Battery Passport and Online Diagnostics for Lithium-Ion Batteries: A Technical Review of Materials–Diagnostics Interactions and Online EIS

Abstract

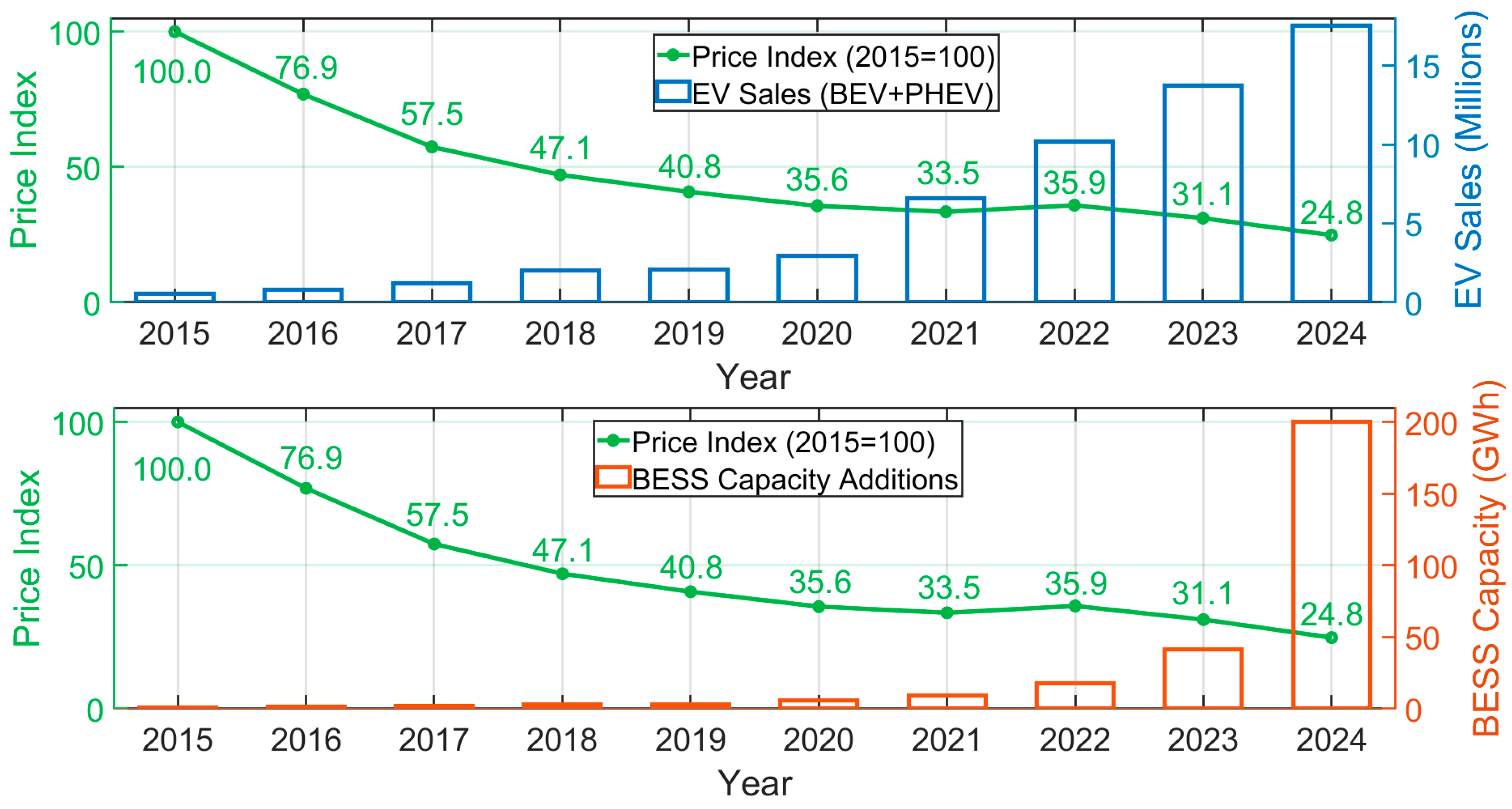

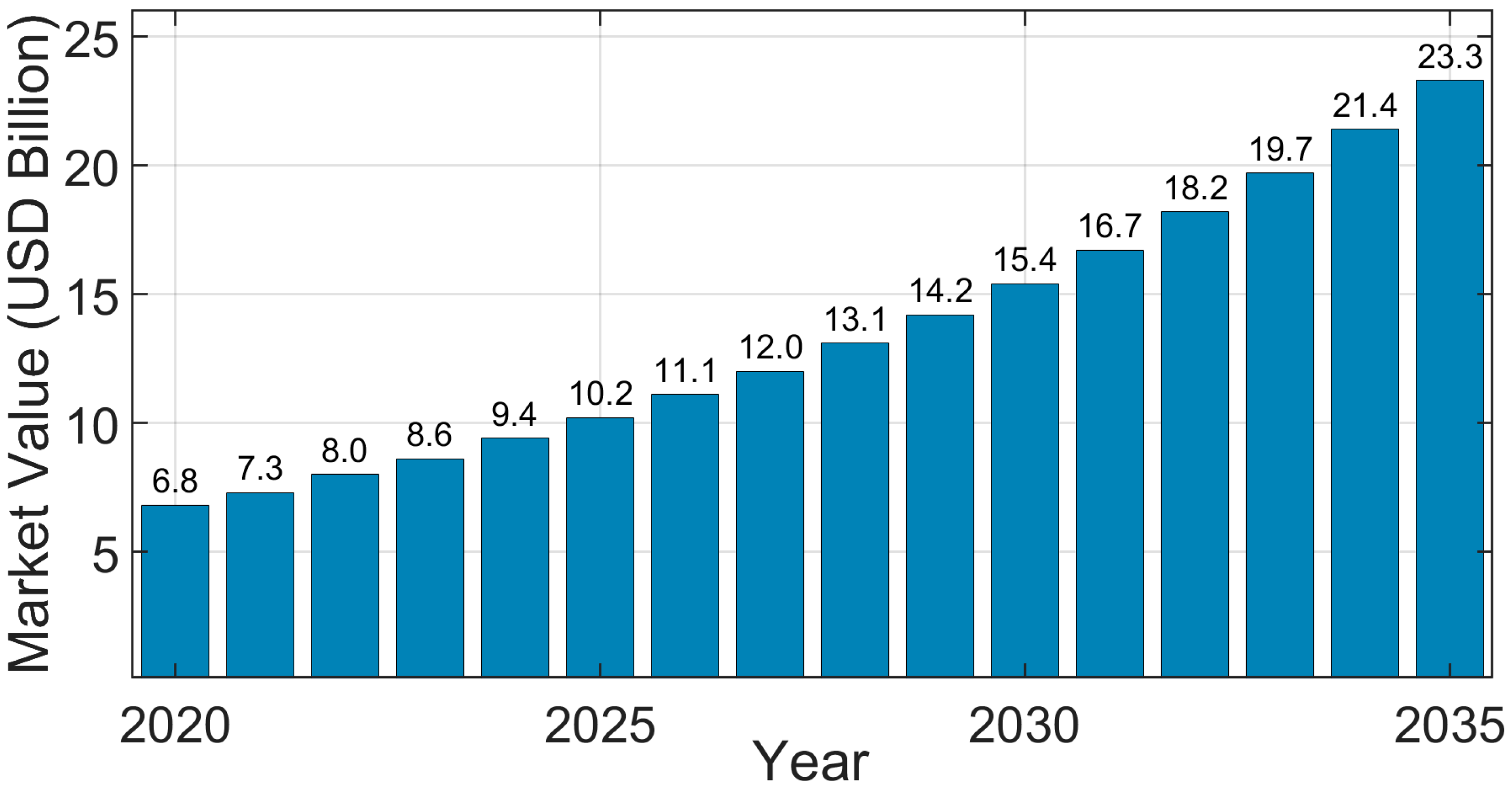

1. Introduction

2. Battery Passport

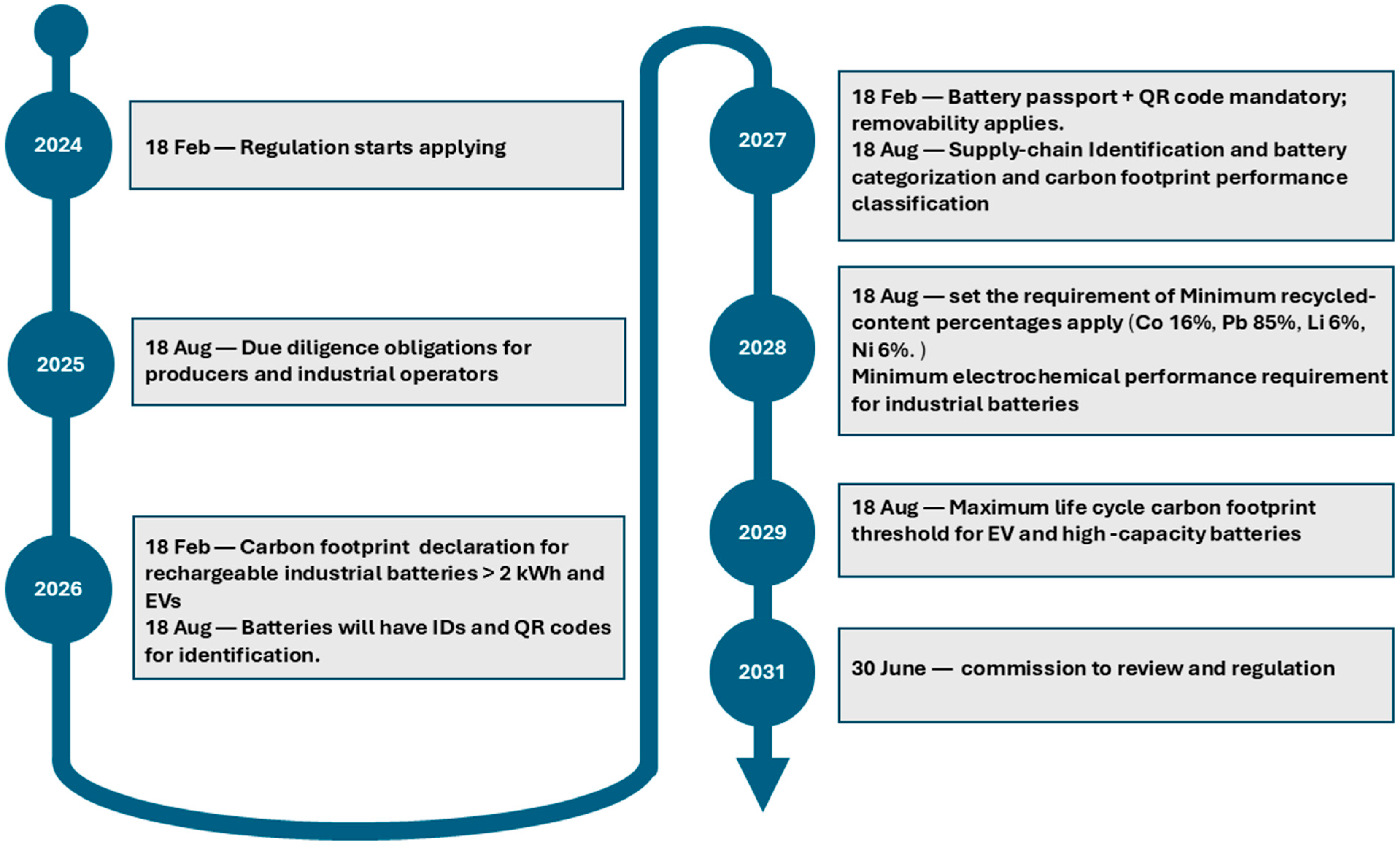

2.1. Battery Passport Purpose and Regulatory Framework

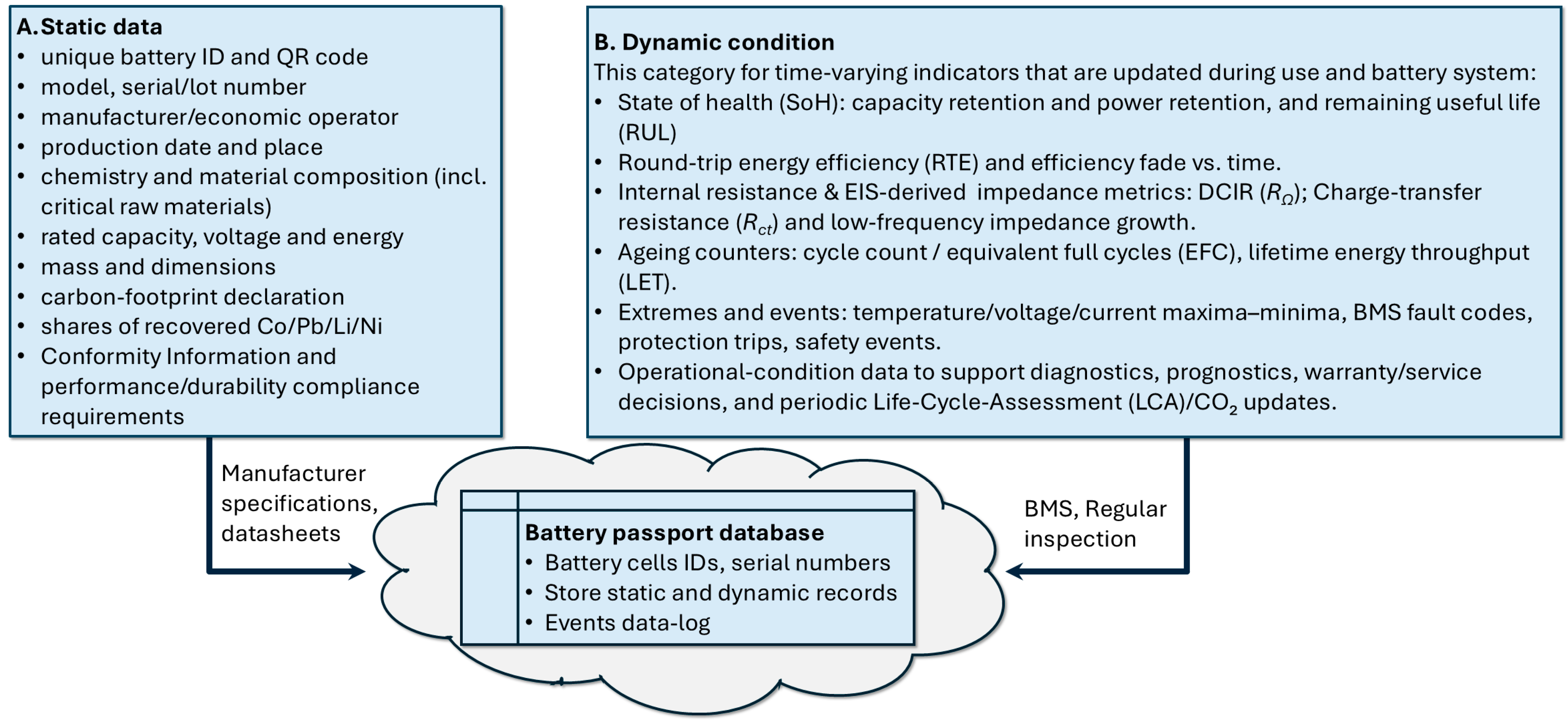

2.2. Data Model and Materials Traceability

2.3. Condition Reporting, Chemistry-Aware Indicators, and Lifecycle Updates

2.4. BMS Interoperability Challenges

2.5. Economic Feasibility

2.6. Comparison of EU, USA, and Chinese Frameworks for Battery Passports

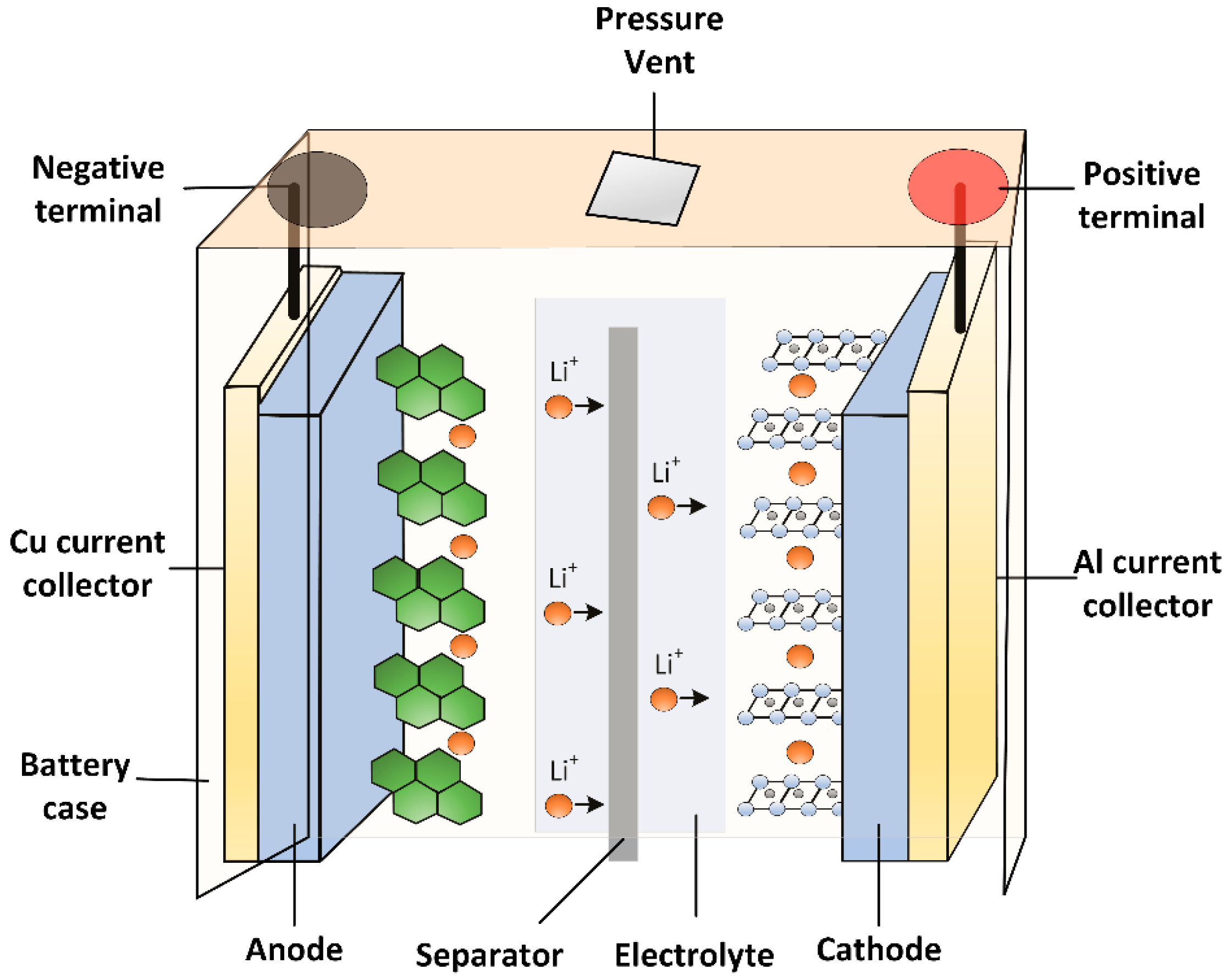

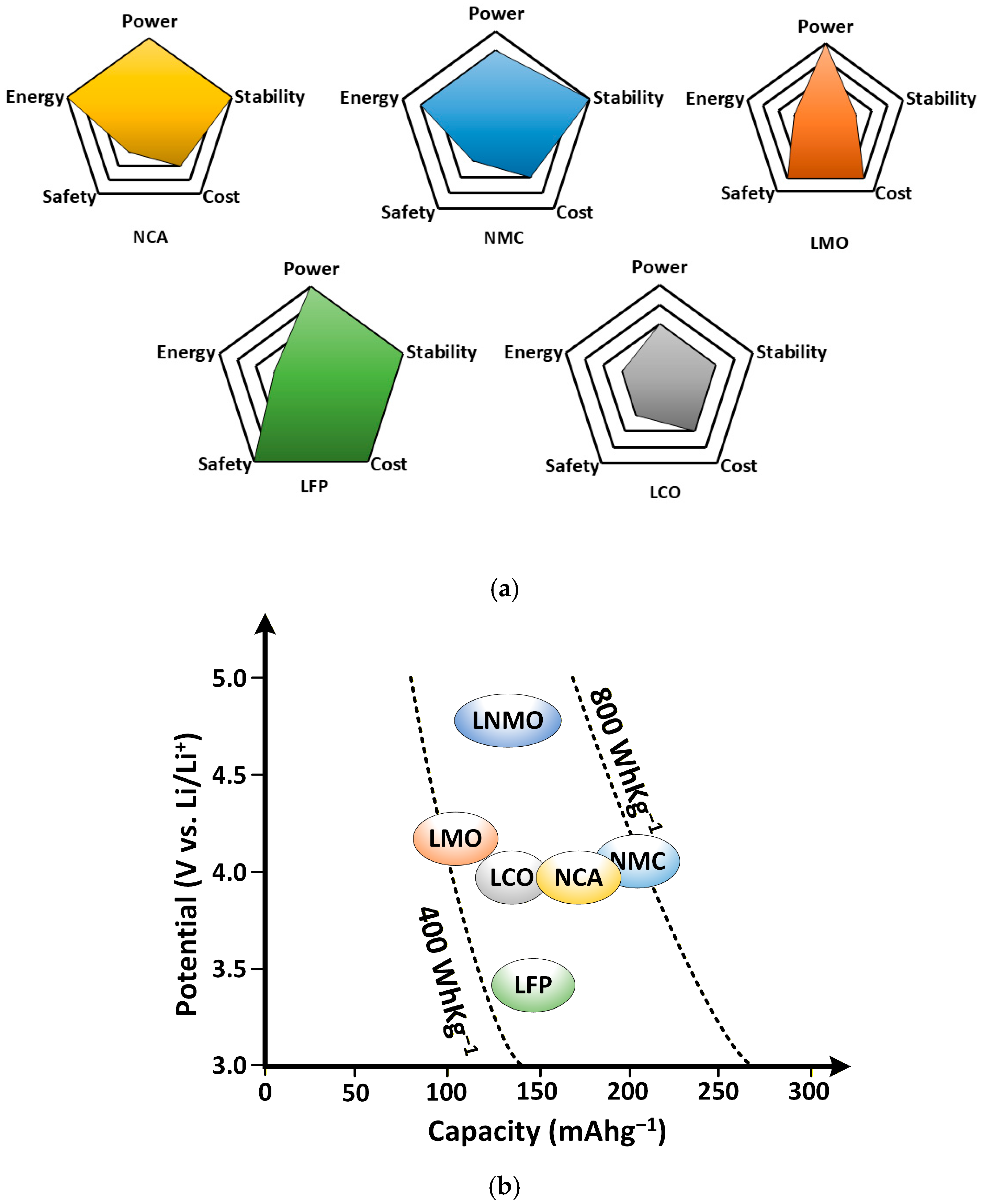

3. Fundamentals of Li-Ion Battery and Its Categories

3.1. LCO Chemistry

3.2. NCA Chemistry

3.3. NMC Chemistry

3.4. LMO Chemistry

3.5. LFP Chemistry

3.6. Anode Materials for Battery Technology

3.7. Electrolyte Materials for Battery Technology

3.8. Separator Materials for Battery Technology

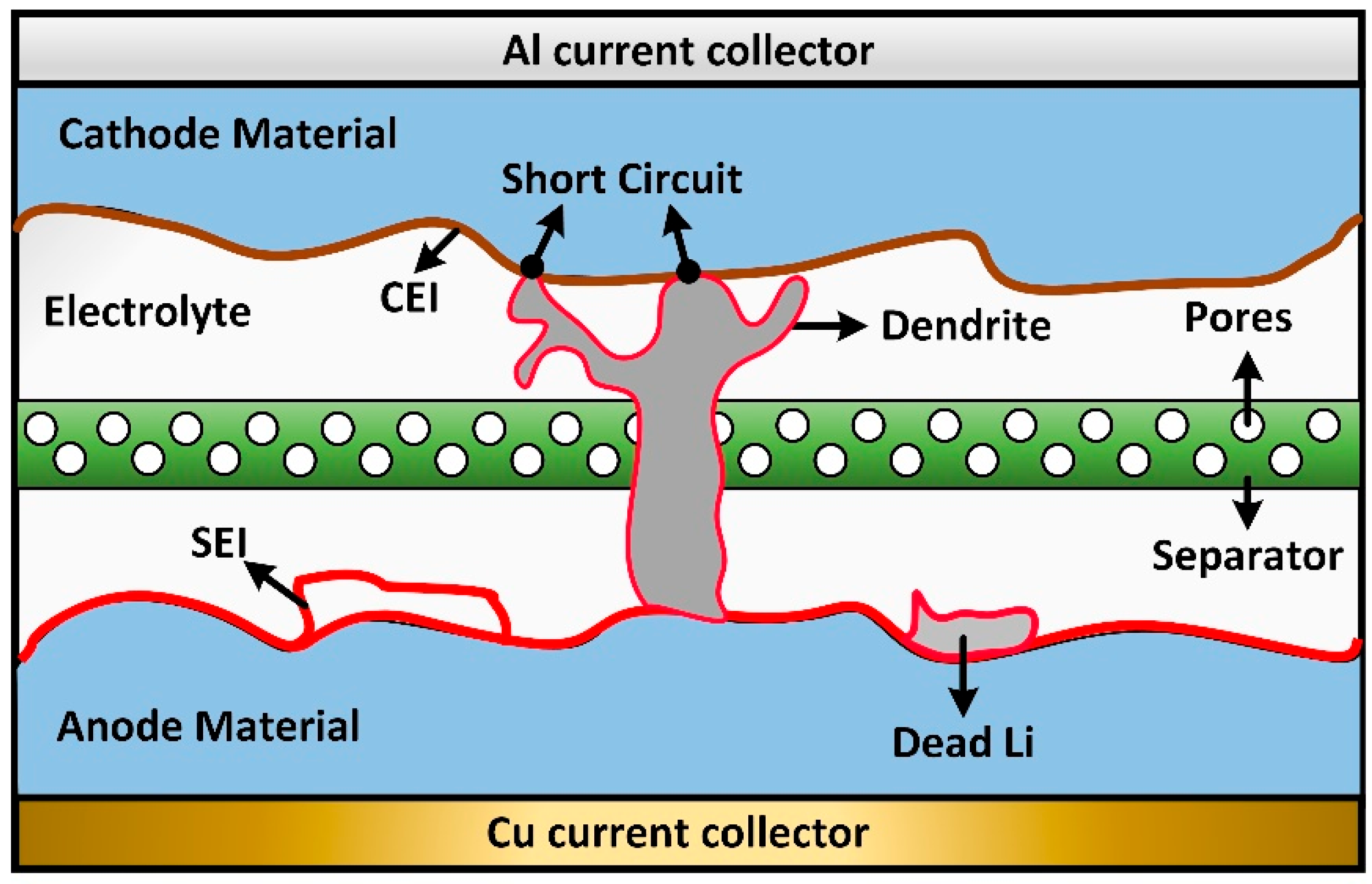

4. Lithium Plating and Interfacial Layer Formation

4.1. Lithium Plating

4.2. Solid Electrolyte Interphase (SEI)

4.3. Cathode Electrolyte Interphase (CEI)

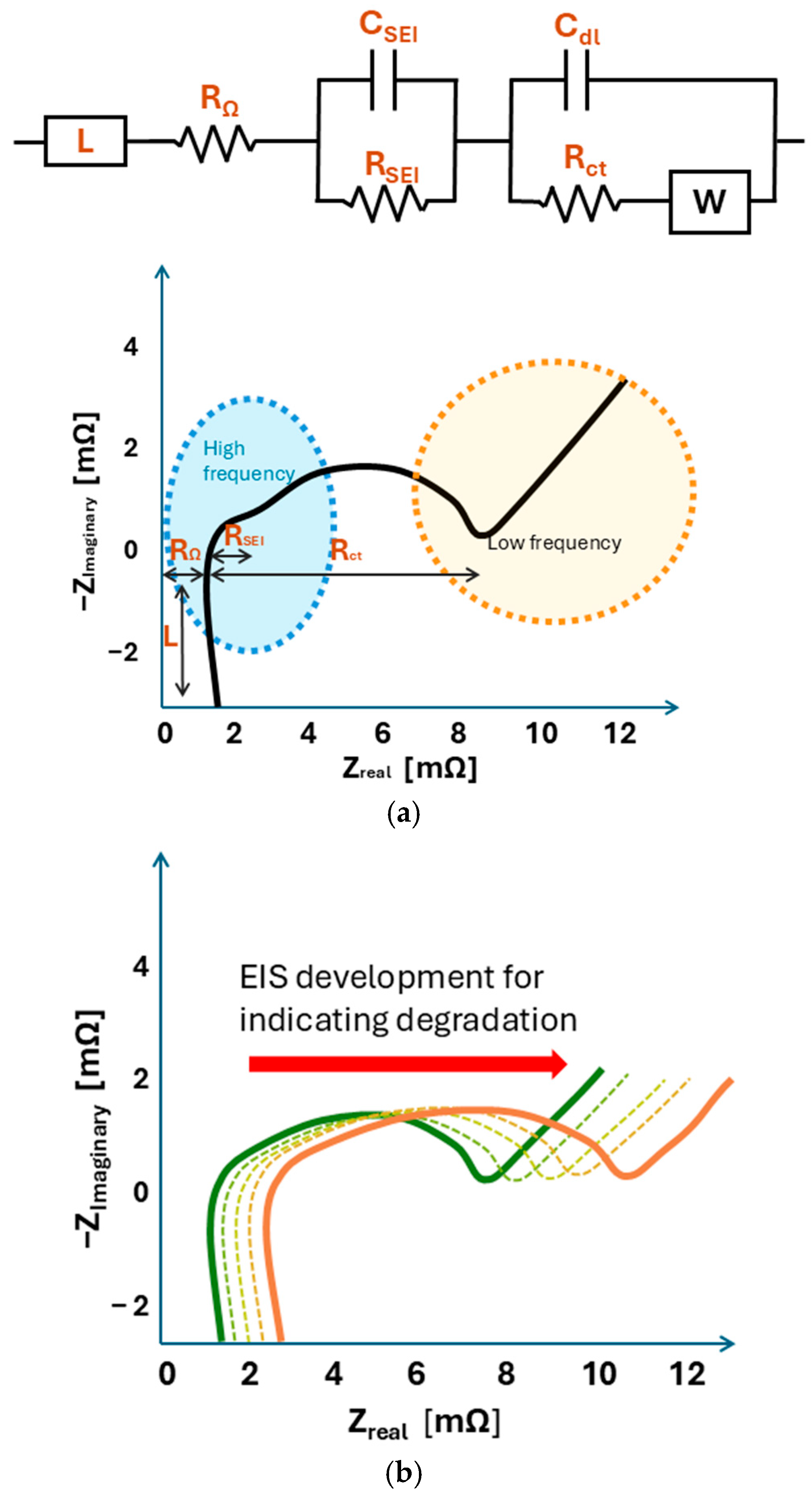

5. Online EIS for Lithium-Ion Battery Diagnostics

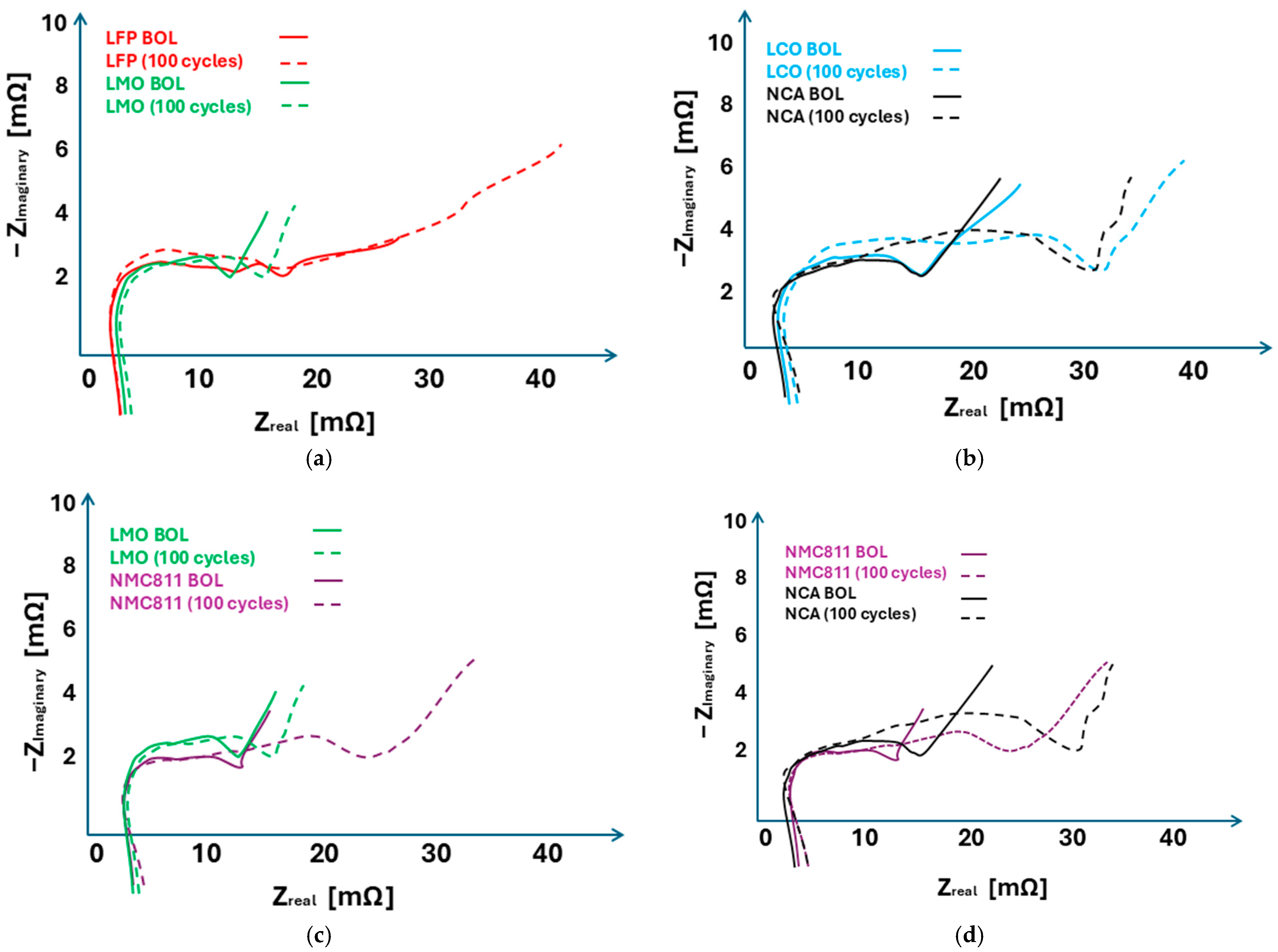

5.1. Degradation Indicators from EIS

5.2. EIS Indicators for Comparison of LIB Chemistries

Comparison of NCA and NMC: EIS Indicators

5.3. Standardization Gaps in Converting Raw EIS to Chemistry-Aware Indicators

5.3.1. Causes of Non-Harmonization

5.3.2. Metadata Needs and Parameters

5.3.3. Existing Standards and Initiatives

5.3.4. Practical Recommendations for Future Standardization

5.4. Real-Time Implementation on Operational Systems

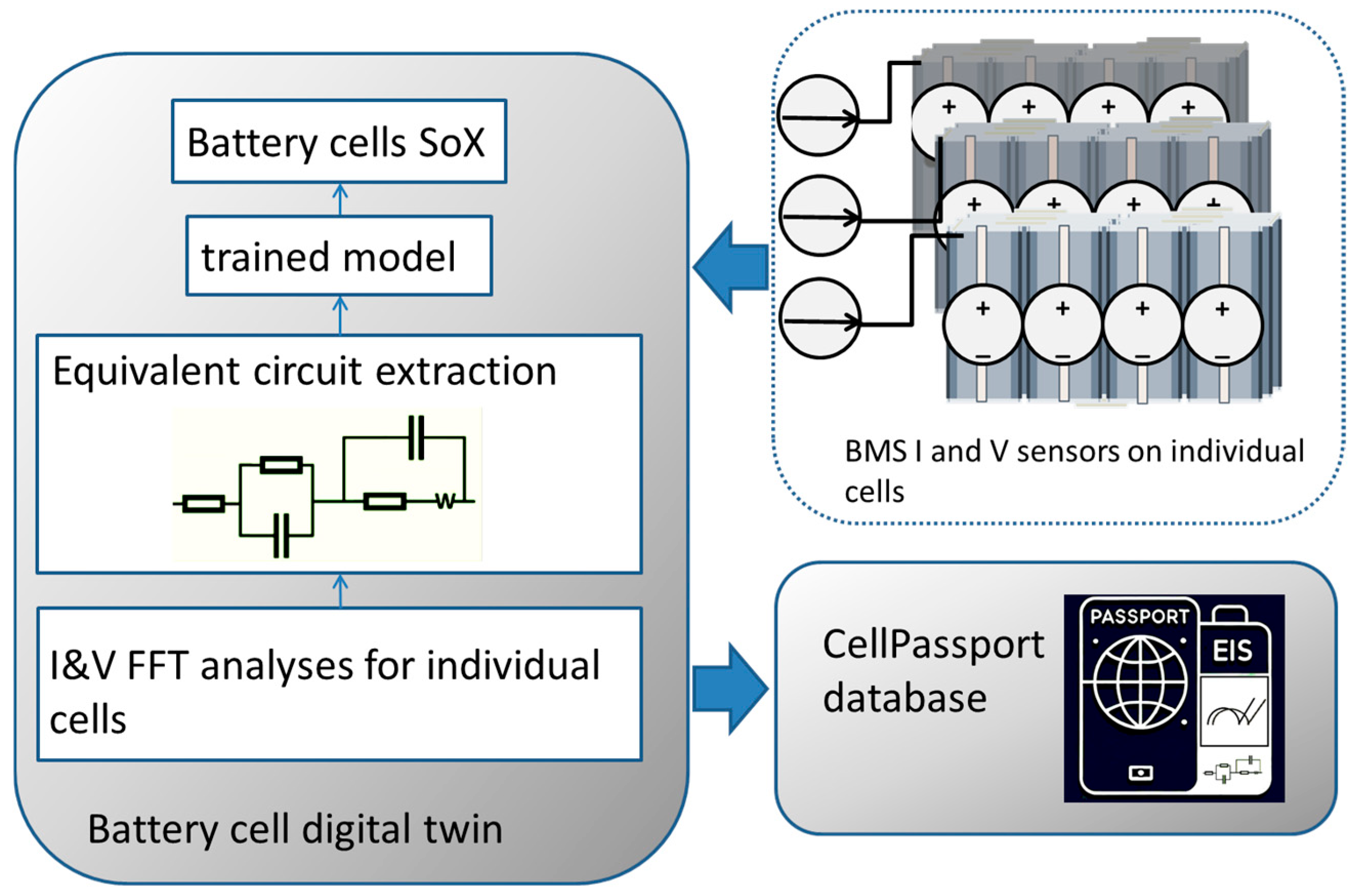

5.5. Online EIS: Architecture and Workflow

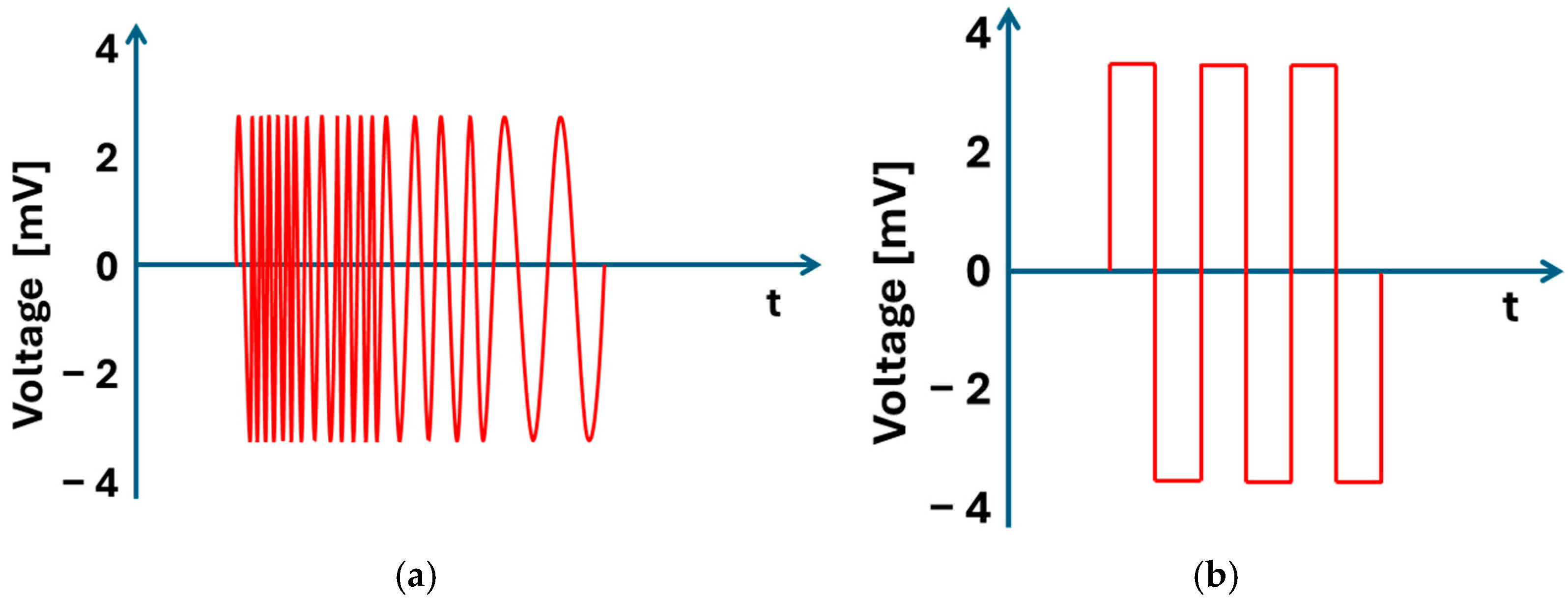

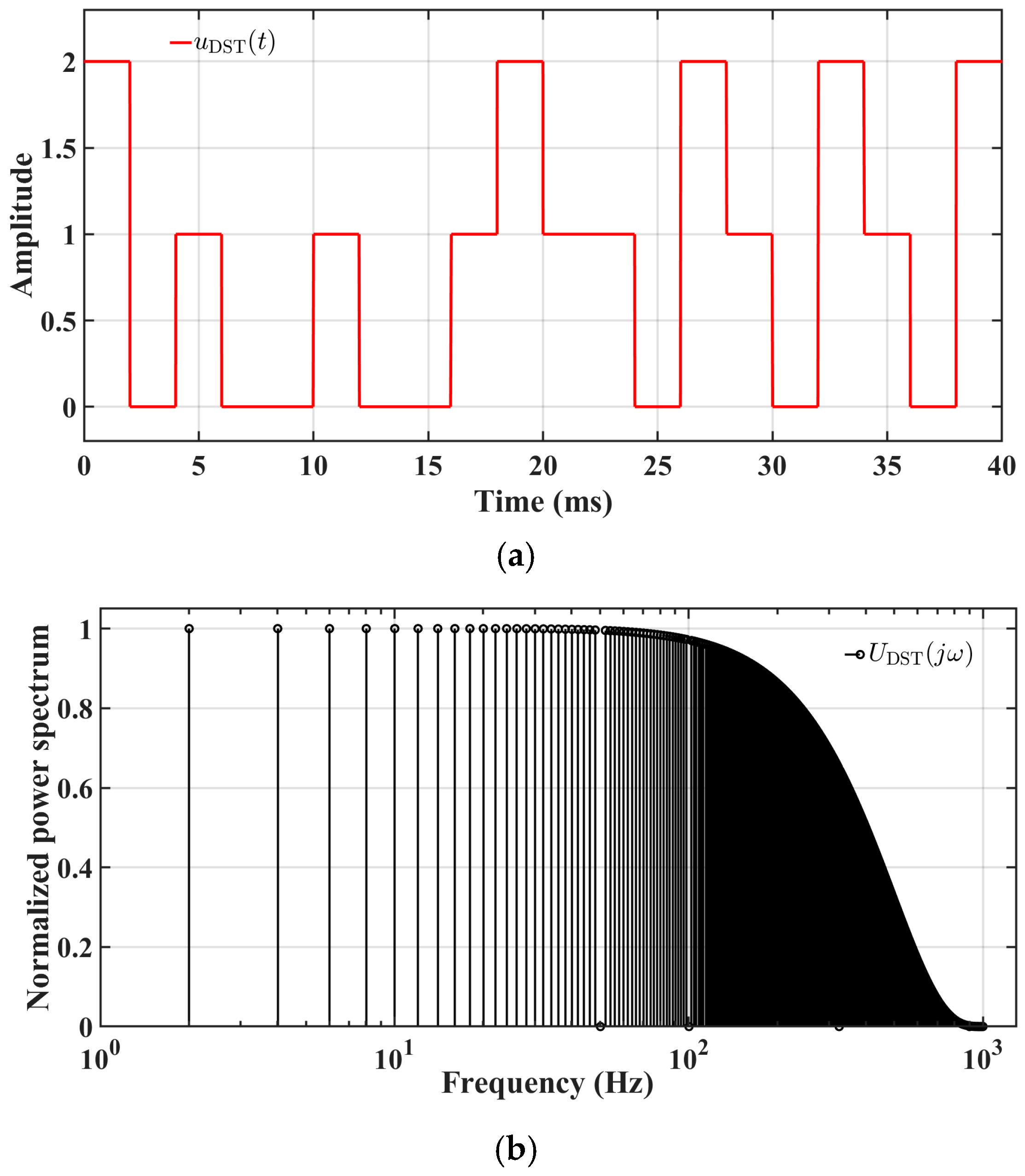

5.5.1. Passive EIS Testing

5.5.2. Cloud-Based EIS Battery Diagnostic

5.6. Adaptation of Machine Learning Models for Real-World Battery Diagnostics

5.7. Cybersecurity Considerations for Battery Passports

6. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IEA. Global EV Outlook 2025; IEA: Paris, France, 2025; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2025 (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Jaspers, W.; Holöchter, N.; Krauß, J.; Becker, B.; Kampker, A. Target group-orientated sharing of production data in battery cell production: Enabling the battery passport. Procedia CIRP 2025, 134, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popowicz, M.; Pohlmann, A.; Schöggl, J.; Baumgartner, R.J. Digital Product Passports as Information Providers for Consumers—The Case of Digital Battery Passports. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2025, 34, 7700–7722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, M.U.; Sangwongwanich, A.; Stroe, D.; Blaabjerg, F. The Effect of Multi-Stage Constant Current Charging on Lithium-ion Battery’s Performance. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 17th International Conference on Compatibility, Power Electronics and Power Engineering (CPE-POWERENG), Tallinn, Estonia, 14–16 June 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Tahir, M.U.; Chakraborty, S.; Akboy, E.; Sangwongwanich, A.; Stroe, D.I.; Hegazy, O.; Blaabjerg, F. System-Level Performance Analysis of Li-Ion Batteries and DC–DC Converters Under Various Charging Strategies. IEEE Open J. Power Electron. 2025, 6, 1674–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, S.; Bleken, F.L.; Stier, S.; Flores, E.; Andersen, C.W.; Marcinek, M.; Szczesna-Chrzan, A.; Gaberscek, M.; Palacin, M.R.; Uhrin, M. Toward a unified description of battery data. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022, 12, 2102702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassini, M.; Redondo-Iglesias, E.; Venet, P. Battery passports for second-life batteries: An experimental assessment of suitability for mobile applications. Batteries 2024, 10, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rettenmeier, M.; Petrik, D.; Glinder, P.; Charlet, M.; Möller, M.; Wagenmann, S.; Thomas, S.; Krause, A.; Sauer, A. Business model framework for end-of-life automotive traction battery recycling. Procedia CIRP 2025, 134, 1029–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S. Battery Management System Market Report—Growth & Forecast 2025–2035. 