Capacity Allocation of Game Tickets Using Dynamic Pricing

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Model

3. Results

3.1. Data Cleaning

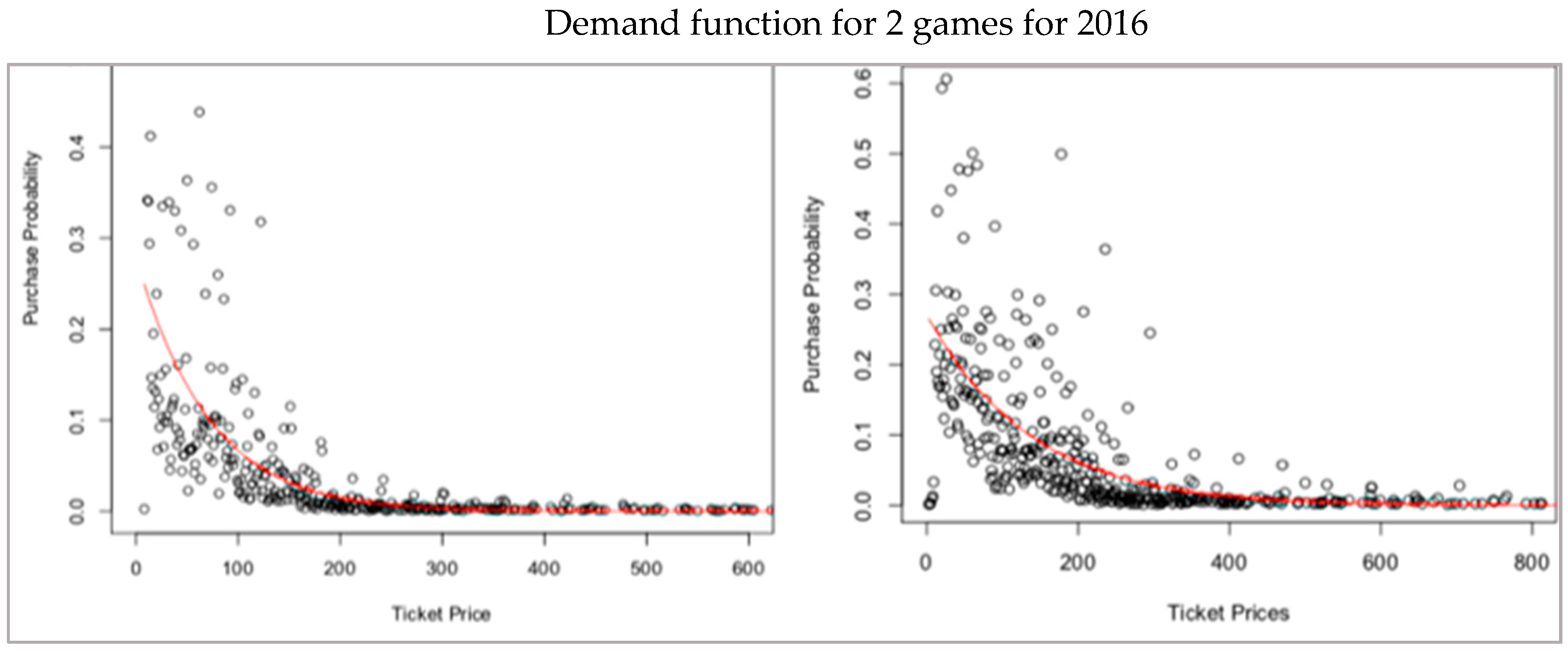

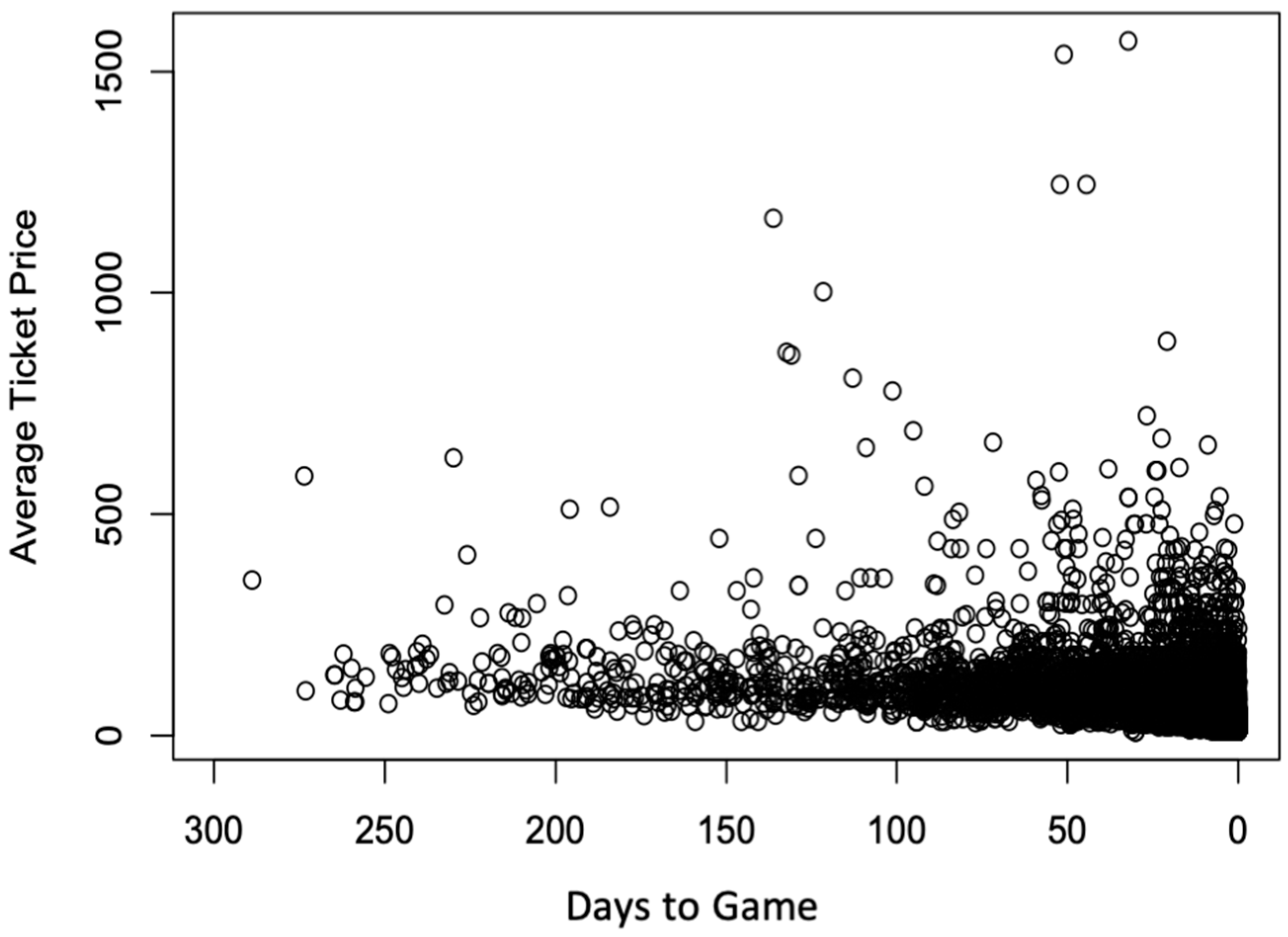

3.2. Optimal Fixed Price and Dynamic Price

