Trophic Drivers of Organochlorine and PFAS Accumulation in Mediterranean Smooth-Hound Sharks: Insights from Stable Isotopes and Human Health Risk

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples Collection and Sampling Activities

2.2. Organochlorine Contaminant Determination

2.3. Per- Polyfluoroalkyl Substances Determination

2.4. Stable Isotopes Analysis (SIA)

2.5. Statistical Analyses

2.6. Human Health Risk Assessment

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Biological Parameters

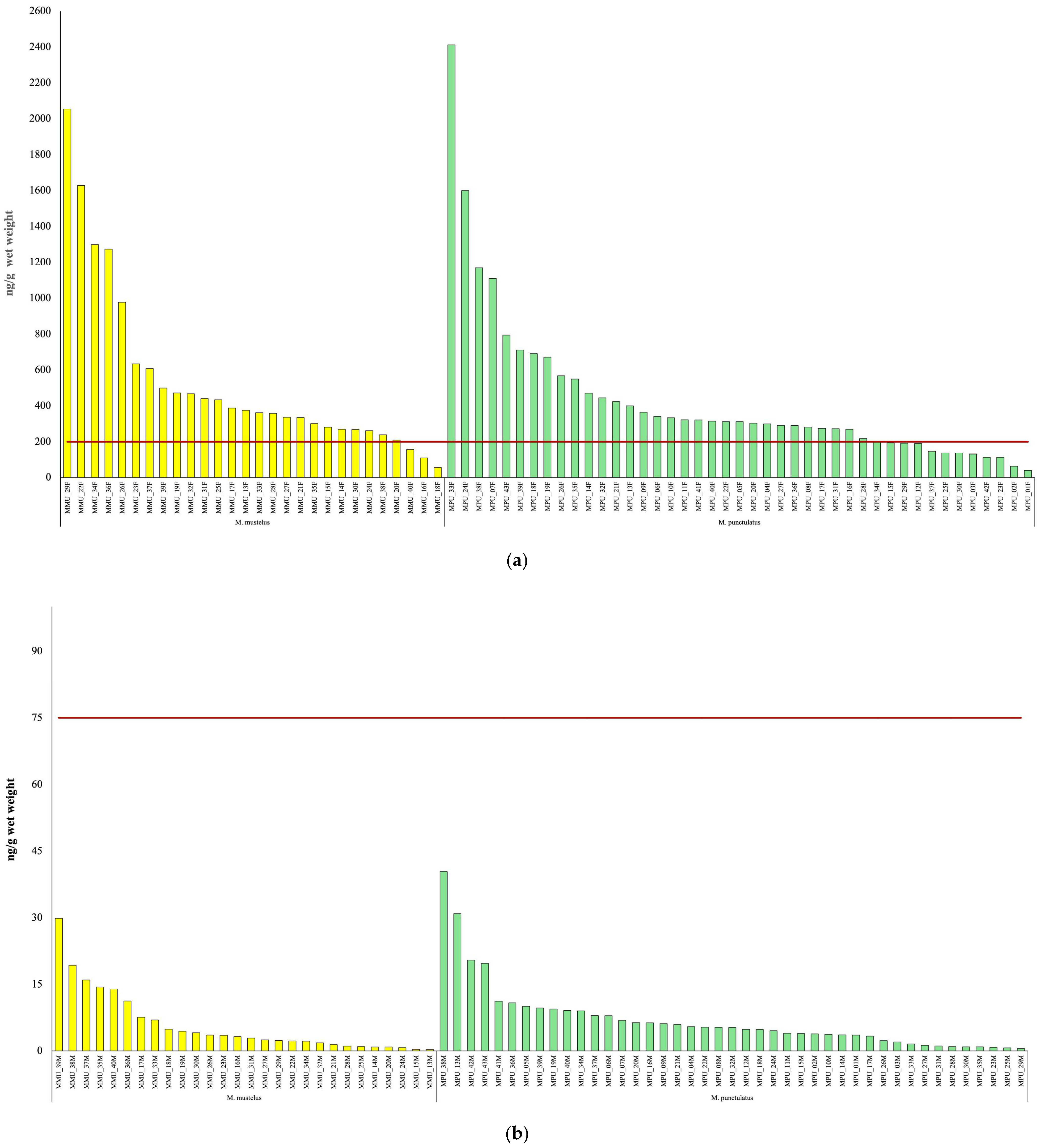

3.2. Organochlorine Compounds Distribution

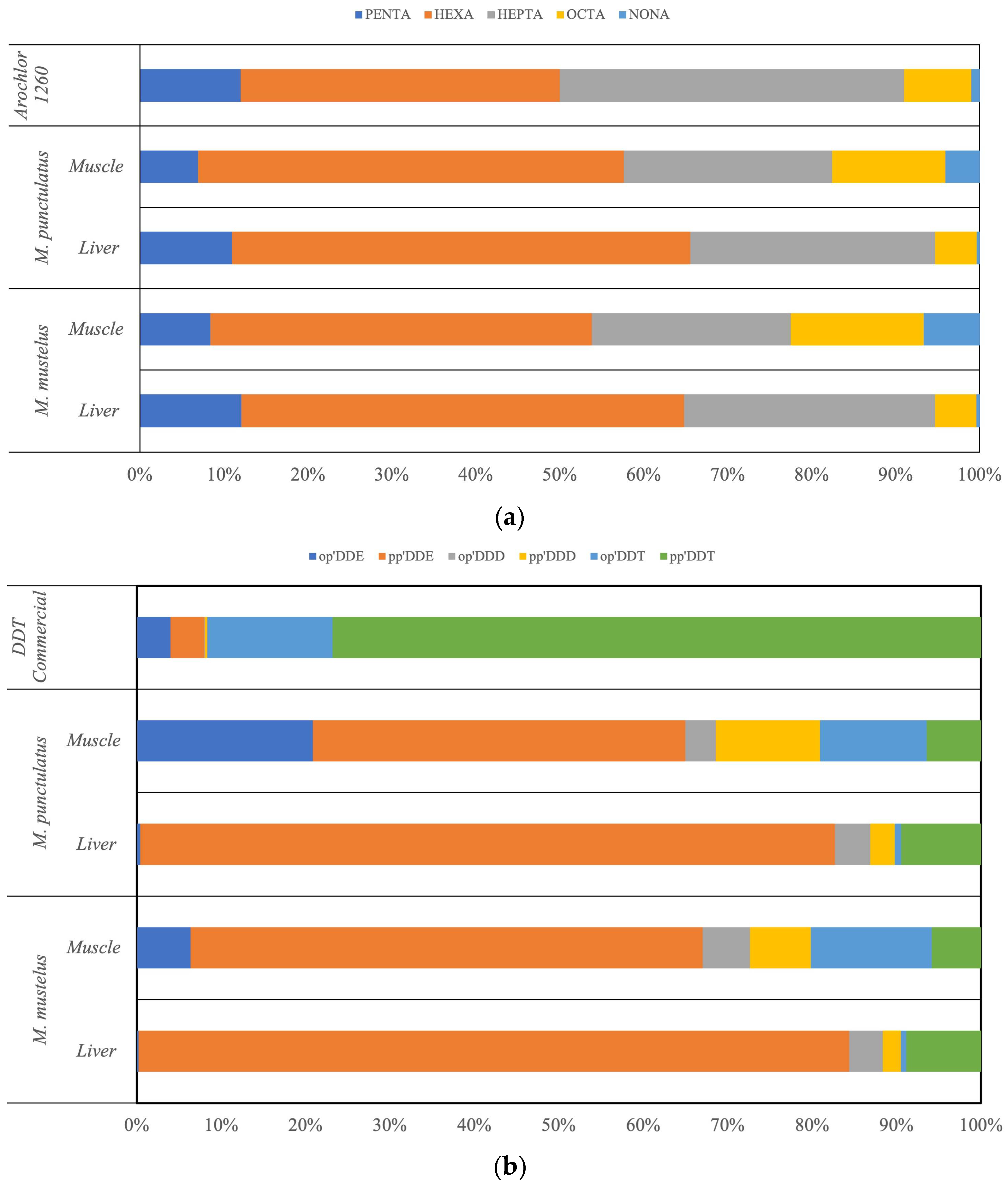

PCB and DDT Profiles

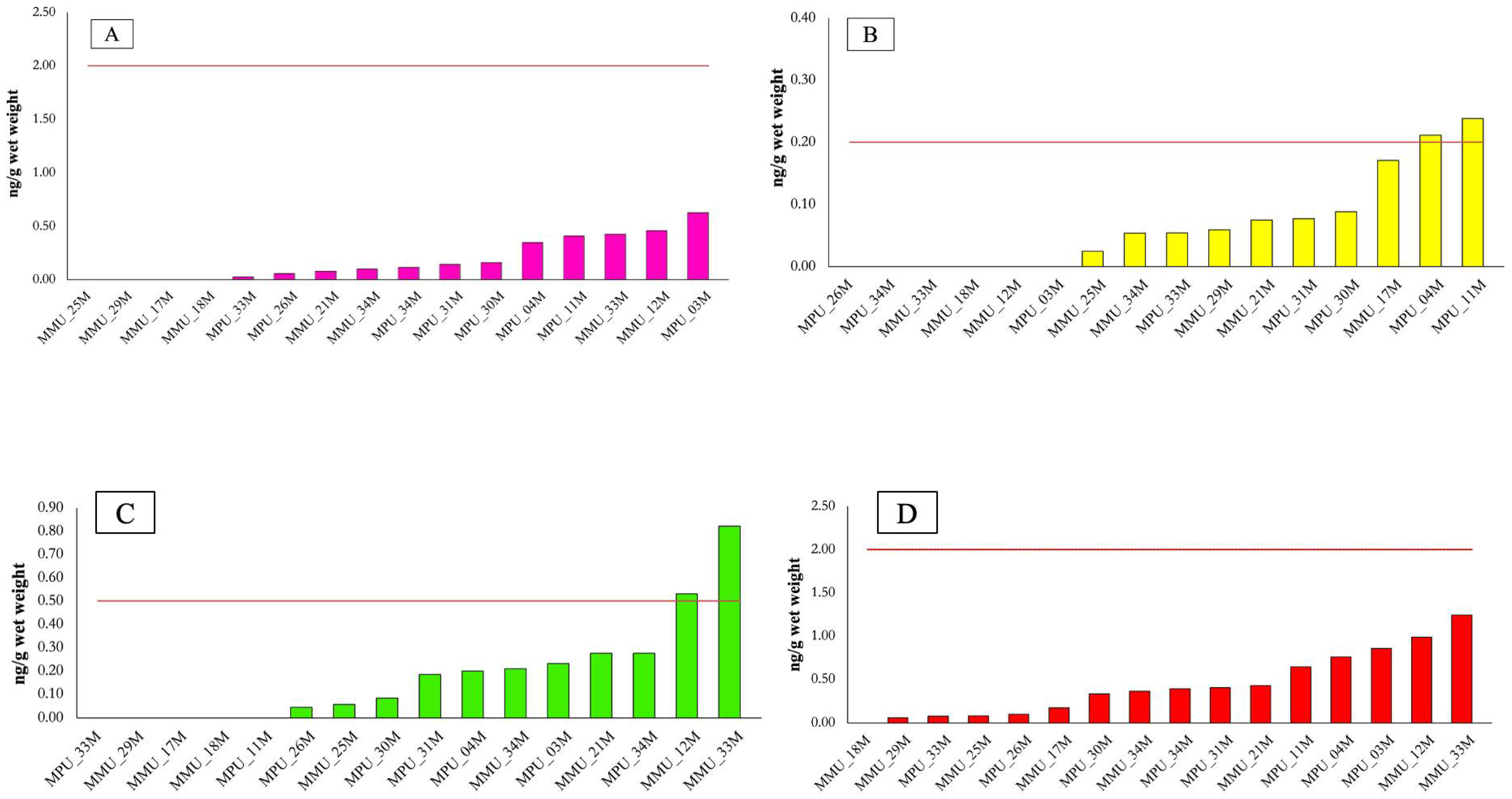

3.3. PFAS Contamination Levels in Elasmobranch Tissues

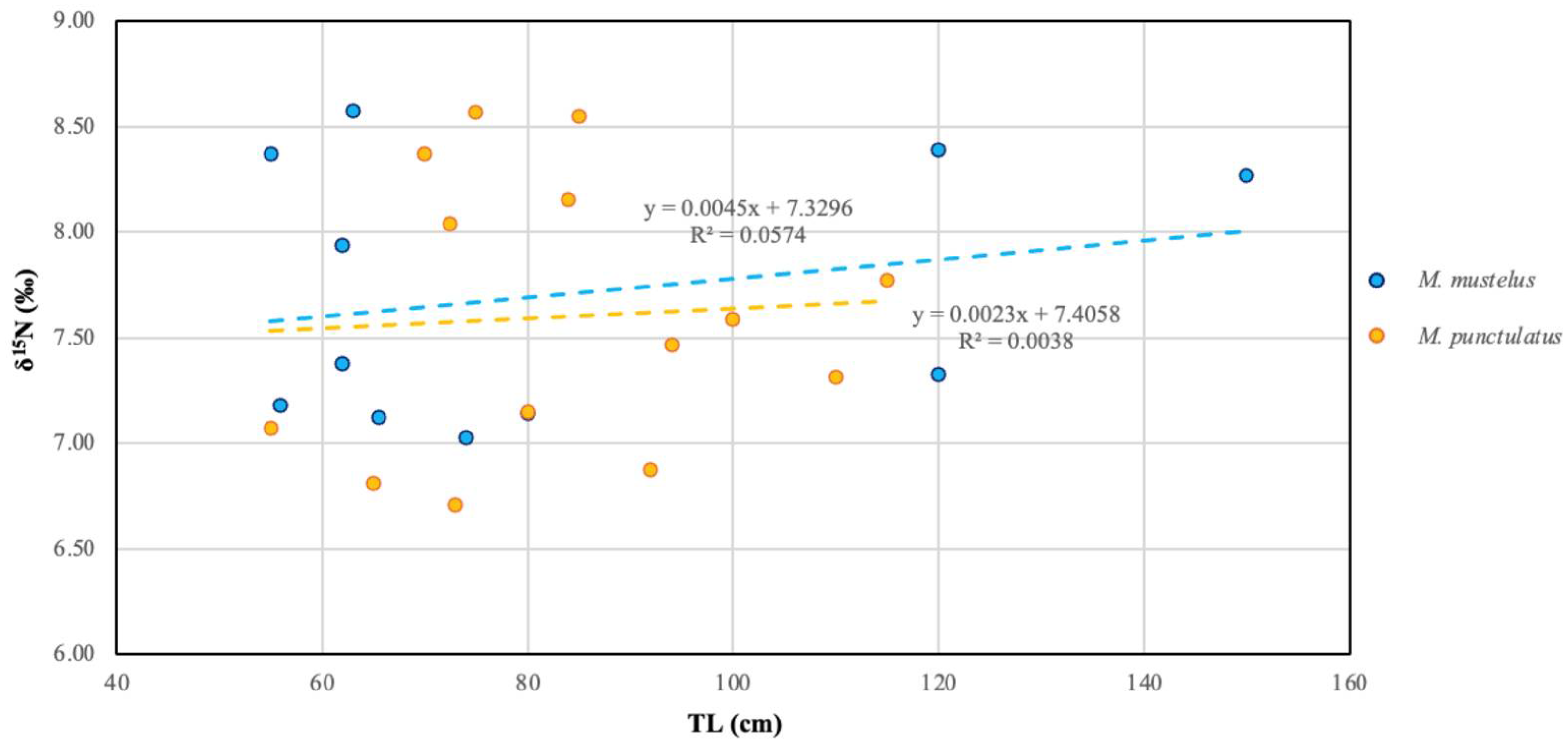

3.4. Stable Isotopes Analysis (δ13C and δ15N)

3.4.1. Comparative Interpretation of OCs and Stable Isotopes

Levels of OCs in Relation to δ13C and δ15N

3.4.2. PFAS Concentrations in Relation to δ13C and δ15N

3.5. Human Consumption and Exposure Risk Assessment

3.5.1. OCs Evaluation in Exposure Risk Assessment

3.5.2. PFAS Evaluation in Exposure Risk Assessment

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Coll, M.; Piroddi, C.; Steenbeek, J.; Kaschner, K.; Lasram, F.B.R.; Aguzzi, J.; Ballesteros, E.; Bianchi, C.N.; Corbera, J.; Dailianis, T.; et al. The Biodiversity of the Mediterranean Sea: Estimates, Patterns, and Threats. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e11842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danovaro, R.; Fanelli, E.; Canals, M.; Ciuffardi, T.; Fabri, M.-C.; Taviani, M.; Argyrou, M.; Azzurro, E.; Bianchelli, S.; Cantafaro, A.; et al. Towards a Marine Strategy for the Deep Mediterranean Sea: Analysis of Current Ecological Status. Mar. Policy 2020, 112, 103781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, C.N.; Morri, C. Marine Biodiversity of the Mediterranean Sea: Situation, Problems and Prospects for Future Research. