Co-Produced Care in Veterinary Services: A Qualitative Study of UK Stakeholders’ Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Thematic Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Thematic Analysis

3.1.1. Theme One: Empathy

I think just that something that’s very precious to me is in their care and their understanding that I was feeling, that you are feeling anxious and worried and you want to know that everything is okay.[07C]

I remember her putting her arms around me and she was just really compassionate about how we were feeling.[13C]

She was lovely, I don’t know the vet’s name, it wasn’t the vet that I used to see on a regular basis for normal appointments and she was just really, really lovely.[13C]

I think that you have got to have empathy and compassion with the animal.[01P]

They also want to make sure that their pet is being cared for in the right way and they have got the best quality of care that there is, no matter what time of day. They want to see care and compassion in the situation.[09P]

I think they [clients] would be looking for a sympathetic hearing for what they want. I think they’d be looking for suitable amplification of the problems that they’re putting over, a solution to the problem that they’re presenting.[06P]

You’ve got to make them feel that their animals are important. The vet isn’t just looking at their watch and saying, “I’ve got another call to do”. The worst thing that vets can do is to say, “I’m in a hurry so I can’t be long at this”. It’s the while you’re here is the important thing and that welds the relationship between the client.[03V]

3.1.2. Theme Two: Bespoke Care

They want expertise I think initially. They want attention when they want it, ASAP of course, especially in a crisis. You can understand that. They want latest information. They want expertise and they want practicality. They want pragmatism and they want understanding of their situation. There is a bespoke element to it. Although they wouldn’t voice it as that, there is that bespoke requirement—“I need this, and I need that”. The demands are high because they perceive the veterinarian as expensive.[03V]

[In discussions with the farm vet] After we’ve had the weekly routine [visit] they’ll always come up to the house. We’ll sit down and discuss things, if there’s an issue.[12C]

It’s not unusual to spend twenty minutes, half an hour, talking to somebody. I actually quite enjoy it.[05P]

3.1.3. Theme Three: Professional Integrity

People aren’t going to trust your decision-making if they don’t think that you are a trustworthy person and that comes across in the way that you present yourself.[04V]

Because you’ve got to trust them and they’ve got to trust, I suppose, a little bit in you as well. So, it’s nice to have that but they also know when to keep it professional, and when to keep it personal as well.[02C]

If there’s a problem with a cow, and shall we say it’s what I would class as an internal problem where I can’t see any physical problems with the cow, obviously, I trust that the vet is able to make a good diagnosis.[02C]

Well because you are paying for that professional service and their opinions and that I’m entrusting them with the care of my animals.[13C]

3.1.4. Theme Four: Value for Money

At the moment, veterinarians haven’t been very good at charging for time, they’ve subsidized it by sales and medicine. That’s tempered the whole best way forward. The best way forward in my view is for veterinarians to sell their time and not much else.[03V]

The vast majority of farmers have a high level of expectation of the vets. They’ve an expectation of good service, expectation of reasonable prices, but they know that they’re always going to get a reasonable sized total bill at the end of the month. That’s what they expect from vets. But they expect the highest standards and that’s okay as long as they can see the value.[04V]

Cost plays an element, but what we find is there are competitors in our area who would sell some wormers cheaper than us. But having spent an awful lot of time training people, our SQPs [Suitably Qualified Persons/Animal Medicines Advisor], and the relationship we’ve built with clients, it’s not always about the price anymore.[04V]

For example, paying a full call out for them to come and do vaccinations, which they can do standing on their head. It doesn’t really take a lot of ability. But I think largely, considering what they’re doing, which is highly technical, I do think it is good value for money, knowing what similar things cost in medicine.[07C]

3.1.5. Theme Five: Confident Relationships

You have to actually communicate with the owner in every possible available way and develop that ability.[04V]

Communication is one of the key things that they [clients] definitely expect and a follow-up as well. They are making sure that not only are they making that initial contact with the owner about something but the follow-up after that.[09P]