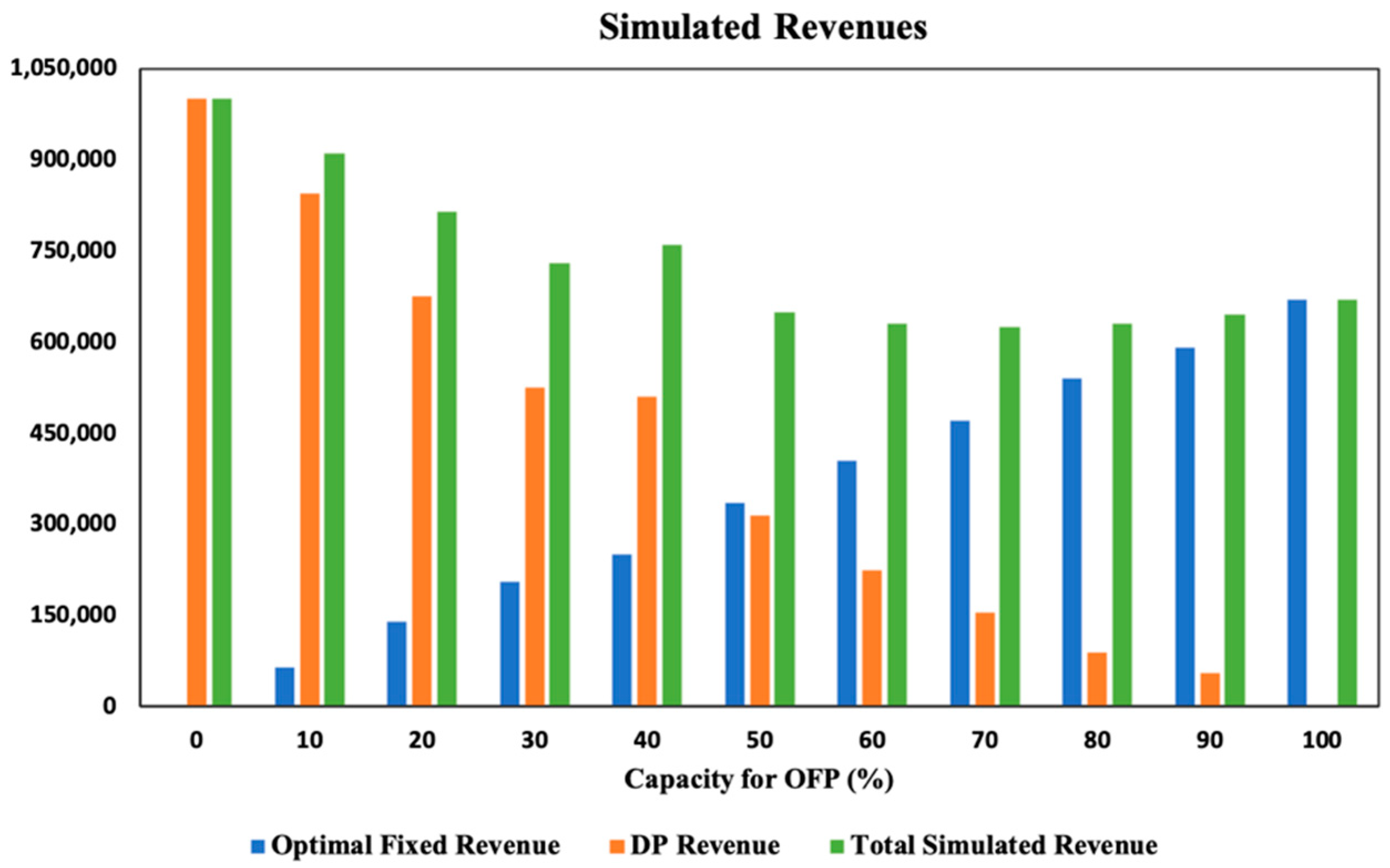

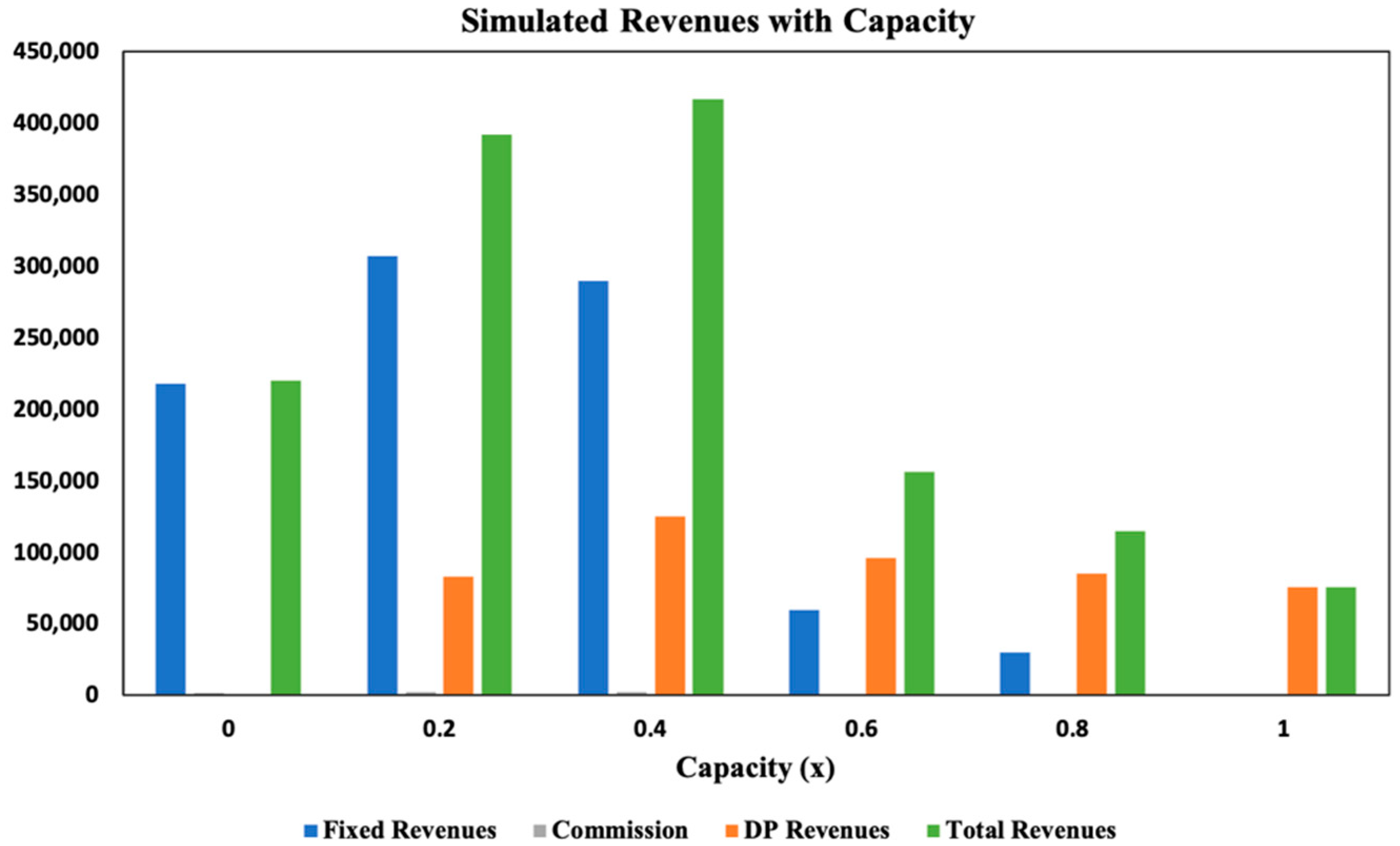

3.3. Optimal Capacity Allocation

- .

4. Conclusions and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McAfee, A.; Brynjolfsson, E. Big Data: The Management Revolution. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2012, 90, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lovelace, R. The Data Revolution: Big Data, Open Data, Data Infrastructures and Their Consequences, by Rob Kitchen; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Alfredo, C.; Song, Y., II; Karen, C.D. Analytics over large-scale multidimensional data: The big data revolution. In Proceedings of the ACM 14th international workshop on Data Warehousing and OLAP (DOLAP ‘11); ACM: New York, NY, USA; pp. 101–104. [CrossRef]

