Assessment of Chromium Contamination in Aquatic Environments near Tannery Industries: A Portuguese Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

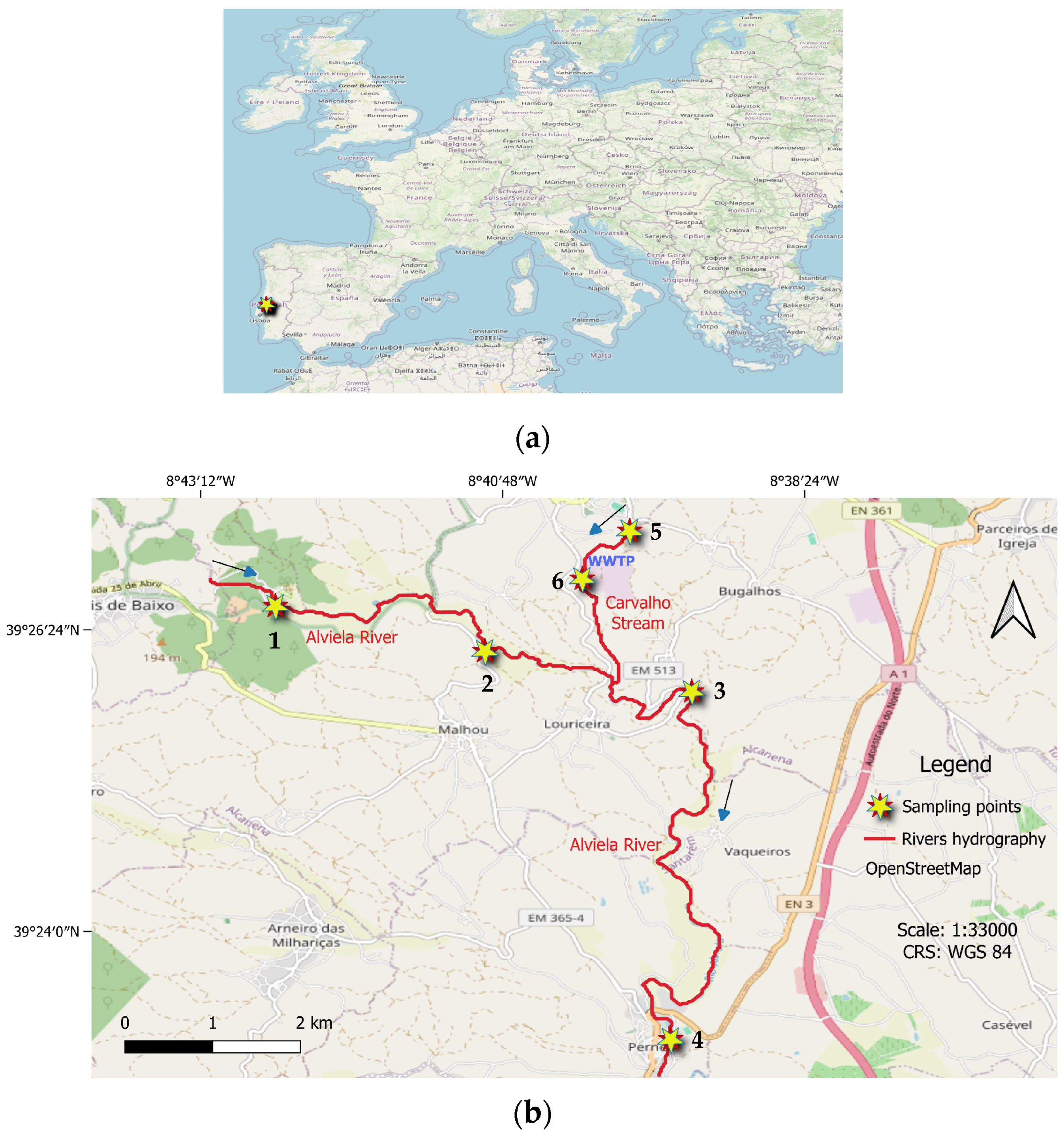

2.1. Sampling Site and Collection

2.2. Sample Treatment and Analysis

2.3. Validation and Quality Control

2.4. Statistical Analysis

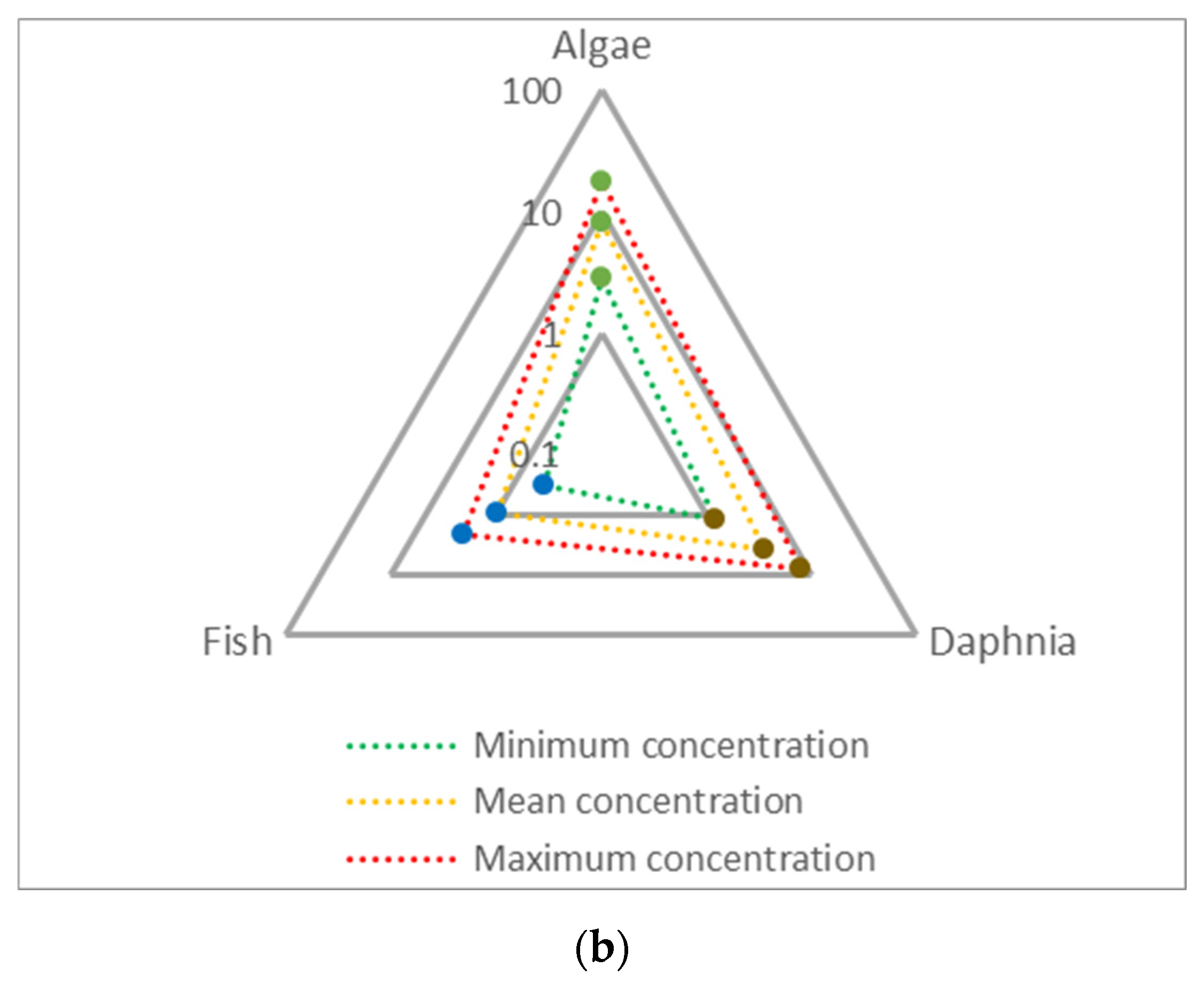

