Wheat DNA Methyltransferase TaMET1 Negatively Regulates Salicylic Acid Biosynthesis to Facilitate Powdery Mildew Susceptibility

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant and Fungal Materials Maintenance

2.2. Gene Transcription Rate and Expression Level Measurement

2.3. Gene Silencing Assay

2.4. Gene Overexpression Assay

2.5. Wheat-Powdery Mildew Interaction Analysis

2.6. SA Content Analysis

2.7. DNA Methylation Analysis

2.8. Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assay and Nucleosomal Occupancy Analysis

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

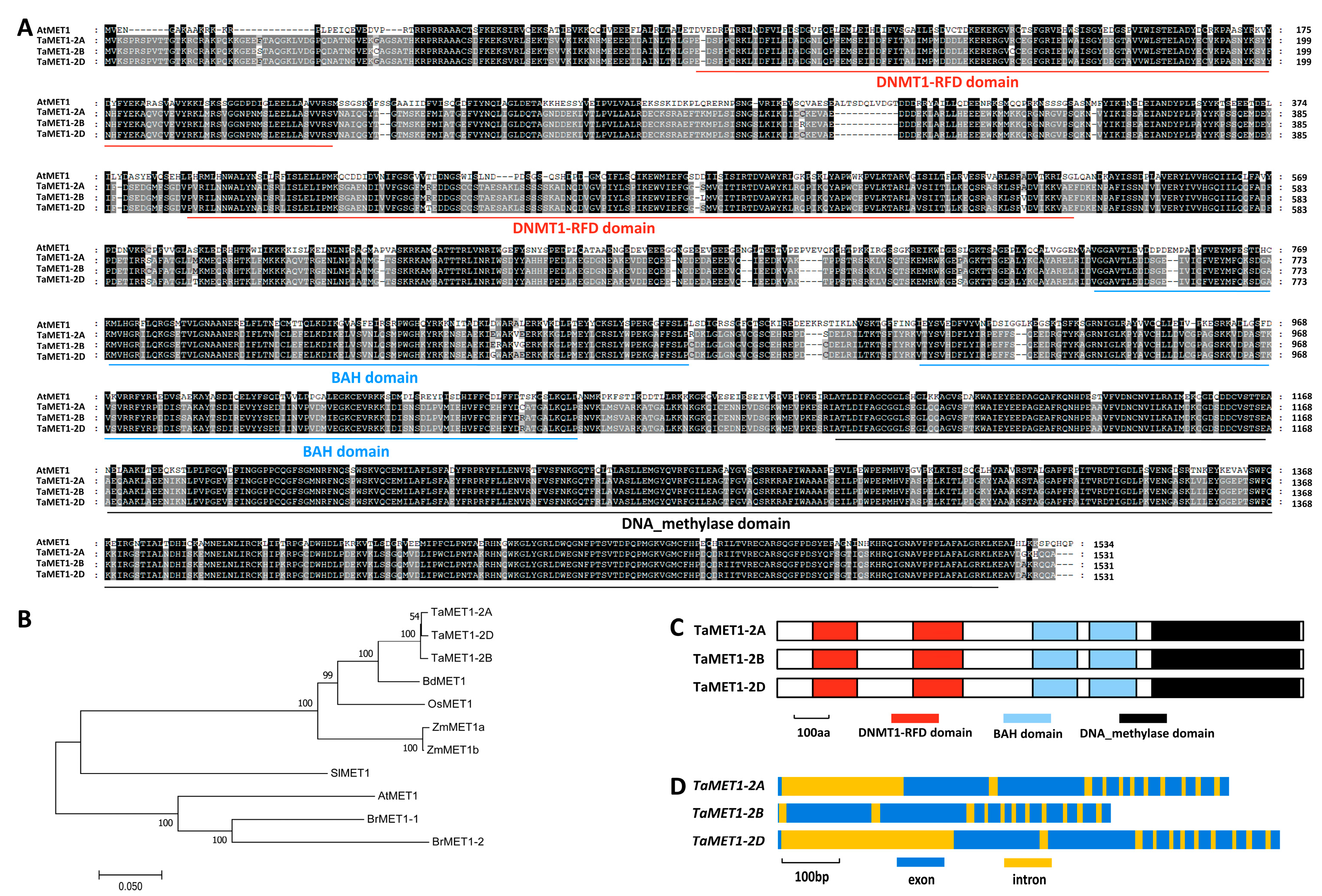

3.1. Homology-Based Identification of Wheat TaMET1 Genes

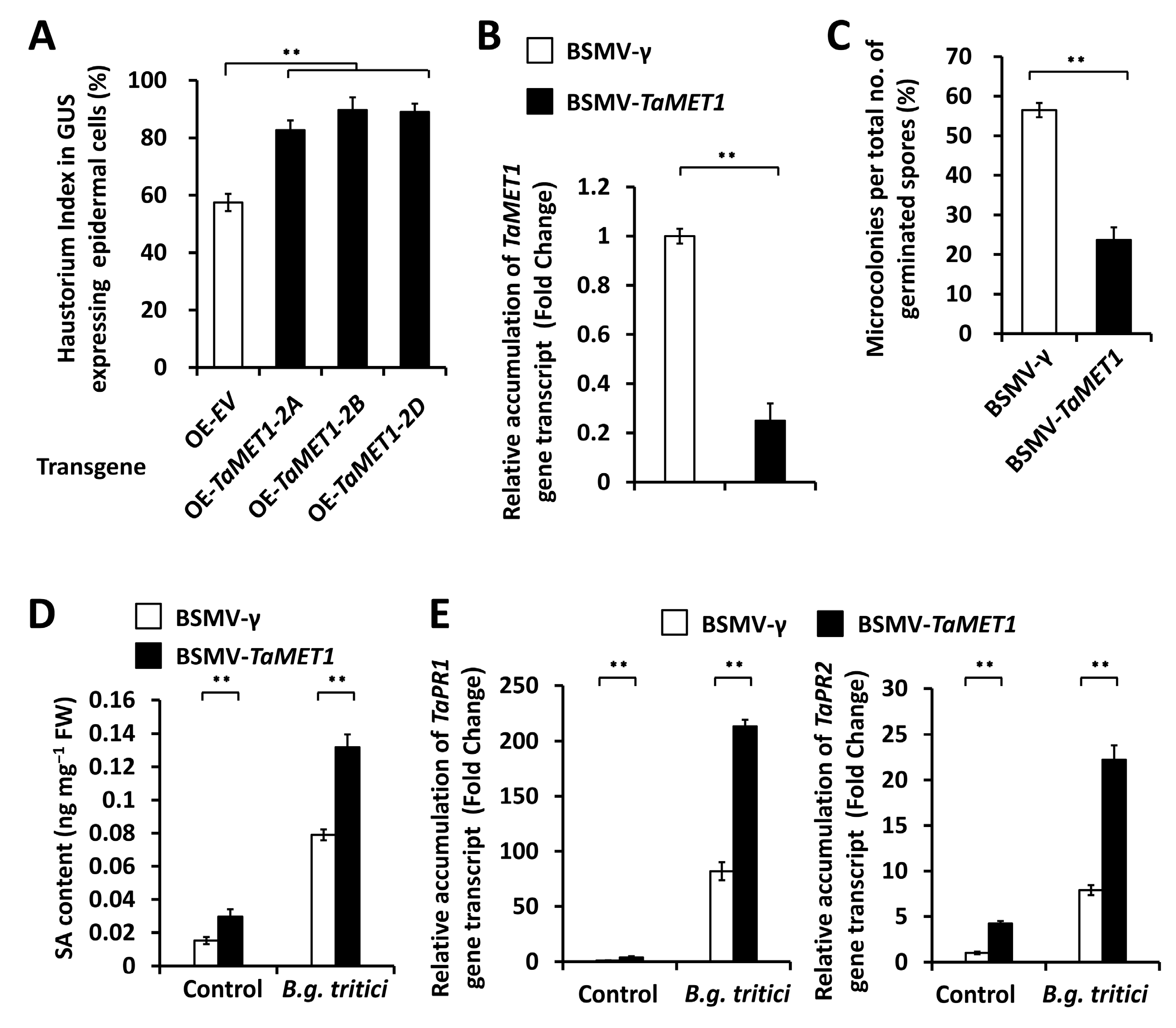

3.2. Functional Analysis of TaMET1 Genes in the Regulation of Wheat Susceptibility to B.g. tritici

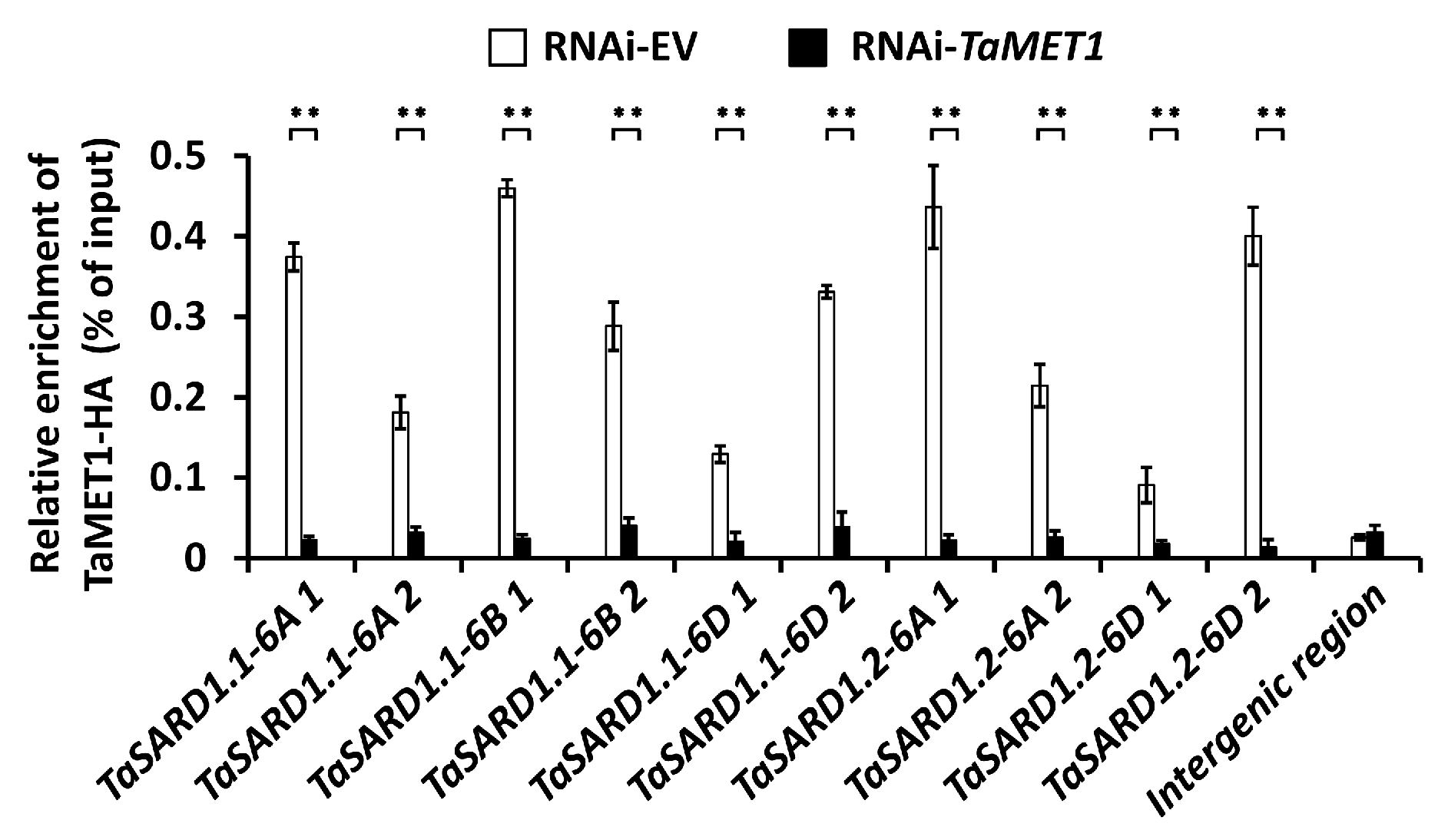

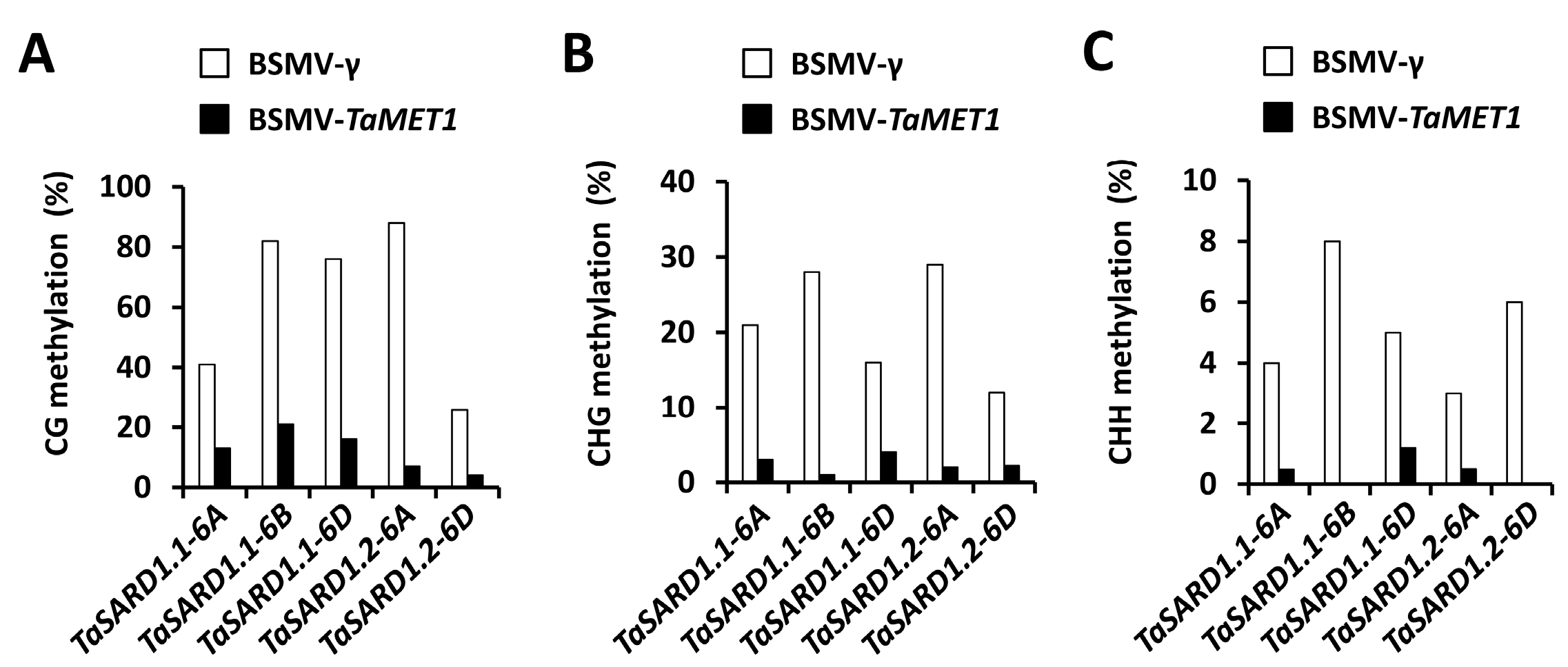

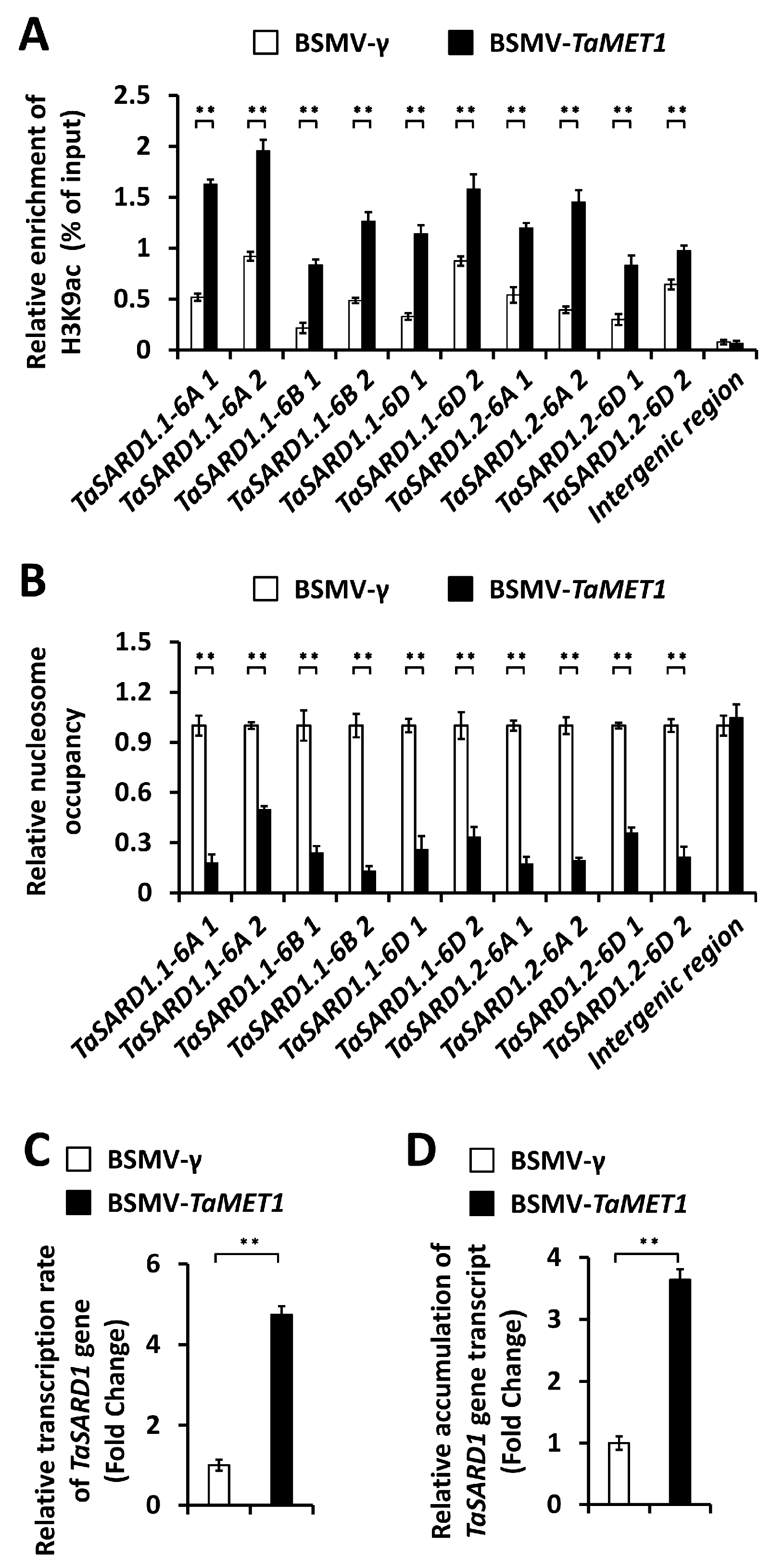

3.3. Epigenetic Regulation of SA Biosynthesis Activator Gene TaSARD1 by TaMET1

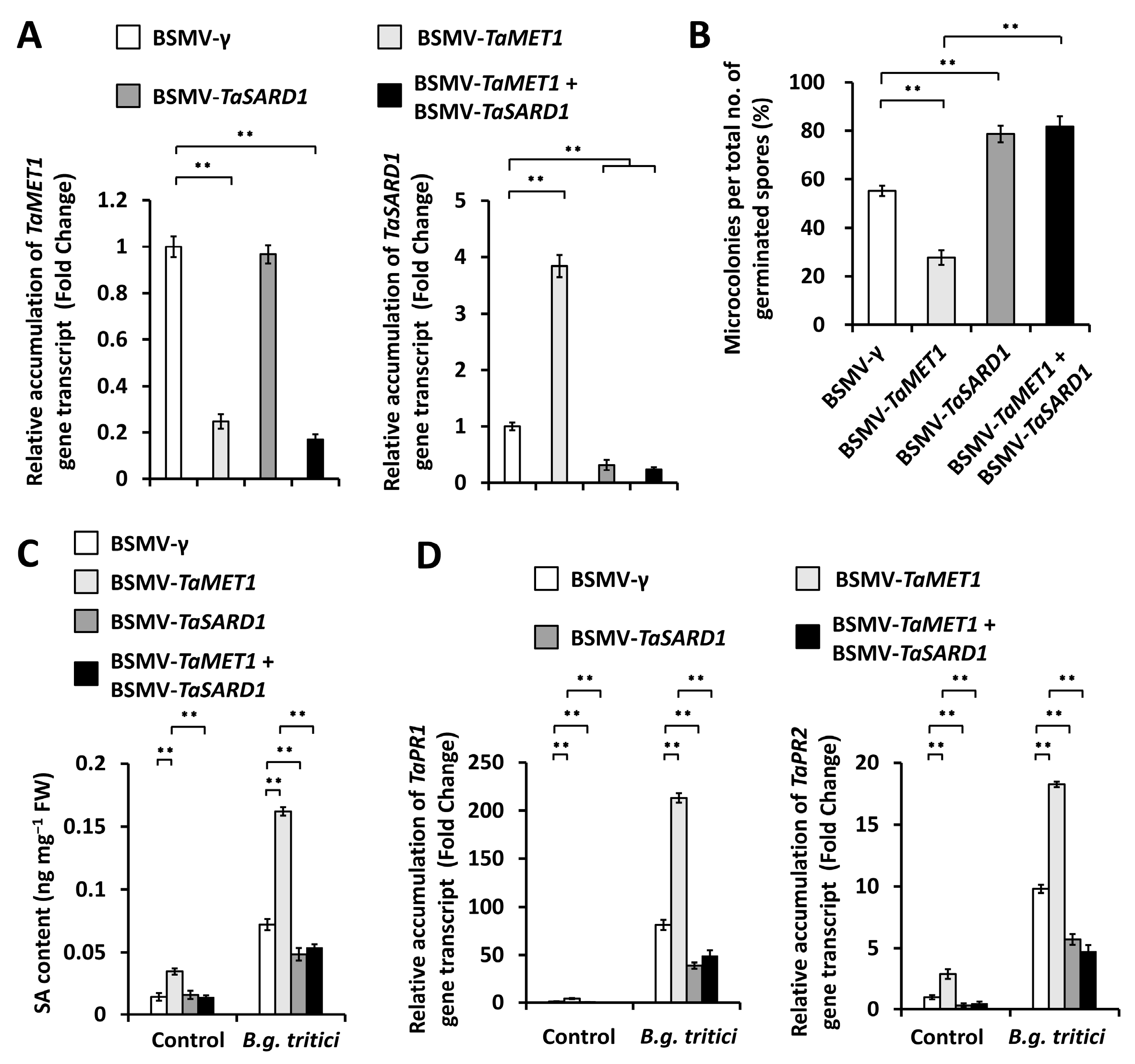

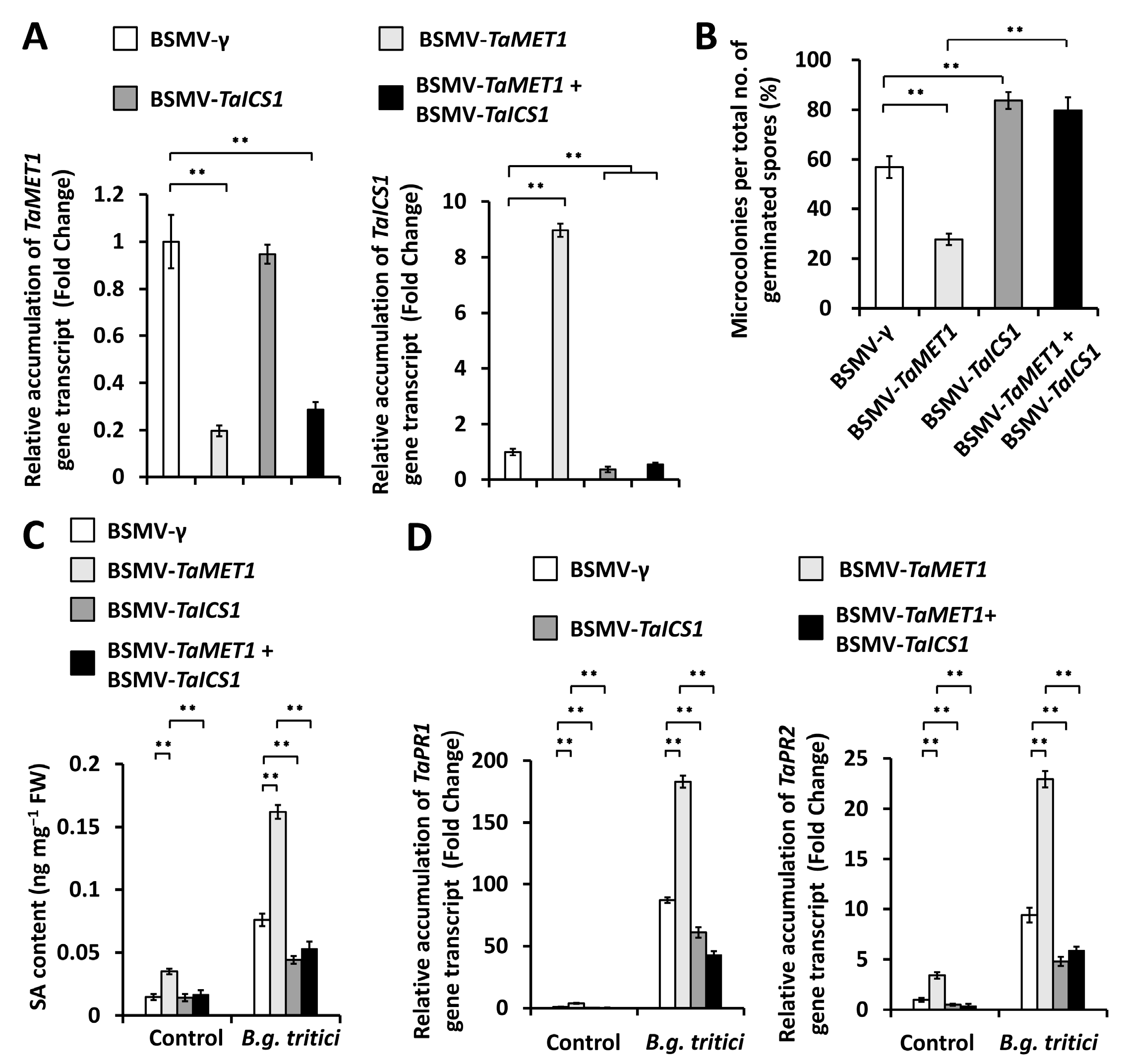

3.4. Functional Analysis of TaSARD1-TaICS1-SA Circuit in the TaMET1-Governed Wheat Powdery Mildew Susceptibility

4. Discussion

4.1. The DNA Methyltransferase TaMET1 Facilitates the Wheat Powdery Mildew Susceptibility

4.2. The DNA Methyltransferase TaMET1 Epigenetically Suppresses SA Biosynthesis

