fatalities. Pedestrian safety remains a critical public health and transportation concern in the United States, with over 7300 pedestrians tragically killed and an estimated 68,000 injured in traffic crashes in 2023 alone [

1]. On average, in 2023, a pedestrian was killed every 72 min and injured every 8 min nationwide. Pedestrian fatalities accounted for 18% of all traffic-related deaths, while injuries to pedestrians comprised nearly 3% of all crash-related injuries, according to NHTSA [

1]. Despite some recent declines—such as a 5.4% drop in pedestrian deaths between 2022 and 2023, pedestrian fatalities remain approximately 14% higher than pre-pandemic 2019 levels [

2]. Within this national context, Tennessee stands as a state with elevated pedestrian risk. Elevated pedestrian fatality rates in Tennessee have persisted despite recent nationwide declines, and the intersection of increasing vehicle sizes, resurgence in dark-hour crashes, and shifting travel patterns post-pandemic compounds the urgency to mitigate crashes. In 2023, Tennessee ranked 13th in the nation for pedestrian fatality rate, reporting approximately 186 pedestrian deaths and a rate of about 2.61 per 100,000 population [

1]. Over the past decade, Tennessee has experienced a doubling of pedestrian fatalities—from 72 in 2009 to 156 in 2019, reflecting a rising trend in crash severity [

2]. Many studies have examined pedestrian safety, identifying a wide range of contributing factors including roadway and traffic environments (e.g., speed limits, lane count, traffic volumes, and junction type), environmental conditions (e.g., lighting, weather, and time of day), and contextual variables (e.g., urban vs. rural setting, land use, and access control), among others [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Most of the previous research has focused on broad cross-sectional analyses, with fewer studies leveraging modern machine learning techniques or predictive analytics at the state level. By correlating injury severity outcomes and crash frequency with these diverse factors, this study therefore employed GIS, neural networks, regression analysis complemented by machine learning and data analytics methodologies to explore relative contributions, interactions, and predictive patterns. The main objective is to statistically quantify how these variables relate to both the likelihood of severe injury or fatality and the incidence of pedestrian crashes in Tennessee.

The paper applies three analytical approaches—Negative Binomial (NB) regression, ANFIS, and XGBoost—as complementary tools addressing different but related research objectives within the broader theme of pedestrian crash analysis. The NB regression model is employed to quantify how roadway, traffic, and environmental variables statistically influence pedestrian crash frequency and to estimate effect directions and magnitudes. The ANFIS framework served a different purpose by examining how socioeconomic conditions at the census-block level relate to pedestrian crash burdens, capturing nonlinear interactions that traditional statistical models cannot fully express. Finally, XGBoost is used to evaluate variable importance and nonlinear influence patterns across all predictors, offering a robust machine-learning perspective to validate which factors most strongly affect crash occurrence. Together, these methods provide a multi-angle assessment: NB explains statistical significance and effect size, ANFIS captures fuzzy and nonlinear social-environmental relationships, and XGBoost identifies dominant predictors through computational learning.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Overview of Pedestrian Safety

Pedestrian safety remains a persistent challenge in urban environments globally, characterized by rising injury and fatality rates despite advancements in urban design and public policy. Results from recent global studies reveal that while infrastructure interventions—such as traffic calming and lighting—hold promise, a holistic, equity-focused approach remains essential for achieving significant reductions in pedestrian injuries and fatalities [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Across cities worldwide, pedestrian safety constitutes a critical urban health issue, with traffic crashes inflicting a substantial toll on individual well-being and public health systems. Traditionally, low speed zones are assumed to be safer for pedestrians; however, analyses indicate that substantial risks persist even within these environments [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. The problem is worsened by increasing urban density, the push for active transportation, and legacy infrastructure suited for vulnerable road users. This therefore allows pedestrian safety analysis to consider the frequency and severity of related crashes, considering built environmental features, demographic and temporal correlates, and the methodologies applied for safety assessments, which can provide comprehensive insight into factors influencing pedestrian risk in urban and rural domains [

19,

20]. Studies from diverse contexts, such as Florida and India, have documented that urban tracts with intensive commercial, mixed land uses, substantial traffic flow, high intersection density, and increased transit accessibility experience higher frequencies of pedestrian crashes. Built environment characteristics—such as sidewalk length, proximity to transit stops, lighting, and intersection configuration—strongly mediate exposure and risk [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

21,

22]. Injury severity among pedestrian crash victims demonstrates a marked association with vehicle speed, time of day, and user demographics. The nonlinear relationship between impact speed and injury risk underpins the continued advocacy for aggressive speed management in urban areas, with 20 mph zones shown to sharply reduce fatal and severe injury rates [

23].

A critical determinant of injury and crash risk is the socio-demographic and temporal context in which pedestrian activity unfolds. Literature shows that higher injury severity is associated with crash locations removed from controlled crossings, alcohol involvement by either party, and behaviors such as jaywalking or failure to adhere to road signals [

4,

5]. Nighttime and weekend crashes are significantly more likely to result in serious or fatal injury, attributed to higher vehicle speeds, diminished visibility, and alcohol prevalence. Furthermore, low-income and minority neighborhoods are consistently overrepresented in urban injury and fatality statistics, signaling a need for tailored, equity-conscious interventions [

3,

6,

24,

25,

26,

27]. High density of intersections and uncontrolled crossings fosters elevated risk, particularly when not paired with appropriate pedestrian safety treatments such as refuge medians, curb extensions, and traffic-calming infrastructure [

5,

9]. A synergy of built environment elements—including land use mix, street geometry, and traffic volume—requires locally sensitive combinations of design interventions for optimal safety [

27]. Evaluative studies consistently highlight the effectiveness of comprehensive infrastructure and policy interventions. Traffic-calming measures—such as speed humps, chicanes, and narrowed lanes—reduce vehicle speeds and pedestrian injury risk, particularly in dense urban neighborhoods [

9]. Improvements in crosswalk visibility, pedestrian-specific signalization, and nighttime lighting have been linked with reductions in collision frequency and severity. Behavioral interventions, including public awareness campaigns and targeted enforcement of existing traffic laws, supplement engineering efforts by addressing risky behaviors among both drivers and pedestrians [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9].