2.5. Environmental Risk Assessment

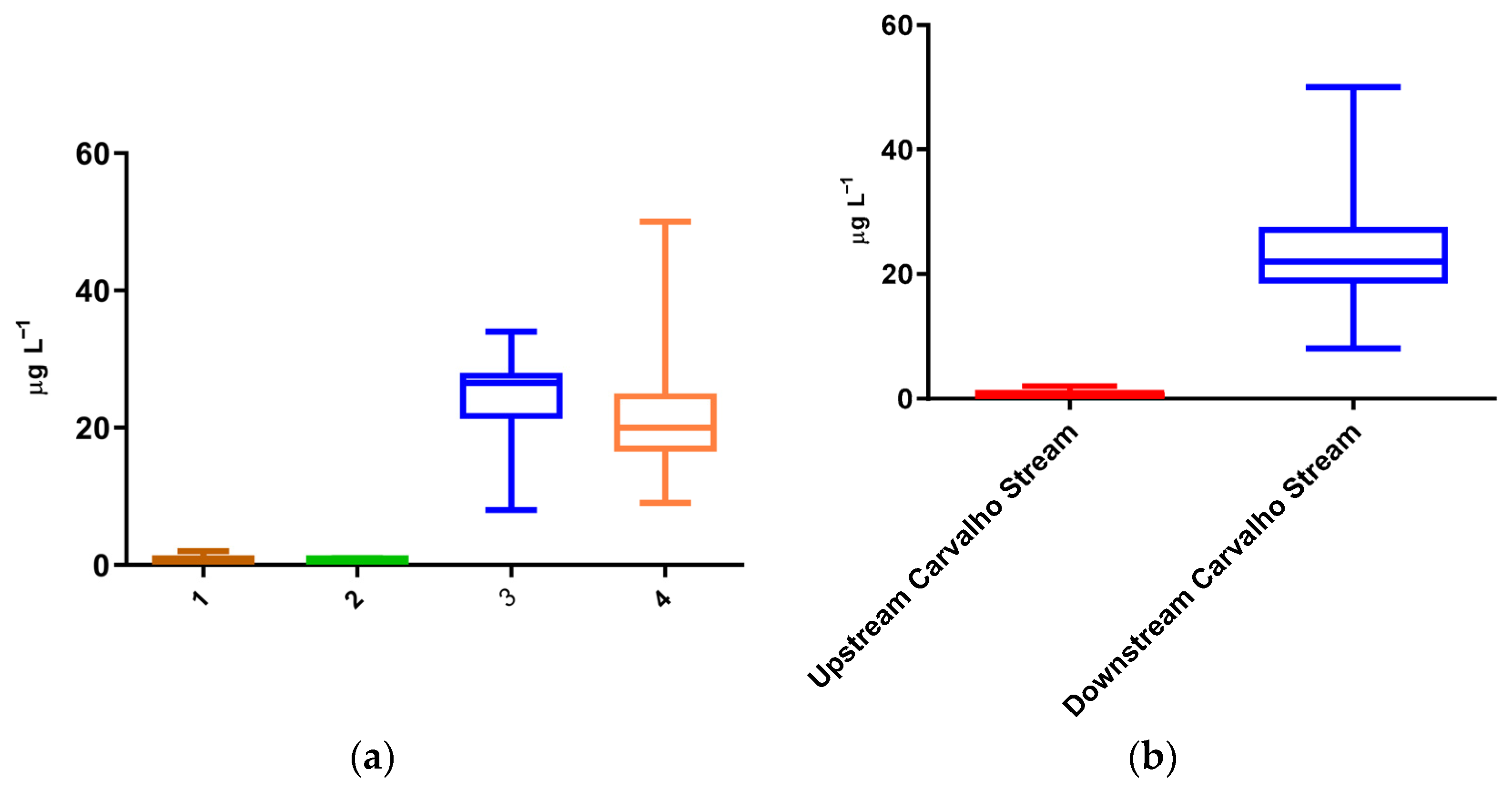

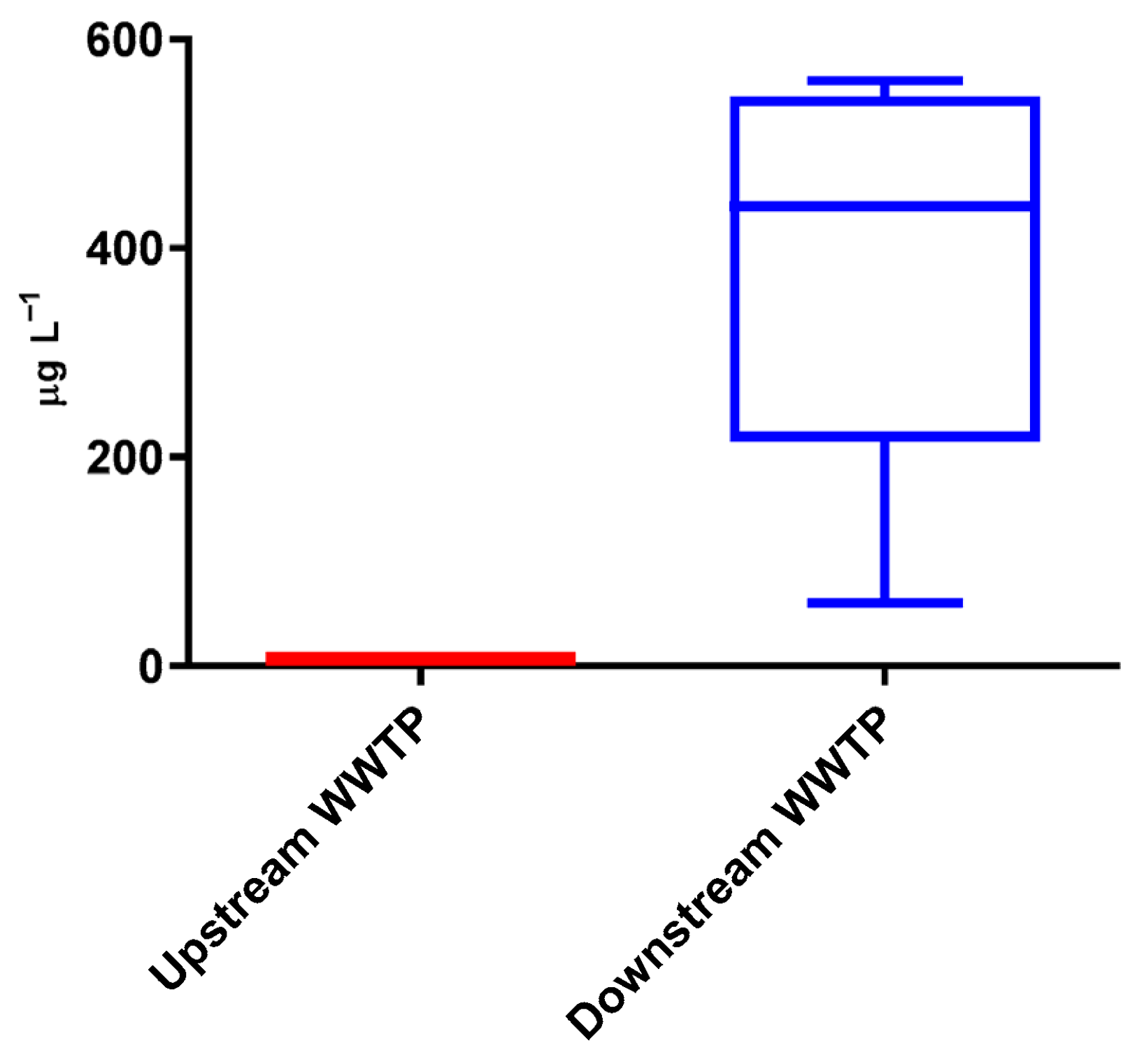

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Frequency and Occurrence

3.2. Environmental and Human Impact

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Cr | Chromium |

| EQS | Environmental quality standards |

| ICP-OES | Inductively coupled plasma coupled with optical emission spectrometry detection |

| ICP-MS | Inductively coupled plasma coupled with spectrometry detection |

| WWTPs | Wastewater treatment plants |

References

- Noyes, P.D.; McElwee, M.K.; Miller, H.D.; Clark, B.W.; Van Tiem, L.A.; Walcott, K.C.; Erwin, K.N.; Levin, E.D. The toxicology of climate change: Environmental contaminants in a warming world. Environ. Int. 2009, 35, 971–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloprogge, J.T.; Ponce, C.P.; Loomis, T. The Periodic Table: Nature’s Building Blocks—An Introduction to the Naturally Occurring Elements, Their Origins and Their Uses; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; ISBN 9780128212790. [Google Scholar]

