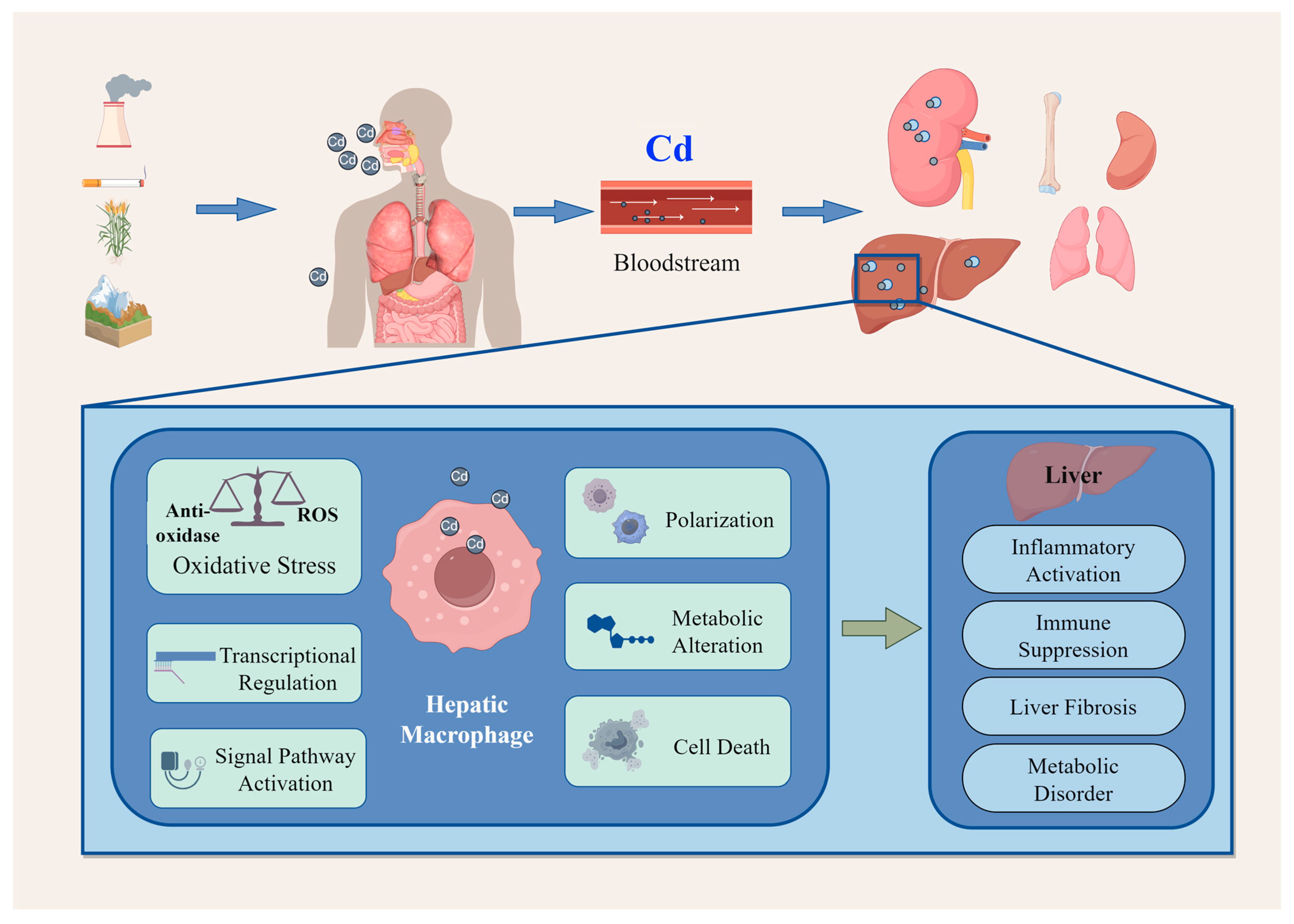

Research Advances on Cadmium-Induced Toxicity in Hepatic Macrophages

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Effects of Cadmium on Hepatic Macrophages

