Platform-Driven Sustainability in E-Commerce: Consumer Behavior Toward Recycled Fashion

Abstract

1. Introduction

- offer a data-driven understanding of key behavioral consumers’ attitudes toward fashion e-commerce.

- investigate the impact of digital innovations on consumers’ decision making toward recycled retail.

- provide valuable insights into consumers’ e-commerce preferences in respect to sustainable and recycled fashion.

- understand how platform-driven innovations can boost consumers’ e-commerce preferences in respect to recycled fashion.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Quantitative Research Design

- RQ1:

- What factors influence consumers’ engagement with recycled fashion e-commerce platforms?

- RQ2:

- How do digital innovations affect consumers’ decision-making processes regarding recycled and sustainable fashion?

- RQ3:

- What preferences do consumers exhibit toward e-commerce offerings of recycled and second-hand fashion, and how do these preferences relate to their sustainability attitudes?

- RQ4:

- How can platform-driven innovations enhance consumers’ preferences to choose recycled fashion products in online retail environments?

2.2. Data Collection and Sampling Strategy

3. Results

3.1. Sample’s Socioeconomic Profile

3.2. Key Consumer Behavioral Aspects Toward Recycled Fashion E-Commerce (RQ1)

3.2.1. Frequency Statistics

3.2.2. Cluster Analysis

- The results per cluster are analyzed below:

3.3. Impact of Digital App Features on Decision-Making Toward Recycled Retail (RQ2)

3.3.1. Frequency Statistics

3.3.2. t-Test and ANOVA Results

3.4. Consumers’ E-Commerce Preferences for Sustainable and Second-Hand Fashion (RQ3)

3.4.1. Frequency Statistics

3.4.2. Chi-Square Tests

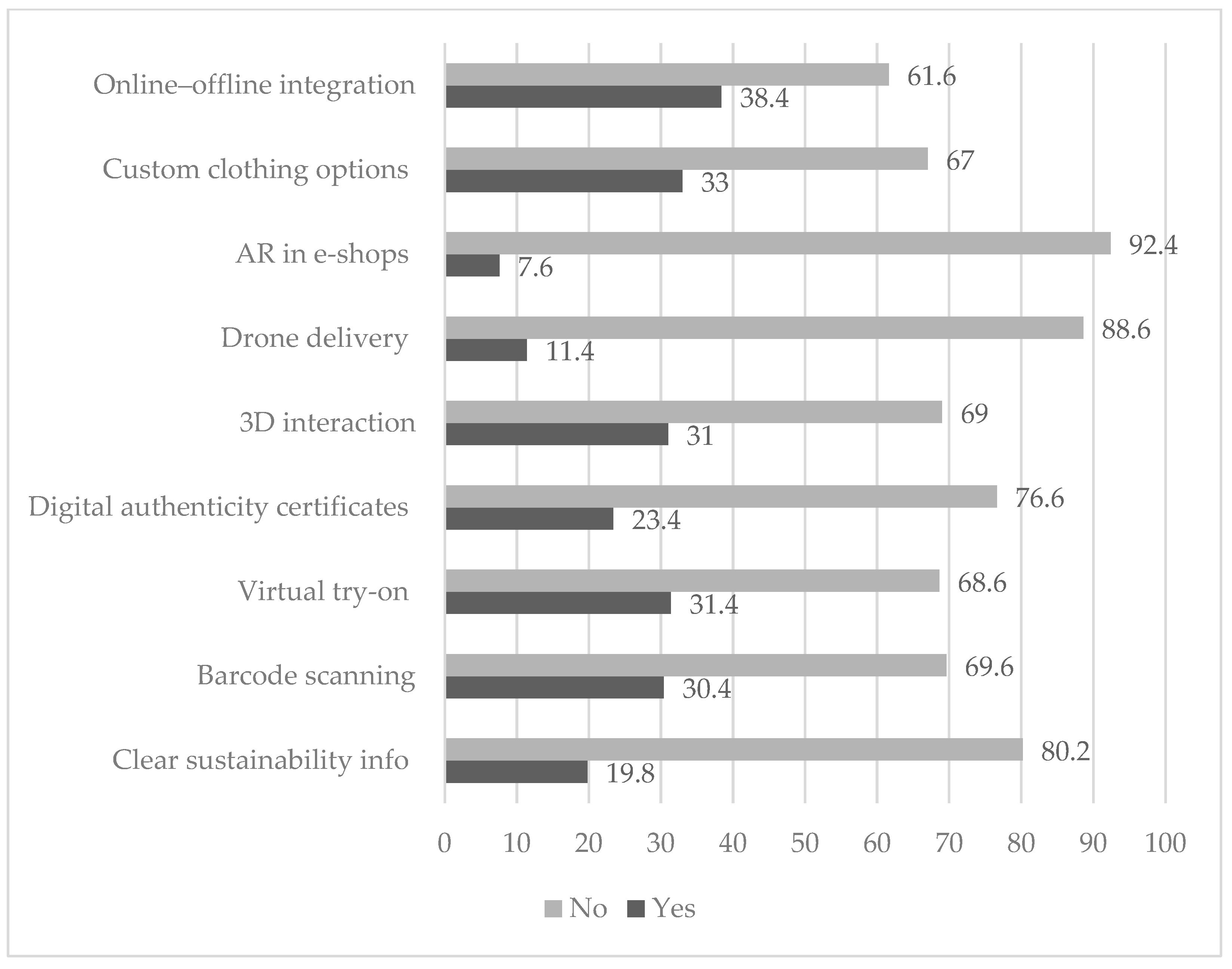

3.5. How Platform-Driven Innovations Could Boost Preferences for Recycled Fashion (RQ4)

3.5.1. Frequency Statistics

3.5.2. Factor Analysis

- Key component loadings are characterized as follows:

