1. Introduction

Throughout the course of our lives, we are constantly exposed to negative societal views and stereotypes about older adults, from subtle ageist jokes in conversations to instances in which individuals are labeled as burdensome or unproductive members of society. These perspectives are assimilated and give rise to explicit and implicit assumptions about aging, older individuals, and what it means to be old [

1,

2,

3]. These assumptions form the foundation of ageism: discrimination, stereotyping, or prejudices against older individuals (even among themselves) based solely on age [

4]. Ageism has become a growing global concern as repeated exposure to ageism can have serious negative consequences for older individuals’ self-perceptions of their aging process [

5,

6] (e.g., through the internalization of stereotypes) and, subsequently, their overall quality of life and mental well-being, as well as depressive symptomatology and feelings of loneliness (e.g., [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]).

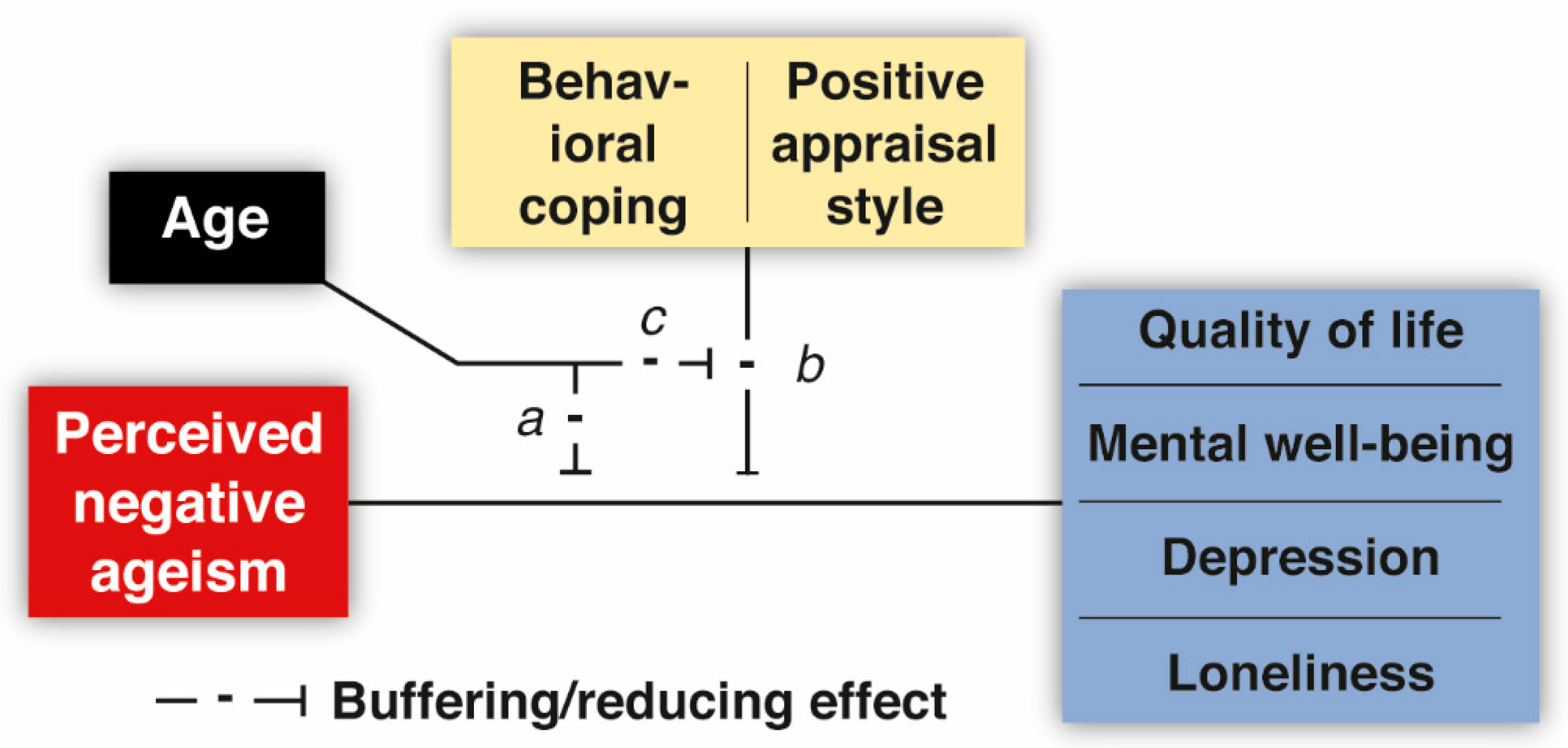

However, not everyone seems to be equally affected by ageism [

14]. Resilience, the ability to effectively cope with and adapt to difficult or challenging life experiences [

