Boron-Doped Bamboo-Derived Porous Carbon via Dry Thermal Treatment for Enhanced Electrochemical Performance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material Preparation and Boron Doping Procedures

2.2. Materials Characterization

2.3. Electrochemical Measurements

3. Results and Discussion

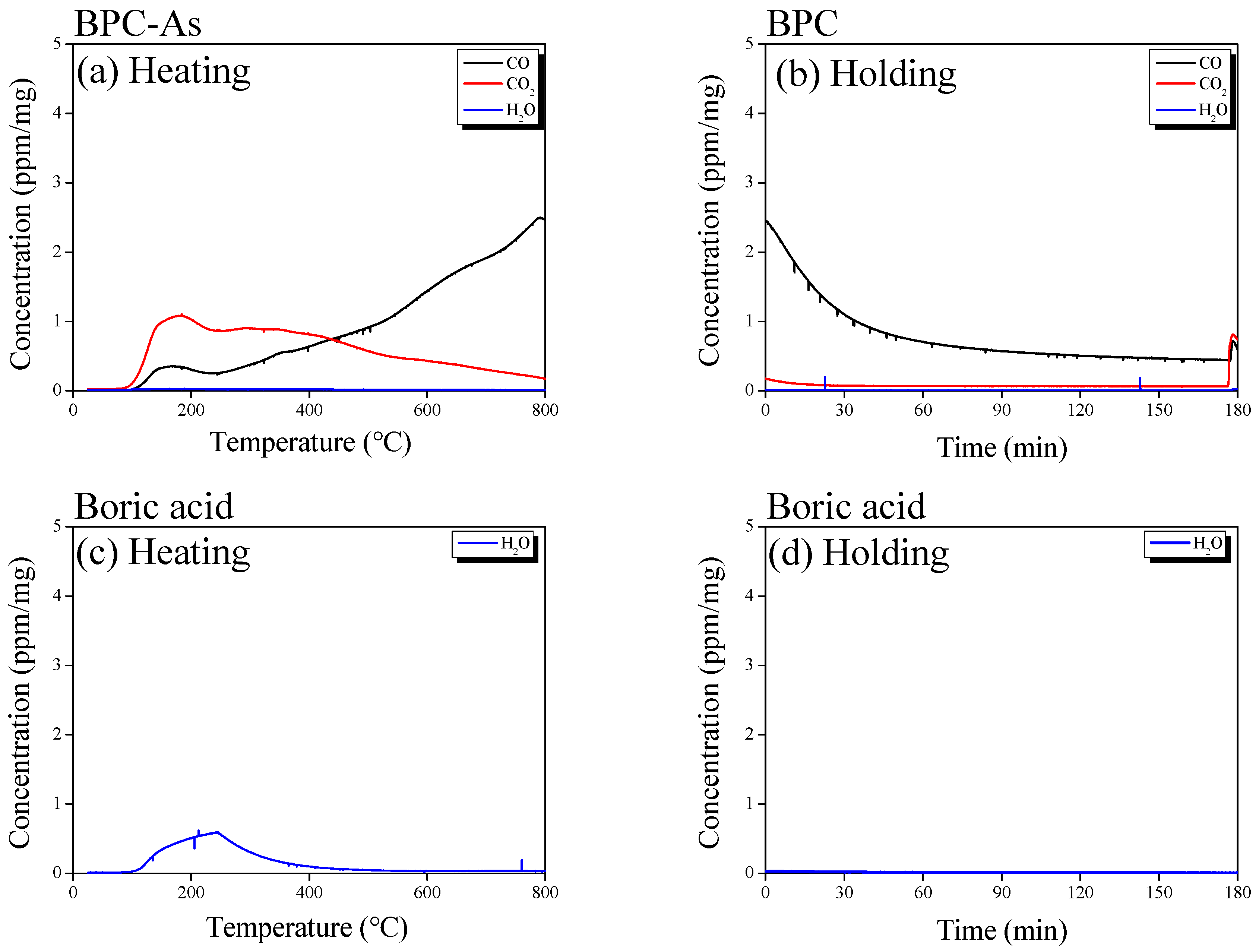

3.1. Boron Doping Mechanism and Surface Properties

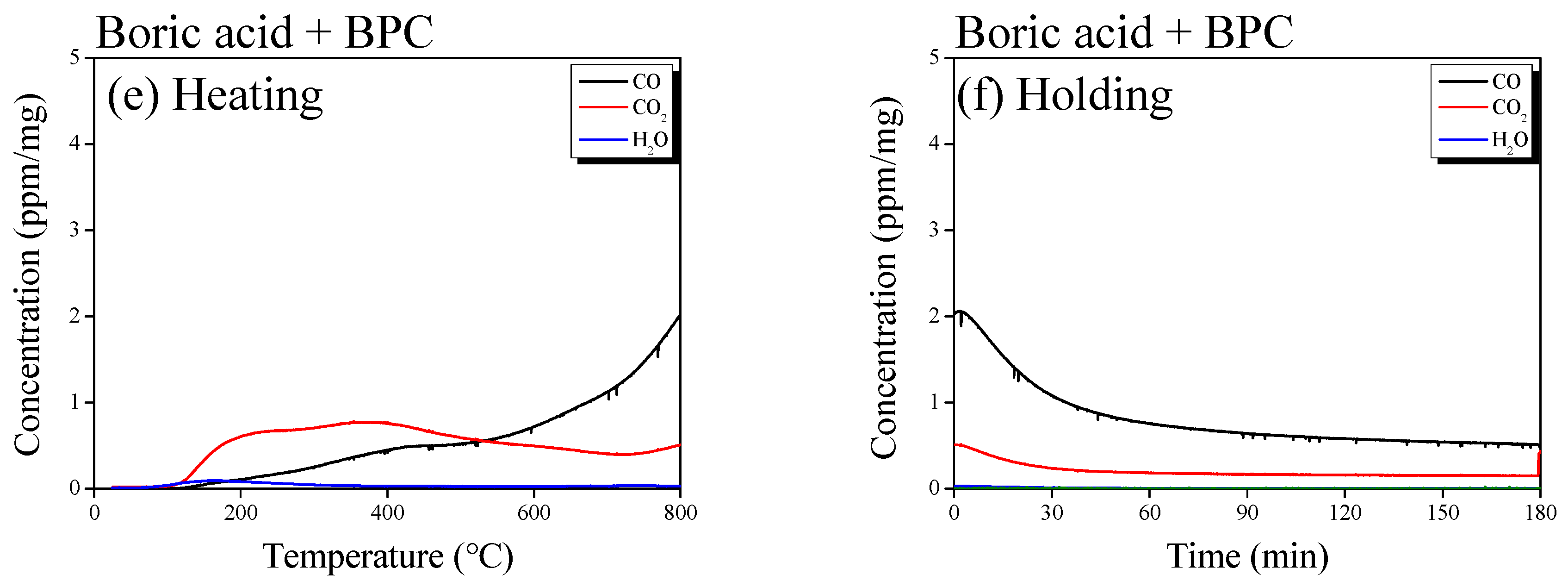

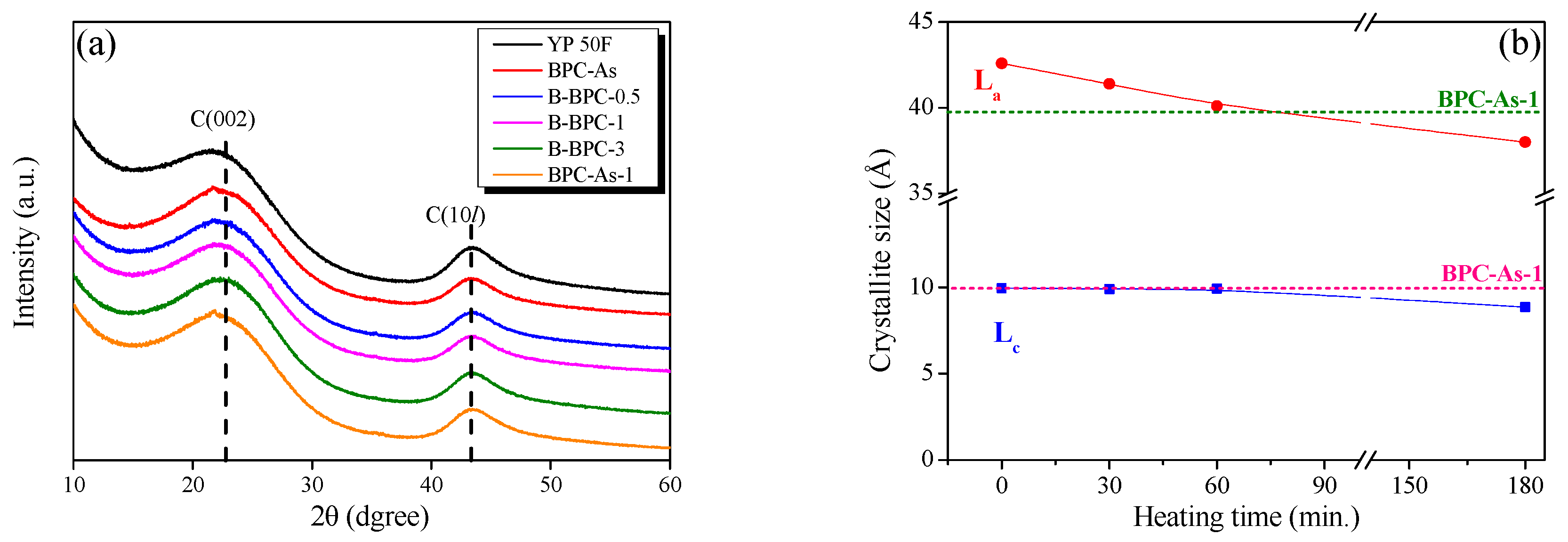

3.2. Crystallite Structure and Textural Properties

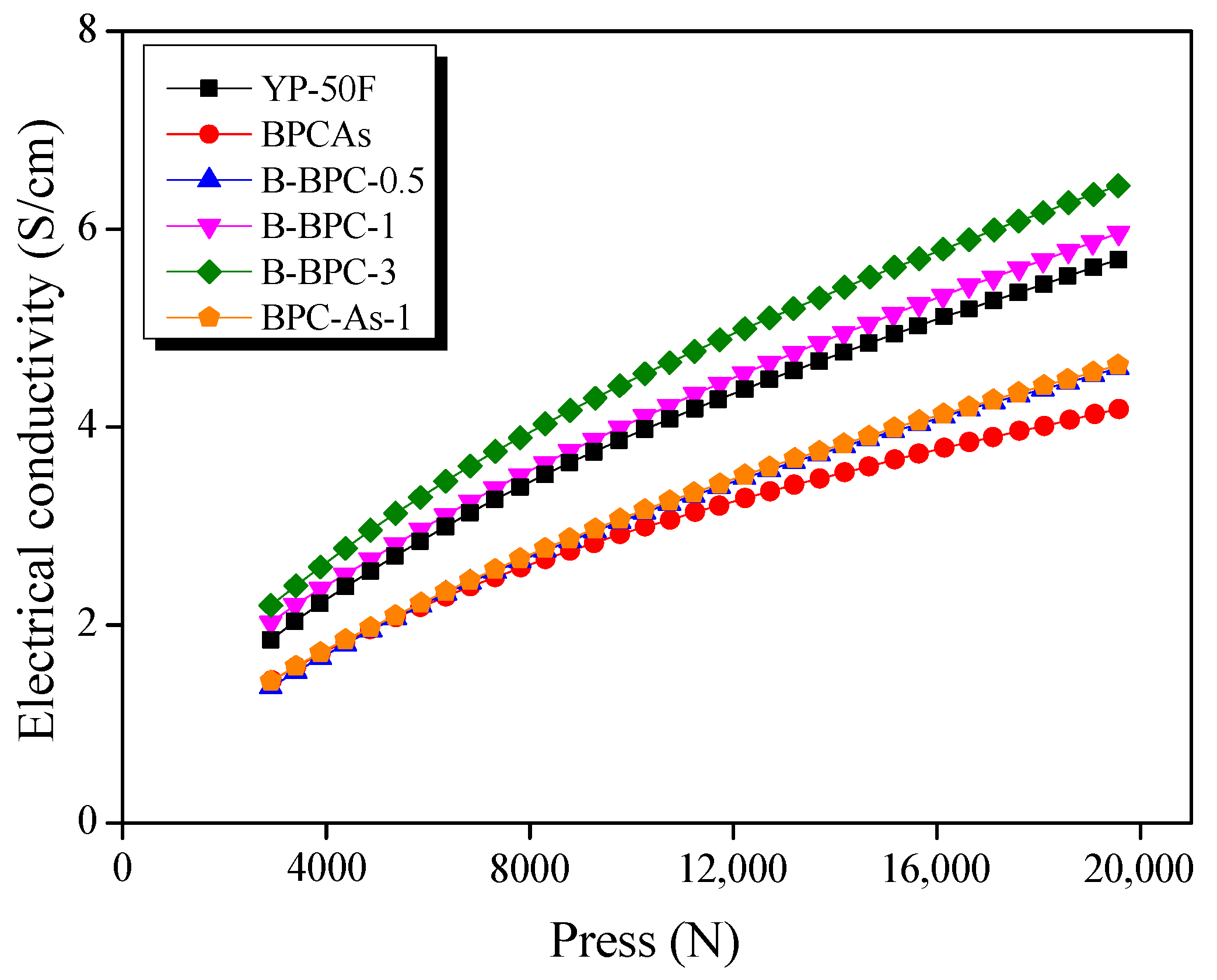

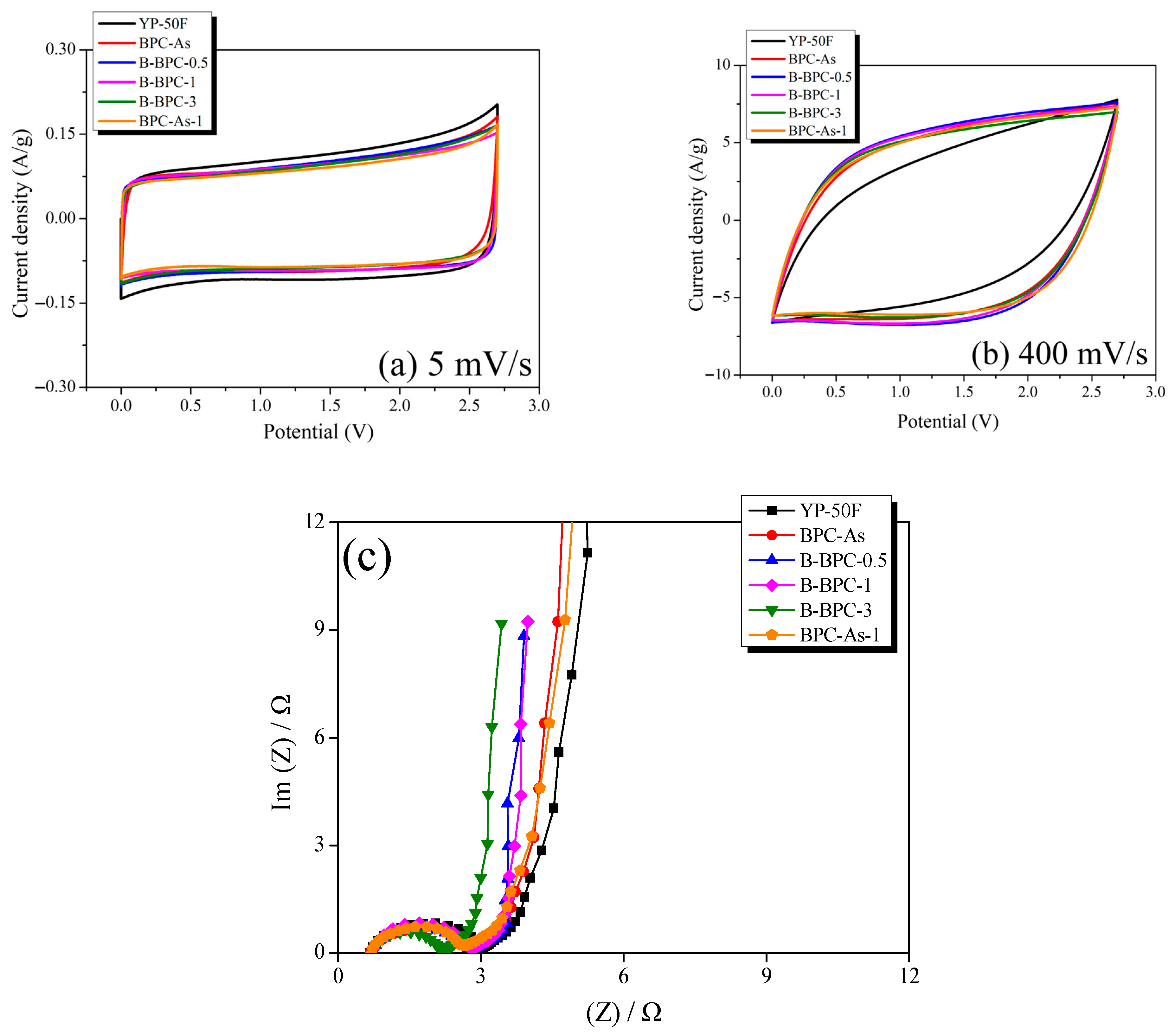

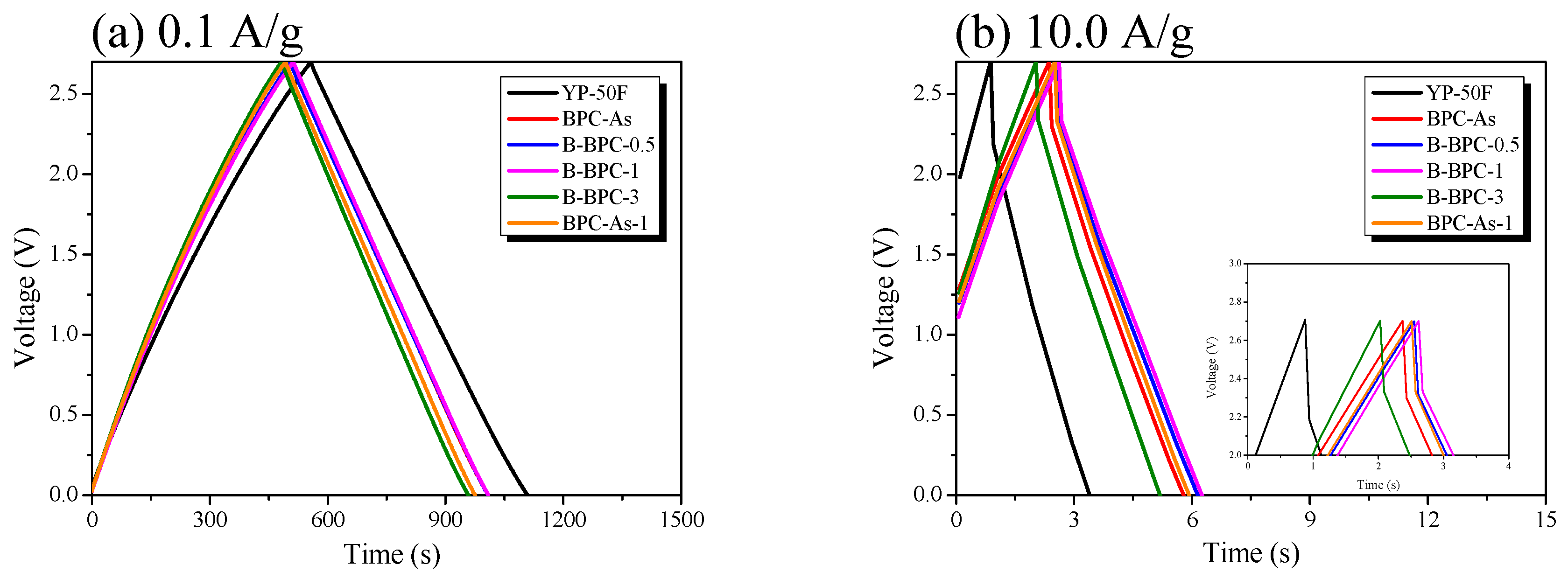

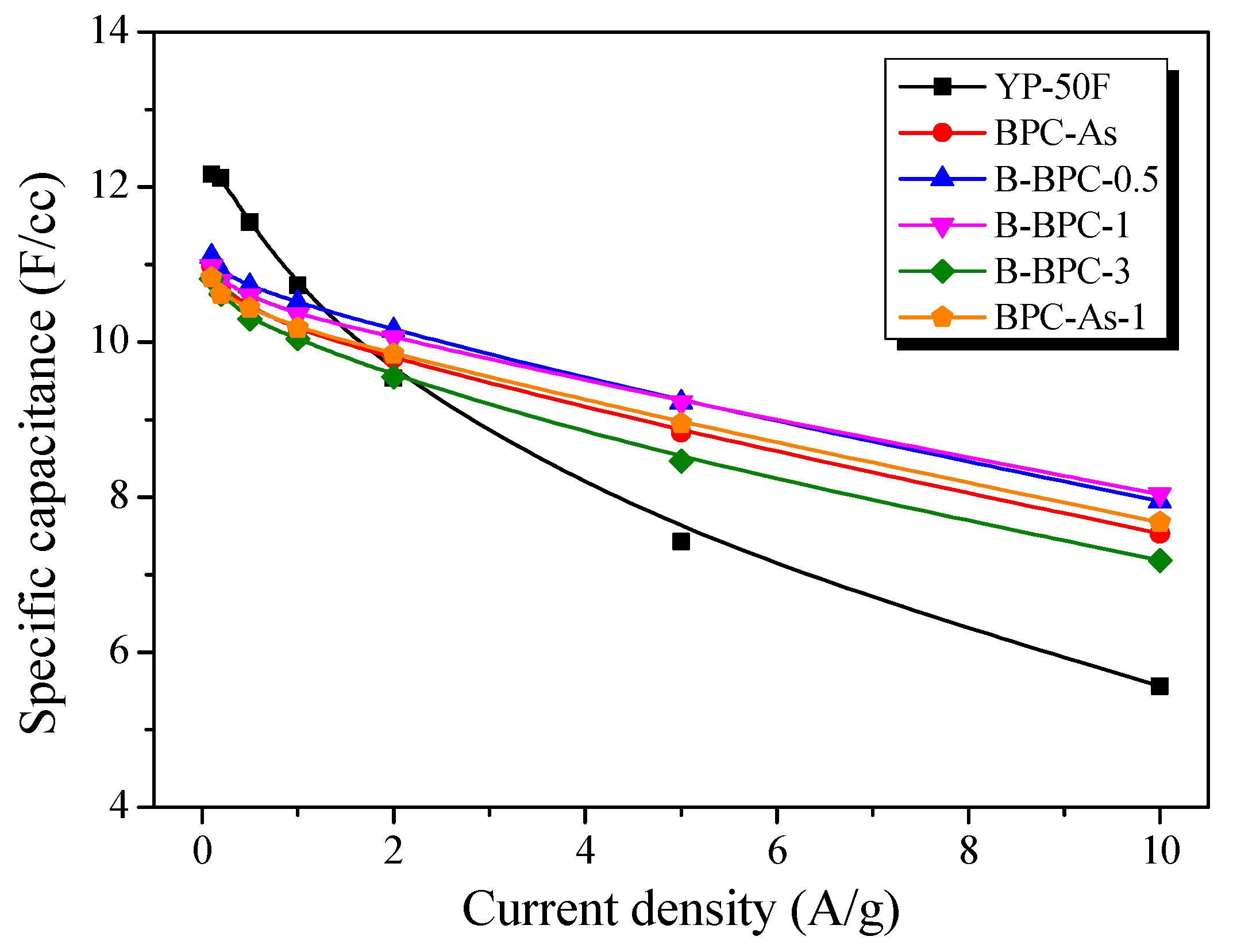

3.3. Electrochemical Properties

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, H.; Yan, Q.; Li, J.; Qiu, J.; Zhang, H. Porous Carbon Materials: From Traditional Synthesis, Machine Learning-Assisted Design, to Their Applications in Advanced Energy Storage and Conversion. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2504272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, D.; Zeng, Y.; Zhong, J.; Chen, J.; Ye, Y.; Wang, W. Ultra-high specific surface area porous carbons derived from Chinese medicinal herbal residues with potential applications in supercapacitors and CO2 capture. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2023, 666, 131327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Lee, H.M.; Jung, S.C.; Chung, D.C.; Kim, B.J. Bamboo-Based Mesoporous Activated Carbon for High-Power-Density Electric Double-Layer Capacitors. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zhang, Y.; Xing, G.; Chou, S.; Tang, Y. Electrochemical energy storage devices working in extreme conditions. Energy Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 3323–3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, A.R.; Muthusamy, A.; Inho-Cho; Kim, H.; Senthil, K.; Prabakar, K. Ultrahigh surface area biomass derived 3D hierarchical porous carbon nanosheet electrodes for high energy density supercapacitors. Carbon 2020, 174, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.M.; An, K.H.; Park, S.J.; Kim, B.J. Mesopore-Rich Activated Carbons for Electrical Double-Layer Capacitors by Optimal Activation Condition. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urita, K.; Urita, C.; Fujita, K.; Horio, K.; Yoshida, M.; Moriguchi, I. The ideal porous structure of EDLC carbon electrodes with extremely high capacitance. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 15643–15649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Hou, H.; Xu, W.; Duan, G.; He, S.; Liu, K.; Jiang, S. Recent progress in carbon-based materials for supercapacitor electrodes: A review. J. Mater. Sci. 2020, 56, 173–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frackowiak, É.; Beguin, F. Carbon materials for the electrochemical storage of energy in capacitors. Carbon 2001, 39, 937–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zheng, K.; Yang, D.; Ye, X.; Zhou, L.; Yun, J. Construction of metal-free heteroatoms doped carbon catalysts with certain structure and properties: Strategies and methods. Carbon Lett. 2025, 35, 963–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.H.; Park, S.H.; Woo, S.I. Binary and Ternary Doping of Nitrogen, Boron, and Phosphorus into Carbon for Enhancing Electrochemical Oxygen Reduction Activity. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 7084–7091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Li, F.; Chen, Z.; Lu, G.Q.; Cheng, H. Synthesis and Electrochemical Property of Boron-Doped Mesoporous Carbon in Supercapacitor. Chem. Mater. 2008, 20, 7195–7200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnoli, S.; Favaro, M. Doping graphene with boron: A review of synthesis methods, physicochemical characterization, and emerging applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 5002–5025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biscoe, J.; Warren, B.E. An X-Ray Study of Carbon Black. J. Appl. Phys. 1942, 13, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunauer, S.; Emmett, P.H.; Teller, E. Adsorption of Gases in Multimolecular Layers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1938, 60, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, E.P.; Joyner, L.G.; Halenda, P.P. The Determination of Pore Volume and Area Distributions in Porous Substances. I. Computations from Nitrogen Isotherms. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1951, 73, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neimark, A.V.; Lin, Y.; Ravikovitch, P.I.; Thommes, M. Quenched solid density functional theory and pore size analysis of micro-mesoporous carbons. Carbon 2009, 47, 1617–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galarneau, A.; Villemot, F.; Rodriguez, J.; Fajula, F.; Coasne, B. Validity of the t-plot Method to Assess Microporosity in Hierarchical Micro/Mesoporous Materials. Langmuir 2014, 30, 13266–13274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herold, F.; Gläsel, J.; Etzold, B.J.M.; Rønning, M. Can Temperature-Programmed Techniques Provide the Gold Standard for Carbon Surface Characterization? Chem. Mater. 2022, 34, 8490–8516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, B.J.; Lee, H.M. Effects of Oxygen-Containing Functional Groups on the Electrochemical Performance of Activated Carbon for EDLCs. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohl, S.; Drochner, A.; Vogel, H. Quantification of oxygen surface groups on carbon materials via diffuse reflectance FT-IR spectroscopy and temperature programmed desorption. Catal. Today 2010, 150, 67–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, J.L.; Pereira, M.F.R.; Freitas, M.M.A.; Orfao, J.J.M. Modification of the surface chemistry of activated carbons. Carbon 1999, 37, 1379–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozień, D.; Jeleń, P.; Stępień, J.; Olejniczak, Z.; Sitarz, M.; Pędzich, Z. Surface Properties and Morphology of Boron Carbide Nanopowders Obtained by Lyophilization of Saccharide Precursors. Materials 2021, 14, 3419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotaru, A. Thermal and kinetic study of hexagonal boric acid versus triclinic boric acid in air flow. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2016, 127, 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Xiong, Y.; Yu, T.; Zhu, P.; Yan, X.; Wang, Z.; Guan, S. Boron and nitrogen co-doped porous carbon with a high concentration of boron and its superior capacitive behavior. Carbon 2016, 113, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesavan, D.; Mariappan, V.K.; Krishnamoorthy, K.; Kim, S.J. Carbothermal conversion of boric acid into boron-oxy-carbide nanostructures for high-power supercapacitors. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 9, 915–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, B.; Martin, H.; Michaelis, A. Synthesis of Boron Carbide Powder via Rapid Carbothermal Reduction Using Boric Acid and Carbonizing Binder. Ceramics 2022, 5, 837–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.H.; An, K.H.; Kim, B.J. Preparation of Mesoporous Boron-Doped Porous Carbon Derived from Coffee Grounds via Hybrid Activation for Carbon Capture and Storage. Batteries 2025, 11, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesnokov, V.V.; Prosvirin, I.P.; Gerasimov, E.Y.; Chichkan, A.S. Synthesis of Boron-Doped Carbon Nanomaterial. Materials 2023, 16, 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Chen, H.; Zhang, W.; Yi, S.; Chen, H.; Su, Z.; Niu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Long, D. Defect engineering in carbon materials for electrochemical energy storage and catalytic conversion. Mater. Adv. 2023, 4, 835–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.J.; Lee, H.M.; An, K.H.; Kim, B.J. Preparation of polyimide-based activated carbon fibers and their application