Abstract

It is well known that high ethanol levels in wines adversely affect the perception of new wine consumers. Moreover, numerous issues, such as civil restrictions, health risk and trade barriers, are associated with high ethanol concentrations. Several strategies have been proposed to produce wines with lower alcoholic content, one simple and inexpensive approach being the use of new wine native yeasts with less efficiency in sugar to ethanol conversion. Nevertheless, it is also necessary that these yeasts do not impair the quality of wine. In this work, we tested the effect of sequential culture between Hanseniaspora uvarum BHu9 and Saccharomyces cerevisiae BSc114 on ethanol production. Then, the wines produced were analyzed by GC-MS and tested by a sensorial panel. Co-culture had a positive impact on ethanol reduction and sensory profile when compared to the S. cerevisiae monoculture. Wines with lower alcohol content were related to fruity aroma; moreover, color intensity was associated. The wines obtained with S. cerevisiae BSc114 in pure conditions were described by parameters linked with high ethanol levels, such as hotness and astringency. Moreover, floral profile was related to this treatment. Based on these findings, this work provides a contribution to answer the current consumers’ preferences and addresses the main challenges faced by the enological industry.

1. Introduction

Well-structured and full-body wines have become the preferences of many new wine consumers. In order to obtain these characteristics, it is necessary to ensure optimal phenolic maturity of grapes, which requires longer grape ripening times [1]. However, in the context of global warming, this practice results in a significant increase in the berry sugar content at the moment of harvesting, and consequently higher alcohol levels in the wine [2]. Numerous issues are associated with high ethanol levels in wine such as consumers’ rejection, civil restrictions, health risk, and trade barriers [1,3,4]. The sensorial quality of wines is also significantly affected because of an increase in the perception of bitterness, sweetness, astringency and hotness, and masking of volatile aromatic compounds [5,6]. In this context, different technological solutions have been evaluated: harvest of unripe berries, increase in crop load, shading bunches, choosing proper irrigation techniques, and modulation of source–sink relationships by removing leaves or topping shoots [7,8,9,10]. Other authors have tried partial dealcoholization with physical methods [11,12,13].

More recently, microbiological solutions have been proposed by using selected non-Saccharomyces and Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast strains in simultaneous or sequential fermentations [4,14,15,16]. The use of non-Saccharomyces yeasts has become a common trend in the main wine regions, particularly because of their effects on the composition, flavor and color of the wine [17,18]. In addition to the aforementioned effects, this yeast group is also known to be less efficient in the production of ethanol from consumed sugars when compared with S. cerevisiae yeasts [19].

Hanseniaspora genera as a whole and particularly Hanseniaspora uvarum species are non-Saccharomyces yeasts commonly encountered at high concentrations on the grape surface and throughout the fermentation process [20]. Recently, 28 H. uvarum isolates were evaluated by our research group and they demonstrated interesting enological characteristics such us: ability to grow at high sugar, ethanol and SO2 contents; to produce high concentrations of glycerol; low acetic acid and hydrogen sulfide levels; and the release of proteolytic enzymes [21]. Moreover, it is important to highlight that H. uvarum was also found to be a potential candidate to produce less ethanol because it requires more than 19 g/L of consumed sugar to produce 1% v/v of ethanol [21]. In a more recent study, a selected H. uvarum yeast strain was assessed in sequential inoculations with S. cerevisiae yeasts under optimized fermentation conditions [22]. The authors found that the ethanol levels were significantly reduced compared with fermentations carried out with S. cerevisiae monocultures. Nevertheless, and in order to achieve holistic knowledge, the aim of the present work was to assess the aromatic impact of an optimized inoculum of H. uvarum/S. cerevisiae yeasts in fresh must and compare the findings with a S. cerevisiae monoculture. It is also relevant to establish how ethanol reduction affects sensorial perception. The results would allow the design of a comprehensive microbiological strategy in order to answer the current consumers’ preferences and address the main challenges faced by the enological industry.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microorganisms

Hanseniaspora uvarum BHu9 and Saccharomyces cerevisiae BSc114 were used in the present study. Both strains of yeasts were previously selected based on their oxidative and fermentative metabolism in order to obtain reduced ethanol wines [21]. Strains were obtained from the Culture Collection of Autochthonous Microorganisms (Institute of Biotechnology, School of Engineering—UNSJ, San Juan, Argentina) and preserved at −80 °C until use.