15], may play a critical role in mitigating or even neutralizing the detrimental impact of ageism. Yet it is relatively unknown which resources or factors may provide such protection and render some individuals better equipped than others to deal with the challenges of perceiving and experiencing ageism. Gaining such insights is crucial for identifying who is the most vulnerable and for determining how older adults may (be supported to) safeguard themselves against the harmful impact of ageism. To address this knowledge gap, the present study examined to what extent two factors related to coping as fundamental aspects of resilience—behavioral coping and a positive appraisal style—could buffer the relationship between perceived negative ageism (i.e., the stressor) and older individuals’ quality of life and mental well-being, as well as their levels of depression and loneliness. We also explored several resilience-related factors (e.g., self-efficacy, social participation; see the

Supplementary Materials, Supplement S1). Unlike behavioral coping and a positive appraisal style, which pertain to immediate specific responses/mechanisms to deal with stressors, these additional factors are thought to operate at a broader and more generalized level, influencing a person’s overall ability to manage stress effectively.

Several systematic reviews and meta-analyses have identified resilience as a factor with significant protective potential for the (mental) health of older adults (e.g., [

16]). However, to date, only a limited number of studies have sought to ascertain which specific factors may provide such resilience (or a buffering effect) against the negative effects of ageism (for a review of all studies before 2022, see [

17,

18,

19]). Many of these studies considered resilience factors as mediators. This allows for an examination of (1) the extent to which ageism weakens potential resilience factors (e.g., the subjective ability to bounce back after stressful life-events [

19]), thereby compromising psychological well-being; and (2) the extent to which ageism enhances certain aspects that can positively impact mental health (e.g., stronger group identification [

9]), thus shedding light on the processes through which certain factors may dampen the negative effects of ageism. However, these approaches do not elucidate the resources that may alleviate or neutralize the harmful effects of ageism. Hence, adopting a moderation design in which resilience factors act as adequate stress moderators that are not necessarily affected by ageism directly seems more opportune for the current aim and will therefore be the focus of this study.

Some studies have evaluated resilience-related moderators of ageism—(mental) health association, including self-esteem [

18]; sense of control [

20]; optimism [

21]; and positive self-perceptions of aging and/or feeling younger [

22]. However, as of yet, the potential moderating effect of adequate coping, which is instrumental to an individual’s ability to adapt and rebound from adversity, in relation to perceived ageism has received minimal attention. Coping encompasses both behavioral and cognitive strategies employed by individuals to manage internal and external demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding personal resources [

23,

24]. Behavioral coping strategies include instrumental support seeking, emotional support seeking, the venting of emotions, and planning or acting out (i.e., devising a plan of action/considering which steps to take). These strategies provide individuals with tangible and actionable approaches to dealing with stressors and have been recommended for preventing stress-related issues associated with aging and promoting successful aging [

25]. Within the realm of cognitive coping, different strategies can be identified based on their underlying cognitive processes and goals. Some of these strategies are specifically oriented toward positive appraisal and involve cognitive processes that promote positive interpretations and evaluations of stressors (e.g., through positive reappraisal, humor, acceptance, and putting things into perspective or by refocusing on planning [

26]). Individuals who tend to appraise potentially threatening or stressful situations in a positive way are thought to have a positive appraisal style. A positive appraisal style can help individuals reframe stressors as manageable challenges and is considered a crucial factor in mitigating the association between stressor exposure and increased levels of psychological distress or mental health problems [

27].

Several behavioral and cognitive coping strategies have previously been suggested to forestall the negative effects of perceived racism (or racial discrimination) on (mental) health [

28]; similarly, examining the role of coping as potential moderator of the negative effects of perceived ageism seems highly relevant. Therefore, in a large sample of older adults (N = 2000), we investigated whether the tendency to adopt behavioral coping strategies and embrace a positive appraisal style could buffer against the adverse effects of ageism on quality of life, mental well-being, depression, and loneliness (

Box 1). This may reveal valuable insights for interventions and personal efforts aimed at shielding individuals from the harmful impact of ageism.

