Bioactivity of Fucoidan as an Antimicrobial Agent in a New Functional Beverage

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Listeria Monocytogenes

2.2. Salmonella Enterica Serovar Typhimurium

2.3. Fucoidan Suspension Preparation

2.4. Inoculum and Incubation Conditions

2.5. Growth Kinetic Study under Fucoidan Exposure

2.6. Formulation of a New Functional Apple Juice Beverage

2.7. Statistical Analysis of Data

3. Results

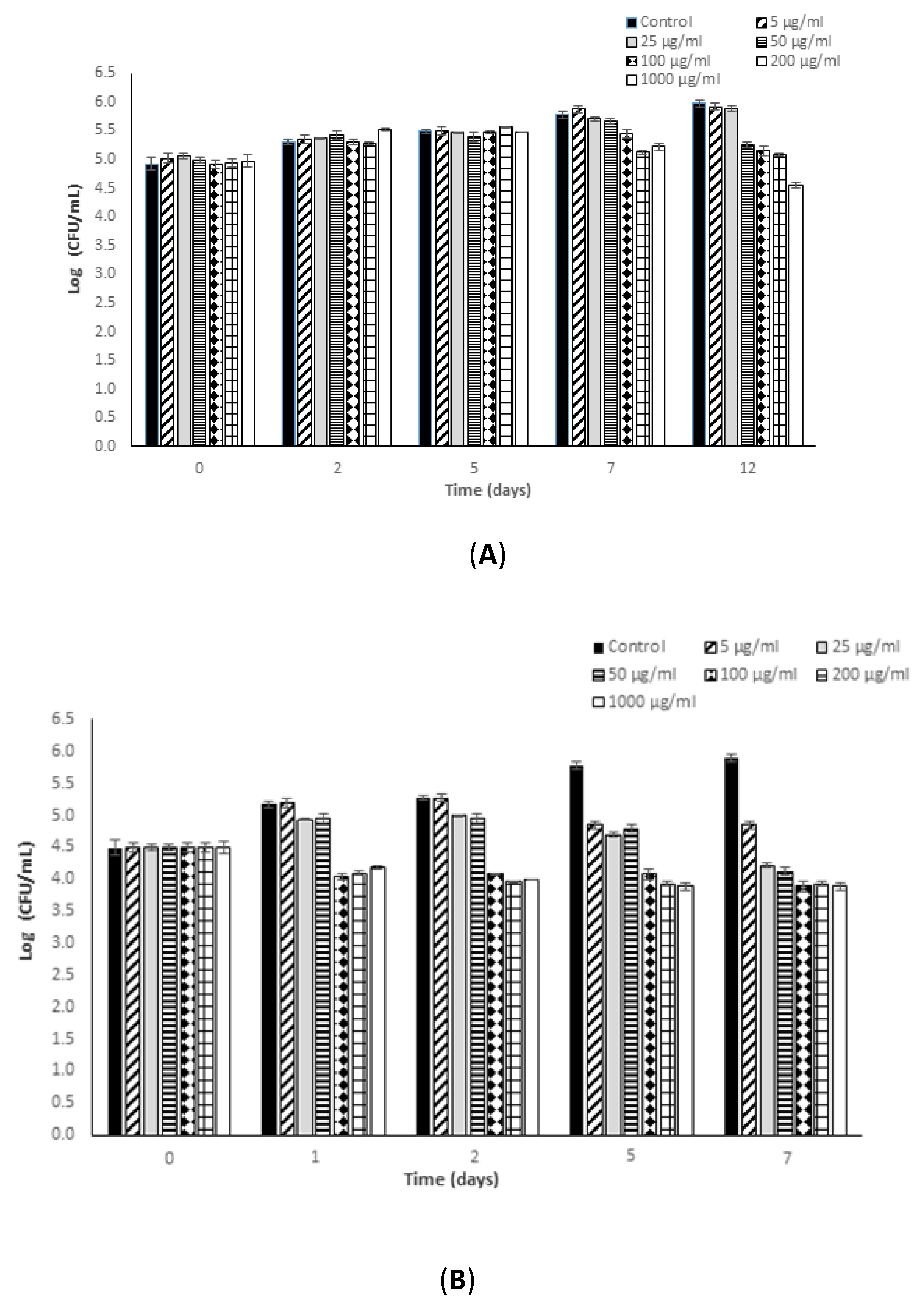

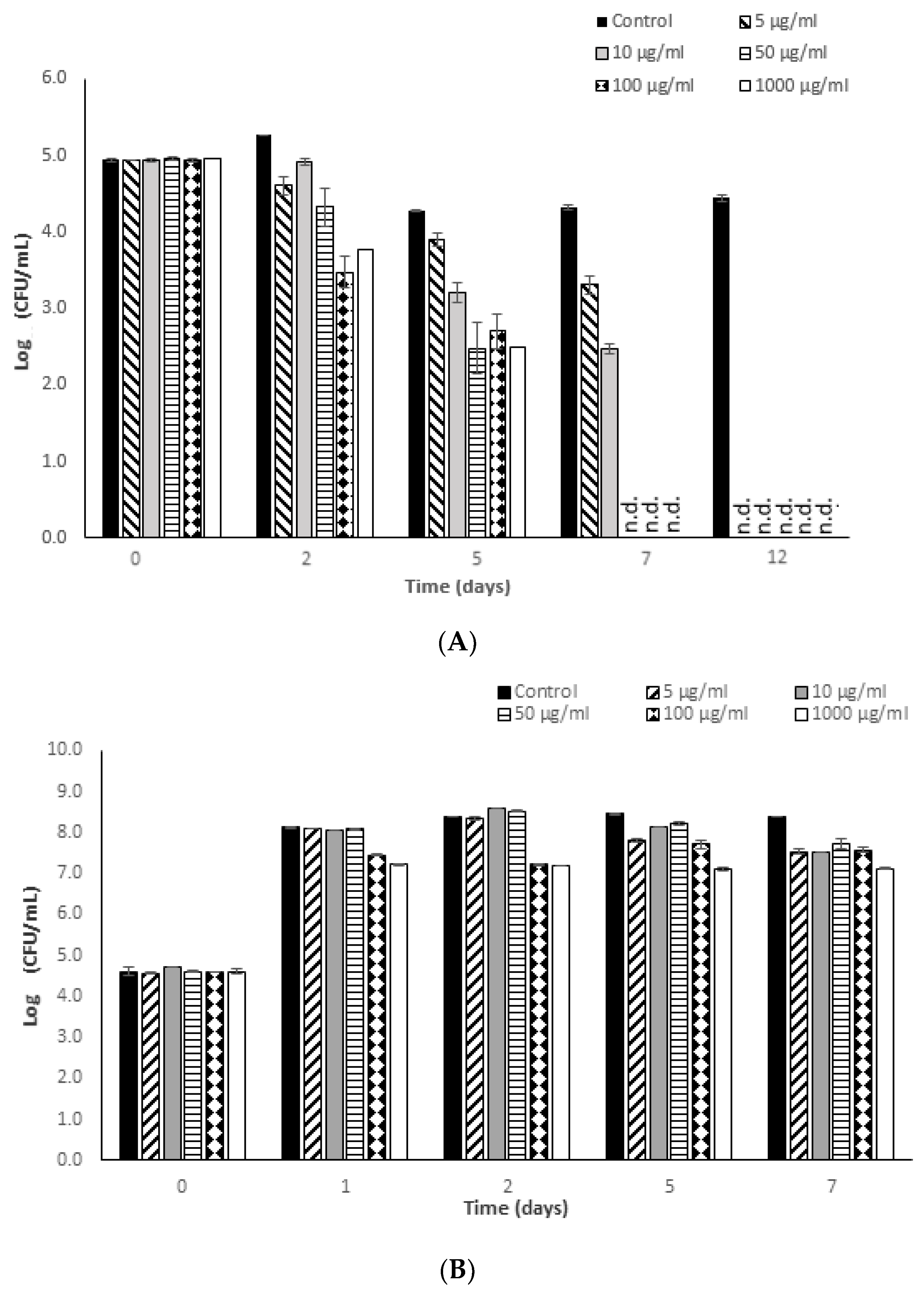

3.1. Antimicrobial Potential of Fucoidan against L. monocytogenes