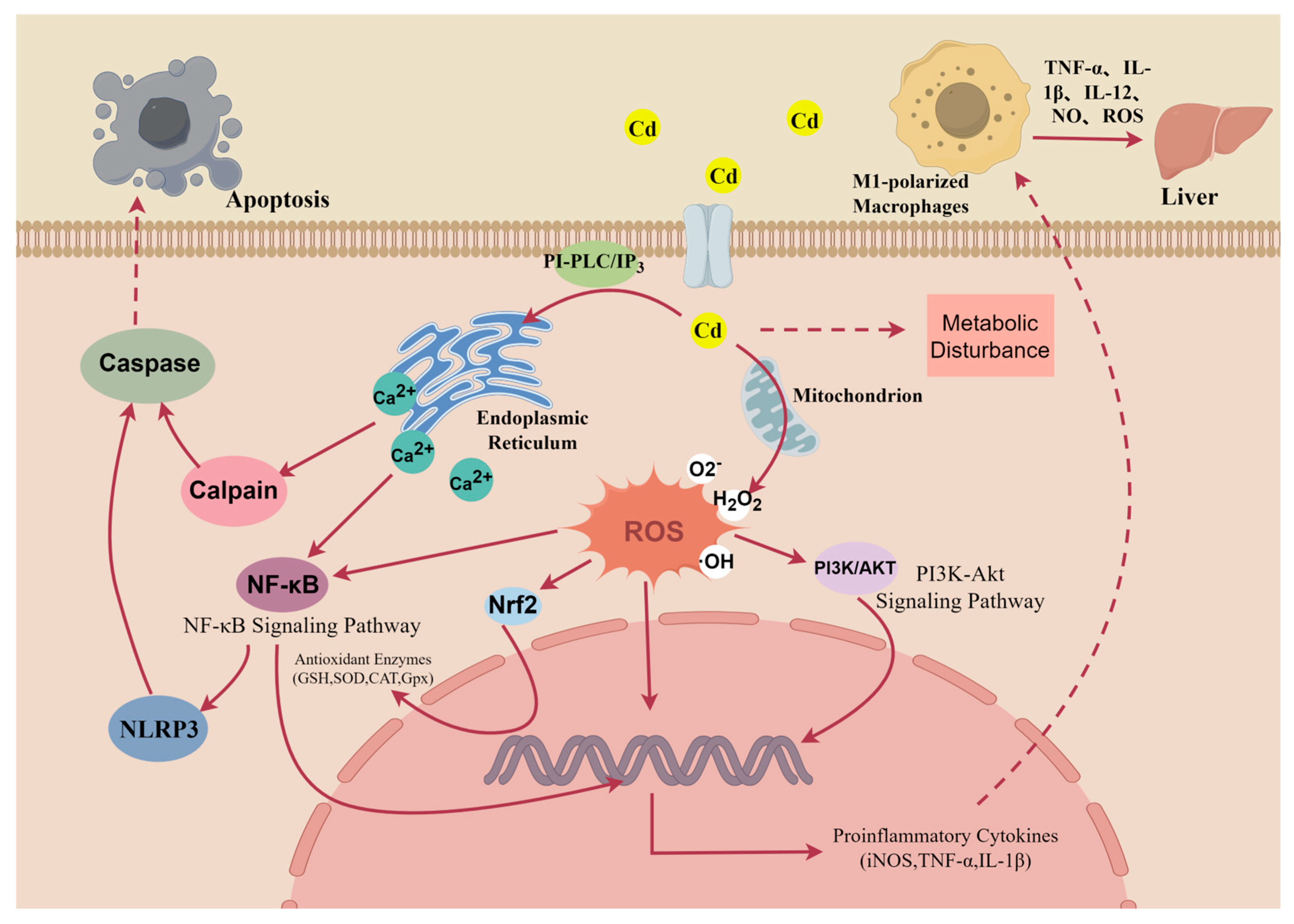

2.1. Oxidative Stress in Macrophages

2.2. Alterations in Gene Transcription

2.3. Dysregulation of Signaling Pathways

| Chemical Forms of Cd | Dose | Hepatic Macrophages | Source Species | Signaling Pathways | Toxic Effect | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CdTe | 5–50 nM | KUP5 cells | Mice | NF-κB signaling pathway | NLRP3 inflammasome expression; Pro-inflammatory cytokine expression | [26] |

