The Zinc Finger Protein Zfp2 Regulates Cell–Cell Fusion and Virulence in Cryptococcus neoformans

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strains and Growth Conditions

2.2. RT-qPCR

2.3. Generation of GFP-Tagged Strains

2.4. FM4-64 and DAPI Staining

2.5. Generation of ZFP2 Deletion, Complementation, and Overexpression Strains

2.6. Virulence Factor Production Assay and Growth Under Stress Conditions

2.7. Fungal Mating Assays

2.8. Cell–Cell Fusion Assay

2.9. Virulence Studies

2.10. Fungal Burdens and Histopathological Examination in Infected Organs

2.11. Serum Treatment and Cryptococcus–Macrophage Interaction Assay

3. Results

3.1. Identification of Zinc Finger Protein Zfp2

3.2. Zfp2 Is Involved in Capsule Formation and Cell Wall/Membrane Integrity in C. neoformans

3.3. Zfp2 Plays a Role in the Cell–Cell Fusion Process During the Sexual Reproduction of C. neoformans

3.4. Zfp2 Regulates Key Genes in the Pheromone-Sensing Pathway of C. neoformans

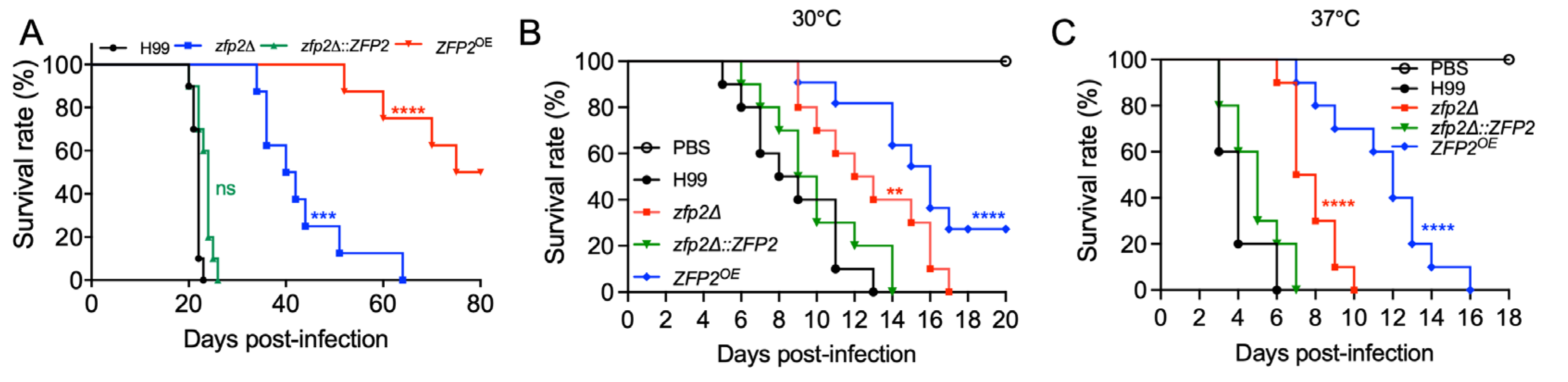

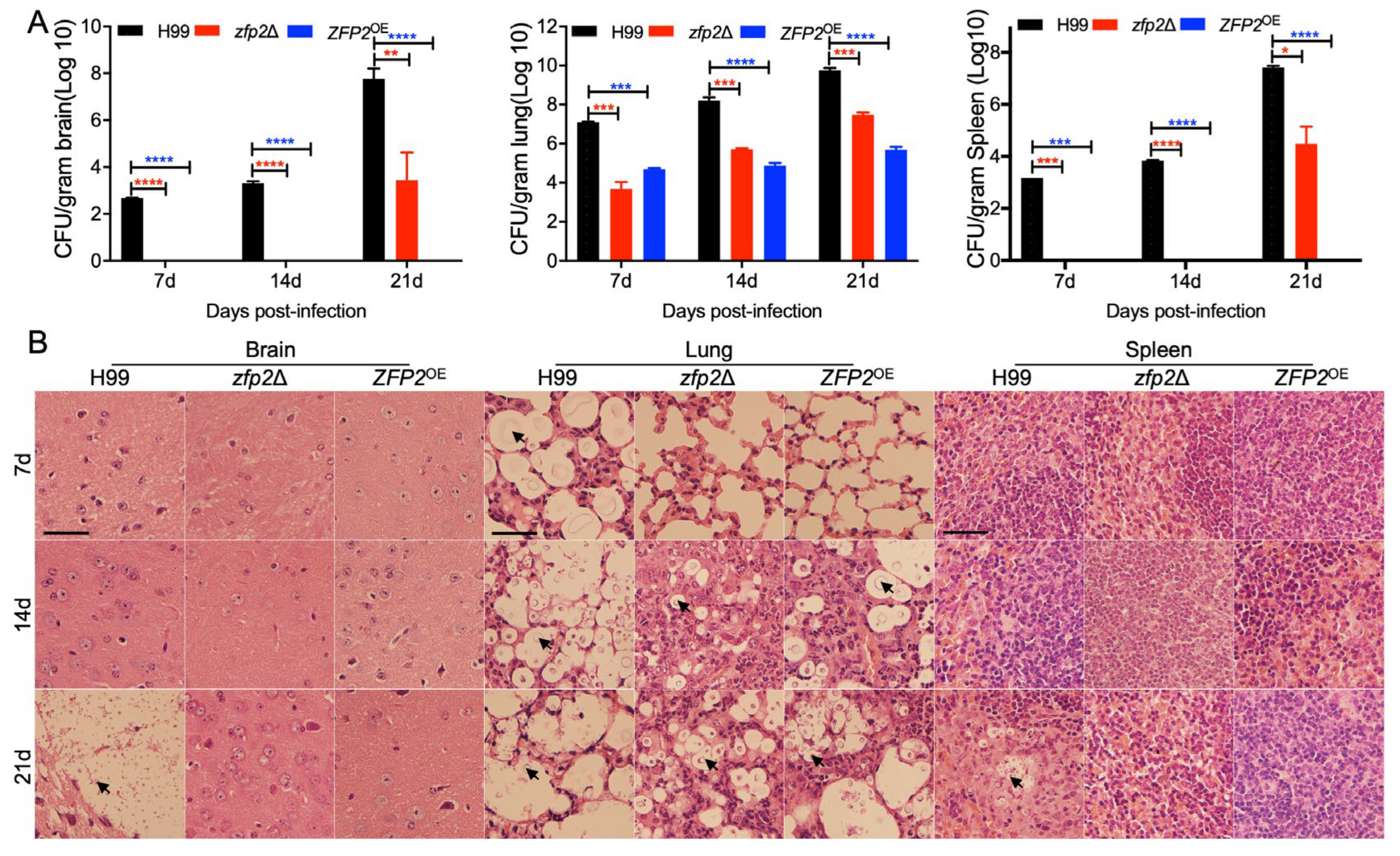

3.5. Zfp2 Plays an Important Role in Fungal Virulence in Mouse and Wax Moth Infection Models

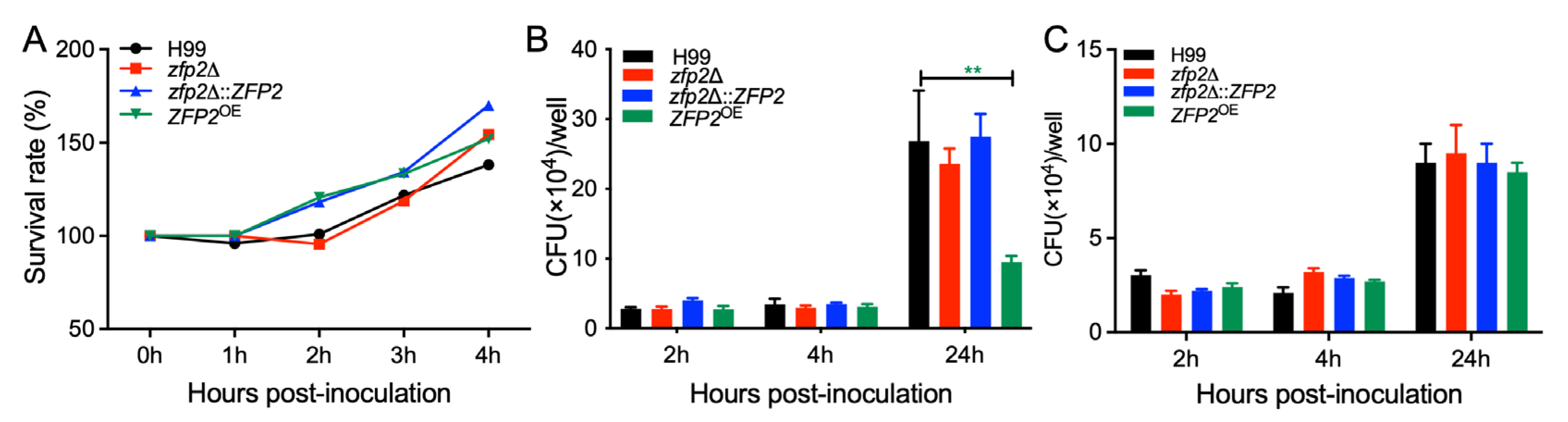

3.6. Zfp2 Is Involved in the Proliferation of C. neoformans in Macrophage Cells

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Casadevall, A.; Perfect, J.R. Cryptococcus Neoformans; ASM Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Park, B.J.; Wannemuehler, K.A.; Marston, B.J.; Govender, N.; Pappas, P.G.; Chiller, T.M. Estimation of the current global burden of cryptococcal meningitis among persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS 2009, 23, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajasingham, R.; Govender, N.P.; Jordan, A.; Loyse, A.; Shroufi, A.; Denning, D.W.; Meya, D.B.; Chiller, T.M.; Boulware, D.R. The global burden of HIV-associated cryptococcal infection in adults in 2020: A modelling analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 1748–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajasingham, R.; Smith, R.M.; Park, B.J.; Jarvis, J.N.; Govender, N.P.; Chiller, T.M.; Denning, D.W.; Loyse, A.; Boulware, D.R. Global burden of disease of HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis: An updated analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 873–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denning, D.W. Global incidence and mortality of severe fungal disease. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, e428–e438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoneda, A.; Doering, T.L. A eukaryotic capsular polysaccharide is synthesized intracellularly and secreted via exocytosis. Mol. Biol. Cell 2006, 17, 5131–5140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, D.L.; Freire-de-Lima, C.G.; Nosanchuk, J.D.; Casadevall, A.; Rodrigues, M.L.; Nimrichter, L. Extracellular vesicles from Cryptococcus neoformans modulate macrophage functions. Infect. Immun. 2010, 78, 1601–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frases, S.; Salazar, A.; Dadachova, E.; Casadevall, A. Cryptococcus neoformans can utilize the bacterial melanin precursor homogentisic acid for fungal melanogenesis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 615–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, F.J.; Idnurm, A.; Heitman, J. Novel gene functions required for melanization of the human pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol. Microbiol. 2005, 57, 1381–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettit, R.K.; Repp, K.K.; Hazen, K.C. Temperature affects the susceptibility of Cryptococcus neoformans biofilms to antifungal agents. Med. Mycol. 2010, 48, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, C.M.; Heitman, J. Genetics of Cryptococcus neoformans. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2002, 36, 557–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengeler, K.B.; Fox, D.S.; Fraser, J.A.; Allen, A.; Forrester, K.; Dietrich, F.S.; Heitman, J. Mating-type locus of Cryptococcus neoformans: A step in the evolution of sex chromosomes. Eukaryot. Cell 2002, 1, 704–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, X.; Nielsen, K.; Patel, S.; Heitman, J. Impact of mating type, serotype, and ploidy on the virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect. Immun. 2008, 76, 2923–2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, X.; Heitman, J. The biology of the Cryptococcus neoformans species complex. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2006, 60, 69–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Lin, X. Mechanisms of unisexual mating in Cryptococcus neoformans. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2011, 48, 651–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Fu, C.; Ianiri, G.; Heitman, J. The Pheromone and Pheromone Receptor Mating-Type Locus Is Involved in Controlling Uniparental Mitochondrial Inheritance in Cryptococcus. Genetics 2020, 214, 703–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Huang, J.C.; Mitchell, T.G.; Heitman, J. Virulence attributes and hyphal growth of C. neoformans are quantitative traits and the MATalpha allele enhances filamentation. PLoS Genet. 