The Institutionalisation of Brazilian Older Abused Adults: A Qualitative Study among Victims and Formal Carers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Setting

2.3. Participants and Recruitment

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Analysis

2.6. Study Rigour

2.7. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Characteristics

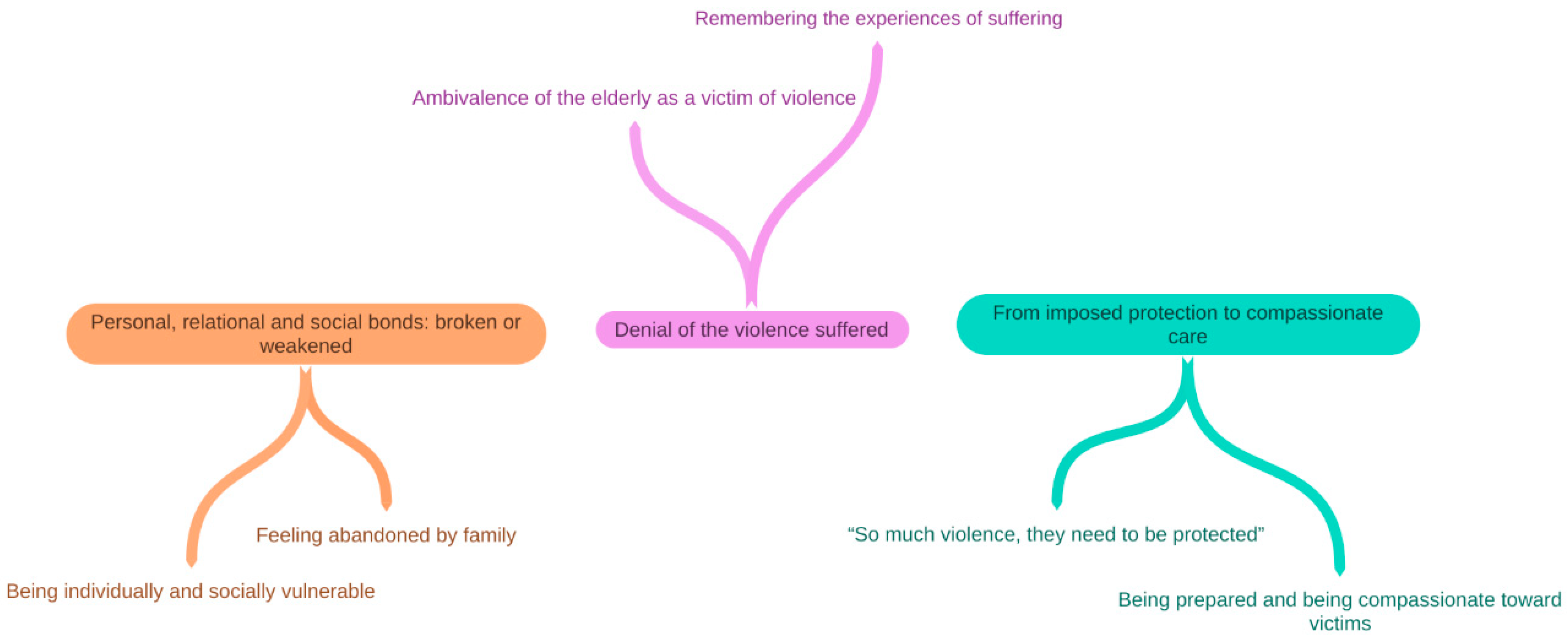

3.2. Findings from Thematic Analysis

3.2.1. Personal, Relational, and Social Bonds: Broken or Weakened

Being Individually and Socially Vulnerable

My life was different after I got separated, my life ended. My children were moving away. (...) After this happened in my life, where did I end up? (...) I feel bad for her, for my ex-wife, because I’m only here because of her. If what happened in my life hadn’t happened, I wouldn’t be here, I’d be at my house... she cheated on me because I drank.(OV-1)

When my son was 20, he left home, used drugs and I was sad. Today he has schizophrenia because of drugs, my wife left, and he lives in a health centre (...), now it’s up to me. When I think about my story, I realise the difficult environment I lived in.(OV-7)