2.2. Yeast Inoculum Preparation

Each strain was grown on YEPD agar for 48 h and the biomasses were transferred to YEPD broth (130 rpm during 4 h) [22]. Then, strains were transferred to grape must (13° Brix, pH 3.8) supplemented with 0.1% yeast extract and 0.4% peptone, and incubated at 25 °C during 24 h under aerobic conditions (130 rpm). YEPD broth was used for pre-adaptation in order to reduce the lag-stage in the grape must, which allows strains to grow immediately exponentially in the grape juice [22]. Once the pre-adaptation process had finished, cells were counted with an improved Neubauer chamber.

2.3. Grapes and Vineyard Location

All experiments were carried out using Vitis vinifera L. cv. Malbec grapes harvested during the 2017 vintage from a vineyard located in Cañada Honda, San Juan, Argentina (31°58′34″S 68°32′52″W) at 610 m altitude. Grapes were manually destemmed and mixed to obtain a homogeneous solution. The composition of the fresh juice was as follows: sugar (glucose and fructose), 238.2 g/L; pH, 3.8; titratable acidity, 5.3 g/L; and yeast assimilable nitrogen (YAN), 175 mg/L. Then, 5-L vessels equipped with a Muller valve were filled with juice (3 L) and supplemented with 50 ppm of free SO2 before fermentation. The Muller valve was filled with a solution of 50% sulfuric acid and 50% sterile water distilled. Vinifications were performed in triplicate.

2.4. Inoculation and Winemaking

Lab-scale fermentations were conducted under optimized factors previously determined by Maturano et al. [22]. Treatment 1 (T1): H. uvarum BHu9 was inoculated (T0) at a concentration of 5 × 106 cells/mL, and 48 h later, 2 × 106 cells/mL of S. cerevisiae BSc114 were sequentially inoculated. In parallel, a single culture of 2 × 106 cells/mL of S. cerevisiae yeasts was inoculated at T0 as control treatment (TC). Both fermentations were performed at 25 ± 1 °C under static conditions. Musts were supplemented with nitrogen by adding 20 mg/L of (NH4)2HPO4 twice: after 48 h and in the middle of the fermentation (when 5% weight loss was verified). Nitrogen supplement was established based on nitrogen uptake previously determined with selected yeasts (data not shown). Punch down was carried out every 24 h in order to keep acceptable dissolved oxygen levels throughout the process. The fermentation progress was evaluated by the weight loss caused by CO2 production and vessels were weighed every 24 h.

Samples were collected periodically and viable cell counts were determined by plating onto Wallerstein Laboratory Nutrient (WLN) Agar medium (Oxoid, Hampshire, UK). Dilutions of 10−3, 10−4 and 10−5 were spread onto WLN agar medium and incubated for 7 days at 28 °C. Green colonies (H. uvarum BHu9) and creamy colonies (S. cerevisiae BSc114) were differentiated and counted [23].

After the sugar was completely consumed, 50 mg/L of free SO2 was added. The wines were chemically stabilized, filtered, bottled, and conserved at 16 ± 1 °C until sensorial analysis. Samples of 50 mL were stored at −20 °C in order to carry out volatile composition analysis.

2.5. Chemical Analysis

Glycerol, residual sugars, total acidity and acetic, malic, lactic, and tartaric acid were measured periodically using an ALPHA FT-IR Wine Analyzer (Bruker Optik Gmbh, Ettlingen, Germany). Ethanol concentration was determined according to the OIV OENO 379-2009 ES official method. The pH was measured with a multi-parameter Adwa (AD1030 PHM_MES_6362).

2.6. Sensorial Analysis

After 4 months of bottle stabilization, wines were evaluated by descriptive analysis according to Lawless and Heymann [24]. A well-trained panel carried out the evaluation of 13 sensorial attributes: three color/appearance descriptors (color intensity, red and brown color), five aroma descriptors (mineral note, frutal, floral, chili pepper, and toasted) and five taste parameters (acidity, sweetness, astringency, hotness, and bitterness). The intensity of each attribute was assessed using a structured scale from 0 to 5, where 0 indicates that the descriptor was not perceived and values between 1 and 5 indicate that the intensity of the descriptors was very low to very high. The panel consisted of seven individuals (five males and two females between 35 and 50 years old) from the Wine Sensorial Analysis Department (Instituto Nacional de Vitivinicultura, Mendoza, Argentina). Vinifications were tasted blindly and in duplicate from a constant volume of 30 mL at room temperature.

2.7. Free aromatic Analyses

2.7.1. Solid Phase Extraction (SPE)

The extraction of aroma compounds was performed by adsorption and the molecules were separate elutions from an Isolute ENV+ cartridge (IST Ltd., Mid Glamorgan, UK) packed with 1 g of the highly cross-linked styrene divinylbenzene (SDVB) polymer according to Boido et al. [25] with some modifications.

