A Biomechanical Analysis of Posture and Effort During Computer Activities: The Role of Furniture

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Justification

1.2. Previous Furniture Research

1.3. Previous Musculoskeletal Disorders Research

1.4. Previous Research on Techniques

1.5. The Present Study

2. Methodology

2.1. Participants

2.2. Tests

- P1. High Desk Position (PA1), relative to P0, the chair is adjusted so that the elbows are 10 cm below the desk.

- P2. No Arm Support (PA2), relative to P0, with the screen in reference T0, the workspace on the desk is limited to simulate a 50 cm space, such that there is not enough room to rest the wrists or forearms. The keyboard is moved to the edge of the desk, and the armrests are lowered to prevent their use.

- P3. Laptop Position (PA3), relative to P0, the desktop computer is replaced by the laptop, adjusting the workspace to the user’s preference, while ensuring at least 10 cm of space between the edge of the desk and the edge of the laptop.

- P4. High Desk Position (PA1) with no arm support (PA2), relative to P0, the chair is lowered so that the elbows are 10 cm below the desk (the desk height is adjusted if necessary), in addition to the configurations described in PA1 and PA2.

- P5. High Desk Position (PA1) with laptop (PA3), relative to P0, the chair is lowered so that the elbows are 10 cm below the desk (the desk height is adjusted if necessary), in addition to the configurations described in PA1 and PA3.

- P6. No Arm Support (PA2) with laptop (PA3), relative to P0, the configurations described in PA2 and PA3 are applied.

- P7. High Desk Position (PA1) with an arm support (PA2) and Laptop (PA3), relative to P0, the chair is lowered so that the elbows are 10 cm below the desk (the desk height is adjusted if necessary), in addition to the configurations described in PA1, PA2, and PA3.