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2000, 40, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Navarro, J.; Jordá, G.; Compa, M.; Alomar, C.; Fossi, M.C.; Deudero, S. Impact of the Marine Litter Pollution on the Mediterranean Biodiversity: A Risk Assessment Study with Focus on the Marine Protected Areas. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 165, 112169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serena, F.; Abella, A.J.; Bargnesi, F.; Barone, M.; Colloca, F.; Ferretti, F.; Fiorentino, F.; Jenrette, J.; Moro, S. Species Diversity, Taxonomy and Distribution of Chondrichthyes in the Mediterranean and Black Sea. Eur. Zool. J. 2020, 87, 497–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrojalbiz, N.; Dachs, J.; Del Vento, S.; Ojeda, M.J.; Valle, M.C.; Castro-Jiménez, J.; Mariani, G.; Wollgast, J.; Hanke, G. Persistent Organic Pollutants in Mediterranean Seawater and Processes Affecting Their Accumulation in Plankton. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 4315–4322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casini, S.; Caliani, I.; Giannetti, M.; Marsili, L.; Maltese, S.; Coppola, D.; Bianchi, N.; Campani, T.; Ancora, S.; Caruso, C.; et al. First Ecotoxicological Assessment of Caretta Caretta (Linnaeus, 1758) in the Mediterranean Sea Using an Integrated Nondestructive Protocol. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 631–632, 1221–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsili, L.; Jiménez, B.; Borrell, A. Persistent Organic Pollutants in Cetaceans Living in a Hotspot Area: The Mediterranean Sea. In Marine Mammal Ecotoxicology; Fossi, M.C., Panti, C., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 185–212. ISBN 978-0-12-812144-3. [Google Scholar]