3.2. Antimicrobial Potential of Fucoidan against S. typhimurium

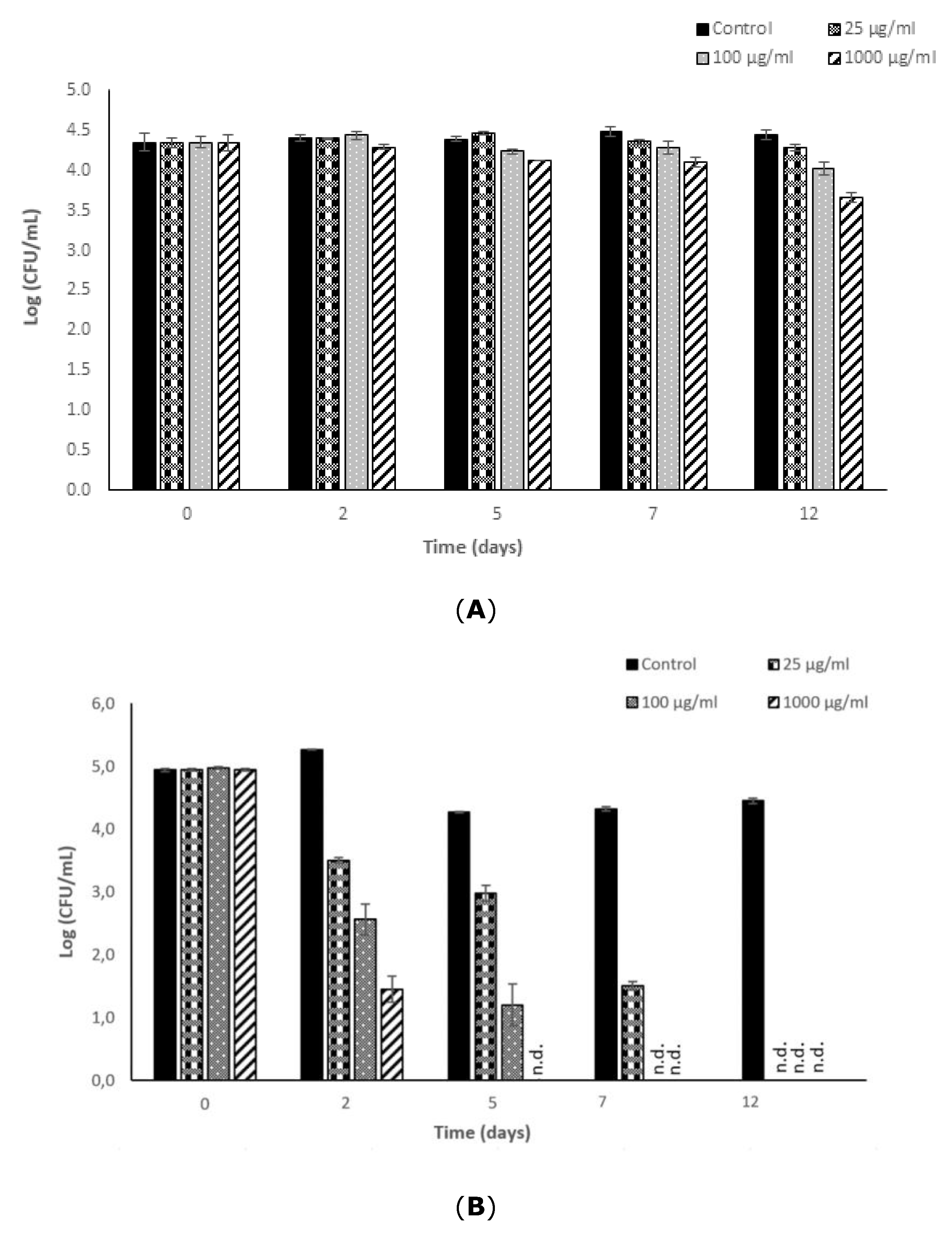

3.3. Effectiveness of Fucoidan Derived from Fucus Vesiculosus against L. monocytogenes and S. typhimurium in a Newly Formulated Apple Juice Beverage