2025. Available online: https://www.futuremarketinsights.com/reports/battery-management-system-market (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Rufino Júnior, C.A.; Riva Sanseverino, E.; Gallo, P.; Koch, D.; Diel, S.; Walter, G.; Trilla, L.; Ferreira, V.J.; Pérez, G.B.; Kotak, Y. Towards to battery digital passport: Reviewing regulations and standards for second-life batteries. Batteries 2024, 10, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gieß, A.; Möller, F. Exploring the value ecosystem of digital product passports. J. Ind. Ecol. 2025, 29, 561–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri, A.; Butturi, M.A.; Sauer, H.L.; Lolli, F.; Gamberini, R.; Sellitto, M.A. Distributed Ledger Technology selection for Digital Battery Passport: A BWM-TOPSIS approach. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2024, 58, 480–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saez de Bikuña, K.; Pierobon, M.; Soldati, C.; Vale, M.; Picone, N. Repurposing of Electric Vehicle Batteries for Second Life Stationary Applications in Residential Photovoltaic Systems: An Environmental and Economic Sustainability Assessment. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2025, 19, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemi, T.; Kaarlela, T.; Niittyviita, E.; Lassi, U.; Röning, J. Can interface insights for electric vehicle battery recycling. Batteries 2024, 10, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Zhang, B.; Lu, Y. Progress and perspective of high-voltage lithium cobalt oxide in lithium-ion batteries. J. Energy Chem. 2022, 74, 283–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Danilov, D.L.; Eichel, R.; Notten, P.H. A review of degradation mechanisms and recent achievements for Ni-rich cathode-based Li-ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2021, 11, 2103005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, T.