2.7.2. GC-MS Analyses

GC-MS analyses were conducted using a Shimadzu QP 2020 (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) mass spectrometer. A Carbowax 20 M capillary column (Agilent Technologies, Walt and Jennings Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA) (30m × 0.25mm × 0.25μm film thickness) was used. The experimental conditions were as follows: The initial column temperature was 40 °C (8 min), which was then increased to 180 °C (3 °C/min) and then increased again to 250 °C (20 min) at 20 °C/min; injector temperature, 250 °C; injection mode, split; split ratio, 1:30; volume injected, 1.0 µL; carrier gas H2, 30 kPa; energy 70 eV. The wine aroma components were identified by comparison of their linear retention indices (LRI) determined with a homologous series of n-alkanes (C9–C26), with those from pure standards or reported in the literature according to their elution order with Carbowax 20 M [26,27,28]. Comparison of mass spectral fragmentation patterns with those stored in databases was also performed. GC-MS instrumental procedures using 1-heptanol as an internal standard were applied for quantitative purposes. GC-MS analyses were carried out with two samples of each wine.

2.8. Odor Activity Value (OAV) and Relative Odor Contributions (ROCs)

The contribution of each volatile compound was quantitatively evaluated using Odor Activity Values (OAVs). The OAV was obtained by dividing the mean concentration of each volatile compound by its odor threshold value in a hydroalcoholic solution [29]. The volatile compounds contribute to wine aroma when its concentration in wine is above the perception threshold, therefore, the OAV value is above 1. In this study, the threshold values were obtained from information available in the literature. Moreover, the identified compounds were classified according to aromatic descriptors and grouped in seven aromatic series which were classified according to the associated descriptor: 1, solvent; 2, sweet; 3, herbaceous; 4, floral; 5, fruity; 6, fatty; and 7, toasted.

From the volatile compounds that presented OAV > 1, the relative odor contribution (ROC) was calculated. The relative odor contribution (ROC) represents the percentage of contribution of a particular aroma compound and this was determined as the ratio between the OAV of the respective compound and the total OAV of each wine ((individual OAV/∑OAV) * 100) [30].

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Chemical data and population analysis were expressed as the means ± standard deviation from three repetitions and aromatic analysis as the means of two repetitions. One-way ANOVA was used to evaluate differences between treatments. Statistical analysis was performed using the InfoStat professional version (Cordoba, Argentina, 2016).

3. Results

The current study assessed the contribution of H. uvarum BHu9 and S. cerevisiae BSc114 yeasts to the ethanol content and sensorial and aromatic impact on wine.

3.1. Fermentative Kinetics and Population Dynamics

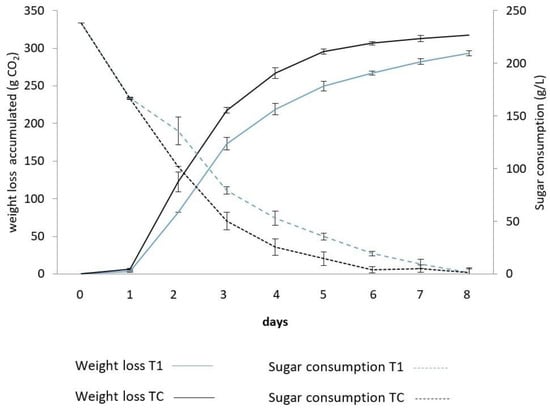

In the present study, fermentative kinetics are represented by sugar consumption and CO2 release in both fermentations: BHu9/BSc114 (T1) and BSc114 (TC) (Figure 1). Both treatments completed alcoholic fermentation after 8 days. During the first 24 h, both vinifications showed a similar sugar consumption, but from day 2 until day 6, T1 exhibited a slower fermentation rate than TC (p < 0.05). During day 7 and 8, sugar consumption was not significantly different (p > 0.05), and at the end of the process, both treatments behaved similarly.

Figure 1.

Release of CO2 (g) and sugar consumption in T1 (BHu9/BSc114) and TC (BSc114 control).

Like the sugar consumption, CO2 release showed a similar behavior for both treatments during the first 24 h. From day 2 until the end, T1 demonstrated a lower rate than TC (BSc114) (p < 0.05). Total CO2 production was 293.33 ± 17 g and 320 ± 10 g for the BHu9/BSc114 co-culture and S. cerevisiae monoculture, respectively (Figure 1).