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Miyashita, K.; Mikami, N.; Hosokawa, M. Chemical and nutritional characteristics of brown seaweed lipids: A review. J. Funct. Foods 2013, 5, 1507–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susanto, E.; Suhaeli Fahmi, A.; Abe, M.; Hosokawa, M.; Miyashita, K. Lipids, fatty acids, and fucoxanthin content from temperate and tropical brown seaweeds. Aquat. Proc. 2016, 7, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, M.L.; Potin, P.; Craigie, J.S.; Raven, J.A.; Merchant, S.S.; Helliwell, K.E.; Smith, A.G.; Camire, M.E.; Brawley, S.H. Algae as nutritional and functional food sources: Revisiting our understanding. J. Appl. Phycol. 2017, 29, 949–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peinado, I.; Girón, J.; Koutsidis, G.; Ames, J.M. Chemical composition, antioxidant activity and sensory evaluation of five different species of brown edible seaweeds. Food Res. Int. 2014, 66, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, L.; Murphy, B.; McLoughlin, P.; Duggan, P.; Lawlor, P.G.; Hughes, H.; Gardiner, G.E. Prebiotics from marine macroalgae for human and animal health applications. Mar. Drugs 2010, 8, 2038–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCusker, S.; Buff, P.R.; Yu, Z.; Fascetti, A.J. Amino acid content of selected plant, algae and insect species: a search for alternative protein sources for use in pet foods. J. Nutr. Sci. 2014, 3, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J. Antibacterial effect of extracts from two Icelandic algae (Ascophyllumnodosum and Laminariadigitata). United Nations University, Fisheries Training Programme. 2010, pp. 1–37. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/9224/a0f05bbb3331cf7fa9afbb9e57ecede26c50.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2018).

- De Jesus Raposo, M.; De Morais, A.; De Morais, R. Marine polysaccharides from algae with potential biomedical applications. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 2967–3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moghadamtousi, S.Z.; Karimian, H.; Khanabdali, R.; Razavi, M.; Firoozinia, M.; Zandi, K.; Kadir, H.A. Anticancer and antitumor potential of fucoidan and fucoxanthin, two main metabolites isolated from brown algae. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tutor Ale, M.; Mikkelsen, J.D.; Meyer, A.S. Important determinants for fucoidan bioactivity: A critical review of structure-function relations and extraction methods for fucose-containing sulfated polysaccharides from brown seaweeds. Mar. Drugs 2011, 9, 2106–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijesekara, I.; Pangestuti, R.; Kim, S.K. Biological activities and potential health benefits of sulphated polysaccharides derived from marine algae. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 84, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.M.; Jang, E.J.; Cha, J.D. Synergistic effect between fucoidan and antibiotics against clinic methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Adv. Biosci. Biotechnol. 2015, 6, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, E.; Abu-Ghannam, N. Antibacterial derivatives of marine algae: An overview of pharmacological mechanisms and applications. Mar. Drugs 2016, 14, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, T.H.; Alves, A.; Popa, E.G.; Reys, L.; Gomes, M.E.; Sousa, R.A.; Silva, S.S.; Mano, J.F.; Reis, R.L. Marine algae sulfated polysaccharides for tissue engineering and drug delivery approaches. Biomaterials 2012, 2, 278–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besednova, N.; Zaporozhets, T.; Somova, L.; Kuznetsova, T. Review: Prospects for the use of extracts and polysaccharides from marine algae to prevent and treat the diseases caused by Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter 2015, 20, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.H.; Wu, S.J.; Wu, J.Y.; Wen, D.Y.; Mi, F. Preparation of fucoidan-shelled and genipin-crosslinked chitosan beads for antibacterial application. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 126, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, F.; Yang, Y.; Yang, G.; Yu, L. Studies on antibacterial activity and antibacterial mechanism of a novel polysaccharide from Streptomyces virginia H03. Food Control 2010, 21, 1257–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marudhupandi, T.; Thangappan, T.K.A. Antibacterial effect of fucoidan from Sargassum wightii against the chosen human bacterial pathogens. Int. Curr. Pharm. J. 2013, 2, 156–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Gooneratne, R.; Altaf Hussain, M. Listeria monocytogenes in fresh produce: Outbreaks, prevalence and contamination levels. Foods 2017, 6, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanz-Puig, M.; Pina-Pérez, M.C.; Martínez-López, A.; Rodrigo, D. Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Salmonella typhimurium inactivation by the effect of mandarin, lemon, and orange by-products in reference medium and in oat-fruit juice mixed beverage. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 66, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saucedo-Reyes, D.; Marco-Celdrán, A.; Pina-Pérez, M.C.; Rodrigo, D.; Martínez López, A. Modeling survival of high hydrostatic pressure treated stationary and exponential phase Listeria innocua cells. Inn. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2009, 10, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.Y.; Jeong, M.R.; Choi, S.M.; Na, S.S.; Cha, J. Synergistic effect of fucoidan with antibiotics against oral pathogenic bacteria. Archives Oral Biol. 2013, 58, 482–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, P.A.; Phan, N.N.; Lu, W.J.; Ngoc Hieu, B.T.; Lin, Y.C. Low-molecular-weight fucoidan and high-stability fucoxanthin from brown seaweed exert prebiotics and anti-inflammatory activities in Caco-2 cells. Food Nutr. Res. 2016, 60, 32033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, I.S.; Slonczewski, J.L.; Foster, J.W. A low-pH-inducible, stationary-phase acid tolerance response in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 1994, 176, 1422–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez-Ordóñez, A.; Fernández, A.; Bernardo, A.; López, M. Acid tolerance in Salmonella typhimurium induced by culturing in the presence of organic acids at different growth temperatures. Food Microbiol. 2010, 27, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandhi, M.; Chikindas, M. Listeria: A foodborne pathogen that knows how to survive. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2007, 113, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belda-Galbis, C.M.; Leufvén, A.; Martínez, A.; Rodrigo, D. Predictive microbiology quantification of the antimicrobial effect of carvacrol. J. Food Eng. 2014, 141, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belda-Galbis, C.M.; Jiménez-Carretón, A.; Pina-Pérez, M.C.; Martínez, A.; Rodrigo, D. Antimicrobial activity of açaí against Listeria innocua. Food Control 2015, 53, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroney, N.C.; O’Grady, M.N.; Lordan, S.; Stanton, C.; Kerry, J.P. Seaweed polysaccharides (laminarin and fucoidan) as functional ingredients in pork meat: An evaluation of anti-oxidative potential, thermal stability and bioaccessibility. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 2447–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ammar, H.H.; Lajili, S.; Said, R.B.; Le Cerf, D.; Bouraoui, A.; Majdoub, H. Physico-chemical characterization and pharmacological evaluation of sulfated polysaccharides from three species of Mediterranean brown algae of the genus Cystoseira. DRAU J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 23, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashima, R.S.; Maizura, M.; Kang, W.M.; Fazilah, A.; Tan, L.X. Influence of sodium chloride treatment and polysaccharides as debittering agent on the physicochemical properties, antioxidant capacity and sensory characteristics of bitter gourd (Momordica charantia) juice. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Temperature | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 37 °C | 8 °C | |||||