2.2. Modeling Pedestrian Crash Frequency

Methodologically, research employs an array of statistical and computational approaches to dissect pedestrian crash phenomena [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. One approach that has been used in analyzing crash frequency is through the count models to identify the contributing factors influencing crash occurrence. In this approach, Poisson and negative binomial regression models have been widely applied for analyzing crash frequency as count data, while spatial and kernel density estimation techniques are employed to reveal patterns and identify high-risk zones [

3,

6]. In many transportation safety studies, the negative binomial (NB) model has been preferred over the Poisson model because pedestrian crash data typically exhibit overdispersion, meaning the variance exceeds the mean [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. The Poisson model assumes equality between mean and variance, which is rarely satisfied for real-world crash counts, especially when factors such as unobserved heterogeneity or site-specific variations exist. The NB model generalizes the Poisson model by introducing an unobserved heterogeneity term (

τᵢ) that follows a gamma distribution, allowing for extra variability across observations. The expected number of pedestrian crashes at location

i, conditional on observed covariates

Xᵢ and random effect

τᵢ, is expressed as [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]:

where

Yᵢ denotes the observed crash count,

μᵢ is the mean crash frequency, and

β is a vector of parameters to be estimated. The probability of observing

Yᵢ =

yᵢ crashes, conditional on

Xᵢ and

τᵢ, follows a Poisson distribution:

When the random term

τᵢ is integrated out, the marginal distribution of

Yᵢ conditional on

Xᵢ follows a negative binomial form:

where

θ is the dispersion parameter, controlling the degree of overdispersion in the data. The conditional mean of the distribution is

μᵢ and the conditional variance is

μᵢ (1 +

αμᵢ), where

α = 1/

θ. The NB model is therefore used in this study to analyze pedestrian crash frequencies along roadway segments and at intersections, allowing for overdispersion and random variability that cannot be explained by the observed roadway, traffic, or environmental factors.

2.3. Evaluating Pedestrian Crashes by Social Economic Factors

Census distribution and mixed-methods studies combining quantitative crash data with environmental audits and field surveys are now prevalent in the field, allowing for contextualized, place-based insights [

3,

6,

7]. This study also examined how sociodemographic characteristics at the census block group level influenced pedestrian crash occurrences. The analysis employed two modeling techniques, notably the Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS), which integrates the strengths of fuzzy logic and artificial neural networks into a single hybrid framework [

36]. ANFIS has been extensively utilized in fields such as traffic safety analysis [

37,

38], healthcare modeling [

39], and power systems [

40], among others. However, its application to pedestrian crash prediction has been limited in previous research. The ANFIS model developed in this study was structured to predict pedestrian crash frequency using four input sociodemographic variables. The approach combines numerical data with linguistic representations of knowledge, allowing the model to handle both quantitative and qualitative information. ANFIS operates by using fuzzy logic to translate input variables into an output through a network of interconnected processing elements whose parameters (weights) are adaptively tuned to best represent the underlying data relationships [

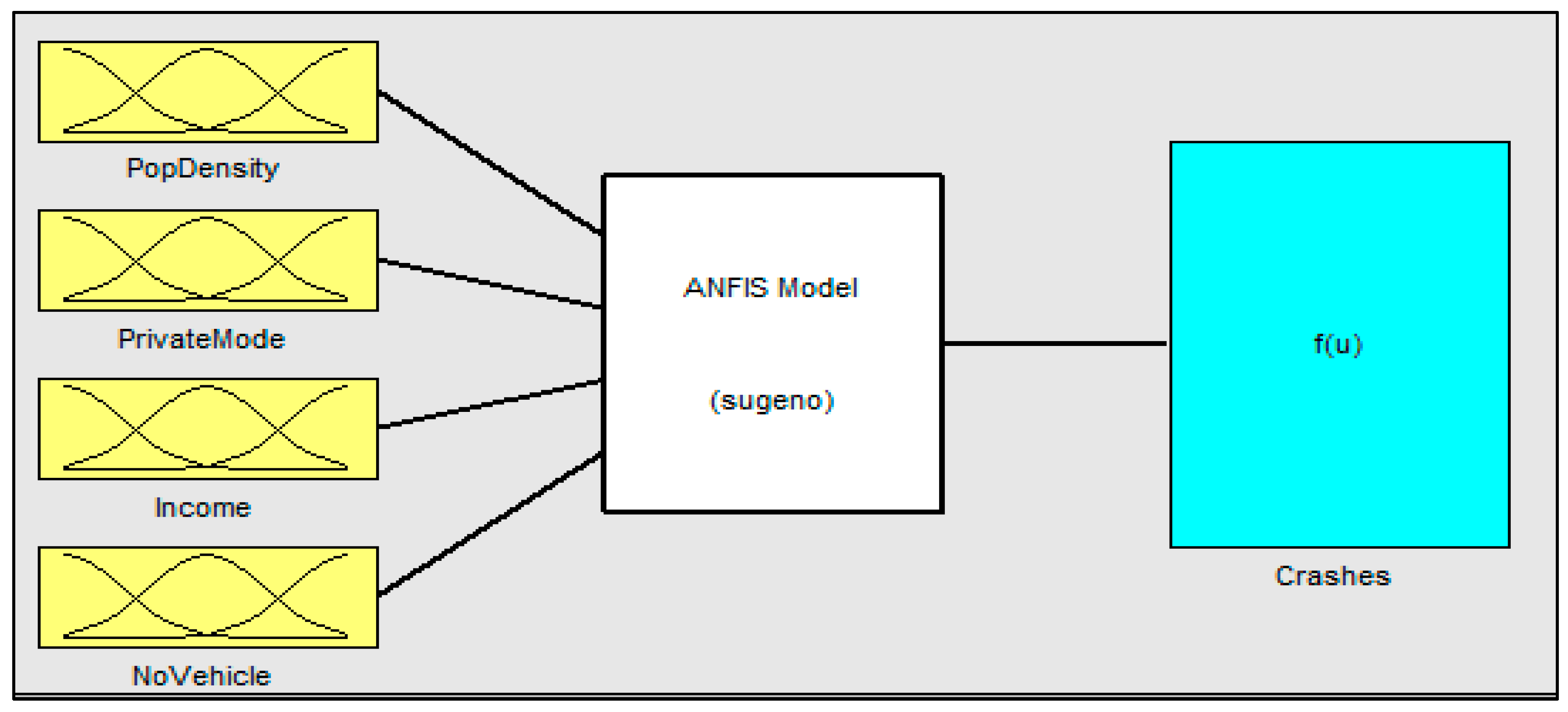

39]. These parameters correspond to membership functions and fuzzy rules that, unlike traditional fixed systems, are automatically adjusted based on observed data to reflect the true variability and uncertainty within the dataset. The neuro-adaptive learning process enables the fuzzy model to iteratively optimize its parameters using algorithms such as backpropagation or a hybrid least-squares approach, allowing the model to “learn” from empirical data and improve predictive accuracy. The purpose of the ANFIS model established in this study was to estimate how the sociodemographic attributes of a census block group affect pedestrian crash likelihood. The model was designed using a fuzzy inference system (FIS), as illustrated in

Figure 1, with four primary inputs—population density, percentage of workers commuting by private car, median household income, and percentage of housing units without a vehicle—and one output representing the total number of pedestrian crashes. Inference within this system followed a rule-based structure, using conditional statements of the form “If A, then Z” where

A and

Z are fuzzy sets. When consequents are constants or linear functions, the framework follows the Takagi–Sugeno fuzzy model type. ANFIS, therefore, represents a Sugeno-type fuzzy system, wherein such rules allow the model to efficiently capture nonlinear relationships between sociodemographic factors and pedestrian crash occurrences which can be expressed in the following form; IF

x1 is

A1 AND

x2 is

A2 …. AND

xm is

Am THEN

y =

f(

x1,

x2,

…,

xm) where

x1,

x2, …,

xm are input variables,

A1,

A2, …,

Am are fuzzy sets and

y is either a constant or a linear function of the input variables.