4.3. Potentials of Exploiting Susceptibility Gene TaMET1 in Wheat Breeding Against Powdery Mildew Disease

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Levy, A.A.; Feldman, M. Evolution and origin of bread wheat. Plant Cell 2022, 34, 2549–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R. The outlook for population growth. Science 2011, 333, 569–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savary, S.; Willocquet, L.; Pethybridge, S.J.; Esker, P.; McRoberts, N.; Nelson, A. The global burden of pathogens and pests on major food crops. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 3, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusch, S.; Qian, J.; Loos, A.; Kümmel, F.; Spanu, P.D.; Panstruga, R. Long-term and rapid evolution in powdery mildew fungi. Mol. Ecol. 33, e16909. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mapuranga, J.; Chang, J.; Yang, W. Combating powdery mildew: Advances in molecular interactions between Blumeria graminis f.sp. tritici and wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1102908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, I.R.; Jacobsen, S.E. Epigenetic inheritance in plants. Nature 2007, 447, 418–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srikant, T.; Yuan, W.; Berendzen, K.W.; Contreras-Garrido, A.; Drost, H.G.; Schwab, R.; Weigel, D. Canalization of genome-wide transcriptional activity in Arabidopsis thaliana accessions by MET1-dependent CG methylation. Genome Biol. 2022, 23, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yu, C.W.; Duan, J.; Luo, M.; Wang, K.; Tian, G.; Cui, Y.; Wu, K. HDA6 directly interacts with DNA methyltransferase MET1 and maintains transposable element silencing in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2012, 158, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A.; Wöhrmann, H.J.; Raissig, M.T.; Arand, J.; Gheyselinck, J.; Gagliardini, V.; Heichinger, C.; Walter, J.; Grossniklaus, U. The Polycomb group protein MEDEA and the DNA methyltransferase MET1 interact to repress autonomous endosperm development in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2013, 73, 776–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, S.; Lee, H.G.; Seo, P.J. MET1-Dependent DNA Methylation Represses Light Signaling and Influences Plant Regeneration in Arabidopsis. Mol. Cells 2021, 44, 746–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yang, Z.; Wang, X.; Chen, W.; Fu, Y.; Zhi, P.; Chang, C. Wheat chromatin assembly factor-1 negatively regulates the biosynthesis of cuticular wax and salicylic acid to fine-tune powdery mildew susceptibility. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 21786–21802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.; Li, C.; Yan, L.; Jackson, A.O.; Liu, Z.; Han, C.; Yu, J.; Li, D. A high throughput barley stripe mosaic virus vector for virus induced gene silencing in monocots and dicots. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e26468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Li, H.; Zhi, P.; Chang, C. Wheat chromatin remodeling protein TaSWP73 contributes to compatible wheat-powdery mildew interaction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, H.; Xu, L.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y. Salicylic acid: The roles in plant immunity and crosstalk with other hormones. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2025, 67, 773–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Z.; Man, J.; Xu, D.; Wen, L.; Li, Y.H.; Deng, M.; Jiang, Q.T.; Xu, Q.; Chen, G.Y.; Wei, Y.M. Investigating the mechanisms of isochorismate synthase: An approach to improve salicylic acid synthesis and increase resistance to Fusarium head blight in wheat. Crop J. 2024, 12, 1054–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhi, P.; Wang, X.; Fan, Q.; Chang, C. Wheat WD40-repeat protein TaHOS15 functions in a histone deacetylase complex to fine-tune defense responses to Blumeria graminis f.sp. tritici. J. Exp. Bot. 2019, 70, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, N.; Lin, J.; Liu, X.; Liu, Z.; Liu, D.; Chu, W.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Chang, S.; Yang, Q.; et al. Histone acetyltransferase TaHAG1 interacts with TaPLATZ5 to activate TaPAD4 expression and positively contributes to powdery mildew resistance in wheat. New Phytol. 2022, 236, 590–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Zhao, J.; Duan, W.; Tian, S.; Wang, X.; Zhuang, H.; Fu, J.; Kang, Z. TaAMT2;3a, a wheat AMT2-type ammonium transporter, facilitates the infection of stripe rust fungus on wheat. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.W.; Herrera-Foessel, S.; Lan, C.; Schnippenkoetter, W.; Ayliffe, M.; Huerta-Espino, J.; Lillemo, M.; Viccars, L.; Milne, R.; Periyannan, S.; et al. A recently evolved hexose transporter variant confers resistance to multiple pathogens in wheat. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 1494–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huai, B.; Yang, Q.; Qian, Y.; Qian, W.; Kang, Z.; Liu, J. ABA-induced sugar transporter TaSTP6 promotes wheat susceptibility to stripe rust. Plant Physiol. 2019, 181, 1328–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huai, B.; Yang, Q.; Wei, X.; Pan, Q.; Kang, Z.; Liu, J. TaSTP13 contributes to wheat susceptibility to stripe rust possibly by increasing cytoplasmic hexose concentration. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huai, B.; Yuan, P.; Ma, X.