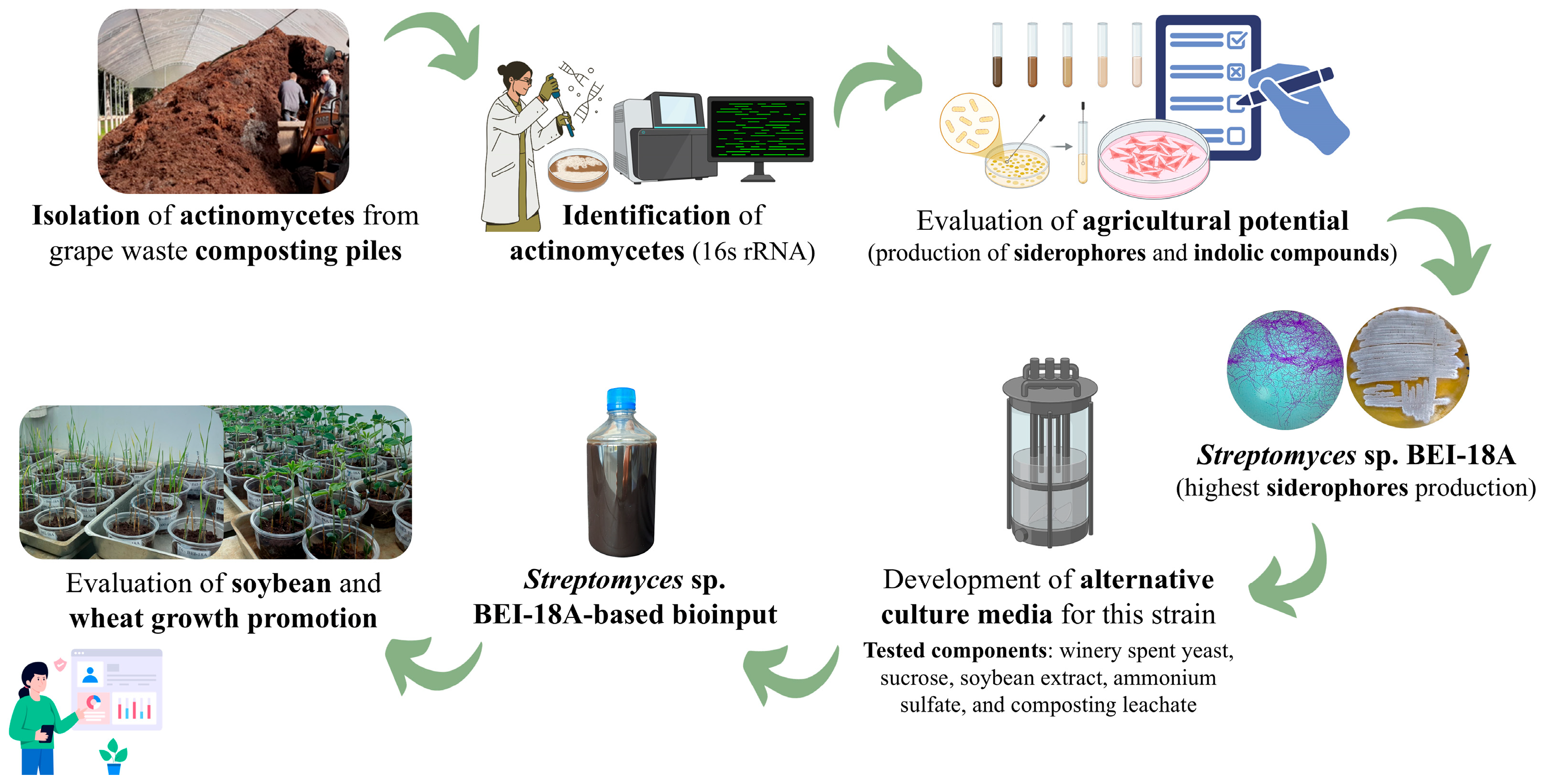

From Isolation to Plant Growth Evaluation: Development of a Streptomyces-Based Bioinput Using Spent Yeast and Composting Leachate

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolation and Identification of Actinomycetes

2.2. Microbial Screening Based on Agricultural Potential

2.3. Development of Alternative Culture Medium and Bioinput Production

- (a)

- Determination of ACM formulation (Step I): The first stage focused on identifying the optimal ACM formulation for the growth of the selected actinomycete using a mixture design. The components evaluated included spent yeast (SY), sucrose (SC), soybean extract (SE), and ammonium sulfate (AS). Each formulation contained 12 g/L (m/v) of these components dissolved in deionized water. The primary objective was to assess the feasibility of SY as a constituent of the ACM. SY, a semi-solid residue derived from the wine clarification process, was supplied by a company in the Serra Gaúcha region, Brazil. Prior to use, SY was centrifuged (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany, Centrifuge 5810) at 3500 rpm for 10 min to separate the solid fraction. The remaining components (SE, SC, and AS) were obtained from local suppliers.

