κ-Carrageenan and Its Synergistic Blends: Next-Generation Food Gels

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Animal Gelatin: The Traditional Standard for Gels

- Melt-in-the-mouth perception: gelatin melts just below human body temperature, producing a characteristic sensory experience accompanied by rapid flavour and aroma release. This unique perception is particularly difficult to achieve with plant-based polymers.

- Thermally reversible gelation: gelatin gels are reversible, liquefying upon heating and re-forming upon cooling.

- Multifunctionality: a single biopolymer simultaneously provides gelling, thickening, water-binding, emulsifying, foaming, and film-forming capabilities.

- Customizability: commercial gelatin is available in a broad range of gel strengths and particle sizes, allowing fine-tuning for diverse industrial applications.

- Ease of use: gelatin readily gels within the natural pH range of most foods without requiring additional salts, sugars, or acids, unlike many plant-derived hydrocolloids.

3. Development of Gelatin Alternative from Polysaccharides

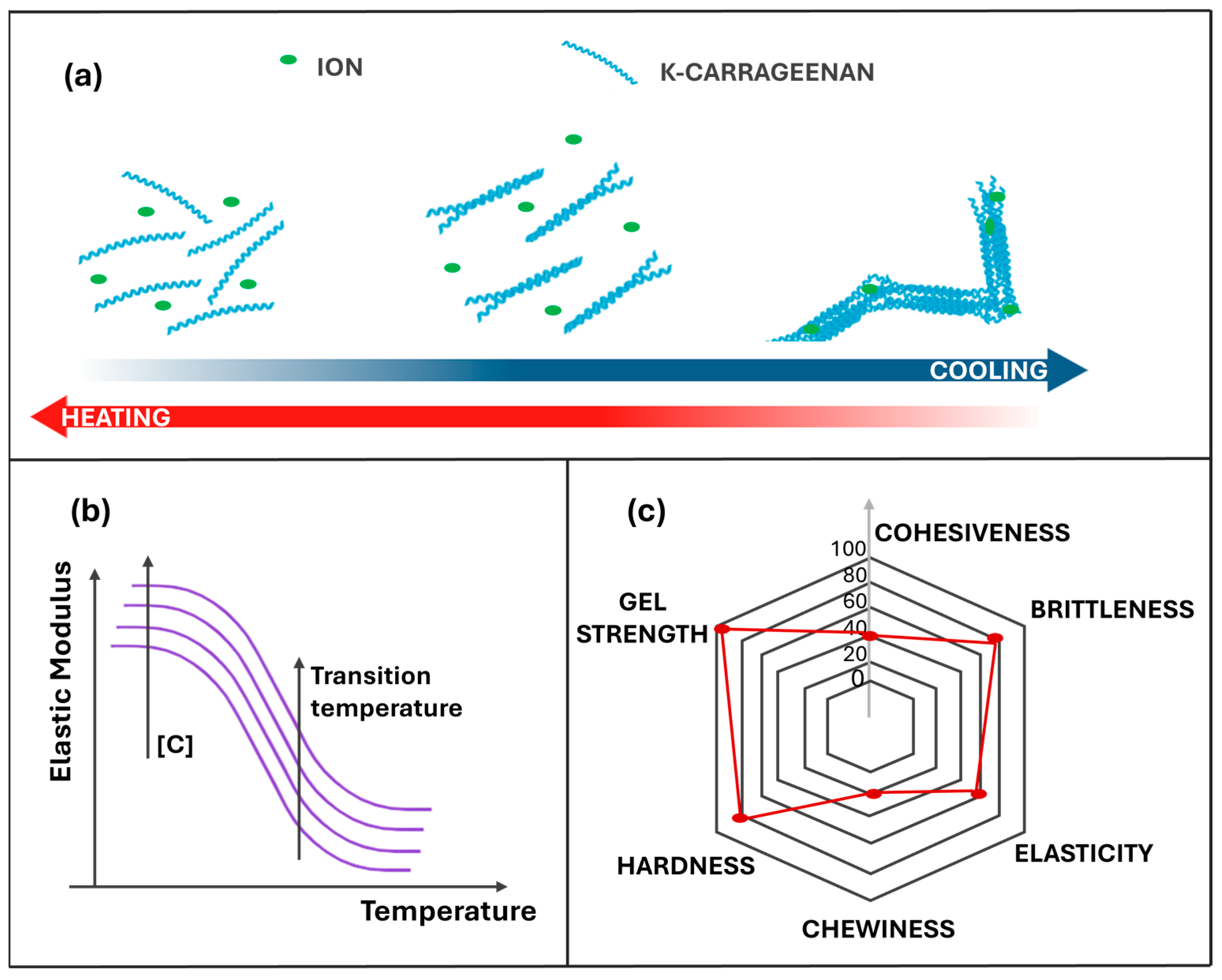

3.1. Carrageenan: Physicochemical and Functional Properties

3.1.1. Safety and Regulation of κ-Carrageenan-Carrageenan

3.1.2. Gel Strength and Application

3.2. κ-Carrageenan Gels in Complex Food Systems

4. Synergistic Combinations with Other Hydrocolloids

4.1. κ-Carrageenan and Locust Bean Gum

Gel Strength and Application

4.2. κ-Carrageenan and Konjac Glucomannan (KGM)