2.4. Evaluating Pedestrian Crashes Through Machine Learning

In addition to traditional statistical approaches, machine learning techniques have recently demonstrated superior performance in predicting crash frequency and severity due to their ability to handle complex, nonlinear relationships and large datasets. Machine learning approaches—such as decision trees, random forests, XG Boost, K-nearest neighbors (KNN), and ensemble methods—are now widely used to predict crash severity, identify key predictors, and uncover nonlinear interactions not easily detected by traditional statistical methods. Random forest and Extra Tree classifiers, for example, have achieved high accuracy (often over 95%) in classifying injury severity using large datasets with dozens of features, including vehicle and location attributes, crash circumstances, demographic factors, and environmental variables [

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46]. Deep learning techniques—particularly neural networks and frameworks like Inception-v3 and multi-task deep neural networks—have further advanced the field. One study used the Inception-v3 model, transformed traditional tabular crash data into images, and leveraged the DeepInsight technique to achieve superior prediction of crash severity compared to conventional ML and statistical methods, with overall accuracy for fatal, injury, and no-injury categories ranging from 77.5% to above 90%. Other deep learning research has focused on head injury prediction in simulated pedestrian-vehicle collisions, showing how model accuracy varies with pedestrian physique and scenario details [

47,

48,

49]. Machine learning methods have also been applied to crash frequency modeling, using boosted regression trees, XGBoost, and automated ML platforms (AutoML) to identify important contributors to crash risk such as pedestrian and vehicle volumes, land use, roadway features, and social-demographic attributes. These methods assist in extracting complex patterns and interactions with some studies finding that higher pedestrian volumes can lower crash rates, suggesting a safety-in-numbers effect [

42]. The integration of advanced sensor data, computer vision, and explainable AI frameworks is also expanding the field, both in evaluating real-world active safety technology like ADAS and in urban crash forecasting [

43]. To enhance interpretability, this study applies the SHAPley Additive explanations (SHAP) method to visualize the results of the XG Boost model. SHAP helps to illustrate relative importance and contribution of each feature in the model, offering a transparent understanding of how different factors influence crash frequency and severity [

50].

3. Study Data

This study utilizes pedestrian crash records obtained from the Tennessee Department of Transportation (TDOT) through the eTRIMS database. The dataset consists of 18,565 crash records involving pedestrians reported between 2002 and 2025. The dataset comprised both categorical and continuous variables representing roadway, environmental, and operational characteristics associated with pedestrian crashes,

Table 1a,b. The categorical variables included posted speed limit (15–35 mph or 40–45 mph), relation to junction (non-junction or junction-related), urban/rural classification (unknown, rural, urban), terrain type (flat, rolling, mountainous), weather condition (clear/good or unclear/bad), land use (rural, commercial/CBD, residential), street lighting presence, location (on travel way or others), lighting condition (light or dark), and time of day (daylight or night). The continuous variables included number of crashes as response variable, total pedestrians killed, total pedestrians injured, AADT, directional split, percentage of passenger cars, percentage of trucks, and number of lanes. Together, these variables provided a comprehensive representation of the roadway environment, traffic exposure, and contextual conditions influencing pedestrian crash frequency and severity across Tennessee roadways. Each record captures a comprehensive set of variables—including injury severity, crash frequency, time-of-day, lighting and street-light conditions, posted speed, lane configurations, Average Annual Daily Traffic (AADT), functional class, urban/rural classification, junction relation, weather, and land use. The data also include other variables describing crash outcomes, roadway and traffic characteristics, temporal distributions, and environmental conditions. Among all pedestrian crashes, 54.0% resulted in minor injury, 10.3% in possible injury, 20.4% in suspected serious injury, and 8.5% in fatalities. Crashes are distributed unevenly across days of the week, with 76.5% occurring on weekdays and 23.5% on weekends. Time-of-day coding shows a strong evening concentration: 29.4% of crashes occurred between 6:00 p.m. and 9:00 p.m., and the single highest crash hour was 6:00 p.m. Morning peaks are also present, but evening hours consistently carry the largest share of pedestrian crash records,

Figure 1. This breadth of information allowed this study to conduct a detailed and multifaceted examination of pedestrian crash patterns as presented in this paper.

4. Pedestrian Crashes Digested by Day/Night, Dark/Light Conditions

Understanding how lighting and time of day influence pedestrian crashes is essential for identifying when and where pedestrians are most vulnerable. Visibility, driver perception, and pedestrian behavior vary dramatically between daylight and darkness, shaping both the frequency and severity of crash outcomes. Previous research consistently shows that crashes occurring during nighttime or in dark, poorly illuminated conditions are far more likely to result in serious or fatal injuries compared with those in daylight [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. In Tennessee, roadway environments range from high-speed rural to dense urban corridors, these lighting and temporal factors interact with roadway design, traffic, speed, and land use to influence pedestrian safety.

4.1. Correlation of Pedestrian Crashes by Lighting and Time of Day

Using 18,565 pedestrian-involved crashes, the light-environment split is nearly even (Dark: 9461; Daylight: 9104), whereas day/night shows more crashes by day (Day: 11,105) than night (Night: 7460). Despite fewer nighttime events, the burden of harm is concentrated at night and in darkness. In the dark/light view, darkness is associated with 1315 pedestrian fatalities and 8324 injuries, versus 279 fatalities and 8644 injuries in daylight; the severe-outcome share (serious injury or fatal) is 37.9% in Dark and 19.5% in Daylight. The day/night split tells the same story: Night accounts for 1052 fatalities and 6562 injuries (severe share 38.6%), compared with 542 fatalities and 10,406 injuries by Day (severe share 22.4%). Means of context variables move in the same direction: night crashes occur on slightly higher-speed facilities (mean posted speed ≈ 37.8 mph at Night vs. ≈36.9 mph by Day) and marginally higher-volume corridors (mean AADT ≈ 15,848 at Night vs. ≈14,950 by Day), with similar vehicle involvement (≈1.03 vehicles/crash across both). Speed and light interact strongly. With posted speed limits coded (0 = ≤35 mph; 1 = 40–45 mph), the severe-outcome rate rises at higher posted speeds both by day (19.7% at ≤35 mph vs. 25.1% at 40–45 mph) and at night (30.5% at ≤35 mph vs. 44.8% at 40–45 mph). Nighttime crashes also skew more toward higher-speed corridors (56.3% of Night crashes on 40–45 mph vs. 50.1% by Day). Fatality means reflect this: at Night, mean fatalities per crash are 0.19 on 40–45 mph segments vs. 0.08 at ≤35 mph; by Day the corresponding means are 0.07 and 0.03. Higher-speed sites also carry higher mean AADT (e.g., ≈18,792 at Night on 40–45 mph vs. ≈12,052 at ≤35 mph), suggesting that nighttime risk concentrates on busier, faster corridors. Total-injury vary less with speed by Day (≈0.94 regardless of category), but at Night injury means are lower on 40–45 mph (≈0.83) while fatalities rise—consistent with a shift toward more severe outcomes on higher-speed night corridors.

