Assembly and Function of Gonad-Specific Non-Membranous Organelles in Drosophila piRNA Biogenesis

Abstract

1. Introduction

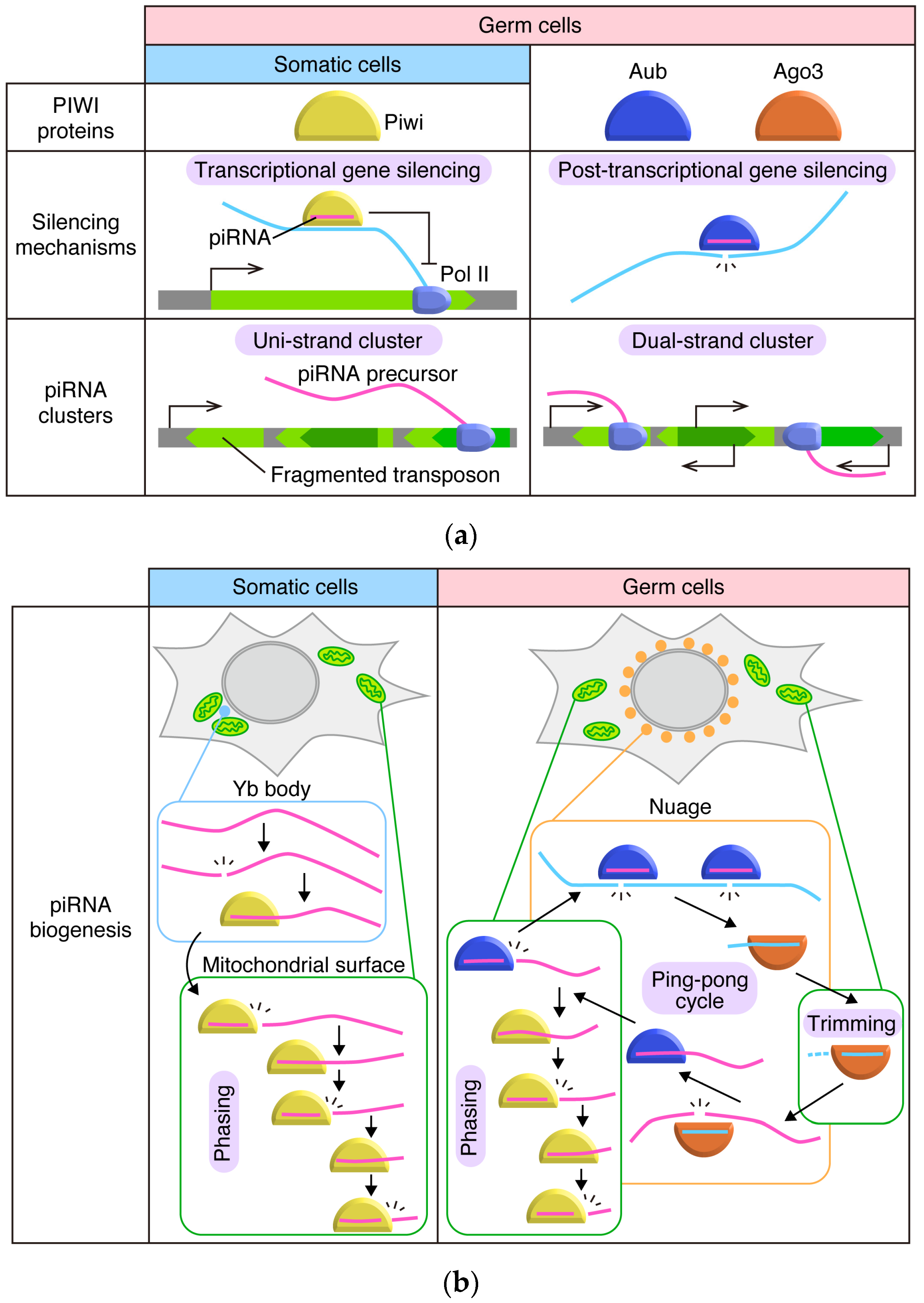

2. The piRNA Pathway in Drosophila Ovaries: The Outline

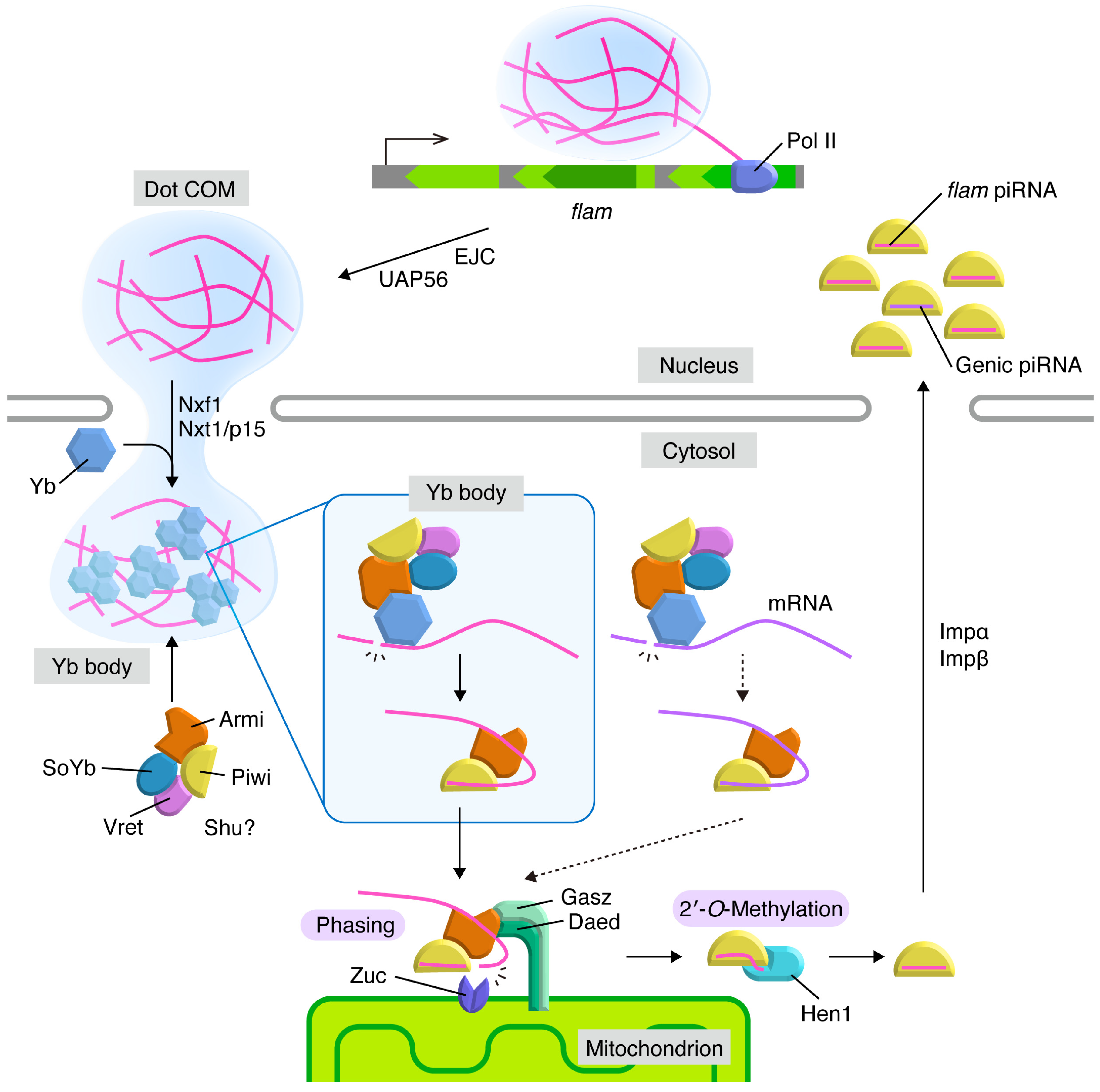

3. Flam Body/Dot COM: Dotty Structures Where piRNA Precursors Accumulate before Processing in Ovarian Somatic Cells

4. Yb Bodies: Cytoplasmic Non-Membranous Organelles Where Transposon-Targeting piRNA Precursors Undergo Primary Processing in Ovarian Somatic Cells

5. Mitochondria: Membranous Organelles that Serve as the Place for piRNA Maturation and Phased piRNA Biogenesis

6. Nuage: The Place for piRNA Amplification and Post-Transcriptional Repression through the Ping-Pong Cycle in Germ Cells

7. Perspective

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, X.; Fejes Tóth, K.; Aravin, A.A. piRNA biogenesis in Drosophila melanogaster. Trends Genet. 2017, 33, 882–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czech, B.; Munafò, M.; Ciabrelli, F.; Eastwood, E.L.; Fabry, M.H.; Kneuss, E.; Hannon, G.J. piRNA-guided genome defense: From biogenesis to silencing. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2018, 52, 131–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozata, D.M.; Gainetdinov, I.; Zoch, A.; O’Carroll, D.; Zamore, P.D. PIWI-interacting RNAs: Small RNAs with big functions. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019, 20, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parhad, S.S.; Theurkauf, W.E. Rapid evolution and conserved function of the piRNA pathway. Open. Biol. 2019, 9, 180181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ku, H.Y.; Lin, H. PIWI proteins and their interactors in piRNA biogenesis, germline development and gene expression. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2014, 1, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas-Ríos, P.; Simonelig, M. piRNAs and PIWI proteins: Regulators of gene expression in development and stem cells. Development 2018, 145, dev161786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashiro, H.; Siomi, M.C. PIWI-interacting RNA in Drosophila: Biogenesis, transposon regulation, and beyond. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 4404–4421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirakata, S.; Siomi, M.C. piRNA biogenesis in the germline: From transcription of piRNA genomic sources to piRNA maturation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1859, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimson, A.; Srivastava, M.; Fahey, B.; Woodcroft, B.J.; Chiang, H.R.; King, N.; Degnan, B.M.; Rokhsar, D.S.; Bartel, D.P. Early origins and evolution of microRNAs and Piwi-interacting RNAs in animals. Nature 2008, 455, 1193–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourque, G.; Burns, K.H.; Gehring, M.; Gorbunova, V.; Seluanov, A.; Hammell, M.; Imbeault, M.; Izsvák, Z.; Levin, H.L.; Macfarlan, T.S.; et al. Ten things you should know about transposable elements. Genome Biol. 2018, 19, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.P.; Barbash, D.A. Abundant and species-specific DINE-1 transposable elements in 12 Drosophila genomes. Genome Biol. 2008, 9, R39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennecke, J.; Aravin, A.A.; Stark, A.; Dus, M.; Kellis, M.; Sachidanandam, R.; Hannon, G.J. Discrete small RNA-generating loci as master regulators of transposon activity in Drosophila. Cell 2007, 128, 1089–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunawardane, L.S.; Saito, K.; Nishida, K.M.; Miyoshi, K.; Kawamura, Y.; Nagami, T.; Siomi, H.; Siomi, M.C. A Slicer-mediated mechanism for repeat-associated siRNA 5′ end formation in Drosophila. Science 2007, 315, 1587–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, D.N.; Chao, A.; Lin, H. piwi encodes a nucleoplasmic factor whose activity modulates the number and division rate of germline stem cells. Development 2000, 127, 503–514. [Google Scholar]