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, X.; Shu, J.; Yue, C.; Zhou, A. A review of recent developments in the surface modification of LiMn2O4 as cathode material of power lithium-ion battery. Ionics 2009, 15, 779–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Huang, W.; Yang, L.; Pan, F. Structure and performance of the LiFePO4 cathode material: From the bulk to the surface. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 15036–15044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, A.; Kadam, S.; Li, H.; Shi, S.; Qi, Y. Review on modeling of the anode solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) for lithium-ion batteries. NPJ Comput. Mater. 2018, 4, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Yu, L.; Lou, X.W.D. Nanostructured conversion-type anode materials for advanced lithium-ion batteries. Chem 2018, 4, 972–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, C.; Du, J.; Zhang, X.; Chen, A.; Zhang, Q. Research progresses of liquid electrolytes in lithium-ion batteries. Small 2023, 19, 2205315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orendorff, C.J. The role of separators in lithium-ion cell safety. Electrochem. Soc. Interface 2012, 21, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltz, E.; Stroe, D.; Nørregaard, K.; Ingvardsen, L.S.; Christensen, A. Incremental capacity analysis applied on electric vehicles for battery state-of-health estimation. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2021, 57, 1810–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butera, A.; Gatteschi, V. EU Battery Regulation and the Role of Blockchain in Creating Digital Battery Passports. In Proceedings of the 2024 6th Conference on Blockchain Research & Applications for Innovative Networks and Services (BRAINS), Berlin, Germany, 9–11 October 2024; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Gianvincenzi, M.; Marconi, M.; Mosconi, E.M.; Tola, F. Toward a Resilient European Battery Ecosystem by 2030: Strategic Pathways to Meet EU Regulatory Targets. J. Energy Storage 2025, 132, 117851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohlmann, A.; Popowicz, M.; Schöggl, J.; Baumgartner, R.J. Digital product passports for electric vehicle batteries: Stakeholder requirements for sustainability and circularity. Clean. Prod. Lett. 2025, 8, 100090. [Google Scholar]