- (b)

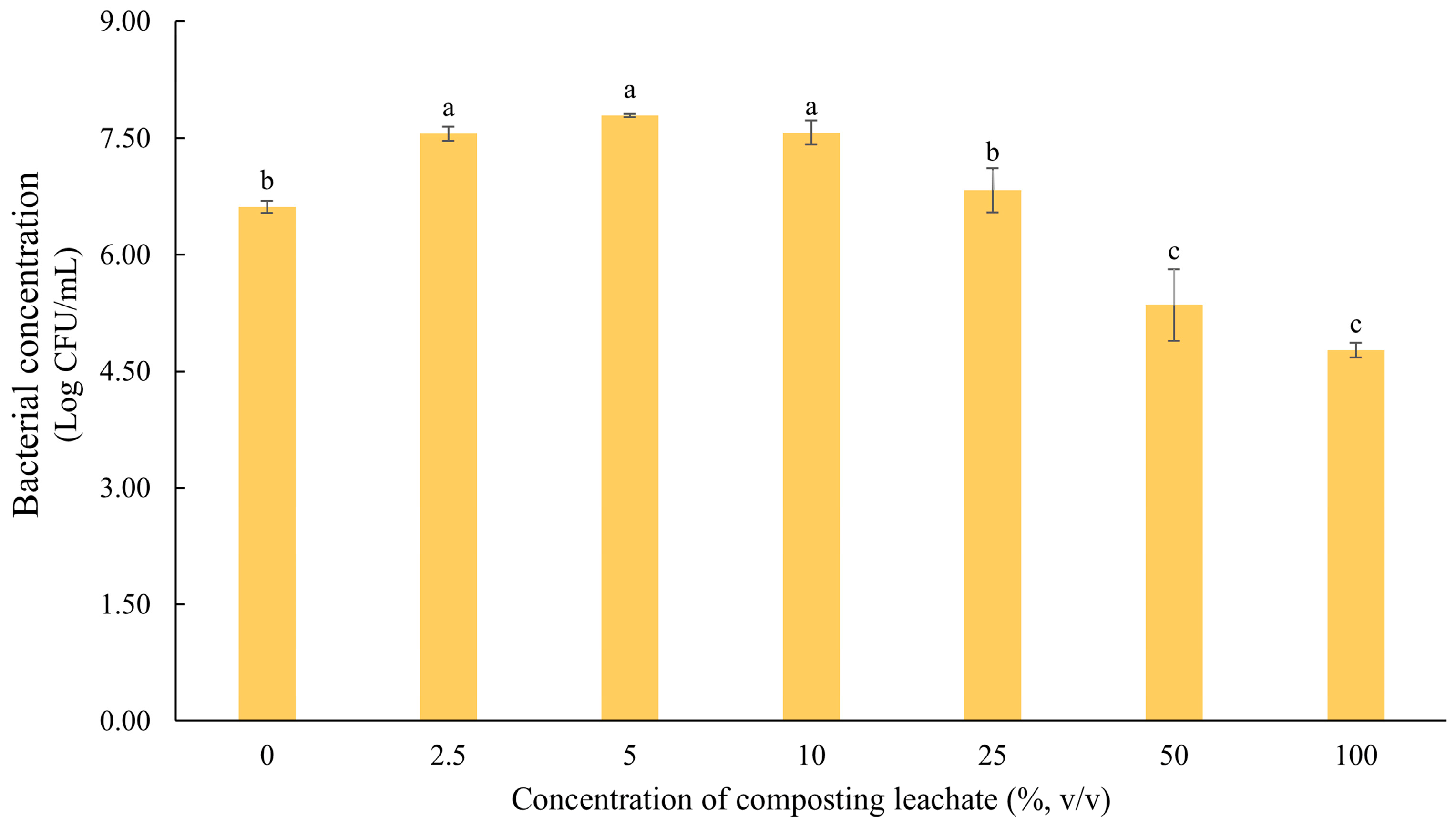

- Incorporation of composting leachate (CL) (Step II): Based on the optimal formulation identified in Step I, the second stage aimed to incorporate composting leachate (CL) into the ACM. This step sought to evaluate CL as an alternative to potable water in microbial cultivation while providing a sustainable disposal route for this effluent. CL was tested at concentrations of 0%, 2.5%, 5%, 10%, 25%, 50%, and 100% (v/v) to determine the maximum level tolerated without impairing microbial growth. The CL used in this study corresponded to the liquid fraction derived from composting piles of grape-processing residues and by-products. Samples were collected from four composting piles with maturation times ranging from 1 to 4 years. The composting process was conducted by Beifiur LTDA (Garibaldi, Brazil), which also supplied the CL.

- (c)

