The Vacuolar Protein 8 (Vac8) Homolog in Cryptococcus neoformans Impacts Stress Responses and Virulence Traits Through Conserved and Unique Roles

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strains, Cell Lines, and Growth Conditions

2.2. In Silico Sequence Analysis

2.3. Drug Susceptibility Assays

2.4. Stress Plate Phenotyping

2.5. Fungal Genomic Manipulation

2.6. Titan Cell Induction and Quantification

2.7. Vacuole Induction and FM4-64 Staining

2.8. Macrophage Uptake Assay

2.9. Mouse Virulence Study

2.10. Histology

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Deletion of Both PFA4 and CNAG_00354 Causes Vacuolar Fragmentation

3.2. CNAG_00354 Is a True Ortholog of Saccharomyces cerevisiae VAC8

indicates predicted myristylation site,

indicates predicted myristylation site,  indicates predicted palmitoylation site, green ovals represent armadillo repeat regions, and blue hexagons represent predicted disorder regions. (D) AlphaFold predictions of C. neoformans (AlphaFold ID: AF-J9VIT9-F1), S. cerevisiae (AlphaFold ID: AF-P39968-F1), and C. albicans (AlphaFold ID: AF-Q59MN0-F1) Vac8.

indicates predicted palmitoylation site, green ovals represent armadillo repeat regions, and blue hexagons represent predicted disorder regions. (D) AlphaFold predictions of C. neoformans (AlphaFold ID: AF-J9VIT9-F1), S. cerevisiae (AlphaFold ID: AF-P39968-F1), and C. albicans (AlphaFold ID: AF-Q59MN0-F1) Vac8.

indicates predicted myristylation site,

indicates predicted myristylation site,  indicates predicted palmitoylation site, green ovals represent armadillo repeat regions, and blue hexagons represent predicted disorder regions. (D) AlphaFold predictions of C. neoformans (AlphaFold ID: AF-J9VIT9-F1), S. cerevisiae (AlphaFold ID: AF-P39968-F1), and C. albicans (AlphaFold ID: AF-Q59MN0-F1) Vac8.

indicates predicted palmitoylation site, green ovals represent armadillo repeat regions, and blue hexagons represent predicted disorder regions. (D) AlphaFold predictions of C. neoformans (AlphaFold ID: AF-J9VIT9-F1), S. cerevisiae (AlphaFold ID: AF-P39968-F1), and C. albicans (AlphaFold ID: AF-Q59MN0-F1) Vac8.

| Protein Name | Cellular Function | Present in C. neoformans | E-Value | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nvj1p (YHR195W) | Piecemeal microautophagy of the nucleus | No | [38,39] | |

| Vac17p (YCL063W) | Binding to Vac8 and Myo2 complex for vacuole inheritance | No | [38] | |

| Atg13p (YPR185W) | Required for cytoplasm-to-vacuole (Cvt) pathway and autophagy | No * | [38] | |

| Tco89p (YPL180W) | TORC complex subunit | No | [40] | |

| Vid21p (YDR359C) | NuA4 histone acetyltransferase complex subunit | Yes CNAG_01591 | 7 × 10−10 | [40] |

| Vab2p (YEL005C) | Vac8p binding | No | [40,41] | |

| Tao3p (YIL129C) | Involved in cell morphogenesis and proliferation | Yes CNAG_03622 | 1 × 10−79 | [40] |