Intersection status and precise crash location show notable contrasts across lighting. With junction related coded as (0 = non-junction; 1 = intersection-related), severe outcomes are lower at intersections in both time regimes but diverge sharply at night: by Day, severe shares are 26.9% (non-junction) vs. 17.7% (intersection-related); at Night they climb to 43.8% (non-junction) vs. 29.9% (intersection-related). The location on the road which somehow overlap the junction/non-junction part coded as (0 = along travel way; 1 = intersection/other parts) aligns with this pattern: along-way crashes are both more common and more severe at Night (share of Night crashes along-way 55.8%; severe 45.5%) than by Day (share 41.8%; severe 28.6%). Distributionally, night crashes are less likely to be intersection-related (37.5% Night vs. 48.7% Day), further concentrating nighttime harm in midblock contexts where operating speeds and crossing distances are typically greater and control is limited. Street lighting mitigates—but does not erase—nighttime risk. Using street light indicator, severe outcomes remain lower where lights exist in both regimes: by Day, severe is 33.9% (no lights) vs. 21.6% (lights), and at Night, 48.0% (no lights) vs. 37.7% (lights). Most crashes occur where lighting is present (≈93% by Day; ≈92% at Night), but the residual unlit share at Night (≈8%) is associated with the highest severe proportions. Together with the dark/light and day/night splits, these results indicate that darkness and lighting availability are central to outcome severity across contexts. With weather conditions, severe shares are slightly higher under poor weather, but the night–day gap dominates: by Day, 21.8% (clear) vs. 24.9% (bad/unclear); at Night, 38.4% (clear) vs. 39.4% (bad/unclear). Terrain (flat, rolling, and mountainous) shows modest differences by Day (≈21–29% severe, highest on mountainous), but, again, Night levels sit well above Day in every terrain class (≈31.8–40.9%). Land use is coded as 0 = rural, 1 = CBD/commercial, and 2 = residential and varies by both severity and distribution: by Day, crash shares concentrate in CBD/commercial (60.0%) and residential (34.8%), with severe ≈21–22% in those urban land uses versus ≈38% in rural. At Night, CBD/commercial (62.0%) remains the most common land-use context, and severe shares are elevated across all land uses—≈49.2% in rural and ≈38% in both CBD/commercial and residential.

Overall, dark/light and day/night differences appear against stable involvement patterns whereby average vehicles per crash hover around ~1.03 in both regimes, so the sharp contrasts in severity are not driven by materially different multi-vehicle proportions. Instead, the confluence of darkness, higher posted speeds (and thus higher operating speeds), and midblock/non-junction locations on higher-volume corridors aligns with where the dataset records the greatest concentration of deaths and the highest severe-outcome shares. This means, across Tennessee pedestrian crashes, darkness and nighttime conditions consistently align with higher fatal and serious-injury proportions; these effects intensify on faster corridors, at non-junction locations, and where street lighting is absent, while persisting—albeit at lower levels—even where lighting is present.

4.2. Tests of Variables Influencing Pedestrian Crashes

In addition to model-based analyses, non-parametric and inferential statistical tests were conducted to evaluate whether pedestrian fatalities or injuries and their attributes varied significantly across roadway segments characterized by time of the day (day vs. night), different posted speed limits, features and other conditions,

Table 2. The goal of this assessment was to determine whether roadway night/day environment—and by other factors in extension has a measurable effect on the occurrence of pedestrian crashes. The test evaluated the null hypothesis that the mean fatalities or injuries between the two groups is equal against the alternative hypothesis that a statistically significant difference exists. The formulation of the test is expressed as [

51]:

where

and

are the means of the two samples,

s1 and

s2 are the standard deviations of the two samples, and

n1 and

n2 are the sizes of the two samples. The test was conducted at a conventional 5% significance level (\alpha = 0.05) to ensure a low probability of rejecting the null hypothesis when it is true. As shown in

Table 2, the two-sample

t-tests examining pedestrian injuries and fatalities across roadway speed categories reveal a clear pattern in how posted speed limits influence pedestrian safety outcomes. For total pedestrian injuries, lower-speed corridors (15–35 mph) recorded a slightly higher mean number of injuries per crash (mean = 0.94) compared to higher-speed corridors (40–45 mph; mean = 0.89), and the difference (t = 7.30,

p < 0.001) is statistically significant. This suggests that crashes in lower-speed, pedestrian-dense environments tend to produce more injury cases, reflecting higher pedestrian activity and exposure. However, when considering total pedestrians killed, the pattern reverses markedly. Higher-speed roadways show a substantially greater mean fatality rate (mean = 0.117) than lower-speed roads (mean = 0.051), with a highly significant difference (t = −16.11,

p < 0.001). These findings underscore the critical influence of roadway speed environment whereby lower speeds are associated with more pedestrian injuries, and higher speeds dramatically elevate fatality risk.

4.3. Box Plots Describing Distribution of Pedestrian Injuries and Fatalities

The box plots describing the distribution of pedestrian injuries and fatalities were analyzed. The analysis of boxes showed clear patterns linking lighting and time-of-day conditions to pedestrian crash outcomes (total killed and total injured). Injury distributions were found to be higher and more dispersed under dark conditions, indicating that nighttime crashes result in more injured pedestrians. Fatalities were also found to be notably greater in dark environments, reflecting the effects of reduced visibility and higher impact severity. Similarly, nighttime crashes showed higher injury counts than daytime events, even though daytime crashes occurred more often. Areas with streetlights recorded more crashes, likely due to higher pedestrian activity, but injury variability was greater where lighting was absent—signifying higher risk per crash in poorly lit areas. Overall, box plots showed that lighting, visibility, and time of day are key determinants of pedestrian crash severity.