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, L.; Zheng, P.; Yao, M.; Chen, Z.; Chen, L.; Shen, Q.; et al. Sugar transporter TaSTP3 activation by TaWRKY19/61/82 enhances stripe rust susceptibility in wheat. New Phytol. 2022, 236, 266–282. [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi, S.S.; Mukhtar, M.S.; Mansoor, S. Editing: Targeting susceptibility genes for plant disease resistance. Trends Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 898–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Schie, C.C.; Takken, F.L. Susceptibility genes 101: How to be a good host. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2014, 52, 551–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koseoglou, E.; van der Wolf, J.M.; Visser, R.; Bai, Y. Susceptibility reversed: Modified plant susceptibility genes for resistance to bacteria. Trends Plant Sci. 2022, 27, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Lin, D.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, M.; Chen, Y.; Lv, B.; Li, B.; Lei, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, L.; et al. Genome-edited powdery mildew resistance in wheat without growth penalties. Nature 2022, 602, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Bai, Y.; Wu, G.; Zou, S.; Chen, Y.; Gao, C.; Tang, D. Simultaneous modification of three homoeologs of TaEDR1 by genome editing enhances powdery mildew resistance in wheat. Plant J. 2017, 91, 714–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCallum, C.M.; Comai, L.; Greene, E.A.; Henikoff, S. Targeting induced local lesions IN genomes (TILLING) for plant functional genomics. Plant Physiol. 