Effects of Autochthonous Starter Cultures on the Quality Characteristics of Traditionally Produced Sucuk

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Production of Sucuk

2.3. Microbiological Analysis

2.4. pH and Water Activity (aw)

2.5. Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances (TBARS)

2.6. Instrumental Color

2.7. Volatile Compound Analysis

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Microbiological Results

3.2. pH, aw, and TBARS Values

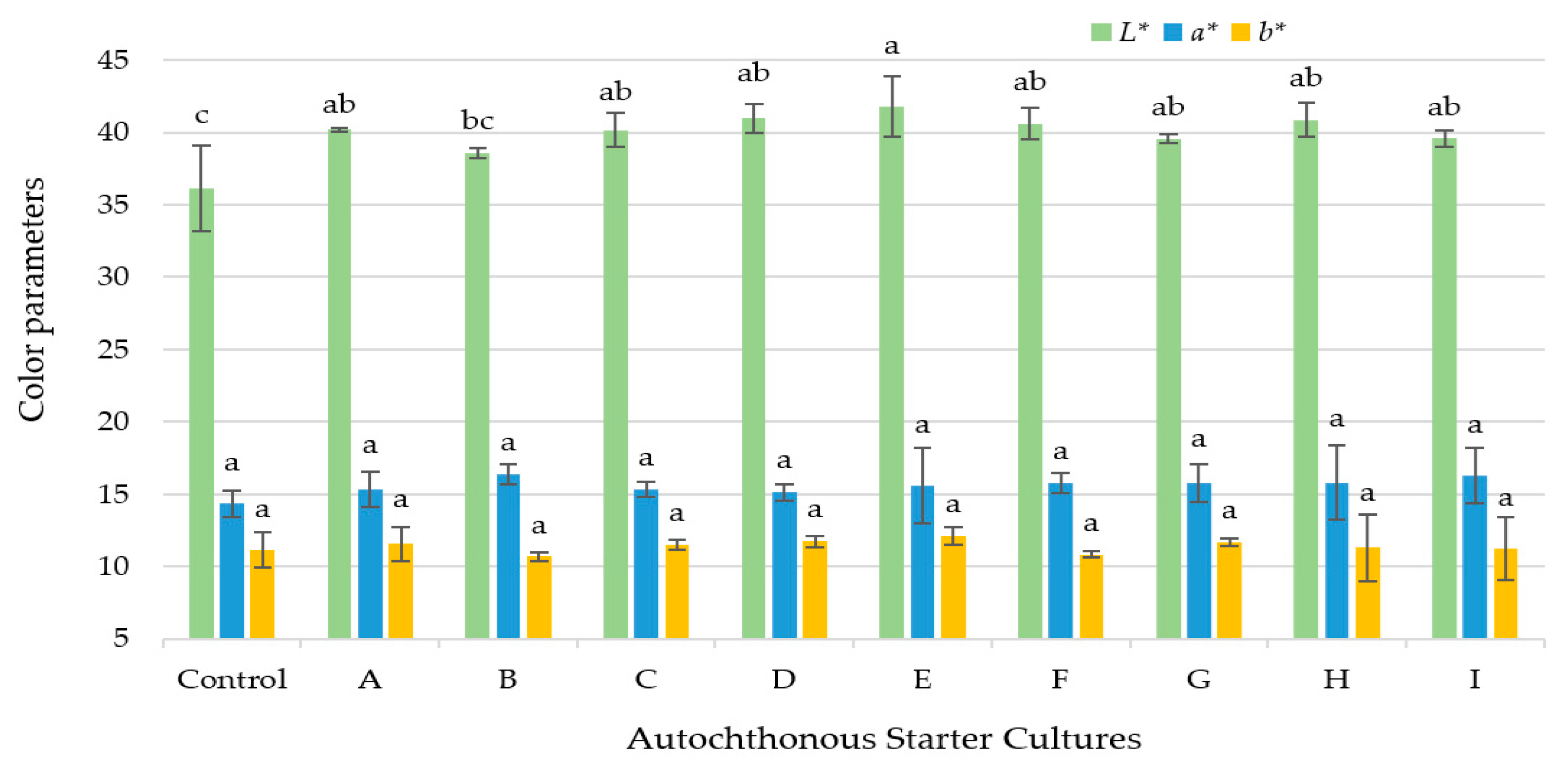

3.3. Color Values

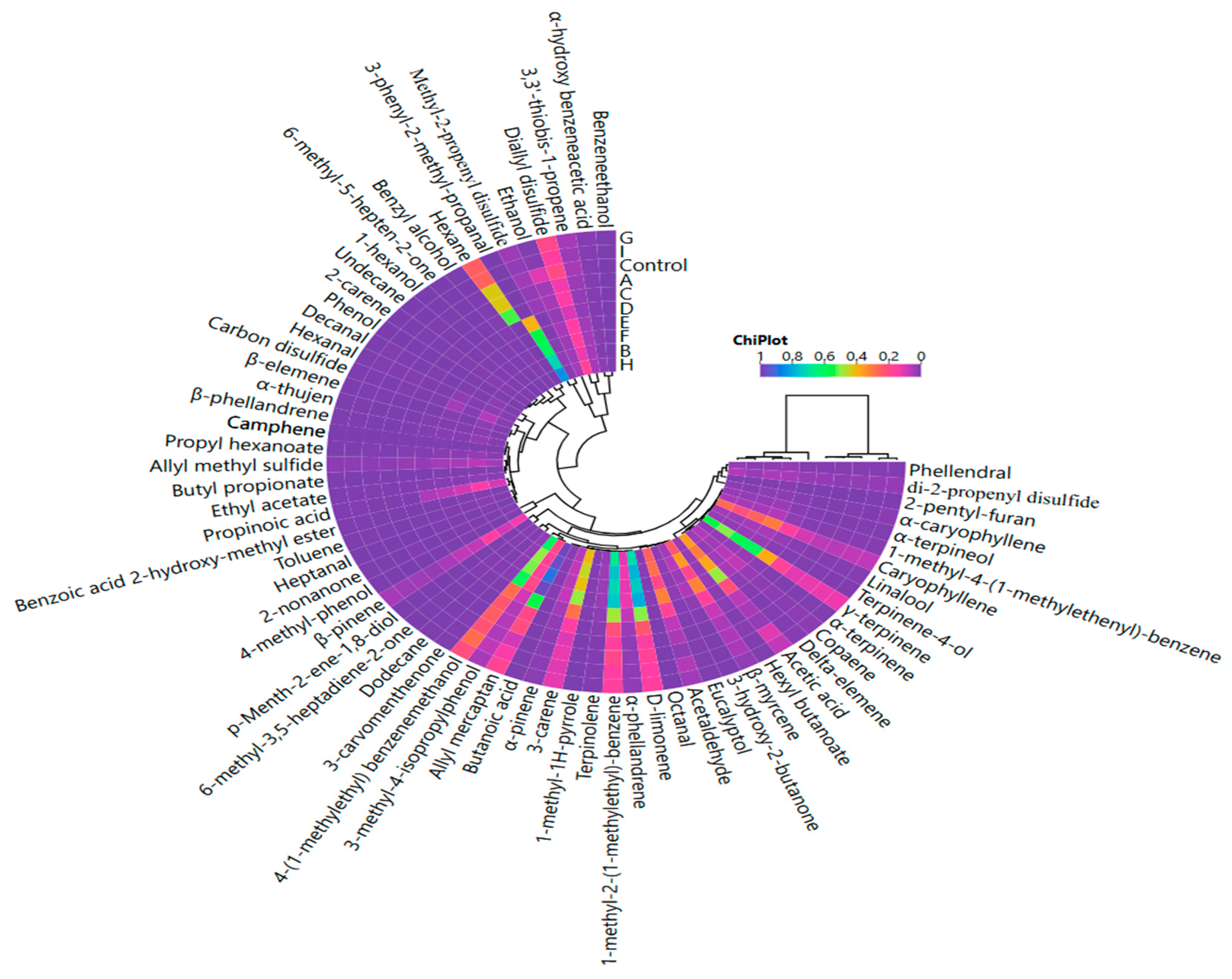

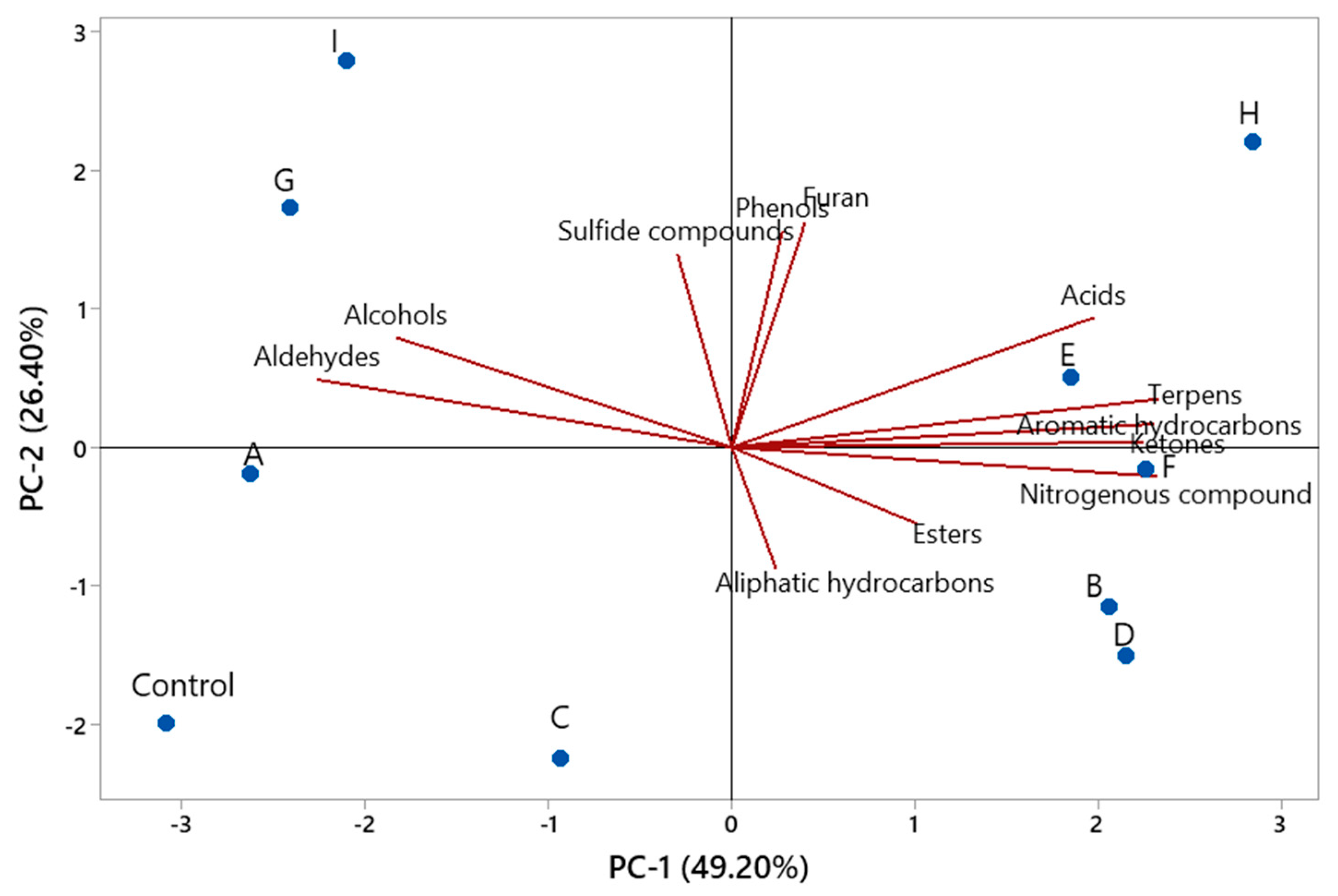

3.4. Volatile Compounds

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ross, R.P.; Morgan, S.; Hill, C. Preservation and fermentation: Past, present and future. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2002, 79, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cocolin, L.; Dolci, P.; Rantsiou, K. Biodiversity and dynamics of meat fermentations: The contribution of molecular methods for a better comprehension of a complex ecosystem. Meat Sci. 2011, 89, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aro, J.M.A.; Nyam-Osor, P.; Tsuji, K.; Shimada, K.; Fukushima, M.; Sekikawa, M. The effect of starter cultures on proteolytic changes and amino acid content in fermented sausages. Food Chem. 2010, 119, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sionek, B.; Szydłowska, A.; Küçükgöz, K.; Kołożyn-Krajewska, D. Traditional and new microorganisms in lactic lactic acid fermentation of food. Fermentation 2023, 9, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonomo, M.G.; Ricciardi, A.; Salzano, G. Influence of autochthonous starter cultures on microbial dynamics and chemical-physical features of traditional fermented sausages of Basilicata region. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 27, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, F.; Tucci, P.; Del Matto, I.; Marino, L.; Amadoro, C.; Colavita, G. Autochthonous cultures to improve safety and standardize quality of traditional dry fermented meats. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaban, G. Sucuk and pastırma: Microbiological changes and formation of volatile compounds. Meat Sci. 2013, 95, 912–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassi, D.; Puglisi, E.; Cocconcelli, P.S. Comparing natural and selected starter cultures in meat and cheese fermentations. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2015, 2, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargozari, M.; Moini, S.; Basti, A.A.; Emam-Djomeh, Z.; Gandomi, H.; Martin, I.R.; Ghasemlou, M.; Carbonell-Barrachina, Á.A. Effect of autochthonous starter cultures isolated from Siahmazgi cheese on physicochemical, microbiological and volatile compound profiles and sensorial attributes of sucuk, a Turkish dry-fermented sausage. Meat Sci. 2014, 97, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lücke, F.