- Dulvy, N.K.; Allen, D.; Ralph, G.; Walls, R.H.L. The Conservation Status of Sharks, Rays and Chimaeras in the Mediterranean Sea; International Union for Conservation of Nature: Gland, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi, F.; Lionello, P. Climate Change Projections for the Mediterranean Region. Glob. Planet. Change 2008, 63, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, W.; Guiot, J.; Fader, M.; Garrabou, J.; Gattuso, J.-P.; Iglesias, A.; Lange, M.A.; Lionello, P.; Llasat, M.C.; Paz, S.; et al. Climate Change and Interconnected Risks to Sustainable Development in the Mediterranean. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 972–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Franco, E.; Pierson, P.; Di Iorio, L.; Calò, A.; Cottalorda, J.M.; Derijard, B.; Di Franco, A.; Galvé, A.; Guibbolini, M.; Lebrun, J.; et al. Effects of Marine Noise Pollution on Mediterranean Fishes and Invertebrates: A Review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 159, 111450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vincenzi, G.; Micarelli, P.; Viola, S.; Buffa, G.; Sciacca, V.; Maccarrone, V.; Corrias, V.; Reinero, F.R.; Giacoma, C.; Filiciotto, F. Biological Sound vs. Anthropogenic Noise: Assessment of Behavioural Changes in Scyliorhinus Canicula Exposed to Boats Noise. Animals 2021, 11, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchetti, A.; Carbonara, P.; Colloca, F.; Lanteri, L.; Spedicato, M.T.; Sartor, P. Small-Scale Driftnets in the Mediterranean: Technical Features, Legal Constraints and Management Options for the Reduction of Protected Species Bycatch. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2017, 135, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargagli, R.; Rota, E. Mediterranean Marine Mammals: Possible Future Trends and Threats Due to Mercury Contamination and Interaction with Other Environmental Stressors. Animals 2024, 14, 2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossi, M.C.; Limonta, G.; Baini, M.; Urban, R.J.; Athanassiadis, I.; Martin, J.W.; Papazian, S.; Rosso, M.; Panti, C. Fin Whale as a Sink of Legacy and Emerging Contaminants: First Integrated Chemical Exposomics and Gene Expression Analysis in Cetaceans. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 11477–11492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsili, L.; Focardi, S. Chlorinated Hydrocarbon (HCB, DDTs and PCBs Levels in Cetaceans Stranded Along the Italian Coasts: An Overview. Environ. Monit. Assess. 1997, 45, 129–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossi, M.C.; Marsili, L. Effects of endocrine disruptors in aquatic mammals. Pure Appl. Chem. 2003, 75, 2235–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Impellitteri, F.; Multisanti, C.R.; Rusanova, P.; Piccione, G.; Falco, F.; Faggio, C. Exploring the Impact of Contaminants of Emerging Concern on Fish and Invertebrates Physiology in the Mediterranean Sea. Biology 2023, 12, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capanni, F.; Karamanlidis, A.A.; Dendrinos, P.; Zaccaroni, A.; Formigaro, C.; D’Agostino, A.; Marsili, L. Monk Seals (Monachus monachus) in the Mediterranean Sea: The Threat of Organochlorine Contaminants and Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 915, 169854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Q.; Gan, Y.; Zhou, J.; Dai, J.; Cao, H.; Xu, M. Bioaccumulation and biomagnification of Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) in food Chain. Chin. J. Appl. Environ. Biol. 2007, 13, 901–905. [Google Scholar]