2000, 123, 439–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurowska, M.; Daszkowska-Golec, A.; Gruszka, D.; Marzec, M.; Szurman, M.; Szarejko, I.; Maluszynski, M. TILLING: A shortcut in functional genomics. J. Appl. Genet. 2011, 52, 371–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Hao, L.; Parry, M.A.; Phillips, A.L.; Hu, Y.G. Progress in TILLING as a tool for functional genomics and improvement of crops. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2014, 56, 425–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, K.; Qiu, J.L. Genome editing for plant disease resistance: Applications and perspectives. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2019, 374, 20180322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Li, C.; Gao, C. Applications of CRISPR-Cas in agriculture and plant biotechnology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 661–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenke, D.; Cai, D. Applications of CRISPR/Cas to improve crop disease resistance: Beyond inactivation of susceptibility factors. iScience 2020, 23, 101478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Cheng, X.; Shan, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Gao, C.; Qiu, J.L. Simultaneous editing of three homoeoalleles in hexaploid bread wheat confers heritable resistance to powdery mildew. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 947–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ge, P.; Chen, W.; Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Chang, C. Wheat DNA Methyltransferase TaMET1 Negatively Regulates Salicylic Acid Biosynthesis to Facilitate Powdery Mildew Susceptibility. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 876. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120876

Ge P, Chen W, Liu J, Wang X, Chang C. Wheat DNA Methyltransferase TaMET1 Negatively Regulates Salicylic Acid Biosynthesis to Facilitate Powdery Mildew Susceptibility. Journal of Fungi. 2025; 11(12):876. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120876

Chicago/Turabian StyleGe, Pengkun, Wanzhen Chen, Jiao Liu, Xiaoyu Wang, and Cheng Chang. 2025. "Wheat DNA Methyltransferase TaMET1 Negatively Regulates Salicylic Acid Biosynthesis to Facilitate Powdery Mildew Susceptibility" Journal of Fungi 11, no. 12: 876. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120876

APA StyleGe, P., Chen, W., Liu, J., Wang, X., & Chang, C. (2025). Wheat DNA Methyltransferase TaMET1 Negatively Regulates Salicylic Acid Biosynthesis to Facilitate Powdery Mildew Susceptibility. Journal of Fungi, 11(12), 876. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120876