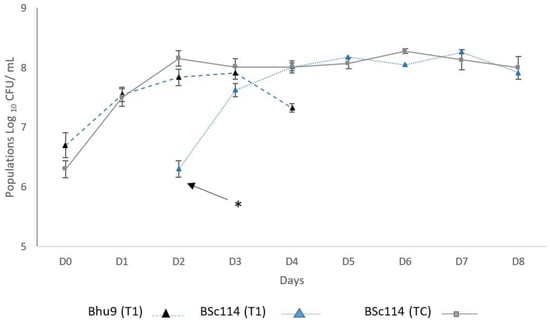

The population dynamics of T1 (H. uvarum BHu9/S. cerevisiae BSc114) and TC (S. cerevisiae BSc114) are shown in Figure 2. H. uvarum BHu9 population increased during the early stages reaching a maximum of 8.18 × 107 cells/mL on day three. During the first 48 h, (previous S. cerevisiae inoculation) BHu9 consumed 102.54 g/L of sugar with an ethanol production of 3.49% v/v. Therefore, when BSc114 was inoculated (after 48 h), the available sugar concentration was 135 g/L. In co-inoculation trials, H. uvarum BHu9 maintained its population up to day 4, after which the concentrations were undetectable with the technique applied in this study. Hence, H. uvarum BHu9 and S. cerevisiae BSc114 coexisted only during 2 days. During this coexistence period, the sugar consumption was 51.74 g/L, which means that the sugar consumption by both strains was less than the consumption by BHu9 before S. cerevisiae inoculation, and the ethanol production at this stage was 5.93% v/v. At the final fermentation stage (day 5 to 8), S. cerevisiae BSc114 consumed 74.67 g/L of sugar, and the average ethanol production was 3.22% v/v. The dynamic population of S. cerevisiae in T1 presented an increase in the number of cells from 2 × 106 cells/mL to 1.82 × 108 cells/mL on day 7, whereas the maximum population achieved by BSc114 (TC, control) was 1.9 × 108 cells/mL on day 6.

Figure 2.

Dynamic populations of T1 (BHu9/BSc114) and TC (BSc114). * indicate the inoculation moment of BSc114 in T1 after 48 h.

3.2. Enological Parameters

The analyses of the main chemical parameters at the end of the fermentations are summarized in Table 1. Both treatments finished with sugar concentrations below 1.8 g/L, indicating that the fermentations had been successfully finished. Ethanol concentration in T1 was significantly lower (12.63 ± 0.05% v/v) than TC (13.15 ± 0.28% v/v), representing an average reduction of 0.52% v/v. Likewise, pH values were lowest in wines produced with co-cultures, but tartaric acid was higher compared to control (TC) wines. No significant differences were observed for acetic, malic and lactic acid, or for glycerol and total acidity under the experimental conditions.

Table 1.

Principal chemical parameters in wines obtained from BHu9/Bcs114 co-inoculation and BSc114 control.

3.3. Aromatic Composition

Volatile products of the fermented musts were quantified by SPE-GC-MS according to Boido et al. (2003). Table 2 shows volatile compounds and their concentrations, odorant descriptors, perception thresholds, odorant activity values (OAVs), and aromatic series found in the Malbec wines analyzed. A total of 38 volatile compounds were identified and quantified, and classified into four groups: esters (ethyl and acetate esters), higher alcohols, fatty acids, and lactones.

Table 2.

Aromatic description of wines obtained (mean and SD of two measure).

Alcohols formed the most abundant group of volatile compounds, followed by esters, fatty acids and lactones. Higher alcohols represented 98.14 and 98.45% of the total aroma content in T1 and TC wines, respectively, while esters and fatty acids constituted 1.77–1.03% and 0.019–0.49% in T1 and TC wines, respectively (Table 2).

Overall, the total concentration of higher alcohols and fatty acids was higher in control treatment TC, fermented with S. cerevisiae BSc114, than in wines produced by the sequential fermentation of H. uvarum BHu9/S. cerevisiae BSc114 (T1). In contrast, esters and lactones (γ-butyrolactone and γ-valerolactone) content was higher in T1 than in TC. These compounds represented 1.77 and 1.03 % in esters, in T1 and TC respectively. The lactones proportions were 0.06 % and 0.04 % in T1 and TC respectively. (Table 2).

Some compounds such as ethyl hexanoate, ethyl decanoate, 3-ethoxy-1-propanol, isoamyl acetate, and γ-butyrolactone were detected at higher concentrations in T1 than in TC (p < 0.05). In contrast, S. cerevisiae BSc114 fermentation showed higher concentrations of ethyl octanoate, 3-methyl-1-butanol, 3-(methyl thio)-1-propanol, 2-phenylethanol, and γ-valerolactone compared to wines obtained with BHu9/BSc114 (p < 0.05) (Table 2).