3.3. Deletion of VAC8 Affects Vacuolar Fusion

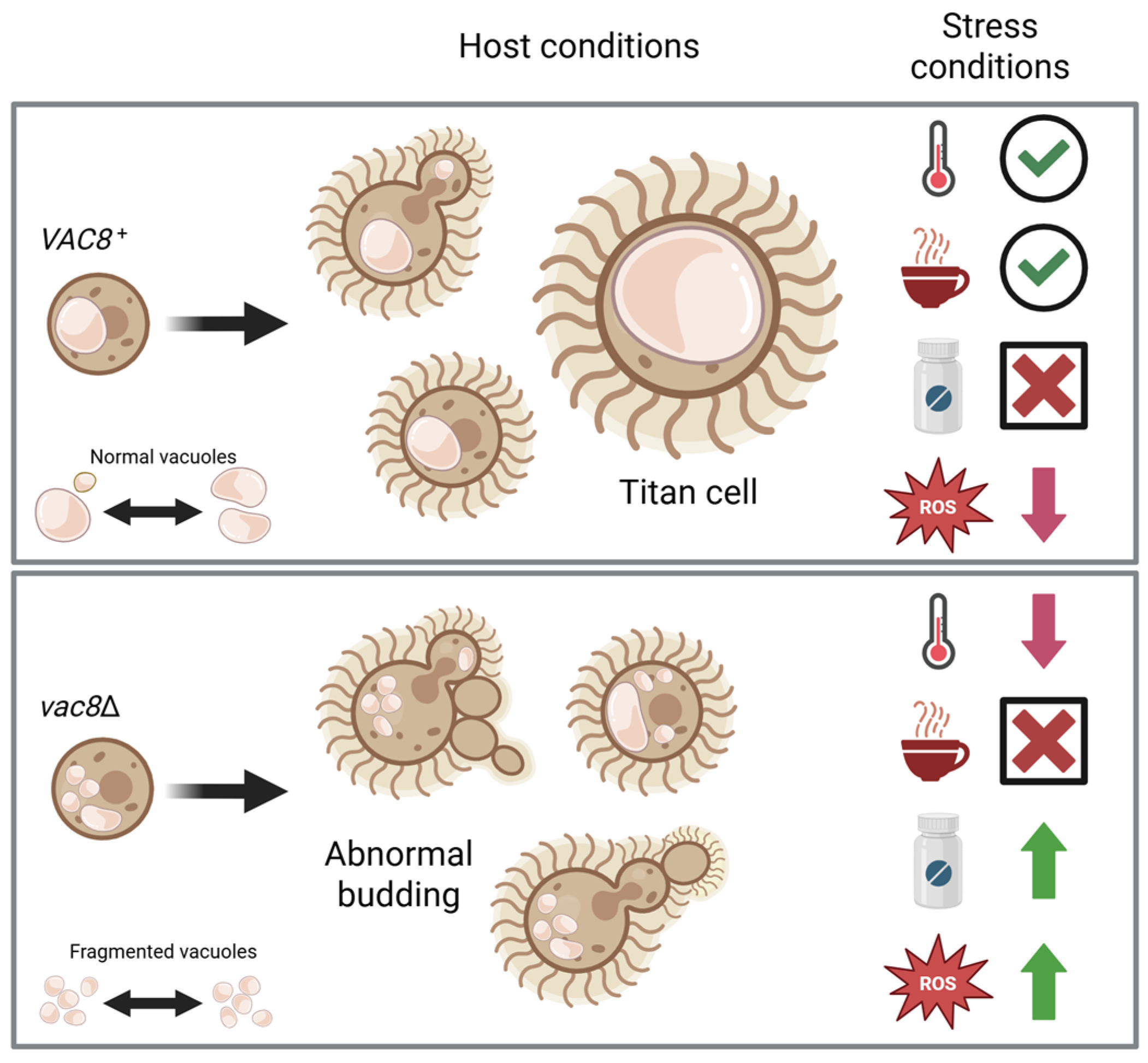

3.4. Loss of VAC8 Is Associated with Growth Defects Under Various Cell Stresses

3.5. Main Virulence Factors Are Unaffected in vac8Δ Mutants

3.6. Vac8Δ Mutants Show Aberrant Budding and Impairment in Titanization

3.7. Loss of VAC8 Causes Decreased Susceptibility to Fluconazole

3.8. Infection with vac8Δ Does Not Alter Disease Outcome in a Murine Model

3.9. Infection with vac8Δ Alters the Lung Environment Despite Not Impacting Disease Progression

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Denning, D.W. Global incidence and mortality of severe fungal disease. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, e428–e438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowen, L.E. The evolution of fungal drug resistance: Modulating the trajectory from genotype to phenotype. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2008, 6, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bermas, A.; Geddes-McAlister, J. Combatting the evolution of antifungal resistance in Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol. Microbiol. 2020, 114, 721–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, I.M.B.; Cortez, A.C.A.; de Souza, E.S.; Pinheiro, S.B.; de Souza Oliveira, J.G.; Sadahiro, A.; Cruz, K.S.; Matsuura, A.B.J.; Melhem, M.S.C.; Frickmann, H.; et al. Investigation of fluconazole heteroresistance in clinical and environmental isolates of Cryptococcus neoformans complex and Cryptococcus gattii complex in the state of Amazonas, Brazil. Med. Mycol. 2022, 60, myac005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajasingham, R.; Govender, N.P.; Jordan, A.; Loyse, A.; Shroufi, A.; Denning, D.W.; Meya, D.B.; Chiller, T.M.; Boulware, D.R. The global burden of HIV-associated cryptococcal infection in adults in 2020: A modelling analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 1748–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana-Sosa, S.; Matos-Perdomo, E.; Ayra-Plasencia, J.; Machin, F. A Yeast Mitotic Tale for the Nucleus and the Vacuoles to Embrace. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Veses, V.; Richards, A.; Gow, N.A. Vacuoles and fungal biology. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2008, 11, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popelka, H.; Klionsky, D.J. The emerging significance of Vac8, a multi-purpose armadillo-repeat protein in yeast. Autophagy 2025, 21, 913–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cheong, H.; Yorimitsu, T.; Reggiori, F.; Legakis, J.E.; Wang, C.W.; Klionsky, D.J. Atg17 regulates the magnitude of the autophagic response. Mol. Biol. Cell 2005, 16, 3438–3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Johnston, D.A.; Eberle, K.E.; Sturtevant, J.E.; Palmer, G.E. Role for endosomal and vacuolar GTPases in Candida albicans pathogenesis. Infect. Immun. 2009, 77, 2343–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liu, X.; Hu, G.; Panepinto, J.; Williamson, P.R. Role of a VPS41 homologue in starvation response, intracellular survival and virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol. Microbiol. 2006, 61, 1132–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, G.E.; Kelly, M.N.; Sturtevant, J.E. The Candida albicans vacuole is required for differentiation and efficient macrophage killing. Eukaryot. Cell 2005, 4, 1677–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Erickson, T.; Liu, L.; Gueyikian, A.; Zhu, X.; Gibbons, J.; Williamson, P.R. Multiple virulence factors of Cryptococcus neoformans are dependent on VPH1. Mol. Microbiol. 