Isotretinoin Treatment for Autosomal Recessive Congenital Ichthyosis in a Golden Retriever

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

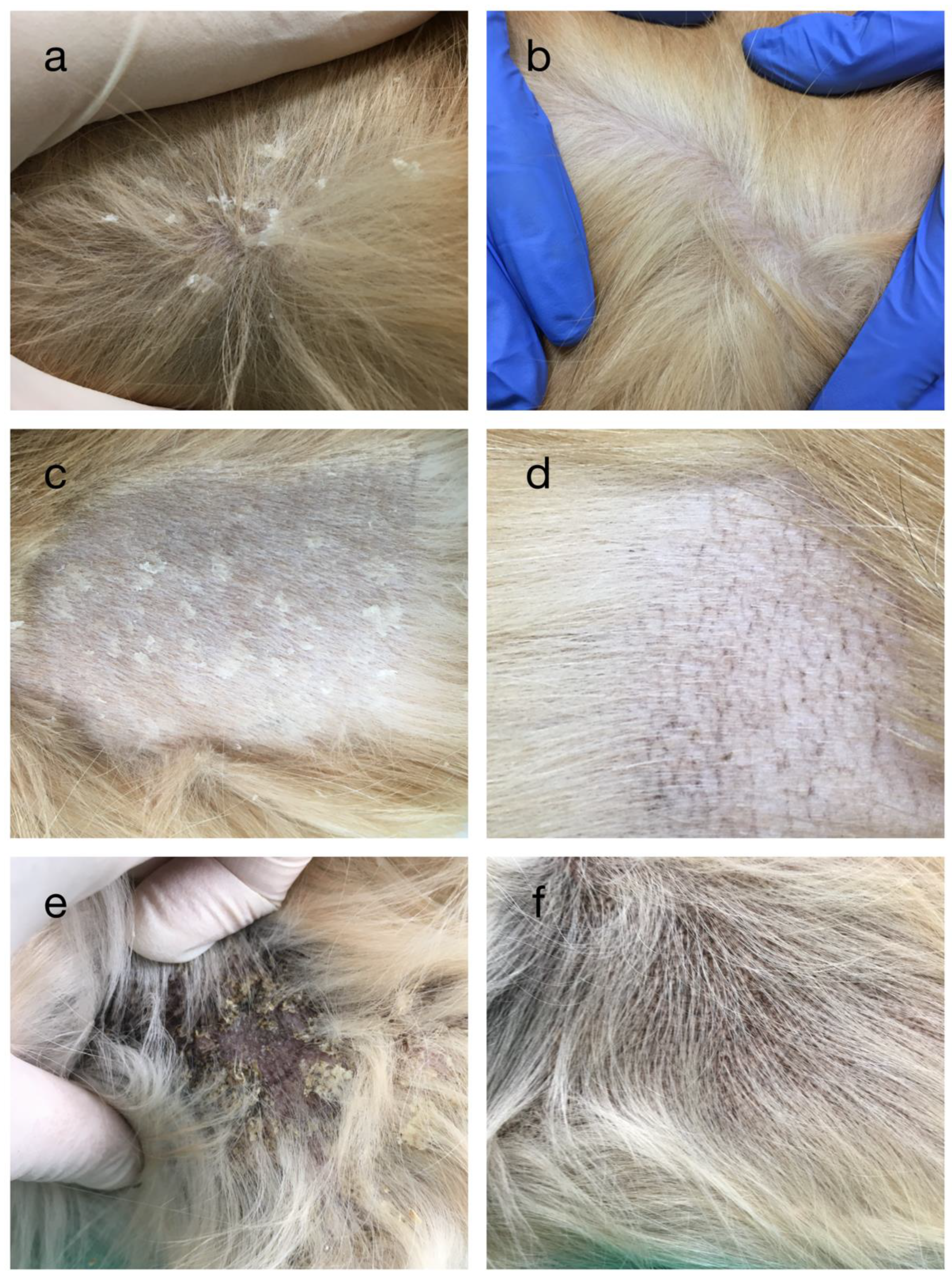

2.1. Dermatological Examination

2.2. Treatment Protocol

2.3. Blood Analysis and Schirmer Tear Test

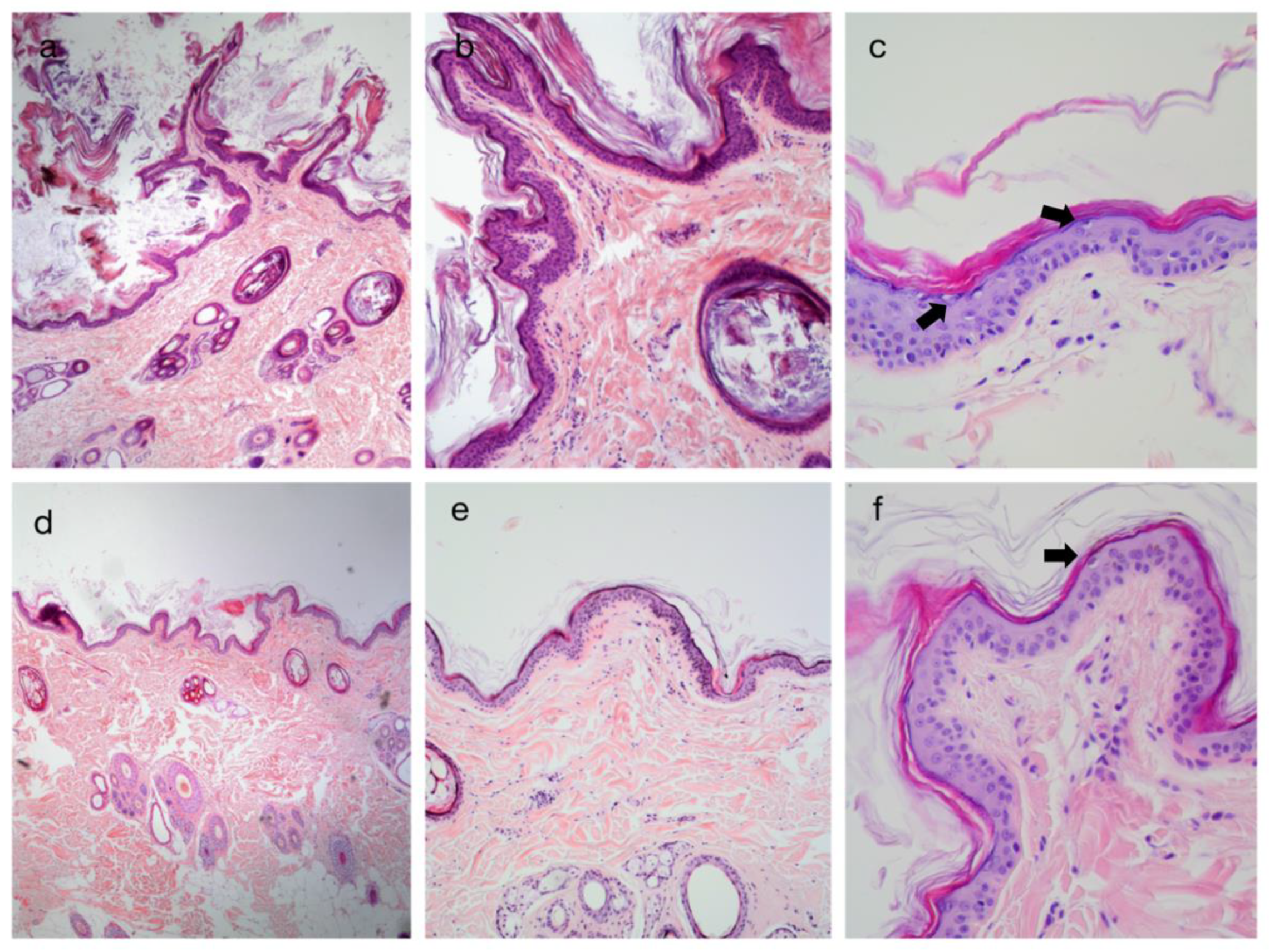

2.4. Histological Examination

2.5. Genetic Testing

3. Results

3.1. Dermatological Examination and Blood Analysis

3.2. Histopathological Findings

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Oji, V.; Tadini, G.; Akiyama, M.; Bardon, C.B.; Bodemer, C.; Bourrat, E.; Coudiere, P.; DiGiovanna, J.J.; Elias, P.; Fischer, J.; et al. Revised nomenclature and classification of inherited ichthyoses: Results of the First Ichthyosis Consensus Conference in Sorèze 2009. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2010, 63, 607–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mauldin, E.A.; Credille, K.; Dunstan, R.W.; Casal, M.L. The Clinical and Morphologic Features of Nonepidermolytic Ichthyosis in the Golden Retriever. Vet. Pathol. 2008, 45, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Guaguere, E.; Bensignor, E.; Küry, S.; Müller, A.; Herbin, L.; Fontaine, J.; Andre, C.; Degorce-Rubiales, F. Clinical, histopathological and genetic data of ichthyosis in the golden retriever: A prospective study. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2009, 50, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grall, A.; Guaguere, E.; Planchais, S.; Grond, S.; Bourrat, E.; Hausser, I.; Hitte, C.; Le Gallo, M.; Derbois, C.; Kim, G.-J.; et al. PNPLA1 mutations cause autosomal recessive congenital ichthyosis in golden retriever dogs and humans. Nat. Genet. 2012, 44, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baulande, S.; Langlois, C. Proteins sharing PNPLA domain, a new family of enzymes regulating lipid metabolism. Med. Sci. 2010, 26, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vahlquist, A.; Fischer, J.; Törmä, H. Inherited Nonsyndromic Ichthyoses: An Update on Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Treatment. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2017, 19, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loriè, E.; Gånemo, A.; Borgers, M.; Wouters, L.; Blockhuys, S.; Plassche, L.; Törmä, H.; Vahlquist, A. Expression of retinoid-regulated genes in lamellar ichthyosis vs. healthy control epidermis: Changes after oral treatment with liarozole. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2009, 89, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Puigdemont, A.; Furiani, N.; De Lucia, M.; Carrasco, I.; Ordeix, L.; Fondevila, D.; Ramió-Lluch, L.; Brazís, P. Topical polyhydroxy acid treatment for autosomal recessive congenital ichthyosis in the golden retriever: A prospective pilot study. Vet. Dermatol. 2018, 29, 323-e113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamamoto-Mochizuki, C.; Banovic, F.; Bizikova, P.; Laprais, A.; Linder, K.E.; Olivry, T. Autosomal recessive congenital ichthyosis due to PNPLA1 mutation in a golden retriever-poodle cross-bred dog and the effect of topical therapy. Vet. Dermatol. 2016, 27, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziano, L.; Vasconi, M.; Cornegliani, L. Prevalence of PNPLA1 Gene Mutation in 48 Breeding Golden Retriever Dogs. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hill, P.B.; Lau, P.; Rybnicek, J. Development of an owner-assessed scale to measure the severity of pruritus in dogs. Vet. Dermatol. 2007, 18, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, D.L. Analysis of tear uptake by the Schirmer tear test strip in the canine eye. Vet. Ophthalmol. 2005, 8, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guaguère, E.; Bensignor, E. Les ichtyoses du chien. Bulletin de l’Académie Vétérinaire de France 2007, 160, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaenglein, A.L.; Levy, M.L.; Stefanko, N.S.; Benjamin, L.T.; Bruckner, A.L.; Choate, K.; Craiglow, B.G.; DiGiovanna, J.J.; Eichenfield, L.F.; Elias, P.; et al. Consensus recommendations for the use of retinoids in ichthyosis and other disorders of cornification in children and adolescents. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2020, 38, 164–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichner, R.; Kahn, M.; Capetola, R.J.; Gendimenico, G.J.; Mezick, J.A. Effects of Topical Retinoids on Cytoskeletal Proteins: Implications for Retinoid Effects on Epidermal Differentiation. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1992, 98, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- DiGiovanna, J.J. Retinoid chemoprevention in patients at high risk for skin cancer. Med. Pediatr. Oncol. 2001, 36, 564–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draghici, C.-C.; Miulescu, R.-G.; Petca, R.-C.; Petca, A.; Dumitrașcu, M.C.; Șandru, F. Teratogenic effect of isotretinoin in both fertile females and males (Review). Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 21, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onnis, G.; Chiavérini, C.; Hickman, G.; Dreyfus, I.; Fischer, J.; Bourrat, E.; Mazereeuw-Hautier, J. Alitretinoin reduces erythema in inherited ichthyosis. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2018, 13, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Szymański, Ł.; Skopek, R.; Palusińska, M.; Schenk, T.; Stengel, S.; Lewicki, S.; Kraj, L.; Kamiński, P.; Zelent, A. Retinoic Acid and Its Derivatives in Skin. Cells 2020, 9, 2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Kaur, M.; Kaur, R.; Singh, S. Severe ectropion in lamellar ichthyosis managed medically with oral acitretin. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2018, 35, e117–e120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiGiovanna, J.J.; Mauro, T.; Milstone, L.M.; Schmuth, M.; Toro, J.R. Systemic retinoids in the management of ichthyoses and related skin types. Dermatol. Ther. 2013, 26, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ghyselinck, N.B.; Duester, G. Retinoic acid signaling pathways. Development 2019, 146, dev167502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Power, H.T.; Ihrke, P.J. Synthetic Retinoids in Veterinary Dermatology. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 1990, 20, 1525–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenner, J.; Silverberg, N.B. Skin diseases associated with atopic dermatitis. Clin. Dermatol. 2018, 36, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, S.C.; Wood, J.L.N.; Freeman, J.; Littlewood, J.D.; Hannant, D. Estimation of heritability of atopic dermatitis in Labrador and Golden Retrievers. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2004, 65, 1014–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Petak, A.; Šoštarić-Zuckermann, I.-C.; Hohšteter, M.; Lemo, N. Isotretinoin Treatment for Autosomal Recessive Congenital Ichthyosis in a Golden Retriever. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci9030097

Petak A, Šoštarić-Zuckermann I-C, Hohšteter M, Lemo N. Isotretinoin Treatment for Autosomal Recessive Congenital Ichthyosis in a Golden Retriever. Veterinary Sciences. 2022; 9(3):97. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci9030097

Chicago/Turabian StylePetak, Ana, Ivan-Conrado Šoštarić-Zuckermann, Marko Hohšteter, and Nikša Lemo. 2022. "Isotretinoin Treatment for Autosomal Recessive Congenital Ichthyosis in a Golden Retriever" Veterinary Sciences 9, no. 3: 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci9030097

APA StylePetak, A., Šoštarić-Zuckermann, I.-C., Hohšteter, M., & Lemo, N. (2022). Isotretinoin Treatment for Autosomal Recessive Congenital Ichthyosis in a Golden Retriever. Veterinary Sciences, 9(3), 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci9030097