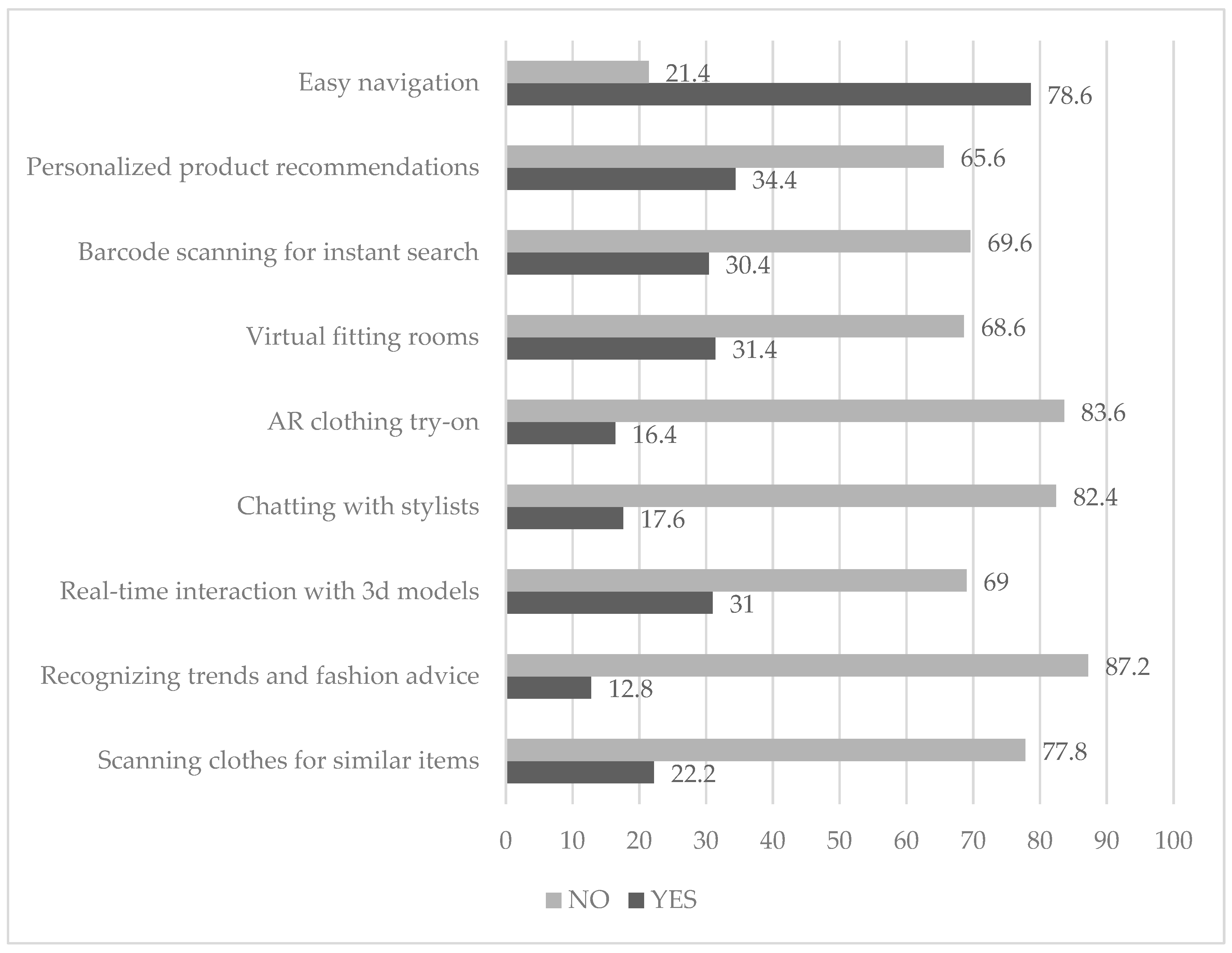

- PC1 (Usability and Personalization): Characterized by high loadings on “Virtual fitting rooms” (0.54), “AR try-on features” (0.50), and “Personalized AI recommendations” (0.43), suggesting that consumers associate these advanced features with overall app usability. The first component (Usability and Personalization) reflects how consumers link AR, virtual fitting rooms, and AI-powered suggestions with overall app ease of use. These results support that consumers share a focus on providing an efficient, tailored, and immersive shopping experience. The strong associations among them indicate that consumers view these technologically advanced tools as part of a cohesive effort to improve app usability and relevance, likely interpreting them collectively as indicators of a modern, customer-centered platform. Conceptually, it implies that adoption of or interest in one of these innovations predicts a similar attitude toward the others, forming a unified construct of perceived technological convenience and personalization.

- PC2 (Social and Interactive Features): Features strong loadings on “Chatting with stylists” (0.53), “Scanning clothes for similar items” (0.48), and “Barcode scanning” (0.43), emphasizing interactive and socially engaging elements of the app experience. The second component (Social and Interactive Features) captures a preference for features facilitating interaction and social engagement, such as chatting with stylists and scanning items. These results highlight a consumer segment motivated by enhanced engagement, feedback, and a more personalized, consultative shopping experience rather than passive browsing.