- Cousins, I.T.; De Witt, J.C.; Glüge, J.; Goldenman, G.; Herzke, D.; Lohmann, R.; Ng, C.A.; Scheringer, M.; Wang, Z. The High Persistence of PFAS Is Sufficient for Their Management as a Chemical Class. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2020, 22, 2307–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebbink, W.A.; Bossi, R.; Rigét, F.F.; Rosing-Asvid, A.; Sonne, C.; Dietz, R. Observation of Emerging Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) in Greenland Marine Mammals. Chemosphere 2016, 144, 2384–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunderland, E.M.; Hu, X.C.; Dassuncao, C.; Tokranov, A.K.; Wagner, C.C.; Allen, J.G. A Review of the Pathways of Human Exposure to Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) and Present Understanding of Health Effects. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2019, 29, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, C.; Anitole, K.; Hodes, C.; Lai, D.; Pfahles-Hutchens, A.; Seed, J. Perfluoroalkyl Acids: A Review of Monitoring and Toxicological Findings. Toxicol. Sci. 2007, 99, 366–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, P.S.; Birnbaum, L.S. Integrated Human and Ecological Risk Assessment: A Case Study of Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) in Humans and Wildlife. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. Int. J. 2003, 9, 303–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossi, M.C.; Panti, C. Sentinel Species of Marine Ecosystems. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Environmental Science; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-0-19-938941-4. [Google Scholar]