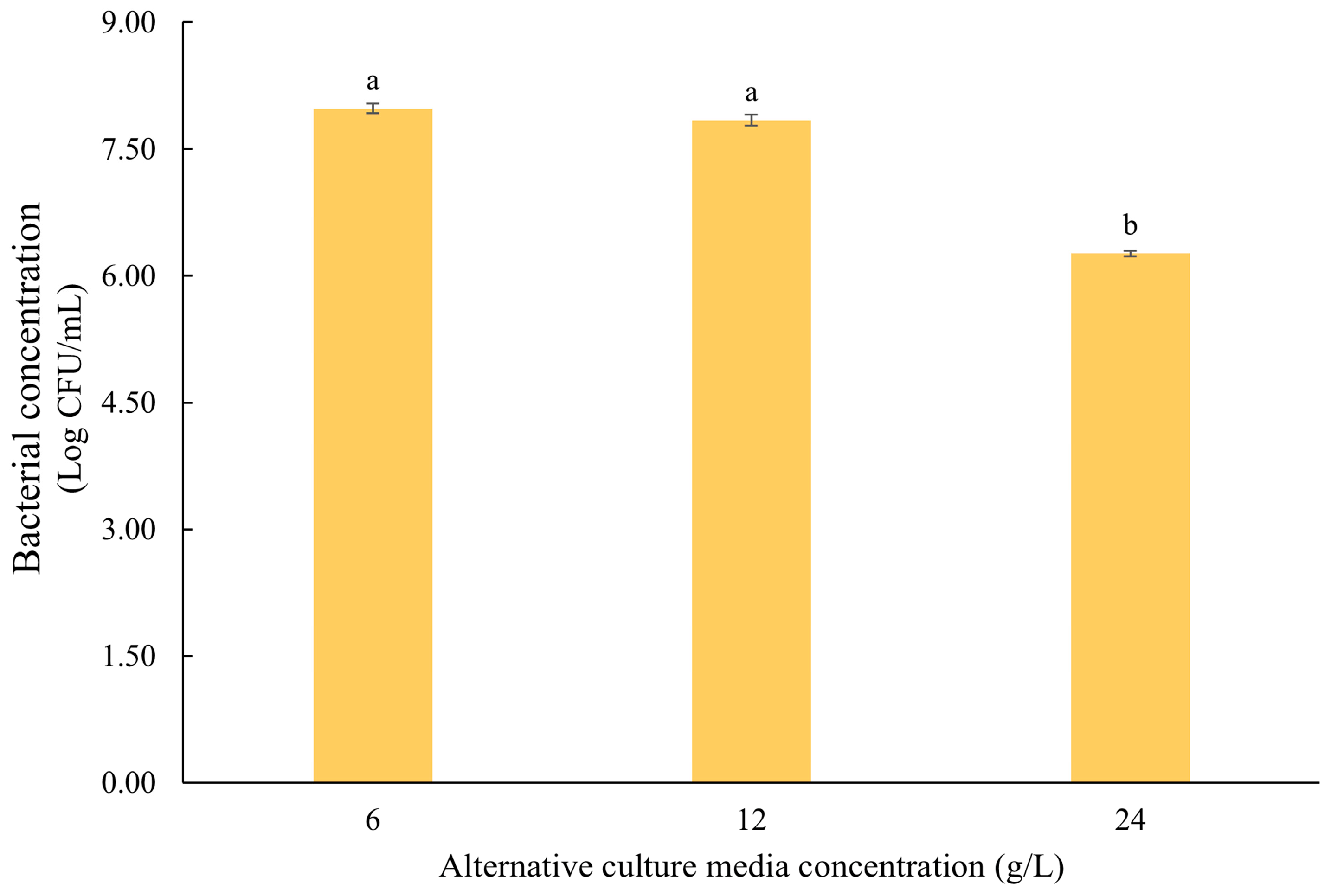

- Optimization of ACM component concentrations (Step III): In the final stage, the concentrations of ACM components (based on Step I) were optimized considering the CL concentration determined in Step II. Fermentation was performed using ACM formulations containing the standard concentration (12 g/L; from Step I), half (6 g/L), and double (24 g/L). This step aimed to determine whether bacterial growth could be enhanced by adjusting the nutrient concentration.

2.4. Evaluation of the Plant Growth-Promoting Capacity of the Bioinput

2.5. Data Treatment

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Identification of Isolates and Evaluation of Their Agricultural Potential In Vitro