- Klohs, D.; Frieges, M.; Gorsch, J.; Ellmann, P.; Heimes, H.H.; Kampker, A. Product and Process Data Structure for Automated Battery Disassembly. Recycling 2025, 10, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, R. EU Battery Regulations: What do the New Rules Mean? 2024. Available online: http://journal.uptimeinstitute.com/eu-battery-regulations-what-do-the-new-rules-mean/ (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Ziva Buzeti, T.D.S. Digital Product Passports (DPPs) Required by EU Legislation Across Sectors: ESPR, Toys, Detergents, Batteries, and More. 2025. Available online: https://www.circularise.com/blogs/dpps-required-by-eu-legislation-across-sectors (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Gianvincenzi, M.; Marconi, M.; Mosconi, E.M.; Tola, F. A standardized data model for the battery passport: Paving the way for sustainable battery management. Procedia CIRP 2024, 122, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haupt, J.; Cerdas, F.; Herrmann, C. Derivation of requirements for life cycle assessment-related information to be integrated in digital battery passports. Procedia CIRP 2024, 122, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, J.; Schoeggl, J.; Baumgartner, R.J. End of life focused data model for a digital battery passport. Procedia CIRP 2024, 122, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühn, M.; Baumann, M.; Volz, F.; Stojanovic, L. Digital product passport design supporting the circular economy based on the asset administration shell. Sustainability 2025, 17, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosse, S.; Hagedorn, P.; Maibaum, J.; König, M. Digital twins for precast concrete: Advancing environmental analysis through integrated life cycle assessment. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computing in Civil and Building Engineering, Montreal, QC, Canada, 25–28 August 2024; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 613–627. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, M.; Meisen, T.; Plociennik, C.; Berg, H.; Pomp, A.; Windholz, W. Stop guessing in the dark: Identified requirements for digital product passport systems. Systems 2023, 11, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandini, G.; Buffi, A.; Caposciutti, G.; Marracci, M.; Tellini, B. An RFID System Enabling Battery Lifecycle Traceability. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for Automotive (MetroAutomotive), Modena, Italy, 28–30 June 2023; pp. 46–50. [Google Scholar]

- Scherr, F.; Basic, F.; Eder, P.; Steger, C.; Kofler, R. Next-Generation Battery Management Systems: Integrating RFID for Battery Passport Applications. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on RFID Technology and Applications (RFID-TA), Daytona Beach, FL, USA, 18–20 December 2024; pp. 137–140. [Google Scholar]

- Timms, P.D.; King, M.R.N. Complexity in the delivery of product passports: A system of systems approach to passport lifecycles. In Proceedings of the 2023 18th Annual System of Systems Engineering Conference (SoSe), Lille, France, 14–16 June 2023; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Rezaei, M.; Nekahi, A.; Feyzi, E.; MR, A.K.; Nanda, J.; Zaghib, K. Advancing the circular economy by driving sustainable urban mining of end-of-life batteries and technological advancements. Energy Storage Mater. 2025, 75, 104035. [Google Scholar]

- Basic, F.; Laube, C.R.; Stratznig, P.; Steger, C.; Kofler, R. Wireless BMS architecture for secure readout in vehicle and second life applications. In Proceedings of the 2023 8th International Conference on Smart and Sustainable Technologies (SpliTech), Split/Bol, Croatia, 20–23 June 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Beckers, C.; Hoedemaekers, E.; Dagkilic, A.; Bergveld, H.J. Round-trip energy efficiency and energy-efficiency fade estimation for battery passport. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Vehicle Power and Propulsion Conference (VPPC), Milan, Italy, 23–27 October 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Bockrath, S.; Pruckner, M. Generalized State of Health Estimation Approach based on Neural Networks for Various Lithium-Ion Battery Chemistries. In Proceedings of the 14th ACM International Conference on Future Energy Systems, Orlando, FL, USA, 20–23 June 2023; pp. 314–323. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L.; He, J. Battery passport collaborative development strategy: A cooperative-stochastic evolutionary game analysis. Energy 2025, 329, 136770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DIN DKE SPEC 99100:2025-02; Requirements for Data Attributes of the Battery Passport. DIN Media GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Wang, X.; Dai, H. Practical on-board measurement of lithium ion battery impedance based on distributed voltage and current sampling. Energies 2018, 11, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazali, A.K.; Aziz, N.A.A.; Hassan, M.K. Advanced algorithms in battery management systems for electric vehicles: A comprehensive review. Symmetry 2025, 17, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostenko, G.; Zaporozhets, A. Transition from electric vehicles to energy storage: Review on targeted lithium-ion battery diagnostics. Energies 2024, 17, 5132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GM Insights EV Battery Health Diagnostics System Market Report. 2024. Available online: https://www.gminsights.com/industry-analysis/ev-battery-health-diagnostics-system-market (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Department of the Treasury, Internal Revenue Service. Clean Vehicle Credits Under Sections 25E and 30D; Transfer of Credits; Critical Minerals and Battery Components; Foreign Entities of Concern. 2024. Available online: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2024/05/06/2024-09094/clean-vehicle-credits-under-sections-25e-and-30d-transfer-of-credits-critical-minerals-and-battery (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Department of the Treasury and the Internal Revenue Service. Treasury, IRS Provide Guidance for Those Who Manufacture New Clean Vehicles. 2023. Available online: https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/treasury-irs-provide-guidance-for-those-who-manufacture-new-clean-vehicles (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Cheng, Y.; Hao, H.; Tao, S.; Zhou, Y. Traceability management strategy of the EV power battery based on the blockchain. Sci. Program. 2021, 2021, 5601833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodenough, J.B. How we made the Li-ion rechargeable battery. Nat. Electron. 2018, 1, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houache, M.S.; Yim, C.; Karkar, Z.; Abu-Lebdeh, Y. On the Current and Future Outlook of Battery Chemistries for Electric Vehicles—Mini Review. Batteries 2022, 8, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergori, E.; Mocera, F.; Somà, A. Battery modelling and simulation using a programmable testing equipment. Computers 2018, 7, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Li, M.; Abd El-Hady, D.; Alshitari, W.; Al-Bogami, A.S.; Lu, J.; Amine, K. Commercialization of lithium battery technologies for electric vehicles. Adv. Energy Mater. 2019, 9, 1900161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauger, A.; Julien, C.M. Critical review on lithium-ion batteries: Are they safe? Sustainable? Ionics 2017, 23, 1933–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargos, P.H.; dos Santos, P.H.; dos Santos, I.R.; Ribeiro, G.S.; Caetano, R.E. Perspectives on Li-ion battery categories for electric vehicle applications: A review of state of the art. Int. J. Energy Res. 2022, 46, 19258–19268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. Global EV Outlook 2023. 2023. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2023 (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Liu, Q.; Su, X.; Lei, D.; Qin, Y.; Wen, J.; Guo, F.; Wu, Y.A.; Rong, Y.; Kou, R.; Xiao, X. Approaching the capacity limit of lithium cobalt oxide in lithium ion batteries via lanthanum and aluminium doping. Nat. Energy 2018, 3, 936–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.; Wu, X.; Wang, K.; Feng, Z.; Cheng, T.; Liu, Y.; Wang, M.; Chen, R.; Xu, L.; Zhou, J. An overview on the advances of LiCoO2 cathodes for lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2021, 11, 2000982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Xue, Z.; Yang, L.; Wang, J.; Meng, F.; Li, Q.; Pan, H.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, Z. An in situ formed surface coating layer enabling LiCoO2 with stable 4.6 V high-voltage cycle performances. Adv. Energy Mater. 2020, 10, 2001413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalluri, S.; Yoon, M.; Jo, M.; Park, S.; Myeong, S.; Kim, J.; Dou, S.X.; Guo, Z.; Cho, J. Surface Engineering Strategies of Layered LiCoO2 Cathode Material to Realize High-Energy and High-Voltage Li-Ion Cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 2017, 7, 1601507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, Q.; Ouyang, C.; Yu, X.; Ge, M.; Huang, X.; Hu, E.; Ma, C.; Li, S.; Xiao, R. Trace doping of multiple elements enables stable battery cycling of LiCoO2 at 4.6 V. Nat. Energy 2019, 4, 594–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Li, Y.; Yang, K.; Chen, Z.; Liu, J.; Qi, R.; Li, Z.; Zuo, C.; Zhao, W.; Yang, N. Interplay between multiple doping elements in high-voltage LiCoO2. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 5702–5710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Lee, S.; Manthiram, A. High-nickel NMA: A cobalt-free alternative to NMC and NCA cathodes for lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 2002718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, S.; Kinoshita, M.; Hosokawa, T.; Morigaki, K.; Nakura, K. Capacity fading of LiAlyNi1−x−yCoxO2 cathode for lithium-ion batteries during accelerated calendar and cycle life tests (effect of depth of discharge in charge–discharge cycling on the suppression of the micro-crack generation of LiAlyNi1−x−yCoxO2 particle). J. Power Sources 2014, 260, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostecki, R.; McLarnon, F. Local-Probe Studies of Degradation of Composite LiNi0.8Co0.15Al0.05O2 Cathodes in High-Power Lithium-Ion Cells. Electrochem. Solid-State Lett. 2004, 7, A380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.; Stach, E.A. Using in situ and operando methods to characterize phase changes in charged lithium nickel cobalt aluminum oxide cathode materials. J. Phys. D 2020, 53, 113002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, M.; Belharouak, I.; Zheng, J.; Wu, H.; Xiao, J.; Genc, A.; Amine, K.; Thevuthasan, S.; Baer, D.R.; Zhang, J. Formation of the spinel phase in the layered composite cathode used in Li-ion batteries. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 760–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Huang, R.; Makimura, Y.; Ukyo, Y.; Fisher, C.A.; Hirayama, T.; Ikuhara, Y. Microstructural changes in LiNi0. 8Co0. 15Al0. 05O2 positive electrode material during the first cycle. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2011, 158, A357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Ma, H.; Cha, H.; Lee, H.; Sung, J.; Seo, M.; Oh, P.; Park, M.; Cho, J. A highly stabilized nickel-rich cathode material by nanoscale epitaxy control for high-energy lithium-ion batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 2018, 11, 1449–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julien, C.M.; Mauger, A.; Groult, H.; Zaghib, K. Surface modification of positive electrode materials for lithium-ion batteries. Thin Solid Film. 2014, 572, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julien, C.M.; Mauger, A. NCA, NCM811, and the route to Ni-richer lithium-ion batteries. Energies 2020, 13, 6363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.; Chan, K.H.; Azimi, G. Review on the synthesis of LiNixMnyCo1−x−yO2 (NMC) cathodes for lithium-ion batteries. Mater. Today Energy 2022, 28, 101066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Zheng, J.; Wang, C.; Gu, M. Designing principle for Ni-rich cathode materials with high energy density for practical applications. Nano Energy 2018, 49, 434–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdock, B.E.; Toghill, K.E.; Tapia-Ruiz, N. A perspective on the sustainability of cathode materials used in lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2021, 11, 2102028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshetu, G.G.; Zhang, H.; Judez, X.; Adenusi, H.; Armand, M.; Passerini, S.; Figgemeier, E. Production of high-energy Li-ion batteries comprising silicon-containing anodes and insertion-type cathodes. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Cano, Z.P.; Yu, A.; Lu, J.; Chen, Z. Automotive Li-ion batteries: Current status and future perspectives. Electrochem. Energy Rev. 2019, 2, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, P.; Zhang, H.; Zi, Z.; Zhang, L.; Xu, X. Core–shell and concentration-gradient cathodes prepared via co-precipitation reaction for advanced lithium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 4254–4279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarascon, J.M. The Li-ion battery: 25 years of exciting and enriching experiences. Electrochem. Soc. Interface 2016, 25, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.; Hynan, P.; Von Jouanne, A.; Yokochi, A. Current Li-ion battery technologies in electric vehicles and opportunities for advancements. Energies 2019, 12, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Lee, S.; Oh, P.; Kim, Y.; Cho, J. High performance LiMn2O4 cathode materials grown with epitaxial layered nanostructure for Li-ion batteries. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 993–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erabhoina, H.; Thelakkat, M. Tuning of composition and morphology of LiFePO4 cathode for applications in all solid-state lithium metal batteries. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 5454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selinis, P.; Farmakis, F. A review on the anode and cathode materials for lithium-ion batteries with improved subzero temperature performance. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2022, 169, 010526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, M.U.; Chakraborty, S.; Akboy, E.; Sangwongwanich, A.; Stroe, D.I.; Hegazy, O.; Blaabjerg, F. Charging Strategies Influence on DC-DC Converter and Li-Ion Battery Performance. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE), Phoenix, AZ, USA, 20–24 October 2024; pp. 2248–2253. [Google Scholar]