- PC3 (Trend and Knowledge Seeking): Dominated by high loadings on “Recognizing trends and fashion advice” (0.52) and negative loadings on “Barcode scanning” (−0.60), indicating a distinct dimension related to trend awareness and fashion guidance. The third component (Trend and Knowledge Seeking) highlights interest in receiving trend information and fashion advice.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

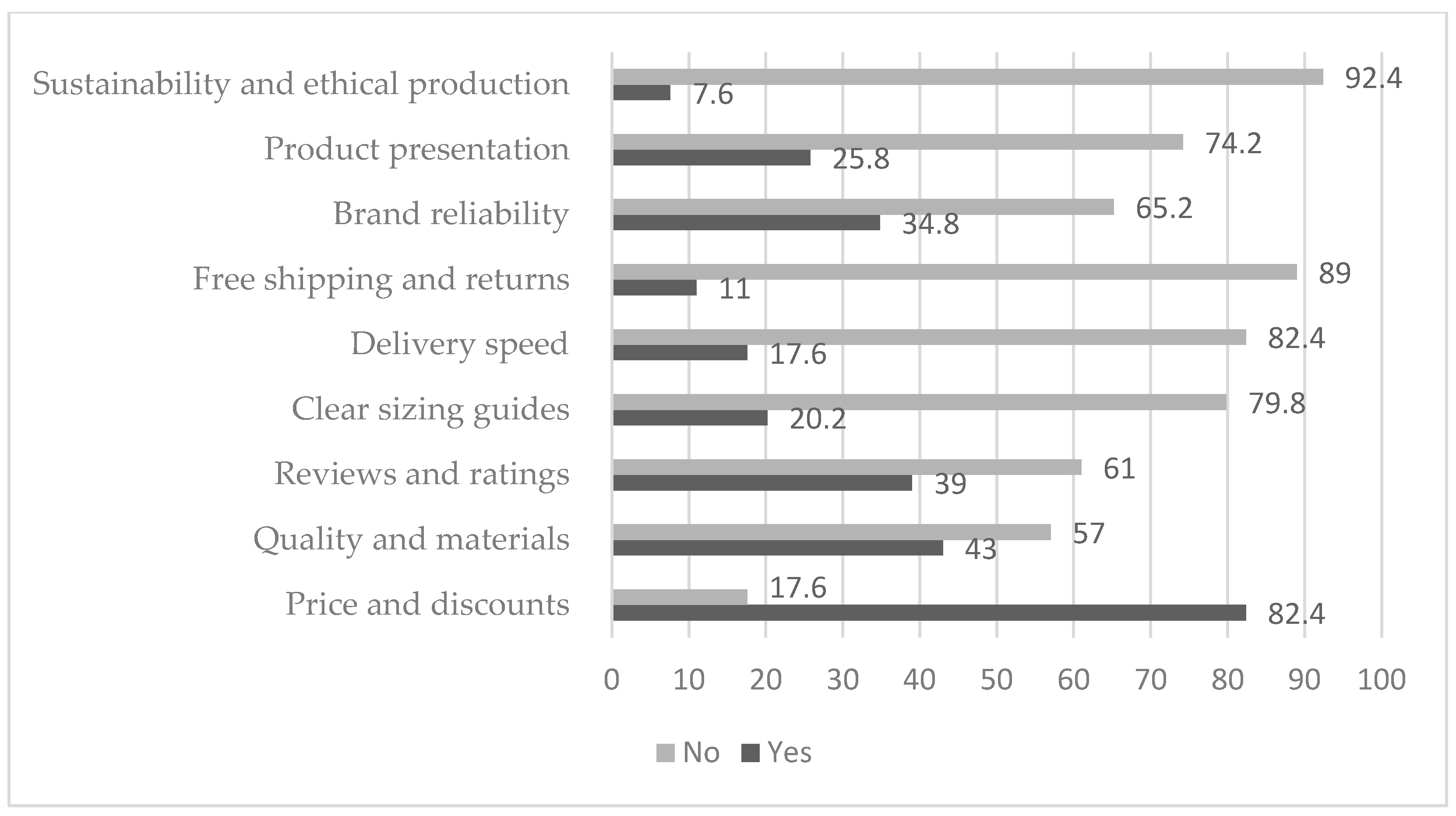

- Price and discounts remain the most influential factors for online recycled fashion shoppers.

- Only a small consumer segment demonstrates strong interest in sustainability, underscoring the gap between growing environmental awareness and actual purchasing behavior in the online recycled fashion context.

- Fashion e-commerce platforms should adopt differentiated marketing strategies that go beyond one-size-fits-all approaches to address the diverse expectations and priorities identified in the consumer clusters.

- Demographic factors, particularly education and gender, significantly shape consumer attitudes toward digital innovations in fashion e-commerce apps. Younger consumers show more openness to second-hand fashion platforms. Gender and age significantly influence consumers’ sustainable fashion behaviors and preferences, while education plays a nuanced role, primarily affecting interest in specific sustainability-related features.

- Developing engaging educational content and promoting accessible, easy-to-understand sustainability information could bridge the gap between awareness and action, fostering broader adoption of sustainable and second-hand fashion practices.

6. Policy Implications

- Introduction of financial incentives such as targeted subsidies or discount schemes for purchases of recycled garments, as well as tax benefits for retailers who prioritize circular fashion practices.

- Launch of public campaigns promoting the environmental and economic benefits of second-hand shopping to help normalize recycled fashion and reduce social stigma associated with used clothing, particularly in cultures where second-hand products may be perceived negatively.

- Establishment of clear, standardized labels indicating when a product is made from recycled materials to improve transparency and consumer confidence, empowering shoppers to make sustainable choices.

- Integration of second-hand platforms into mainstream retail environments through partnerships or digital marketplaces to increase the accessibility of recycled fashion and encourage more consumers to consider second-hand options as part of their regular shopping habits.

7. Limitations and Further Research

- Given the online sampling methodology of the research, future in-person research would strengthen the representativeness of findings across different population segments, including those with limited internet access or lower digital literacy.

- Given the country-specific sample used, conducting cross-cultural studies in various countries would expand understanding of how cultural contexts shape consumer attitudes and behaviors, ensuring the results are applicable beyond the Greek market.