Box 1. Outcome Variables of Interest.

Quality of life refers to the cognitive appraisal of one’s life, while mental well-being reflects the emotional response to what life is like [

29]. Depression, a common mental health disorder, is characterized by persistent feelings of sadness, hopelessness, and a loss of interest or pleasure in activities [

30]. Loneliness, on the other hand, refers to a subjective feeling of social isolation or a lack of meaningful connections with others [

31]. Although both quality of life and mental well-being are influenced by depressive symptoms and loneliness, these mental-health-related variables also exhibit distinct characteristics. By evaluating these outcome variables separately, we can inform more tailored interventions to support older individuals in navigating the challenges posed by ageism.

Individuals who tend to adopt behavioral coping strategies when dealing with stressful or challenging experiences may be better equipped to deal with ageism-related distress. Behavioral coping strategies could enable individuals to question the validity of ageist beliefs directed at them (e.g., by discussing the experience with a friend) and reduce negative feelings about oneself. Similarly, those who have a positive appraisal style may be more likely to mitigate or neutralize their negative thoughts derived from negative ageism experiences, thereby reducing the chance that ageism experiences will exert an enduring impact on their quality of life and mental well-being and/or will cause heightened levels of depressive symptomatology or feelings of loneliness. Both the use of behavioral coping strategies and the extent to which one positively appraises stressful situations have been claimed to be modifiable [

27,

32,

33,

34] and may therefore provide opportune target points for interventions or personal efforts aimed at promoting adequate coping with negative ageism experiences.

The benefits of these coping styles may also vary with age. While the level of perceived ageism tends to increase with age [

7,

35], an increasing number of studies suggest that ageism may be more harmful to relatively younger seniors (e.g., [

12,

36,

37]). This has been attributed to the fact that ageism becomes more self-relevant in middle age and that facing ageism may have been neglected as a remote future experience and even serves as a “rude awakening” that conflicts with individuals’ (positive) self-image and expectations of the future, thereby causing the most distress during this life phase [

36,

38]. In contrast, older-older adults may be more likely to accept or have already internalized age-related stereotypes [

39] and/or even perceive ageism as legitimate [

40]. Moreover, older age could offer some protection against the harmful effects of ageism as older adults may have developed a larger repertoire of coping strategies from dealing with previous experiences of ageism, which provides resilience for subsequent exposure [

41]. Altogether, it seems plausible that especially those younger in age may benefit from high levels of the protective resilience factors of interest; therefore, the role of age in moderating the potential benefits of the resilience factors of interest was also examined.

Specifically, in this study, we set out to test several hypotheses. First, we hypothesized that there would be a negative/unfavorable relationship between perceived negative ageism and quality of life and mental well-being, depression, and loneliness. Second, we examined the moderating role of age in these associations, anticipating weaker links for older individuals. Third, we expected a neutralizing/buffering effect of behavioral coping and a positive appraisal style on the relationship between perceived negative ageism and the outcome variables of interest. Finally, we hypothesized that age moderates the buffering/neutralizing effect of these resilience factors such that especially those younger in age were expected to benefit from high levels of resilience factors.