Some of the cases that arrive at the institution are situations of enormous vulnerability, most of them motivated by the weak family and social support network, in addition to extreme poverty.(FC-2)

Feeling Abandoned by Family

I found my daughter again after a year of living here at home (...) I had no contact with my family. And I know that the home nurse insisted a lot on my daughter coming to visit me. Even so, I don’t always see her.(OV-1)

I feel abandoned by my family. Our relationship is not good, it’s like I don’t have brothers (...) I’ve always taken care of everyone, now they don’t even visit me.(OV-3)

I didn’t have much contact with my family, sometimes I saw my brother passing by on the street because he lived close by. I just miss the people I know, who would have breakfast at my house, I am grateful for them, they were the only ones who helped me.(OV-8)

3.2.2. Denial of the Violence Suffered

Ambivalence of the Elderly as Victims of Violence

I haven’t seen my children for a long time, but there was no violence! I came by my own will.(OV-1)

I never experienced violence. I came to live here because I had already lived with all my brothers and it didn’t work out, we fought a lot and I thought it was better to come to live here.(OV-6)

There was no violence, my family just doesn’t remember I exist. When they brought me to live in the home, I lived alone. My sister kept my bank card and I had nothing at home. The home staff already knew me and brought me food.(OV-3)

There was no problem in the family. I feel sorry for my son and my sister, because, when I needed it most, they referred me to other people to take care of me.(OV-7)

My daughter sometimes offended me… I didn’t like it, but I never dared to talk about it with anyone… it was a family matter, but it reached a limit.(OV-2)

Remembering the Experiences of Suffering

There are things in life that are not good to remember... and the doctor asked me to practice this because it doesn’t matter anymore.OV-4)

(...) I was afraid of being alone, on the other hand, I felt like a burden to them.(OV-6)

3.2.3. From Imposed Protection to Compassionate Care

“So Much Violence, They Need to Be Protected”

Suffering violence caused by children is terrible, I think there is nothing worse. We have an older woman who suffered sexual violence and the perpetrator was her brother. These occurrences hurt us. We have cases of aggression, both verbal and physical, false imprisonment (...) in short, violence of all kinds, always caused by the family.(FC-2)

Most of the time, families are the ones who abuse the elderly, and here we deal with all types of violence: psychological, financial, physical, and abandonment. So much violence, they need to be protected. We do everything to restore the health of the elderly and their joy of life. Most of the time, we succeed.(FC-3)

The older people we welcome arrive very weak, sick, scared, and in subhuman hygiene conditions. Everyone needed to be institutionalised because no other previous assistance was provided (...) so it got to the point it was.(FC-1)

I ate what I could cook (...) I walked with difficulty and the doctor said that I could no longer live alone, because of my health, but I had nowhere to go, I paid rent and the son of the owner of the house I rented, he helped me.(OV-5)

I think that in some cases something else could have been done, it could have been useful to help the family (...) the professionals could help with the care of the elderly at home, without having to separate them from the home environment. After suffering violence, it is necessary to take them away from the family. Some cases that are here in the hospital are those who were in a situation of abandonment l, and really needed to be institutionalised to be able to live with dignity.(FC-1)

I understand that other measures could be taken before the admission, such as helping with care at home and close to the family or even bringing the family closer together before definitive separation, as they suffer a lot in the adaptation period. Institutionalisation is full of prejudice, especially by the elderly.(FC-2)

Being Prepared and Being Compassionate toward Victims

I realise that the management of the secretariat [of the Ministry of Health] sometimes does not understand the complexity of these services. Our training is every day, it is part of the work routine. We make our observations and discuss the cases together, in this way, the care improves.(FC-2)

The work is not easy, but I notice that the team is very engaged and cares with love, everyone does a little more (...) The cases are so serious that many are referred for immediate care by the office for the elderly.(FC-4)

Most servers relate well with the elderly, treat them with affection, talk, and have patience. (…) I’m enjoying it, I feel good. I like to take care of the elderly.(FC-3)

4. Discussion

4.1. Study Limitations

4.2. Implications for Practice

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations; Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Leaving no One Behind in an Ageing World: World Social Report 2023; United Nations Publication: New York, NY, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2023/01/2023wsr-fullreport.pdf (accessed on 11 February 2023).