| CdCl2 | 20 mg/kg | Hepatic macrophages | Pigs | PI3K/AKT pathway | M1 polarization; Pro-inflammatory cytokine expression | [53] |

| CdTe | 1 μM | RAW264.7 cells | Mice | Nrf2 pathway inhibition | Pro-inflammatory cytokine expression; Mitophagy; Ferroptosis | [42,43] |

| CdCl2 | 140 mg/kg | KCs | Chicks | APJ-AMPK-PGC1α | activate astrocytes and more hepatic fibrosis | [54] |

| CdCl2 | 0.1–1 μM | Thioglycollate-elicited macrophages | Mice | MAPK pathway | Promotion of macrophage proliferation | [50] |

| CdCl2 | 20, 100, 500 μM | J774A.1 murine macrophage cells | Mice | JNK-caspase-3 pathway | Macrophage apoptosis; Growth arrest; Mitochondrial impairment | [55] |

2.4. Alterations in Metabolic Pathways

2.5. Alterations in Cellular Polarization

2.6. Macrophage Death

3. Hepatic Impact of Cadmium-Induced Macrophage Toxicity

4. Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Qu, F.; Zheng, W. Cadmium Exposure: Mechanisms and Pathways of Toxicity and Implications for Human Health. Toxics 2024, 12, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Chen, Z.; Song, W.; Hong, D.; Huang, L.; Li, Y. A review on Cadmium Exposure in the Population and Intervention Strategies Against Cadmium Toxicity. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2021, 106, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Reynolds, M. Cadmium exposure in living organisms: A short review. Sci. Total. Environ. 2019, 678, 761–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, K.; Levänen, B.; Palmberg, L.; Åkesson, A.; Lindén, A. Cadmium in tobacco smokers: A neglected link to lung disease? Eur. Respir. Rev. 2018, 27, 170122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smereczański, N.M.; Brzóska, M.M. Current Levels of Environmental Exposure to Cadmium in Industrialized Countries as a Risk Factor for Kidney Damage in the General Population: A Comprehensive Review of Available Data. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chavatte, L.; Juan, M.; Mounicou, S.; Noblesse, E.L.; Pays, K.; Nizard, C.; Bulteau, A.-L. Elemental and molecular imaging of human full thickness skin after exposure to heavy metals. Metallomics 2020, 12, 1555–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Sung, G.-H.; Lee, S.; Han, K.J.; Han, H.-J. Serum cadmium is associated with hepatic steatosis and fibrosis: Korean national health and nutrition examination survey data IV-VII. Medicine 2022, 101, e28559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, K.; Xu, J.; Xu, Y.; Wang, C.; Yu, J. The association between endocrine disrupting chemicals and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 205, 107251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Shi, Z.; Hu, H.; Shen, D.; Zhou, Y.; Feng, Y.; Tang, D.; Qin, H.; Wang, J. The relationship between cadmium exposure and hepatitis B susceptibility and the establishment of its prediction model. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 95801–95809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Jian, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, Y.; Ge, Y.; Wang, H.; Mu, W. Molecular regulatory networks of microplastics and cadmium mediated hepatotoxicity from NAFLD to tumorigenesis via integrated approaches. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 300, 118431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyder, O.; Chung, M.; Cosgrove, D.; Herman, J.M.; Li, Z.; Firoozmand, A.; Gurakar, A.; Koteish, A.; Pawlik, T.M. Cadmium exposure and liver disease among US adults. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2013, 17, 1265–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, N.K.; Mann, K.K. Mechanisms of Metal-Induced Hepatic Inflammation. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2024, 11, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Ge, X.; Xu, J.; Li, A.; Mei, Y.; Yin, G.; Wu, J.; Liu, X.; Wei, L.; Xu, Q. Association between urine metals and liver function biomarkers in Northeast China: A cross-sectional study. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 231, 113163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arab, H.H.; Ashour, A.M.; Eid, A.H.; Arafa, E.