Bioprinted Recombinant Human-Collagen-Based In Vitro Skin Models for Assessing Effects of Nano-ZnO on Dermis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

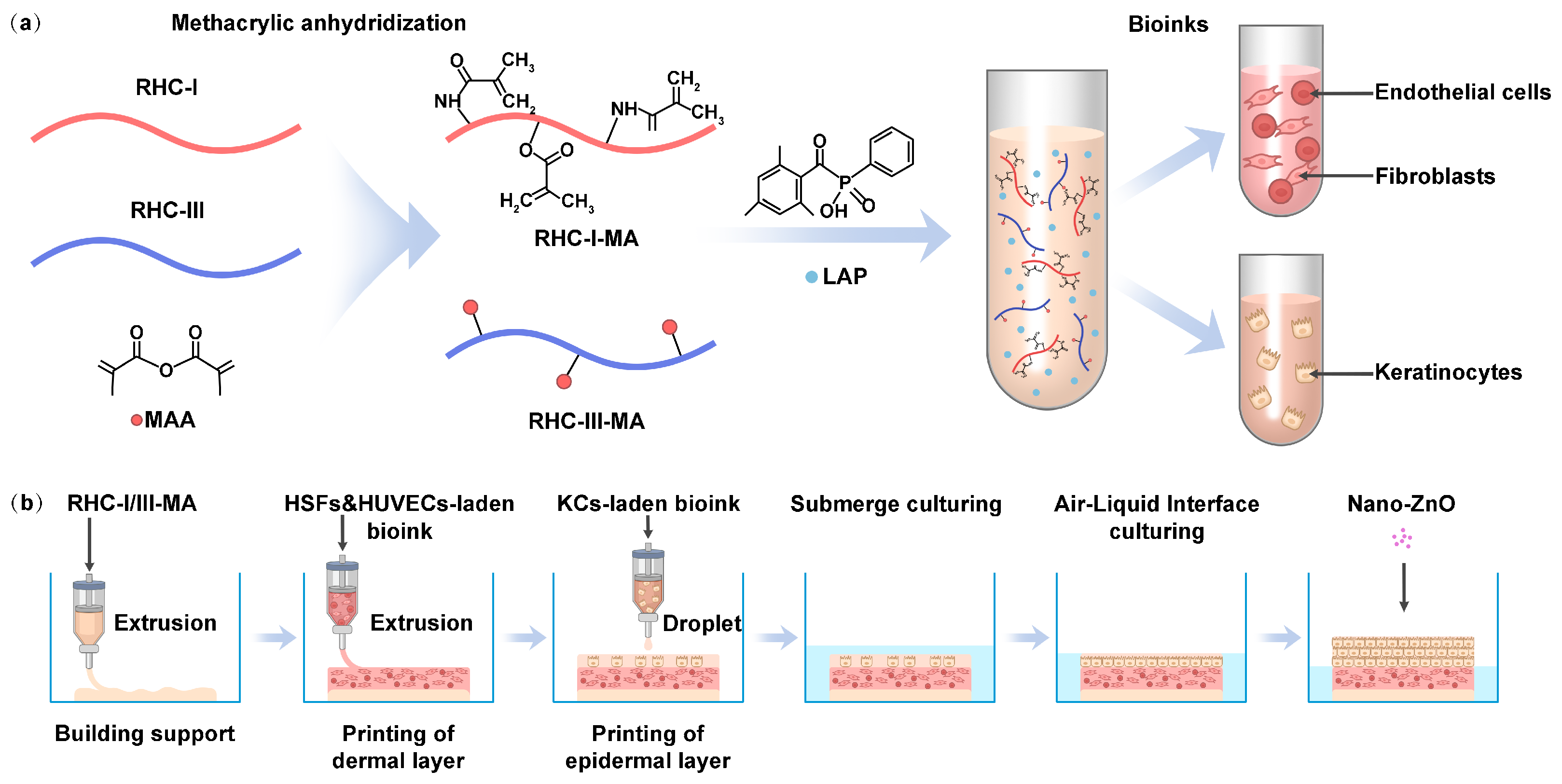

2.1. Methacrylation of Recombinant Human Collagen

2.1.1. FTIR

2.1.2. 1H-NMR

2.1.3. Substitution Degree

2.2. Internal Morphological Structure

2.3. Photorheological Characterization

2.4. Mechanical Property Analysis

2.5. Printability and Cell Survivability

2.6. Histological Examination of In Vitro 3D Skin Models

2.7. Gene Expression Analysis

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials and Reagents

4.2. Preparation of the Bioink Materials and Reagents

4.3. Determination of MAA Grafting Ratio in RHC-MA Solutions

4.3.1. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

4.3.2. Proton Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (1H-NMR)

4.3.3. TNBS Assay

4.4. Morphological Characterization

4.5. Physicochemical Properties of the Hydrogels

4.5.1. Characterization of Photorheological Properties

4.5.2. Mechanical Properties

4.5.3. Investigation of Printability and Cell Survivability

4.6. Cell-Laden Bioprinted 3D Skin Products

4.7. Characterization of 3D Skin Model

4.8. qRT-PCR

4.9. Statistical Analyses

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amirrah, I.N.; Lokanathan, Y.; Zulkiflee, I.; Wee, M.; Motta, A.; Fauzi, M.B. A Comprehensive Review on Collagen Type I Development of Biomaterials for Tissue Engineering: From Biosynthesis to Bioscaffold. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirois, J.P.; Heinz, A. Matrikines in the skin: Origin, effects, and therapeutic potential. Pharmacol. Ther. 2024, 260, 108682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, M.R.; Jennifer, L. Skin collagen through the lifestages: Importance for skin health and beauty. Plast. Aesthetic Res. 2021, 8, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xing, F.; Wang, J.; Luo, X.; Kong, Y.; Zhang, G. Age-related changes in the ratio of Type I/III collagen and fibril diameter in mouse skin. Regen. Biomater. 2023, 10, rbac110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Q.; Jiao, T.; Zhao Wang, H.; Yang, S.; Li, D. 3D Bioprinted Skin Substitutes for Accelerated Wound Healing and Reduced Scar. J. Bionic Eng. 2021, 18, 900–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thy, L.T.M.; Thanh, L.N.P.; Dat, N.T.; Dat, N.M. Review on the application of inorganic UV filters in sunscreens: Mechanisms, evaluation methods, toxicity, and safety enhancements. Results Surf. Interfaces 2025, 20, 100580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D.; Huang, Y.; Fang, Z.; Liu, D.; Wang, Q.; Xu, Y.; Li, P.; Li, J. Zinc oxide nanoparticles for skin wound healing: A systematic review from the perspective of disease types. Mater. Today Bio 2025, 34, 102221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Cui, C.; Sun, S.; Wu, S.; Chen, S.; Ma, J.; Li, C.M. Electrospun ZnO-loaded chitosan/PCL bilayer membranes with spatially designed structure for accelerated wound healing. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 282, 119131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Ilves, M.; Mäenpää, K.; Zhao, L.; El-Nezami, H.; Karisola, P.; Alenius, H. ZnO Nanoparticles as Potent Inducers of Dermal Immunosuppression in Contact Hypersensitivity in Mice. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 29479–29491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Wen, T.; Ma, Y.; Zeng, Q.; Li, P.; Zhou, W. Biomimetic hyaluronic acid-stabilized zinc oxide nanoparticles in acne treatment: A preclinical and clinical approach. J. Control. Release 2025, 382, 113754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Feng, X.; Wei, L.; Chen, L.; Song, B.; Shao, L. The toxicology of ion-shedding zinc oxide nanoparticles. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2016, 46, 348–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, L.; Song, E.; Song, Y. “Iron free” zinc oxide nanoparticles with ion-leaking properties disrupt intracellular ROS and iron homeostasis to induce ferroptosis. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Peng, H.; Shao, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Pi, J.; Guo, J. NRF2 deficiency sensitizes human keratinocytes to zinc oxide nanoparticles-induced autophagy and cytotoxicity. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2021, 87, 103721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Anderson, D.; Dhawan, A. Zinc oxide nanoparticles induce oxidative DNA damage and ROS-triggered mitochondria mediated apoptosis in human liver cells (HepG2). Apoptosis 2012, 17, 852–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balavigneswaran, C.K.; Selvaraj, S.; Vasudha, T.K.; Iniyan, S.; Muthuvijayan, V. Tissue engineered skin substitutes: A comprehensive review of basic design, fabrication using 3D printing, recent advances and challenges. Biomater. Adv. 2023, 153, 213570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggiotto, F.; Valle, E.D.; Fietta, A.; Visentin, L.M.; Giomo, M.; Cimetta, E. 3D bioprinting of a perfusable skin-on-chip model suitable for drug testing and wound healing studies. Mater. Today Bio 2025, 33, 101974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauwereyns, J.; Bajramovic, J.; Bert, B.; Camenzind, S.; De Kock, J.; Elezović, A.; Erden, S.; Gonzalez-Uarquin, F.; Ulman, Y.I.; Hoffmann, O.I.; et al. Toward a common interpretation of the 3Rs principles in animal research. Lab Anim. 2024, 53, 347–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallo, A.; Al Kayal, T.; Mero, A.; Mezzetta, A.; Pisani, A.; Foffa, I.; Vecoli, C.; Buscemi, M.; Guazzelli, L.; Soldani, G.; et al. Marine Collagen-Based Bioink for 3D Bioprinting of a Bilayered Skin Model. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Zhu, X.; Lv, S.; Yang, C.; Wang, Z.; Liao, M.; Zhou, B.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, S.; Chen, P.; et al. 3D bioprinting of prefabricated artificial skin with multicomponent hydrogel for skin and hair follicle regeneration. Theranostics 2025, 15, 2933–2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauzi, M.B.; Rashidbenam, Z.; Saim, A.B.; Idrus, R.B.H. Preliminary Study of In Vitro Three-Dimensional Skin Model Using an Ovine Collagen Type I Sponge Seeded with Co-Culture Skin Cells: Submerged versus Air-Liquid Interface Conditions. Polymers 2020, 12, 2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, F.; Hong, Y.; Liang, R.; Zhang, X.; Liao, Y.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, J.; Sheng, Z.; Xie, C.; Peng, Z.; et al. Rapid printing of bio-inspired 3D tissue constructs for skin regeneration. Biomaterials 2020, 258, 120287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Liu, W.; Xie, X.; Lei, H. Development and application of recombinant collagen in dermatology. React. Funct. Polym. 