Clients will be expecting it [involvement], and clients will be driving that they have that for their animal.[10P]

Will they [veterinarians] communicate with me in a professional manner, but also not treating me like I don’t know anything at all?[07C]

I have to say we’re very lucky with the people that we work with. They do challenge you. We possibly hopefully challenge them a little bit. We bounce ideas off each other. As I say they’ll often have meetings with our nutritionist, with the vet, and they’ll all sit down every couple of months together… It’s nice if they come out and give you ideas and suggestions, and challenge your thinking as well…[12C]

I don’t think a lot of veterinarians value the opinion of the owner, despite the fact that some owners are very experienced with their own horse or with a number of horses.[07C]

Because I think doctors are now taught to communicate. They do loads of role-play, especially if they’re going to be a GP [General Practitioner Doctor], and realise, “Actually, I can communicate with these people, and it should be a two-way street. But I think people need to be taught to communicate. If you’re a four A* student, who has studied really hard, you may not have the social skills, the interpersonal skills. You need to learn those if you don’t have them naturally, which some people do.[07C]

I’m looking for them [allied practitioners] to be able to identify—obviously they have a conversation with me first about what my thoughts are. I think it’s important that I feel involved.[08C]

She looked at how he [the horse] moved. She did a really in-depth assessment when she first met the horse, and then treated it very thoroughly, gave me exercises that I could do… I was very involved. I always want to feel that I can do my bit as well, and I can’t believe that somehow something just needs treating in three months, six months, twelve months. There’s got to be some kind of self-care in the meantime.[07C]

So, it’s more listening to what the farmer wants, based on the herd size, and how they want to run things. It’s not just what they [the vet] think. It’s the involvement of the farmer and what he wants with his animals.[12C]

3.1.6. Theme Six: Accessibility

It is problematic. Just the thought that you can’t just get the vet when you want them is problematic to me, and booking so far in advance.[02C]

It was two miles from where I lived, could always get an appointment straight away. I was always very pleased with the care that I got for all of my animals.[13C]

Enquiries on our advice line are actually dropping, and enquiries through social media are going through the roof. She’ll get a tweet at ten o ‘clock at night and answer it.[05P]

4. Discussion

5. Further Work

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Waters, A. What will the future bring? Vet. Rec. 2017, 180, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widmar, N.O.; Bir, C.; Slipchenko, N.; Wolf, C.; Hansen, C.; Ouedraogo, F. Online Procurement of Pet Supplies and Willingness to Pay for Veterinary Telemedicine. Prev. Vet. Med. 2020, 181, 105073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roca, R.Y.; McCarthy, R.J. Impact of Telemedicine on the Traditional Veterinarian-Client-Patient Relationship. Top. Companion Anim. Med. 2019, 37, 100359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mintel. Pet Food and Pet Care Retailing-UK. 2018. Available online: https://reports.mintel.com/display/908814/ (accessed on 26 May 2020).

- BVA. Workforce Report. Available online: https://www.bva.co.uk/media/2990/motivation-satisfaction-and-retention-bva-workforce-report-nov-2018-1.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2020).

- Lowe, P. Unlocking Potential: A Report on Veterinary Expertise in Food Animal Production; Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs: London, UK, 2009.

- RCVS (Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons). RCVS FACTS. Facts and Figures from the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons; RCVS: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wedderburn, P. Ten Ways the Veterinary Profession is Changing. Available online: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/pets/news-features/ten-ways-veterinary-profession-changing/ (accessed on 1 July 2020).

