Minerality in Wine: Towards the Reality behind the Myths

Abstract

1. General Introduction

2. Conceptual and Linguistic Aspects of Perceived Minerality in Wine

2.1. Definition Tasks

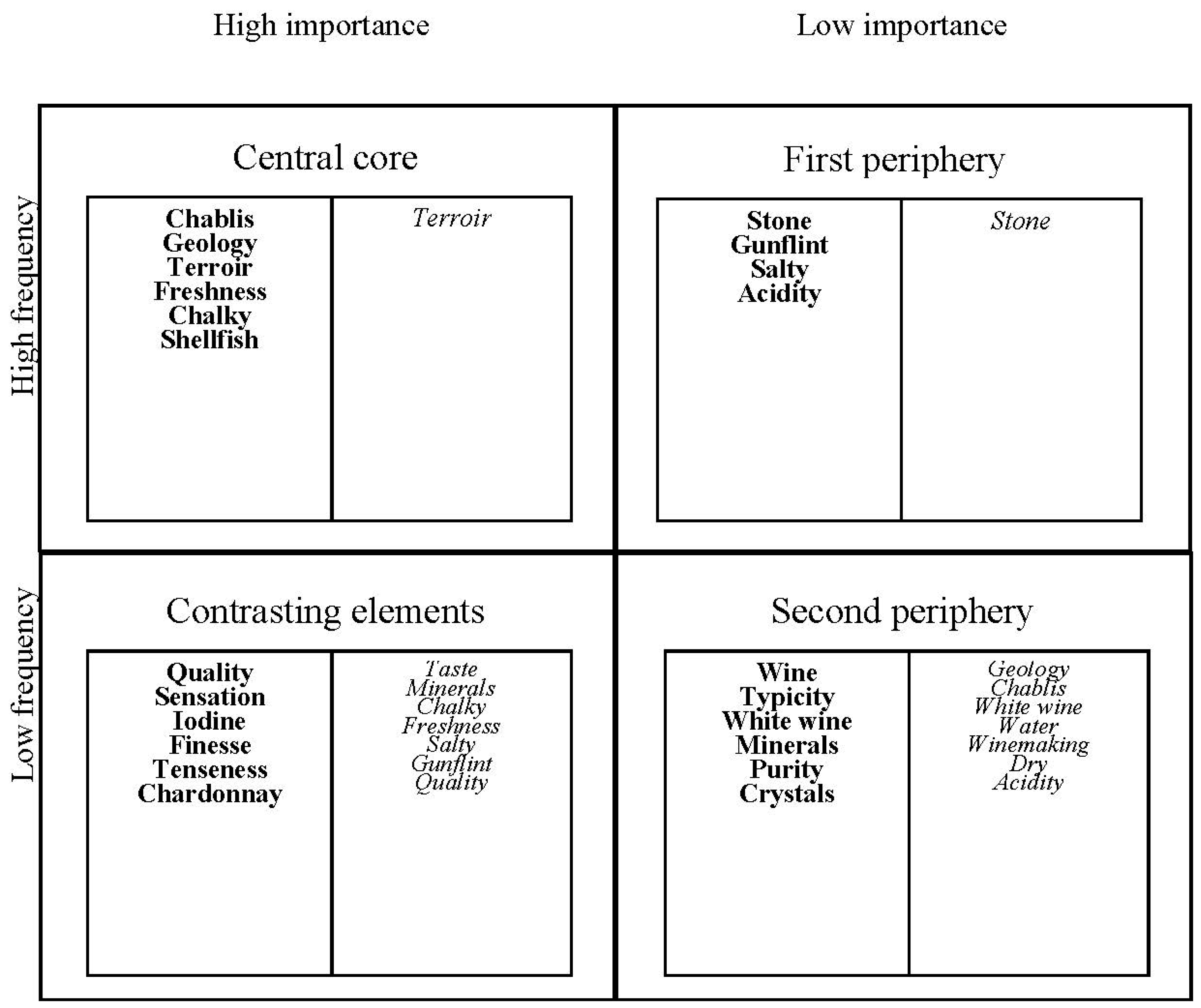

2.2. Social and/or Cerebral Representation Methodology

2.3. Synthesis and Summary

3. Geological Considerations

3.1. The Geological Mineral: Nutrient Mineral Confusion

3.2. Mineral Nutrients in the Vine

3.3. Mineral Nutrients in Wine

3.4. Rocks and Minerals Have No Flavour

3.5. Geological Terms as Metaphors

4. Sensory Characteristics of Minerality in Wine

4.1. Empirical Investigations

4.2. Synthesis and Summary

5. Associated Chemical Compounds

5.1. Investigations of Compounds and Flavours Assumed Related to Minerality

5.2. Studies Specifically Investigating Physico-Chemical Drivers of Perceived Minerality

5.3. Summary and Conclusions

5.3.1. Acidity

5.3.2. Reductive Phenomena and SO2

5.3.3. Compounds Producing/Stony/Smoky Notes

5.3.4. Compounds Producing Saltiness

5.3.5. Absence of Fruitiness and/or Wine Flavour

6. Overall Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Van Casteren, C. Un terme très tendence. In Proceedings of the Lallemand tour ‘Les Minéraux et le vin’, Nîmes/Mâcon/Chinon/Bordeaux, France, 17–20 January 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ballester, J.; Mihnea, M.; Peyron, D.; Valentin, D. Exploring minerality of Burgundy Chardonnay wines: A sensory approach with wine experts and trained panellists. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2013, 19, 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Fur, Y.; Gautier, L. De la minéralité dans les rosés? Revue Française d’Oenologie 2013, 260, 40–43. [Google Scholar]

- Deneulin, P.; Le Bras, G.; Le Fur, Y.; Gautier, L.; Bavaud, F. La minéralité des vins: Exploitation de sémantique cognitive d’une étude consommateurs. La Revue des Œnologues 2014, 153, 56–58. [Google Scholar]