3.2. Development of the Alternative Culture Medium (ACM)

3.3. Plant Growth Promotion by Thef Streptomyces sp. BEI-18A-Based Bioinput

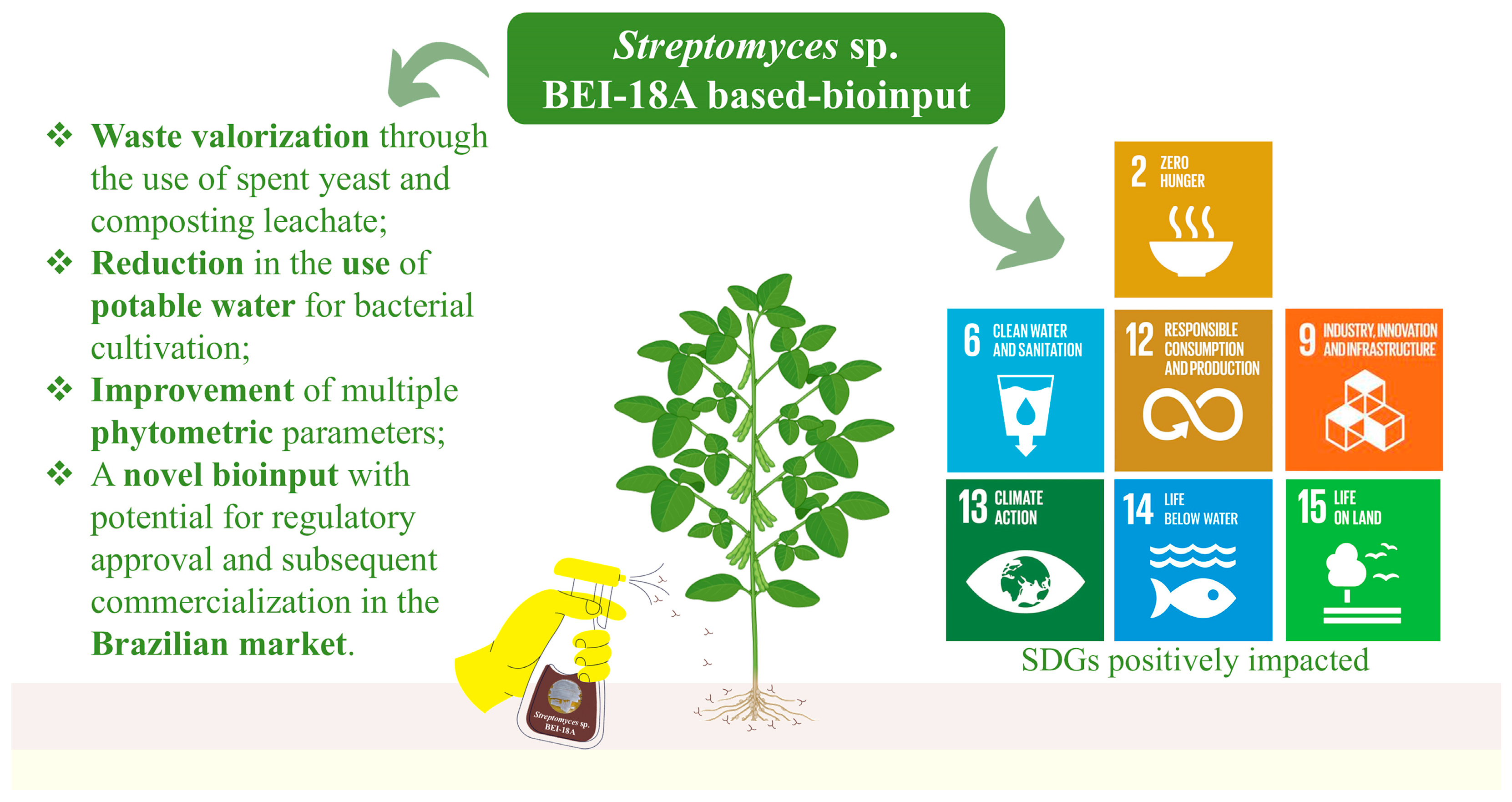

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McGuirre, A.V.; Northfield, T.D. Tropical occurrence and agricultural importance of Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium anisopliae. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, J.B.S.; Neto, V.P.C.; Sousa, C.D.A.; Filho, M.R.C.; Rodrigues, A.C.; Bonifacio, A. Trichoderma and bradyrhizobia act synergistically and enhance the growth rate, biomass and photosynthetic pigments of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) grown in controlled conditions. Symbiosis 2020, 80, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaniyan, O.T.; Adetunji, C.O. Biochemical role of beneficial microorganisms: An overview on recent development in environmental and agro science. In Microbial Rejuvenation of Polluted Environment; Adetunji, C.O., Panpatte, D.G., Jhala, Y.K., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Senger, M.; Valencia, S.U.; Nazari, M.T.; Vey, R.T.; Piccin, J.S.; Martin, T.N. Evaluation of Trichoderma aspereloides-based inoculant as growth promoter of soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.): A field-scale study in Brazil. J. Crop Sci. Biotechnol. 2022, 26, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrofit. Phytosanitary Pesticide System. 2025. Available online: https://agrofit.agricultura.gov.br/agrofit_cons/principal_agrofit_cons (accessed on 15 September 2025). (In Portuguese)

- Brasil. Bioinputs, Version 3.0.6. 2025. Available online: https://www.gov.br/agricultura/pt-br/assuntos/inovacao/bioinsumos/o-programa/catalogo-nacional-de-bioinsumos (accessed on 15 September 2025). (In Portuguese)