- Kogan, L.R.; Goldwaser, G.; Stewart, S.M.; Schoenfeld-Tacher, R. Sources and frequency of use of pet health information and level of confidence in information accuracy, as reported by owners visiting small animal veterinary practices. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2008, 232, 1536–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogan, L.; Oxley, J.A.; Hellyer, P.; Schoenfeld-Tacher, R. United Kingdom veterinarians’ perceptions of clients’ internet use and the perceived impact on the client–vet relationship. Front. Vet. Sci. 2017, 4, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.R. The dimensions of pet-owner loyalty and the relationship with communication, trust, commitment and perceived value. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmins, R. The contribution of animals to human well-being: A veterinary family practice perspective. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2008, 35, 540–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, E.; Son, H. The Human–Companion animal bond: How humans benefit. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2009, 39, 293–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, D.L. The state of research on human–animal relations: Implications for human health. Anthrozoös 2019, 32, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, E.; Graham, R.; McManus, P. ‘No one has even seen smelt or sensed a social licence’: Animal geographies and social licence to operate. Geoforum 2018, 96, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heleski, C.; Stowe, C.J.; Fiedler, J.; Peterson, M.L.; Brady, C.; Wickens, C.; MacLeod, J.N. Thoroughbred Racehorse Welfare through the Lens of ‘Social License to Operate—With an Emphasis on a US Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, M.; Hemsworth, L.M.; Hemsworth, P.H.; Coleman, G.J. The Impact of a Negative Media Event on Public Attitudes Towards Animal Welfare in the Red Meat Industry. Animals 2020, 10, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coleman, G. Consumer and societal expectations for sheep products. Adv. Sheep Welf. 2017, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vet Futures. Taking Charge of Our Future: A Vision for the Veterinary Profession for 2030; Vet Futures: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, J.; Adams, C.L.; Bonnett, B.N. What can veterinarians learn from studies of physician-patient communication about veterinary-client-patient communication? J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2004, 224, 676–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, J.; Adams, C.; Bonnett, B.; Larson, S. Veterinarian-client-patient communication during wellness appointments versus appointments related to a health problem in companion animal practice. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2008, 233, 1576–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, J.; Adams, C.; Bonnett, B.N.; Larson, S.; Roter, D.L. Veterinarian satisfaction with companion animal visits. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2012, 240, 832–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grand, J.A.; Lloyd, J.W.; IIgen, D.R.; Abood, S.; Sonea, I.M. A measure of and predictors for veterinarian trust developed with veterinary students in a simulated companion animal practice. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2013, 242, 322–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomans, J.B.; van Weeren, P.R.; Vaarkamp, H.; Stolk, P.T.; Barneveld, A. Quality of equine veterinary care: Where can it go wrong? A conceptual framework for the quality of equine healthcare, based on court cases against equine practitioners in The Netherlands. Equine Vet. Educ. 2008, 20, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Crossing the great divide: Coproduction, synergy, and development. World Dev. 1996, 24, 1073–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotze, T.G.; Du Plessis, P.J. Students as “co-producers” of education: A proposed model of student socialisation and participation at tertiary institutions. Qual. Assur. Educ. 2003, 11, 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovaird, T.; Stoker, G.; Jones, T.; Loeffler, E.; Pinilla Roncancio, M. Activating collective co-production of public services: Influencing citizens to participate in complex governance mechanisms in the UK. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2016, 82, 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pestoff, V.; Brandsen, T.; Verschuere, B. (Eds.) New Public Governance, the Third Sector, and co-Production; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Malby, B. NHS Reform: A Radical Approach through co-Production? The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/healthcare-network/2012/mar/21/nhs-reform-radical-approach-co-production (accessed on 20 November 2019).