as the electrode materials of electric double-layer capacitors. Carbon Lett. 2024, 34, 1653–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allagui, A.; Freeborn, T.J.; Elwakil, A.S.; Maundy, B.J. Reevaluation of Performance of Electric Double-layer Capacitors from Constant-current Charge/Discharge and Cyclic Voltammetry. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 38568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.H.; Kim, J.H.; Jeong, J.S.; Lee, H.M.; An, K.H.; Kim, B.J. Electrochemical performance of microporous carbons derived from oak wood for electric double-layer capacitor. Carbon Lett. 2025, 35, 2381–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pati, S.K.; Hwang, Y.; Lee, H.M.; Kim, B.J.; Park, S.J. Porous activated carbon derived from petroleum coke as a high-performance anodic electrode material for supercapacitors. Carbon Lett. 2023, 34, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazanas, A.C.; Prodromidis, M.I. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy—A Tutorial. ACS Meas. Sci. Au 2023, 3, 162–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick, J.S.J.; Subrayapillai Ramakrishna, N.; Sankar, M.; Joseph, M.; Moses, V.A.R.; Saravanabhavan, S.S.; Appusamy, M.; Ayyar, M. Examination of hybrid electrode material for energy storage device supercapacitor under various electrolytes. Carbon Lett. 2024, 34, 1639–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z.; Chen, H.; Yang, M.; Yang, D.; Li, H. Boron and oxygen-codoped porous carbon as efficient oxygen reduction catalysts. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 426, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Barg, S.; Jeong, S.M.; Ostrikov, K. Heteroatom-Doped and Oxygen-Functionalized Nanocarbons for High-Performance Supercapacitors. Adv. Energy Mater. 2020, 10, 2001239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya, A.A. A physically consistent electric circuit to interpret the galvanostatic charge-discharge curves of electric double layer capacitors. J. Power Sources 2025, 656, 238050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavil, J.; Anjana, P.M.; Joshy, D.; Babu, A.; Raj, G.; Periyat, P.; Rakhi, R.B. g-C3N4/CuO and g-C3N4/Co3O4 nanohybrid structures as efficient electrode materials in symmetric supercapacitors. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 38430–38437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duraisamy, N.; Shenniangirivalasu Kandasamy, K.; Dhandapani, E.; Kandiah, K.; Panchu, S.J.; Swart, H.C. Biomass Derived 3D Hierarchical Porous Activated Carbon for Solid-State Symmetric Supercapacitors. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. 2025, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Yu, J.; Yang, X.; Zhang, G. Activated Carbon Fibers with Hierarchical Nanostructure Derived from Waste Cotton Gloves as High-Performance Electrodes for Supercapacitors. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample | SBET a (m2/g) | VTotal b (cm3/g) | VMicro c (cm3/g) | Vmeso d (cm3/g) | RMicro e | RMesof |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YP-50F | 1710 | 0.79 | 0.62 | 0.17 | 0.78 | 0.22 |