- Nazari, M.T.; Machado, B.S.; Marchezi, G.; Crestani, L.; Ferrari, V.; Colla, L.M.; Piccin, J.S. Use of soil actinomycetes for pharmaceutical, food, agricultural, and environmental purposes. 3 Biotech 2022, 12, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barka, E.A.; Vetsa, P.; Sanchez, L.; Gaveau-Vaillant, N.; Jacquard, C.; Klenk, H.-P.; Clément, C.; Ouhdouch, Y.; Van Wezel, G.P. Taxonomy, physiology, and natural products of actinobacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2015, 80, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelmohsen, U.R.; Grkovic, T.; Balasubramanian, S.; Kamel, M.S.; Quinn, R.J.; Hentschel, U. Elicitation of secondary metabolism in actinomycetes. Biotechnol. Adv. 2015, 33, 798–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, A.A.; Haq, S.; Bhat, R.A. Actinomycetes benefaction role in soil and plant health. Microb. Pathog. 2017, 111, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Guo, L.-N.; Li, S.-H.; Wu, W.; Ding, J.W.; Xu, H.-J.; Luo, C.-B.; Li, J.; Li, D.-Q.; Liu, Z.-Q. Biodegradation mechanism of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin in bacteria-dominant aerobic composting from agricultural biomass waste: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2025, 11, 100879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oumaima, B.; Nour-Eddine, C.; Mohammed, R.S.; Ouammou, A.; Oussama, C.; Faouzi, E. Thermoactinomyces sacchari competent strain: Isolation from compost, selection and characterization for biotechnological use. Sci. Afr. 2024, 23, e02121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Guo, X.; Deng, H.; Dong, D.; Tu, Q.; Wu, W. New insights into the structure and dynamics of actinomycetal community during manure composting. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 3327–3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, Y.; Wang, H.; Lu, Q.; Wei, Z. Effect of thermotolerant actinomycetes inoculation on cellulose degradation and the formation of humic substances during composting. Waste Manag. 2017, 68, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Choi, J.Y.; Park, D.H.; Je, Y.H. Potential of secondary metabolites from soil-derived actinomycetes as juvenile hormone disruptor and insecticides. J. Asia-Pac. Entomol. 2024, 27, 102279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schniete, J.K.; Fernández-Martínez, L.T. Natural product discovery in soil actinomycetes: Unlocking their potential within an ecological context. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2024, 79, 102487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gowrisudha, R.R.; Vetrivelkalai, P.; Anita, B.; Manoranjitham, S.K.; Sankari, A.; Kavitha, P.G.; Devrajan, K. A new frontier in biological defense; plant microbiome as a shield against root feeding nematodes and leverage of crop health. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2025, 138, 102681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decesaro, A.; Machado, T.S.; Cappellaro, A.C.; Rempel, A.; Margarites, A.C.; Reinehr, C.O.; Eberlin, M.N.; Zampieri, D.; Thomé, A.; Colla, L.M. Biosurfactants production using permeate from whey ultrafiltration and bioproduct recovery by membrane separation process. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2020, 23, 539–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, K.A.; Bataus, L.A.M.; Campos, I.T.N.; Fernandes, K.F. Development of culture medium using extruded bean as a nitrogen source for yeast growth. J. Microbiol. Methods 2013, 92, 310–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contreras, M.D.M.; Romero-García, J.M.; López-Linares, J.C.; Romero, I.; Castro, E. Residues from grapevine and wine production as feedstock for a biorefinery. Food Bioprod. Process. 2022, 134, 56–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Iseppi, A.; Lomolino, G.; Marangon, M.; Curioni, A. Current and future strategies for wine yeast lees valorization. Food Res. Int. 2020, 137, 109352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, V.; Taffarel, S.R.; Espinosa-Fuentes, E.; Oliveira, M.L.S.; Saikia, B.K.; Oliveira, L.F.S. Chemical evaluation of by-products of the grape industry as potential agricultural fertilizers. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 208, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, T.; Chowdhary, P.; Chaurasia, D.; Gnansounou, E.; Pandey, A.; Chaturvedi, P. Sustainable green processing of grape pomace for the production of value-added products: An overview. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 23, 101592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanakis, C.M. Handbook of Grape Processing By-Products; Academic Press: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Badillo, T.P.S.; Pham, T.T.H.; Nadeau, M.; Allard-Massicotte, R.; Jacob-Vaillancourt, C.; Heitz, M.; Ramirez, A.A. Production of plant growth–promoting bacteria inoculants from composting leachate to develop durable agricultural ecosystems. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 29037–29045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, A.; Chen, S.; Qian, G.; Xu, Z.P. Optimization of fermentative biohydrogen production by response surface methodology using fresh leachate as nutrient supplement. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 8661–8668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ming, L.; Xuya, P.; Youcai, Z.; Wenchuan, D.; Huashuai, C.; Guotao, L.; Zhengsong, W. Microbial inoculum with leachate recirculated cultivation for the enhancement of OFMSW composting. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 153, 885–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermelho, A.B.; Macrae, A.; Neves, A., Jr.; Domingos, L.; De Souza, J.E.; Borsari, A.C.P.; De Oliveira, S.S.; Von Der Weid, I.; Veillard, P.; Zilli, J.E. Microbial bioinputs in Brazilian agriculture. J. Integr. Agric. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambrook, J.; Russel, D.W. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 3rd ed.; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Granada, C.E.; Beneduzi, A.; Lisboa, B.B.; Turchetto-Zolet, A.C.; Vargas, L.K.; Passaglia, L.M. Multilocus sequence analysis reveals taxonomic differences among Bradyrhizobium sp. symbionts of Lupinus albescens plants growing in arenized and non-arenized areas. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2015, 38, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NCBI. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ (accessed on 14 November 2022).

- Schwyn, B.; Neilands, J.B. Universal chemical assay for the detection and determination of siderophores. Anal. Biochem. 1986, 160, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glickmann, E.; Dessaux, Y. A critical examination of the specificity of the Salkowski Reagent for indolic compounds produced by phytopathogenic bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995, 61, 793–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Food Supply. Manual of Official Analytical Methods for Fertilizers and Amendments; MAPA: Brasília, Brazil, 2017.

- Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Food Supply. Normative Instruction SDA Number 30, 11/12/2010; MAPA: Brasília, Brazil, 2010.