-S.A.; Al Khabbaz, H.J.; El-Aal, S.A.A. Targeting oxidative stress, apoptosis, and autophagy by galangin mitigates cadmium-induced renal damage: Role of SIRT1/Nrf2 and AMPK/mTOR pathways. Life Sci. 2022, 291, 120300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, H.; Liu, X.; Liu, Z. Oxidative stress and Ca2+ signals involved on cadmium-induced apoptosis in rat hepatocyte. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2014, 161, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Huang, L.; Sun, L.; Deng, Q. Alleviative Effect of Threonine on Cadmium-Induced Liver Injury in Mice. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2023, 201, 4437–4446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treviño, S.; Andrade-García, A.; Camacho, I.H.; León-Chavez, B.A.; Aguilar-Alonso, P.; Flores, G.; Brambila, E. Chronic Cadmium Exposure Lead to Inhibition of Serum and Hepatic Alkaline Phosphatase Activity in Wistar Rats. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2015, 29, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzirogiannis, K.N.; Panoutsopoulos, G.I.; Demonakou, M.D.; Hereti, R.I.; Alexandropoulou, K.N.; Basayannis, A.C.; Mykoniatis, M.G. Time-course of cadmium-induced acute hepatotoxicity in the rat liver: The role of apoptosis. Arch. Toxicol. 2003, 77, 694–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamanoa, T.; DeCicco, L.A.; Rikans, L.E. Attenuation of cadmium-induced liver injury in senescent male fischer 344 rats: Role of Kupffer cells and inflammatory cytokines. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2000, 162, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheu, K.M.; Hoffmann, A. Functional Hallmarks of Healthy Macrophage Responses: Their Regulatory Basis and Disease Relevance. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2022, 40, 295–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Lambrecht, J.; Ju, C.; Tacke, F. Hepatic macrophages in liver homeostasis and diseases-diversity, plasticity and therapeutic opportunities. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2021, 18, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillot, A.; Tacke, F. Liver Macrophages: Old Dogmas and New Insights. Hepatol. Commun. 2019, 3, 730–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Qiu, J.; Zou, S.; Tan, L.; Miao, T. The role of macrophages in liver fibrosis: Composition, heterogeneity, and therapeutic strategies. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1494250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamate, J.; Izawa, T.; Kuwamura, M. Macrophage pathology in hepatotoxicity. J. Toxicol. Pathol. 2023, 36, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, A.; Kumar, A.; Lal, A.; Pant, M. Cellular mechanisms of cadmium-induced toxicity: A review. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2014, 24, 378–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Wu, D.; Ma, Y.; Cao, Y.; Liu, Q.; Tang, M.; Pu, Y.; Zhang, T. Reactive oxygen species trigger NF-κB-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome activation involvement in low-dose CdTe QDs exposure-induced hepatotoxicity. Redox Biol. 2021, 47, 102157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Baiyun, R.; Lv, Z.; Li, J.; Han, D.; Zhao, W.; Yu, L.; Deng, N.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Z. Exploring the kidney hazard of exposure to mercuric chloride in mice:Disorder of mitochondrial dynamics induces oxidative stress and results in apoptosis. Chemosphere 2019, 234, 822–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, X.; Fu, M.; Bi, R.; Zheng, X.; Fu, B.; Tian, S.; Liu, C.; Li, Q.; Liu, J. Cadmium induced BEAS-2B cells apoptosis and mitochondria damage via MAPK signaling pathway. Chemosphere 2020, 263, 128346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzengue, Y.; Candéias, S.M.; Sauvaigo, S.; Douki, T.; Favier, A.; Rachidi, W.; Guiraud, P. The toxicity redox mechanisms of cadmium alone or together with copper and zinc homeostasis alteration: Its redox biomarkers. J. Trace Elements Med. Biol. 2011, 25, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Mendoza, D.; Han, B.; Berg, H.J.v.D.; Brink, N.W.v.D. Cell-specific immune-modulation of cadmium on murine macrophages and mast cell lines in vitro. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2019, 39, 992–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matović, V.; Buha, A.; Ðukić-Ćosić, D.; Bulat, Z. Insight into the oxidative stress induced by lead and/or cadmium in blood, liver and kidneys. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2015, 78, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djukić-Cosić, D.; Curcić Jovanović, M.; Plamenac Bulat, Z.; Ninković, M.; Malicević, Z.; Matović, V. Relation between lipid peroxidation and iron concentration in mouse liver after acute and subacute cadmium intoxication. J. Trace Elements Med. Biol. 2008, 22, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donatella, C.; Antonella, C.; Zhichao, C.; Angelo, Z.; Ciriaco, C.; Serenella, M. Ferroptosis and Senescence: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhang, S.; He, R.; Wu, Y.; Chen, G.; Fu, Z. Cadmium exposure to murine macrophages decreases their inflammatory responses and increases their oxidative stress. Chemosphere 2016, 144, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, H.; Cai, D.; Li, P.; Jin, J.; Jiang, X.; Li, Z.; Tian, L.; Chen, G.; Sun, J.; et al. Chronic oral exposure to cadmium causes liver inflammation by NLRP3 inflammasome activation in pubertal mice. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2021, 148, 111944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, T.; Wing-Kee, L. Cadmium and cellular signaling cascades: Interactions between cell death and survival pathways. Arch. Toxicol. 2013, 87, 1743–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M.J.; Liu, Z.-G. Crosstalk of reactive oxygen species and NF-κB signaling. Cell Res. 2011, 21, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brigelius-Flohé, R.; Flohé, L. Basic principles and emerging concepts in the redox control of transcription factors. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011, 15, 2335–2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidova, S.; Milushev, V.; Satchanska, G. The Mechanisms of Cadmium Toxicity in Living Organisms. Toxics 2024, 12, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Han, X.; Xu, N.; Shen, W.; Wang, G.; Jiao, J.; Kong, W.; Yu, J.; Fu, J.; Pi, J. Nrf2 deficiency aggravates hepatic cadmium accumulation, inflammatory response and subsequent injury induced by chronic cadmium exposure in mice. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2025, 497, 117263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Liu, J.; Liu, J.; Fatima, M.; Yang, L.; Qin, Y.; Li, W.; Sun, Z.; Yang, B. Exercise antagonizes cadmium-caused liver and intestinal injury in mice via Nrf2 and TLR2/NF-κB signalling pathway. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 294, 118100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, N.; Liang, Y.; Wei, T.; Zou, L.; Huang, X.; Kong, L.; Tang, M.; Zhang, T. The role of ferroptosis mediated by NRF2/ERK-regulated ferritinophagy in CdTe QDs-induced inflammation in macrophage. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 436, 129043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Liang, Y.; Wei, T.; Huang, X.; Zhang, T.; Tang, M. ROS-mediated NRF2/p-ERK1/2 signaling-involved mitophagy contributes to macrophages activation induced by CdTe quantum dots. Toxicology 2024, 505, 153825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chohelee, C.; Ritwik, M.; Rajeev, K.; Bishal, D.; Mahuya, S. Cadmium induced oxystress alters Nrf2-Keap1 signaling and triggers apoptosis in piscine head kidney macrophages. Aquat. Toxicol. 2021, 231, 105739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wu, J.; Dong, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, G.; Chen, C.; Wang, H.; Yang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Yang, M.; et al. Prolonged Cadmium Exposure and Osteoclastogenesis: A Mechanistic Mouse and in Vitro Study. Environ. Health Perspect. 