- Martin, G.P.; Finn, R. Patients as team members: Opportunities, challenges and paradoxes of including patients in multi-professional healthcare teams. Sociol. Health Illn. 2011, 33, 1050–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert., G.; Cornwell, J.; Lockock, L. Patients and staff as co-designers of healthcare services. BMJ 2015, 350, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, D.; Harris, M. The challenge of co-production. Lond. New Econ. Found. 2009, 56, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Pralahad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. The Future of Competition: Co-Creating Unique Value with Customers; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Vogus, T.J.; McCelland, L.E. When the customer is the patient: Lessons from healthcare research on patient satisfaction and service quality ratings. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2016, 26, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathert, C.; Wyrwich, M.D.; Bohren, S.A. Patient-centred care and outcomes. A systematic review of the literature. Med. Care Res. Rev. 2013, 70, 351–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendall-Lyon, D.; Powers, T.L. The impact of structure and process attributes on satisfaction and behavioural intensions. J. Serv. Mark. 2004, 18, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiedke, C.C. What do we really know about patient satisfaction? Fam. Pract. Manag. 2007, 14, 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Vogus, T.J.; McClelland, L.E. Actions, style and practices: How leaders ensure compassionate care delivery. BMJ Lead. 2020, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, B.; Sim, J.; Kingstone, T.; Baker, S.; Waterfield, J.; Bartlam, B.; Burroughs, H.; Clare Jinks, C. Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual. Quant. 2018, 52, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etikan, I.; Musa, S.A.; Alkassim, R.S. Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2016, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong., A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Routledge: Chicago, IL, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Urquhart, C. Grounded Theory for Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lusch, R.F.; Vargo, S.L. Service-dominant logic: A necessary step. Eur. J. Mark. 2011, 45, 1298–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Service-dominant logic: Continuing the evolution. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2008, 36, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grönroos, C. Value co-creation in service logic: A critical analysis. Mark. Theory 2008, 11, 279–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharti, K.; Agrawal, R.; Sharma, V. Literature review and proposed conceptual framework. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2015, 57, 571–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coe, J.B.; Adams, C.L.; Bonnett, B.N. A focus group study of veterinarians’ and pet owners’ perceptions of veterinarian-client communication in companion animal practice. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2008, 233, 1072–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, F. Idealistic and pragmatic versions of the discourse of partnership. Organ. Stud. 2005, 26, 1169–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, S.; Swan, J. Trust and inter-organizational networking. Hum. Relat. 2000, 53, 1287–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.; Dugan, E.; Zheng, B.; Mishra, A.K. Trust in physicians and medical institutions: What is it, can it be measured, and does it matter? Milbank Q. 2001, 79, 613–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grönroos, C. Creating a relationship dialogue: Communication, interaction and value. Mark. Rev. 2000, 1, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusch, R.F.; Vargo, S.L. Service-dominant logic: Reactions, reflections and refinements. Mark. Theory 2006, 6, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leppiman, A.; Same, S. Experience marketing; conceptual insights and the difference from experiential marketing. Reg. Bus. Socio-Econ. Dev. 2011, 5, 240–258. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, J.; Langley, J.; Wolstenholme, D.; Hampshaw, S. Seeing” the difference: The importance of visibility and action as a mark of” authenticity” in co-production: Comment on” collaboration and co-production of knowledge in healthcare: Opportunities and challenges. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2017, 6, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derksen, F.; Bensing, J.; Lagro-Janssen, A. Effectiveness of empathy in general practice: A systematic review. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2013, 63, e76–e84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpern, J. What is clinical empathy? J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2003, 18, 670–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjortdahl, P.; Laerum, E. Continuity of care in general practice: Effect on patient satisfaction. Br. Med. J. 1992, 304, 1287–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safran, D.G.; Montgomery, J.E.; Chang, H.; Murphy, J.; Rogers, W.H. Switching doctors; predictors of voluntary disenrollment from a primary physician’s practice. J. Fam. Pract. 2001, 50, 130–136. [Google Scholar]