- Marsili, L.; Coppola, D.; Giannetti, M.; Casini, S.; Fossi, M.C.; van Wyk, J.H.; Sperone, E.; Tripepi, S.; Micarelli, P.; Rizzuto, S. Skin Biopsies as a Sensitive Non-Lethal Technique for the Ecotoxicological Studies of Great White Shark(Carcharodon carcharias) Sampled in South Africa. Expert. Opin. Environ. Biol. 2015, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-S.; Shipley, O.N.; Ye, X.; Fisher, N.S.; Gallagher, A.J.; Frisk, M.G.; Talwar, B.S.; Schneider, E.V.C.; Venkatesan, A.K. Accumulation of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in Coastal Sharks from Contrasting Marine Environments: The New York Bight and the Bahamas. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 13087–13098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossi, M.C.; Marsili, L.; Neri, G.; Natoli, A.; Politi, E.; Panigada, S. The Use of a Non-Lethal Tool for Evaluating Toxicological Hazard of Organochlorine Contaminants in Mediterranean Cetaceans: New Data 10 Years after the First Paper Published in MPB. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2003, 46, 972–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centelleghe, C.; Da Dalt, L.; Marsili, L.; Zanetti, R.; Fernandez, A.; Arbelo, M.; Sierra, E.; Castagnaro, M.; Di Guardo, G.; Mazzariol, S. Insights Into Dolphins’ Immunology: Immuno-Phenotypic Study on Mediterranean and Atlantic Stranded Cetaceans. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsili, L.; Di Guardo, G.; Mazzariol, S.; Casini, S. Insights Into Cetacean Immunology: Do Ecological and Biological Factors Make the Difference? Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritscher, A.; Wang, Z.; Scheringer, M.; Boucher, J.M.; Ahrens, L.; Berger, U.; Bintein, S.; Bopp, S.K.; Borg, D.; Buser, A.M.; et al. Zürich Statement on Future Actions on Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs). Environ. Health Perspect. 2018, 126, 084502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Arnanz, J.; Bartalini, A.; Alves, L.; Lemos, M.F.L.; Novais, S.C.; Jiménez, B. Occurrence and Distribution of Persistent Organic Pollutants in the Liver and Muscle of Atlantic Blue Sharks: Relevance and Health Risks. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 309, 119750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiktak, G.P.; Butcher, D.; Lawrence, P.J.; Norrey, J.; Bradley, L.; Shaw, K.; Preziosi, R.; Megson, D. Are Concentrations of Pollutants in Sharks, Rays and Skates (Elasmobranchii) a Cause for Concern? A Systematic Review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 160, 111701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldrocchi, G.; Monticelli, D.; Omar, Y.M.; Bettinetti, R. Trace Elements and POPs in Two Commercial Shark Species from Djibouti: Implications for Human Exposure. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 669, 637–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heupel, M.R.; Knip, D.M.; Simpfendorfer, C.A.; Dulvy, N.K. Sizing up the Ecological Role of Sharks as Predators. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2014, 495, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzón-Peña, L.V.; Barrera-García, A.; Delgado-Huertas, A.; Polo-Silva, C. Trophic Ecology of Four Shark Species in the Gulf of Salamanca, Colombian Caribbean, Using Multi-Tissue Stable Isotopes Analysis. J. Fish Biol. 2025, 107, 1398–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boecklen, W.J.; Yarnes, C.T.; Cook, B.A.; James, A.C. On the Use of Stable Isotopes in Trophic Ecology. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2011, 42, 411–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, M.J.; McDonald, R.A.; van Veen, F.J.F.; Kelly, S.D.; Rees, G.; Bearhop, S. Application of Nitrogen and Carbon Stable Isotopes (δ15N and δ13C) to Quantify Food Chain Length and Trophic Structure. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e93281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, B.J.; Fry, B. Stable Isotopes in Ecosystem Studies. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1987, 18, 293–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, D.M. Using Stable Isotopes to Estimate Trophic Position: Models, Methods, and Assumptions. Ecology 2002, 83, 703–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsome, S.D.; Martinez del Rio, C.; Bearhop, S.; Phillips, D.L. A Niche for Isotopic Ecology. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2007, 5, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulvy, N.K.; Fowler, S.L.; Musick, J.A.; Cavanagh, R.D.; Kyne, P.M.; Harrison, L.R.; Carlson, J.K.; Davidson, L.N.; Fordham, S.V.; Francis, M.P.; et al. Extinction Risk and Conservation of the World’s Sharks and Rays. eLife 2014, 3, e00590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelsleichter, J.; Sparkman, G.; Howey, L.A.; Brooks, E.J.; Shipley, O.N. Elevated Accumulation of the Toxic Metal Mercury in the Critically Endangered Oceanic Whitetip Shark Carcharhinus Longimanus from the Northwestern Atlantic Ocean. Endanger. Species Res. 2020, 43, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacoureau, N.; Rigby, C.L.; Kyne, P.M.; Sherley, R.B.; Winker, H.; Carlson, J.K.; Fordham, S.V.; Barreto, R.; Fernando, D.; Francis, M.P.; et al. Half a Century of Global Decline in Oceanic Sharks and Rays. Nature 2021, 589, 567–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braune, B.M.; Outridge, P.M.; Fisk, A.T.; Muir, D.C.G.; Helm, P.A.; Hobbs, K.; Hoekstra, P.F.; Kuzyk, Z.A.; Kwan, M.; Letcher, R.J.; et al. Persistent Organic Pollutants and Mercury in Marine Biota of the Canadian Arctic: An Overview of Spatial and Temporal Trends. Sci. Total Environ. 2005, 351–352, 4–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storelli, M.M.; Storelli, A.; Marcotrigiano, G.O. Concentrations and Hazard Assessment of Polychlorinated Biphenyls and Organochlorine Pesticides in Shark Liver from the Mediterranean Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2005, 50, 850–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, M.F.; Lacerda, L.D.; Lai, C.-T. Trace Metals and Persistent Organic Pollutants Contamination in Batoids (Chondrichthyes: Batoidea): A Systematic Review. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 248, 684–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consales, G.; Marsili, L. Assessment of the Conservation Status of Chondrichthyans: Underestimation of the Pollution Threat. Eur. Zool. J. 2021, 88, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consales, G.; Bottaro, M.; Mancusi, C.; Neri, A.; Sartor, P.; Voliani, A.; D’Agostino, A.; Marsili, L. Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) in Three Bathyal Chondrichthyes from the North-Western Mediterranean Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 196, 115647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gračan, R.; Polak, T.; Lazar, B. Life History Traits of the Blackspotted Smooth-Hound Mustelus Punctulatus (Carcharhiniformes: Triakidae) in the Adriatic Sea. Nat. Croat. 2021, 30, 475–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colloca, F.; Enea, M.; Ragonese, S.; Di Lorenzo, M. A Century of Fishery Data Documenting the Collapse of Smooth-Hounds (Mustelus Spp.) in the Mediterranean Sea. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2017, 27, 1145–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, M.; Vizzini, S.; Signa, G.; Andolina, C.; Boscolo Palo, G.; Gristina, M.; Mazzoldi, C.; Colloca, F. Ontogenetic Trophic Segregation between Two Threatened Smooth-Hound Sharks in the Central Mediterranean Sea. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riginella, E.; Correale, V.; Marino, I.A.M.; Rasotto, M.B.; Vrbatovic, A.; Zane, L.; Mazzoldi, C. Contrasting Life-History Traits of Two Sympatric Smooth-Hound Species: Implication for Vulnerability. J. Fish Biol. 2020, 96, 853–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barausse, A.; Correale, V.; Curkovic, A.; Finotto, L.; Riginella, E.; Visentin, E.; Mazzoldi, C. The Role of Fisheries and the Environment in Driving the Decline of Elasmobranchs in the Northern Adriatic Sea. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2014, 71, 1593–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanomi, S.; Pulcinella, J.; Fortuna, C.M.; Moro, F.; Sala, A. Elasmobranch Bycatch in the Italian Adriatic Pelagic Trawl Fishery. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0191647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrell, E.; Dulvy, N.K. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Mustelus Mustelus; IUCN Red List of Threatened Species; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Serena, F. Field Identification Guide to the Sharks and Rays of the Mediterranean and Black Sea; FAO Species Identification Guide for Fishery Purposes; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, W.; Schneider, M.; Bauchot, M.L. Fiches FAO D’identification des Espèces Pour les Besoins de la Pêche (Révision 1); Méditerranée et mer Noire; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1987; Volumes I et II. [Google Scholar]

- Ballschmiter, K.; Zell, M. Analysis of Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCB) by Glass Capillary Gas Chromatography. Z. Anal. Chem. 1980, 302, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeghnoun, A.; Pascal, M.; Fréry, N.; Sarter, H.; Falq, G.; Focant, J.F.; Eppe, G. Dealing with the Non-Detected and Non-Quantified Data. The Example of the Serum Dioxin Data in the French Dioxin and Incinerators Study. Organohalogen Compd. 2007, 69, 2288–2291. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzetti, M.; Marsili, L.; Valsecchi, S.; Roscioli, C.; Polesello, S.; Altemura, P.; Voliani, A.; Mancusi, C. First Investigation of Per-and Poly Fluoroalkylsubstances (PFAS) in Striped Dolphin Stenella Coeruleoalba Stranded along Tuscany Coast (North Western Mediterranean Sea). In Ninth International Symposium “Monitoring of Mediterranean Coastal Areas: Problems and Measurement Techniques”; Bonora, L., Carboni, D., De Vincenzi, M., Matteucci, G., Eds.; Firenze University Press: Florence, Italy, 2022; pp. 729–737. ISBN 979-12-215-0030-1. [Google Scholar]

- Fry, B.; Brand, W.; Mersch, F.J.; Tholke, K.; Garritt, R. Automated Analysis System for Coupled .Delta.13C and .Delta.15N Measurements. Anal. Chem. 1992, 64, 288–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USEPA U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. USEPA Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS) on p,p-Dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 1999.