4. Discussion

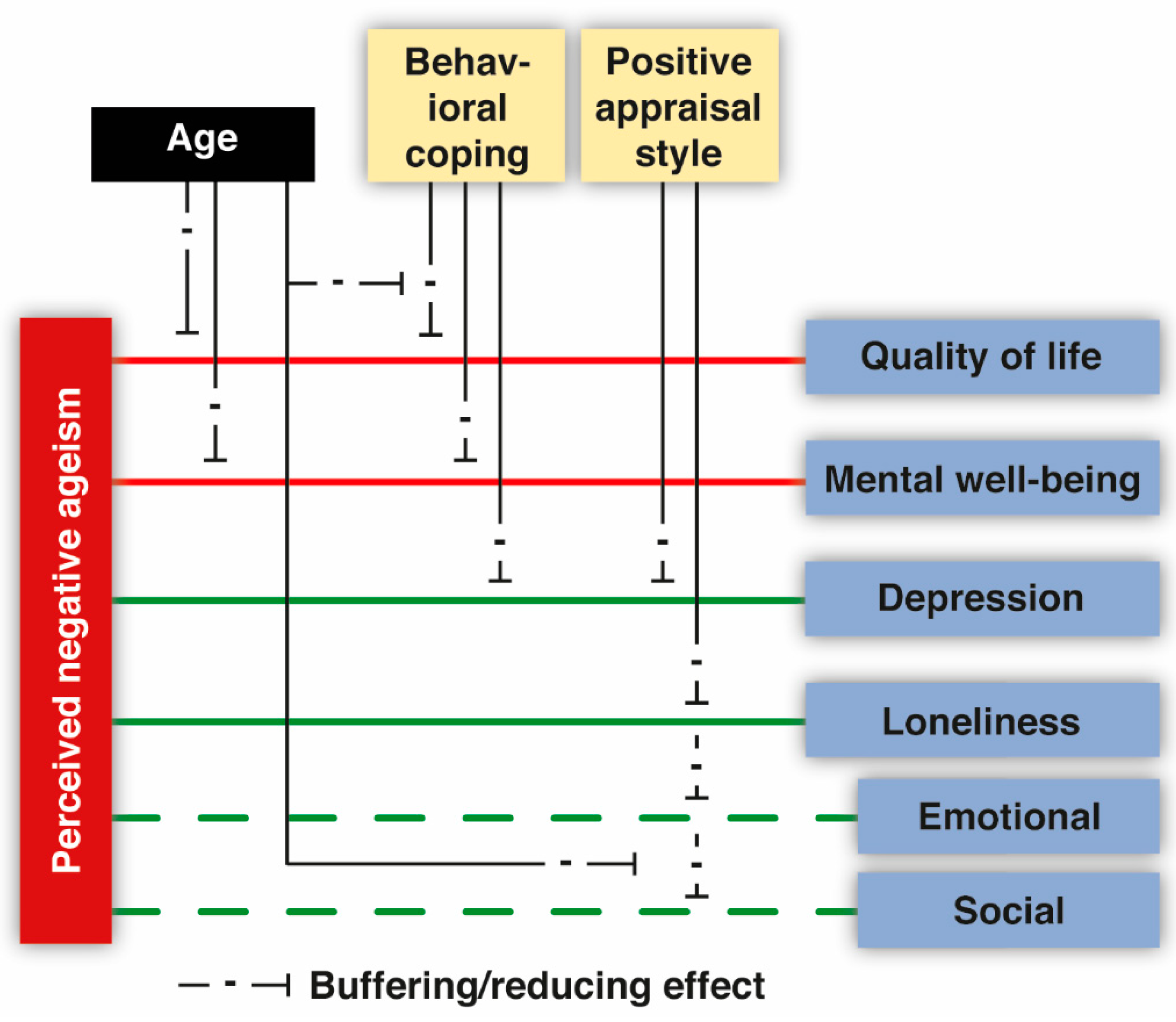

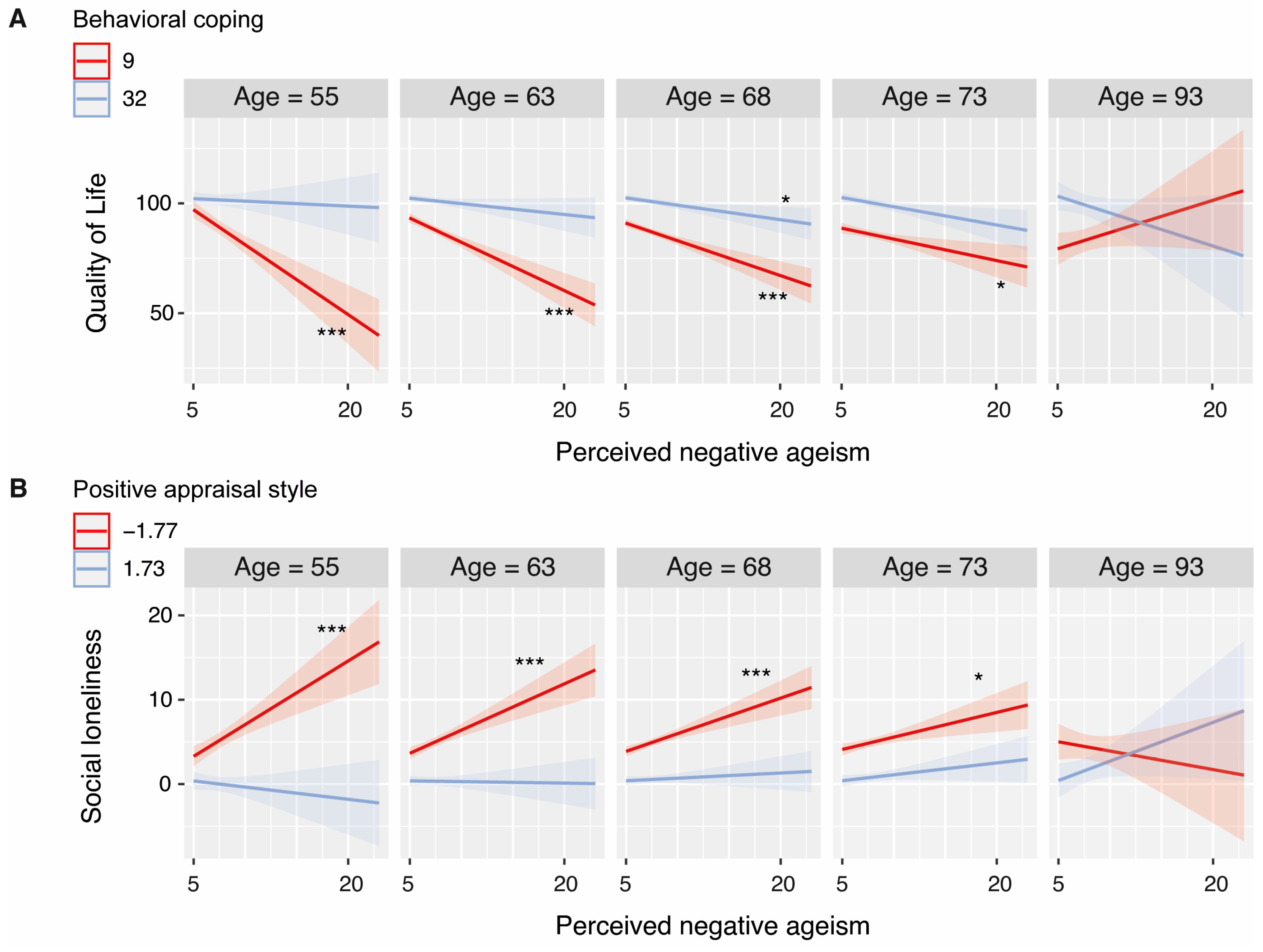

Frequent exposure to ageism can have negative implications for older individuals’ (aged 55 years or older) quality of life, mental well-being, and mental health. However, individual responses to perceived ageism vary widely, suggesting that individual differences in resilience may play a crucial role. In line with the notion that adequate coping equips individuals with the skills, mindset, and emotional strength to effectively face and navigate adversity, the present study suggests that adequate coping can alleviate and sometimes even neutralize the negative effects of perceived negative ageism (PNA), especially among older adults who are relatively young. Specifically, we found that behavioral coping mitigated the negative effects of PNA on quality of life, mental well-being, and depression but not loneliness. A positive appraisal style buffered the relationship between PNA and both depression and loneliness. The most important findings and their relevant nuances are discussed below.

4.1. Ageism Seems Particularly Harmful for Those Younger in Age

Although the level of PNA increased with age [

7,

35], the negative relationships between PNA and both quality of life and mental well-being became less pronounced with increasing age. This is in line with our hypothesis and numerous previous studies (e.g., [

12,

36,

37]), and concurs well with the idea that ageism may be particularly harmful when it becomes self-relevant for the first time [

36,

38]. Moreover, it aligns with earlier suggestions that older-older adults may have assimilated and internalized age-related stereotypes [

39] and may even perceive ageism as legitimate [

40]. In addition, or alternatively, these findings could be driven by older individuals being better equipped to navigate ageism because they have developed knowledge and adaptive coping strategies throughout their life [

78] other than those specified as behavioral coping or a positive appraisal style in the present study (e.g., finding or creating meaning and purpose in challenging or difficult situations, being assertive in expressing needs and boundaries, and/or critical thinking to challenge stereotypes and advocate for fair treatment). Surprisingly, no moderating effects of age surfaced in relation to depression and loneliness, implying that high levels of perceived ageism contribute to higher levels of depression and loneliness independent of age. Given that the level of PNA increased with age, it remains evident that older-older adults may be less severely affected by PNA, but the negative consequences for their mental health are likely not entirely averted. Age also moderated the extent to which behavioral coping and a positive appraisal style buffered the negative relationship between PNA and some outcome variables. These findings will be discussed in the next section.