- Drayer, J.; Shapiro, S.L.; Lee, S. Dynamic ticket pricing in sports: An agenda for research and practice. Sports Mark. Q. 2012, 21, 184–194. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns, J.A.; Jennett, N.; Sloane, P.J. The economics of professional team sports: A survey of theory and evidence. J. Econ. Stud. 1986, 13, 3–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borland, J.; MacDonald, R. Demand for sports. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2003, 19, 478–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downward, P.; Dawson, A. The Economics of Professional Team Sports; Routledge: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Coates, D.; Humphreys, B.R. Ticket prices, concessions and attendance at professional sporting events. Int. J. Sports Financ. 2007, 2, 161–170. [Google Scholar]

- Krautmann, A.C.; Berri, D.J. Can we find it at the concessions? Understanding price elasticity in professional sports. J. Sports Econ. 2007, 8, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.M.; Potter, J.M.; Sanders, S. Inelastic sports ticket pricing, marginal win revenue, and firm pricing strategy: A behavioral pricing model. Manag. Financ. 2016, 42, 922–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, G.; van Ryzin, G.J. Optimal dynamic pricing of inventories with stochastic demand over finite horizons. Manag. Sci. 1994, 40, 999–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, G.; van Ryzin, G.J. A multiproduct dynamic pricing problem and its applications to network yield management. Oper. Res. 1997, 45, 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.Y. Dynamic pricing with real-time demand learning. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2006, 174, 522–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Robinson, D.R. A Dynamic Programming Solution to Cost-Time Tradeoff for CPM. Manag. Sci. 1975, 22, 139–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berovic, D.P.; Vinter, R.B. The application of Dynamic Programming to Optimal Inventory Control. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2004, 49, 676–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, H.A. Dynamic Programming Under Uncertainty with a Quadratic Criterion Function. Econommetrica 1956, 24, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.C.; Hersh, M. A Model for Dynamic Airline Seat Inventory Control with Multiple Seat Bookings. Transp. Sci. 1993, 27, 209–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, W.; Shang, J.; Wang, F. Pricing determinants in the hotel industry: Quantile regression analysis. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 29, 378–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrate, G.; Fraquelli, G.; Viglia, G. Dynamic pricing strategies: Evidence from European hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Belobaba, P.P. Airline yield management: An overview of seat inventory control. Transp. Sci. 1987, 21, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belobaba, P.P. Application of a probabilistic decision model to airline seat inventory control. Oper. Res. 1989, 37, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Mattila, A.S. Hotel revenue management and its impact on customer fairness perceptions. J. Revenue Pricing Manag. 2004, 2, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Mattila, A.S. Impact of information on customer fairness perceptions of hotel revenue management. Cornell Hotel Restaur. Adm. Q. 2005, 46, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biller, S.; Chan, L.M.A.; Simchi-Levi, D.; Swann, J. Dynamic pricing and the directto-customer model in the automotive industry. Electron. Commer. Res. 2005, 5, 309–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, L.; Shen, Z.; Simchi-Levi, D.; Swann, J. Coordination of Pricing and Inventory Decisions: A Survey and Classification. In Handbook of Quantitative Supply Chain Analysis; Simchi-Levi, D., Ed.; Kluwer Academic: Boston, MA, USA, 2004; pp. 335–392, ISBN-10: 1402079524. [Google Scholar]

- Kannan, P.; Kopalle, P. Dynamic pricing on the internet: Importance and implications for consumer behavior. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2001, 5, 63–83. [Google Scholar]

- Leloup, B.; Deveaux, L. Dynamic pricing on the internet: Theory and simulations. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2001, 1, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, Y.; McGill, J.; Nediak, M. Dynamic pricing in the presence of strategic consumers and oligopolistic competition. Manag. Sci. 2009, 55, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maglaras, C.; Meissner, J. Dynamic pricing strategies for multiproduct revenue management problems. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2006, 8, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiss, M.; Kirstein, R. Optimal ticket pricing in professional sports: A social identity approach. Econ. Bull. 2014, 34, 2138–2150. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitropoulos, P.; Alexopoulos, P. Attendance, revenues, profits and the on-field performance of the Greek football clubs. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 2014, 2, 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Bird, P.J. The demand for league football. Appl. Econ. 1982, 14, 637–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson, S.M.; Goddard, J.A. The demand for standing and seated viewing accommodation in the English Football League. Appl. Econ. 1992, 24, 1155–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeds, M.A.; Sakata, S. Take me out to the Yakyushiai: Determinants of attendance at Nippon professional baseball games. J. Sports Econ. 2012, 13, 34–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, N.M. Japanese professional soccer attendance and the effects of regions, competitive balance and rival franchises. Int. J. Sport Financ. 2012, 7, 309–323. [Google Scholar]