- Dickson, A.; Leaf, A.L.; Hosner, J.F. Quality appraisal of white spruce and white pine seedling stock in nurseries. For. Chron. 1960, 36, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoyalp, Z.S.; Temel, A.; Erdogan, B.R. Iron in infectious diseases friend or foe?: The role of gut microbiota. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2023, 75, 127093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benite, A.M.C.; Machado, S.P.; Machado, B.C. Siderophores: “A response from microorganisms”. Quím. Nova 2002, 25, 1155–1164. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armin, R.; Zuhlke, S.; Grunewaldt-Stocker, G.; Mahnkopp-Dirks, F.; Kusari, S. Production of Siderophores by an Apple Root-Associated Streptomyces ciscaucasicus Strain GS2 Using Chemical and Biological OSMAC Approaches. Molecules 2021, 26, 3517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasheii, B.; Mahmoodi, P.; Mohammadzadeh, A. Siderophores: Importance in bacterial pathogenesis and applications in medicine and industry. Microbiol. Res. 2021, 250, 126790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehinmitan, E.; Losenge, T.; Mamati, E.; Ngumi, V.; Juma, P.; Siamalube, B. BioSolutions for Green Agriculture: Unveiling the diverse roles of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria. Int. J. Microbiol. 2024, 2024, 6181491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rungin, S.; Indananda, C.; Suttiviriya, P.; Kruasuwan, W.; Jaemsaeng, R.; Thamchaipenet, A. Plant growth enhancing effects by a siderophore-producing endophytic streptomycete isolated from a Thai jasmine rice plant (Oryza sativa L. cv. KDML105). Antonie Leeuwenhoek 2012, 102, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deb, C.R.; Tatung, M. Siderophore producing bacteria as biocontrol agent against phytopathogens for a better environment: A review. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2024, 165, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Powers, M.; Králová, S.; Nguyen, G.-S.; Fawwal, D.V.; Degnes, K.; Lewin, A.S.; Klinkenberg, G.; Wentzel, A.; Liles, M.R. Streptomyces poriferorum sp. nov., a novel marine sponge-derived Actinobacteria species expressing anti-MRSA activity. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 44, 126244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.; Jin, B.; Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Li, Z. Utilization of winery wastes for Trichoderma viride biocontrol agent production by solid state fermentation. J. Environ. Sci. 2008, 20, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Bibbins, B.; Torrado-Agrasar, A.; Salgado, J.M.; Oliveira, R.P.S.; Domínguez, J.M. Potential of lees from wine, beer and cider manufacturing as a source of economic nutrients: An overview. Waste Manag. 2015, 40, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, M.A.; Moral, R.; Paredes, C.; Pérez-Espinosa, A.; Moreno-Caselles, J.; Pérez-Murca, M.D. Agrochemical characterisation of the solid by-products and residues from the winery and distillery industry. Waste Manag. 2008, 28, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradelo, R.; Moldes, A.B.; Barral, M.T. Evolution of organic matter during the mesophilic composting of lignocellulosic winery wastes. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 116, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, J.V.; Silva, S.C.M.; Cremasco, M.A. Evaluation of carbon:nitrogen ratio in semi-defined culture medium to tacrolimus biosynthesis by Streptomyces tsukubaensis and the effect on bacterial growth. Biotechnol. Rep. 2020, 26, e00440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Lee, M.J.; Choi, Y.E.; Chun, G.T.; Jeong, Y.S. Optimization of cultivation medium and fermentation parameters for lincomycin production by Streptomyces lincolnensis. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 2014, 19, 1014–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Zou, P.; Miao, L.; Qi, J.; Song, L.; Zhu, L.; Xu, X. Medium optimization for the production of anti-cyanobacterial substances by Streptomyces sp. HJC-D1 using response surface methodology. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 21, 5983–5990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, D.; Bora, T.C.; Bordoloi, G.N.; Mazumdar, S. Influence of nutrition and culturing conditions for optimum growth and antimicrobial metabolite production by Streptomyces sp. 201. J. Mycol. Med. 2009, 19, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, M.K.; Meena, M.; Aamir, M.; Zehra, A.; Upadhyay, R.S. Regulation and role of metal ions in secondary metabolite production by microorganisms. In New and Future Developments in Microbial Biotechnology and Bioengineering; Gupta, V.K., Pandey, A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 259–277. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, N.; Flury, M.; Hinman, C.; Cogger, C.G. Chemical and physical characteristics of compost leachates—A review. Wash. State Dep. Transp. 2013, 1–54. Available online: http://www.wsdot.wa.gov/research/reports/fullreports/819.1.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Wang, N.; Ren, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Guo, D. A preliminary study to explain how Streptomyces pactum (Act12) works on phytoextraction: Soil heavy metal extraction, seed germination, and plant growth. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Qiao, Y.; Jin, R.; Jia, M.; Liu, J.; He, Z.; Liu, Z. Application of chlorine dioxide and its disinfection mechanism. Arch. Microbiol. 2024, 206, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, M.; Nawangsih, A.A.; Wahyudi, A.T. Rhizosphere Streptomyces formulas as the biological control agent of phytopathogenic fungi Fusarium oxysporum and plant growth promoter of soybean. Biodiversitas 2021, 22, 3015–3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanke, R.; Lohr, J.; Poduschnick, L.; Tesche, S.; Fillaudeau, L.; Büchs, J.; Krull, R. Rheology and culture reproducibility of filamentous microorganisms: Impact of flow behavior and oxygen transfer during salt-enhanced cultivation of the actinomycete Actinomadura namibiensis. Eng. Life Sci. 2024, 25, e202400078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, M.H.; Van der Hoeven, J.S.; Van den Kieboom, C.W.A.; Camp, P.J.M. Effects of oxygen on the growth and metabolism of Actinomyces viscosus. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 1988, 4, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiharn, M.; Theantana, T.; Pathom-Aree, W. Evaluation of biocontrol activities of Streptomyces spp. against rice blast disease fungi. Pathogens 2020, 9, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Wang, T.; Jiang, J.; Wang, Y.; Lv, C.; Sun, K.; Sun, J.; Yan, B.; Kang, C.; Guo, L.; et al. Biological control and plant growth promotion properties of Streptomyces albidoflavus St-220 isolated from Salvia miltiorrhiza rhizosphere. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 976813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindasamy, V.; George, P.; Ramesh, S.V.; Sureshkumar, P.; Rane, J.; Minhas, P.S. Characterization of root-endophytic actinobacteria from cactus (Opuntia ficus-indica) for plant growth promoting traits. Arch. Microbiol. 2022, 204, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Kalia, A.; Sharma, S. Bioformulation of Azotobacter and Streptomyces for improved growth and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.): A field study. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2024, 43, 2555–2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Hu, L.; Jia, R.; Cao, S.; Sun, Y.; Dong, X.; Wang, Y. Streptomyces pratensis S10 Promotes Wheat Plant Growth and Induces Resistance in Wheat Seedlings against Fusarium graminearum. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripathi, P.; Subedi, S.; Khan, A.L.; Chung, Y.-S.; Kim, Y. Silicon effects on the root system of diverse crop species using root phenotyping technology. Plants 2021, 10, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Chen, L.; Gao, T. Effect of green infrastructure with different woody plant root systems on the reduction of runoff nitrogen. Water 2024, 16, 1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Sharma, A.; Malannavar, A.B.; Salwan, R. Molecular aspects of biocontrol species of Streptomyces in agricultural crops. In Molecular Aspects of Plant Beneficial Microbes in Agriculture; Sharma, V., Salwan, R., Al-Ani, L.K.T., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 89–109. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, C.-L.; Mundschenk, E.; Wilken, V.; Sensel-Gunke, K.; Ellmer, F. Biowaste digestates: Influence of pelletization on nutrient release and early plant development of oats. Waste Biomass Valor. 2018, 9, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Song, Y.; An, Y.; Lu, Y.; Zhong, G. Mechanisms and Impact of rhizosphere microbial metabolites on crop health, traits, functional components: A comprehensive review. Molecules 2024, 29, 5922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Chen, C.; Zhang, D.; Shu, B.; Xiao, J.; Xia, R. Influence of nutrient deficiency on root architecture and root hair morphology of trifoliate orange (Poncirus trifoliata L. Raf.) seedlings under sand culture. Sci. Hortic. 2013, 162, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengough, A.G. Root elongation is restricted by axial but not by radial pressures: So what happens in field soil? Plant Soil 2012, 360, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nivedita, S.; Behera, S.S.; Behera, P.K.; Parwez, Z.; Giri, S.; Behera, H.T.; Ray, L. Salt-resistant Streptomyces consortia promote growth of rice (Oryza sativa var. Swarna) alleviating salinity and drought stress tolerance by enhancing photosynthesis, antioxidant function, and proline content. Microbe 2024, 4, 100124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, Y.R.; Cruz, S.P.; Chanway, C.; Kaschuk, G. Inoculation with Azospirillum brasilense or Bacillus spp. improves root growth and nutritional quality of araucaria (Araucaria angustifolia) seedlings. For. Ecol. Manag. 2024, 568, 122092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, S.; Srinivas, V.; Vidya, M.S.; Rathore, A. Plant growth-promoting activities of Streptomyces spp. in sorghum and rice. SpringerPlus 2013, 2, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Ahmad, S.; Yang, L.; Yan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, L.; Luo, Y. Preparation, biocontrol activity and growth promotion of biofertilizer containing Streptomyces aureoverticillatus HN6. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1090689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domínguez-González, K.G.; Robledo-Medrano, J.J.; Valdez-Alarcón, J.J.; Hernandez-Cristobal, O.; Martínez-Flores, H.E.; Cerna-Cortés, J.F.; Garnica-Romo, M.G.; Cortes-Martinez, R. Streptomyces spp. biofilmed solid inoculant improves microbial survival and plant-growth efficiency of Triticum aestivum. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Wang, Z.; Wang, C.; Yang, J.; Du, R.; Bing, H.; Xiang, W.; Wang, X.; Liu, C. Endophytic Streptomyces sp. NEAU-DD186 from moss with broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity: Biocontrol potential against Soilborne diseases and bioactive components. Phytopathology 2024, 114, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Htwe, A.Z.; Moh, S.M.; Soe, K.M.; Moe, K.; Yamakawa, T. Effects of biofertilizer produced from Bradyrhizobium and Streptomyces griseoflavus on plant growth, nodulation, nitrogen fixation, nutrient uptake, and seed yield of mung bean, cowpea, and soybean. Agronomy 2019, 9, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strain | Identification | Closest Species | Fragment Size (pb) | Similarity (%) | Siderophores (%) | Indolic Compounds (µg mL−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BEI-02A | Streptomyces sp. | S. thermocoprophilus NBRC 100771 | 785 | 98.85 | 38.5 | 15.9 |