-K. Utilization of microbes to process and preserve meat. Meat Sci. 2000, 56, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Z.; Wang, L.; Ge, Y.; An, Y.; Sun, X.; Xue, K.; Xie, H.; Wang, R.; Li, J.; Chen, L. Screening, identification, and application of superior starter cultures for fermented sausage production from Traditional Meat Products. Fermentation 2025, 11, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Feng, M.-Q.; Sun, J. Influence of mixed starters on the degradation of proteins and the formation of peptides with antioxidant activities in dry fermented sausages. Food Control 2021, 123, 107743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talon, R.; Leroy, S.; Lebert, I.; Giammarinaro, P.; Chacornac, J.-P.; Latorre-Moratalla, M.; Vidal-Carou, C.; Zanardi, E.; Conter, M.; Lebecque, A. Safety improvement and preservation of typical sensory qualities of traditional dry fermented sausages using autochthonous starter cultures. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2008, 126, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baka, A.M.; Papavergou, E.J.; Pragalaki, T.; Bloukas, J.G.; Kotzekidou, P. Effect of selected autochthonous starter cultures on processing and quality characteristics of Greek fermented sausages. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 44, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaban, G.; Kaya, M. Identification of lactic acid bacteria and Gram-positive catalase-positive cocci isolated from naturally fermented sausage (Sucuk). J. Food Sci. 2008, 73, M385–M388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaban, G.; Kaya, M. Effects of Lactobacillus plantarum and Staphylococcus xylosus on the quality characteristics of dry fermented sausage “Sucuk”. J. Food Sci. 2009, 74, S58–S63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiloğlu, A. Functional and technological characterization of lactic acid bacteria isolated from Turkish dry-fermented sausage (sucuk). Braz. J. Microbiol. 2022, 53, 959–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, I.; Sagdic, O.; Yetim, H. Effects of autochthonous yeast cultures on some quality characteristics of traditional Turkish fermented sausage “Sucuk”. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2021, 41, 196–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaban, G.; Sallan, S.; Çinar Topçu, K.; Sayın Börekçi, B.; Kaya, M. Assessment of technological attributes of autochthonous starter cultures in Turkish dry fermented sausage (sucuk). Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 57, 4392–4399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akköse, A.; Oğraş, Ş.