- Burger, J.D.; Walters, S.J.K. Market Size, Pay and Performance. A general model application to Major League Baseball. J. Sports Econ. 2003, 4, 108–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinnuck, M.; Potter, B. Impact of on-field football success on the off-field financial performance of AFL football clubs. Account. Financ. 2006, 46, 499–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berri, D.J.; Schmidt, M.B. On the road with the National Basketball Association’s superstar externality. J. Sports Econ. 2006, 7, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausman, J.A.; Leonard, G.K. Superstars in the National Basketball Association: Economic value and policy. J. Labor Econ. 1997, 15, 586–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirabile, M.P. The determinants of attendance at neutral site college football games. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2015, 36, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clapp, C.M.; Hakes, J.K. How long a honeymoon? The Effect of new stadiums on attendance in Major League Baseball. J. Sports Econ. 2005, 6, 237–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leadley, J.C.; Zygmont, Z.X. When is the honeymoon over? Major League Baseball attendance 1970–2000. J. Sport Manag. 2005, 19, 278–299. [Google Scholar]

- Kimes, S.E. The basics of yield management. Cornell Hotel Restaur. Adm. Q. 1989, 30, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drayer, J.; Shapiro, S.L. Value determination in the secondary ticket market: A quantitative analysis of the NFL playoffs. Sports Mark. Q. 2009, 18, 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Moe, W.W.; Fader, P.S.; Kahn, B. Buying tickets: Capturing the dynamic factors that drive consumer purchase decision for sporting events. In Proceedings of the MIT Sloan Sports Analytics Conference, Boston, MA, USA, 4–5 March 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Y.; Duenas, I.; Shahin, O. Sports event revenue management with consumer resale. In Proceedings of the MIT Sloan Sports Analytics Conference, Boston, MA, USA, 2–3 March 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Phumchusri, N.; Swann, J.L. Dynamic pricing with updated demand for the sports and entertainment ticket industry. J. Comput. Sci. 2014, 10, 2240–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemper, C.; Breuer, C. Dynamic ticket pricing and the impact of time-an analysis of price paths of the English soccer club Derby County. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2016, 16, 233–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.J.; Fader, P.S.; Veer Raghavan, S. Designing and evaluating dynamic pricing policies for major league baseball tickets. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2019, 21, 121–138. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, R.; Weinbach, A.P. Determinants of dynamic pricing premiums in Major League Baseball. Sports Mark. Q. 2013, 22, 152–165. [Google Scholar]

- Drayer, J.; Rascher, D.A.; McEvoy, C. An examination of underlying consumer demand and sports pricing using secondary market data. Sports Manag. Rev. 2012, 15, 448–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, R. The demand for English league football, a club-level analysis. Appl. Econ. 1996, 28, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, J.; Rodriguez, P. The determinants of football match attendance revisited: Empirical evidence from the Spanish football league. J. Sport Econ. 2002, 3, 18–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, D.K.; Miller, A.A. Revenue Management for the Hospitality; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dutta, A. Capacity Allocation of Game Tickets Using Dynamic Pricing. Data 2019, 4, 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/data4040141

Dutta A. Capacity Allocation of Game Tickets Using Dynamic Pricing. Data. 2019; 4(4):141. https://doi.org/10.3390/data4040141

Chicago/Turabian StyleDutta, Aniruddha. 2019. "Capacity Allocation of Game Tickets Using Dynamic Pricing" Data 4, no. 4: 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/data4040141

APA StyleDutta, A. (2019). Capacity Allocation of Game Tickets Using Dynamic Pricing. Data, 4(4), 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/data4040141