| BEI-06A | Streptomyces sp. | S. poriferorum P01-B04 | 755 | 99.74 | 64.0 | 0 |

| BEI-07A | Streptomyces sp. | S. albus NRRL B-1811 | 765 | 100 | 26.5 | 4.2 |

| BEI-11A | Streptomyces sp. | S. speibonae PK-Blue | 790 | 98.99 | 0 | 0 |

| BEI-12A | Streptomyces sp. | S. spiralis NBRC 1421 | 728 | 99.86 | 20.6 | 1.5 |

| BEI-13A | Rhodococcus sp. | R. qingshengii JCM 15477 | 741 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| BEI-16A | Streptomyces sp. | S. poriferorum P01-B04 | 744 | 99.60 | 38.9 | 2.6 |

| BEI-17A | Streptomyces sp. | S. malaysiense MUSC 136 | 733 | 99.70 | 41.1 | 5.6 |

| BEI-18A | Streptomyces sp. | S. poriferorum P01-B04 | 641 | 99.06 | 63.6 | 5.0 |

| BEI-19A | Streptomyces sp. | Streptomyces sp. | 550 | 98.36 | 16.5 | 0 |

| BEI-22A | Streptomyces sp. | S. thermocoprophilus B19 | 778 | 99.49 | 11.8 | 10.4 |

| Experiment | SY (g/L) | AS (g/L) | SC (g/L) | SE (g/L) | C/N | Bacterial Concentration (Log CFU/mL) * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6.00 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 2.00 | 12.36 | 7.13 ± 0.25 |

| 2 | 4.00 | 2.00 | 4.00 | 2.00 | 4.66 | 6.57 ± 0.67 |

| 3 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 6.00 | 2.00 | 16.97 | 7.22 ± 0.06 |

| 4 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 10.08 | 7.40 ± 0.19 |

| 5 | 5.00 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 2.00 | 6.97 | 7.10 ± 0.43 |