Ş.; Kaya, M.; Kaban, G. Microbiological, physicochemical and sensorial changes during the Rripening of sucuk, a traditional Turkish dry-fermented sausage: Effects of autochthonous strains, sheep tail fat and ripening rate. Fermentation 2023, 9, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.-S.; Wang, C.-Y.; Hu, Y.-Y.; Yang, L.; Xu, B.-C. Enhancement of fermented sausage quality driven by mixed starter cultures: Elucidating the perspective of flavor profile and microbial communities. Food Res. Int. 2024, 178, 113951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.; Wang, H.; Song, X.; Xu, N.; Sun, J.; Xu, X. Effects of different mixed starter cultures on microbial communities, taste and aroma compounds of traditional Chinese fermented sausages. Food Chem. X 2024, 21, 101225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhou, C.; Ning, J.; Wang, S.; Nie, Q.; Wang, W.; Zhang, J.; Ji, L. Effect of fermentation by Pediococcus pentosaceus and Staphylococcus carnosus on the metabolite profile of sausages. Food Res. Int. 2022, 162, 112096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaya, M.; Sayın, B.; Çinar Topçu, K.; Karadayı, M.; Kamiloğlu, A.; Güllüce, M.; Kaban, G. Genotypic and technological characterization of lactic acid bacteria and coagulase-negative staphylococci isolated from sucuk: A Preliminary Screening of Potential Starter Cultures. Foods 2025, 14, 3495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgart, J.; Eigener, V.; Firnhaber, J.; Hildebrant, G.; Reenen Hoekstra, E.S.; Samson, R.A.; Spicher, G.; Timm, F.; Yarrow, D.; Zschaler, R. Mikrobiologische Untersuchung von Lebensmitteln; Behr’s GmbH &Co.: Hamburg, Germany, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lemon, D.W. An Improved TBA Test for Rancidity; Fisheries and Marine Service: Halifax, NS, Canada, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- ChiPlot. Available online: https://www.chiplot.online/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Lücke, F.K. Mikrobiologische Vorgänge bei der Herstellung von Rohwurst und Rohschinken. In Mikrobiologie und Qualität von Rohwurst und Rohschinken; Bundesanstalt für Fleischforschung: Kulmbach, Germany, 1985; pp. 85–102. [Google Scholar]

- Agüero, N.d.L.; Frizzo, L.S.; Ouwehand, A.C.; Aleu, G.; Rosmini, M.R. Technological characterisation of probiotic Lactic Acid Bacteria as Starter Cultures for Dry Fermented Sausages. Foods 2020, 9, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaban, G.; Kaya, M. Effects of Staphylococcus carnosus on quality characteristics of sucuk (Turkish dry-fermented sausage) during ripening. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2009, 18, 150–156. [Google Scholar]