- Tahir, M.U.; Sangwongwanich, A.; Stroe, D.; Blaabjerg, F. Optimized Multi-Stage Constant Current Charging Strategy for Li-ion Batteries. In Proceedings of the 2023 25th European Conference on Power Electronics and Applications (EPE’23 ECCE Europe), Aalborg, Denmark, 4–8 September 2023; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, S.; Bloking, J.T.; Chiang, Y. Electronically conductive phospho-olivines as lithium storage electrodes. Nat. Mater. 2002, 1, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Banis, M.N.; Xiao, B.; Lushington, A.; Xiao, W.; Li, R.; Sham, T.; Liang, G. Formation of size-dependent and conductive phase on lithium iron phosphate during carbon coating. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, C.; Yang, X.; Jiang, Q. Effects of carbon coating and metal ions doping on low temperature electrochemical properties of LiFePO4 cathode material. Electrochim. Acta 2012, 83, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; He, Y.; Gao, H.; Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Xu, H.; Wang, L.; He, X. Unraveling the doping mechanisms in lithium iron phosphate. Energy Mater. 2022, 2, 200013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Hwang, I.; Chang, D.; Park, K.; Kim, S.J.; Seong, W.M.; Eum, D.; Park, J.; Kim, B.; Kim, J. Nanoscale phenomena in lithium-ion batteries. Chem. Rev. 2019, 120, 6684–6737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahir, M.U.; Sangwongwanich, A.; Stroe, D.; Blaabjerg, F. Multi-objective optimization for multi-stage constant current charging for Li-ion batteries. J. Energy Storage 2024, 86, 111313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Shapter, J.G.; Li, Y.; Gao, G. Recent progress of advanced anode materials of lithium-ion batteries. J. Energy Chem. 2021, 57, 451–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, P.; Srivastava, S.K. Nanostructured anode materials for lithium ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 2454–2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Kersey-Bronec, F.E.; Ke, J.; Cloud, J.E.; Wang, Y.; Ngo, C.; Pylypenko, S.; Yang, Y. Study of lithium silicide nanoparticles as anode materials for advanced lithium ion batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 16071–16080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzereogu, P.U.; Omah, A.D.; Ezema, F.I.; Iwuoha, E.I.; Nwanya, A.C. Anode materials for lithium-ion batteries: A review. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 2022, 9, 100233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wu, X.; Chang, B.; Wang, K. Recent progress on germanium-based anodes for lithium ion batteries: Efficient lithiation strategies and mechanisms. Energy Storage Mater. 2020, 30, 146–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodlaki, D.; Yamamoto, H.; Waldeck, D.H.; Borguet, E. Ambient stability of chemically passivated germanium interfaces. Surf. Sci. 2003, 543, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Cho, Y.; Kim, K.; Kim, J.; Liu, M.; Cho, J. Germanium nanotubes prepared by using the kirkendall effect as anodes for high-rate lithium batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 9647–9650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Jo, C.; Kim, M.G.; Chun, J.; Lim, E.; Kim, S.; Jeong, S.; Kim, Y.; Lee, J. Mesoporous Ge/GeO2/carbon lithium-ion battery anodes with high capacity and high reversibility. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 5299–5309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Li, N.; Cui, H.; Wang, C. Embedded into graphene Ge nanoparticles highly dispersed on vertically aligned graphene with excellent electrochemical performance for lithium storage. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 19397–19404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Hwang, J.; Belharouak, I.; Sun, Y. Superior Li/Na-storage capability of a carbon-free hierarchical CoSx hollow nanostructure. Nano Energy 2017, 32, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.; Sun, Y.; Myung, S. Carbothermal synthesis of molybdenum(IV) oxide as a high rate anode for rechargeable lithium batteries. J. Power Sources 2015, 280, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Bai, Z.; Qian, Y.; Yang, J. Double-Walled Sb@ TiO2−x Nanotubes as a Superior High-Rate and Ultralong-Lifespan Anode Material for Na-Ion and Li-Ion Batteries. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 4126–4133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, K.; Lim, H.; Sun, Y.; Suh, K. α-Fe2O3 submicron spheres with hollow and macroporous structures as high-performance anode materials for lithium ion batteries. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 2897–2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Wang, Y.; Xia, Y. Ti-based compounds as anode materials for Li-ion batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 6652–6667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danquah, S.A.; Strimaitis, J.; Denize, C.F.; Pradhan, S.K.; Bahoura, M. LLCZN/PEO/LiPF6 composite solid-state electrolyte for safe energy storage application. Batteries 2022, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebert, F.; Longhini, M.; Conti, F.; Naylor, A.J. An electrochemical evaluation of state-of-the-art non-flammable liquid electrolytes for high-voltage lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2023, 556, 232412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Lai, J.; Kong, X.; Rajkovic, I.; Xiao, X.; Celik, H.; Yan, H.; Gong, H.; Rudnicki, P.E.; Lin, Y. A solvent-anchored non-flammable electrolyte. Matter 2023, 6, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, K.; Watanabe, M.; Lopes, J.N.C.; de Freitas, A.A. The heterogeneous nature of the lithium-ion diffusion in highly concentrated sulfolane-based liquid electrolytes. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 382, 121983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Lv, S.; Jiang, K.; Zhou, G.; Liu, X. Recent development of ionic liquid-based electrolytes in lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2022, 542, 231792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Zhao, J.; Liu, G.; Yu, W.; Dong, X.; Wang, J. Review on composite solid electrolytes for solid-state lithium-ion batteries. Mater. Today Sustain. 2023, 21, 100316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahniyaz, A.; de Meatza, I.; Kvasha, A.; Garcia-Calvo, O.; Ahmed, I.; Sgroi, M.F.; Giuliano, M.; Dotoli, M.; Dumitrescu, M.; Jahn, M.; et al. Progress in solid-state high voltage lithium-ion battery electrolytes. Adv. Appl. Energy 2021, 4, 100070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Sarkar, S.; Palakkathodi Kammampata, S.; Zhou, C.; Thangadurai, V. Li-stuffed garnet electrolytes: Structure, ionic conductivity, chemical stability, interface, and applications. Can. J. Chem. 2022, 100, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarma, P.V.; Cherusseri, J.; Varma, S.J. Polymer Nanocomposite-Based Solid Electrolytes for Lithium-Ion Batteries. In Polymer Electrolytes for Energy Storage Devices; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021; pp. 81–110. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, T.; Cheng, H.; Liu, Y.; Sun, Q.; Nie, W.; Lu, X.; Dong, P.; Song, M. A multifunctional Janus layer for LLZTO/PEO composite electrolyte with enhanced interfacial stability in solid-state lithium metal batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 2024, 65, 103091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, P.; Gao, Z.; Li, X.; Cui, W.; Li, R.; Ramakrishna, S.; Zhang, J.; Long, Y. Review on electrospinning anode and separators for lithium ion batteries. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 189, 113939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Gu, J.; Pan, C.; Zhang, J.; Wei, Z.; Zhao, Y. Recent developments of composite separators based on high-performance fibers for lithium batteries. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2022, 162, 107132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, B.; Li, X. Towards separator safety of lithium-ion batteries: A review. Mater. Chem. Front. 2024, 8, 309–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Q.; Tan, Z. A review of electrospun nanofiber-based separators for rechargeable lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2019, 443, 227262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Wang, F.; Wang, H.; Li, H.; Fan, Y.; Chan, D.; Chen, S.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Thermal-Stable Separators: Design Principles and Strategies Towards Safe Lithium-Ion Battery Operations. ChemSusChem 2022, 15, e202201464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Yang, R.; Wang, Y.; Fu, D.; Sheng, J.; Guo, X. A bacterial cellulose-based separator with tunable pore size for lithium-ion batteries. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 304, 120489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toquet, F.; Guy, L.; Schlegel, B.; Cassagnau, P.; Fulchiron, R. Combined roles of precipitated silica and porosity on electrical properties of battery separators. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2019, 223, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horváth, D.V.; Tian, R.; Gabbett, C.; Nicolosi, V.; Coleman, J.N. Quantifying the Effect of Separator Thickness on Rate Performance in Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2022, 169, 030503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poorshakoor, E.; Darab, M. Advancements in the development of nanomaterials for lithium-ion batteries: A scientometric review. J. Energy Storage 2024, 75, 109638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoodabadi, A.; Jin, C.; Wood III, D.L.; Singler, T.J.; Li, J. On electrolyte wetting through lithium-ion battery separators. Extrem. Mech. Lett. 2020, 40, 100960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.S. A review on the separators of liquid electrolyte Li-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2007, 164, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes-Pereira, J.; Costa, C.M.; Leones, R.; Silva, M.M.; Lanceros-Méndez, S. Li-ion battery separator membranes based on poly(vinylidene fluoride-trifluoroethylene)/carbon nanotube composites. Solid State Ion. 2013, 249–250, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Zhang, H.; Qin, G.; Li, Z.; Li, L.; Hong, H. A macro-porous graphene oxide-based membrane as a separator with enhanced thermal stability for high-safety lithium-ion batteries. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 22112–22120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Kelarakis, A.; Lin, Y.; Kang, C.; Yang, M.; Cheng, C.; Wang, Y.; Giannelis, E.P.; Tsai, L. Nanoparticle-coated separators for lithium-ion batteries with advanced electrochemical performance. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011, 13, 14457–14461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inaguma, Y.; Nakashima, M. A rechargeable lithium–air battery using a lithium ion-conducting lanthanum lithium titanate ceramics as an electrolyte separator. J. Power Sources 2013, 228, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, L.; Wang, F.; Qin, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, N.; Liu, X.; Chen, G. Anionic metal-organic framework modified separator boosting efficient Li-ion transport. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 451, 138536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozali Balkanloo, P.; Poursattar Marjani, A.; Zanbili, F.; Mahmoudian, M. Clay mineral/polymer composite: Characteristics, synthesis, and application in Li-ion batteries: A review. Appl. Clay Sci. 2022, 228, 106632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, P.P.; McShane, E.J.; Colclasure, A.M.; Balsara, N.; Brown, D.E.; Cao, C.; Chen, B.; Chinnam, P.R.; Cui, Y.; Dufek, E.J. A review of existing and emerging methods for lithium detection and characterization in Li-ion and Li-metal batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2021, 11, 2100372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Han, Y.; Fraggedakis, D.; Das, S.; Zhou, T.; Yeh, C.; Xu, S.; Chueh, W.C.; Li, J.; Bazant, M.Z. Interplay of lithium intercalation and plating on a single graphite particle. Joule 2021, 5, 393–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duru, K.K.; Karra, C.; Venkatachalam, P.; Betha, S.A.; Madhavan, A.A.; Kalluri, S. Critical insights into fast charging techniques for lithium-ion batteries in electric vehicles. IEEE Trans. Device Mater. Reliab. 2021, 21, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Bai, Y.; Wu, C. Charactering and optimizing cathode electrolytes interface for advanced rechargeable batteries: Promises and challenges. Green Energy Environ. 2022, 7, 606–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wei, Z.; Knoll, A.C. Charging optimization for li-ion battery in electric vehicles: A review. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2021, 8, 3068–3089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scipioni, R.; Isheim, D.; Barnett, S.A. Revealing the complex layered-mosaic structure of the cathode electrolyte interphase in Li-ion batteries. Appl. Mater. Today 2020, 20, 100748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Qin, C.; Wang, K.; Han, X.; Li, J.; Sui, M.; Yan, P. Deciphering the critical effect of cathode-electrolyte interphase by revealing its dynamic evolution. J. Energy Chem. 2023, 81, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, T.; Kerekes, T.; Sera, D.; Stroe, D. Degradation behavior analysis of High Energy Hybrid Lithium-ion capacitors in stand-alone PV applications. In Proceedings of the IECON 2022–48th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Brussels, Belgium, 17–20 October 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, T.; Kerekes, T.; Sera, D.; Spataru, S.; Stroe, D. Sizing of Hybrid Supercapacitors for Off-Grid PV Applications. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE), Virtual, 10–14 October 2021; pp. 232–237. [Google Scholar]