5. Pedestrian Crash Frequency Model Results

Table 3 shows the negative binomial regression model results that provide a statistical framework for understanding the factors influencing pedestrian crash frequencies across Tennessee’s roadway network. From a transportation-safety standpoint, several strong patterns emerge that align with established pedestrian risk dynamics. Average Annual Daily Traffic (AADT) shows a strong positive association with crash frequency, meaning that corridors with higher vehicular volumes tend to experience more pedestrian crashes. This result reflects exposure effects—larger traffic flows generate more vehicle–pedestrian conflict opportunities. Similarly, the number of lanes is positive and highly significant, reinforcing that wider facilities with more lanes expose pedestrians to longer crossing distances, multiple threat situations, and greater difficulty in assessing safe gaps. Multilane arterials, common in urban Tennessee, often combine high speeds, limited pedestrian infrastructure, and frequent driveways, contributing to elevated crash counts. Conversely, peak-hour traffic percentage exhibits a negative and highly significant relationship with pedestrian crashes. This inverse relationship suggests that pedestrian crashes are less frequent during the most congested times of day. During peak congestion, vehicle speeds are typically lower, and both drivers and pedestrians may exercise greater caution. Similarly, the negative coefficient for truck percentage indicates that segments with a higher proportion of heavy vehicles experience fewer pedestrian crashes. This can be attributed to land-use and access characteristics—truck-dominated corridors are often in industrial or limited-access areas with low pedestrian activity.

Interestingly, the posted speed environment, represented by the variable 40–45 MPH, shows a negative and significant relationship with crash frequency. This suggests that higher-speed corridors experience fewer pedestrian crashes once exposure and geometric conditions are controlled for. However, this may not be interpreted as safer conditions; rather, such facilities tend to be located in less pedestrian-oriented environments (e.g., rural arterials or controlled-access roads) with fewer pedestrians present. This finding aligns with broader safety literature that shows lower-speed urban environments experience more crashes, while higher-speed rural and suburban environments experience fewer but deadlier events [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. It is also important to note that posted speed limits do not always correspond directly to operational speeds, and the safety implications of each may vary. Operational speeds are shaped by roadway geometry, traffic density, enforcement, and driver behavior, and several studies have shown that drivers often travel above or below the posted limit depending on these contextual factors. As a result, the relationship between speed and pedestrian crash frequency and severity may be more strongly governed by actual operating speeds rather than the regulatory posted speed. While posted speed remains a practical and widely used proxy in large-scale safety analyses, future work incorporating measured operating speed distributions could provide deeper insight into how real-world speeds influence pedestrian crash outcomes.

The presence of street lighting is positively and significantly associated with crash frequency. While counterintuitive, this effect reflects the reality that street lighting is most common in urban corridors and intersections where pedestrian volumes and exposure are highest. In other words, lighting is a proxy indicator of pedestrian activity zones rather than a direct cause of crashes. The positive and significant coefficient for intersection-related crashes further supports this, as intersections represent concentrated points of pedestrian–vehicle interaction, with multiple conflict movements and variable signal timing conditions. Topographic conditions also play a role. The variable for rolling terrain shows a weak negative relationship with crash frequency, significant only at the 90% confidence level, whereas mountainous terrain exhibits a strong and highly significant negative relationship. These findings suggest that pedestrian crashes are substantially less frequent in hilly and mountainous regions, likely because such areas feature lower pedestrian densities, fewer roadway facilities with sidewalks, and less mixed land use. Flat or gently rolling terrain—characteristic of urbanized areas—supports greater pedestrian movement and, consequently, higher exposure and crash counts. The results also reveal that terrain and the land-use context significantly moderate these effects—flatter, urbanized environments amplify pedestrian exposure and crash likelihood, while mountainous and rural environments suppress them.

6. Pedestrian Crashes by Socioeconomic Spectrum

As part of this statewide pedestrian safety investigation, an Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS) approach was applied to model pedestrian crashes using both traffic-crash and sociodemographic data. The purpose of this analysis was to complement statistical models by integrating intelligent data-driven learning capable of identifying nonlinear relationships between pedestrian crash occurrences and neighborhood characteristics. The ANFIS model was developed using pedestrian crash data extracted and merged with sociodemographic variables obtained from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS) at the census block-group level. The combined dataset covered 18,565 pedestrian crash events and 4125 census block groups across Tennessee. Each block group record included information on population density, median household income, percentage of population commuting to work by private car, and percentage of housing units without vehicle ownership. Crash counts were aggregated at the block-group level to represent pedestrian exposure within five-year intervals. The integration of spatial and sociodemographic data was conducted in a Geographic Information System (GIS) environment to ensure spatial consistency between crash events and census boundaries. The ANFIS framework was designed using the Sugeno-type fuzzy inference model with four input variables and one output (number of pedestrian crashes). The system adopted Gaussian membership functions for each input and a linear output membership function. Model training was conducted using the hybrid optimization method, which combines the least-squares estimator with back-propagation learning to iteratively minimize error between predicted and observed values. The model’s performance was evaluated through the Root Mean Square Error (

RMSE) between observed and predicted crash counts during training epochs.

where

n: the number of samples;

Yobs,i: the observed output value for the ith sample;

Ymodel,i: the predicted output value by FIS model for the ith sample.

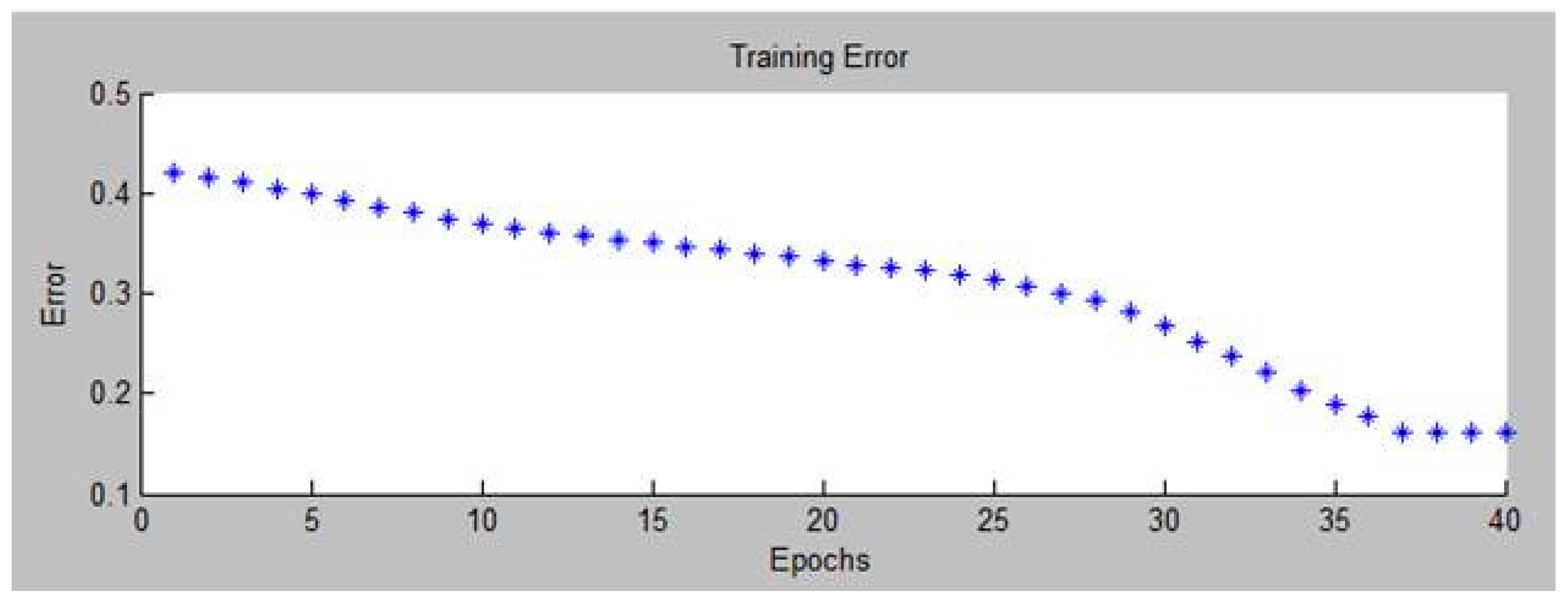

The optimal ANFIS configuration—employing all four input variables—achieved the lowest