2024, 132, 67009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horiguchi, H.; Oguma, E. Acute exposure to cadmium induces prolonged neutrophilia along with delayed induction of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in the livers of mice. Arch. Toxicol. 2016, 90, 3005–3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alina-Andreea, Z.; Vlad, S.; Eugen, G.; Crina, S.; Gina, M.; Stefan, S.; Ioana, B.-N. Biological and molecular modifications induced by cadmium and arsenic during breast and prostate cancer development. Environ. Res. 2019, 178, 108700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed Amer, M.; Benoit, S.; Abdulkader, A.; Daliya, K.; Sarah, M.; Eva, H.; Els, L.; Leen, A.; Karen, D.V.; Isabelle, S.; et al. Infection history imprints prolonged changes to the epigenome, transcriptome and function of Kupffer cells. J. Hepatol. 2024, 81, 1023–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keum-Young, S.; Byung-Hoon, L.; Seon-Hee, O. The critical role of autophagy in cadmium-induced immunosuppression regulated by endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated calpain activation in RAW264.7 mouse monocytes. Toxicology 2017, 393, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, U.K.; Gawdi, G.; Akabani, G.; Pizzo, S.V. Cadmium-induced DNA synthesis and cell proliferation in macrophages: The role of intracellular calcium and signal transduction mechanisms. Cell. Signal. 2002, 14, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakamoto, K.; Iwasaki, K.; Sugiyama, H.; Tsuji, Y. Role of the tumor suppressor PTEN in antioxidant responsive element-mediated transcription and associated histone modifications. Mol. Biol. Cell 2009, 20, 1606–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.-Y.; Xia, M.-Z.; Wang, H.; Liu, X.-J.; Hu, Y.-F.; Chen, Y.-H.; Zhang, C.; Xu, D.-X. Cadmium selectively induces MIP-2 and COX-2 through PTEN-mediated Akt activation in RAW264.7 cells. Toxicol. Sci. 2014, 138, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Zhou, S.; Wang, Y.; Shi, X.; Liu, H. Cadmium exposure activates the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway through miRNA-21, induces an increase in M1 polarization of macrophages, and leads to fibrosis of pig liver tissue. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 228, 113015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.-H.; Lv, M.-W.; Zhao, Y.-X.; Zhang, H.; Saleem, M.A.U.; Zhao, Y.; Li, J.-L. Nano-Selenium Antagonized Cadmium-Induced Liver Fibrosis in Chicken. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 71, 846–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Sharma, R.P. Calcium-mediated activation of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) and apoptosis in response to cadmium in murine macrophages. Toxicol. Sci. 2004, 81, 518–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zheng, S.; Wang, S.; Liu, H.; Xu, S. Subacute cadmium exposure promotes M1 macrophage polarization through oxidative stress-evoked inflammatory response and induces porcine adrenal fibrosis. Toxicology 2021, 461, 152899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, W.; Xiong, Z.; Shu, K.; Sun, M.; Jiang, Y.; Li, L. Glycolysis drives STING signaling to promote M1-macrophage polarization and aggravate liver fibrosis. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2025, 21, 6411–6429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Ong, M.; Yi, X.; Xing, M.; Tian, X.; Zhang, K.; Lu, L.; Wang, H.; Lin, X.; Fang, J.; et al. F13A1-Mediated Macrophage Activation Promotes MASH Progression via the PKM2/HIF1A Pathway. Adv. Sci. 2025, e18128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson-Casey, J.L.; Gu, L.; Fiehn, O.; Carter, A.B. Cadmium-mediated lung injury is exacerbated by the persistence of classically activated macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 15754–15766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olszowski, T.; Gutowska, I.; Baranowska-Bosiacka, I.; Łukomska, A.; Drozd, A.; Chlubek, D. Cadmium Alters the Concentration of Fatty Acids in THP-1 Macrophages. Biol. Trace Element Res. 2018, 182, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumkova, J.; Vrlikova, L.; Vecera, Z.; Putnova, B.; Docekal, B.; Mikuska, P.; Fictum, P.; Hampl, A.; Buchtova, M. Inhaled Cadmium Oxide Nanoparticles: Their in Vivo Fate and Effect on Target Organs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locati, M.; Curtale, G.; Mantovani, A. Diversity, Mechanisms, and Significance of Macrophage Plasticity. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2020, 15, 123–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapouri-Moghaddam, A.; Mohammadian, S.; Vazini, H.; Taghadosi, M.; Esmaeili, S.-A.; Mardani, F.; Seifi, B.; Mohammadi, A.; Afshari, J.T.; Sahebkar, A. Macrophage plasticity, polarization, and function in health and disease. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018, 233, 6425–6440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahamed, F.; Eppler, N.; Jones, E.; Zhang, Y. Understanding Macrophage Complexity in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: Transitioning from the M1/M2 Paradigm to Spatial Dynamics. Livers 2024, 4, 455–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magee, N.; Ahamed, F.; Eppler, N.; Jones, E.; Ghosh, P.; He, L.; Zhang, Y. Hepatic transcriptome profiling reveals early signatures associated with disease transition from non-alcoholic steatosis to steatohepatitis. Liver Res. 2022, 6, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Luo, J.; Guo, H.; Wang, X.; Hu, Z.; Pu, W.; Chu, X.; Zhang, C. Molybdenum and cadmium co-exposure promotes M1 macrophage polarization through oxidative stress-mediated inflammatory response and induces pulmonary fibrosis in Shaoxing ducks (Anas platyrhyncha). Environ. Toxicol. 2022, 37, 2844–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzoni, G.; Ciccotelli, V.; Masiello, L.; De Ciucis, C.G.; Anfossi, A.G.; Vivaldi, B.; Ledda, M.; Zinellu, S.; Giudici, S.D.; Berio, E.; et al. Cadmium and wild boar: Environmental exposure and immunological impact on macrophages. Toxicol. Rep. 2022, 9, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasuyuki, F.; Jin-Yong, L.; Maki, T.; Masahiko, S. Cadmium renal toxicity via apoptotic pathways. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2012, 35, 1892–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lépine, S.; Allegood, J.C.; Edmonds, Y.; Milstien, S.; Spiegel, S. Autophagy induced by deficiency of sphingosine-1-phosphate phosphohydrolase 1 is switched to apoptosis by calpain-mediated autophagy-related gene 5 (Atg5) cleavage. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 44380–44390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Weinman, S.A. Regulation of Hepatic Inflammation via Macrophage Cell Death. Semin. Liver Dis. 2018, 38, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Tuerxunyiming, M.; Sun, Z.; Zheng, S.-Y.; Liu, Q.-B.; Zhao, Q. Burden of diabetes attributable to dietary cadmium exposure in adolescents and adults in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 102353–102362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwabe, R.F.; Tabas, I.; Pajvani, U.B. Mechanisms of Fibrosis Development in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 1913–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, T.; Ali, W.; Ma, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Gu, J.; Bian, J.; Liu, Z.; Zou, H. Cadmium promotes nonalcoholic fatty liver disease by inhibiting intercellular mitochondrial transfer. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 2023, 28, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarghandian, S.; Azimi-Nezhad, M.; Shabestari, M.M.; Azad, F.J.; Farkhondeh, T.; Bafandeh, F. Effect of chronic exposure to cadmium on serum lipid, lipoprotein and oxidative stress indices in male rats. Interdiscip. Toxicol. 2015, 8, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Chai, X.-X.; Zhou, J.; Shi, M.-J.; Zhao, Y.; Tian, Y.; Wang, X.-M.; Ying, T.-X.; Feng, Q.; et al. Chronic exposure to low-dose cadmium facilitated nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in mice by suppressing fatty acid desaturation. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 233, 113306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Chai, X.