4.2.1. Safety and Regulation of Konjac Glucomannan

4.2.2. Gel Strength and Application

5. Other Potential Polysaccharide-Based Gelatin Alternatives

6. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Veis, A. The Physical Chemistry of Gelatin. Int. Rev. Connect. Tissue Res. 1965, 3, 113–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Masedunskas, A.; Willett, W.C.; Fontana, L. Vegetarian and vegan diets: Benefits and drawbacks. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3423–3439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alipal, J.; Mohd Pu’ad, N.A.S.; Lee, T.C.; Nayan, N.H.M.; Sahari, N.; Basri, H.; Idris, M.I.; Abdullah, H.Z. A review of gelatin: Properties, sources, process, applications, and commercialisation. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 42, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhailov, O.V. Gelatin as It Is: History and Modernity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Tu, Z.; Shangguan, X.; Sha, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; Bansal, N. Fish gelatin modifications: A comprehensive review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 86, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duconseille, A.; Astruc, T.; Quintana, N.; Meersman, F.; Sante-Lhoutellier, V. Gelatin structure and composition linked to hard capsule dissolution: A review. Food Hydrocoll. 2015, 43, 360–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Ishaq, A.; Regenstein, J.M.; Sahar, A.; Aadil, R.M.; Sameen, A.; Khan, M.I.; Alam, A. Valorization of animal by-products for gelatin extraction using conventional and green technologies: A comprehensive review. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2023, 15, 28355–28367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Food Additives and Nutrient Sources Added to Food (ANS); Mortensen, A.; Aguilar, F.; Crebelli, R.; Di Domenico, A.; Frutos, M.J.; Galtier, P.; Gott, D.; Gundert-Remy, U.; Lambré, C.; et al. Re-evaluation of konjac gum (E 425 i) and konjac glucomannan (E 425 ii) as food additives. EFSA J. 2017, 15, e04864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Goff, H.D.; Cui, S.W. Comparison of synergistic interactions of yellow mustard gum with locust bean gum or κ-carrageenan. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 132, 107804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dea, I.C.M.; Morrison, A. Chemistry and Interactions of Seed Galactomannans. Adv. Carbohydr. Chem. Biochem. 1975, 31, 241–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arda, E.; Kara, S.; Pekcan, Ö. Synergistic effect of the locust bean gum on the thermal phase transitions of κ-carrageenan gels. Food Hydrocoll. 2009, 23, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agoub, A.A.; Smith, A.M.; Giannouli, P.; Richardson, R.K.; Morris, E.R. “Melt-in-the-mouth” gels from mixtures of xanthan and konjac glucomannan under acidic conditions: A rheological and calorimetric study of the mechanism of synergistic gelation. Carbohydr. Polym. 2007, 69, 713–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Regenstein, J.M.; Lv, S.; Lu, J.; Jiang, S. An overview of gelatin derived from aquatic animals: Properties and modification. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 68, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestari, W.; Octavianti, F.; Jaswir, I.; Hendri, R. Plant-Based Substitutes for Gelatin. In Contemporary Management and Science Issues in the Halal Industry; Hassan, F., Osman, I., Kassim, E.S., Haris, B., Hassan, R., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 319–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, A.A.; Bhat, R. Gelatin alternatives for the food industry: Recent developments, challenges and prospects. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2008, 19, 644–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-M.; Nie, S.-P. The functional and nutritional aspects of hydrocolloids in foods. Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 53, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waraczewski, R.; Muszyński, S.; Sołowiej, B.G. An Analysis of the Plant- and Animal-Based Hydrocolloids as Byproducts of the Food Industry. Molecules 2022, 27, 8686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirsa, S.; Hafezi, K. Hydrocolloids: Structure, preparation method, and application in food industry. Food Chem. 2023, 399, 133967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benalaya, I.; Alves, G.; Lopes, J.; Silva, L.R. A Review of Natural Polysaccharides: Sources, Characteristics, Properties, Food, and Pharmaceutical Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez, B. Food Industrial Processes: Methods and Equipment; BoD—Books on Demand: Norderstedt, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Yuguchi, Y.; Thu Thuy, T.T.; Urakawa, H.; Kajiwara, K. Structural characteristics of carrageenan gels: Temperature and concentration dependence. Food Hydrocoll. 