Compounds such us ethyl hexanoate (fruity, apple), ethyl octanoate (pineapple, pear), isoamyl acetate (banana), γ-butyrolactone (caramel, coconut), and γ-valerolactone (sweet, coconut) showed OAVs > 1 in both treatments. Comparing pure with mixed, fermented 3-ethoxy-1-propanol (ripe pear) exhibited an OAV > 1 only in T1, and 3-(methyl thio)-1-propanol (cooked vegetables) showed an OAV > 1 in wine fermented by the S. cerevisiae Bc114 monoculture (Table 2).

Table 3 presents compounds with an OAV > 1 and their relative odor contribution (ROC). When considering the ester contribution to the odorant composition, ethyl octanoate greatly contributed to wines obtained with BHu9/BSc114 (49.35%), while isoamyl acetate was the main contributor to the control treatment fermented with pure BSc114 control. The higher alcohols that demonstrated major contributions to wines in both treatments were 3-methyl-1-butanol and 2-phenylethanol, but their relative odor contributions were higher in TC wines.

Table 3.

Compounds with an OAV > 1 and their relative odor contribution (ROC) in T1 and TC wines.

Figure 3 shows the aromatic profile of the analyzed wines based on the sum of the components with an OAV > 1 and ROC values according to each descriptor. Wines fermented with BSc114 were related to the aromatic “floral”, “solvent”, “herbaceous” and “sweet” families, while co-culture fermented wines were characterized by “frutal” descriptors.

Figure 3.

Aromatic profile of wines produced by BHu9/BSc114 (T1) and BSc114 (TC control).

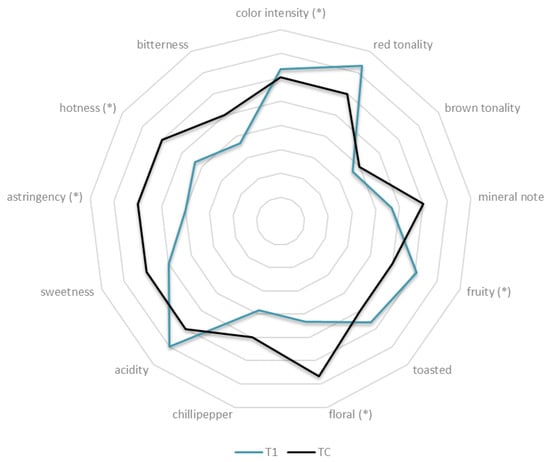

3.4. Sensorial Analysis

Figure 4 shows the sensorial analyses of the wines obtained. Wines fermented with H. uvarum BHu9/S. cerevisiae BSc114 (T1) could be defined as fruity (p < 0.05). These results are in agreement with the aromatic profile obtained with ROC analysis. Another parameter that significantly affected reduced ethanol wines (T1) was color intensity. Wines produced with S. cerevisiae BSc114 (TC) were more related to the floral descriptor, which is in agreement with the ROC results due to 2-phenylethanol concentration; moreover, these wines were associated with astringency and hotness mouthfeel.

Figure 4.

Sensory analysis of wines obtained from BHu9/BSc114 (T1) and BSc114 (TC). (*) Difference significant at 95% confidence level.

4. Discussion

The current wine market requires wines with lower ethanol concentrations and complex flavor and color perception. Several microbiological strategies have been proposed in order to obtain these characteristics. The present study intends to verify the behavior of selected yeasts regarding ethanol production and the sensorial impact on the wine quality.

Several studies have reported reduced ethanol levels with sequential inoculations of non-Saccharomyces and Saccharomyces yeasts and under different winemaking conditions [4,16,31]. It is well known that H. uvarum is the most representative yeast species found on grape surfaces showing prevalence during early stages of spontaneous alcoholic fermentation [32]. This yeast has several characteristics that could be used to reduce ethanol content in wines [21]. In the current study, inoculation of H. uvarum BHu9 prior to inoculation of S. cerevisiae BSc114 demonstrated a sugar consumption of 35.7 g/L for 1% of ethanol produced. In contrast, S. cerevisiae control (TC) used 17.5 g /L of sugar for 1% of ethanol produced. It is reported that S. cerevisiae yeast uses 16.83 to 17 g/L on average [1]. The decrease in ethanol production can sometimes be explained by an increase in glycerol and acetic acid. However, in the present study, both glycerol and acetic acid did not show significant differences. Sugars were probably partially consumed through the oxidative pathway to produce biomass and other products.