- The reliance on self-reported measures offers rich, subjective insights into consumer preferences, yet incorporating observational or behavioral data in future studies would complement self-reports and provide a more comprehensive picture of actual consumer actions.

- The cross-sectional design effectively captures a snapshot of consumer opinions; however, adopting longitudinal or experimental research designs would enable the exploration of changes in attitudes over time and help identify causal relationships between digital innovations and sustainable purchasing behaviors.

- Integrating qualitative approaches such as interviews or focus groups could deepen understanding of the motivations, barriers, and social dynamics influencing engagement with recycled and second-hand fashion, further enriching quantitative results and guiding more effective policy and marketing strategies.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Section | Question | Response Scale |

|---|---|---|

| A. Demographics | What is your gender? | Male ☐ Female ☐ Other☐ |

| What is your age group? | 18–24 ☐ 25–34 ☐ 35–44 ☐ 45–54 ☐ 55+ ☐ | |

| What is your highest level of education? | High school / Vocational ☐ University Degree ☐ Master’s Degree ☐ PhD holder ☐ | |

| What is your current employment status? | Private sector ☐ Public sector ☐ Self-employed ☐ Unemployed☐ | |

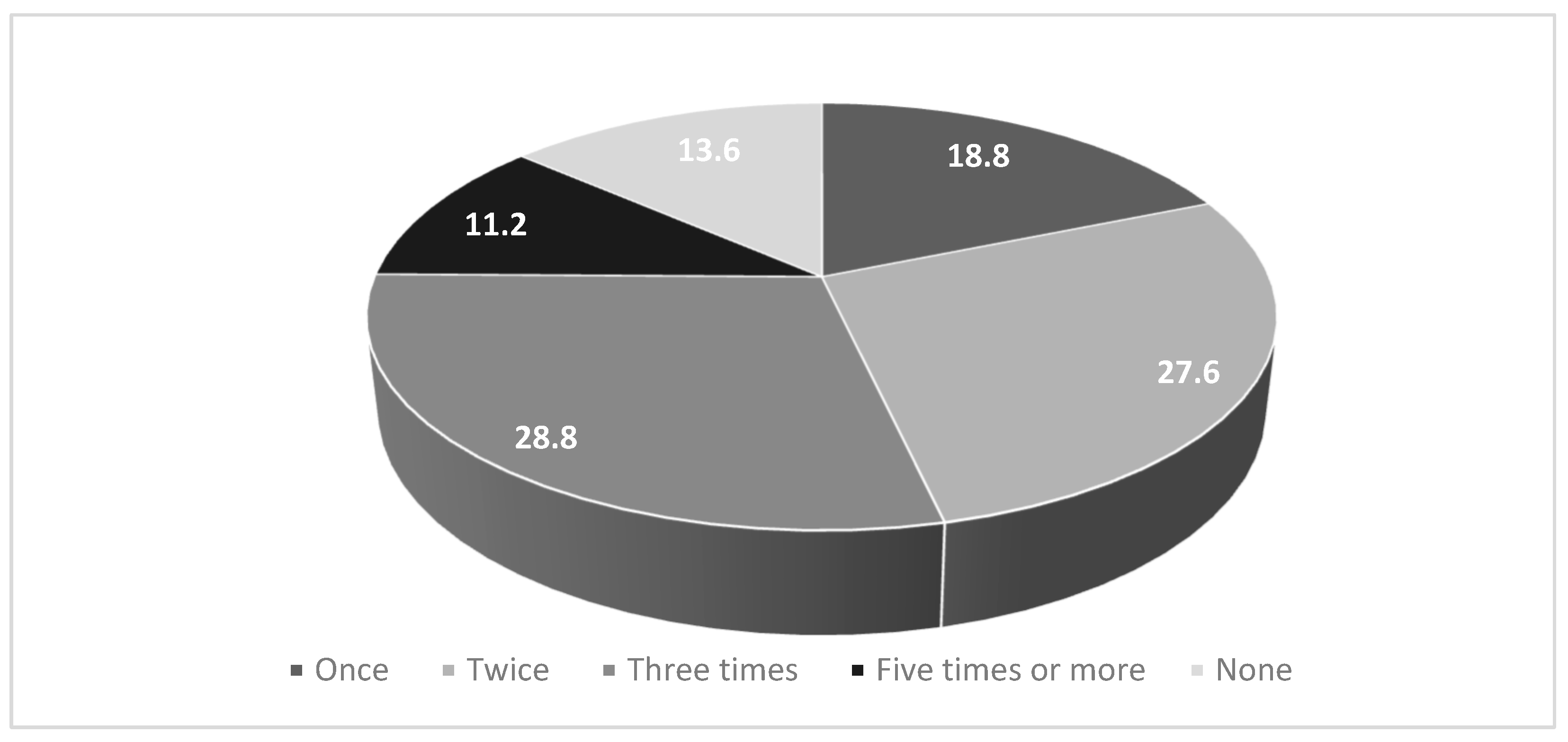

| B. Online shopping | How often do you purchase fashion items online per year? | Once ☐ Twice ☐ Three times ☐ Five times or more ☐ none ☐ |

| Which platforms do you use most frequently to purchase fashion items? (Multiple selection possible) | Official brand websites ☐ Amazon/Zalando ☐ Social media shops ☐ Second-hand platforms ☐ | |

| Which fashion apps do you use? (Select all that apply) | SHEIN ☐ ASOS ☐ Zalando ☐ Other ☐ None ☐ | |