2001, 42, 1121–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilty, J.; Smulian, A.G.; Newman, S.L. The Histoplasma capsulatum vacuolar ATPase is required for iron homeostasis, intracellular replication in macrophages and virulence in a murine model of histoplasmosis. Mol. Microbiol. 2008, 70, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Roetzer, A.; Gratz, N.; Kovarik, P.; Schuller, C. Autophagy supports Candida glabrata survival during phagocytosis. Cell. Microbiol. 2010, 12, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Denham, S.T.; Brammer, B.; Chung, K.Y.; Wambaugh, M.A.; Bednarek, J.M.; Guo, L.; Moreau, C.T.; Brown, J.C.S. A dissemination-prone morphotype enhances extrapulmonary organ entry by Cryptococcus neoformans. Cell Host Microbe 2022, 30, 1382–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Trevijano-Contador, N.; Roselletti, E.; Garcia-Rodas, R.; Vecchiarelli, A.; Zaragoza, O. Role of IL-17 in Morphogenesis and Dissemination of Cryptococcus neoformans during Murine Infection. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sabiiti, W.; Robertson, E.; Beale, M.A.; Johnston, S.A.; Brouwer, A.E.; Loyse, A.; Jarvis, J.N.; Gilbert, A.S.; Fisher, M.C.; Harrison, T.S.; et al. Efficient phagocytosis and laccase activity affect the outcome of HIV-associated cryptococcosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2014, 124, 2000–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alanio, A.; Desnos-Ollivier, M.; Dromer, F. Dynamics of Cryptococcus neoformans-macrophage interactions reveal that fungal background influences outcome during cryptococcal meningoencephalitis in humans. MBio 2011, 2, e00158-11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hansakon, A.; Mutthakalin, P.; Ngamskulrungroj, P.; Chayakulkeeree, M.; Angkasekwinai, P. Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii clinical isolates from Thailand display diverse phenotypic interactions with macrophages. Virulence 2019, 10, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Santiago-Tirado, F.H.; Peng, T.; Yang, M.; Hang, H.C.; Doering, T.L. A Single Protein S-acyl Transferase Acts through Diverse Substrates to Determine Cryptococcal Morphology, Stress Tolerance, and Pathogenic Outcome. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1004908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Roth, A.F.; Wan, J.; Bailey, A.O.; Sun, B.; Kuchar, J.A.; Green, W.N.; Phinney, B.S.; Yates, J.R., 3rd; Davis, N.G. Global analysis of protein palmitoylation in yeast. Cell 2006, 125, 1003–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Beck, J.R.; Fung, C.; Straub, K.W.; Coppens, I.; Vashisht, A.A.; Wohlschlegel, J.A.; Bradley, P.J. A Toxoplasma palmitoyl acyl transferase and the palmitoylated armadillo repeat protein TgARO govern apical rhoptry tethering and reveal a critical role for the rhoptries in host cell invasion but not egress. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Subramanian, K.; Dietrich, L.E.; Hou, H.; LaGrassa, T.J.; Meiringer, C.T.; Ungermann, C. Palmitoylation determines the function of Vac8 at the yeast vacuole. J. Cell Sci. 2006, 119 Pt 12, 2477–2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, K.; Cox, G.M.; Litvintseva, A.P.; Mylonakis, E.; Malliaris, S.D.; Benjamin, D.K., Jr.; Giles, S.S.; Mitchell, T.G.; Casadevall, A.; Perfect, J.R.; et al. Cryptococcus neoformans alpha strains preferentially disseminate to the central nervous system during coinfection. Infect. Immun. 