3. Experimental Design

3.1. Posture Analysis

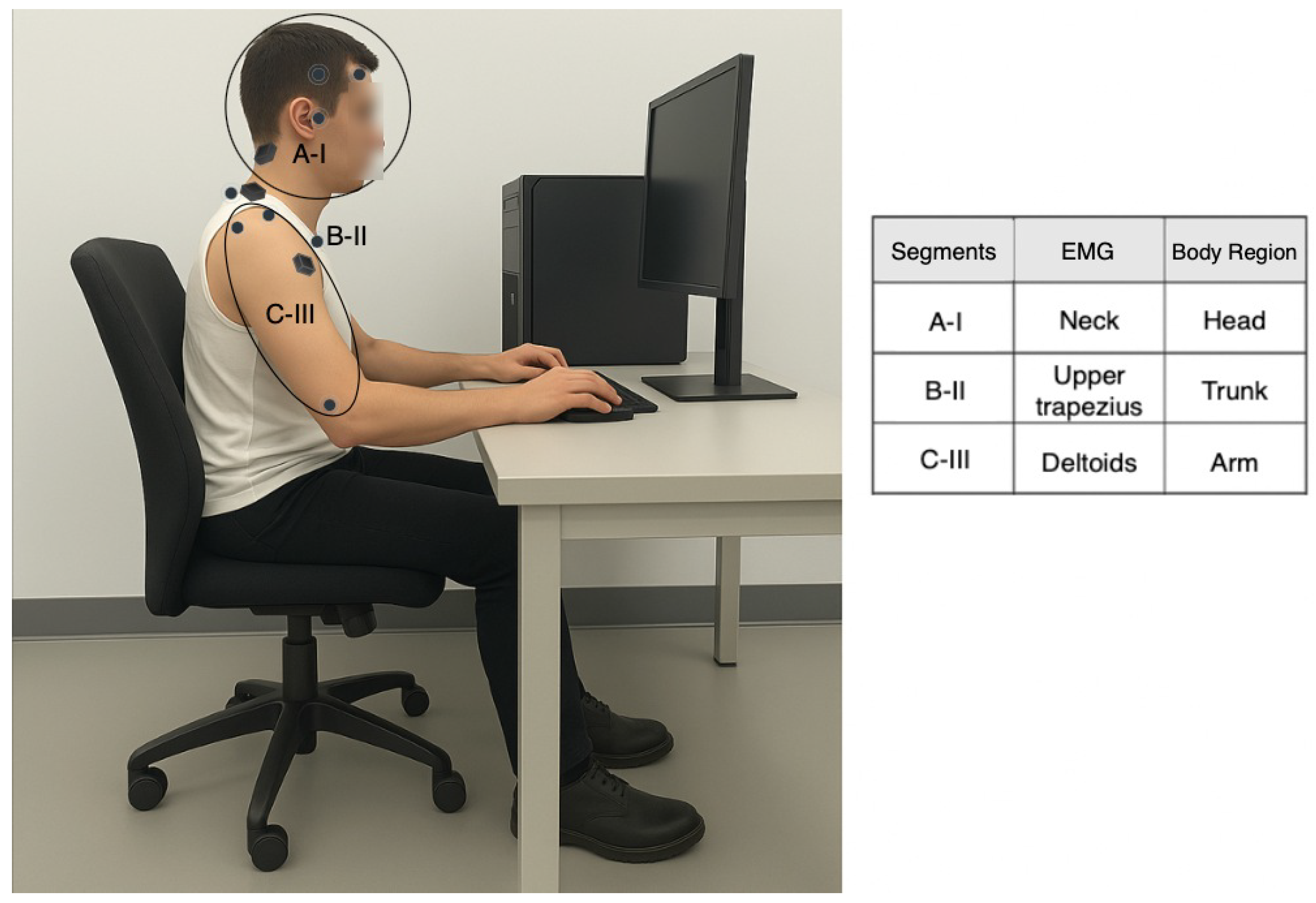

3.2. Stress Analysis

3.3. Data Processing

Statistical Assumptions

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis of Posture and Efforts

4.2. Anatomical Postures (Head, Trunk and Arm) for Furniture Purposes (High Table, Chair Without Armrests and Laptop)

4.3. Anatomical Stresses (Neck, Upper Trapezius, and Deltoid) Due to Furniture (High Table, Chair Without Armrests, and Laptop)

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MSD | Musculoskeletal Disorder |

| RPE | Perceived exertion rate |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| MVC | Maximum voluntary contraction |

| TMJ | Temporomandibular joint |

| EMG | Electromyographic |

| APDF | Amplitude probability distribution function |

| RMS | Root mean square |

| RSI | Repetitive strain injuries |

| sEMG | Surface electromyography |

References

- Romeo, M.; Yepes-Baldó, M.; Soria, M.Á.; Jayme, M. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on higher education: Characterizing the psychosocial context of the positive and negative affective states using classification and regression trees. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 714397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingel, J.; Neiman, B. How many Jobs can be done at home? J. Public Econ. 2020, 189, 104235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sostero, M.; Milasi, S.; Hurley, J.; Fernandez-Macías, E.; Bisello, M. Teleworkability and the COVID-19 crisis: A new digital divide? In JRC Working Papers Series on Labour, Education and Technology; Technical Report JRC121193; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Intolo, P.; Shalokhon, B.; Wongwech, G.; Wisiasut, P.; Nanthavanij, S.; Baxter, D.G. Analysis of neck and shoulder postures, and muscle activities relative to perceived pain during laptop computer use at a low-height table, sofa and bed. Work 2019, 63, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuster, R.P.; Bauer, C.M.; Gossweiler, L.; Baumgartner, D. Active sitting with backrest support: Is it feasible? Ergonomics 2018, 61, 1685–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, D.F.; Srinivasan, D.; Mathiassen, S.E.; Oliveira, A.B. Variation in upper extremity, neck and trunk postures when performing computer work at a sit-stand station. Appl. Ergon. 2019, 75, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Hu, W.; Kasal, A.; Erdil, Y.Z. The State of the Art of Biomechanics Applied in Ergonomic Furniture Design. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.S.; Huang, K.N.; Chen, H.J.; Yang, K.C. Ergonomic evaluation of new wrist rest on using computer mouse. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Advanced Materials for Science and Engineering (ICAMSE), Tainan, Taiwan, 12–13 November 2016; pp. 59–61. [Google Scholar]

- Bruno Garza, J.; Eijckelhof, B.; Johnson, P.; Raina, S.; Rynell, P.; Huysmans, M.; Van Dieën, J.; Van der Beek, A.; Blatter, B.; Dennerlein, J. Observed differences in upper extremity forces, muscle efforts, postures, velocities and accelerations across computer activities in a field study of office workers. Ergonomics 2012, 55, 670–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Garza, J.L.B.; Catalano, P.J.; Katz, J.N.; Huysmans, M.A.; Dennerlein, J.T. Developing a framework for predicting upper extremity muscle activities, postures, velocities, and accelerations during computer use: The effect of keyboard use, mouse use, and individual factors on physical exposures. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2012, 9, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellegast, R.; Hamburger, R.; Keller, K.; Krause, F.; Groenesteijn, L.; Vink, P.; Berger, H. Effects of using dynamic office chairs on posture and EMG in standardized office tasks. In Proceedings of the Ergonomics and Health Aspects of Work with Computers: International Conference, EHAWC 2007, Held as Part of HCI International 2007, Beijing, China, 22–27 July 2007; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 34–42. [Google Scholar]