- Lazanas, A.C.; Prodromidis, M.I. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy—A tutorial. ACS Meas. Sci. Au 2023, 3, 162–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, T.; Tahir, M.U.; Knap, V.; Stroe, D.I. Degradation Analysis of Lithium-ion Capacitors based on Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE), Phoenix, AZ, USA, 20–24 October 2024; pp. 559–564. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, W.; Peng, Y.; Wei, Y.; Yang, Y. Application of electrochemical impedance spectroscopy to degradation and aging research of lithium-ion batteries. J. Phys. Chem. C 2023, 127, 4465–4495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mc Carthy, K.; Gullapalli, H.; Ryan, K.M.; Kennedy, T. Use of impedance spectroscopy for the estimation of Li-ion battery state of charge, state of health and internal temperature. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2021, 168, 080517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Sundaresan, S.; Balasingam, B. Battery parameter analysis through electrochemical impedance spectroscopy at different state of charge levels. J. Low. Power Electron. Appl. 2023, 13, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Wang, D.; Wang, H. New method for acquisition of impedance spectra from charge/discharge curves of lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2022, 535, 231483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Kim, M.; Tsai, Y.; Zapol, P.; Trask, S.E.; Bloom, I. Extreme fast charging: Effect of positive electrode material on crosstalk. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2022, 169, 110505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habte, B.T.; Jiang, F. Microstructure reconstruction and impedance spectroscopy study of LiCoO2, LiMn2O4 and LiFePO4 Li-ion battery cathodes. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2018, 268, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfamhret, Y.; Liu, H.; Chai, Z.; Berg, E.; Younesi, R. On the manganese dissolution process from LiMn2O4 cathode materials. ChemElectroChem 2021, 8, 1516–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubal, J.J.; Knehr, K.W.; Susarla, N.; Tornheim, A.; Dunlop, A.R.; Dees, D.D.; Jansen, A.N.; Ahmed, S. The influence of temperature on area-specific impedance and capacity of Li-ion cells with nickel-containing positive electrodes. J. Power Sources 2022, 543, 231864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dose, W.M.; Temprano, I.; Allen, J.P.; Bjorklund, E.; O’Keefe, C.A.; Li, W.; Mehdi, B.L.; Weatherup, R.S.; De Volder, M.F.; Grey, C.P. Electrolyte reactivity at the charged Ni-rich cathode interface and degradation in Li-ion batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 13206–13222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IEC 62660-1:2018; Secondary Lithium-Ion Cells for the Propulsion of Electric Road Vehicles—Part 1: Performance Testing. International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC): Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- IEC 62660-2:2018; Secondary lithium-Ion Cells for the Propulsion of Electric Road Vehicles—Part 2: Reliability and Abuse Testing. International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC): Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- IEC 62660-3:2022; Secondary lithium-Ion Cells for the Propulsion of Electric Road Vehicles—Part 3: Safety Requirements. International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC): Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- Kasper, M.; Leike, A.; Al-Zubaidi R-Smith, N.; Papachristou, A.; Kienberger, F. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy Accuracy and Repeatability Analysis of 10 kWh Automotive Battery Module. Batteries 2025, 11, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). Battery_Data_Tools (Computer Software). GitHub. 2025. Available online: https://github.com/NREL/battery_data_tools (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Paulson, N.; Ward, L.; Kubal, J.; Blaiszik, B. Battery-Data-Toolkit (Computer Software). GitHub. 2021. Available online: https://github.com/materials-data-facility/battery-data-toolkit (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- EUR 29371 EN; Standards for the Performance and Durability Assessment of Electric Vehicle Batteries. Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018. Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC113420 (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Crescentini, M.; De Angelis, A.; Ramilli, R.; De Angelis, G.; Tartagni, M.; Moschitta, A.; Traverso, P.A.; Carbone, P. Online EIS and diagnostics on lithium-ion batteries by means of low-power integrated sensing and parametric modeling. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2020, 70, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Balasingam, B. A Comparison of Battery Equivalent Circuit Model Parameter Extraction Approaches Based on Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy. Batteries 2024, 10, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoshima, T.; Mukoyama, D.; Nakazawa, K.; Gima, Y.; Isawa, H.; Nara, H.; Momma, T.; Osaka, T. Application of Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy to Ferri/Ferrocyanide Redox Couple and Lithium Ion Battery Systems Using a Square Wave as Signal Input. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 180, 922–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sihvo, J.; Roinila, T.; Stroe, D. Cell-Level Implementation of Current-Sensorless On-Board Impedance Measurements in Multi-Cell Lithium-Ion Battery Stacks. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2025, 61, 4226–4233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Peng, J.; Cai, L.; Song, Z. Rapid impedance extraction for lithium-ion battery by integrating power spectrum and frequency property. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2023, 71, 7220–7229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, A.; Schoukens, J.; Godfrey, K.R.; Carbone, P. Practical issues in the synthesis of ternary sequences. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2016, 66, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sihvo, J.; Hallemans, N.; Tan, A.H.; Howey, D.A.; Duncan, S.; Roinila, T. Pseudo-random sequences for low-cost operando impedance measurements of Li-ion batteries. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.07519. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Lu, Z. A robust algorithm for state-of-charge estimation under model uncertainty and voltage sensor bias. Energies 2022, 15, 1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Fu, R. Stability Analysis of EKF-Based SOC Observer for Lithium-Ion Battery. Energies 2023, 16, 5946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Ji, G.; Liu, Z. Design and experiment of nonlinear observer with adaptive gains for battery state of charge estimation. Energies 2017, 10, 2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Gabalawy, M.; Mahmoud, K.; Darwish, M.M.; Dawson, J.A.; Lehtonen, M.; Hosny, N.S. Reliable and robust observer for simultaneously estimating state-of-charge and state-of-health of lifepo4 batteries. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Wang, S.; Fernandez, C.; Yu, C.; Fan, Y.; Cao, W. Novel reduced-order modeling method combined with three-particle nonlinear transform unscented Kalman filtering for the battery state-of-charge estimation. J. Power Electron. 2020, 20, 1541–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plank, C.; Rüther, T.; Jahn, L.; Schamel, M.; Schmidt, J.P.; Ciucci, F.; Danzer, M.A. A review on the distribution of relaxation times analysis: A powerful tool for process identification of electrochemical systems. J. Power Sources 2024, 594, 233845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iurilli, P.; Brivio, C.; Carrillo, R.E.; Wood, V. EIS2MOD: A DRT-based modeling framework for li-ion cells. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2021, 58, 1429–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.K.; Hogue, J.D.; Sander, G.K.; Renaut, R.A.; Popat, S.C. Non-negatively constrained least squares and parameter choice by the residual periodogram for the inversion of electrochemical impedance spectroscopy data. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2015, 278, 52–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, P.; Yang, K.; Song, Z.; Pang, Z.; Feng, Z.; Meng, J. An efficient electrochemical optimizer for the distribution of relaxation times of lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2024, 605, 234489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maradesa, A.; Py, B.; Huang, J.; Lu, Y.; Iurilli, P.; Mrozinski, A.; Law, H.M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, J. Advancing electrochemical impedance analysis through innovations in the distribution of relaxation times method. Joule 2024, 8, 1958–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukamp, B.A. Fourier transform distribution function of relaxation times; application and limitations. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 154, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effat, M.B.; Ciucci, F. Bayesian and hierarchical Bayesian based regularization for deconvolving the distribution of relaxation times from electrochemical impedance spectroscopy data. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 247, 1117–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ciucci, F. The Gaussian process distribution of relaxation times: A machine learning tool for the analysis and prediction of electrochemical impedance spectroscopy data. Electrochim. Acta 2020, 331, 135316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Yang, L.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Meng, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, S.; Li, Y. SOH estimation method for lithium-ion batteries based on an improved equivalent circuit model via electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. J. Energy Storage 2024, 86, 111167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Hui, R.; Wang, B.; Zhang, J. A review of AC impedance modeling and validation in SOFC diagnosis. Electrochim. Acta 2007, 52, 8144–8164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iurilli, P.; Koch, N.; Carrillo, R.E.; Brivio, C. DRT-based SoC estimation for commercial Li-ion battery pack. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Clean Electrical Power (ICCEP), Sicily, Italy, 27–29 June 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, M.; Li, X.; Yang, Z.; Chang, Y.; Liu, W.; Luo, Y.; Lei, W.; Ren, M.; Zhang, C. State of health (SOH) assessment for LIBs based on characteristic electrochemical impedance. J. Power Sources 2024, 603, 234386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourelly, C.; Vitelli, M.; Milano, F.; Molinara, M.; Fontanella, F.; Ferrigno, L. Eis-based soc estimation: A novel measurement method for optimizing accuracy and measurement time. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 91472–91484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Zhang, L.; Wang, W.; Li, S.; Chen, S.; Yang, S.; Li, J.; Liu, X. State of charge estimation method by using a simplified electrochemical model in deep learning framework for lithium-ion batteries. Energy 2023, 278, 127846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebhart, B.; Komsiyska, L.; Endisch, C. Passive impedance spectroscopy for monitoring lithium-ion battery cells during vehicle operation. J. Power Sources 2020, 449, 227297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Wang, D.; Yu, B.; Wang, F.; Chen, S.; Sun, X.; Dong, H. Research on online passive electrochemical impedance spectroscopy and its outlook in battery management. Appl. Energy 2024, 363, 123046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaresan, S.; Pattipati, K.; Balasingam, B. Fast Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy for Battery Testing. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 34th International Symposium on Industrial Electronics (ISIE), Toronto, ON, Canada, 20–23 June 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.; Lai, Z.; Zhi, H.; Zou, Y.; Jin, Y.; Zeng, K. Automated workflow of EIS data validation and quality improvement based on the definition, detection, and removal of outliers. Electrochim. Acta 2023, 461, 142661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sockeel, N.; Ball, J.; Shahverdi, M.; Mazzola, M. Passive tracking of the electrochemical impedance of a hybrid electric vehicle battery and state of charge estimation through an extended and unscented Kalman filter. Batteries 2018, 4, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klotz, D.; Schönleber, M.; Schmidt, J.P.; Ivers-Tiffée, E. New approach for the calculation of impedance spectra out of time domain data. Electrochim. Acta 2011, 56, 8763–8769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, T.M.S. CellPassport: Cloud-Based EIS Battery Diagnostic System for Predictive Battery Cell State and Smart Energy Management Integration. 2025. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Tarek-Ibrahim-31/publication/390743440_CellPassport_Cloud-based_EIS_battery_diagnostic_system_for_Predictive_Battery_cell_state_and_Smart_Energy_management_Integration/links/67fbcc71bd3f1930dd5d6298/CellPassport-Cloud-based-EIS-battery-diagnostic-system-for-Predictive-Battery-cell-state-and-Smart-Energy-management-Integration.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Gasper, P.; Schiek, A.; Smith, K.; Shimonishi, Y.; Yoshida, S. Predicting battery capacity from impedance at varying temperature and state of charge using machine learning. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2022, 3, 101184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Tseng, K.J. Holistic data-driven method for optimal sizing and operation of an urban islanded microgrid. Energy Convers. Econ. 2021, 2, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zheng, Z.; Büyüktahtakın, İ.E.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, P. Battery asset management with cycle life prognosis. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2021, 216, 107948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severson, K.A.; Attia, P.M.; Jin, N.; Perkins, N.; Jiang, B.; Yang, Z.; Chen, M.H.; Aykol, M.; Herring, P.K.; Fraggedakis, D. Data-driven prediction of battery cycle life before capacity degradation. Nat. Energy 2019, 4, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, P.M.; Grover, A.; Jin, N.; Severson, K.A.; Markov, T.M.; Liao, Y.; Chen, M.H.; Cheong, B.; Perkins, N.; Yang, Z. Closed-loop optimization of fast-charging protocols for batteries with machine learning. Nature 2020, 578, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, L.; Li, J.; Meng, L.; Zhu, L.; Shen, H.T. Transfer learning-based state of charge and state of health estimation for li-ion batteries: A review. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2023, 10, 1465–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Deng, Z.; Zhang, X.; Bao, H.; Cheng, D. Battery state of health estimation across electrochemistry and working conditions based on domain adaptation. Energy 2024, 297, 131294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, G.; Gao, G.; Lou, Y.; Yu, J.; Chen, C.; Wei, J. Hybrid physics and data-driven electrochemical states estimation for lithium-ion batteries. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2024, 39, 2689–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.; Kim, J.; Moon, I. Hybrid data-driven deep learning model for state of charge estimation of Li-ion battery in an electric vehicle. J. Energy Storage 2024, 97, 112887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navidi, S.; Thelen, A.; Li, T.; Hu, C. Physics-informed machine learning for battery degradation diagnostics: A comparison of state-of-the-art methods. Energy Storage Mater. 2024, 68, 103343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Lü, Z.; Lin, W.; Li, J.; Pan, H. A new state-of-health estimation method for lithium-ion batteries through the intrinsic relationship between ohmic internal resistance and capacity. Measurement 2018, 116, 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.-F.; Dung, L.-R. Offline State-of-Health Estimation for High-Power Lithium-Ion Batteries Using Three-Point Impedance Extraction Method. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2017, 66, 2019–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Pan, Z.; Han, X.; Lu, L.; Ouyang, M. An easy-to-implement multi-point impedance technique for monitoring aging of lithium ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2019, 417, 188–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wei, X.; Dai, H. Estimation of state of health of lithium-ion batteries based on charge transfer resistance considering different temperature and state of charge. J. Energy Storage 2019, 21, 618–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingant, R.; Bernard, J.; Moynot, V.S.; Delaille, A.; Mailley, S.; Hognon, J.; Huet, F. EIS measurements for determining the SOC and SOH of Li-ion batteries. ECS Trans. 2011, 33, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Li, S.; Jin, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, H. Single Frequency Feature Point Derived from DRT for SOH Estimation of Lithium Ion Battery. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2025, 172, 030514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Z.; Yang, K.; Song, Z.; Niu, P.; Chen, G.; Meng, J. A new method for determining SOH of lithium batteries using the real-part ratio of EIS specific frequency impedance. J. Energy Storage 2023, 72, 108693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezpeleta, I.; Fernández, J.; Giráldez, D.; Freire, L. Rapid and Non-Invasive SoH Estimation of Lithium-Ion Cells via Automated EIS and EEC Models. Batteries 2025, 11, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sihvo, J.; Roinila, T.; Stroe, D. SOH analysis of Li-ion battery based on ECM parameters and broadband impedance measurements. In Proceedings of the IECON 2020 the 46th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Singapore, 18–21 October 2020; pp. 1923–1928. [Google Scholar]