- Du, S.; Cheng, H.; Ma, J.-K.; Li, Z.-J.; Wang, C.-H.; Wang, Y.-L. Effect of starter culture on microbiological, physiochemical and nutrition quality of Xiangxi sausage. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 811–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbiere Morot-Bizot, S.; Leroy, S.; Talon, R. Monitoring of staphylococcal starters in two French processing plants manufacturing dry fermented sausages. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2007, 102, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, B.; Díez, V. The effect of nitrite and starter culture on microbiological quality of “chorizo”—A Spanish dry cured sausage. Meat Sci. 2002, 60, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casquete, R.; Benito, M.J.; Martín, A.; Ruiz-Moyano, S.; Aranda, E.; Córdoba, M.G. Microbiological quality of salchichón and chorizo, traditional Iberian dry-fermented sausages from two different industries, inoculated with autochthonous starter cultures. Food Control 2012, 24, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casaburi, A.; Aristoy, M.-C.; Cavella, S.; Di Monaco, R.; Ercolini, D.; Toldrá, F.; Villani, F. Biochemical and sensory characteristics of traditional fermented sausages of Vallo di Diano (Southern Italy) as affected by the use of starter cultures. Meat Sci. 2007, 76, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, R.; Munekata, P.E.; Agregán, R.; Lorenzo, J.M. Effect of commercial starter cultures on free amino acid, biogenic amine and free fatty acid contents in dry-cured foal sausage. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 71, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palavecino Prpich, N.Z.; Castro, M.P.; Cayré, M.E.; Garro, O.A.; Vignolo, G.M. Indigenous starter cultures to improve quality of artisanal dry fermented sausages from chaco (Argentina). Int. J. Food Sci. 2015, 2015, 931970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Jin, Y.; Ma, C.; Song, H.; Li, H.; Wang, Z.; Xiao, S. Physico-chemical characteristics and free fatty acid composition of dry fermented mutton sausages as affected by the use of various combinations of starter cultures and spices. Meat Sci. 2011, 88, 761–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, J.M.; Gómez, M.; Purriños, L.; Fonseca, S. Effect of commercial starter cultures on volatile compound profile and sensory characteristics of dry-cured foal sausage. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 1194–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-González, M.; Fonseca, S.; Centeno, J.A.; Carballo, J. Biochemical changes during the manufacture of Galician Chorizo sausage as affected by the addition of autochthonous starter cultures. Foods 2020, 9, 1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pragalaki, T.; Bloukas, J.G.; Kotzekidou, P. Inhibition of Listeria monocytogenes and Escherichia coli O157:H7 in liquid broth medium and during processing of fermented sausage using autochthonous starter cultures. Meat Sci. 2013, 95, 458–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Du, B.; Zhao, L.; Jin, Y.; Su, L.; Tian, J.; Wu, J. The effect of different starter cultures on biogenic amines and quality of fermented mutton sausages stored at 4 and 20°C temperatures. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 4472–4483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, R.; Fang, Y.; Lu, W.; Zhong, Y.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, F. Rethinking salt in dry-cured meats: Innovations for a healthier and flavorful future. Food Rev. Int. 2025, 41, 2437–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škaljac, S.; Jokanović, M.; Tomović, V.; Šojić, B.; Ikonić, P.; Peulić, T.; Ivić, M.; Vranešević, J.; Kartalović, B. Color characteristics and content of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons of traditional dry fermented sausages throughout processing in controlled conditions. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 2022, 42, 3124–3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ba, H.; Seo, H.-W.; Kim, J.-H.; Cho, S.-H.; Kim, Y.-S.; Ham, J.-S.; Park, B.-Y.; Kim, H.-W.; Kim, T.-B.; Seong, P.-N. The effects of starter culture types on the technological quality, lipid oxidation and biogenic amines in fermented sausages. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 74, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordóñez, J.A.; Hierro, E.M.; Bruna, J.M.; de la Hoz, L. Changes in the components of dry-fermented sausages during ripening. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 1999, 39, 329–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, M.A.; Saldaña, E.; da Silva Pinto, J.S.; Contreras-Castillo, C.J.; Sentandreu, M.A.; Fadda, S.G. A peptidomic approach of meat protein degradation in a low-sodium fermented sausage model using autochthonous starter cultures. Food Res. Int. 2018, 109, 368–379, Erratum in Food Res. Int. 2019, 123, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viallon, C.; Berdagué, J.L.; Montel, M.C.; Talon, R.; Martin, J.F.; Kondjoyan, N.; Denoyer, C. The effect of stage of ripening and packaging on volatile content and flavour of dry sausage. Food Res. Int. 1996, 29, 667–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdagué, J.L.; Monteil, P.; Montel, M.C.; Talon, R. Effects of starter cultures on the formation of flavour compounds in dry sausage. Meat Sci. 1993, 35, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hierro, E.; de la Hoz, L.; Ordóñez, J.A. Contribution of the microbial and meat endogenous enzymes to the free amino acid and amine contents of dry fermented sausages. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1999, 47, 1156–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito, M.J.; Rodríguez, M.; Martín, A.; Aranda, E.; Córdoba, J.J. Effect of the fungal protease EPg222 on the sensory characteristics of dry fermented sausage “salchichón” ripened with commercial starter cultures. Meat Sci. 2004, 67, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, M.C.; Kerry, J.P.; Arendt, E.K.; Kenneally, P.M.; McSweeney, P.L.H.; O’Neill, E.E. Characterization of proteolysis during the ripening of semi-dry fermented sausages. Meat Sci. 2002, 62, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cao, Z.; Yu, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, K. Effect of inoculating mixed starter cultures of Lactobacillus and Staphylococcus on bacterial communities and volatile flavor in fermented sausages. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2023, 12, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyer, A.; Ertaş, A.H.; Üzümcüoğlu, Ü. Effect of processing conditions on the quality of naturally fermented Turkish sausages (sucuks). Meat Sci. 2005, 69, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGorrin, R.J. The significance of volatile sulfur compounds in food flavors. In Volatile Sulfur Compounds in Food; Qian, M.C., Fan, X., Mahattanatawee, K., Eds.; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; pp. 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Aziz, T.; Bai, R.; Zhang, X.; Shahzad, M.; Sameeh, M.Y.; Khan, A.A.; Dablool, A.S.; Zhu, Y. Dynamic change of bacterial diversity, metabolic pathways, and flavor during ripening of the Chinese fermented sausage. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 990606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, W.; Zhao, W.; Li, M.; Yue, X. Microbial succession in representative fermented sausages: Driving flavor development and variations across Eastern and Western products. Food Sci. Anim. Prod. 2025, 3, 9240128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutsche, K.A.; Tran, T.B.T.; Vogel, R.F. Production of volatile compounds by Lactobacillus sakei from branched chain α-keto acids. Food Microbiol. 2012, 29, 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores, M. Understanding the implications of current health trends on the aroma of wet and dry cured meat products. Meat Sci. 2018, 144, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, M.; Kaban, G. Volatile compounds of sucuk, a dry fermented sausage: The effects of ripening rate, autochthonous starter cultures and fat type. Foods 2024, 13, 3839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, L.; Pan, D.; Guo, T.; Ren, H.; Wang, L. Role of Lactobacillus plantarum with antioxidation properties on Chinese sausages. LWT 2022, 162, 113427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strains | Starter Culture/s | Strains | Starter Culture/s |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | - | E | L. plantarum S24 + L. plantarum S91 + L. sakei S15 |

| A | L. sakei S15 | F | P. pentosaceus S128b + L. plantarum S91 + L. sakei S15 |

| B | L. plantarum S91 | G | L. sakei S15 + S. carnosus G109 |

| C | P. pentosaceus 128b | H | L. sakei S15 + L. plantarum S91 + S. carnosus G109 |

| D | L. plantarum S91 + L. sakei S15 | I | P. pentosaceus S128b + S. carnosus G109 + L. sakei S15 |

| Starter Cultures | pH | aw | TBARS (mg MDA/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 5.53 ± 0.24 a | 0.899 ± 0.00 a | 0.75 ± 0.18 a |

| A | 4.89 ± 0.29 b | 0.897 ± 0.01 a | 0.53 ± 0.19 a |

| B | 4.67 ± 0.18 c | 0.899 ± 0.00 a | 0.60 ± 0.37 a |

| C | 4.86 ± 0.26 b | 0.901 ± 0.01 a | 0.88 ± 0.57 a |

| D | 4.65 ± 0.13 c | 0.898 ± 0.00 a | 0.64 ± 0.35 a |

| E | 4.64 ± 0.18 c | 0.902 ± 0.01 a | 0.63 ± 0.31 a |

| F | 4.63 ± 0.17 c | 0.902 ± 0.00 a | 0.64 ± 0.22 a |

| G | 4.88 ± 0.27 b | 0.905 ± 0.01 a | 0.70 ± 0.32 a |

| H | 4.68 ± 0.17 c | 0.897 ± 0.00 a | 0.74 ± 0.17 a |

| I | 4.85 ± 0.23 b | 0.909 ± 0.01 a | 0.78 ± 0.36 a |

| Sig. | ** | ns | ns |

| Identified Compounds | KI | RI | Control | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetaldehyde | <500 | a | 6.74 ± 1.52 d | 19.38 ± 14.93 bcd | 32.68 ± 3.69 abc | 20.72 ± 11.32 abcd | 38.07 ± 3.45 a | 35.93 ± 3.30 ab | 27.73 ± 16.11 abc | 16.08 ± 10.57 cd | 37.81 ± 4.79 a | 25.49 ± 21.01 abc | ** |