RMSE of 0.1607 after 37 epochs, demonstrating effective convergence and predictive accuracy,

Figure 2. Models trained with fewer inputs exhibited higher error values, confirming the importance of including the full set of sociodemographic predictors. The final fuzzy inference system contained 256 fuzzy rules, each representing a unique combination of input-variable membership values. These rules were automatically generated within the neuro-fuzzy learning process and interpreted through a rule viewer to examine how variations in input factors influence predicted crash frequencies.

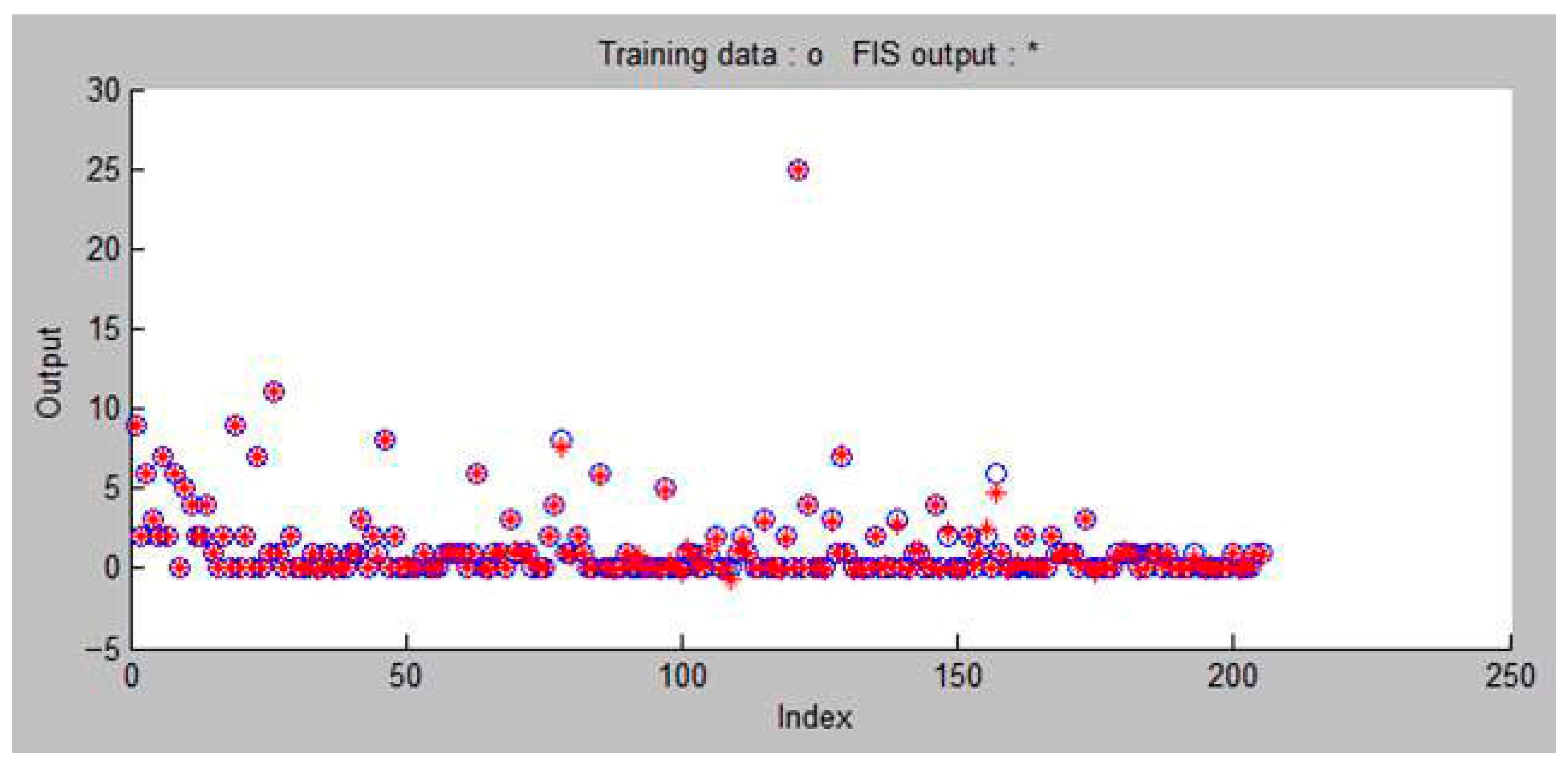

Testing of the trained model against a down-sampled set of 205 cases indicated strong predictive capability, as the simulated FIS outputs closely matched observed crash data,

Figure 3. Many block groups displayed low crash counts, consistent with over-dispersed pedestrian crash distributions observed in previous studies. The inference process revealed clear associations among key sociodemographic characteristics. The model indicated that higher pedestrian crash frequencies are strongly linked to greater population density, suggesting that areas with concentrated pedestrian activity—such as urban centers, retail corridors, and recreational zones—face elevated exposure risks. Conversely, higher proportions of residents commuting by private car corresponded with lower crash counts, reflecting reduced pedestrian exposure. The analysis also identified a strong positive relationship between the proportion of households with no vehicle ownership and pedestrian crash frequency. Households lacking access to private vehicles rely more heavily on walking, thereby increasing exposure to traffic conflicts. Median household income showed a comparatively weaker direct effect, although lower-income neighborhoods generally exhibited slightly higher crash frequencies, possibly reflecting differences in mobility behavior and pedestrian infrastructure availability. The developed ANFIS model successfully captured complex nonlinear interactions between neighborhood-level characteristics and pedestrian crash frequencies. The low

RMSE and well-fitted prediction curves underscore the method’s ability to replicate observed data trends effectively. The fuzzy-rule base provides interpretable relationships that assist transportation planners in understanding how combinations of population, income, and travel-behavior attributes shape pedestrian crash risk across communities. From a planning perspective, this neuro-fuzzy framework demonstrates potential as a decision-support tool for identifying high-risk neighborhoods based on sociodemographic profiles. The model’s outputs inform prioritization of pedestrian safety interventions in densely populated, low-income areas with limited vehicle ownership. The ANFIS-based analysis of pedestrian crashes confirms that sociodemographic factors exert significant influence on crash distribution across Tennessee. Areas characterized by higher pedestrian exposure, denser population, and low vehicle ownership are consistently associated with elevated crash risk. The predictive performance of the developed model—supported by a minimal training error and stable convergence—validates the applicability of ANFIS for pedestrian safety modeling.