- Villanueva, M.B.G.; Jonai, H.; Saito, S. Ergonomic aspects of portable personal computers with flat panel displays (PC-FPDs): Evaluation of posture, muscle activities, discomfort and performance. Ind. Health 1998, 36, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonai, H.; Villanueva, M.B.G.; Takata, A.; Sotoyama, M.; Saito, S. Effects of the liquid crystal display tilt angle of a notebook computer on posture, muscle activities and somatic complaints. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2002, 29, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, M.B.G.; Jonai, H.; Sotoyama, M.; Hisanaga, N.; Takeuchi, Y.; Saito, S. Sitting posture and neck and shoulder muscle activities at different screen height settings of the visual display terminal. Ind. Health 1997, 35, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greig, A.M.; Straker, L.M.; Briggs, A.M. Cervical erector spinae and upper trapezius muscle activity in children using different information technologies. Physiotherapy 2005, 91, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, B.R.; Her, J.G.; Lee, J.S.; Ko, T.S.; You, Y.Y. Effects of the computer desk level on the musculoskeletal discomfort of neck and upper extremities and EMG activities in patients with spinal cord injuries. Occup. Ther. Int. 2019, 2019, 3026150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Biomecánica Ocupacional, G.; Page, Á.; Molina, C.G. Guía de Recomendaciones Para el Diseño de Mobiliario ergonómico; Instituto de Biomecánica de Valencia: Valencia, Spain, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Porcar Seder, R. Aplicación del Análisis Multivariante a la Obtención de Criterios de Diseño para Mobiliario de Oficina. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat Politècnica de València, Valencia, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rohlmann, A.; Wilke, H.; Graichen, F.; Bergmann, G. Loads acting on the spine when seated on an office chair with a tilting back. Biomed. Tech. 2002, 47, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroemer, K. Cumulative trauma disorders: Their recognition and ergonomics measures to avoid them. Appl. Ergon. 1989, 20, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diebschlag, W.; Heidinger, F. Ergonomische Sitzgestaltung zur Prävention sitzhaltungsbedingter Wirbelsäulenschädigungen. Arbeitsmed. Sozialmed. Präventivmed. (ASP) 1990, 25, 123–126. [Google Scholar]

- Kamil, N.S.M.; Dawal, S.Z.M. Effect of postural angle on back muscle activities in aging female workers performing computer tasks. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2015, 27, 1967–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, T.; Iwakiri, K.; Sotoyama, M.; Tokizawa, K. Computer and furniture affecting musculoskeletal problems and work performance in work from home during COVID-19 pandemic. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2022, 64, 964–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carayon, P. Human Factors and Ergonomics in Health Care and Patient Safety. In Handbook of Human Factors and Ergonomics in Health Care and Patient Safety, 2nd ed.; Carayon, P., Ed.; CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hubaut, R.; Guichard, R.; Greenfield, J.; Blandeau, M. Validation of an embedded motion-capture and EMG setup for the analysis of musculoskeletal disorder risks during manhole cover handling. Sensors 2022, 22, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia Molina, C.V. Técnicas Instrumentales para la Evaluación del Riesgo de Lesión Musculo-Esquelética en el Puesto de Trabajo. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat Politècnica de València, Valencia, Spain, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Salvendy, G. Handbook of Human Factors and Ergonomics; John Wiley&Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, S.; Mathiassen, S.E.; Winkel, J. Normalizing upper trapezius EMG amplitude: Comparison of different procedures. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 1995, 5, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathiassen, S.; Winkel, J.; Hägg, G. Normalization of surface EMG amplitude from the upper trapezius muscle in ergonomic studies—A review. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 1995, 5, 197–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villar-Fernández, M. Posturas de Trabajo: Evaluación del Riesgo; Instituto Nacional de Seguridad e Higiene en el Trabajo: Madrid, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Village, J.; Frazer, M.; Cohen, M.; Leyland, A.; Park, I.; Yassi, A. Electromyography as a measure of peak and cumulative workload in intermediate care and its relationship to musculoskeletal injury: An exploratory ergonomic study. Appl. Ergon. 2005, 36, 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Village, J.; Trask, C. Ergonomic analysis of postural and muscular loads to diagnostic sonographers. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2007, 37, 781–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asundi, K.; Johnson, P.; Dennerlein, J. Effect of sampling strategies on variance in exposure intensity metrics of typing force and wrist postural dynamics during computer work. In Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Prevention of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders, Angers, France, 29 August–2 September 2010; Volume 29, p. 282. [Google Scholar]