| Ethanol | 512 | a | 34.84 ± 20.50 a | 14.64 ± 9.83 b | 4.16 ± 5.47 bc | 13.12 ± 8.82 b | 5.4 ± 3.47 bc | 5.11 ± 2.49 bc | 4.59 ± 2.01 bc | 1.68 ± 1.52 c | 6.62 ± 4.21 bc | 5.15 ± 3.41 bc | ** |

| Carbon disulfide | 536 | c | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 1.87 ± 2.86 | 6.60 ± 6.96 | 0.54 ± 0.63 | 1.01 ± 1.98 | 4.54 ± 2.76 | 1.27 ± 2.01 | 1.39 ± 2.08 | 2.19 ± 1.67 | 1.11 ± 1.77 | ns |

| Allyl mercaptan | 574 | b | 30.21 ± 10.14 c | 86.21 ± 28.33 abc | 111.06 ± 35.9 ab | 59.75 ± 32.72 bc | 117.43 ± 67.38 ab | 111.69 ± 38.06 ab | 122.46 ± 58.4 ab | 78.32 ± 24.70 abc | 144.84 ± 51.17 a | 61.57 ± 23.70 bc | * |

| Hexane | 600 | a | 145.38 ± 97.23 | 172.84 ± 105.37 | 115.63 ± 32.5 | 164.95 ± 95.69 | 214.74 ± 142.76 | 114.96 ± 59.50 | 137.3 ± 74.05 | 110.25 ± 91.61 | 147.61 ± 82.99 | 119.29 ± 71.64 | ns |

| Ethyl acetate | 639 | a | 1.33 ± 1.02 | 1.30 ± 1.53 | 2.53 ± 0.28 | 2.26 ± 1.89 | 2.06 ± 1.47 | 1.16 ± 1.38 | 1.53 ± 1.11 | 1.45 ± 1.02 | 2.42 ± 0.90 | 2.74 ± 1.59 | ns |

| Acetic acid | 710 | a | 7.95 ± 3.39 e | 18.44 ± 5.24 de | 35.51 ± 11.18 bc | 19.54 ± 3.56 de | 45.85 ± 13.20 ab | 56.00 ± 15.03 a | 50.94 ± 12.01 ab | 30.34 ± 11.24 cd | 53.25 ± 2.93 a | 48.69 ± 11.40 ab | ** |

| Allyl methyl sulfide | 730 | bc | 6.17 ± 2.76 | 6.83 ± 3.55 | 7.24 ± 3.94 | 8.2 ± 5.89 | 5.63 ± 4.68 | 4.46 ± 1.72 | 6.42 ± 5.31 | 7.82 ± 4.66 | 6.02 ± 3.90 | 7.13 ± 4.03 | ns |

| 3-hydroxy-2-butanone | 779 | a | 0.65 ± 0.76 c | 0.54 ± 0.62 c | 7.05 ± 2.72 a | 3.29 ± 2.09 bc | 4.06 ± 2.03 b | 5.89 ± 2.79 ab | 4.4 ± 2.60 ab | 0.62 ± 0.42 c | 5.79 ± 1.17 ab | 0.75 ± 0.64 c | ** |

| 1-methyl-1H-pyrrole | 786 | b | 0.00 ± 00 d | 0.40 ± 0.46 bcd | 1.13 ± 0.82 ab | 0.85 ± 0.69 abc | 1.09 ± 0.45 b | 1.04 ± 0.38 ab | 1.26 ± 0.60 a | 0.00 ± 00 d | 1.35 ± 0.57 a | 0.22 ± 0.45 cd | ** |

| Toluene | 798 | a | 0.40 ± 0.47 | 0.36 ± 0.41 | 1.68 ± 1.88 | 0.68 ± 0.88 | 0.64 ± 0.43 | 0.62 ± 0.73 | 0.97 ± 0.87 | 0.90 ± 0.80 | 0.95 ± 0.74 | 2.39 ± 2.49 | ns |

| Hexanal | 849 | a | 1.95 ± 2.41 | 2.09 ± 0.93 | 1.96 ± 1.90 | 1.93 ± 1.62 | 0.43 ± 0.26 | 2.27 ± 1.62 | 1.03 ± 0.42 | 0.80 ± 0.18 | 1.49 ± 1.13 | 1.87 ± 1.51 | ns |

| Butanoic acid | 878 | b | 0.43 ± 0.51 | 1.09 ± 0.50 | 1.44 ± 0.46 | 1.00 ± 0.47 | 1.32 ± 0.71 | 1.40 ± 0.76 | 1.60 ± 0.83 | 1.38 ± 0.76 | 1.74 ± 0.71 | 1.55 ± 0.41 | ns |

| 3,3′-thiobis-1-propene | 888 | b | 15.55 ± 4.13 a | 13.14 ± 4.51 ab | 4.86 ± 1.62 c | 7.4 ± 3.06 bc | 4.94 ± 2.06 c | 4.38 ± 2.61 c | 5.44 ± 2.61 c | 18.87 ± 7.39 a | 6.51 ± 3.38 bc | 14.86 ± 9.70 a | ** |

| Propionic acid | 891 | b | 0.38 ± 0.50 c | 2.34 ± 0.91 c | 15.96 ± 5.41 a | 0.79 ± 0.69 c | 10.79 ± 7.03 ab | 7.1 ± 5.79 bc | 11.79 ± 5.68 ab | 2.69 ± 1.11 c | 13.31 ± 8.15 ab | 2.14 ± 1.13 c | ** |

| 1-hexanol | 930 | a | 0.61 ± 0.59 | 0.27 ± 0.32 | 0.44 ± 0.51 | 0.64 ± 0.78 | 0.54 ± 0.64 | 0.38 ± 0.76 | 0.78 ± 0.91 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.28 ± 0.48 | 0.44 ± 0.54 | ns |

| Butyl propionate | 939 | b | 0.40 ± 0.35 | 0.49 ± 0.19 | 0.97 ± 0.76 | 0.74 ± 1.48 | 0.38 ± 0.45 | 0.51 ± 0.62 | 0.98 ± 0.77 | 0.75 ± 0.37 | 0.81 ± 0.62 | 0.40 ± 0.47 | ns |