2002, 16, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zia, K.M.; Tabasum, S.; Nasif, M.; Sultan, N.; Aslam, N.; Noreen, A.; Zuber, M. A review on synthesis, properties and applications of natural polymer based carrageenan blends and composites. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 96, 282–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murayama, A.; Ichikawa, Y.; Kawabata, A. Sensory and rheological properties ofk -carrageenan gels mixed with locust bean gum, tara gum or guar gum. J. Texture Stud. 1995, 26, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalaby, E. Biological Activities and Application of Marine Polysaccharides; BoD—Books on Demand: Norderstedt, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z. Solubility of Polysaccharides; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lesnichaya, M.V.; Aleksandrova, G.P.; Sukhov, B.G.; Rokhin, A.V. Molecular-weight characteristics of galactomannan and carrageenan. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2013, 49, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myslabodski, D.E.; Stancioff, D.; Heckert, R.A. Effect of acid hydrolysis on the molecular weight of kappa carrageenan by GPC-LS. Carbohydr. Polym. 1996, 31, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo Spena, S.; Pasquino, R.; Sarrica, A.; Delmonte, M.; Yang, C.; Grizzuti, N. Kinetics of acid hydrolysis of k-Carrageenan by in situ rheological follow-up. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 144, 108953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udo, T.; Mummaleti, G.; Mohan, A.; Singh, R.K.; Kong, F. Current and emerging applications of carrageenan in the food industry. Food Res. Int. 2023, 173, 113369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Necas, J.; Bartosikova, L. Carrageenan: A review. Vet. Med. 2013, 58, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Food Additives and Nutrient Sources added to Food (ANS); Younes, M.; Aggett, P.; Aguilar, F.; Crebelli, R.; Filipič, M.; Frutos, M.J.; Galtier, P.; Gott, D.; Gundert-Remy, U.; et al. Re-evaluation of carrageenan (E 407) and processed Eucheuma seaweed (E 407a) as food additives. EFSA J. 2018, 16, e05238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berton, S.B.R.; De Jesus, G.A.M.; Sabino, R.M.; Monteiro, J.P.; Venter, S.A.S.; Bruschi, M.L.; Popat, K.C.; Matsushita, M.; Martins, A.F.; Bonafé, E.G. Properties of a commercial κ-carrageenan food ingredient and its durable superabsorbent hydrogels. Carbohydr. Res. 2020, 487, 107883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avallone, P.R.; Russo Spena, S.; Acierno, S.; Esposito, M.G.; Sarrica, A.; Delmonte, M.; Pasquino, R.; Grizzuti, N. Thermorheological Behavior of κ-Carrageenan Hydrogels Modified with Xanthan Gum. Fluids 2023, 8, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo Spena, S.; Grizzuti, N.; Tammaro, D. Linking processing parameters and rheology to optimize additive manufacturing of k-carrageenan gel systems. Gels 2022, 8, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo Spena, S.; Poli, L.; Grizzuti, N. The art of confectionery creams: Rheological insight across formulations. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2025, 41, 101217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, O.; Trudsoe, J. EFFECT OF OTHER HYDROCOLLOIDS ON THE TEXTURE OF KAPPA CARRAGEENAN GELS1. J. Texture Stud. 1980, 11, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.; Zou, Y.; Cui, B.; Fang, Y.; Lu, L.; Xu, D. Influence of cyclodextrins on the gelation behavior of κ-carrageenan/konjac glucomannan composite gel. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 120, 106927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, G.; Morris, E.R.; Rees, D.A. Role of double helices in carrageenan gelation: The domain model. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1980, 4, 152–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishinari, K.; Watase, M. Effects of sugars and polyols on the gel-sol transition of kappa-carrageenan gels. Thermochim. Acta 1992, 206, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Marhoobi, I.M.; Kasapis, S. Further evidence of the changing nature of biopolymer networks in the presence of sugar. Carbohydr. Res. 2005, 340, 771–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasapis, S.; Al-Marhoobi, I.M.; Deszczynski, M.; Mitchell, J.R.; Abeysekera, R. Gelatin vs. Polysaccharide in Mixture with Sugar. Biomacromolecules 2003, 4, 1142–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stenner, R.; Matubayasi, N.; Shimizu, S. Gelation of carrageenan: Effects of sugars and polyols. Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 54, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ako, K. Influence of elasticity on the syneresis properties of κ-carrageenan gels. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 115, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, E.L.; Norton, I.T.; Mills, T.B. Comparing the viscoelastic properties of gelatin and different concentrations of kappa-carrageenan mixtures for additive manufacturing applications. J. Food Eng. 2019, 246, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, M.A.F.; Faria, B.; Moraes, I.C.F.; Hilliou, L. Hybrid Carrageenans Versus Kappa–Iota-Carrageenan Blends: A Comparative Study of Hydrogel Elastic Properties. Gels 2025, 11, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puvanenthiran, A.; Goddard, S.J.; Mckinnon, I.R.; Augustin, M.A. Milk-based Gels Made with κ-Carrageenan. J. Food Sci. 2003, 68, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drohan, D.D.; Tziboula, A.; McNulty, D.; Horne, D.S. Milk protein-carrageenan interactions. Food Hydrocoll. 1997, 11, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakenfull, D.; Miyoshi, E.; Nishinari, K.; Scott, A. Rheological and thermal properties of milk gels formed with k-carrageenan. I. Sodium caseinate. Food Hydrocoll. 1999, 13, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Additives and Products or Substances Used in Animal Feed (FEEDAP); Bampidis, V.; Azimonti, G.; de Lourdes Bastos, M.; Christensen, H.; Dusemund, B.; Durjava, M.F.; Kouba, M.; López-Alonso, M.; López Puente, S.; et al. Safety and efficacy of a feed additive consisting of locust bean gum for all animal species (Dupont Nutrition and Health). EFSA J. 2022, 20, e07435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakia, P.A.; Blecker, C.; Robert, C.; Wathelet, B.; Paquot, M. Composition and physicochemical properties of locust bean gum extracted from whole seeds by acid or water dehulling pre-treatment. Food Hydrocoll. 2008, 22, 807–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barak, S.; Mudgil, D. Locust bean gum: Processing, properties and food applications—A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2014, 66, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Market Research Future: Industry Analysis Report, Business Consulting and Research (Industry Estimate). Available online: https://www.marketresearchfuture.com (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Tanaka, R.; Hatakeyama, T.; Hatakeyama, H. Formation of locust bean gum hydrogel by freezing–thawing. Polym. Int. 1998, 45, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, P.H.; Norton, I.T. Gelation Behavior of Concentrated Locust Bean Gum Solutions. Macromolecules 1998, 31, 1575–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaisford, S.E.; Harding, S.E.; Mitchell, J.R.; Bradley, T.D. A comparison between the hot and cold water soluble fractions of two locust bean gum samples. Carbohydr. Polym. 1986, 6, 423–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, P.; Morris, V.J.; Miles, M.J.; Brownsey, G.J. Comparative studies of the mechanical properties of mixed gels formed by kappa carrageenan and tara gum or carob gum. Food Hydrocoll. 1986, 1, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochas, C.; Rinaudo, M.; Landry, S. Role of the molecular weight on the mechanical properties of kappa carrageenan gels. Carbohydr. Polym. 1990, 12, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murayama, A.; Osako, S.; Kawabata, A. Changes in the Rheological Properties of κ-Carrageenan Gels after Adding Locust Bean Gum. J. Home Econ. Jpn. 1990, 41, 133–136. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, P.B.; Gonçalves, M.P.; Doublier, J.L. Influence of locust bean gum on the rheological properties of kappa-carrageenan systems in the vicinity of the gel point. Carbohydr. Polym. 1993, 22, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo Spena, S.; Pasquino, R.; Grizzuti, N. K-Carrageenan/Locust Bean Gum Gels for Food Applications—A Critical Study on Potential Alternatives to Animal-Based Gelatin. Foods 2024, 13, 2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Sheng, Z.; Zhou, H.; He, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Luo, J. Improvement of casein/κ-carrageenan composite gel properties: Role of locust bean gum concentration. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 158, 110547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Yokoyama, W.; Chen, L.; Liu, F.; Chen, M.; Zhong, F. Characterization and physicochemical properties analysis of konjac glucomannan: Implications for structure-properties relationships. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 120, 106818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F. Modifications of konjac glucomannan for diverse applications. Food Chem. 2018, 256, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.A.; Clegg, S.M.; Langdon, M.J.; Nishinari, K.; Piculell, L. Investigation of the gelation mechanism in .kappa.-carrageenan/konjac mannan mixtures using differential scanning calorimetry and electron spin resonance spectroscopy. Macromolecules 1993, 26, 5441–5446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, K.; Guo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, G.; Qiao, D.; Jiang, F.; Zhang, B. Mechanism for the synergistic gelation of konjac glucomannan and κ-carrageenan. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 277, 134423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Zhou, D.; Guo, Q.; Liu, C. Textural and structural properties of a κ-carrageenan–konjac gum mixed gel: Effects of κ-carrageenan concentration, mixing ratio, sucrose and Ca2+ concentrations and its application in milk pudding. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 3021–3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penroj, P.; Mitchell, J.R.; Hill, S.E.; Ganjanagunchorn, W. Effect of konjac glucomannan deacetylation on the properties of gels formed from mixtures of kappa carrageenan and konjac glucomannan. Carbohydr. Polym. 2005, 59, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Yu, S.; Liang, H.; Eid, M.; Li, B.; Li, J.; Mao, J. An innovative konjac glucomannan/κ-carrageenan mixed tensile gel. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 5067–5074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo Spena, S.; Visone, B.; Grizzuti, N. An engineering approach to the 3D printing of K-Carrageenan/konjac glucomannan hydrogels. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 59, 4122–4133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagal-Kestwal, D.R.; Pan, M.; Chiang, B.-H. Properties and Applications of Gelatin, Pectin, and Carrageenan Gels. In Bio Monomers for Green Polymeric Composite Materials; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2019; pp. 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaee, M.; Ait Aider-Kaci, F.; Aider, M. Effects of Hydrocolloid Agar, Gelatin, Pectin, and Xanthan on Physicochemical and Rheological Properties of Pickering Emulsions Stabilized by Canola Protein Microgel as a Potential Animal Fat Replacer. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 2, 1681–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-J.; Wang, L. Structures and Properties of Commercial Maltodextrins from Corn, Potato, and Rice Starches. Starch Stärke 2000, 52, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, M.; Yang, D.; Lai, S.; Yang, H. Rheological properties of xanthan-modified fish gelatin and its potential to replace mammalian gelatin in low-fat stirred yogurt. LWT 2021, 147, 111643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marfil, P.H.M.; Anhê, A.C.B.M.; Telis, V.R.N. Texture and Microstructure of Gelatin/Corn Starch-Based Gummy Confections. Food Biophys. 2012, 7, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| System/Hydrocolloid Combination | Typical Composition & Processing Conditions | Key Structural/Rheological Features | Sensory/Textural Attributes vs. Gelatin | Main Advantages/Limitations | Representative Food Applications | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| κ-C | κ-C ≈ 2–5 wt%; K+/Na+ as counterions; pH ≈ 6–7; heating above coil–helix transition and cooling under quiescent conditions | Strong, ion-dependent, thermo-reversible gels; G′ increases with κ-C and K+ concentration; porous, brittle network; high and | Higher firmness than 6.67% gelatin; brittle fracture, limited deformability; lacks melt-in-the-mouth behaviour due to high melting temperature | + Strong gels at relatively low polymer level; good water binding and stability. − Pronounced brittleness and syneresis; high melting temperature; limited elastic recovery | Water-based dessert gels, milk desserts, confectionery inclusions, 3D-printing of simple shapes | [20,29,30,31,32,40,52] |