- Saito, K.; Nishida, K.M.; Mori, T.; Kawamura, Y.; Miyoshi, K.; Nagami, T.; Siomi, H.; Siomi, M.C. Specific association of Piwi with rasiRNAs derived from retrotransposon and heterochromatic regions in the Drosophila genome. Genes Dev. 2006, 20, 2214–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schüpbach, T.; Wieschaus, E. Female sterile mutations on the second chromosome of Drosophila melanogaster. II. Mutations blocking oogenesis or altering egg morphology. Genetics 1991, 129, 1119–1136. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, H.; Spradling, A.C. A novel group of pumilio mutations affects the asymmetric division of germline stem cells in the Drosophila ovary. Development 1997, 124, 2463–2476. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, D.N.; Chao, A.; Baker, J.; Chang, L.; Qiao, D.; Lin, H. A novel class of evolutionarily conserved genes defined by piwi are essential for stem cell self-renewal. Genes Dev. 1998, 12, 3715–3727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A.; Palumbo, G.; Bozzetti, M.P.; Tritto, P.; Pimpinelli, S.; Schäfer, U. Genetic and molecular characterization of sting, a gene involved in crystal formation and meiotic drive in the male germ line of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 1999, 151, 749–760. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Vagin, V.V.; Lee, S.; Xu, J.; Ma, S.; Xi, H.; Seitz, H.; Horwich, M.D.; Syrzycka, M.; Honda, B.M.; et al. Collapse of germline piRNAs in the absence of Argonaute3 reveals somatic piRNAs in flies. Cell 2009, 137, 509–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, K.M.; Iwasaki, Y.W.; Murota, Y.; Nagao, A.; Mannen, T.; Kato, Y.; Siomi, H.; Siomi, M.C. Respective functions of two distinct Siwi complexes assembled during PIWI-interacting RNA biogenesis in Bombyx germ cells. Cell Rep. 2015, 10, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmell, M.A.; Girard, A.; van de Kant, H.J.G.; Bourc’his, D.; Bestor, T.H.; de Rooij, D.G.; Hannon, G.J. MIWI2 is essential for spermatogenesis and repression of transposons in the mouse male germline. Dev. Cell 2007, 12, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, W.; Lin, H. miwi, a murine homolog of piwi, encodes a cytoplasmic protein essential for spermatogenesis. Dev. Cell 2002, 2, 819–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuramochi-Miyagawa, S.; Kimura, T.; Ijiri, T.W.; Isobe, T.; Asada, N.; Fujita, Y.; Ikawa, M.; Iwai, N.; Okabe, M.; Deng, W.; et al. Mili, a mammalian member of piwi family gene, is essential for spermatogenesis. Development 2004, 131, 839–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, K.; Inagaki, S.; Mituyama, T.; Kawamura, Y.; Ono, Y.; Sakota, E.; Kotani, H.; Asai, K.; Siomi, H.; Siomi, M.C. A regulatory circuit for piwi by the large Maf gene traffic jam in Drosophila. Nature 2009, 461, 1296–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niki, Y.; Yamaguchi, T.; Mahowald, A.P. Establishment of stable cell lines of Drosophila germ-line stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 16325–16330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, J.M.; Bratu, D.P. Drosophila melanogaster oogenesis: An overview. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015, 1328, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bastock, R.; St Johnston, D. Drosophila oogenesis. Curr. Biol. 2008, 18, R1082–R1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A.N.; Macdonald, P.M. aubergine encodes a Drosophila polar granule component required for pole cell formation and related to eIF2C. Development 2001, 128, 2823–2832. [Google Scholar]