- Deneulin, P.; Bavaud, F. Analyses of open-ended questions by renormalized associativities and textual networks: A study of perception of minerality in wine. Food Qual. Prefer. 2016, 47, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deneulin, P.; Le Fur, Y.; Bavaud, F. Study of the polysemic term of minerality in wine: Segmentation of consumers based on their textual responses to an open-ended survey. Food Res. Int. 2016, 90, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, H.; Ballester, J.; Saenz-Navajas, M.P.; Valentin, D. Structural approach of social representation: Application to the concept of wine minerality in experts and consumers. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 46, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jodelet, D. Les Representations Sociales; Presses universitaires de France: Paris, France, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Abric, J.C. Jeux, Conflits et Representations Sociales. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Provence, Marseille, France, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Vergès, P. L’evocation de l’argent: Une méthode pour la définition du noyau central d’une représentation. Bull. Psychol. 1992, 45, 203–209. [Google Scholar]

- Lo Monaco, G.; Lheureux, F. Représentations sociales: Théorie du noyau central et méthodes d’étude. Revue Electronique de Psychologie Sociale 2007, 1, 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Maltman, A.J. Minerality in wine: A geological perspective. J. Wine Res. 2013, 24, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiner, P. Mycorrhyzas and Mineral Acquisition in Grapevines. In Proceedings of the Soil Environment and Vine Mineral Nutrition Symposium; Christensen, P., Smart, D.R., Eds.; ASEV: Davis, CA, USA, 2005; pp. 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Velde, B.; Meunier, A. The Origin of Clay Minerals in Soils and Weathered Rocks; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fageria, N.K.; Baligar, V.C.; Jones, C.A. Growth and Mineral Nutrition of Field Crops, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, M. The Science of Grapevines: Anatomy and Physiology; Academic Press: Burlington, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Savvas, D. Hydroponics: A modern technology supporting the application of integrated crop management in greenhouse. Food Agric. Environ. 2003, 1, 80–86. [Google Scholar]