- USEPA U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS) on Aroclor 1254; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 1999.

- USEPA U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. USEPA Guidelines for Carcinogen Risk Assessment; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; p. 166.

- Jiang, Q.T.; Lee, T.K.M.; Chen, K.; Wong, H.L.; Zheng, J.S.; Giesy, J.P.; Lo, K.K.W.; Yamashita, N.; Lam, P.K.S. Human Health Risk Assessment of Organochlorines Associated with Fish Consumption in a Coastal City in China. Environ. Pollut. 2005, 136, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, A.; Borrell, A.; Pastor, T. Biological Factors Affecting Variability of Persistent Pollutant Levels in Cetaceans. J. Cetacean Res. Manag. 1999, 83–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amodio, E.; Turci, R.; Massenti, M.F.; Di Gaudio, F.; Minoia, C.; Vitale, F.; Firenze, A.; Calamusa, G. Serum Concentrations of Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) in the Inhabitants of a Sicilian City. Chemosphere 2012, 89, 970–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilar, A. Relationship of DDE/ΣDDT in Marine Mammals to the Chronology of DDT Input into the Ecosystem. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1984, 41, 840–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinčić, D.; Herceg Romanić, S.; Kljaković-Gašpić, Z.; Tičina, V. Legacy Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) in Archive Samples of Wild Bluefin Tuna from the Mediterranean Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 155, 111086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsydenova, O.; Minh, T.B.; Kajiwara, N.; Batoev, V.; Tanabe, S. Recent Contamination by Persistent Organochlorines in Baikal Seal (Phoca Sibirica) from Lake Baikal, Russia. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2004, 48, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowell, L.H.; Capel, P.D.; Dileanis, P.D. Pesticides in Stream Sediment and Aquatic Biota; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1999; ISBN 978-0-429-10443-5. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, X.; Zhu, T. Using the o,P′-DDT/p,P′-DDT Ratio to Identify DDT Sources in China. Chemosphere 2010, 81, 1033–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsolini, S.; Focardi, S.; Kannan, K.; Tanabe, S.; Borrell, A.; Tatsukawa, R. Congener Profile and Toxicity Assessment of Polychlorinated Biphenyls in Dolphins, Sharks and Tuna Collected from Italian Coastal Waters. Mar. Environ. Res. 1995, 40, 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storelli, M.M.; Marcotrigiano, G.O. Persistent Organochlorine Residues and Toxic Evaluation of Polychlorinated Biphenyls in Sharks from the Mediterranean Sea (Italy). Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2001, 42, 1323–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdi, Q.; Griffin, E.K.; Esplugas, J.; Gelsleichter, J.; Galloway, A.S.; Frazier, B.S.; Timshina, A.S.; Grubbs, R.D.; Correia, K.; Camacho, C.G.; et al. Species-Specific Profiles of per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in Small Coastal Sharks along the South Atlantic Bight of the United States. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 927, 171758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marciano, J.; Crawford, L.; Mukhopadhyay, L.; Scott, W.; McElroy, A.; McDonough, C. Per/Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) in a Marine Apex Predator (White Shark, Carcharodon carcharias) in the Northwest Atlantic Ocean. ACS Environ. Au 2024, 4, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlisle, A.B.; Kim, S.L.; Semmens, B.X.; Madigan, D.J.; Jorgensen, S.J.; Perle, C.R.; Anderson, S.D.; Chapple, T.K.; Kanive, P.E.; Block, B.A. Using Stable Isotope Analysis to Understand the Migration and Trophic Ecology of Northeastern Pacific White Sharks (Carcharodon carcharias). PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e30492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobson, K.A. Tracing Origins and Migration of Wildlife Using Stable Isotopes: A Review. Oecologia 1999, 120, 314–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobson, K.A.; Piatt, J.F.; Pitocchelli, J. Using Stable Isotopes to Determine Seabird Trophic Relationships. J. Anim. Ecol. 1994, 63, 786–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Document 32011R1259; European Union Commission Regulation (EU) No 1259/2011 of 2 December 2011 Amending Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006 as Regards Maximum Levels for Dioxins, Dioxin-Like PCBs and Non Dioxin-like PCBs in foodstuffsText with EEA Relevance. European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2011; p. 6.

- Document 32023R0915; European Union Commission Regulation (EU) 2023/915 Maximum Levels for Certain Contaminants in Food and Repealing Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006. European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2023; p. 55.

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Results of the Monitoring of Non Dioxin-Like PCBs in Food and Feed; European Food Safety Authority: Parma, Italy, 2010; p. 35. [Google Scholar]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Results of the Monitoring of Non Dioxin-like PCBs in Food and Feed. EFSA J. 2010, 8, 1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camhi, M. Sharks and Their Relatives: Ecology and Conservation; IUCN Publications Services Unit: Gland, Switzerland; IUCN Publications Services Unit: Cambridge, UK, 1998; ISBN 978-2-8317-0460-9. [Google Scholar]