2006, 2, e187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, T.; Lin, X.; Malik, R.; Heitman, J.; Carter, D. Isolates of Cryptococcus neoformans from infected animals reveal genetic exchange in unisexual, alpha mating type populations. Eukaryot. Cell 2008, 7, 1771–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.; Mclachlan, A.D.; Klug, A. Repetitive Zinc-Binding Domains in the Protein Transcription Factor Iiia from Xenopus oocytes. EMBO J. 1985, 4, 1609–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, A.; Vij, S.; Tyagi, A.K. Overexpression of a zinc-finger protein gene from rice confers tolerance to cold, dehydration, and salt stress in transgenic tobacco. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 6309–6314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Choi, K.; Park, C.; Hwang, H.J.; Lee, I. SUPPRESSOR OF FRIGIDA4, encoding a C2H2-Type zinc finger protein, represses flowering by transcriptional activation of Arabidopsis FLOWERING LOCUS C. Plant Cell 2006, 18, 2985–2998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Huang, P.; Zhang, L.; Shi, Y.; Sun, D.; Yan, Y.; Liu, X.; Dong, B.; Chen, G.; Snyder, J.H.; et al. Characterization of 47 Cys2 -His2 zinc finger proteins required for the development and pathogenicity of the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. New Phytol. 2016, 211, 1035–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirayama, S.; Sugiura, R.; Lu, Y.; Maeda, T.; Kawagishi, K.; Yokoyama, M.; Tohda, H.; Giga-Hama, Y.; Shuntoh, H.; Kuno, T. Zinc finger protein Prz1 regulates Ca2+ but not Cl- homeostasis in fission yeast. Identification of distinct branches of calcineurin signaling pathway in fission yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 18078–18084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Li, G.; Lin, C.; He, C. Conidiophore stalk-less1 encodes a putative zinc-finger protein involved in the early stage of conidiation and mycelial infection in Magnaporthe oryzae. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2009, 22, 402–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matheis, S.; Yemelin, A.; Scheps, D.; Andresen, K.; Jacob, S.; Thines, E.; Foster, A.J. Functions of the Magnaporthe oryzae Flb3p and Flb4p transcription factors in the regulation of conidiation. Microbiol. Res. 2017, 196, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Wang, Z.L.; Zhang, L.B.; Ying, S.H.; Feng, M.G. The role of three calcineurin subunits and a related transcription factor (Crz1) in conidiation, multistress tolerance and virulence in Beauveria bassiana. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 827–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Pastor, M.T.; Marchler, G.; Schuller, C.; Marchler-Bauer, A.; Ruis, H.; Estruch, F. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae zinc finger proteins Msn2p and Msn4p are required for transcriptional induction through the stress response element (STRE). EMBO J. 1996, 15, 2227–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Ward, M.P.; Garrett, S. Yeast PKA represses Msn2p/Msn4p-dependent gene expression to regulate growth, stress response and glycogen accumulation. EMBO J. 1998, 17, 3556–3564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, D.G.; Huh, W.K. PKA, PHO and stress response pathways regulate the expression of UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase through Msn2/4 in budding yeast. FEBS Lett. 2015, 589, 2409–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoli, M.T.; Espeso, E.A. Modulation of calcineurin activity in Aspergillus nidulans: The roles of high magnesium concentrations and of transcriptional factor CrzA. Mol. Microbiol. 2019, 111, 1283–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.S.; Yu, Y.M.; Kim, Y.J.; Maeng, P.J. Negative regulation of the vacuole-mediated resistance to K(+) stress by a novel C2H2 zinc finger transcription factor encoded by aslA in Aspergillus nidulans. J. Microbiol. 2015, 53, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Jackson, J.C.; Feretzaki, M.; Xue, C.; Heitman, J. Transcription factors Mat2 and Znf2 operate cellular circuits orchestrating opposite- and same-sex mating in Cryptococcus neoformans. PLoS Genet. 2010, 6, e1000953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feretzaki, M.; Heitman, J. Genetic Circuits that Govern Bisexual and Unisexual Reproduction in Cryptococcus neoformans. PLos Genet. 2013, 9, e1003688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, C.L.; Han, L.T.; Jiang, S.T.; Chang, A.N.; Zhou, Z.Y.; Liu, T.B. The Cys2His2 zinc finger protein Zfp1 regulates sexual reproduction and virulence in Cryptococcus neoformans. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2019, 124, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perfect, J.R.; Ketabchi, N.; Cox, G.M.; Ingram, C.W.; Beiser, C.L. Karyotyping of Cryptococcus neoformans as an epidemiological tool. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1993, 31, 3305–3309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, K.; Cox, G.M.; Wang, P.; Toffaletti, D.L.; Perfect, J.R.; Heitman, J. Sexual cycle of Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii and virulence of congenic a and alpha isolates. Infect. Immun. 2003, 71, 4831–4841. [Google Scholar]