| κ-C/LBG | κ-C ≈ 1–2 wt%; LBG/κ-C ≈ 1:2–1:10; low–moderate KCl/NaCl (≈0.25–1%); heating–cooling under quiescent conditions | Synergistic gelation: LBG promotes κ-C helix formation and aggregation; higher G′ at lower κ-C level; sharper sol–gel transition; denser network; reduced syneresis | Higher fracture stress and water retention than κ-C alone; more ductile behaviour at κ-C:LBG ≈ 7:3–6:4; however, strain and cohesiveness remain lower than gelatin; melt-in-mouth still not reproduced ( ≈ 43–70 °C) | + Synergy allows reduction in κ-C; improved ductility, reduced syneresis, better water holding; widely used, label-friendly system. − Narrow optimal composition and salt window; thermal behaviour still far from gelatin; incomplete match of elasticity and resilience | Confectionery-type dessert gels, dairy and dairy analogues, thickened creams, 3D-printable gels and structured foods | [46,52,54,55,56,57,59] |

| κ-C/KGM | κ-C typically ≤ 1–1.5 wt%; KGM added at comparable or slightly higher level; pH ≈ neutral; heating–cooling; possible deacetylation of KGM for thermally irreversible gels | Stronger synergy than κ-C/LBG: KGM promotes κ-C coil–helix transition, stabilises helices by adsorption, and yields thick helical bundles; dense, homogeneous network; higher G′ and improved fracture properties at lower κ-C | Elastic, cohesive gels with high water retention; more homogeneous texture than κ-C alone; melt-in-mouth behaviour improved but still limited by relatively high melting temperature | + High water binding and viscosity; strong reinforcement of κ-C network; possibility of tailoring reversibility via KGM acetylation. − Process-sensitive (pH, ionic strength, KGM deacetylation); regulatory and consumer perception aspects for konjac; still not fully equivalent to gelatin | Milk puddings and dairy analogues, high-fibre gels, structured soft foods, potential 3D-printed systems | [60,61,62,63,64,65,67,69,70,71,72] |