| Which of the following factors influence your decision to purchase recycled fashion items from online stores? (Select all that apply) | Price and discounts ☐ Quality and materials ☐ Reviews and ratings ☐ Clear sizing guides ☐ Delivery speed ☐ Free shipping and returns ☐ Brand reliability ☐ Product presentation (images, etc.) ☐ Sustainability and ethical production ☐ | |

| What are your biggest concerns when shopping recycled clothing online? (Select all that apply) | Inability to try on clothes ☐ Fit or quality issues ☐ High shipping costs ☐ Delayed delivery ☐ Returns complexity/cost ☐ Store reliability ☐ Payment/data security ☐ Wrong or defective orders ☐ | |

| C. Impact of Digital App Features | Which of the following app features do you find useful for buying recycled fashion items? (Select all that apply) | Easy navigation ☐ Personalized AI recommendations ☐ Barcode scanning for similar items ☐ Virtual fitting room ☐ Augmented reality (AR) try-on ☐ Chat with stylists ☐ Real-time 3D interaction ☐ Trend recognition and fashion advice ☐ Scanning clothes to find similar products ☐ |

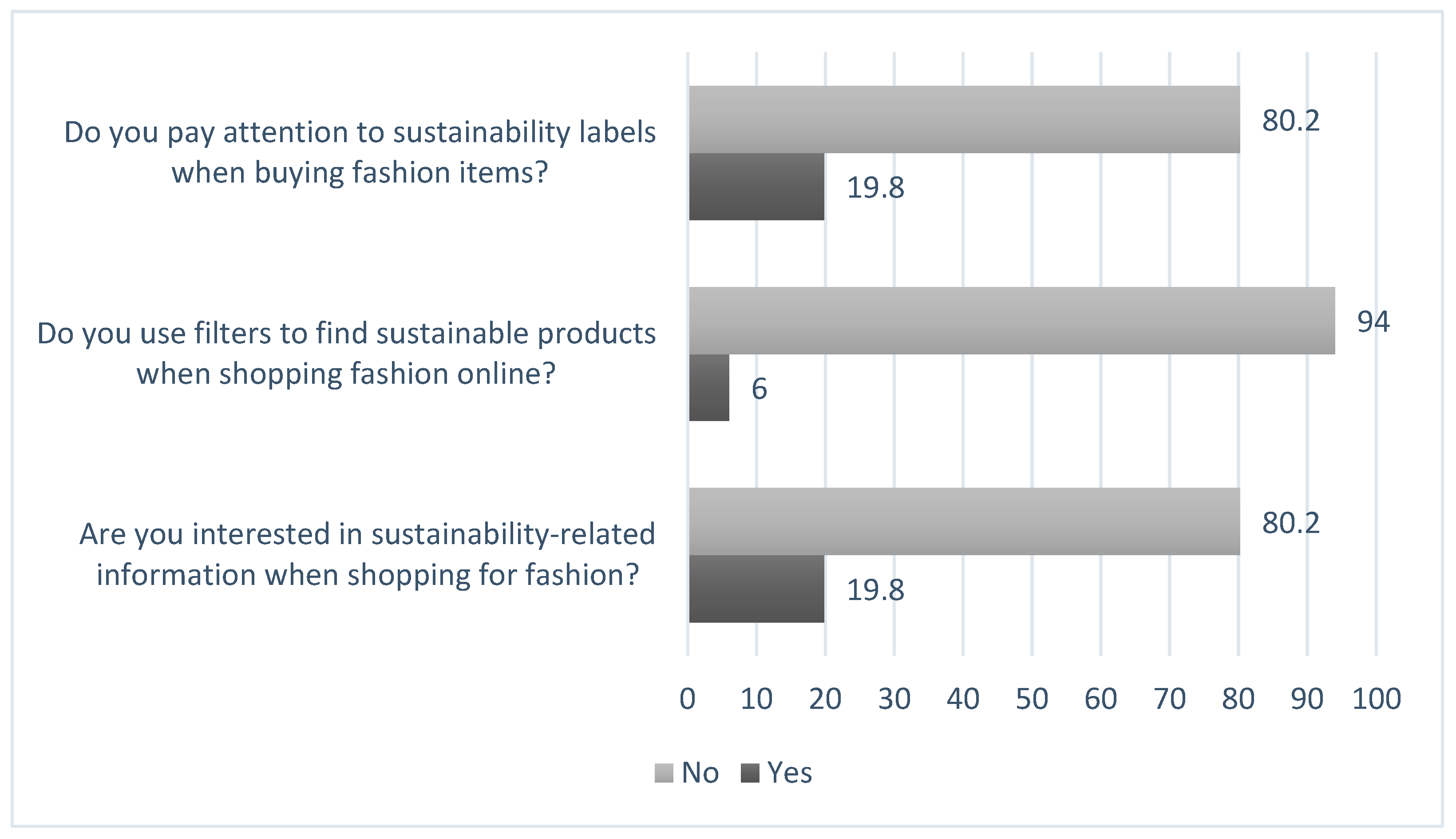

| D. Sustainability Preferences | Does sustainability influence your fashion purchases? | Yes ☐ No☐ |

| Do you use second-hand platforms to purchase fashion items like (Vinted or Depop)? | Yes ☐ No☐ | |

| Are you interested in sustainability-related information when shopping for fashion? | Yes ☐ No☐ | |

| Do you use filters to find sustainable products when shopping fashion online? | Yes ☐ No☐ | |

| Do you pay attention to sustainability labels when buying fashion items? | Yes ☐ No☐ | |

| E. Digital marketing Innovations | Which of the following innovations would motive you to purchase recycled or sustainable fashion? (Select all that apply) | Clear sustainability info ☐ Barcode scanning ☐ Virtual try-on ☐ Digital authenticity certificates ☐ 3D interaction ☐ Drone delivery ☐ AR in e-shops ☐ Custom clothing options ☐ Online–offline integration ☐ |