It must be highlighted that when both strains remained together, sugar consumption was lower than in the H. uvarum monoculture (prior to S. cerevisiae inoculation). There is evidence that presence of non-Saccharomyces yeasts in the early stages of fermentation could affect the metabolic activity of S. cerevisiae, probably encouraging a competition for nutrients [33,34,35]. For example, Bisson et al. [36] demonstrated that K. apiculata consumed thiamine and other micronutrients, generating inefficiency in the metabolic development of S. cerevisiae. Another study established that immobilized Starmerella bombicola cells in a mixed fermentation affected decarboxylase and alcohol dehydrogenase levels of S. cerevisiae [37]. Recently, the research of Petitgonnet et al. [38] demonstrated that sequential culture between Lachaceae thermotholerans and S. cerevisiae provokes a negative interaction between the two species to the detriment of S. cerevisiae, due to a cell–cell contact mechanism and essential nutrients uptake. When H. uvarum and S. cerevisiae are mixed inoculated, the cultivability of H. uvarum is significantly affected; however, the final ethanol concentrations are lower compared to the pure culture of S. cerevisiae [39]. Nevertheless, to answer the results of this work, further studies should be carried out to fully understand the interactions between H. uvarum and S. cerevisiae strains employed in the present study.

With respect to the aromatic composition, many studies have shown that non-Saccharomyces yeasts such as Candida, Debaryomyces, Pichia, Hansenula, and Hanseniaspora, that display oxidative metabolism and/or are weakly fermentative produced higher ester levels than a single S. cerevisiae culture [40]. In accordance, the total ester concentrations in wines produced by H. uvarum/S. cerevisiae co-cultures were superior to that of wines produced by control treatment. The co-inoculation showed higher levels of ethyl hexanoate, ethyl octanoate and ethyl decanoate which allowed the “fruity” aromatic profile of the wines.

Fusel alcohol production was higher in wine fermented with a monoculture of S. cerevisiae. Fusel alcohol production is related to amino acid production by yeasts, which varies according to genera, species and strain [41]. S. cerevisiae yeasts have been reported to produce higher quantities of these compounds compared with certain non-Saccharomyces yeasts [42]. The aromatic series that best describes the TC profile is “floral”, which is associated with 2-phenylethanol levels. As was expected, sensorial analysis of TC wine related it to floral descriptors (p < 0.05).

It is well known that ethanol significantly affects the sensorial perception of wines [43]; for example, it decreases the perception of higher alcohols and aldehydes and shows a similar effect for ethyl esters [44]. According to our results, wines obtained from a BSc114 (TC) monoculture could be associated with attributes such us astringency, bitterness, hotness, and sweetness, which is in agreement with the results by Tilloy et al. [45]. The authors found that high ethanol levels enhanced the perception of the abovementioned attributes. In contrast, wines with lower ethanol levels obtained with H. uvarum/S. cerevisiae in the present study were related to red fruit by the sensorial panel (p < 0.05). Although the control treatment presented elevated concentrations of chemical compounds which are commonly related to fruity descriptors, it has been reported that high ethanol contents can mask certain flavor-related volatile compounds like those related to fruity and floral profiles [46].

To our knowledge, this is the first time that a H. uvarum species, submitted to a previous selection process, has been proposed to carry out sequential fermentations with S. cerevisiae under optimized conditions to reduce ethanol in wines. The results obtained in the present study have demonstrated the impact of this co-culture on the ethanol concentration and the chemical aromatic composition; and, in addition, it has evidenced that ethanol levels affect sensorial perception. Therefore, the present study could be considered an additional step to a successful change in the wine industry to face current consumers’ demands. It is possible, however, that more research is necessary in order to fully understand the impact of this co-culture on a major production scale.

Author Contributions

Investigation, M.V.M.; Methodology, M.V.M., Y.P.M., C.G. and E.D.; Project administration, Y.P.M., M.E.T., F.V. and E.D.; Supervision, F.C.; Writing—original draft, M.V.M., F.V. and E.D.; Writing—review & editing, M.V.M., Y.P.M., M.C., L.M., M.E.T. and F.C.

Funding

This research was funded by [UNSJ-SECITI] grant number [3635-2015-2017] and [UNSJ-CICITCA] grant number [1531-2016].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zamora, F. Dealcoholised Wines and Low-Alcohol Wines. In Wine Safety, Consumer Preference, and Human Health; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 163–182. [Google Scholar]