7. Machine Learning Analysis

Apart from the above analytical approaches applied in previous sections—including descriptive statistics, non-parametric testing, crash frequency modeling using the negative binomial method, and visualization through box and violin plots—the study also evaluated pedestrian safety through machine learning techniques to further assess the influence and relative importance of contributing variables. Gradient-boosting algorithms, specifically XGBoost and LightGBM, were applied to identify key predictors and quantify their contribution to pedestrian crash frequency. These models were not used for comparative performance purposes but rather as complementary analytical tools to enhance understanding of the factors shaping pedestrian crash occurrences. Alongside the Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS) used to analyze socioeconomic influences, the integration of machine learning and statistical modeling provided a comprehensive framework for evaluating pedestrian safety through multiple, data-driven perspectives. The XGBoost model showed the better result compared to all other model evaluated as its prediction was more accurate without adding more tuning hyperparameter. XGBoost model is supervised machine learning algorithm based on gradient boosting in which it builds the strong and accurate model by assembling the decision trees for taking the weak trees which each tree tried to correct error by itself from previous errors and at the end they combine (boosting) to form strong and accurate prediction. Let

denote observations, where

includes roadway, environment, and other predictors (e.g., AADT, number of lanes, posted speed, land use, etc.), and

is the pedestrian crash frequency. XGBoost then models the prediction as an additive ensemble of decision trees as follows.

where each

fk is a regression tree mapping features to a leaf weight. At iteration

t, XGBoost adds a new tree

ft to minimize a regularized objective:

where

l is the squared error loss for regression (consistent with your MSE criterion). XGBoost then uses a second-order Taylor expansion of the loss around current predictions

where the first and second derivatives (gradient and Hessian) under squared error are

Dropping constants, the stagewise objective becomes

After fitting, XGBoost applies shrinkage (“learning rate”) to temper each step:

where

η = 0.05 for this paper configuration and 300 trees which improves generalization by preventing large, abrupt updates.

As illustrated in Equations (5)–(9), the XGBoost regression model was executed as an ensemble of 300 trees (maximum depth = 6) trained using a learning rate of 0.05. Model optimization was conducted using 5-fold cross-validation to minimize mean-squared error. The tuned model had a squared R of 0.857, indicating that 85.7 % of the pedestrian crash frequency variability was explained by the independent variables such as AADT, number of lanes, etc. The model detected nonlinear relationships among traffic exposure (AADT), roadway geometry, and operation variables without overfitting through subsampling and feature-column sampling.

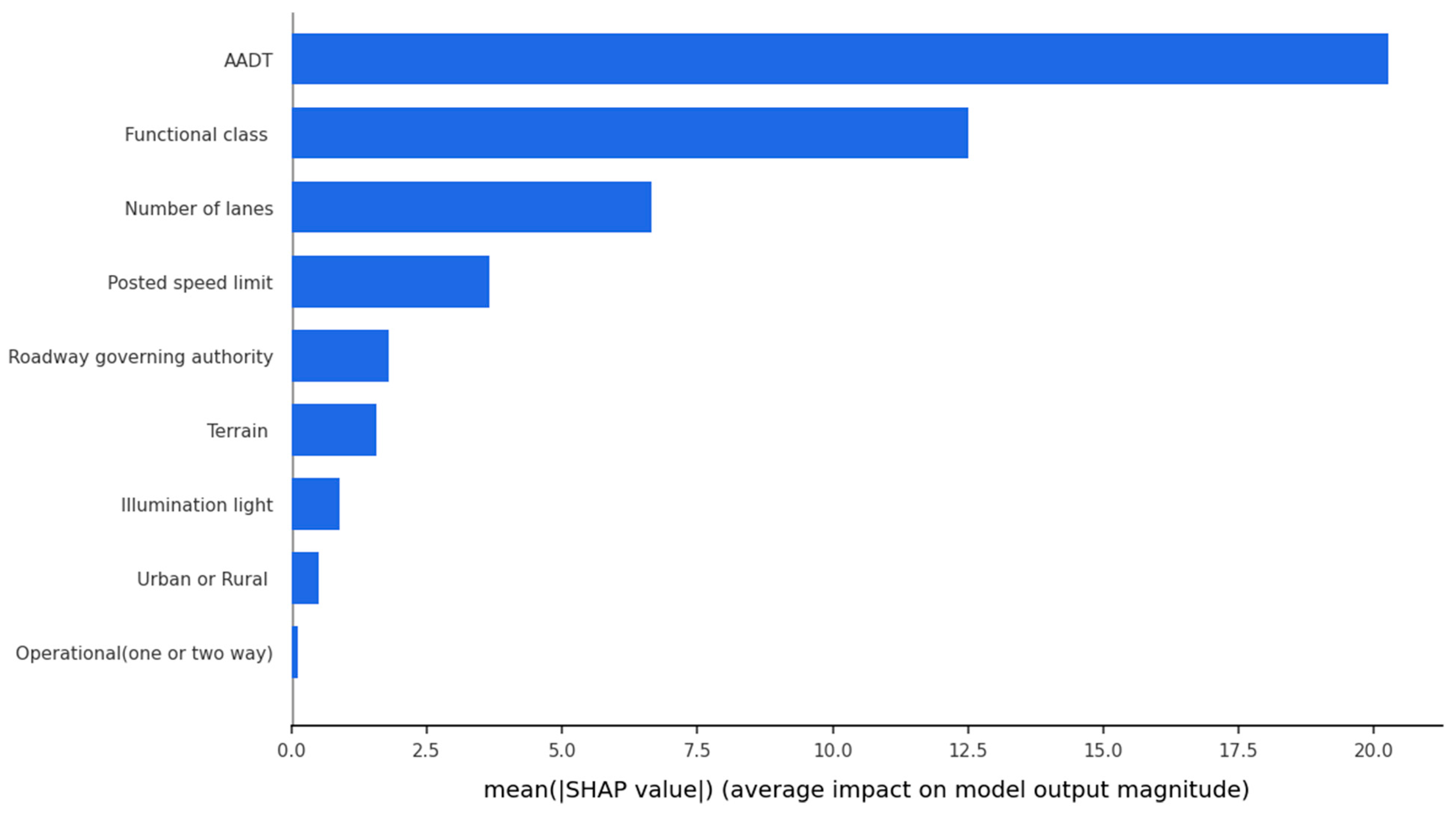

Figure 4 illustrates the contribution of all variables in pedestrian crashes, and its key features seem to be more contributors in pedestrian crash frequency.