- ISO/SAE 21434:2021; Road Vehicles: Cybersecurity Engineering. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- IEC 62443; Industrial Communication Networks—Network and System Security. International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC): Geneva, Switzerland, 2010.

- Hasan, H.R.; Salah, K.; Mayyas, A.; Musamih, A.; Yaqoob, I.; Omar, M.; Jayaraman, R. Using composable NFTs and blockchain for the creation of EV battery digital passports with sustainability and traceability features. Sustain. Futures 2025, 10, 100847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, D.; Son, S.; Park, K.; Das, A.K.; Park, Y. Design of blockchain-based multi-domain authentication protocol for secure ev charging services in v2g environments. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 21783–21795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; He, H.; Wei, Z.; Zhao, P. Edge computing for vehicle battery management: Cloud-based online state estimation. J. Energy Storage 2022, 55, 105502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Song, H.; Kaiwartya, O.; Zhou, B.; Zhuang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, X. Mobile Edge Computing for Big-Data-Enabled Electric Vehicle Charging. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2018, 56, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, W.A.M. Digital Twin and Security Solutions for Intelligent Transportation Systems. Ph.D. Thesis, Politecnico di Milano, Milan, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M.; Kaddoum, G.; Li, W.; Yuen, C.; Tariq, M.; Poor, H.V. A smart digital twin enabled security framework for vehicle-to-grid cyber-physical systems. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2023, 18, 5258–5271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellare, M.; Tackmann, B. The multi-user security of authenticated encryption: AES-GCM in TLS 1.3. In Proceedings of the Annual International Cryptology Conference, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 14–18 August 2016; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 247–276. [Google Scholar]

- Crocetti, L.; Di Rienzo, R.; Verani, A.; Baronti, F.; Roncella, R.; Saletti, R. A novel and robust security approach for authentication, integrity, and confidentiality of Lithium-ion Battery Management Systems. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Industrial Electronics for Sustainable Energy Systems (IESES), Shanghai, China, 26–28 July 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- NIST SP 800-57; Recommendation for Key Management. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST): Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Grassi, P.A.; Garcia, M.E.; Fenton, J.L. Draft NIST Special Publication 800-63-3 Digital Identity Guidelines; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Los Altos, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Anbalagan, S.; Raja, G.; Gurumoorthy, S.; Suresh, R.D.; Dev, K. IIDS: Intelligent intrusion detection system for sustainable development in autonomous vehicles. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 15866–15875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Gholve, A.; Kotalwar, K. Automotive security solution using hardware security module (HSM). In Proceedings of the International Automotive CAE Conference—Road to Virtual World, Gurugram, India, 23–24 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Valentin Weber, M.P.R. Connected Vehicle Cyber Security: The EU Must Consider Nontechnical Risk Factors. 2025. Available online: https://dgap.org/en/research/publications/connected-vehicle-cybersecurity-eu-must-consider-non-technical-risk-factors (accessed on 20 November 2025).

| Symbol | Cathode | Anode | Chemical Reaction at Anode (Discharging) | Chemical Reaction at Cathode (Charging) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LCO | LiCoO2 | Graphite | ||

| NCA | LiNi1−x−yCoxAlyO2 | Graphite | ||

| NMC | LiNi1−x−yMnxCoyO2 | Graphite | ||

| LMO | LiMn2O4 | Graphite | ||

| LFP | LiFePO4 | Graphite |

| Cell Manufacturer | Cell Type | Cell Chemistry | Cell Voltage (V) | Cell Capacity (Ah) | Energy Density (WhKg−1) | Installed in | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cathode | Anode | Company | EV Model | |||||

| A123 | Pouch | LFP | C | 3.3 | 20 | 131 | Chevy | Spark |

| BYD | Prismatic | LFP | C | 3.2 | 216 | 166–140 | BYD | Tang electric |

| AESC | Pouch | NMC532 | C | 3.65 | 56.3 | 130 | Nissan | Leaf |

| AESC | Pouch | LMO-NCA | C | 3.75 | 33 | 155 | Nissan | Leaf |

| LG Chem | Pouch | NMC721 | C | 2.08 | 130 | 160 | Renault | Zoe |

| LG Chem | Pouch | NMC721 | C | 1.85 | 145 | 164 | Volkswagen | ID.3 |

| LG Chem | Pouch | LMO-NMC | C | 3.70 | 16 | - | Ford | Focus |

| LG Chem | Pouch | NMC721 | C | 3.65 | 64.6 | 263 | Audi | e-Tran GT |

| Samsung SDI | Prismatic | NMC111 | C | 3.7 | 37 | 185 | Volkswagen | e-Golf |

| Samsung SDI | Prismatic | NMC622 | C | 3.68 | 94 | 148 | BMW | i3 |

| Panasonic | Cylindrical | NCA | C | 3.6 | 3.4 | 236 | Tesla | Model S |

| Panasonic | Cylindrical | NCA | C or SiOC | 3.6 | 3.4 | 236 | Tesla | Model X |

| Panasonic | Cylindrical | NCA | C or SiOC | 3.6 | 4.75 | 260 | Tesla | Model 3 |

| Li-Energy Japan | Prismatic | LMO-NMC | C | 3.7 | 50 | 109 | Mitsubishi | i-MiEV |

| SK Innovation | Pouch | NMC811 | C | 3.56 | 180 | 250 | Kia | Niro |

| SK Innovation | Pouch | NMC811 | C | 3.56 | 180 | 250 | Kia | Soul |

| Nanomaterial | Material Production Companies | Material Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | BYK Additives, Cabot Corporation, Arkema, Nanocyl, OCSiAl, LG Chem | Used to enhance the mechanical strength and electrical conductivity of separators. |

| Graphene and Graphene Oxide | Graphenea, NanoXplore/XG Sciences | Incorporated to improve mechanical properties, thermal stability, and ion conductivity. |

| Nanofibers (Polymer, Ceramic, or Carbon) | Asahi Kasei, Hollingsworth and Vose | Electrospun nanofibers are used to create separator mats with increased porosity, improving electrolyte penetration. |

| silicon Dioxide (SiO2) | Cabot Corporation | Used to enhance the thermal stability of separators and improve their mechanical properties. |

| Lithium Titanate (Li4Ti5O12) | NEI Corporation, Umicore | Used to improve ion conductivity and thermal stability. |

| Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | BASF | Used for their porosity to enhance electrolyte penetration and ion transport. |

| Polymer Nanocomposites | LG Chem, Arkema | Nanoscale additives are incorporated into polymer separators to improve their overall mechanical properties. |

| Parameter | Diagnostic Use | Minimum Metadata Required | Standardization Gaps |

|---|---|---|---|

| RΩ | Ohmic resistance of electrolyte and contacts | Fixture description, cable correction, geometry, T, SoC | Fixture-dependent corrections, non-uniform area normalization |

| Rct | Interfacial kinetics; sensitive to SEI/CEI, metal dissolution | ECM topology, frequency range, SoC, T, rest time | Variable ECM topologies and fitting ranges, SoC/T normalization lacking |

| CPE | Non-ideal double-layer capacitance in porous electrodes | Electrode area, porosity, conversion model | Non-uniform capacitance conversion |

| W | Solid-state or electrolyte diffusion limitation/linked to mass transport | Model type, fit range, electrode thickness | Finite vs. semi-infinite definitions and mixed units |

| Ref. | Battery Chemistry | Part of Impedance | Frequency Range | Used Model for SOH Estimation | SoH Estimation Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [204] | NMC | RΩ | - | RLS | 4% |

| [205] | LFP | Rct | - | TPE | 6.1% |

| [206] | NMC | RΩ, Rct and RSEI | Determine via TC | DRT | <10% |

| [184] | NCR and LFP | RΩ, Rct and RSEI | 20 Hz–1 kHz | DRT | <3% |

| [207] | LFP | Rct | 0.01 Hz–1 kHz | CPSA/GA | <15% |

| [208] | LFP, LTO | RΩ, Rct and CPE, W | 0.01–100 kHz | LS/PF/LR | 7% |

| [209] | LCO | RΩ, Rct RSEI, CSEI CPE, W | 0.02 Hz–20 kHz | DRT/LSTM | 2.68% |

| [210] | LFP | Zreal | 0.1 Hz–10 kHz | RPR | 4.46% |

| [181] | LCO | RΩ, Rct RSEI, CSEI CPE, W | 0.02 Hz–20 KHz | GPR | 2.95% |

| [211] | NMC | RΩ, Rct, CPEs | 0.01 Hz–10 kHz | Empirical | 5% |

| [187] | NMC | Zreal | 25 kHz | SASA | 2.3% |

| [212] | NMC | RΩ, Rct RSEI | 180 mHz–2.7 kHz | Empirical | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tahir, M.U.; Ibrahim, T.; Kerekes, T. Battery Passport and Online Diagnostics for Lithium-Ion Batteries: A Technical Review of Materials–Diagnostics Interactions and Online EIS. Batteries 2025, 11, 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries11120442

Tahir MU, Ibrahim T, Kerekes T. Battery Passport and Online Diagnostics for Lithium-Ion Batteries: A Technical Review of Materials–Diagnostics Interactions and Online EIS. Batteries. 2025; 11(12):442. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries11120442

Chicago/Turabian StyleTahir, Muhammad Usman, Tarek Ibrahim, and Tamas Kerekes. 2025. "Battery Passport and Online Diagnostics for Lithium-Ion Batteries: A Technical Review of Materials–Diagnostics Interactions and Online EIS" Batteries 11, no. 12: 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries11120442

APA StyleTahir, M. U., Ibrahim, T., & Kerekes, T. (2025). Battery Passport and Online Diagnostics for Lithium-Ion Batteries: A Technical Review of Materials–Diagnostics Interactions and Online EIS. Batteries, 11(12), 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries11120442