- Bahn, Y.S.; Hicks, J.K.; Giles, S.S.; Cox, G.M.; Heitman, J. Adenylyl cyclase-associated protein Aca1 regulates virulence and differentiation of Cryptococcus neoformans via the cyclic AMP-protein kinase A cascade. Eukaryot. Cell 2004, 3, 1476–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, M.S.; Nichols, C.B.; Alspaugh, J.A. The Cryptococcus neoformans Rho-GDP dissociation inhibitor mediates intracellular survival and virulence. Infect. Immun. 2008, 76, 5729–5737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.B.; Wang, Y.; Stukes, S.; Chen, Q.; Casadevall, A.; Xue, C. The F-Box protein Fbp1 regulates sexual reproduction and virulence in Cryptococcus neoformans. Eukaryot. Cell 2011, 10, 791–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaragoza, O.; Casadevall, A. Experimental modulation of capsule size in Cryptococcus neoformans. Biol. Proced. Online 2004, 6, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Q.H.; Han, L.T.; Guo, M.R.; Fan, C.L.; Liu, T.B. Role of the Anaphase-Promoting Complex Activator Cdh1 in the Virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, J.A.; Subaran, R.L.; Nichols, C.B.; Heitman, J. Recapitulation of the sexual cycle of the primary fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii: Implications for an outbreak on Vancouver Island, Canada. Eukaryot. Cell 2003, 2, 1036–1045. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, C.; Bahn, Y.S.; Cox, G.M.; Heitman, J. G protein-coupled receptor Gpr4 senses amino acids and activates the cAMP-PKA pathway in Cryptococcus neoformans. Mol. Biol. Cell 2006, 17, 667–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aminnejad, M.; Cogliati, M.; Duan, S.; Arabatzis, M.; Tintelnot, K.; Castaneda, E.; Lazera, M.; Velegraki, A.; Ellis, D.; Sorrell, T.C.; et al. Identification and Characterization of VNI/VNII and Novel VNII/VNIV Hybrids and Impact of Hybridization on Virulence and Antifungal Susceptibility Within the C. neoformans/C. gattii Species Complex. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0163955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, W.C.; Davidson, R.C.; Cox, G.M.; Heitman, J. Pheromones stimulate mating and differentiation via paracrine and autocrine signaling in Cryptococcus neoformans. Eukaryot. Cell 2002, 1, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, S.; Karos, M.; Chang, Y.C.; Lukszo, J.; Wickes, B.L.; Kwon-Chung, K.J. Molecular analysis of CPRalpha, a MATalpha-specific pheromone receptor gene of Cryptococcus neoformans. Eukaryot. Cell 2002, 1, 432–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsueh, Y.P.; Shen, W.C. A homolog of Ste6, the a-factor transporter in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, is required for mating but not for monokaryotic fruiting in Cryptococcus neoformans. Eukaryot. Cell 2005, 4, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crook, N.E.; Clem, R.J.; Miller, L.K. An apoptosis-inhibiting baculovirus gene with a zinc finger-like motif. J. Virol. 1993, 67, 2168–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, K.; Zhou, X.; Kunkel, G.; Zhang, Z.; Deng, J.M.; Behringer, R.R.; de Crombrugghe, B. The novel zinc finger-containing transcription factor osterix is required for osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Cell 2002, 108, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.C. Arginine-rich motif-tandem CCCH zinc finger proteins in plant stress responses and post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression. Plant Sci. 2016, 252, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imbeault, M.; Helleboid, P.Y.; Trono, D. KRAB zinc-finger proteins contribute to the evolution of gene regulatory networks. Nature 2017, 543, 550–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaragoza, O.; Rodrigues, M.L.; De Jesus, M.; Frases, S.; Dadachova, E.; Casadevall, A. The capsule of the fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 2009, 68, 133–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.D.; Williamson, P.R. Masking the Pathogen: Evolutionary Strategies of Fungi and Their Bacterial Counterparts. J. Fungi 2015, 1, 397–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moyrand, F.; Fontaine, T.; Janbon, G. Systematic capsule gene disruption reveals the central role of galactose metabolism on Cryptococcus neoformans virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 2007, 64, 771–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, K.E.; Fraser, J.A.; Carter, D.A. Lineages Derived from Cryptococcus neoformans Type Strain H99 Support a Link between the Capacity to Be Pleomorphic and Virulence. mBio 2022, 13, e0028322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, W.H.; Son, Y.E.; Oh, S.H.; Fu, C.; Kim, H.S.; Kwak, J.H.; Cardenas, M.E.; Heitman, J.; Park, H.S. Had1 Is Required for Cell Wall Integrity and Fungal Virulence in Cryptococcus neoformans. G3 (Bethesda) 2018, 8, 643–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, A.; Park, Y.D.; Larsen, P.; Nagarajan, V.; Wollenberg, K.; Qiu, J.; Myers, T.G.; Williamson, P.R. A novel specificity protein 1 (SP1)-like gene regulating protein kinase C-1 (Pkc1)-dependent cell wall integrity and virulence factors in Cryptococcus neoformans. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 20977–20990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lev, S.; Desmarini, D.; Chayakulkeeree, M.; Sorrell, T.C.; Djordjevic, J.T. The Crz1/Sp1 transcription factor of Cryptococcus neoformans is activated by calcineurin and regulates cell wall integrity. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e51403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhai, B.; Lin, X. The link between morphotype transition and virulence in Cryptococcus neoformans. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, B.; Zhu, P.; Foyle, D.; Upadhyay, S.; Idnurm, A.; Lin, X. Congenic strains of the filamentous form of Cryptococcus neoformans for studies of fungal morphogenesis and virulence. Infect. Immun. 2013, 81, 2626–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Idnurm, A.; Lin, X. Morphology and its underlying genetic regulation impact the interaction between Cryptococcus neoformans and its hosts. Med. Mycol. 2015, 53, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Accession | Description | Average atg8∆/H99 |