- Castiñera Gómez Mdel, M.; Brandt, R.; Jakubowski, N.; Anderson, J.T. Changes of the metal composition in German white wines through the winemaking process. A study of 63 elements by inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 2953–2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pohl, P. What do metals tell us about wine? TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2007, 26, 941–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatár, E.; Mihucz, V.G.; Virág, I.; Rácz, L.; Záray, G. Effect of four bentonite samples on the rare earth element concentrations of selected Hungarian wine samples. Microchem. J. 2007, 85, 132–135. [Google Scholar]

- Aceto, M.; Bonello, F.; Musso, D.; Tsolakis, C.; Cassino, C.; Osella, D. Wine traceability with rare earth elements. Beverages 2018, 4, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkes, E.; Day, M.; Herderich, M.; Johnson, D. In vino veritas—Investigating technologies to fight wine fraud. Wine Vitic. J. 2016, 31, 36–38. [Google Scholar]

- Hommerberg, C.; Paradis, C. Constructing credibility through representations in the discourse of wine: Evidentiality, temporality and epistemic control. In Subjectivity and Epistemicity. Corpus, Discourse, and Literary Approaches to Stance; Glynn, D., Sjölin, M., Eds.; Lund University Press: Lund, Sweden, 2014; pp. 211–238. [Google Scholar]

- Coombe, B.G.; Dry, P.R. (Eds.) Viticulture: Volume 1—Resources, 2nd ed.; Winetitles Pty Ltd.: Prospect East, Adelaide, Australia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Jackisch, P. Modern Winemaking; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Komárek, M.; Cadková, E.; Chrastný, V.; Bordas, F.; Bollinger, J.C. Contamination of vineyard soils with fungicides: A review of environmental and toxicological aspects. Environ. Int. 2010, 36, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epke, M.; Lawless, H.T. Retronasal smell and detection thresholds of iron and copper salts. Physiol. Behav. 2007, 92, 487–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burdock, G.A. Fenaroli’s Handbook of Flavor Ingredients, 6th ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce Goldstein, E. Sensation and Perception, 8th ed.; Wadsworth: Belmont, CA, USA, 2010; Chapter 15; Available online: http://zhenilo.narod.ru/main/students/Goldstein.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2018).

- Kreitman, G.Y.; Danilewicz, J.C.; Jeffery, D.W.; Elias, R.J. Reaction mechanisms of metals with hydrogen sulfide and thiols in model wine. Part 2: Iron- and Copper-Catalyzed Oxidation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 4105–4113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, A.; Duncan, S.E.; Dietrich, M. Effect of iron on taste perception and emotional response of sweetened beverage under different water conditions. Food Qual. Prefer. 2016, 54, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riemann, C.; Birke, M. (Eds.) Geochemistry of European Bottled Water; Borntraeger Science Publishers: Stuttgart, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, R.R.; Blackmore, D.H.; Clingeleffer, P.C.; Correll, R.L. Rootstock effects on salt tolerance of irrigated field-grown grapevines (Vitis vinifera L. cv. Sultana) 2. Ion concentrations in leaves and juice. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2004, 10, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, A.L.; Sacks, G.L.; Jeffery, D.W. Understanding Wine Chemistry; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wiesenthal, K.E.; McGuire, M.J.; Suffet, I.H. Characteristics of salt taste and free chlorine or chloramine in drinking water. Water Sci. Technol. 2007, 55, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fugelsang, K.C.; Edwards, C.G. Wine Microbiology: Practical Applications and Procedures, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bear, I.J.; Thomas, R.G. Genesis of petrichor. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1966, 30, 869–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bear, I.J.; Kranzs, Z.H. Fatty acids from exposed rock surfaces. Aust. J. Chem. 1965, 18, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bear, I.J.; Thomas, R.G. Nature of argillaceous odour. Nature 1964, 201, 993–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glindemann, D.; Dietrich, A.; Staerk, H.-J.; Kuschk, P. The two odors of iron when touched or pickled: (skin) carbonyl compounds and organophosphines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 7006–7009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capone, D.L.; Barker, A.; Williamson, P.O.; Francis, I.L. The role of potent thiols in Chardonnay wine aroma. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2017, 24, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelo, P.C.; Subramanian, R. Powder Metallurgy: Science, Technology and Applications; Prentice-Hall of India Pvt. Ltd.: New Delhi, India, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Parr, W.V.; Ballester, J.; Peyron, D.; Grose, C.; Valentin, D. Investigation of perceived minerality in Sauvignon wines: Influence of culture and mode of perception. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 41, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaldivar-Santamaria, E. Caracterizacion Quimico-Sensorial del Atributo « mineralidad » en Vinos Blancos y Tintos. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de La Rioja, Logroño, Spain, 30 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Parr, W.V.; Green, J.A.; White, K.G.; Sherlock, R.R. The distinctive flavour of New Zealand Sauvignon blanc: Sensory characterisation by wine professionals. Food Qual. Prefer. 2007, 18, 849–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, C.M.; Thompson, M.; Benkwitz, F.; Wohler, M.W.; Triggs, C.M.; Gardner, R.; Heymann, H.; Nicolau, L. New Zealand Sauvignon blanc distinct flavor characteristics: Sensory, chemical, and consumer aspects. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2009, 60, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Parr, W.V.; Valentin, D.; Green, J.A.; Dacremont, C. Evaluation of French and New Zealand Sauvignon wines by experienced French wine assessors. Food Qual. Prefer. 2010, 21, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.A.; Parr, W.V.; Breitmeyer, J.; Valentin, D.; Sherlock, R. Sensory and chemical characterisation of Sauvignon blanc wine: Influence of source of origin. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 2788–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, D.; Cliff, M.A.; Reynolds, A.G. Canadian terroir: Characterization of Riesling wines from the Niagara Peninsula. Food Res. Int. 2001, 34, 559–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, A.; Fischer, U. Factors causing sensory variation in Riesling wines from different Terroirs in Germany. In Proceedings of the 9th International Symposium of Enology of Bordeaux, Bordeaux, France, 15–17 June 2011; pp. 1087–1091. [Google Scholar]