Figure 5 presents the SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) summary results for the XGBoost pedestrian crash frequency model, illustrating the relative importance of each variable in predicting the number of pedestrian crashes. SHAP values quantify each feature’s average contribution to the model’s output, meaning variables with higher mean SHAP values have a greater overall impact on predicted crash frequency.

Figure 4 model results show that AADT (Average Annual Daily Traffic) is by far the most influential factor affecting pedestrian crash frequency. This strong effect reflects the fundamental exposure relationship—segments with higher traffic volumes inherently present more opportunities for vehicle–pedestrian interactions, thereby increasing the likelihood of pedestrian crashes. Functional class ranks second, indicating that roadway hierarchy (e.g., local streets, collectors, arterials) significantly shapes crash occurrences. Higher-class facilities like urban arterials, which carry higher volumes and speeds, typically exhibit greater pedestrian crash potential due to higher conflict densities and limited pedestrian infrastructure. The number of lanes is the third most influential factor, underscoring the geometric risk associated with wider cross-sections. Multi-lane roads increase pedestrian exposure time, the number of potential conflict points, and the complexity of crossing decisions, all of which contribute to elevated crash frequencies. The posted speed limit follows, showing that crash occurrence is also sensitive to operating speeds; higher speed environments both increase stopping distances and reduce driver reaction windows, amplifying crash likelihood even if exposure levels are held constant. Other contextual factors—such as roadway governing authority, terrain, and illumination/light conditions—show moderate but meaningful effects. Terrain likely reflects regional and environmental variations, where flatter urban areas experience more pedestrian activity and thus more crashes. The relatively smaller influence of urban or rural classification and operational characteristics (one- or two-way flow) suggests that once AADT, roadway geometry, and speed are accounted for, these broader categorical attributes contribute less unique predictive power. Technically, the XGBoost model indicates that pedestrian crash frequency is driven primarily by exposure-related and geometric variables, moderated by functional design and operating environment. The dominance of AADT and number of lanes highlights that pedestrian safety risk scales nonlinearly with traffic flow and roadway width, while secondary variables such as illumination and terrain refine predictions within those exposure contexts. Collectively, the SHAP interpretation confirms that managing pedestrian crash frequency requires strategies focused on reducing exposure, controlling speed, and improving roadway design in high-volume, multi-lane functional classes.

The analysis through SHAP force demonstrated how different roadway features influenced the model’s predicted pedestrian crash frequency for a specific roadway segment (

Figure 5). The model predicted crashes higher than the overall average prediction. The red and blue bars represent the direction and magnitude of each feature’s effect on the prediction in which the red shows the prediction is higher while the blue shows the prediction is lower. Features shown in red increased the predicted crash frequency, while those in blue decreased it. In this case, the absence of lighting, higher posted speed limit, and a greater number of lanes contributed positively to crash occurrence by increasing pedestrian crashes and risk.

8. Conclusions

This study conducted analytical assessment of pedestrian crashes across Tennessee’s roadway network, integrating statistical, computational, and intelligent modeling approaches to examine the multifaceted determinants of pedestrian safety. Using 18,565 pedestrian crash records spanning a 24-year period (2002–2025), the research combined traditional statistical tools—such as descriptive statistics, non-parametric hypothesis testing, and negative binomial regression—with advanced analytical frameworks including the Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS) and machine learning (XGBoost). This integrative approach enabled both macro- and micro-level evaluation of crash frequency, injury severity, and the underlying factors influencing pedestrian risk across varying roadway, environmental, and socioeconomic contexts. The descriptive and inferential analyses revealed that lighting and time-of-day conditions were dominant correlates of pedestrian crash severity. Crashes occurring during dark or nighttime conditions exhibited disproportionately higher fatal and serious injury shares than those in daylight, emphasizing the critical influence of visibility and illumination on pedestrian survivability. The two-sample t-tests confirmed statistically significant differences in injury and fatality rates between lower-speed (≤35 mph) and higher-speed (40–45 mph) corridors. While pedestrian crashes were more frequent in lower-speed urban environments, crashes on higher-speed corridors were far more severe, reflecting the exponential relationship between vehicle speed and fatal injury probability. Box plot visualizations demonstrated that lighting, streetlight presence, and time of day significantly shaped injury and fatality distributions, underscoring the compounded risk associated with poor illumination and higher operational speeds.

The negative binomial regression results quantified the effects of roadway and traffic variables on pedestrian crash frequencies. AADT and the number of lanes emerged as the strongest positive predictors, affirming that exposure and roadway width substantially elevate pedestrian crash likelihood. The negative relationship between peak-hour percentage and crash frequency suggests that congestion-induced lower speeds may mitigate risk. The presence of streetlights and intersection-related crashes exhibited positive associations, not as causal factors, but as proxies for high pedestrian activity zones where exposure opportunities are greatest. Conversely, rolling and mountainous terrains exhibited reduced crash frequencies, consistent with lower pedestrian densities in such areas. The ANFIS model extended the analysis by incorporating socioeconomic dimensions at the census block-group level, uncovering nonlinear interactions between demographic attributes and crash frequency. High population density and low vehicle ownership strongly correlated with increased pedestrian crashes, indicating that mobility dependence and exposure intensity are critical determinants of risk. The ANFIS model achieved high predictive accuracy (RMSE = 0.1607), demonstrating its utility in modeling complex, interdependent relationships between community characteristics and pedestrian safety outcomes. Complementing these analyses, the XGBoost machine learning model provided further insight into variable importance through SHAP interpretation. The results identified AADT, functional class, and number of lanes as the dominant predictors of pedestrian crash frequency, followed by posted speed limits and lighting conditions. These findings highlight that pedestrian crash risk is primarily governed by exposure and geometric design, moderated by operational and environmental context.

Overall, this study concludes that pedestrian safety is a multidimensional challenge influenced by roadway design, traffic exposure, illumination, speed environment, and socioeconomic context. The combined application of regression modeling, fuzzy inference, and machine learning provided a robust analytical framework capable of capturing both linear and nonlinear relationships in pedestrian crash data. The findings reinforce that mitigating pedestrian crashes require prioritizing speed management, enhancing nighttime visibility, improving roadway geometry, and addressing exposure disparities in high-density, low-income communities. Collectively, these results contribute to a deeper understanding of pedestrian safety dynamics and offer a technical foundation for data-informed policy formulation and targeted intervention planning aimed at reducing pedestrian fatalities and injuries across Tennessee’s roadway system. However, the detailed vehicle body-type information (e.g., SUVs, sedans, pickup trucks) was not available in the crash dataset, which only distinguished between passenger cars and trucks. Future studies should incorporate finer vehicle-type classifications to evaluate the elevated pedestrian injury risks associated with larger vehicles such as SUVs. Also, While this study focused on cross-sectional relationships among roadway, environmental, and socioeconomic factors, it did not explicitly account for temporal autocorrelation across the 24-year dataset; future research should incorporate longitudinal or spatial-temporal modeling to capture year-to-year dependencies in pedestrian crash patterns.