References

- McKinsey & Company. The State of Fashion 2025: Challenges at Every Turn; McKinsey & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Centobelli, P.; Abbate, S.; Nadeem, S.P.; Garza-Reyes, J.A. Slowing the Fast Fashion Industry: An All-Round Perspective. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2022, 38, 100684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niinimäki, K.; Peters, G.; Dahlbo, H.; Perry, P.; Rissanen, T.; Gwilt, A. The Environmental Price of Fast Fashion. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Fashion Agenda and Boston Consulting Group. Pulse of the Fashion Industry 2019; Global Fashion Agenda: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2019; Available online: https://globalfashionagenda.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Pulse-of-the-Fashion-Industry2019.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Abbate, S.; Centobelli, P.; Cerchione, R.; Nadeem, S.P.; Riccio, E. Sustainability Trends and Gaps in the Textile, Apparel and Fashion Industries. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 26, 2837–2864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-López, A.; Iglesias, V.; Puente, J. Slow Fashion Trends: Are Consumers Willing to Change Their Shopping Behavior to Become More Sustainable? Sustainability 2021, 13, 13858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandual, A.; Pradhan, S. Fashion Brands and Consumers Approach Towards Sustainable Fashion. In Fast Fashion, Fashion Brands and Sustainable Consumption; Muthu, S.S., Ed.; Textile Science and Clothing Technology; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 37–54. ISBN 9789811312670. [Google Scholar]

- McQueen, R.H.; McNeill, L.S.; Huang, Q.; Potdar, B. Unpicking the Gender Gap: Examining Socio-Demographic Factors and Repair Resources in Clothing Repair Practice. Recycling 2022, 7, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durant, D.; Lucas, A. Manufacturing a Better Planet: Challenges Arising from the Gap between the Best Intentions and Social Realities. Recycling 2018, 3, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casciani, D.; Chkanikova, O.; Pal, R. Exploring the Nature of Digital Transformation in the Fashion Industry: Opportunities for Supply Chains, Business Models, and Sustainability-Oriented Innovations. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2022, 18, 773–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guercini, S.; Bernal, P.M.; Prentice, C. New Marketing in Fashion E-Commerce. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2018, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikram, M. Transition toward Green Economy: Technological Innovation’s Role in the Fashion Industry. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2022, 37, 100657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, N. The Role of Technology in Sustainable Fashion. In Threaded Harmony: A Sustainable Approach to Fashion; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2024; pp. 97–107. ISBN 978-1-83608-153-1. [Google Scholar]

- Murugesan, B.; Jayanthi, K.B.; Karthikeyan, G. Integrating Digital Twins and 3D Technologies in Fashion: Advancing Sustainability and Consumer Engagement. In Illustrating Digital Innovations Towards Intelligent Fashion; Raj, P., Rocha, A., Dutta, P.K., Fiorini, M., Prakash, C., Eds.; Information Systems Engineering and Management; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 18, pp. 1–88. ISBN 978-3-031-71051-3. [Google Scholar]

- Testa, D.S.; Bakhshian, S.; Eike, R. Engaging Consumers with Sustainable Fashion on Instagram. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2021, 25, 569–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.P.; Sharief, S.; Rani, S. Digital Fashion and Social Media Influencer in Industry 5.0. In Illustrating Digital Innovations Towards Intelligent Fashion; Raj, P., Rocha, A., Dutta, P.K., Fiorini, M., Prakash, C., Eds.; Information Systems Engineering and Management; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 18, pp. 125–147. ISBN 978-3-031-71051-3. [Google Scholar]

- Sayem, A.S.M. Digital Fashion Innovations for the Real World and Metaverse. Int. J. Fash. Des. Technol. Educ. 2022, 15, 139–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumarliah, E.; Usmanova, K.; Mousa, K.; Indriya, I. E-Commerce in the Fashion Business: The Roles of the COVID-19 Situational Factors, Hedonic and Utilitarian Motives on Consumers’ Intention to Purchase Online. Int. J. Fash. Des. Technol. Educ. 2022, 15, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardabkhadze, I.; Bereznenko, S.; Kyselova, K.; Bilotska, L.; Vodzinska, O. Fashion Industry: Exploring the Stages of Digitalization, Innovative Potential and Prospects of Transformation into an Environmentally Sustainable Ecosystem. East.-Eur. J. Enterp. Technol. 2023, 1, 86–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassalo, A.L.; Marques, C.G.; Simões, J.T.; Fernandes, M.M.; Domingos, S. Sustainability in the Fashion Industry in Relation to Consumption in a Digital Age. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juge, E.; Pomiès, A.; Collin-Lachaud, I. Digital Platforms and Speed-Based Competition: The Case of Secondhand Clothing. Rech. Appl. Mark. (Engl. Ed.) 2022, 37, 36–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, Y.; Choi, J.; Gantumur, M.; Kim, N. Technology-Based Strategies for Online Secondhand Platforms Promoting Sustainable Retailing. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strähle, J.; Klatt, L.M. The Second Hand Market for Fashion Products. In Green Fashion Retail; Strähle, J., Ed.; Springer Series in Fashion Business; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 119–134. ISBN 978-981-10-2439-9. [Google Scholar]

- Le Zotte, J. The Cultural Economies of Secondhand Clothes. In The Routledge History of Fashion and Dress, 1800 to the Present; Routledge: London, UK, 2023; pp. 507–524. ISBN 978-0-429-29560-7. [Google Scholar]