| κ-C/starches, fibres, other polysaccharide (xanthan, pectin, etc…) | κ-C combined with starch, dietary fibres, xanthan or pectin; often high-solid systems (sugar, acids, flavours); thermal processing typical of confectionery/desserts | Mixed networks or phase-separated structures; κ-C provides gel backbone; starch/fibres contribute viscosity, opacity, and water binding; microstructure and viscoelasticity strongly formulation-dependent | Can approach gelatin-like firmness and chewiness in high-solid matrices; mouthfeel often less elastic and more pasty or short; melting behaviour broader and less sharp than gelatin | + Wide formulation flexibility; possibility to tailor texture through multi-component design; improved nutritional profile (fibres). − Complex, application-specific optimisation; thermal behaviour and breakdown in mouth rarely match gelatin | Jelly candies, fruit gels, reduced-sugar confectionery, bakery fillings, hybrid dairy analogues | [30,32,36,37,38,39,71] |

| Gellan gum (HA, LA and blends) | HA, LA or partially deacylated gellan; total solids ≈ 10–20%; cations (Ca2+, Na+, etc.); heating and controlled cooling | Gel texture tunable from soft/elastic (HA) to firm/brittle (LA); blends or partial deacylation give intermediate properties; high set and melt temperatures; strong, transparent gels | In suitable formulations, partially deacylated gellan can approximate gelatin-like brittleness, elasticity and cohesiveness in water-based dessert gels; however, melting window remains broader and at higher temperature than gelatin | + Very versatile, robust gels; good thermal stability and rapid setting; suitable for hot climates. − Sensory breakdown and melt-in-mouth perception still differ from gelatin; ion-sensitive; sometimes perceived as too brittle | Water gels and desserts, beverages, confectionery, structured sauces, plant-based dairy analogues | [9,12,17] |

| Other plant-based hydrocolloids (xanthan-galactomannan, pectin, mixed systems) | Various combinations (xanthan/LBG, HM or LM pectin, fibres, proteins); pH, sugar and Ca2+ content tuned to application | From weak, spreadable gels to firm elastic networks; cold-set or heat-set depending on system; strong control of syneresis and water activity in high-solid products | Often able to mimic specific aspects of gelatin (e.g., spreadability, cuttability, chewiness) in narrow formulation windows; thermal reversibility and narrow melting range usually not matched | + Clean-label, often high-fibre; good control of water activity and stability; adaptable to many matrices. − Typically case-by-case optimisation; rarely able to reproduce full sensory profile of gelatin | Jams, fruit preparations, bakery fillings, meat and dairy analogues, high-fibre desserts | [14,15,16,21] |

| κ-C based systems for 3D printed foods | κ-C alone or in synergy (LBG, KGM, starch, fibres); concentration and temperature selected to ensure yield stress and shape fidelity; extrusion-based printing | Clear yield stress and shear-thinning behaviour; rapid structure recovery after extrusion; thermo-reversible network enables post-printing setting; microstructure tunable with cooling rate and composition | Texture post-printing ranges from soft/creamy to firm gels; mechanical properties can approach gelatin-based references, though cohesiveness and melt-in-mouth are still lower | + Good printability and shape retention; compatibility with flavours, colours and active ingredients; potential for personalised nutrition. − Narrow processing window (temperature, concentration); long-term stability and sensory attributes still under development | 3D-printed snacks, desserts, personalised gels for children/elderly, prototype plant-based confectionery | [29,40,71] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Russo Spena, S.; Grizzuti, N. κ-Carrageenan and Its Synergistic Blends: Next-Generation Food Gels. Gels 2025, 11, 976. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120976

Russo Spena S, Grizzuti N. κ-Carrageenan and Its Synergistic Blends: Next-Generation Food Gels. Gels. 2025; 11(12):976. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120976

Chicago/Turabian StyleRusso Spena, Simona, and Nino Grizzuti. 2025. "κ-Carrageenan and Its Synergistic Blends: Next-Generation Food Gels" Gels 11, no. 12: 976. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120976

APA StyleRusso Spena, S., & Grizzuti, N. (2025). κ-Carrageenan and Its Synergistic Blends: Next-Generation Food Gels. Gels, 11(12), 976. https://doi.org/10.3390/gels11120976