- Heymann, H.; Hopfer, H.; Bershaw, D. An exploration of the perception of minerality in white wines by projective mapping and descriptive analysis. J. Sens. Stud. 2014, 29, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, P. Fragrance perception: From the nose to the brain. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2000, 51, 141–150. [Google Scholar]

- Goode, J. Minerality in wine. Sommel. J. 2012, 63–67. [Google Scholar]

- Mouret, M.; Lo Monaco, G.; Urdapilleta, I.; Parr, W.V. Social representations of wine and culture: A comparison between France and New Zealand. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 30, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, H.; Saenz-Navajas, M.-P.; Franco-Luesma, E.; Valentin, D.; Fernando-Zurbano, P.; Ferreira, V.; De La Fuente Blanco, A.; Ballester, J. Sensory and chemical drivers of wine minerality aroma: An application to Chablis wines. Food Chem. 2017, 230, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Easton, S. Minerality. Drinks Bus. 2009, 86–88. [Google Scholar]

- Jefford, A. Jefford on Monday: The Chablis Difference. Decanter. 2 July 2018. Available online: https://www.decanter.com/wine-news/opinion/jefford-on-monday/chablis-and-burgundy-difference-396329/ (accessed on 4 July 2018).

- Ross, J. Minerality: Rigorous or romantic? Pract. Winery Vineyard J. 2012, XXXIII, 50–57. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, I.M.; Gutierrez, A.J.; Rubio, C.; Gonzalez, A.G.; Gonzalez-Weller, D.; Bencharki, N.; Hardisson, A.; Revert, C. Classification of Spanish red wines using neural networks with enological parameters and mineral content. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2018, 69, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabello-Pasini, A.; Macias-Carranza, V.; Siqueiros-Valencia, A.; Huerta-Diaz, M.A. Concentrations of calcium, magnesium, potassium and sodium in wines from Mexico. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2013, 64, 280–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, M.; Fiala, J. Chasing after minerality, relationship to yeast nutritional stress and succinic acid production. Czech J. Food Sci. 2012, 30, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parr, W.V.; Valentin, D.; Breitmeyer, J.; Peyron, D.; Darriet, P.; Sherlock, R.R.; Robinson, B.; Grose, C.; Ballester, J. Perceived minerality in Sauvignon blanc wine: Chemical reality or cultural construct? Food Res. Int. 2016, 87, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starkenmann, C.; Chappuis, C.J.-F.; Niclass, Y.; Deneulin, P. Identification of hydrogen disulfanes and hydrogen trisulfanes in H2S bottle, in flint, and in dry mineral white wine. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 9033–9040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tominaga, T.; Guimbertau, G.; Dubourdieu, D. Contribution of benzenemethanethiol to smoky aroma of certain Vitis vinifera L. wines. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 1373–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawless, H.T.; Schlake, S.; Smythe, J.; Lim, J.; Yang, H.; Chapman, K.; Bolton, B. Metallic taste and retronasal smell. Chem. Sens. 2004, 29, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tominaga, T.; Baltenweck-Guyot, R.; Peyrot des Gachons, C.; Dubourdieu, D. Contribution of volatile thiols to the aromas of white wines made from several Vitis vinifera grape varieties. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2000, 51, 178–181. [Google Scholar]