| α-thujen | 944 | b | 0.66 ± 0.30 bc | 0.62 ± 0.27 bc | 1.37 ± 0.27 a | 0.8 ± 0.29 bc | 1.01 ± 0.38 b | 0.79 ± 0.17 bc | 0.95 ± 0.37 bc | 0.65 ± 0.33 bc | 0.94 ± 0.41 bc | 0.60 ± 0.33 c | ** |

| Heptanal | 955 | a | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.43 ± 0.29 | 0.19 ± 0.38 | 0.17 ± 0.34 | 0.15 ± 0.30 | 0.16 ± 0.32 | 0.15 ± 0.31 | 0.35 ± 0.40 | 0.29 ± 0.33 | ns |

| α-pinene | 950 | c | 4.74 ± 3.18 b | 6.93 ± 0.61 a | 7.97 ± 0.90 a | 7.11 ± 0.69 a | 8.80 ± 1.01 a | 8.03 ± 0.50 a | 7.94 ± 0.83 a | 7.31 ± 0.52 a | 8.46 ± 0.89 a | 7.04 ± 0.83 a | ** |

| Methyl-2-propenyl disulfide | 954 | b | 12.48 ± 4.47 ab | 9.33 ± 3.71 b | 2.59 ± 2.21 c | 8.86 ± 4.76 b | 1.33 ± 0.84 c | 0.96 ± 0.76 c | 1.28 ± 0.65 c | 14.68 ± 5.24 a | 1.80 ± 1.09 c | 10.83 ± 5.48 ab | ** |

| Camphene | 970 | c | 0.29 ± 0.19 | 0.41 ± 0.04 | 0.36 ± 0.19 | 0.41 ± 0.10 | 0.51 ± 0.08 | 0.45 ± 0.03 | 0.49 ± 0.08 | 0.29 ± 0.20 | 0.40 ± 0.27 | 0.24 ± 0.28 | ns |

| β-pinene | 996 | b | 12.01 ± 1.34 | 9.84 ± 6.61 | 10.14 ± 6.84 | 13.77 ± 2.52 | 14.63 ± 2.34 | 8.03 ± 9.28 | 20.92 ± 22.81 | 19.38 ± 5.47 | 18.19 ± 3.24 | 15.59 ± 1.23 | ns |

| β-myrcene | 998 | b | 16.67 ± 4.89 | 19.50 ± 17.93 | 41.22 ± 4.05 | 23.48 ± 11.9 | 35.43 ± 15.22 | 36.52 ± 8.87 | 25.70 ± 23.31 | 9.66 ± 11.77 | 34.98 ± 15.25 | 20.81 ± 10.08 | ns |

| 2-pentyl-furan | 1021 | b | 0.11 ± 0.21 | 0.29 ± 0.33 | 0.46 ± 0.17 | 0.39 ± 0.33 | 0.27 ± 0.34 | 1.03 ± 0.64 | 0.50 ± 0.14 | 1.14 ± 0.66 | 1.35 ± 1.57 | 1.21 ± 0.64 | ns |

| α-phellandrene | 1024 | b | 7.11 ± 1.65 c | 7.94 ± 2.51 bc | 13.60 ± 2.72 ab | 10.09 ± 4.47 abc | 15.41 ± 5.48 a | 13.41 ± 3.12 ab | 15.00 ± 5.06 a | 8.84 ± 2.61 bc | 15.56 ± 4.27 a | 9.23 ± 2.53 bc | ** |

| 3-carene | 1026 | b | 39.48 ± 3.96 e | 41.95 ± 5.34 de | 51.73 ± 1.78 bc | 46.54 ± 7.56 cd | 60.93 ± 6.97 a | 56.69 ± 4.21 ab | 56.48 ± 6.34 ab | 47.79 ± 3.78 cd | 59.63 ± 5.13 a | 47.07 ± 5.33 cd | ** |

| 6-methyl-5-hepten-2-one | 1048 | b,c | 0.18 ± 0.21 | 0.18 ± 0.21 | 0.33 ± 0.28 | 0.31 ± 0.38 | 0.38 ± 0.31 | 0.43 ± 0.34 | 0.30 ± 0.35 | 0.20 ± 0.23 | 0.13 ± 0.26 | 0.23 ± 0.27 | ns |

| α-terpinene | 1049 | b | 1.79 ± 0.29 d | 1.91 ± 0.51 cd | 2.53 ± 1.28 abcd | 2.42 ± 0.78 bcd | 3.88 ± 1.18 a | 3.27 ± 0.73 abc | 3.65 ± 1.15 ab | 2.06 ± 0.70 cd | 3.57 ± 1.09 ab | 1.99 ± 0.79 cd | ** |

| Octanal | 1051 | a | 0.78 ± 0.21 bc | 0.43 ± 0.51 c | 1.56 ± 0.19 ab | 1.09 ± 0.52 abc | 1.52 ± 0.62 ab | 1.11 ± 0.84 abc | 0.99 ± 0.77 abc | 0.63 ± 0.44 c | 1.78 ± 0.54 a | 0.92 ± 0.34 abc | * |

| D-limonene | 1054 | b | 58.72 ± 13.34 b | 60.71 ± 17.37 b | 91.14 ± 48.40 ab | 72.84 ± 28.04 ab | 108.18 ± 31.58 a | 92.09 ± 14.64 ab | 102.97 ± 28.8 a | 66.74 ± 20.43 ab | 104.22 ± 30.90 a | 67.02 ± 21.68 ab | * |

| β-phellandrene | 1060 | b | 0.73 ± 0.36 b | 0.84 ± 0.44 b | 2.62 ± 1.43 a | 0.96 ± 0.66 b | 1.14 ± 0.47 b | 1.28 ± 0.55 b | 1.28 ± 0.67 b | 1.19 ± 0.46 b | 1.55 ± 0.70 b | 1.27 ± 0.58 b | * |

| 1-methyl-2-(1-methylethyl)-benzene | 1072 | c | 65.32 ± 10.16 | 65.6 ± 13.97 | 87.8 ± 15.47 | 67.95 ± 20.45 | 103.19 ± 32.9 | 86.81 ± 27 | 99.21 ± 30.45 | 68.64 ± 21.53 | 99.41 ± 40.03 | 68.2 ± 29.09 | ns |

| Eucalyptol | 1075 | c | 1.73 ± 0.18 | 1.88 ± 0.50 | 2.43 ± 1.30 | 2.17 ± 0.52 | 1.99 ± 1.21 | 2.17 ± 0.85 | 2.18 ± 1.44 | 1.67 ± 0.45 | 2.43 ± 0.95 | 2.21 ± 0.5 | ns |

| γ-terpinene | 1089 | c | 38.89 ± 10.21 | 43.51 ± 14.32 | 58.47 ± 24.96 | 54 ± 20.51 | 81.28 ± 28.70 | 68.82 ± 23.28 | 78.78 ± 27.77 | 52.14 ± 15.34 | 81.25 ± 21.92 | 53.93 ± 10.62 | ns |

| Undecane | 1100 | a | 0.52 ± 0.23 | 0.55 ± 0.42 | 0.57 ± 0.09 | 0.71 ± 0.37 | 0.62 ± 0.44 | 0.58 ± 0.19 | 0.78 ± 0.24 | 0.44 ± 0.25 | 0.59 ± 0.18 | 0.27 ± 0.18 | ns |