- Page, A.; De Rosario, H.; Mata, V.; Hoyos, J.V.; Porcar, R. Effect of marker cluster design on the accuracy of human movement analysis using stereophotogrammetry. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2006, 44, 1113–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C. On definitions of pitches and the finite screw system for displacing a line. In Proceedings of the a Symposium Commemorating the Legacy, Works and Life of Sir Robert Stawell Ball upon the 100th Anniversary of A Treatise on the Theory of Screws, Cambridge, UK, 9–12 July 2000; University of Cambridge: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Toro, W.V. Modelado Biomecánico del Cuello Basado en la Imagen Cinemática de la Función Articular para su Aplicación en Tecnologías para la Salud y el Bienestar del ser Humano. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat Politècnica de València, València, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| ID | Code | Description |

|---|---|---|

| P0 | PER | Ergonomic scenario |

| P1 | PA1 | Table height variability |

| P2 | PA2 | Variability in use with or without chair armrests |

| P3 | PA3 | Variability in use of desktop or laptop computer |

| P4 | PA1 + PA2 | Combination of table height and chair armrest variability |

| P5 | PA1 + PA3 | Combination of table height variability and computer type |

| P6 | PA2 + PA3 | Combination of chair armrest variability and computer type |

| P7 | PA1 + PA2 + PA3 | Combination of all three factors |

| Posture (°) | Head FE | Trunk FE | Arm AR |

| P10 | −20.48 (9.59) | −5.32 (8.10) | 7.68 (10.1) |

| P50 | −15.24 (8.01) | −2.65 (7.80) | 18.56 (9.60) |

| P90 | −8.35 (7.22) | 0.49 (7.76) | 21.96 (9.37) |

| Range | 12.13 (5.72) | 5.81 (4.01) | 14.29 (4.99) |

| Effort %EMG | Neck | Upper trapezius | Deltoids |

| P10 | 23.04 (50.6) | 31.54 (23.5) | 7.69 (4.93) |

| P50 | 27.91 (52.5) | 39.68 (27.4) | 15.36 (10.5) |

| P90 | 35.02 (53.7) | 49.72 (34.8) | 26.97 (16.1) |

| Range | 11.98 (8.44) | 18.17 (18.4) | 19.27 (14.1) |

| Posture | Percentile (º) | Constant Correct Table | p | Constant Correct Chair | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head FE | P10 | −22.24 | −2.42 | *** 0.000 | 2.44 | *** 0.000 |

| P50 | −17.59 | −2.30 | *** 0.000 | 1.16 | ** 0.009 | |

| P90 | −11.23 | −2.08 | *** 0.00 | 0.24 | 0.636 | |

| Range | 11.01 | 0.34 | 0.550 | −2.20 | *** 0.000 | |

| Arm FE | P10 | 5.35 | −2.33 | ** 0.007 | 1.48 | 0.079 |

| P50 | 11.22 | −3.56 | *** 0.000 | 3.01 | ** 0.002 | |

| P90 | 16.40 | −3.00 | *** 0.005 | 1.63 | 0.115 | |

| Range | 11.05 | −0.67 | 0.299 | 0.15 | 0.813 | |

| Arm FL | P10 | −1.20 | −0.76 | 0.152 | −0.23 | 0.669 |

| P50 | 1.47 | −1.24 | * 0.017 | −0.49 | 0.338 | |

| P90 | 11.47 | −2.92 | ** 0.000 | −1.19 | * 0.034 | |

| Range | 12.67 | 2.16 | ** 0.002 | −0.97 | 0.147 | |

| Arm RA | P10 | 7.03 | 0.85 | 0.062 | 0.16 | 0.722 |

| P50 | 16.07 | −0.83 | 0.066 | 3.81 | *** 0.000 | |

| P90 | 19.27 | −0.73 | 0.131 | 0.73 | *** 0.000 | |

| Range | 12.24 | −1.58 | ** 0.000 | 3.57 | *** 0.000 |

| Posture | Percentile (°) | Table Correct | Constant | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trunk FL | P10 | 0.06 | −0.22 | 0.08 |