|---|---|---|

| CNAG_06324 | Zinc finger protein Zfp2 | 2.070858 |

| CNAG_02541 | Cyclin-dependent protein kinase inhibitor | 1.476625 |

| CNAG_04668 | Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2M (Ubc12) | 1.471343 |

| CNAG_03759 | Conidiation-specific protein 6 | 1.453521 |

| CNAG_02257 | GTP-binding nuclear protein | 1.424417 |

| CNAG_06899 | 26S proteasome regulatory subunit N7 | 1.379142 |

| CNAG_01362 | Cell cycle control protein Cwf19 | 1.368171 |

| CNAG_02148 | Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 35, variant | 1.301707 |

| CNAG_05747 | Vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein Vta1 | 1.300065 |

| CNAG_00508 | Vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein Vps17 | 1.234959 |

| CNAG_05645 | COP9 signalosome complex subunit 3 | 1.215435 |

| CNAG_02167 | Vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein Vps27 | 1.228184 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fan, C.-L.; Li, L.; Shi, J.-C.; Liu, T.-B. The Zinc Finger Protein Zfp2 Regulates Cell–Cell Fusion and Virulence in Cryptococcus neoformans. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 868. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120868

Fan C-L, Li L, Shi J-C, Liu T-B. The Zinc Finger Protein Zfp2 Regulates Cell–Cell Fusion and Virulence in Cryptococcus neoformans. Journal of Fungi. 2025; 11(12):868. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120868

Chicago/Turabian StyleFan, Cheng-Li, Lin Li, Ji-Chong Shi, and Tong-Bao Liu. 2025. "The Zinc Finger Protein Zfp2 Regulates Cell–Cell Fusion and Virulence in Cryptococcus neoformans" Journal of Fungi 11, no. 12: 868. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120868

APA StyleFan, C.-L., Li, L., Shi, J.-C., & Liu, T.-B. (2025). The Zinc Finger Protein Zfp2 Regulates Cell–Cell Fusion and Virulence in Cryptococcus neoformans. Journal of Fungi, 11(12), 868. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120868