- Rozhkov, N.V.; Hammell, M.; Hannon, G.J. Multiple roles for Piwi in silencing Drosophila transposons. Genes Dev. 2013, 27, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sienski, G.; Dönertas, D.; Brennecke, J. Transcriptional silencing of transposons by Piwi and Maelstrom and its impact on chromatin state and gene expression. Cell 2012, 151, 964–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Thomas, A.; Rogers, A.K.; Webster, A.; Marinov, G.K.; Liao, S.E.; Perkins, E.M.; Hur, J.K.; Aravin, A.A.; Fejes Tóth, K. Piwi induces piRNA-guided transcriptional silencing and establishment of a repressive chromatin state. Genes Dev. 2013, 27, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.H.; Elgin, S.C. Drosophila Piwi functions downstream of piRNA production mediating a chromatin-based transposon silencing mechanism in female germ line. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 21164–21169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klenov, M.S.; Sokolova, O.A.; Yakushev, E.Y.; Stolyarenko, A.D.; Mikhaleva, E.A.; Lavrov, S.A.; Gvozdev, V.A. Separation of stem cell maintenance and transposon silencing functions of Piwi protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 18760–18765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klenov, M.S.; Lavrov, S.A.; Korbut, A.P.; Stolyarenko, A.D.; Yakushev, E.Y.; Reuter, M.; Pillai, R.S.; Gvozdev, V.A. Impact of nuclear Piwi elimination on chromatin state in Drosophila melanogaster ovaries. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 6208–6218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.A.; Yin, H.; Sweeney, S.; Raha, D.; Snyder, M.; Lin, H. A major epigenetic programming mechanism guided by piRNAs. Dev. Cell 2013, 24, 502–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Siomi, M.C. Two distinct transcriptional controls triggered by nuclear Piwi-piRISCs in the Drosophila piRNA pathway. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2018, 53, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batki, J.; Schnabl, J.; Wang, J.; Handler, D.; Andreev, V.I.; Stieger, C.E.; Novatchkova, M.; Lampersberger, L.; Kauneckaite, K.; Xie, W.; et al. The nascent RNA binding complex SFiNX licenses piRNA-guided heterochromatin formation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2019, 26, 720–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Cheng, S.; Miao, N.; Xu, P.; Lu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, M.; Ouyang, X.; Yuan, X.; Liu, W.; et al. A Pandas complex adapted for piRNA-guided transcriptional silencing and heterochromatin formation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabry, M.H.; Ciabrelli, F.; Munafò, M.; Eastwood, E.L.; Kneuss, E.; Falciatori, I.; Falconio, F.A.; Hannon, G.J.; Czech, B. piRNA-guided co-transcriptional silencing coopts nuclear export factors. Elife 2019, 8, e47999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murano, K.; Iwasaki, Y.W.; Ishizu, H.; Mashiko, A.; Shibuya, A.; Kondo, S.; Adachi, S.; Suzuki, S.; Saito, K.; Natsume, T.; et al. Nuclear RNA export factor variant initiates piRNA-guided co-transcriptional silencing. EMBO J. 2019, 38, e102870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwasaki, Y.W.; Murano, K.; Ishizu, H.; Shibuya, A.; Iyoda, Y.; Siomi, M.C.; Siomi, H.; Saito, K. Piwi modulates chromatin accessibility by regulating multiple factors including histone H1 to repress transposons. Mol. Cell 2016, 63, 408–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sienski, G.; Batki, J.; Senti, K.A.; Dönertas, D.; Tirian, L.; Meixner, K.; Brennecke, J. Silencio/CG9754 connects the Piwi-piRNA complex to the cellular heterochromatin machinery. Genes Dev. 2015, 29, 2258–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Gu, J.; Jin, Y.; Luo, Y.; Preall, J.B.; Ma, J.; Czech, B.; Hannon, G.J. Panoramix enforces piRNA-dependent cotranscriptional silencing. Science 2015, 350, 339–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dönertas, D.; Sienski, G.; Brennecke, J. Drosophila Gtsf1 is an essential component of the Piwi-mediated transcriptional silencing complex. Genes Dev. 2013, 27, 1693–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtani, H.; Iwasaki, Y.W.; Shibuya, A.; Siomi, H.; Siomi, M.C.; Saito, K. DmGTSF1 is necessary for Piwi-piRISC-mediated transcriptional transposon silencing in the Drosophila ovary. Genes Dev. 2013, 27, 1656–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muerdter, F.; Guzzardo, P.M.; Gillis, J.; Luo, Y.; Yu, Y.; Chen, C.; Fekete, R.; Hannon, G.J. A genome-wide RNAi screen draws a genetic framework for transposon control and primary piRNA biogenesis in Drosophila. Mol. Cell 2013, 50, 736–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, C.D.; Brennecke, J.; Dus, M.; Stark, A.; McCombie, W.R.; Sachidanandam, R.; Hannon, G.J. Specialized piRNA pathways act in germline and somatic tissues of the Drosophila ovary. Cell 2009, 137, 522–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamanaka, S.; Siomi, M.C.; Siomi, H. piRNA