- Turunen, L.L.M.; Leipämaa-Leskinen, H.; Sihvonen, J. Restructuring Secondhand Fashion from the Consumption Perspective. In Vintage Luxury Fashion; Ryding, D., Henninger, C.E., Blazquez Cano, M., Eds.; Palgrave Advances in Luxury; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 11–27. ISBN 978-3-319-71984-9. [Google Scholar]

- Schiaroli, V.; Dangelico, R.M.; Fraccascia, L. Mapping Sustainable Options in the Fashion Industry: A Systematic Literature Review and a Future Research Agenda. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 33, 431–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Jung, H.J.; Lee, Y. Consumers’ Value and Risk Perceptions of Circular Fashion: Comparison between Secondhand, Upcycled, and Recycled Clothing. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Fernandez, A.; Aramendia-Muneta, M.E.; Alzate, M. Consumers’ Awareness and Attitudes in Circular Fashion. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2023, 11, 100144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, P.H. Enabling Circular Business Models in the Fashion Industry: The Role of Digital Innovation. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2022, 71, 870–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Saleem, M.F.; Soomro, Y.A. Circular Fashion: Values, Risks, and Its Effects on Purchasing Habits of Consumers. J. Mark. Strateg. 2023, 5, 302–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Itria, E.; Aus, R. Circular Fashion: Evolving Practices in a Changing Industry. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2023, 19, 2220592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidu, R.K.; Eghan, B.; Acquaye, R. A Review of Circular Fashion and Bio-Based Materials in the Fashion Industry. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2024, 4, 693–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaheer Mukthar, K.P.; Nagadeepa, C.; Selvaratnam, D.P.; Pushpa, A.; Shukla, N. Sustainable Wardrobe: Recycled Clothing towards Sustainability and Eco-Friendliness. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.; Patel, P. Redefining Fashion Sustainability for Industry 5.0: Sustainability. In Advances in Business Strategy and Competitive Advantage; Neu, R., Qian, X., Yu, P., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 139–166. ISBN 9798369343388. [Google Scholar]

- Harmsen, P.; Scheffer, M.; Bos, H. Textiles for Circular Fashion: The Logic behind Recycling Options. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.M.; Heinzel, T. Human Perceptions of Recycled Textiles and Circular Fashion: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peleg Mizrachi, M.; Tal, A. Sustainable Fashion—Rationale and Policies. Encyclopedia 2022, 2, 1154–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, H. SLOW + FASHION—An Oxymoron—Or a Promise for the Future …? Fash. Theory 2008, 12, 427–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Woodhead, A. Making Wardrobe Space: The Sustainable Potential of Minimalist-inspired Fashion Challenges. Area 2023, 55, 274–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardey, A.; Booth, M.; Heger, G.; Larsson, J. Finding Yourself in Your Wardrobe: An Exploratory Study of Lived Experiences with a Capsule Wardrobe. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2022, 64, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, S.; Nayak, L. Marketing Sustainable Fashion: Trends and Future Directions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krejcie, R.V.; Morgan, D.W. Determining Sample Size for Research Activities. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1970, 30, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.R.; Mathur, A. The Value of Online Surveys. Internet Res. 2005, 15, 195–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etikan, I. Comparison of Convenience Sampling and Purposive Sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2016, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillman, D.A.; Smyth, J.D.; Christian, L.M. Internet, Phone, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-118-45614-9. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, K.B. Researching Internet-Based Populations: Advantages and Disadvantages of Online Survey Research, Online Questionnaire Authoring Software Packages, and Web Survey Services. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2005, 10, JCMC1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couper, M.P. Web Surveys. Public Opin. Q. 2000, 64, 464–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toker-Yildiz, K.; Trivedi, M.; Choi, J.; Chang, S.R. Social Interactions and Monetary Incentives in Driving Consumer Repeat Behavior. J. Mark. Res. 2017, 54, 364–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patwa, N.; Gupta, M.; Mittal, A. Social Proof: Empowering Social Commerce through Social Validation. Glob. Knowl. Mem. Commun. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amblee, N.; Bui, T. Harnessing the Influence of Social Proof in Online Shopping: The Effect of Electronic Word of Mouth on Sales of Digital Microproducts. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2011, 16, 91–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niinimäki, K. Eco-clothing, Consumer Identity and Ideology. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joy, A.; Sherry, J.F.; Venkatesh, A.; Wang, J.; Chan, R. Fast Fashion, Sustainability, and the Ethical Appeal of Luxury Brands. Fash. Theory 2012, 16, 273–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantano, E.; Gandini, A. Exploring the Forms of Sociality Mediated by Innovative Technologies in Retail Settings. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 77, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwood, S.; Anglim, J.; Mallawaarachchi, S.R. Problematic Smartphone Use in a Large Nationally Representative Sample: Age, Reporting Biases, and Technology Concerns. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 122, 106848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, B.; Saechang, O. Is Female a More Pro-Environmental Gender? Evidence from China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cluster | n | E-Shop Fashion | Price and Discounts | Quality and Materials | Reviews | Sizing and Fit | Delivery Speed | Free Shipping | Brand Reliability | Image and Product Presentation | Sustainability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 92 | 2.7 | 0.98 | 0.46 | 0.61 | 0 | 1 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.39 | 0 |

| 1 | 108 | 2.35 | 1 | 1 | 0.35 | 0 | 0 | 0.09 | 0.37 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 138 | 3.12 | 1 | 0.72 | 0.54 | 1 | 0.26 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 0.39 | 0 |

| 3 | 76 | 2.87 | 0.87 | 0.79 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.32 | 0.47 | 0.55 | 0.34 | 1 |

| 4 | 92 | 3.37 | 1 | 0.28 | 0.72 | 0 | 0 | 0.65 | 0.72 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 104 | 2.96 | 1 | 0.31 | 0.52 | 0.02 | 0 | 0.29 | 0.27 | 1 | 0 |