| BPC-As | 1490 | 0.73 | 0.44 | 0.29 | 0.60 | 0.40 |

| B-BPC-0.5 | 1540 | 0.76 | 0.46 | 0.30 | 0.61 | 0.39 |

| B-BPC-1 | 1560 | 0.77 | 0.47 | 0.30 | 0.61 | 0.39 |

| B-BPC-3 | 1540 | 0.76 | 0.46 | 0.30 | 0.61 | 0.39 |

| BPC-As-1 | 1510 | 0.74 | 0.45 | 0.29 | 0.61 | 0.39 |

| Sample | IR Drop (V) |

|---|---|

| YP-50F | 0.521 |

| BPC-As | 0.402 |

| B-BPC-0.5 | 0.383 |

| B-BPC-1 | 0.369 |

| B-BPC-3 | 0.372 |

| BPC-As-1 | 0.373 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, H.-H.; Cho, C.-K.; Kim, J.-H.; Lee, H.-M.; An, K.-H.; Chung, D.-C.; Kim, B.-J. Boron-Doped Bamboo-Derived Porous Carbon via Dry Thermal Treatment for Enhanced Electrochemical Performance. Batteries 2025, 11, 443. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries11120443

Kim H-H, Cho C-K, Kim J-H, Lee H-M, An K-H, Chung D-C, Kim B-J. Boron-Doped Bamboo-Derived Porous Carbon via Dry Thermal Treatment for Enhanced Electrochemical Performance. Batteries. 2025; 11(12):443. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries11120443

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Hyeon-Hye, Cheol-Ki Cho, Ju-Hwan Kim, Hye-Min Lee, Kay-Hyeok An, Dong-Cheol Chung, and Byung-Joo Kim. 2025. "Boron-Doped Bamboo-Derived Porous Carbon via Dry Thermal Treatment for Enhanced Electrochemical Performance" Batteries 11, no. 12: 443. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries11120443

APA StyleKim, H.-H., Cho, C.-K., Kim, J.-H., Lee, H.-M., An, K.-H., Chung, D.-C., & Kim, B.-J. (2025). Boron-Doped Bamboo-Derived Porous Carbon via Dry Thermal Treatment for Enhanced Electrochemical Performance. Batteries, 11(12), 443. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries11120443