- De Orduna, R.M. Climate change associated effects on grape and wine quality and production. Food Res. Int. 2010, 43, 1844–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meillon, S.; Dugas, V.; Urbano, C.; Schlich, P. Preference and acceptability of partially dealcoholized white and red wines by consumers and professionals. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2010, 61, 42–52. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras, A.; Hidalgo, C.; Henschke, P.A.; Chambers, P.J.; Curtin, C.; Varela, C. Evaluation of non-Saccharomyces yeasts for the reduction of alcohol content in wine. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 1670–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, U.; Noble, A.C. The effect of ethanol, catechin concentration, and pH on sourness and bitterness of wine. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1994, 45, 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- King, E.S.; Heymann, H. The effect of reduced alcohol on the sensory profiles and consumer preferences of white wine. J. Sens. Stud. 2014, 29, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kliewer, W.M.; Dokoozlian, N.K. Leaf area/crop weight ratios of grapevines: Influence on fruit composition and wine quality. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2005, 56, 170–181. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, R.R.; Blackmore, D.H.; Clingeleffer, P.R.; Tarr, C.R. Rootstock effects on salt tolerance of irrigated field-grown grapevines (Vitis vinifera L. cv. Sultana). 3. Fresh fruit composition and dried grape quality. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2007, 13, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chorti, E.; Guidoni, S.; Ferrandino, A.; Novello, V. Effect of different cluster sunlight exposure levels on ripening and anthocyanin accumulation in Nebbiolo grapes. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2010, 61, 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Palliotti, A.; Panara, F.; Silvestroni, O.; Lanari, V.; Sabbatini, P.; Howell, G.S.; Gatti, M.; Poni, S. Influence of mechanical postveraison leaf removal apical to the cluster zone on delay of fruit ripening in Sangiovese (Vitis vinifera L.) grapevines. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2013, 19, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidtke, L.M.; Blackman, J.W.; Agboola, S.O. Production technologies for reduced alcoholic wines. J. Food Sci. 2012, 77, R25–R41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catarino, M.; Mendes, A. Dealcoholizing wine by membrane separation processes. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. 2011, 12, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belisario-Sanchez, Y.Y.; Taboada-Rodriguez, A.; Marin-Iniesta, F.; Lopez-Gomez, A. Dealcoholized wines by spinning cone column distillation: Phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity measured by the 1, 1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl method. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 6770–6778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quirós, M.; Rojas, V.; Gonzalez, R.; Morales, P. Selection of non-Saccharomyces yeast strains for reducing alcohol levels in wine by sugar respiration. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2014, 181, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varela, C.; Dry, P.R.; Kutyna, D.R.; Francis, I.L.; Henschke, P.A.; Curtin, C.D.; Chambers, P.J. Strategies for reducing alcohol concentration in wine. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2015, 21, 670–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englezos, V.; Rantsiou, K.; Cravero, F.; Torchio, F.; Ortiz-Julien, A.; Gerbi, V.; Rolle, L.; Cocolin, L. Starmerella bacillaris and Saccharomyces cerevisiae mixed fermentations to reduce ethanol content in wine. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 5515–5526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jolly, N.P.; Varela, C.; Pretorius, I.S. Not your ordinary yeast: Non-Saccharomyces yeasts in wine production uncovered. FEMS Yeast Res. 2014, 14, 215–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, C.; Sengler, F.; Solomon, M.; Curtin, C. Volatile flavour profile of reduced alcohol wines fermented with the non-conventional yeast species Metschnikowia pulcherrima and Saccharomyces uvarum. Food Chem. 2016, 209, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, R.; Quirós, M.; Morales, P. Yeast respiration of sugars by non-Saccharomyces yeast species: A promising and barely explored approach to lowering alcohol content of wines. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 29, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, V.; Valera, M.; Medina, K.; Boido, E.; Carrau, F. Oenological impact of the Hanseniaspora/Kloeckera yeast genus on wines—A review. Fermentation 2018, 4, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestre Furlani, M.V.; Maturano, Y.P.; Combina, M.; Mercado, L.A.; Toro, M.E.; Vazquez, F. Selection of non-Saccharomyces yeasts to be used in grape musts with high alcoholic potential: A strategy to obtain wines with reduced ethanol content. FEMS Yeast Res. 2017, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maturano, Y.P.; Mestre, M.V.; Kuchen, B.; Toro, M.E.; Mercado, L.A.; Vazquez, F.; Combina, M. Optimization of fermentation-relevant factors: A strategy to reduce ethanol in red wine by sequential culture of native yeasts. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019, 289, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pallmann, C.L.; Brown, J.A.; Olineka, T.L.; Cocolin, L.; Mills, D.A.; Bisson, L.F. Use of WL medium to profile native flora fermentations. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2001, 52, 198–203. [Google Scholar]

- Lawless, H.T.; Heymann, H. Physiological and psychological foundations of sensory function. In Sensory Evaluation of Food; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 19–56. [Google Scholar]