-X.; Zhao, Y.; Feng, Q.; Dong, R.; Shi, M.-J.; Zhou, J.; Zhao, Y.; Peng, J.; Tian, Y.; et al. Saturated fatty acids synergizes cadmium to induce macrophages M1 polarization and hepatic inflammation. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 259, 115040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-Y.; Tokumoto, M.; Satoh, M. Molecular Mechanisms of Cadmium-Induced Toxicity and Its Modification. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.-T.; Zhen, J.; Leng, J.-Y.; Cai, L.; Ji, H.-L.; Keller, B.B. Zinc as a countermeasure for cadmium toxicity. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2021, 42, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokumoto, M.; Lee, J.-Y.; Fujiwara, Y.; Satoh, M. Long-Term Exposure to Cadmium Causes Hepatic Iron Deficiency through the Suppression of Iron-Transport-Related Gene Expression in the Proximal Duodenum. Toxics 2023, 11, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujiwara, Y.; Lee, J.-Y.; Banno, H.; Imai, S.; Tokumoto, M.; Hasegawa, T.; Seko, Y.; Nagase, H.; Satoh, M. Cadmium induces iron deficiency anemia through the suppression of iron transport in the duodenum. Toxicol. Lett. 2020, 332, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Boshy, M.; Refaat, B.; Almaimani, R.A.; Abdelghany, A.H.; Ahmad, J.; Idris, S.; Almasmoum, H.; Mahbub, A.A.; Ghaith, M.M.; BaSalamah, M.A. Vitamin D(3) and calcium cosupplementation alleviates cadmium hepatotoxicity in the rat: Enhanced antioxidative and anti-inflammatory actions by remodeling cellular calcium pathways. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2020, 34, e22440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, J.; Yin, H.; Yang, Z.; Tan, M.; Wang, F.; Chen, K.; Zuo, Z.; Shu, G.; Cui, H.; Ouyang, P.; et al. Vitamin E protects against cadmium-induced sub-chronic liver injury associated with the inhibition of oxidative stress and activation of Nrf2 pathway. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 208, 111610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, T.; Ali, W.; Ma, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Gu, J.; Bian, J.; Liu, Z.; Zou, H. Baicalin and N-acetylcysteine regulate choline metabolism via TFAM to attenuate cadmium-induced liver fibrosis. Phytomedicine 2024, 125, 155337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Huang, J.; Wang, J.; Sun, H.; Li, J.; Li, S.; Tang, Y.-E.; Wang, Z.; Song, Q. Effect of glucose selenol on hepatic lipid metabolism disorder induced by heavy metal cadmium in male rats. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2025, 1870, 159589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambade, A.; Lowe, P.; Kodys, K.; Catalano, D.; Gyongyosi, B.; Cho, Y.; Iracheta-Vellve, A.; Adejumo, A.; Saha, B.; Calenda, C.; et al. Pharmacological Inhibition of CCR2/5 Signaling Prevents and Reverses Alcohol-Induced Liver Damage, Steatosis, and Inflammation in Mice. Hepatology 2019, 69, 1105–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krenkel, O.; Puengel, T.; Govaere, O.; Abdallah, A.T.; Mossanen, J.C.; Kohlhepp, M.; Liepelt, A.; Lefebvre, E.; Luedde, T.; Hellerbrand, C.; et al. Therapeutic inhibition of inflammatory monocyte recruitment reduces steatohepatitis and liver fibrosis. Hepatology 2018, 67, 1270–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, W.; Ying, S. Research Advances on Cadmium-Induced Toxicity in Hepatic Macrophages. Toxics 2026, 14, 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010057

Chen J, Wang Z, Li W, Ying S. Research Advances on Cadmium-Induced Toxicity in Hepatic Macrophages. Toxics. 2026; 14(1):57. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010057

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Jiongfei, Zhaoan Wang, Wangying Li, and Shibo Ying. 2026. "Research Advances on Cadmium-Induced Toxicity in Hepatic Macrophages" Toxics 14, no. 1: 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010057

APA StyleChen, J., Wang, Z., Li, W., & Ying, S. (2026). Research Advances on Cadmium-Induced Toxicity in Hepatic Macrophages. Toxics, 14(1), 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics14010057