- Ministério da Saúde. Brasília, DF: Ministério da Saúde. 2020. Available online: https://datasus.saude.gov.br (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Nunes, E.P.O.; Pacheco, L.R. O processo saúde doença da pessoa idosa em situação de violência. Rev. Human Inov. 2018, 5, 240–251. [Google Scholar]

- Myhre, J.; Saga, S.; Malmedal, W.; Ostaszkiewicz, J.; Nakrem, S. Elder abuse and neglect: An overlooked patient safety issue. A focus group study of nursing home leaders’ perceptions of elder abuse and neglect. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.H.; Han, S.S.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, E.C.; Lee, E.H.; Park, J.O.; Lee, C.A. Clinical characteristics associated with physical violence in the elderly: A retrospective multicenter analysis. Iran J. Public Health 2022, 51, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pillemer, K.; Burnes, D.; Riffin, C.; Lachs, M.S. Elder Abuse: Global Situation, Risk Factors, and Prevention Strategies. Gerontologist 2016, 56 (Suppl. S2), S194–S205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blay, S.L.; Laks, J.; Marinho, V.; Figueira, I.; Maia, D.; Coutinho, E.S.F.; Quintana, I.M.; Mello, M.F.; Bressan, R.A.; Mari, J.J.; et al. Prevalence and correlates of elder abuse in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2017, 65, 2634–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ally, E.Z.; Laranjeira, R.; Viana, M.C.; Pinsky, I.; Caetano, R.; Mitsuhiro, S.; Madruga, C.S. Intimate partner violence trends in Brazil: Data from two waves of the Brazilian National Alcohol and Drugs Survey. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2016, 38, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pampolim, G.; Leite, F.M.C. Analysis of repeated violence against older adults in a Brazilian state. Aquichan 2021, 21, e2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Elder Abuse: Key Facts; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/abuse-of-older-people (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Machado, D.R.; Kimura, M.; Duarte, Y.A.O.; Lebrão, M.L. Violência contra idosos e qualidade de vida relacionada à saúde: Estudo populacional no município de São Paulo, Brasil. Cienc. Saúde Coletiva 2020, 25, 1119–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, E.S.; Levy, B.R. High prevalence of elder abuse during the COVID-19 pandemic: Risk and resilience factors. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2021, 29, 1152–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W. Perceptions of elder abuse and neglect by older Chinese immigrants in Canada. J. Elder Abuse Negl. 2019, 31, 340–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yon, Y.; Mikton, C.R.; Gassoumis, Z.D.; Wilber, K.H. Elder abuse prevalence in community settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2017, 5, e147–e156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yon, Y.; Ramiro-Gonzalez, M.; Mikton, C.R.; Huber, M.; Sethi, D. The prevalence of elder abuse in institutional settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Public Health. 2019, 29, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, F.D.S.; de Lima Saintrain, M.V.; de Souza Vieira, L.J.E.; Gomes Marques Sampaio, E. Characterization and Prevalence of Elder Abuse in Brazil. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, NP3803–NP3819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludvigsson, M.; Wiklund, N.; Swahnberg, K.; Simmons, J. Experiences of elder abuse: A qualitative study among victims in Sweden. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koller, S.H.; dos Santos Paludo, S.; de Morais, N.A. (Eds.) Ecological Engagement: Urie Bronfenbrenner’s Method to Study Human Development; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teaster, P.B. A framework for polyvitimization in later life. J. Elder Abuse Negl. 2017, 29, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, V.M.; Scofield, A.M.T.S.; Alcântara, R.K.L.; Fernandes, B.K.C.; Leite, S.F.P.; Borges, C.L. What taken the elderly people to institutionalization? Rev. Enferm. UFPE 2018, 12, 2428–2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, S.B.; Skolbekken, J.A.; Mosqueda, L.; Malmedal, W. Making Neglect Invisible: A Qualitative Study among Nursing Home Staff in Norway. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielewicz, A.L.; Wagner, K.J.P.; Orsi, E.; Boing, A.F. Is cognitive decline in the elderly associated with contextual income?: Results of a population-based study in Southern Brazil. Cad. Saúde Pública 2016, 32, e00112715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldblatt, H.; Band-Winterstein, T.; Alon, S. Social workers’ reflections on the therapeutic encounter with elder abuse and neglect. J. Interpers. Violence 2018, 33, 3102–3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, A.; Williams, J.; Wydall, S. Access to Justice for Victims/Survivors of Elder Abuse: A Qualitative Study. Soc. Policy Soc. 2016, 15, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hu, F. Elder abuse in life stories: A qualitative study on rural Chinese older people. J. Elder Abuse Negl. 2021, 33, 206–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wangmo, T.; Teaster, P.B.; Grace, J.; Wong, W.; Mendiondo, M.S.; Blandford, C.; Fisher, S.; Fardo, D.W. An ecological systems examination of elder abuse: A week in the life of adult protective services. J. Elder Abuse Negl. 2014, 26, 440–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiamberg, L.B.; Barboza, G.G.; Oehmke, J.; Zhang, Z.; Griffore, R.J.; Weatherill, R.P.; von Heydrich, L.; Post, L.A. Elder abuse in nursing homes: An ecological perspective. J. Elder Abuse Negl. 2011, 23, 190–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lund, S.B.; Skolbekken, J.A.; Mosqueda, L.; Malmedal, W.K. Legitimizing neglect–A qualitative study among nursing home staff in Norway. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storey, J.E. Risk factors for elder abuse and neglect: A review of the literature. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2020, 50, 101339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikton, C.; Beaulieu, M.; Yon, Y.; Genesse, J.C.; St-Martin, K.; Byrne, M.; Phelen, A.; Storey, J.; Rogers, M.; Campbell, F.; et al. PROTOCOL: Global elder abuse: A mega-map of systematic reviews on prevalence, consequences, risk and protective factors and interventions. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2022, 18, e1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenny, S.; Brannan, J.M.; Brannan, G.D. Qualitative Study. In StatPearls. Treasure Island; StatPearls Publishing: Tampa, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care. 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Maringá. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE. 2021. Available online: https://www.ibge.gov.br/cidades-e-estados/pr/maringa.html (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Health at a Glance. Ageing and Long-Term care. OECD. 2021. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/c8078fff-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/c8078fff-en (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- United Nations UN. UN Decade of Healthy Ageing 2020–2030: Plan of Action; United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Melo, D.M.; Barbosa, A.J.G. O uso do Mini-Exame do Estado Mental em pesquisas com idosos no Brasil: Uma revisão sistemática. Cienc. Saúde Coletiva 2015, 20, 3865–3876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rädiker, S.; Kuckartz, U. Analyse Qualitativer Daten Mit MAXQDA; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orfila, F.; Coma-Solé, M.; Cabanas, M.; Cegri-Lombardo, F.; Moleras-Serra, A.; Pujol-Ribera, E. Family caregiver mistreatment of the elderly: Prevalence of risk and associated factors. BMC Public Health. 2018, 18, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesari, M.; Prince, M.; Thiyagarajan, J.A.; Carvalho, I.A.; Bernabei, R.; Chan, P.; Gutierrez-Robledo, L.M.; Michel, J.-P.; Morley, J.E.; Ong, P.; et al. Frailty: An emerging public health priority. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2016, 17, 188–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bows, H. Sexual violence against older people: A review of the empirical literature. Trauma Violence Abuse 2018, 19, 567–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, D.; Wood, S.; Mitis, F.; Bellis, M.; Penhale, B.; Marmolejo, I.I.; Lowenstein, A.; Manthorpe, G.; Karki, F.U. European Report on Preventing Elder Maltreatment. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/107293 (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Medeiros, F.A.L.; Oliveira, J.M.M.; Lima, R.J.; Nóbrega, M.M.L. The care for institutionalized elderly perceived by the nursing team. Rev. Gaúcha Enferm. 2015, 36, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnes, D.; Lachs, M.; Burnette, D.; Pillemer, K. Varying Appraisals of Elder Mistreatment Among Victims: Findings from a Population-Based Study. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2019, 74, 881–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blix, I.; Brennen, T. Intentional forgetting of emotional words after trauma: A study with victims of sexual assault. Front. Psychol. 2011, 2, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyadurai, L.; Visser, R.M.; Lau-Zhu, A.; Porcheret, K.; Horsch, A.; Holmes, E.A.; James, E.L. Intrusive memories of trauma: A target for research bridging cognitive science and its clinical application. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 69, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciurria, M. The Loss of Autonomy in Abused Persons: Psychological, Moral, and Legal Dimensions. Humanities 2018, 7, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. Autonomy, Gender, Politics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-García, S.; García-Peña, C.; Ramírez-García, E.; Moreno-Tamayo, K.; Cantú-Quintanilla, G.R. Decreased Autonomy In Community-Dwelling Older Adults. Clin. Interv. Aging 2019, 14, 2041–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, L.A.L.; Dias, F.A.; Marchiori, G.F.; Gomes, N.C.; Corradini, F.A.; Tavares, D.M.S. Violence against the elderly people: Predictors and space distribution. Cienc. Cuid. Saúde. 2019, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moilanen, T.; Kangasniemi, M.; Papinaho, O.; Mynttinen, M.; Siipi, H.; Suominen, S.; Suhonen, R. Older people’s perceived autonomy in residential care: An integrative review. Nurs. Ethics 2021, 28, 414–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolkan, C.; Teaster, P.B.; Ramsey-Klawsnik, H. The Context of Elder Maltreatment: An Opportunity for Prevention Science. Prev. Sci. 2023, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Estatuto do Idoso, 3rd ed.; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, DF, Brazil, 2013. Available online: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/estatuto_idoso_3edicao.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Ranabhat, P.; Nikitara, M.; Latzourakis, E.; Constantinou, C.S. Effectiveness of Nurses’ Training in Identifying, Reporting and Handling Elderly Abuse: A Systematic Literature Review. Geriatrics 2022, 7, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmons, J.; Wiklund, N.; Ludvigsson, M. Managing abusive experiences: A qualitative study among older adults in Sweden. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Elders |