- Boido, E.; Lloret, A.; Medina, K.; Fariña, L.; Carrau, F.; Versini, G.; Dellacassa, E. Aroma composition of Vitis vinifera cv. Tannat: The typical red wine from Uruguay. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 5408–5413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mondello, L. Mass Spectra of Flavors and Fragrances of Natural and Synthetic Compounds, 3rd ed.; MS Wil GmbH: Zurich, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, R.P. Identification of Essential Oil Components by Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry; Allured publishing corporation: Carol Stream, IL, USA, 2007; Volume 456. [Google Scholar]

- McLafferty, F.W.; Stauffer, D.B. The Wiley/NBS Registry of Mass Spectral Data; Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hellin, P.; Manso, A.; Flores, P.; Fenoll, J. Evolution of aroma and phenolic compounds during ripening of superior seedless grapes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 6334–6340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welke, J.E.; Zanus, M.; Lazzarotto, M.; Zini, C.A. Quantitative analysis of headspace volatile compounds using comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography and their contribution to the aroma of Chardonnay wine. Food Res. Int. 2014, 59, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tristezza, M.; Tufariello, M.; Capozzi, V.; Spano, G.; Mita, G.; Grieco, F. The oenological potential of Hanseniaspora uvarum in simultaneous and sequential co-fermentation with Saccharomyces cerevisiae for industrial wine production. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleet, G.H.; Heard, G.M. Yeasts-growth during fermentation. In Wine Microbiology and Biotechnology; Fleet, G.H., Harwood Academic, Eds.; CRC Press: Chur, Switzerland, 1993; pp. 27–54. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza, L.M.; de Nadra, M.C.M.; Farías, M.E. Kinetics and metabolic behavior of a composite culture of Kloeckera apiculata and Saccharomyces cerevisiae wine related strains. Biotechnol. Lett. 2007, 29, 1057–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domizio, P.; Romani, C.; Lencioni, L.; Comitini, F.; Gobbi, M.; Mannazzu, I.; Ciani, M. Outlining a future for non-Saccharomyces yeasts: Selection of putative spoilage wine strains to be used in association with Saccharomyces cerevisiae for grape juice fermentation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2011, 147, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzzi, G.; Arfelli, G.; Schirone, M.; Corsetti, A.; Perpetuini, G.; Tofalo, R. Effect of grape indigenous Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains on Montepulciano d’Abruzzo red wine quality. Food Res. Int. 2012, 46, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisson, L.F. Stuck and sluggish fermentations. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1999, 50, 107–119. [Google Scholar]

- Milanovic, V.; Ciani, M.; Oro, L.; Comitini, F. Starmerella bombicola influences the metabolism of Saccharomyces cerevisiae at pyruvate decarboxylase and alcohol dehydrogenase level during mixed wine fermentation. Microb. Cell Factories 2012, 11, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petitgonnet, C.; Klein, G.L.; Roullier-Gall, C.; Schmitt-Kopplin, P.; Quintanilla-Casas, B.; Vichi, S.; Diane, J.D.; Alexandre, H. Influence of cell-cell contact between L. thermotolerans and S. cerevisiae on yeast interactions and the exo-metabolome. Food Microbiol. 2019, 83, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Mas, A.; Esteve-Zarzoso, B. Interaction between Hanseniaspora uvarum and Saccharomyces cerevisiae during alcoholic fermentation. Int. J. Food Microb. 2015, 206, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erten, H.; Campbell, I. The production of low-alcohol wines by aerobic yeasts. J. Inst. Brew. 1953, 59, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giudici, P.; Romano, P.; Zambonelli, C. A biometric study of higher alcohol production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Can. J. Microbiol. 1990, 36, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateos, J.R.; Pérez-Nevado, F.; Fernández, M.R. Influence of Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast strain on the major volatile compounds of wine. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2006, 40, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guth, H.; Sies, A. Flavour of wines: Towards an understanding by reconstitution experiments and an analysis of ethanol’s effect on odour activity of key compounds. In Proceedings of the 11th Australian Wine Industry Technical Conference, Glen Osmond, SA, Australia, 7–11 October 2002; pp. 128–139. [Google Scholar]

- Conner, J.M.; Birkmyre, L.; Paterson, A.; Piggott, J.R. Headspace concentrations of ethyl esters at different alcoholic strengths. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1998, 77, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilloy, V.; Ortiz-Julien, A.; Dequin, S. Reduction of ethanol yield and improvement of glycerol formation by adaptive evolution of the wine yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae under hyperosmotic conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 2623–2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escudero, A.; Gogorza, B.; Melus, M.A.; Ortin, N.; Cacho, J.; Ferreira, V. Characterization of the aroma of a wine from Maccabeo. Key role played by compounds with low odor activity values. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 3516–3524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).