clusters and open chromatin structure. Mob. DNA 2014, 5, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, P.R.; Tirian, L.; Vunjak, M.; Brennecke, J. A heterochromatin-dependent transcription machinery drives piRNA expression. Nature 2017, 549, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klattenhoff, C.; Xi, H.; Li, C.; Lee, S.; Xu, J.; Khurana, J.S.; Zhang, F.; Schultz, N.; Koppetsch, B.S.; Nowosielska, A.; et al. The Drosophila HP1 homolog Rhino is required for transposon silencing and piRNA production by dual-strand clusters. Cell 2009, 138, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohn, F.; Sienski, G.; Handler, D.; Brennecke, J. The Rhino-Deadlock-Cutoff complex licenses noncanonical transcription of dual-Strand piRNA clusters in Drosophila. Cell 2014, 157, 1364–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Schultz, N.; Zhang, F.; Parhad, S.S.; Tu, S.; Vreven, T.; Zamore, P.D.; Weng, Z.; Theurkauf, W.E. The HP1 homolog Rhino anchors a nuclear complex that suppresses piRNA precursor splicing. Cell 2014, 157, 1353–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Thomas, A.; Stuwe, E.; Li, S.; Du, J.; Marinov, G.; Rozhkov, N.; Chen, Y.C.; Luo, Y.; Sachidanandam, R.; Fejes Tóth, K.; et al. Transgenerationally inherited piRNAs trigger piRNA biogenesis by changing the chromatin of piRNA clusters and inducing precursor processing. Genes Dev. 2014, 28, 1667–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pane, A.; Jiang, P.; Zhao, D.Y.; Singh, M.; Schüpbach, T. The Cutoff protein regulates piRNA cluster expression and piRNA production in the Drosophila germline. EMBO J. 2011, 30, 4601–4615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElMaghraby, M.F.; Andersen, P.R.; Pühringer, F.; Hohmann, U.; Meixner, K.; Lendl, T.; Tirian, L.; Brennecke, J. A heterochromatin-specific RNA export pathway facilitates piRNA production. Cell 2019, 178, 964–979.e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneuss, E.; Munafò, M.; Eastwood, E.L.; Deumer, U.S.; Preall, J.B.; Hannon, G.J.; Czech, B. Specialization of the Drosophila nuclear export family protein Nxf3 for piRNA precursor export. Genes Dev. 2019, 33, 1208–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robine, N.; Lau, N.C.; Balla, S.; Jin, Z.; Okamura, K.; Kuramochi-Miyagawa, S.; Blower, M.D.; Lai, E.C. A broadly conserved pathway generates 3′UTR-directed primary piRNAs. Curr. Biol. 2009, 19, 2066–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, Y.W.; Siomi, M.C.; Siomi, H. PIWI-interacting RNA: Its biogenesis and functions. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2015, 84, 405–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szakmary, A.; Reedy, M.; Qi, H.; Lin, H. The Yb protein defines a novel organelle and regulates male germline stem cell self-renewal in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Cell Biol. 2009, 185, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, K.; Ishizu, H.; Komai, M.; Kotani, H.; Kawamura, Y.; Nishida, K.M.; Siomi, H.; Siomi, M.C. Roles for the Yb body components Armitage and Yb in primary piRNA biogenesis in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 2010, 24, 2493–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, H.; Watanabe, T.; Ku, H.Y.; Liu, N.; Zhong, M.; Lin, H. The Yb body, a major site for Piwi-associated RNA biogenesis and a gateway for Piwi expression and transport to the nucleus in somatic cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 3789–3797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivieri, D.; Sykora, M.M.; Sachidanandam, R.; Mechtler, K.; Brennecke, J. An in vivo RNAi assay identifies major genetic and cellular requirements for primary piRNA biogenesis in Drosophila. EMBO J. 2010, 29, 3301–3317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handler, D.; Olivieri, D.; Novatchkova, M.; Gruber, F.S.; Meixner, K.; Mechtler, K.; Stark, A.; Sachidanandam, R.; Brennecke, J. A systematic analysis of Drosophila TUDOR domain-containing proteins identifies Vreteno and the Tdrd12 family as essential primary piRNA pathway factors. EMBO J. 2011, 30, 3977–3993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivieri, D.; Senti, K.A.; Subramanian, S.; Sachidanandam, R.; Brennecke, J. The cochaperone Shutdown defines a group of biogenesis factors essential for all piRNA populations in Drosophila. Mol. Cell 2012, 47, 954–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagin, V.V.; Yu, Y.; Jankowska, A.; Luo, Y.; Wasik, K.A.; Malone, C.D.; Harrison, E.; Rosebrock, A.; Wakimoto, B.T.; Fagegaltier, D.; et al. Minotaur is critical for primary piRNA biogenesis. RNA 2013, 19, 1064–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munafò, M.; Manelli, V.; Falconio, F.A.; Sawle, A.; Kneuss, E.; Eastwood, E.L.; Seah, J.W.E.; Czech, B.; Hannon, G.J. Daedalus and Gasz recruit Armitage to mitochondria, bringing piRNA precursors to the biogenesis machinery. Genes Dev. 2019, 33, 844–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handler, D.; Meixner, K.; Pizka, M.; Lauss, K.; Schmied, C.; Gruber, F.S.; Brennecke, J. The genetic makeup of the Drosophila piRNA pathway. Mol. Cell 2013, 50, 762–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, R.R.; Homolka, D.; Chen, K.M.; Sachidanandam, R.; Fauvarque, M.O.; Pillai, R.S. Recruitment of Armitage and Yb to a transcript triggers its phased processing into primary piRNAs in Drosophila ovaries. PLoS Genet. 