| 2-carene | 1120 | c | 0.77 ± 0.61 | 0.83 ± 0.70 | 1.05 ± 0.80 | 1.17 ± 0.48 | 0.83 ± 1.10 | 0.93 ± 1.08 | 1.36 ± 0.92 | 0.17 ± 0.34 | 0.95 ± 1.13 | 0.42 ± 0.51 | ns |

| Terpinolene | 1131 | b | 1.99 ± 0.51 | 2.32 ± 1.15 | 3.8 ± 0.78 | 2.85 ± 1.23 | 4.07 ± 1.78 | 3.32 ± 0.85 | 4.10 ± 1.50 | 2.62 ± 1.01 | 4.01 ± 1.43 | 2.62 ± 0.88 | ns |

| Propyl hexanoate | 1134 | b | 2.16 ± 0.26 | 0.95 ± 0.21 | 2.86 ± 0.54 | 2.41 ± 3.65 | 1.08 ± 1.03 | 1.49 ± 1.78 | 1.97 ± 2.40 | 0.76 ± 0.99 | 2.21 ± 1.79 | 0.33 ± 0.24 | ns |

| Benzyl alcohol | 1135 | c | 0.73 ± 0.36 | 1.3 ± 0.91 | 0.85 ± 0.77 | 1.54 ± 0.22 | 1.59 ± 0.70 | 0.7 ± 0.82 | 0.95 ± 0.79 | 0.99 ± 1.25 | 0.74 ± 0.88 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | ns |

| 1-methyl-4-(1-methylethenyl)-benzene | 1136 | c | 3.36 ± 0.42 bc | 3.67 ± 0.44 bc | 4.79 ± 2.52 abc | 2.91 ± 0.44 c | 4.77 ± 0.81 abc | 6.27 ± 0.85 a | 6.09 ± 1.90 a | 4.72 ± 0.65 abc | 6.73 ± 1.82 a | 5.42 ± 0.89 ab | ** |

| Diallyl disulfide | 1038 | a | 68.56 ± 24.79 ab | 50.93 ± 24.11 abc | 13.75 ± 4.95 d | 43.81 ± 22.92 bcd | 20.29 ± 10.72 cd | 16.71 ± 13.25 cd | 21.46 ± 9.75 cd | 83.74 ± 38.10 a | 25.96 ± 13.52 cd | 68.34 ± 34.93 ab | ** |

| 2-nonanone | 1140 | c | 0.00 ± 0.00 c | 2.62 ± 2.05 a | 0.43 ± 0.50 bc | 0.00 ± 0.00 c | 0.62 ± 0.54 bc | 0.65 ± 0.76 bc | 0.83 ± 0.97 bc | 0.49 ± 0.97 bc | 1.60 ± 1.02 ab | 0.57 ± 0.67 bc | * |

| Linalool | 1161 | a | 3.67 ± 0.35 c | 3.62 ± 0.75 c | 3.79 ± 1.89 c | 4.22 ± 1.09 bc | 5.70 ± 1.33 ab | 5.18 ± 0.89 abc | 5.64 ± 1.25 abc | 4.4 ± 1.01 bc | 6.22 ± 1.26 a | 4.51 ± 0.74 bc | * |

| di-2-propenyl disulfide | 1168 | c | 7.61 ± 2.15 abcd | 7.72 ± 1.99 abcd | 3.25 ± 2.23 d | 8.19 ± 4.49 bc | 5.89 ± 2.48 cd | 5.13 ± 2.32 cd | 6.30 ± 2.19 bcd | 10.73 ± 3.40 ab | 8.15 ± 3.09 bc | 11.58 ± 4.03 a | * |

| 6-methyl-3,5-heptadiene-2-one | 1175 | c | 0.51 ± 0.38 bc | 0.55 ± 0.39 bc | 1.09 ± 0.83 abc | 0.22 ± 0.30 c | 1.36 ± 0.38 ab | 0.89 ± 0.60 abc | 0.35 ± 0.70 c | 0.35 ± 0.43 c | 1.58 ± 1.10 a | 0.90 ± 0.15 abc | * |

| 4-methyl-phenol | 1184 | c | 0.17 ± 0.34 bc | 0.28 ± 0.33 abc | 0.00 ± 0.00 c | 0.14 ± 0.27 bc | 0.49 ± 0.34 ab | 0.39 ± 0.53 abc | 0.00 ± 0.00 c | 0.00 ± 0.00 c | 0.67 ± 0.25 a | 0.00 ± 0.00 c | * |

| Dodecane | 1200 | c | 0.69 ± 0.30 | 0.32 ± 0.37 | 0.52 ± 0.39 | 0.82 ± 0.65 | 0.98 ± 0.47 | 0.76 ± 0.56 | 0.53 ± 0.36 | 0.66 ± 0.46 | 1.06 ± 0.15 | 0.98 ± 0.27 | ns |

| Benzeneethanol | 1214 | c | 0.00 ± 0.00 c | 0.00 ± 0.00 c | 00.00 ± 0.00 c | 0.21 ± 0.42 bc | 0.00 ± 0.00 c | 0.00 ± 0.00 c | 0.32 ± 0.64 bc | 0.92 ± 0.30 a | 0.65 ± 0.46 ab | 0.79 ± 0.17 a | ** |

| Hexyl butanoate | 1221 | b | 4.30 ± 1.50 | 1.61 ± 0.60 | 2.68 ± 1.43 | 4.94 ± 3.52 | 2.72 ± 0.43 | 3.12 ± 1.63 | 3.56 ± 1.46 | 2.27 ± 0.68 | 3.98 ± 1.55 | 2.17 ± 0.46 | ns |

| p-Menth-2-ene-1,8-diol | 1228 | c | 0.39 ± 0.33 | 0.38 ± 0.09 | 0.47 ± 0.10 | 0.37 ± 0.27 | 0.12 ± 0.23 | 0.19 ± 0.21 | 0.60 ± 0.11 | 0.18 ± 0.35 | 0.58 ± 0.39 | 0.36 ± 0.41 | ns |

| Terpinene-4-ol | 1233 | b,c | 2.16 ± 0.24 cd | 1.50 ± 1.00 d | 2.63 ± 1.67 bcd | 2.26 ± 0.54 cd | 2.99 ± 0.47 bc | 3.25 ± 0.18 abc | 3.79 ± 0.68 ab | 2.42 ± 0.44 cd | 4.18 ± 0.38 a | 2.64 ± 0.31 bcd | ** |

| Phenol | 1249 | c | 0.34 ± 0.41 | 0.17 ± 0.34 | 0.34 ± 0.28 | 0.24 ± 0.30 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.15 ± 0.30 | 0.24 ± 0.47 | 0.20 ± 0.26 | 0.13 ± 0.26 | 0.14 ± 0.17 | ns |