4.2. Behavioral Coping

Behavioral coping appears to be a promising factor in mitigating the negative effects of ageism. Indeed, previous research on discrimination and health already suggested that coping behaviors can moderate the link between perceived racial discrimination and (mental) health [

28]. The present study adds to our understanding and shows that behavioral coping behaviors may also protect individuals from ageism effects specifically. The potential moderating effect of one specific adaptive behavioral coping strategy, namely seeking social support/advice from family, relatives, and friends, was previously examined by Kim and colleagues [

79]. They reported beneficial effects of this behavioral coping strategy in mitigating the negative relationship between emotional responses caused by ageism experiences and depression. Our findings extend these results and show that other behavioral coping strategies may also prove to be effective, not only for neutralizing PNA’s effects on depression but also for quality of life and mental well-being.

Interestingly, for quality of life, the potential of behavioral coping as resilience factor seemed to decrease with age, which suggests that younger individuals in particular could benefit from seeking instrumental or emotional support, venting their emotions, and planning or acting out. This can be explained by the fact that while PNA is encountered more frequently at higher ages, the detrimental consequences of PNA decrease with age, rendering additional efforts in the form of coping less imperative (note that both behavioral coping and a positive appraisal style were negatively associated with age). Additionally, it may, at least partially, be explained by the fact that the deployment of behavioral coping strategies often requires the involvement of others, while social networks tend to decline with age [

80]. In support of this, we found that behavioral coping was more strongly associated with age than positive appraisal style was. Hence, younger individuals may benefit from larger social networks they can resort to, enabling them to use behavioral coping as a strategy to deal with ageism distress and thereby protecting their quality of life. Why this is particularly true for quality of life remains an important question. While the effect of PNA on mental well-being also seemed to decrease with age, behavioral coping appeared to neutralize PNA’s negative relationship with mental well-being similarly across all age groups.

While behavioral coping seemed to buffer PNA’s effects on depression, feelings of loneliness were not harnessed by these strategies. In line with previous argumentations and the observation that greater feelings of loneliness were associated with low levels of behavioral coping, behavioral coping may be less effective at protecting against increases in loneliness if a reduction in social connections prevents one from employing behavioral coping as useful strategy. Moreover, we may speculate that behavioral coping strategies are less effective in buffering ageism’s impact on loneliness if individuals resort to their social network but subsequently encounter social interactions that are characterized by rejection, exclusion, or a lack of understanding. This speculation calls for deeper investigation, including regarding the reasons why this pattern does not seem to hold true for quality of life and depression.

Altogether, these findings lend support to our hypotheses concerning the buffering/neutralizing impact of behavioral coping on perceived negative ageism’s influence on quality of life, mental well-being, and depression, albeit not on loneliness. While younger individuals seem to benefit more strongly from high levels of behavioral coping, the evidence concerning this hypothesis is less conclusive across all outcome variables.

4.3. Positive Appraisal Style

A positive appraisal style mitigated the harmful effects of ageism on depression and loneliness. This is in line with an earlier study reporting the benefit of optimism in moderating the ageism–psychological distress link [

21] and suggests that this resilience factor is particularly beneficial in protecting against two of the most common mental health issues in later life. Indeed, positive appraisal concerns the (emotional) re-evaluation of a certain situation. Individuals who embrace a positive appraisal style are thought to appraise an adverse event or threat in a realistic or positive way, thereby avoiding catastrophizing, pessimism, and helplessness. When negative ageism is frequently encountered, this may help to prevent or neutralize intrusive and negative thoughts about the consequences of aging, contributing to more favorable mental health outcomes. That is, earlier research reported that those with more negative expectations about the aging process, or even those that associate old age with loneliness in later life, have a higher change of becoming lonely and depressed in the future [

81,

82]. Appraising ageist encounters in a non-negative way may prevent such negative trajectories (e.g., by reappraising it or putting it in perspective, for instance, by considering it a form of humor or by distancing oneself from ageist encounters by thinking “he/she is wrong to think this applies to me”).