| Substrates | µg/mL | Exposure time (days) | Log10 cycles | µg/mL | Exposure time (days) | Log cycles |

| Listeria monocytogenes | ||||||

| Mueller Hinton Broth (MHB) | ||||||

| MIC | 5 | 5 | 1.55 ± 0.04 | 100 | 7 | 0.83 ± 0.08 |

| MBC | 100 | 1 | 0.61 ± 0.03 | 50 | 12 | 0.89 ± 0.13 |

| Apple juice | µg/mL | Exposure time (days) | Log10 cycles | µg/mL | Exposure time (days) | Log cycles |

| MIC | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| MBC | - | - | - | 1000 | 12 | 0.70 ± 0.06 |

| Salmonella typhimurium | ||||||

| Mueller Hinton Broth (MHB) | ||||||

| MIC | 1000 | 7 | 1.08 ± 0.23 | - | - | - |

| MBC | - | - | - | 10 | 2 | 1.25 ± 0.15 |

| Apple juice | µg/mL | Exposure time (days) | Log10 cycles | µg/mL | Exposure time (days) | Log cycles |

| MIC | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| MBC | - | - | - | 25 | 2 | 1.52 ± 0.08 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Poveda-Castillo, G.D.C.; Rodrigo, D.; Martínez, A.; Pina-Pérez, M.C. Bioactivity of Fucoidan as an Antimicrobial Agent in a New Functional Beverage. Beverages 2018, 4, 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages4030064

Poveda-Castillo GDC, Rodrigo D, Martínez A, Pina-Pérez MC. Bioactivity of Fucoidan as an Antimicrobial Agent in a New Functional Beverage. Beverages. 2018; 4(3):64. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages4030064

Chicago/Turabian StylePoveda-Castillo, Gabriela Del Carmen, Dolores Rodrigo, Antonio Martínez, and Maria Consuelo Pina-Pérez. 2018. "Bioactivity of Fucoidan as an Antimicrobial Agent in a New Functional Beverage" Beverages 4, no. 3: 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages4030064

APA StylePoveda-Castillo, G. D. C., Rodrigo, D., Martínez, A., & Pina-Pérez, M. C. (2018). Bioactivity of Fucoidan as an Antimicrobial Agent in a New Functional Beverage. Beverages, 4(3), 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/beverages4030064