2017, 13, e1006956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Li, Y.; Szulwach, K.E.; Zhang, G.; Jin, P.; Chen, D. AGO3 Slicer activity regulates mitochondria-nuage localization of Armitage and piRNA amplification. J. Cell Biol. 2014, 206, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, H.A.; Koppetsch, B.S.; Wu, J.; Theurkauf, W.E. The Drosophila SDE3 homolog armitage is required for oskar mRNA silencing and embryonic axis specification. Cell 2004, 116, 817–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, D.T.; Wang, W.; Tipping, C.; Gainetdinov, I.; Weng, Z.; Zamore, P.D. The RNA-binding ATPase, Armitage, couples piRNA amplification in nuage to phased piRNA production on mitochondria. Mol. Cell 2019, 74, 982–995.e986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamparini, A.L.; Davis, M.Y.; Malone, C.D.; Vieira, E.; Zavadil, J.; Sachidanandam, R.; Hannon, G.J.; Lehmann, R. Vreteno, a gonad-specific protein, is essential for germline development and primary piRNA biogenesis in Drosophila. Development 2011, 138, 4039–4050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohn, F.; Handler, D.; Brennecke, J. piRNA-guided slicing specifies transcripts for Zucchini-dependent, phased piRNA biogenesis. Science 2015, 348, 812–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.W.; Wang, W.; Li, C.; Weng, Z.; Zamore, P.D. piRNA-guided transposon cleavage initiates Zucchini-dependent, phased piRNA production. Science 2015, 348, 817–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pane, A.; Wehr, K.; Schüpbach, T. zucchini and squash encode two putative nucleases required for rasiRNA production in the Drosophila germline. Dev. Cell 2007, 12, 851–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Xu, J.; Koppetsch, B.S.; Wang, J.; Tipping, C.; Ma, S.; Weng, Z.; Theurkauf, W.E.; Zamore, P.D. Heterotypic piRNA Ping-Pong requires Qin, a protein with both E3 ligase and Tudor domains. Mol. Cell 2011, 44, 572–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, A.; Kai, T. The tudor domain protein Kumo is required to assemble the nuage and to generate germline piRNAs in Drosophila. EMBO J. 2012, 31, 870–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, A.K.; Kai, T. Unique germ-line organelle, nuage, functions to repress selfish genetic elements in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 6714–6719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahowald, A.P. Polar granules of Drosophila. 3. The continuity of polar granules during the life cycle of Drosophila. J. Exp. Zool. 1971, 176, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahowald, A.P. Assembly of the Drosophila germ plasm. Int. Rev. Cytol. 2001, 203, 187–213. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, C.; Zanni, V.; Brasset, E.; Eymery, A.; Zhang, L.; Mteirek, R.; Jensen, S.; Rong, Y.S.; Vaury, C. “Dot COM”, a nuclear transit center for the primary piRNA pathway in Drosophila. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e72752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, C.; Brasset, E.; Sarkar, A.; Vaury, C. Export of piRNA precursors by EJC triggers assembly of cytoplasmic Yb-body in Drosophila. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, O.A.; Ilyin, A.A.; Poltavets, A.S.; Nenasheva, V.V.; Mikhaleva, E.A.; Shevelyov, Y.Y.; Klenov, M.S. Yb body assembly on the flamenco piRNA precursor transcripts reduces genic piRNA production. Mol. Biol. Cell 2019, 30, 1544–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, C.; Brasset, E.; Vaury, C. flam piRNA precursors channel from the nucleus to the cytoplasm in a temporally regulated manner along Drosophila oogenesis. Mob. DNA 2019, 10, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murota, Y.; Ishizu, H.; Nakagawa, S.; Iwasaki, Y.W.; Shibata, S.; Kamatani, M.K.; Saito, K.; Okano, H.; Siomi, H.; Siomi, M.C. Yb integrates piRNA intermediates and processing factors into perinuclear bodies to enhance piRISC assembly. Cell Rep. 2014, 8, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, N.C.; Robine, N.; Martin, R.; Chung, W.J.; Niki, Y.; Berezikov, E.; Lai, E.C. Abundant primary piRNAs, endo-siRNAs, and microRNAs in a Drosophila ovary cell line. Genome Res. 2009, 19, 1776–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desset, S.; Meignin, C.; Dastugue, B.; Vaury, C. COM, a heterochromatic locus governing the control of independent endogenous retroviruses from Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 2003, 164, 501–509. [Google Scholar]