| 6 | 226 | 2.46 | 1 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.03 | 0 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 76 | 3.34 | 0 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.21 | 0.26 | 0.03 | 0.34 | 0.47 | 0 |

| 8 | 88 | 1.48 | 0 | 0.57 | 0.36 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.27 | 0.02 | 0 |

| Digital App Features | Gender (t, p) t-Test | Education (F, p) ANOVA | Age (F, p) ANOVA | Significant Demographics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Easy Navigation | t = 0.81, p = 0.416 | F = 2.78, p = 0.026 | F = 4.51, p = 0.011 | Education, Age |

| Personalized AI Recommendations | t = −1.89, p = 0.060 | F = 2.59, p = 0.036 | F = 0.21, p = 0.814 | Education |

| Barcode Scanning | t = 3.79, p < 0.001 | F = 2.84, p = 0.023 | F = 12.79, p < 0.001 | Gender, Education, Age |

| Virtual Fitting Rooms | t = −0.79, p = 0.430 | F = 7.25, p < 0.001 | F = 1.82, p = 0.162 | Education |

| AR Try-On Features | t = 1.38, p = 0.168 | F = 6.37, p < 0.001 | F = 2.18, p = 0.114 | Education |

| Chatting with Stylists | t = 2.47, p = 0.014 | F = 0.70, p = 0.593 | F = 0.62, p = 0.536 | Gender |

| Real-Time 3D Interaction | t = −0.50, p = 0.617 | F = 2.20, p = 0.067 | F = 0.56, p = 0.573 | — |

| Trends and Fashion Advice | t = 2.15, p = 0.032 | F = 0.56, p = 0.690 | F = 2.13, p = 0.119 | Gender |

| Scanning Clothes for Similar Items | t = 3.04, p = 0.002 | F = 2.53, p = 0.039 | F = 11.03, p < 0.001 | Gender, Education, Age |

| Consumer Behavior | Gender (χ2, p) | Age Group (χ2, p) | Education Level (χ2, p) | Statistically Significant Demographics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainability influences purchases | 22.30, p < 0.001 | 6.09, p = 0.048 | 0.91, p = 0.923 | Gender, Age |

| Use of second-hand platforms | 2.34, p = 0.311 | 45.70, p < 0.001 | 5.92, p = 0.205 | Age |

| Interest in sustainability information | 43.08, p < 0.001 | 3.43, p = 0.180 | 26.60, p < 0.001 | Gender, Education |

| Use of filters for sustainable products | 12.00, p = 0.002 | 4.23, p = 0.121 | 24.98, p < 0.001 | Gender, Education |

| Interest in sourcing sustainability labels | 16.90, p < 0.001 | 7.50, p = 0.024 | 7.86, p = 0.097 | Gender, Age |

| Component | Explained Variance | Cumulative Variance |

|---|---|---|

| PC1 | 0.193 | 0.193 |

| PC2 | 0.140 | 0.334 |

| PC3 | 0.128 | 0.461 |

| PC4 | 0.112 | 0.573 |

| PC5 | 0.102 | 0.675 |

| PC6 | 0.095 | 0.770 |

| PC7 | 0.089 | 0.859 |

| PC8 | 0.082 | 0.941 |

| PC9 | 0.059 | 1.000 |

| Features | PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | PC4 | PC5 | PC6 | PC7 | PC8 | PC9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Easy Navigation | 0.12 | −0.07 | −0.43 | −0.76 | 0.24 | 0.28 | 0.13 | 0.21 | 0.15 |

| Personalized Product Recommendations | 0.43 | −0.10 | 0.17 | −0.38 | −0.27 | −0.12 | −0.64 | −0.22 | −0.31 |

| Barcode Scanning for Instant Search | 0.07 | 0.423 | −0.60 | 0.23 | −0.06 | 0.34 | −0.07 | −0.46 | −0.25 |

| Virtual Fitting Rooms | 0.54 | −0.22 | 0.12 | 0.10 | −0.10 | 0.16 | 0.26 | −0.45 | 0.58 |

| AR Clothing Try-On | 0.50 | −0.33 | −0.05 | 0.22 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.38 | 0.27 | −0.59 |

| Chatting with Stylists | 0.17 | 0.53 | 0.23 | −0.28 | 0.24 | −0.47 | 0.42 | −0.26 | −0.17 |

| Real-Time Interaction with 3D Models | 0.37 | 0.12 | −0.30 | 0.29 | 0.49 | −0.39 | −0.38 | 0.26 | 0.27 |

| Recognizing Trends and Fashion Advice | 0.11 | 0.34 | 0.52 | 0.05 | 0.41 | 0.61 | −0.19 | 0.13 | −0.01 |

| Scanning Clothes for Similar Items | 0.28 | 0.48 | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.62 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.52 | 0.17 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sardianou, E.; Briana, M. Platform-Driven Sustainability in E-Commerce: Consumer Behavior Toward Recycled Fashion. Recycling 2025, 10, 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/recycling10040161

Sardianou E, Briana M. Platform-Driven Sustainability in E-Commerce: Consumer Behavior Toward Recycled Fashion. Recycling. 2025; 10(4):161. https://doi.org/10.3390/recycling10040161

Chicago/Turabian StyleSardianou, Eleni, and Maria Briana. 2025. "Platform-Driven Sustainability in E-Commerce: Consumer Behavior Toward Recycled Fashion" Recycling 10, no. 4: 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/recycling10040161

APA StyleSardianou, E., & Briana, M. (2025). Platform-Driven Sustainability in E-Commerce: Consumer Behavior Toward Recycled Fashion. Recycling, 10(4), 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/recycling10040161