- Goode, J. The Science of Wine: From Vine to Glass; Octopus Publishing Group Ltd.: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, V.; Ortin, N.; Escudero, A.; Lopez, R.; Cacho, J. Chemical characterization of the aroma of Grenache Rose wines: Aroma extract dilution analysis, quantitative determination and sensory reconstitution studies. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 4048–4054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pineau, B.; Barbe, J.-C.; Van Leeuwen, C.; Dubourdieu, D. Which Impact for β-Damascenone on Red Wines Aroma? J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 4103–4108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorrain, B.; Ballester, J.; Thomas-Danguin, T.; Blanquet, J.; Meunier, J.-M.; Le Fur, Y. Selection of potential impact odorants and sensory validation of their importance in typical Chardonnay wines. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 3973–3981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomasino, E.; Harrison, R.; Breitmeyer, J.; Sedcole, R.; Sherlock, R.; Frost, A. Aroma composition of 2-year-old New Zealand pinot noir wine and its relationship to sensory characteristics using canonical correlation analysis and addition/omission tests. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2015, 21, 376–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sensory Dimension § | Compound | Positive # | Negative # |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reductive/gunflint [2,3,7,43,51,55,63] | benzenemethanethiol | [41,64] | |

| disulphane | [63] | ||

| Reductive [2,43] | free SO2 | [51,62] | |

| bound SO2 | [62] | ||

| Cu | [55] | ||

| Reductive/seashore [2,7] | methanethiol | [55] | |

| Lack of fruit [2,43,55] | damascenone | [55] | |

| Citrus [43,51] | 3-mercapto-1-hexanol | [62] | |

| Acidity/freshness [2,3,7,43,44,51] | titratable acidity | [51] | [62] |

| pH | [44] | ||

| tartaric acid | [44,51] | [62] | |

| malic acid | [51,62] | ||

| lactic acid | [51] | ||

| Saltiness [2,7] | Na | [62] | |

| Sweetness [44] | glucose + fructose | [44] | |

| No particular sensory dimension | isoamyl acetate | [62] | |

| hexanoic acid | [62] | ||

| isoamyl alcohol | [62] | ||

| diethyl succinate | [62] | ||

| isobutanol | [62] | ||

| glucose + fructose | [44] | ||

| Mg | [44] | ||

| K | [44] |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Parr, W.V.; Maltman, A.J.; Easton, S.; Ballester, J. Minerality in Wine: Towards the Reality behind the Myths. Beverages 2018, 4, 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages4040077

Parr WV, Maltman AJ, Easton S, Ballester J. Minerality in Wine: Towards the Reality behind the Myths. Beverages. 2018; 4(4):77. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages4040077

Chicago/Turabian StyleParr, Wendy V., Alex J. Maltman, Sally Easton, and Jordi Ballester. 2018. "Minerality in Wine: Towards the Reality behind the Myths" Beverages 4, no. 4: 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages4040077

APA StyleParr, W. V., Maltman, A. J., Easton, S., & Ballester, J. (2018). Minerality in Wine: Towards the Reality behind the Myths. Beverages, 4(4), 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages4040077