- Pélisson, A.; Song, S.U.; Prud’homme, N.; Smith, P.A.; Bucheton, A.; Corces, V.G. Gypsy transposition correlates with the production of a retroviral envelope-like protein under the tissue-specific control of the Drosophila flamenco gene. EMBO J. 1994, 13, 4401–4411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prud’homme, N.; Gans, M.; Masson, M.; Terzian, C.; Bucheton, A. Flamenco, a gene controlling the gypsy retrovirus of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 1995, 139, 697–711. [Google Scholar]

- Goriaux, C.; Desset, S.; Renaud, Y.; Vaury, C.; Brasset, E. Transcriptional properties and splicing of the flamenco piRNA cluster. EMBO Rep. 2014, 15, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirakata, S.; Ishizu, H.; Fujita, A.; Tomoe, Y.; Siomi, M.C. Requirements for multivalent Yb body assembly in transposon silencing in Drosophila. EMBO Rep. 2019, 20, e47708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishizu, H.; Iwasaki, Y.W.; Hirakata, S.; Ozaki, H.; Iwasaki, W.; Siomi, H.; Siomi, M.C. Somatic primary piRNA biogenesis driven by cis-acting RNA elements and trans-acting Yb. Cell Rep. 2015, 12, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishizu, H.; Kinoshita, T.; Hirakata, S.; Komatsuzaki, C.; Siomi, M.C. Distinct and collaborative functions of Yb and Armitage in transposon-targeting piRNA biogenesis. Cell Rep. 2019, 27, 1822–1835.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, A.K.; Situ, K.; Perkins, E.M.; Fejes Tóth, K. Zucchini-dependent piRNA processing is triggered by recruitment to the cytoplasmic processing machinery. Genes Dev. 2017, 31, 1858–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashiro, H.; Negishi, M.; Kinoshita, T.; Ishizu, H.; Ohtani, H.; Siomi, M.C. Armitage determines Piwi-piRISC processing from precursor formation and quality control to inter-organelle translocation. EMBO Rep. 2019. under review. [Google Scholar]