|

|

| LTC Workers |

|

|

| Variables | Elders | LTC Workers |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) mean (SD; range) | 74.25 ± 7.22 (60–85) | 48.1 ± 10.65 (31–63) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 4 | 0 |

| Female | 4 | 10 |

| Years of schooling | ||

| <8 years | 7 | 0 |

| ≥8 years | 1 | 10 |

| Income | ||

| <1 minimum wage † | 8 | 0 |

| ≥1 minimum wage | 0 | 10 |

| Time in LSIE | ||

| <1 year 1–5 years | 2 5 | 0 6 |

| 6–10 years 11–15 years | 1 0 | 3 0 |

| ≥16 years | 0 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ribeiro, D.; Carreira, L.; Salci, M.A.; Marques, F.R.D.M.; Gallo, A.; Baccon, W.; Baldissera, V.; Laranjeira, C. The Institutionalisation of Brazilian Older Abused Adults: A Qualitative Study among Victims and Formal Carers. Geriatrics 2023, 8, 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics8030065

Ribeiro D, Carreira L, Salci MA, Marques FRDM, Gallo A, Baccon W, Baldissera V, Laranjeira C. The Institutionalisation of Brazilian Older Abused Adults: A Qualitative Study among Victims and Formal Carers. Geriatrics. 2023; 8(3):65. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics8030065

Chicago/Turabian StyleRibeiro, Dayane, Lígia Carreira, Maria Aparecida Salci, Francielle Renata Danielli Martins Marques, Adriana Gallo, Wanessa Baccon, Vanessa Baldissera, and Carlos Laranjeira. 2023. "The Institutionalisation of Brazilian Older Abused Adults: A Qualitative Study among Victims and Formal Carers" Geriatrics 8, no. 3: 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics8030065

APA StyleRibeiro, D., Carreira, L., Salci, M. A., Marques, F. R. D. M., Gallo, A., Baccon, W., Baldissera, V., & Laranjeira, C. (2023). The Institutionalisation of Brazilian Older Abused Adults: A Qualitative Study among Victims and Formal Carers. Geriatrics, 8(3), 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics8030065