2005, 73, 4922–4933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ning, W.; Jiang, P.; Guo, Y.; Wang, C.; Tan, X.; Zhang, W.; Peng, D.; Xue, Y. GPS-Palm: A deep learning-based graphic presentation system for the prediction of S-palmitoylation sites in proteins. Brief. Bioinform. 2021, 22, 1836–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bologna, G.; Yvon, C.; Duvaud, S.; Veuthey, A.L. N-Terminal myristoylation predictions by ensembles of neural networks. Proteomics 2004, 4, 1626–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winski, C.J.; Qian, Y.; Mobashery, S.; Santiago-Tirado, F.H. An Atypical ABC Transporter Is Involved in Antifungal Resistance and Host Interactions in the Pathogenic Fungus Cryptococcus neoformans. MBio 2022, 13, e0153922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Spencer, G.W.K.; Chua, S.M.H.; Erpf, P.E.; Wizrah, M.S.I.; Dyba, T.G.; Condon, N.D.; Fraser, J.A. Broadening the spectrum of fluorescent protein tools for use in the encapsulated human fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2020, 138, 103365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upadhya, R.; Lam, W.C.; Maybruck, B.T.; Donlin, M.J.; Chang, A.L.; Kayode, S.; Ormerod, K.L.; Fraser, J.A.; Doering, T.L.; Lodge, J.K. A fluorogenic C. neoformans reporter strain with a robust expression of m-cherry expressed from a safe haven site in the genome. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2017, 108, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Huang, M.Y.; Joshi, M.B.; Boucher, M.J.; Lee, S.; Loza, L.C.; Gaylord, E.A.; Doering, T.L.; Madhani, H.D. Short homology-directed repair using optimized Cas9 in the pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans enables rapid gene deletion and tagging. Genetics 2022, 220, iyab180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Stempinski, P.R.; Goughenour, K.D.; du Plooy, L.M.; Alspaugh, J.A.; Olszewski, M.A.; Kozubowski, L. The Cryptococcus neoformans Flc1 Homologue Controls Calcium Homeostasis and Confers Fungal Pathogenicity in the Infected Hosts. MBio 2022, 13, e0225322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Weisman, L.S. Organelles on the move: Insights from yeast vacuole inheritance. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006, 7, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inglis, D.O.; Skrzypek, M.S.; Liaw, E.; Moktali, V.; Sherlock, G.; Stajich, J.E. Literature-based gene curation and proposed genetic nomenclature for cryptococcus. Eukaryot. Cell 2014, 13, 878–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Park, J.; Kim, H.I.; Jeong, H.; Lee, M.; Jang, S.H.; Yoon, S.Y.; Kim, H.; Park, Z.Y.; Jun, Y.; Lee, C. Quaternary structures of Vac8 differentially regulate the Cvt and PMN pathways. Autophagy 2020, 16, 991–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Harris, J.R.; Lockhart, S.R.; Sondermeyer, G.; Vugia, D.J.; Crist, M.B.; D’Angelo, M.T.; Sellers, B.; Franco-Paredes, C.; Makvandi, M.; Smelser, C.; et al. Cryptococcus gattii infections in multiple states outside the US Pacific Northwest. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013, 19, 1620–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kim, H.; Park, J.; Kim, H.; Ko, N.; Park, J.; Jang, E.; Yoon, S.Y.; Diaz, J.A.R.; Lee, C.; Jun, Y. Structures of Vac8-containing protein complexes reveal the underlying mechanism by which Vac8 regulates multiple cellular processes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2211501120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pan, X.; Roberts, P.; Chen, Y.; Kvam, E.; Shulga, N.; Huang, K.; Lemmon, S.; Goldfarb, D.S. Nucleus-vacuole junctions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae are formed through the direct interaction of Vac8p with Nvj1p. Mol. Biol. Cell 2000, 11, 2445–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tang, F.; Peng, Y.; Nau, J.J.; Kauffman, E.J.; Weisman, L.S. Vac8p, an armadillo repeat protein, coordinates vacuole inheritance with multiple vacuolar processes. Traffic 2006, 7, 1368–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John Peter, A.T.; Lachmann, J.; Rana, M.; Bunge, M.; Cabrera, M.; Ungermann, C. The BLOC-1 complex promotes endosomal maturation by recruiting the Rab5 GTPase-activating protein Msb3. J. Cell Biol. 2013, 201, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Benedict, K.; Jackson, B.R.; Chiller, T.; Beer, K.D. Estimation of Direct Healthcare Costs of Fungal Diseases in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019, 68, 1791–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Banerjee, S.; Kane, P.M. Regulation of V-ATPase Activity and Organelle pH by Phosphatidylinositol Phosphate Lipids. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zaragoza, O. Basic principles of the virulence of Cryptococcus. Virulence 2019, 10, 490–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Casadevall, A.; Coelho, C.; Cordero, R.J.B.; Dragotakes, Q.; Jung, E.; Vij, R.; Wear, M.P. The capsule of Cryptococcus neoformans. Virulence 2019, 10, 822–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen, S.C.; Muller, M.; Zhou, J.Z.; Wright, L.C.; Sorrell, T.C. Phospholipase activity in Cryptococcus neoformans: A new virulence factor? J. Infect. Dis. 1997, 175, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Rodas, R.; Cordero, R.J.; Trevijano-Contador, N.; Janbon, G.; Moyrand, F.; Casadevall, A.; Zaragoza, O. Capsule growth in Cryptococcus neoformans is coordinated with cell cycle progression. MBio 2014, 5, e00945-14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kelliher, C.M.; Leman, A.R.; Sierra, C.S.; Haase, S.B. Investigating Conservation of the Cell-Cycle-Regulated Transcriptional Program in the Fungal Pathogen, Cryptococcus neoformans. PLoS Genet. 2016, 12, e1006453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hommel, B.; Mukaremera, L.; Cordero, R.J.B.; Coelho, C.; Desjardins, C.A.; Sturny-Leclere, A.; Janbon, G.; Perfect, J.R.; Fraser, J.A.; Casadevall, A.; et al. Titan cells formation in Cryptococcus neoformans is finely tuned by environmental conditions and modulated by positive and negative genetic regulators. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1006982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dambuza, I.M.; Drake, T.; Chapuis, A.; Zhou, X.; Correia, J.; Taylor-Smith, L.; LeGrave, N.; Rasmussen, T.; Fisher, M.C.; Bicanic, T.; et al. The Cryptococcus neoformans Titan cell is an inducible and regulated morphotype underlying pathogenesis. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1006978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Trevijano-Contador, N.; de Oliveira, H.C.; Garcia-Rodas, R.; Rossi, S.A.; Llorente, I.; Zaballos, A.; Janbon, G.; Arino, J.; Zaragoza, O. Cryptococcus neoformans can form titan-like cells in vitro in response to multiple signals. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1007007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zaragoza, O.; Nielsen, K. Titan cells in Cryptococcus neoformans: Cells with a giant impact. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2013, 16, 409–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zafar, H.; Altamirano, S.; Ballou, E.R.; Nielsen, K. A titanic drug resistance threat in Cryptococcus neoformans. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2019, 52, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shapiro, R.S.; Robbins, N.; Cowen, L.E. Regulatory circuitry governing fungal development, drug resistance, and disease. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2011, 75, 213–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Maebashi, K.; Kudoh, M.; Nishiyama, Y.; Makimura, K.; Uchida, K.; Mori, T.; Yamaguchi, H. A novel mechanism of fluconazole resistance associated with fluconazole sequestration in Candida albicans isolates from a myelofibrosis patient. Microbiol. Immunol. 2002, 46, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulshan, K.; Moye-Rowley, W.S. Vacuolar import of phosphatidylcholine requires the ATP-binding cassette transporter Ybt1. Traffic 2011, 12, 1257–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Khandelwal, N.K.; Kaemmer, P.; Forster, T.M.; Singh, A.; Coste, A.T.; Andes, D.R.; Hube, B.; Sanglard, D.; Chauhan, N.; Kaur, R.; et al. Pleiotropic effects of the vacuolar ABC transporter MLT1 of Candida albicans on cell function and virulence. Biochem. J. 2016, 473, 1537–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ha, K.C.; White, T.C. Effects of azole antifungal drugs on the transition from yeast cells to hyphae in susceptible and resistant isolates of the pathogenic yeast Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1999, 43, 763–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, Y.Q.; Rao, R. Beyond ergosterol: Linking pH to antifungal mechanisms. Virulence 2010, 1, 551–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaylord, E.A.; Choy, H.L.; Doering, T.L. Dangerous Liaisons: Interactions of Cryptococcus neoformans with Host Phagocytes. Pathogens 2020, 9, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gaylord, E.A.; Choy, H.L.; Chen, G.; Briner, S.L.; Doering, T.L. Sac1 links phosphoinositide turnover to cryptococcal virulence. MBio 2024, 15, e0149624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chang, C.C.; Harrison, T.S.; Bicanic, T.A.; Chayakulkeeree, M.; Sorrell, T.C.; Warris, A.; Hagen, F.; Spec, A.; Oladele, R.; Govender, N.P.; et al. Global guideline for the diagnosis and management of cryptococcosis: An initiative of the ECMM and ISHAM in cooperation with the ASM. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, e495–e512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothe, C.; Sloan, D.J.; Goodson, P.; Chikafa, J.; Mukaka, M.; Denis, B.; Harrison, T.; van Oosterhout, J.J.; Heyderman, R.S.; Lalloo, D.G.; et al. A prospective longitudinal study of the clinical outcomes from cryptococcal meningitis following treatment induction with 800 mg oral fluconazole in Blantyre, Malawi. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e67311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li, S.C.; Kane, P.M. The yeast lysosome-like vacuole: Endpoint and crossroads. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2009, 1793, 650–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Steinberg, G.; Schliwa, M.; Lehmler, C.; Bolker, M.; Kahmann, R.; McIntosh, J.R. Kinesin from the plant pathogenic fungus Ustilago maydis is involved in vacuole formation and cytoplasmic migration. J. Cell Sci. 1998, 111 Pt 15, 2235–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Song, M.; Do, E.; Choi, Y.; Kronstad, J.W.; Jung, W.H. Oxidative Stress Causes Vacuolar Fragmentation in the Human Fungal Pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Urbanowski, J.L.; Piper, R.C. The iron transporter Fth1p forms a complex with the Fet5 iron oxidase and resides on the vacuolar membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 38061–38070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khandelwal, N.K.; Wasi, M.; Nair, R.; Gupta, M.; Kumar, M.; Mondal, A.K.; Gaur, N.A.; Prasad, R. Vacuolar Sequestration of Azoles, a Novel Strategy of Azole Antifungal Resistance Conserved across Pathogenic and Nonpathogenic Yeast. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e01347-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jin, Y.; Weisman, L.S. The vacuole/lysosome is required for cell-cycle progression. eLife 2015, 4, e08160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Altamirano, S.; Li, Z.; Fu, M.S.; Ding, M.; Fulton, S.R.; Yoder, J.M.; Tran, V.; Nielsen, K. The Cyclin Cln1 Controls Polyploid Titan Cell Formation following a Stress-Induced G(2) Arrest in Cryptococcus. MBio 2021, 12, e0250921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, R.; Liu, J.; Fan, M.; Ye, Z.; Hao, Y.; Xie, F.; Wang, T.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, N.; et al. The vacuolar fusion regulated by HOPS complex promotes hyphal initiation and penetration in Candida albicans. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stuckey, P.V.; Marine, J.; Figueras, M.; Collins, A.; Santiago-Tirado, F.H. The Vacuolar Protein 8 (Vac8) Homolog in Cryptococcus neoformans Impacts Stress Responses and Virulence Traits Through Conserved and Unique Roles. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 877. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120877

Stuckey PV, Marine J, Figueras M, Collins A, Santiago-Tirado FH. The Vacuolar Protein 8 (Vac8) Homolog in Cryptococcus neoformans Impacts Stress Responses and Virulence Traits Through Conserved and Unique Roles. Journal of Fungi. 2025; 11(12):877. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120877

Chicago/Turabian StyleStuckey, Peter V., Julia Marine, Meghan Figueras, Aliyah Collins, and Felipe H. Santiago-Tirado. 2025. "The Vacuolar Protein 8 (Vac8) Homolog in Cryptococcus neoformans Impacts Stress Responses and Virulence Traits Through Conserved and Unique Roles" Journal of Fungi 11, no. 12: 877. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120877

APA StyleStuckey, P. V., Marine, J., Figueras, M., Collins, A., & Santiago-Tirado, F. H. (2025). The Vacuolar Protein 8 (Vac8) Homolog in Cryptococcus neoformans Impacts Stress Responses and Virulence Traits Through Conserved and Unique Roles. Journal of Fungi, 11(12), 877. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120877