Interestingly, while a positive appraisal style seemed to buffer the negative effects of PNA on emotional loneliness at all ages, we found preliminary evidence suggesting that the negative impact on feelings of social loneliness may only be neutralized by positive appraisal among relatively young individuals. Emotional loneliness pertains to the subjective experience of lacking intimate and meaningful emotional connections with others. Social loneliness, on the other hand, refers to a perceived absence or insufficiency of social interactions and companionship. These patterns may be explained by the fact that emotional connections remain important throughout the lifespan, while social loneliness may be particularly impactful for relatively young individuals who may place greater value on broad social networks [

83]. On the other hand, again, it may be that it is more challenging to alleviate PNA’s effects on social loneliness through positive appraisal as strategies like putting things in perspective or accepting the fact that certain individuals exhibit ageist attitudes may not necessarily lead to a substantial increase in the availability of social interactions—although it may help to reduce negative feelings about the ageist experience.

Altogether, these findings affirm our hypotheses regarding the buffering/neutralizing impact of a positive appraisal style on perceived negative ageism’s impact on depression and mental well-being, though not on the broader constructs of quality of life and mental well-being. Some instances suggest that age may play a moderating role, but this observation is, again, less conclusive.

4.4. Intervention Potential

Encouraging individuals to proactively address ageism-related stressors by seeking instrumental and emotional support, venting their emotions, or planning/acting out, as well as to embrace a positive appraisal style, may help individuals to reduce the toll of ageism and bolster their quality of life, mental well-being, and mental health. Several programs have proven effective in diminishing ageist perceptions among younger and older adults [

84]. However, as far as we know, there have been limited attempts to devise and test an intervention program that can help older individuals to cope with ageist experiences and challenge the validity of ageist perceptions directed at them. Jeste, Trechler, and their colleagues [

85,

86] describe one of the few resilience-promoting interventions for older adults that incorporated explicit discussions on the impact of age discriminations and stereotypes, along with methods to fight those stereotypes and improve perceptions of aging. Current findings suggest it may be promising to develop an intervention program or course that specifically focuses on promoting the use of behavioral coping strategies and cultivating a positive appraisal style as a means of empowering older individuals to mitigate the negative consequences of ageism. Surprisingly, despite previous recognition of coping strategies as possible targets for intervention in various stress-related contexts, there have been relatively few attempts to actively manipulate these factors to instigate real changes. Importantly, those few attempts have yielded promising results: specific behavioral coping strategies were successfully enhanced and positive appraisal style dimensions were fostered within the context of resilience and stress management [

34,

87,

88]. To illustrate this point, positive reappraisal among older individuals with a chronic physical illness was increased after learning how to effectively use this coping strategy, contributing to more positive emotions [

87,

88]. Hence, it seems opportune for future research to develop and test coping-based ageism interventions and identify by whom such programs may be delivered, and which settings are most appropriate (e.g., health care and community centers or assisted living facilities for seniors). Indeed, health-care professionals seem well-suited to administering such programs, either on an individual basis or as part of a group-based initiative.

4.5. Limitations and Future Directions

Despite these promising findings and the potential benefits of coping programs, it is imperative to acknowledge that not all observations are equally robust. For instance, while we established that age may be an important moderator of the buffering effect of behavioral coping for quality of life, it is worth noting that a relatively high number of bootstrap iterations showed no such moderation. Similarly, for a substantial number of bootstrapping iterations, no moderation effect for positive appraisal style was found for the PNA—depression link. This indicates that these outcomes were notably sensitive to the composition of participants in each subsample, which potentially limits the generalizability of these findings to some extent. This suggests that the patterns of interest are complex and might be contingent upon specific participant characteristics; potentially, the variation stems from factors that have not been accounted for and could imply that some (subgroups) of individuals do benefit from effective coping, whereas others do not. Indeed, our post hoc analysis provided some interesting nuances regarding the influence of gender. Specifically, our findings suggest that females may derive greater benefit from behavioral coping efforts and a positive appraisal style compared with males. Importantly, this discrepancy is not attributable to differences in the level of PNA or to a weaker association between PNA and the outcome variables (although for depression, the link with PNA was notably stronger among females, yet still evident among males). This suggests that on average, males may be more susceptible in the face of ageism and potentially derive fewer advantages from programs aimed at promoting behavioral coping and a positive appraisal style. These findings may be explained by gender differences in the effectiveness of employing these resilience factors. That is, women often experience multiple layers of discrimination due to the intersection of ageism with gender bias [