- Nishimasu, H.; Ishizu, H.; Saito, K.; Fukuhara, S.; Kamatani, M.K.; Bonnefond, L.; Matsumoto, N.; Nishizawa, T.; Nakanaga, K.; Aoki, J.; et al. Structure and function of Zucchini endoribonuclease in piRNA biogenesis. Nature 2012, 491, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, F.; Reuter, M.; Kasaruho, A.; Schulz, E.C.; Pillai, R.S.; Barabas, O. Crystal structure of the primary piRNA biogenesis factor Zucchini reveals similarity to the bacterial PLD endonuclease Nuc. RNA 2012, 18, 2128–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feltzin, V.L.; Khaladkar, M.; Abe, M.; Parisi, M.; Hendriks, G.J.; Kim, J.; Bonini, N.M. The exonuclease Nibbler regulates age-associated traits and modulates piRNA length in Drosophila. Aging Cell 2015, 14, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ma, Z.; Niu, K.; Xiao, Y.; Wu, X.; Pan, C.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, N. Antagonistic roles of Nibbler and Hen1 in modulating piRNA 3′ ends in Drosophila. Development 2016, 143, 530–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, R.; Schnabl, J.; Handler, D.; Mohn, F.; Ameres, S.L.; Brennecke, J. Genetic and mechanistic diversity of piRNA 3′-end formation. Nature 2016, 539, 588–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horwich, M.D.; Li, C.; Matranga, C.; Vagin, V.; Farley, G.; Wang, P.; Zamore, P.D. The Drosophila RNA methyltransferase, DmHen1, modifies germline piRNAs and single-stranded siRNAs in RISC. Curr. Biol. 2007, 17, 1265–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, K.; Sakaguchi, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Siomi, H.; Siomi, M.C. Pimet, the Drosophila homolog of HEN1, mediates 2’-O-methylation of Piwi-interacting RNAs at their 3′ ends. Genes Dev. 2007, 21, 1603–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homolka, D.; Pandey, R.R.; Goriaux, C.; Brasset, E.; Vaury, C.; Sachidanandam, R.; Fauvarque, M.O.; Pillai, R.S. PIWI slicing and RNA elements in precursors instruct directional primary piRNA biogenesis. Cell Rep. 2015, 12, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Han, B.W.; Tipping, C.; Ge, D.T.; Zhang, Z.; Weng, Z.; Zamore, P.D. Slicing and binding by Ago3 or Aub trigger Piwi-bound piRNA production by distinct mechanisms. Mol. Cell 2015, 59, 819–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yashiro, R.; Murota, Y.; Nishida, K.M.; Yamashiro, H.; Fujii, K.; Ogai, A.; Yamanaka, S.; Negishi, L.; Siomi, H.; Siomi, M.C. Piwi nuclear localization and its regulatory mechanism in Drosophila ovarian somatic cells. Cell Rep. 2018, 23, 3647–3657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preall, J.B.; Czech, B.; Guzzardo, P.M.; Muerdter, F.; Hannon, G.J. shutdown is a component of the Drosophila piRNA biogenesis machinery. RNA 2012, 18, 1446–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, A.; Li, S.; Hur, J.K.; Wachsmuth, M.; Bois, J.S.; Perkins, E.M.; Patel, D.J.; Aravin, A.A. Aub and Ago3 are recruited to nuage through two mechanisms to form a ping-pong complex assembled by Krimper. Mol. Cell 2015, 59, 564–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibanov, M.V.; Egorova, K.S.; Ryazansky, S.S.; Sokolova, O.A.; Kotov, A.A.; Olenkina, O.M.; Stolyarenko, A.D.; Gvozdev, V.A.; Olenina, L.V. A novel organelle, the piNG-body, in the nuage of Drosophila male germ cells is associated with piRNA-mediated gene silencing. Mol. Biol. Cell 2011, 22, 3410–3419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravin, A.A.; van der Heijden, G.W.; Castañeda, J.; Vagin, V.V.; Hannon, G.J.; Bortvin, A. Cytoplasmic compartmentalization of the fetal piRNA pathway in mice. PLoS Genet. 2009, 5, e1000764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Diehl-Jones, W.; Lasko, P. Localization of vasa protein to the Drosophila pole plasm is independent of its RNA-binding and helicase activities. Development 1994, 120, 1201–1211. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xiol, J.; Spinelli, P.; Laussmann, M.A.; Homolka, D.; Yang, Z.; Cora, E.; Couté, Y.; Conn, S.; Kadlec, J.; Sachidanandam, R.; et al. RNA clamping by Vasa assembles a piRNA amplifier complex on transposon transcripts. Cell 2014, 157, 1698–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nott, T.J.; Petsalaki, E.; Farber, P.; Jervis, D.; Fussner, E.; Plochowietz, A.; Craggs, T.D.; Bazett-Jones, D.P.; Pawson, T.; Forman-Kay, J.D.; et al. Phase transition of a disordered nuage protein generates environmentally responsive membraneless organelles. Mol. Cell 2015, 57, 936–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, V.S.; Kai, T. Repression of retroelements in Drosophila germline via piRNA pathway by the tudor domain protein Tejas. Curr. Biol. 2010, 20, 724–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findley, S.D.; Tamanaha, M.; Clegg, N.J.; Ruohola-Baker, H. Maelstrom, a Drosophila spindle-class gene, encodes a protein that colocalizes with Vasa and RDE1/AGO1 homolog, Aubergine, in nuage. Development 2003, 130, 859–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Wang, J.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Koppetsch, B.S.; Schultz, N.; Vreven, T.; Meignin, C.; Davis, I.; Zamore, P.D.; et al. UAP56 couples piRNA clusters to the perinuclear transposon silencing machinery. Cell 2012, 151, 871–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, V.; Kimm, N.; Lehmann, R. A maternal screen for genes regulating Drosophila oocyte polarity uncovers new steps in meiotic progression. Genetics 2007, 176, 1967–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Iwasaki, Y.W.; Shibuya, A.; Carninci, P.; Tsuchizawa, Y.; Ishizu, H.; Siomi, M.C.; Siomi, H. Krimper enforces an antisense bias on piRNA pools by binding AGO3 in the Drosophila germline. Mol. Cell 2015, 59, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagao, A.; Sato, K.; Nishida, K.M.; Siomi, H.; Siomi, M.C. Gender-specific hierarchy in nuage localization of PIWI-interacting RNA factors in Drosophila. Front. Genet. 2011, 2, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Koppetsch, B.S.; Wang, J.; Tipping, C.; Weng, Z.; Theurkauf, W.E.; Zamore, P.D. Antisense piRNA amplification, but not piRNA production or nuage assembly, requires the Tudor-domain protein Qin. EMBO J. 2014, 33, 536–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumiyoshi, T.; Sato, K.; Yamamoto, H.; Iwasaki, Y.W.; Siomi, H.; Siomi, M.C. Loss of l(3)mbt leads to acquisition of the ping-pong cycle in Drosophila ovarian somatic cells. Genes Dev. 2016, 30, 1617–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hirakata, S.; Siomi, M.C. Assembly and Function of Gonad-Specific Non-Membranous Organelles in Drosophila piRNA Biogenesis. Non-Coding RNA 2019, 5, 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/ncrna5040052

Hirakata S, Siomi MC. Assembly and Function of Gonad-Specific Non-Membranous Organelles in Drosophila piRNA Biogenesis. Non-Coding RNA. 2019; 5(4):52. https://doi.org/10.3390/ncrna5040052

Chicago/Turabian StyleHirakata, Shigeki, and Mikiko C. Siomi. 2019. "Assembly and Function of Gonad-Specific Non-Membranous Organelles in Drosophila piRNA Biogenesis" Non-Coding RNA 5, no. 4: 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/ncrna5040052

APA StyleHirakata, S., & Siomi, M. C. (2019). Assembly and Function of Gonad-Specific Non-Membranous Organelles in Drosophila piRNA Biogenesis. Non-Coding RNA, 5(4), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/ncrna5040052