2025, 217, 106495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, A.L.; Costa-Gouveia, J.; de Castro, J.V.; Sotelo, C.G.; Vázquez, J.A.; Pérez-Martín, R.I.; Torrado, E.; Neves, N.; Reis, R.L.; Castro, A.G.; et al. Study of the immunologic response of marine-derived collagen and gelatin extracts for tissue engineering applications. Acta Biomater. 2022, 141, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Hu, H.; Wang, J.; Qiu, H.; Gao, Y.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Tang, Y.; Song, L.; Ramshaw, J.; et al. Characterization of recombinant humanized collagen type III and its influence on cell behavior and phenotype. J. Leather Sci. Eng. 2022, 4, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Hao, J.; Lei, H.; Chen, Y.; Liu, L.; Jia, L.; Gu, J.; Kang, H.; Shi, J.; He, J.; et al. Recombinant collagen for the repair of skin wounds and photo-aging damage. Regen. Biomater. 2024, 11, rbae108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stefano, A.B.; Urrata, V.; Schilders, K.; Franza, M.; Di Leo, S.; Moschella, F.; Cordova, A.; Toia, F. Three-Dimensional Bioprinting Techniques in Skin Regeneration: Current Insights and Future Perspectives. Life 2025, 15, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, K.; Li, X.; Schrobback, K.; Sheikhi, A.; Annabi, N.; Leijten, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.S.; Hutmacher, D.W.; Klein, T.J.; et al. Structural analysis of photocrosslinkable methacryloyl-modified protein derivatives. Biomaterials 2017, 139, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasany, M.; Talebian, S.; Sadat, S.; Ranjbar, N.; Mehrali, M.; Wallace, G.G.; Mehrali, M. Synthesis, properties, and biomedical applications of alginate methacrylate (ALMA)-based hydrogels: Current advances and challenges. Appl. Mater. Today 2021, 24, 101150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadian, Z.; Correia, A.; Hasany, M.; Figueiredo, P.; Dobakhti, F.; Eskandari, M.R.; Hosseini, S.H.; Abiri, R.; Khorshid, S.; Hirvonen, J.; et al. A Hydrogen-Bonded Extracellular Matrix-Mimicking Bactericidal Hydrogel with Radical Scavenging and Hemostatic Function for pH-Responsive Wound Healing Acceleration. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2021, 10, 2001122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterley, A.S.; Laity, P.; Holland, C.; Weidner, T.; Woutersen, S.; Giubertoni, G. Broadband Multidimensional Spectroscopy Identifies the Amide II Vibrations in Silkworm Films. Molecules 2022, 27, 6275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertlein, S.; Brown, G.; Lim, K.S.; Jungst, T.; Boeck, T.; Blunk, T.; Tessmar, J.; Hooper, G.J.; Woodfield, T.B.F.; Groll, J. Thiol–Ene Clickable Gelatin: A Platform Bioink for Multiple 3D Biofabrication Technologies. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1703404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.H.; Lum, N.; Seow, L.Y.; Lim, P.Q.; Tan, L.P. Synthesis and Characterization of Types A and B Gelatin Methacryloyl for Bioink Applications. Materials 2016, 9, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Datta, P. Characterization of Bioinks for 3D Bioprinting, in 3D Printable Gel-Inks for Tissue Engineering: Chemistry, Processing, and Applications; Kumar, A., Voicu, S.I., Thakur, V.K., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 27–77. [Google Scholar]