| P50 | 1.37 | −0.21 | 0.140 | |

| P90 | 2.86 | −0.37 | * 0.044 | |

| Range | 2.80 | −0.15 | 0.260 | |

| Trunk FE | P10 | −8.77 | 2.14 | *** 0.000 |

| P50 | −5.97 | 2.03 | *** 0.000 | |

| P90 | −1.89 | 1.30 | * 0.014 | |

| Range | 6.88 | −0.84 | * 0.012 | |

| Trunk RA | P10 | 0.45 | 0.64 | ** 0.008 |

| P50 | 2.50 | 0.69 | ** 0.009 | |

| P90 | 3.77 | 0.69 | ** 0.002 | |

| Range | 3.33 | 0.04 | 0.777 |

| Posture | Percentile (°) | Chair Correct | Constant | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P10 | −1.04 | 0.35 | 0.104 | |

| P50 | 2.12 | 0.41 | * 0.045 | |

| P90 | 5.46 | 0.19 | 0.383 | |

| Range | 6.50 | −0.16 | 0.418 | |

| Head RA | Monitor | |||

| P10 | −1.22 | 0.53 | * 0.017 | |

| P50 | 1.51 | 1.01 | *** 0.000 | |

| P90 | 4.69 | 0.96 | *** 0.000 | |

| Range | 5.91 | 0.44 | * 0.029 | |

| Head FE | P10 | −24.23 | 1.99 | *** 0.000 |

| P50 | −21.61 | 4.02 | *** 0.000 | |

| P90 | −16.63 | 5.40 | *** 0.000 | |

| Range | 7.60 | 3.41 | *** 0.000 | |

| Muscle Activity | Percentile EMG | Table Correct | Constant | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Trapezius | P10 | 31.55 | −2.81 | ** 0.004 |

| P50 | 40.75 | −6.57 | ** 0.004 | |

| P90 | 50.82 | −10.83 | ** 0.001 | |

| Range | 19.27 | −8.02 | ** 0.003 | |

| Monitor | ||||

| P10 | 8.05 | −0.14 | 0.654 | |

| P50 | 13.37 | −1.63 | 0.067 | |

| P90 | 24.65 | −2.84 | * 0.029 | |

| Range | 16.60 | −2.70 | * 0.031 | |

| Deltoids | Correct Chair | |||

| P10 | 8.00 | −0.19 | 0.518 | |

| P50 | 16.63 | 1.63 | 0.061 | |

| P90 | 31.91 | 4.42 | *** 0.001 | |

| Range | 23.92 | 4.62 | *** 0.000 | |

| Neck | P10 | 25.34 | −2.06 | 0.112 |

| P50 | 29.82 | −4.80 | * 0.012 | |

| P90 | 31.81 | −16.44 | * 0.001 | |

| Range | 6.46 | −14.38 | * 0.017 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Trujillo-Guerrero, M.F.; Venegas-Toro, W.; De la Cruz-Guevara, D.; Zambrano-Orejuela, I.; Page-Del Pozo, A.; Santos-Cuadros, S. A Biomechanical Analysis of Posture and Effort During Computer Activities: The Role of Furniture. Safety 2025, 11, 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11040122

Trujillo-Guerrero MF, Venegas-Toro W, De la Cruz-Guevara D, Zambrano-Orejuela I, Page-Del Pozo A, Santos-Cuadros S. A Biomechanical Analysis of Posture and Effort During Computer Activities: The Role of Furniture. Safety. 2025; 11(4):122. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11040122

Chicago/Turabian StyleTrujillo-Guerrero, María Fernanda, William Venegas-Toro, Danni De la Cruz-Guevara, Iván Zambrano-Orejuela, Alvaro Page-Del Pozo, and Silvia Santos-Cuadros. 2025. "A Biomechanical Analysis of Posture and Effort During Computer Activities: The Role of Furniture" Safety 11, no. 4: 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11040122

APA StyleTrujillo-Guerrero, M. F., Venegas-Toro, W., De la Cruz-Guevara, D., Zambrano-Orejuela, I., Page-Del Pozo, A., & Santos-Cuadros, S. (2025). A Biomechanical Analysis of Posture and Effort During Computer Activities: The Role of Furniture. Safety, 11(4), 122. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11040122