- Schleiffer, M.; Speiser, B. Presence of Pesticides in the Environment, Transition into Organic Food, and Implications for Quality Assurance along the European Organic Food Chain—A Review. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 313, 120116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agostino, F.; Bellante, A.; Quinci, E.; Gherardi, S.; Placenti, F.; Sabatino, N.; Buffa, G.; Avellone, G.; Di Stefano, V.; Del Core, M. Persistent and Emerging Organic Pollutants in the Marine Coastal Environment of the Gulf of Milazzo (Southern Italy): Human Health Risk Assessment. Front. Environ. Sci. 2020, 8, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merhaby, D.; Rabodonirina, S.; Net, S.; Ouddane, B.; Halwani, J. Overview of Sediments Pollution by PAHs and PCBs in Mediterranean Basin: Transport, Fate, Occurrence, and Distribution. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 149, 110646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbato, M.; Barría, C.; Bellodi, A.; Bonanomi, S.; Borme, D.; Ćetković, I.; Colloca, F.; Colmenero, A.I.; Crocetta, F.; De Carlo, F.; et al. The Use of Fishers’ Local Ecological Knowledge to Reconstruct Fish Behavioural Traits and Fishers’ Perception of Conservation Relevance of Elasmobranchs in the Mediterranean Sea. Medit. Mar. Sci. 2021, 22, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Corredor, E.; Ouled-Cheikh, J.; Navarro, J.; Coll, M. An Overview of the Ecological Roles of Mediterranean Chondrichthyans through Extinction Scenarios. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2024, 34, 421–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, A.C.; O’Neill, B.; Sigge, G.O.; Kerwath, S.E.; Hoffman, L.C. Heavy Metals in Marine Fish Meat and Consumer Health: A Review. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Tissue | HCB | PCBs | DDTs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mustelus mustelus | Liver n = 28 | 13.19 ± 5.24 (2.66–24.84) | 3150.16 ± 2280.20 (348.16–9467.97) | 946.13 ± 667.69 (149.25–3007.75) | 0.32 ± 0.07 (0.21–0.48) | 9.73 ± 3.30 (5.40–21.31) | 0.81 ± 0.05 (0.67–0.89) | 0.07 ± 0.04 (0.02–0.18) |

| Muscle n = 28 | 1.75 ± 1.60 (0.28–7.58) | 254.94 ± 170.78 (76.15–845.51) | 76.50 ± 58.14 (21.61–253.98) | 0.31 ± 0.07 (0.08–0.42) | 10.70 ± 7.02 (3.47–42.45) | 0.57 ± 0.12 (0.23–0.76) | 0.29 ± 0.11 (0.13–0.57) | |

| Mustelus punctulatus | Liver n = 43 | 11.20 ± 4.34 (2.76–25.21) | 2373.74 ± 2047.37 (291.78–9251.41) | 726.9 ± 496.26 (82.85–2005.75) | 0.34 ± 0.09 (0.18–0.64) | 37.61 ± 119.78 (3.09–794.62) | 0.82 ± 0.06 (0.59–0.94) | 0.07 ± 0.03 (0.02–0.17) |

| Muscle n = 43 | 2.04 ± 4.33 (0.32–28.40) | 316.20 ± 458.88 (44.97–2633.84) | 94.38 ± 102.26 (21.58–615.51) | 0.38 ± 0.14 (0.13–0.71) | 11.07 ± 11.25 (0.34–73.24) | 0.60 ± 0.18 (0.04–0.85) | 0.25 ± 0.12 (0.10–0.60) |

| Species | OC Group | Tissue | HR Non-CR | HR CR | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mustelus mustelus | PCBs | Muscle | 0.0943 | 0.0785 | |

| Liver | 5.7211 | 4.7637 | |||

| DDTs | Muscle | 0.0001 | 0.0004 | ||

| Liver | 0.0067 | 0.0237 | |||

| Mustelus punctulatus | PCBs | Muscle | 0.1136 | 0.0946 | |

| Liver | 4.7032 | 3.9162 | |||

| DDTs | Muscle | 0.0002 | 0.0006 | ||

| Liver | 0.0055 | 0.0193 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Minoia, L.; Consales, G.; Dallai, L.; Di Marcantonio, E.; Mazzetti, M.; Mancusi, C.; Pierro, L.; Riginella, E.; Sinopoli, M.; Bottaro, M.; et al. Trophic Drivers of Organochlorine and PFAS Accumulation in Mediterranean Smooth-Hound Sharks: Insights from Stable Isotopes and Human Health Risk. Toxics 2026, 14, 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010058

Minoia L, Consales G, Dallai L, Di Marcantonio E, Mazzetti M, Mancusi C, Pierro L, Riginella E, Sinopoli M, Bottaro M, et al. Trophic Drivers of Organochlorine and PFAS Accumulation in Mediterranean Smooth-Hound Sharks: Insights from Stable Isotopes and Human Health Risk. Toxics. 2026; 14(1):58. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010058

Chicago/Turabian StyleMinoia, Lorenzo, Guia Consales, Luigi Dallai, Eduardo Di Marcantonio, Michele Mazzetti, Cecilia Mancusi, Lucia Pierro, Emilio Riginella, Mauro Sinopoli, Massimiliano Bottaro, and et al. 2026. "Trophic Drivers of Organochlorine and PFAS Accumulation in Mediterranean Smooth-Hound Sharks: Insights from Stable Isotopes and Human Health Risk" Toxics 14, no. 1: 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010058

APA StyleMinoia, L., Consales, G., Dallai, L., Di Marcantonio, E., Mazzetti, M., Mancusi, C., Pierro, L., Riginella, E., Sinopoli, M., Bottaro, M., & Marsili, L. (2026). Trophic Drivers of Organochlorine and PFAS Accumulation in Mediterranean Smooth-Hound Sharks: Insights from Stable Isotopes and Human Health Risk. Toxics, 14(1), 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010058