- Cabana, M.D.; Jee, S.H. Does continuity of care improve patient outcomes? J. Fam. Pract. 2004, 53, 974–980. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, S.; Renedo, A.; Marston, C. ‘Slow co-production’ for deeper patient involvement in health care. J. Health Des. 2018, 3, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipe, A.; Renedo, A.; Marston, C. The co-production of what? Knowledge, values, and social relations in health care. PLoS Biol. 2017, 15, e2001403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunston, R.; Lee, A.; Boud, D.; Brodie, P.; Chiarella, M. Co-production and health system reform–from re-imagining to re-making. Aust. J. Public Adm. 2009, 68, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Global Strategy on People-Centred and Integrated Health Services: Interim Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, L. Bridging the divide between theory and practice: Taking a co-productive approach to vet-farmer relationships. Food Ethics 2018, 1, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bard, A.M.; Main, D.C.J.; Haase, A.M.; Whay, H.R.; Roe, E.; Reyher, K.K. The future of veterinary communication: Partnership or persuasion? A qualitative investigation of veterinary communication in the pursuit of client behaviour change. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Code | Classification | Gender | Age (Approximate) | Occupation | Additional Information |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01P | Allied Practitioners | F | 60 | Musculoskeletal professional | Equine specialist |

| 02C | Client | M | 35 | Farmer | Extensive mixed livestock |

| 03V | Veterinarian | M | 68 | Farm and mixed practice | Industry knowledge transfer |

| 04V | Veterinarian | M | 50 | Farm | Referral mixed practice |

| 05P | Allied Practitioners | F | 40 | Senior nutritionist | Equine specialist |

| 06P | Allied Practitioners | M | 70 | Veterinary pharmacist | Companion animal specialist |

| 07C | Client | F | 50 | Medical writer | Dog and horse owner |

| 08C | Client | F | 30 | Dog trainer | Dog and horse owner |

| 09P | Allied Practitioners | F | 20 | Veterinary nurse | Mixed practice |

| 10P | Allied Practitioners | M | 30 | Musculoskeletal practitioner | Equine specialist |

| 11V | Veterinarian | F | 30 | Companion animal specialist | Charity companion animal |