| 6 | 5.00 | 0.00 | 5.00 | 2.00 | 14.44 | 6.99 ± 0.21 |

| 7 | 5.00 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 3.00 | 11.08 | 7.22 ± 0.27 |

| 8 | 4.00 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.00 | 7.86 | 6.33 ± 0.64 |

| 9 | 4.00 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 3.00 | 6.57 | 6.48 ± 0.67 |

| 10 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 5.00 | 3.00 | 12.77 | 7.09 ± 0.17 |

| 11 | 4.65 | 0.65 | 4.65 | 2.00 | 9.00 | 7.11 ± 0.01 |

| 12 | 4.65 | 0.65 | 4.00 | 2.65 | 7.90 | 6.39 ± 0.12 |

| 13 | 4.65 | 0.00 | 4.65 | 2.65 | 12.65 | 7.25 ± 0.42 |

| 14 | 4.00 | 0.65 | 4.65 | 2.65 | 8.56 | 6.72 ± 0.17 |

| 15 | 6.00 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 2.00 | 12.36 | 6.69 ± 0.12 |

| Treatment | TLR (cm) | RSA (cm2) | RV (cm3) | LVFR (cm) | LFR (cm) | LCR (cm) | SH (cm) | SD (mm) | SDM (g) | RDM (g) | DQI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soybean | T0 | 64.17 a | 23.33 a | 0.61 a | 15.36 a | 42.48 a | 6.33 a | 9.26 a | 1.93 a | 0.347 ab | 0.090 a | 0.051 ab |

| T10 | 99.34 b | 38.70 b | 1.22 c | 20.21 a | 66.14 b | 12.97 c | 11.08 a | 1.99 a | 0.353 ab | 0.148 b | 0.063 bc | |

| T50 | 86.75 ab | 34.40 ab | 1.09 bc | 20.81 a | 55.66 ab | 12.28 c | 12.04 a | 2.01 a | 0.372 b | 0.164 b | 0.065 c | |

| T100 | 70.45 ab | 27.27 ab | 0.86 abc | 15.55 a | 45.94 ab | 8.96 ab | 10.59 a | 2.09 a | 0.361 ab | 0.147 b | 0.068 c | |

| T500 | 62.80 a | 22.50 a | 0.66 a | 15.94 a | 39.02 a | 7.84 ab | 9.40 a | 2.09 a | 0.348 ab | 0.113 a | 0.062 bc | |

| T1000 | 64.79 a | 24.16 a | 0.72 ab | 14.63 a | 42.52 a | 7.63 a | 11.66 a | 1.92 a | 0.342 a | 0.102 a | 0.047 a | |

| Wheat | T0 | 22.17 ab | 5.36 ab | 0.107 a | 7.59 a | 11.25 a | 0.81 a | 15.99 a | 0.72 a | 0.035 a | 0.039 bc | 0.0030 a |

| T10 | 25.60 ab | 6.64 b | 0.137 a | 9.99 a | 11.89 a | 1.15 a | 19.32 a | 0.74 a | 0.085 b | 0.049 c | 0.0048 bc | |

| T50 | 19.90 ab | 4.91 ab | 0.103 a | 6.05 a | 10.69 a | 1.02 a | 15.59 a | 0.76 a | 0.057 ab | 0.033 abc | 0.0040 bc | |

| T100 | 25.10 ab | 6.18 ab | 0.130 a | 12.91 a | 12.62 a | 0.75 a | 15.72 a | 0.82 a | 0.085 b | 0.035 bc | 0.0056 c | |

| T500 | 27.95 b | 5.78 ab | 0.097 a | 15.90 a | 11.09 a | 0.93 a | 15.29 a | 0.81 a | 0.071 ab | 0.030 ab | 0.0047 bc | |

| T1000 | 14.26 a | 4.05 a | 0.103 a | 6.85 a | 8.26 a | 1.06 a | 16.05 a | 0.71 a | 0.049 ab | 0.017 a | 0.0032 ab |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nazari, M.T.; Rubert, A.; Schommer, V.A.; Machado, B.S.; Vancini, C.; Krein, D.D.C.; Ferrari, V.; Treichel, H.; Colla, L.M.; Piccin, J.S. From Isolation to Plant Growth Evaluation: Development of a Streptomyces-Based Bioinput Using Spent Yeast and Composting Leachate. Fermentation 2025, 11, 556. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11100556

Nazari MT, Rubert A, Schommer VA, Machado BS, Vancini C, Krein DDC, Ferrari V, Treichel H, Colla LM, Piccin JS. From Isolation to Plant Growth Evaluation: Development of a Streptomyces-Based Bioinput Using Spent Yeast and Composting Leachate. Fermentation. 2025; 11(10):556. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11100556

Chicago/Turabian StyleNazari, Mateus Torres, Aline Rubert, Vera Analise Schommer, Bruna Strieder Machado, Camila Vancini, Daniela Dal Castel Krein, Valdecir Ferrari, Helen Treichel, Luciane Maria Colla, and Jeferson Steffanello Piccin. 2025. "From Isolation to Plant Growth Evaluation: Development of a Streptomyces-Based Bioinput Using Spent Yeast and Composting Leachate" Fermentation 11, no. 10: 556. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11100556

APA StyleNazari, M. T., Rubert, A., Schommer, V. A., Machado, B. S., Vancini, C., Krein, D. D. C., Ferrari, V., Treichel, H., Colla, L. M., & Piccin, J. S. (2025). From Isolation to Plant Growth Evaluation: Development of a Streptomyces-Based Bioinput Using Spent Yeast and Composting Leachate. Fermentation, 11(10), 556. https://doi.org/10.3390/fermentation11100556