- Pahapale, G.J.; Tao, J.; Nikolic, M.; Gao, S.; Scarcelli, G.; Sun, S.X.; Romer, L.H.; Gracias, D.H. Directing Multicellular Organization by Varying the Aspect Ratio of Soft Hydrogel Microwells. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2104649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Tan, H.; Wei, J.; Yuan, H.; Li, S.; Yang, P.; Mi, H.; Liu, C.; Shen, C. Surface Modification of Super Arborized Silica for Flexible and Wearable Ultrafast-Response Strain Sensors with Low Hysteresis. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2301713. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, E.C.; Dhakal, S.; Amini, S.; Alhasan, R.; Fratzl, P.; Tree, D.R.; Morozova, S.; Hickey, R.J. Porous hierarchically ordered hydrogels demonstrating structurally dependent mechanical properties. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, P.; D’áVila, M.; Anand, R.; Moldenaers, P.; Van Puyvelde, P.; Bloemen, V. Insights on shear rheology of inks for extrusion-based 3D bioprinting. Bioprinting 2021, 22, e00129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; An, Y.; Zhao, X.; Li, M.; Zhang, J. Three-dimensional bioprinting of tissue-engineered skin: Biomaterials, fabrication techniques, challenging difficulties, and future directions: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 266, 131281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.B.; Anvari-Yazdi, A.F.; Duan, X.; Zimmerling, A.; Gharraei, R.; Sharma, N.K.; Sweilem, S.; Ning, L. Biomaterials/bioinks and extrusion bioprinting. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 28, 511–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanshen, Y. Engineering bio-inks for 3D bioprinting cell mechanical microenvironment. Int. J. Bioprinting 2022, 9, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martyts, A.; Sachs, D.; Hiebert, P.; Junker, H.; Robmann, S.; Hopf, R.; Steenbock, H.; Brinckmann, J.; Werner, S.; Giampietro, C.; et al. Biomechanical and biochemical changes in murine skin during development and aging. Acta Biomater. 2024, 186, 316–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Shi, K.; Yang, J.; Li, W.; Yu, Y.; Mi, Y.; Yao, T.; Ma, P.; Fan, D. 3D printing of recombinant collagen/chitosan methacrylate/nanoclay hydrogels loaded with Kartogenin nanoparticles for cartilage regeneration. Regen. Biomater. 2024, 11, rbae097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hospodiuk, M.; Dey, M.; Sosnoski, D.; Ozbolat, I.T. The bioink: A comprehensive review on bioprintable materials. Biotechnol. Adv. 2017, 35, 217–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.; Wu, Z.; Chu, H.; Wang, T.; Qiu, S.; Zhou, J.; Zhu, Q.; Liu, X.; Quan, D.; Bai, Y. Thiol-Rich Multifunctional Macromolecular Crosslinker for Gelatin-Norbornene-Based Bioprinting. Biomacromolecules 2021, 22, 2729–2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, L.; Zhang, Z.; Yuan, D.; Yu, M.; Min, J. Tissue engineering applications of recombinant human collagen: A review of recent progress. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1358246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudapati, H.; Torigoe, R.M.S.; Tahmasebifar, A.; Purushothaman, K.R.; Wyles, S. First-in-kind 3D bioprinted human skin model using recombinant human collagen. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2025, 317, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Qiu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Dai, Q.; Cao, X.; Shao, L.; Zhao, F. Autologous myokine-loaded pre-vascularized bioactive scaffold enhances bone augmentation. Compos. Part B Eng. 2025, 290, 111967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, S.; Hanselmann, C.; Gassmann, M.G.; Keller, U.A.D.; Born-Berclaz, C.; Chan, K.; Kan, Y.W.; Werner, S. Nrf2 transcription factor, a novel target of keratinocyte growth factor action which regulates gene expression and inflammation in the healing skin wound. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002, 22, 5492–5505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okkay, I.F.; Famurewa, A.; Bayram, C.; Okkay, U.; Mendil, A.S.; Sezen, S.; Ayaz, T.; Gecili, I.; Ozkaraca, M.; Senyayla, S.; et al. Arbutin abrogates cisplatin-induced hepatotoxicity via upregulating Nrf2/HO-1 and suppressing genotoxicity, NF-κB/iNOS/TNF-α and caspase-3/Bax/Bcl2 signaling pathways in rats. Toxicol. Res. 2024, 13, tfae075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghizadeh, F.; Hosseinimehr, S.J.; Zargari, M.; Malekshah, A.K.; Mirzaei, M.; Amiri, F.T. Alleviation of cisplatin-induced hepatotoxicity by gliclazide: Involvement of oxidative stress and caspase-3 activity. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2021, 9, e00788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsekoura, G.; Agathangelidis, A.; Kontandreopoulou, C.N.; Taliouraki, A.; Mporonikola, G.; Stavropoulou, M.; Diamantopoulos, P.T.; Viniou, N.A.; Aleporou, V.; Papassideri, I.; et al. Deregulation of Autophagy and Apoptosis in Patients with Myelodysplastic Syndromes: Implications for Disease Development and Progression. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2023, 45, 4135–4150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Boghdady, N.A.; El-Hakk, S.A.; Abd-Elmawla, M.A. The lncRNAs UCA1 and CRNDE target miR-145/TLR4/NF-κB/TNF-α axis in acetic acid-induced ulcerative colitis model: The beneficial role of 3,3-Diindolylmethane. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 121, 110541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, T.; Liu, X.; Kong, F.-Q.; Duan, Y.-Y.; Yee, A.L.; Kim, M.; Galzote, C.; Gilbert, J.A.; Quan, Z.-X. Age and Mothers: Potent Influences of Children’s Skin Microbiota. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2019, 139, 2497–2505.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, L.; Yao, R.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, W. Effect of bioink properties on printability and cell viability for 3D bioplotting of embryonic stem cells. Biofabrication 2016, 8, 035020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| RHC-I-MA:RHC-III-MA | Composite |

|---|---|

| 7:3 | RHC-MA-a |

| 9:1 | RHC-MA-b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, T.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, C.; Zhao, J.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, M. Bioprinted Recombinant Human-Collagen-Based In Vitro Skin Models for Assessing Effects of Nano-ZnO on Dermis. Gels 2025, 11, 977. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120977

Yu T, Xu Y, Zhang X, Zhu C, Zhao J, Yang Y, Jiang M. Bioprinted Recombinant Human-Collagen-Based In Vitro Skin Models for Assessing Effects of Nano-ZnO on Dermis. Gels. 2025; 11(12):977. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120977

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Ting, Yang Xu, Xinyue Zhang, Chenkai Zhu, Jianfeng Zhao, Yang Yang, and Min Jiang. 2025. "Bioprinted Recombinant Human-Collagen-Based In Vitro Skin Models for Assessing Effects of Nano-ZnO on Dermis" Gels 11, no. 12: 977. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120977

APA StyleYu, T., Xu, Y., Zhang, X., Zhu, C., Zhao, J., Yang, Y., & Jiang, M. (2025). Bioprinted Recombinant Human-Collagen-Based In Vitro Skin Models for Assessing Effects of Nano-ZnO on Dermis. Gels, 11(12), 977. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120977