| 12C | Client | F | 30 | Farmer | Intensive dairy |

| 13C | Client | F | 50 | Administrator | Dog owner |

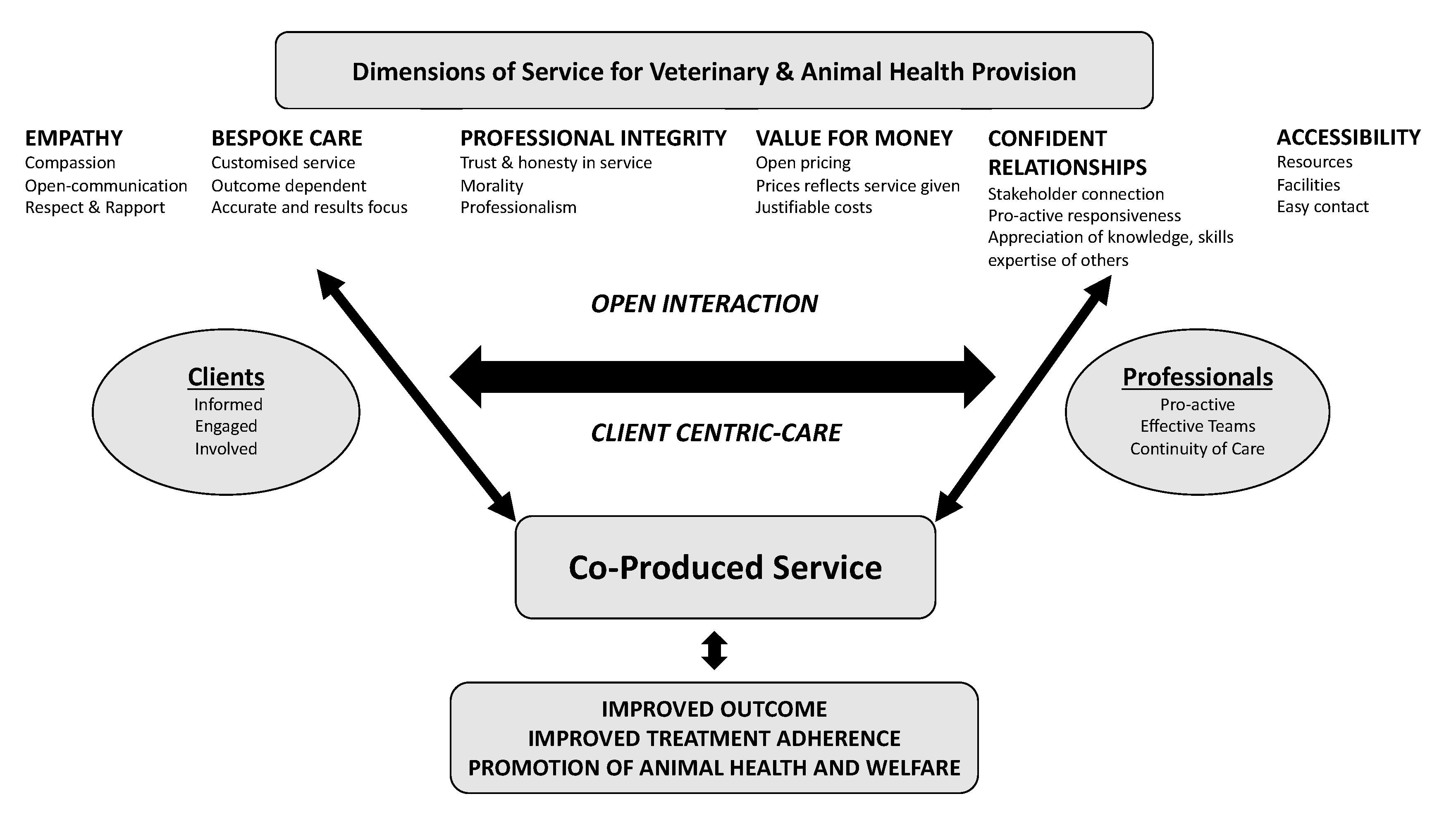

| Theme | Definition |

|---|---|

| Empathy | Compassion and thoughtfulness through a clearly communicated service. Caring provision, with due regard for clients’ needs and animal health and welfare. |

| Bespoke Care | Custom tailored, dependable service which is accurate and a results-focused provision. |

| Professional Integrity | Trust, honesty and morality of service delivery. Strong themes of professionalism. |

| Value for Money | Willingness to provide comprehensive service within a justifiable pricing strategy. Price paid reflects the service given. |

| Confident Relationships | Professionals’ connection with the client, connection with other professionals, and pro-active responsiveness to the wider knowledge, skills, and expertise of others. Preparedness to undertake two-way open communication with an active client, demonstrative of respect and rapport. |

| Accessibility | Geographical proximity of up-to-date resources and facilities, accessibility of professionals (physical and communicative), and ease of contact. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pyatt, A.Z.; Walley, K.; Wright, G.H.; Bleach, E.C.L. Co-Produced Care in Veterinary Services: A Qualitative Study of UK Stakeholders’ Perspectives. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci7040149

Pyatt AZ, Walley K, Wright GH, Bleach ECL. Co-Produced Care in Veterinary Services: A Qualitative Study of UK Stakeholders’ Perspectives. Veterinary Sciences. 2020; 7(4):149. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci7040149

Chicago/Turabian StylePyatt, Alison Z., Keith Walley, Gillian H. Wright, and Emma C. L. Bleach. 2020. "Co-Produced Care in Veterinary Services: A Qualitative Study of UK Stakeholders’ Perspectives" Veterinary Sciences 7, no. 4: 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci7040149

APA StylePyatt, A. Z., Walley, K., Wright, G. H., & Bleach, E. C. L. (2020). Co-Produced Care in Veterinary Services: A Qualitative Study of UK Stakeholders’ Perspectives. Veterinary Sciences, 7(4), 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci7040149