89]. These intersecting identities can lead women to develop enhanced resilience and coping strategies, making them more adept at using behavioural coping and positive appraisal styles when dealing with ageism. Future research may dive further into these subgroup patterns and potential explanations thereof and use a confirmatory study design to replicate current exploratory findings. Furthermore, the role of other factors that could influence the benefits of behavioral coping and a positive appraisal style, including cultural differences, socio-economic status, health conditions, or the presence of other major life stressors, should also be explored. Indeed, the current sample was highly educated, and different patterns may arise when less educated participants are included.

In any case, the uncertainty of some of our findings emphasizes that the negative effects of ageism may be somewhat resistant, at least to some individuals, and that it can be challenging to mitigate these effects. This conclusion is also supported by the series of exploratory analyses that we conducted. We explored the role of several distal resilience factors, including self-efficacy, self-esteem, social participation, and several personality traits. As reported in the

Supplementary Materials, Supplement S1, we did not find convincing evidence for strong buffering effects of any of these factors, suggesting that overall, the effects of negative ageism remain largely exempt from moderation by these distal resilience factors. Altogether, this underscores that despite some promising effects for adequate coping, resilience is not a panacea, and it remains of the utmost importance to combat the sources of ageism in society, as mitigating its effects may not be manageable for everyone.

The present study reports cross-sectional relationships and identifies the potential protective influence of various resilience factors on a broad time scale. However, perceived ageism may vary on a daily or weekly basis [

90]. An ageist encounter on a certain day may activate more negative self-perceptions of aging or lower levels of self-efficacy (or another mediating factor), which could directly impact one’s mental well-being or mood/mental health (e.g., more depressive symptoms). It is of great interest to determine if resilience factors, such as the tendency to use behavioral coping strategies and/or embrace a positive appraisal style, could mitigate these kinds of processes and at what stage(s) they may be able to intervene and/or regulate temporary declines in mood/well-being that could otherwise elevate the risk of escalating toward mental health issues in the long term.

Finally, given the subjective nature of perceived ageism, it is essential to acknowledge that the level of perceived ageism may not always align with the level of ageism that individuals are objectively exposed to. Although older individuals may encounter ageist attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors, they may not necessarily perceive or be aware of them, or they may erroneously perceive a comment as ageist. Such a discrepancy could result in varying levels of perceived ageism among older individuals, even if they are exposed to comparable levels of ageism objectively. Individual differences in (mental) health status or resilience mechanisms may play a crucial role in this context as well. For instance, research suggests that individuals who are depressed may be more likely to perceive high levels of ageism due to their negative outlook on life [

91]. Conversely, some resilience factors, such as those evaluated in the current study, may help to protect individuals from

perceiving ageism, even when they are exposed to it. For instance, individuals who have a positive appraisal style may inherently view the world more positively and thereby not perceive ageism objectively. Exploring these risk and protective factors may provide a comprehensive understanding of the subjective nature of perceived ageism and how to mitigate its impact, as well as reduce it on a societal level.

4.6. Summary

In summary, the current study shows that adequate coping may play a significant role in mitigating the deleterious effects of perceived ageism. Behavioral coping and a positive appraisal style both seem to be opportune target points for interventions to promote resilience against the impact of ageism, at least among older adults with higher education levels and especially among females. Moreover, those younger in age seem to benefit the most. Nonetheless, our findings also highlight that this may not work for every individual and that neutralizing the effects of perceived ageism can be extremely challenging. Even the most resilient older adults may still experience the negative impacts of ageism. Hence, in addition to enhancing resilience among older individuals, it remains highly important to address and ultimately reduce ageism at both individual and societal levels and to create a more equitable and inclusive society for people of all ages.