| Decanal | 1258 | a | 1.00 ± 1.02 bc | 0.44 ± 0.69 c | 2.14 ± 0.15 a | 1.55 ± 0.54 ab | 0.26 ± 0.31 c | 0.33 ± 0.65 c | 0.49 ± 0.73 c | 0.41 ± 0.09 c | 0.31 ± 0.61 c | 1.85 ± 1.24 ab | ** |

| α-terpineol | 1264 | b,c | 2.11 ± 0.13 cde | 0.95 ± 1.09 e | 2.85 ± 1.60 abcd | 1.95 ± 0.46 de | 3.23 ± 0.54 abc | 3.56 ± 0.40 ab | 3.47 ± 0.45 ab | 1.76 ± 1.23 e | 3.88 ± 0.66 a | 2.43 ± 0.23 bcd | ** |

| Benzoic acid 2-hydroxy-methyl ester | 1273 | c | 0.37 ± 0.43 bc | 0.64 ± 0.10 abc | 1.08 ± 0.40 a | 0.21 ± 0.43 c | 0.25 ± 0.29 c | 0.31 ± 0.38 bc | 0.62 ± 0.13 abc | 0.6 ± 0.45 abc | 0.82 ± 0.11 ab | 0.93 ± 0.11 a | ** |

| 3-phenyl-2-methyl-propanal | 1332 | b,c | 340.98 ± 94.79 bc | 409.94 ± 45.27 ab | 83.13 ± 35.79 d | 311.77 ± 124.86 c | 83.17 ± 10.07 d | 63.6 ± 33.26 d | 83.06 ± 8.22 d | 437.41 ± 63.67 a | 124.35 ± 22.1 d | 462.28 ± 73.41 a | ** |

| Camphene | 1362 | c | 5.37 ± 0.36 b | 5.35 ± 0.47 b | 14.59 ± 10.28 a | 4.33 ± 1.98 b | 5.48 ± 1.75 b | 7.17 ± 3.22 b | 7.55 ± 2.08 b | 4.64 ± 1.31 b | 5.10 ± 5.93 b | 4.38 ± 0.45 b | * |

| 3-carvomenthenone | 1364 | c | 1.54 ± 1.07 | 1.15 ± 0.49 | 2.33 ± 2.87 | 0.58 ± 0.44 | 1.2 ± 0.95 | 1.62 ± 3.25 | 2.4 ± 2.85 | 2.08 ± 1.83 | 3.38 ± 4.01 | 2.83 ± 0.35 | ns |

| Phellandral | 1368 | c | 2.99 ± 2.04 abcd | 3.64 ± 0.56 abc | 1.73 ± 1.43 d | 2.47 ± 1.06 bcd | 1.97 ± 0.46 cd | 2.97 ± 1.42 abcd | 2.9 ± 0.68 abcd | 3.71 ± 0.55 abc | 4.15 ± 1.04 ab | 4.48 ± 0.52 a | * |

| δ-elemene | 1371 | c | 2.65 ± 0.78 | 2.88 ± 2.56 | 2.81 ± 2.42 | 2.83 ± 1.30 | 4.15 ± 0.40 | 5.16 ± 1.01 | 5.12 ± 1.98 | 4.58 ± 2.22 | 5.28 ± 0.84 | 3.86 ± 0.45 | ns |

| α-hydroxyphenylacetic acid | 1376 | c | 2.38 ± 0.81 | 3.27 ± 2.86 | 0.66 ± 0.68 | 2.49 ± 1.15 | 1.30 ± 0.91 | 1.00 ± 1.29 | 1.23 ± 0.82 | 5.30 ± 6.04 | 2.51 ± 0.76 | 4.46 ± 0.56 | ns |

| 4-(1-methylethyl) benzenemethanol | 1380 | b | 76.73 ± 24.88 bc | 101.73 ± 15.98 ab | 56.92 ± 28.91 c | 73.05 ± 29.62 bc | 60.28 ± 14.06 c | 69.13 ± 24.02 bc | 69.98 ± 10.95 bc | 92.40 ± 41.13 bc | 90.30 ± 20.85 bc | 129.31 ± 13.77 a | ** |

| 3-methyl-4-isopropylphenol | 1392 | c | 17.19 ± 5.94 | 22.93 ± 3.09 | 19.00 ± 10.19 | 16.58 ± 7.26 | 18.85 ± 3.50 | 22.80± 5.02 | 22.46 ± 1.75 | 20.36 ± 12.25 | 28.82 ± 5.26 | 31.52 ± 2.09 | ns |

| Copaene | 1432 | b | 4.92 ± 0.86 | 6.93 ± 1.66 | 4.32 ± 4.67 | 5.17 ± 1.94 | 6.00 ± 0.97 | 7.80 ± 1.14 | 8.09 ± 2.39 | 7.81 ± 1.96 | 8.20 ± 1.41 | 7.95 ± 0.44 | ns |

| β-elemene | 1438 | c | 0.81 ± 1.17 | 0.36 ± 0.72 | 2.08 ± 3.27 | 0.29 ± 0.34 | 0.36 ± 0.42 | 1.17 ± 1.44 | 0.26 ± 0.52 | 0.27 ± 0.53 | 0.90 ± 1.04 | 0.95 ± 1.10 | ns |

| Caryophyllene | 1489 | b,c | 21.15 ± 4.28 c | 25.92 ± 4.00 bc | 24.92 ± 12.31 bc | 28.22 ± 12.93 bc | 33.48 ± 4.11 ab | 34.75 ± 7.89 ab | 35.66 ± 7.34 ab | 30.52 ± 3.67 abc | 40.73 ± 5.53 a | 33.36 ± 1.06 ab | * |

| α-caryophyllene | 1492 | c | 1.48 ± 0.48 | 1.89 ± 0.50 | 1.29 ± 0.76 | 1.62 ± 0.90 | 2.04 ± 0.25 | 2.10 ± 0.73 | 2.44 ± 0.73 | 6.47 ± 7.96 | 2.39 ± 0.39 | 2.54 ± 0.15 | ns |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kaya, M.; Sayın, B.; Çinar Topçu, K.; Kaban, G. Effects of Autochthonous Starter Cultures on the Quality Characteristics of Traditionally Produced Sucuk. Fermentation 2025, 11, 672. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120672

Kaya M, Sayın B, Çinar Topçu K, Kaban G. Effects of Autochthonous Starter Cultures on the Quality Characteristics of Traditionally Produced Sucuk. Fermentation. 2025; 11(12):672. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120672

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaya, Mükerrem, Bilge Sayın, Kübra Çinar Topçu, and Güzin Kaban. 2025. "Effects of Autochthonous Starter Cultures on the Quality Characteristics of Traditionally Produced Sucuk" Fermentation 11, no. 12: 672. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120672

APA StyleKaya, M., Sayın, B., Çinar Topçu, K., & Kaban, G. (2025). Effects of Autochthonous Starter Cultures on the Quality Characteristics of Traditionally Produced Sucuk. Fermentation, 11(12), 672. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11120672