- Mohanty, S.; Benya, A.; Hota, S.; Kumar, M.S.; Singh, S. Eco-toxicity of hexavalent chromium and its adverse impact on environment and human health in Sukinda Valley of India: A review on pollution and prevention strategies. Environ. Chem. Ecotoxicol. 2023, 5, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgaki, M.-N.; Charalambous, M. Toxic chromium in water and the effects on the human body: A systematic review. J. Water Health 2023, 21, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, R.T.; Bani Mfarrej, M.F.; Alam, P.; Rinklebe, J.; Ahmad, P. Accumulation of chromium in plants and its repercussion in animals and humans. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 301, 119044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tunçeli, A.; Türker, A.R. Determination of palladium in alloy by flame atomic absorption spectrometry after preconcentration of its iodide complex on amberlite XAD-16. Anal. Sci. 2000, 16, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Suleiman, J.S.; He, M.; Hu, B. Chromium(III)-imprinted silica gel for speciation analysis of chromium in environmental water samples with ICP-MS detection. Talanta 2008, 75, 536–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moffat, I.; Martinova, N.; Seidel, C.; Thompson, C.M. Hexavalent Chromium in Drinking Water. J. Am. Water Works Assoc. 2018, 110, E22–E35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhitkovich, A. Chromium in drinking water: Sources, metabolism, and cancer risks. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2011, 24, 1617–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission LIFE Innovative Modified Natural Tannins I’M-TAN. Available online: https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/life/publicWebsite/project/LIFE20-ENV-IT-000759/life-innovative-modified-natural-tannins-im-tan (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Tumolo, M.; Ancona, V.; De Paola, D.; Losacco, D.; Campanale, C.; Massarelli, C.; Uricchio, V.F. Chromium Pollution in European Water, Sources, Health Risk, and Remediation Strategies: An Overview. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nur-E-Alam, M.; Mia, M.A.S.; Ahmad, F.; Rahman, M.M. An overview of chromium removal techniques from tannery effluent. Appl. Water Sci. 2020, 10, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaiopoulou, E.; Gikas, P. Regulations for chromium emissions to the aquatic environment in Europe and elsewhere. Chemosphere 2020, 254, 126876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves Miranda, G.; Soares dos Santos, F.; Lourenço Pereira Cardoso, M.; Etterson, M.; Amorim, C.C.; Starling, M.C.V.M. Proposal of novel Predicted No Effect Concentrations (PNEC) for metals in freshwater using Species Sensitivity Distribution for different taxonomic groups. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament and the Council of the European Union DIRECTIVE (EU) 2020/2184 OF THE COUNCIL of 16 December 2020 on the quality of water intended for human consumption (recast). Off. J. Eur. Union 2020, L435, 1–62.

- Presidência do Conselho de Ministros Decreto-Lei n.o 69/2023, de 21 de agosto. Diário da República-I Série, n.o 161. 2023; pp. 10–73.

- European Chemicals Agency. ECHA Proposes Restrictions on Chromium(VI) Substances to Protect Health. Available online: https://echa.europa.eu/-/echa-proposes-restrictions-on-chromium-vi-substances-to-protect-health (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Markiewicz, B.; Komorowicz, I.; Sajnóg, A.; Belter, M.; Barałkiewicz, D. Chromium and its speciation in water samples by HPLC/ICP-MS—Technique establishing metrological traceability: A review since 2000. Talanta 2015, 132, 814–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, J.E.T. On the GF-AAS Determination of Chromium in Water Samples. In Proceedings of the Environment and Water Resource Management/837: Health Informatics/838: Modelling and Simulation/839: Power and Energy Systems; ACTAPRESS: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Melaku, S.; Cornelis, R.; Vanhaecke, F.; Dams, R.; Moens, L. Method Development for the Speciation of Chromium in River and Industrial Wastewater Using GFAAS. Microchim. Acta 2005, 150, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANAWAR, H.M.; SAFIULLAH, S.; YOSHIOKA, T. Environmental Exposure Assessment of Chromium and Other Tannery Pollutants at Hazaribagh Area, Dhaka, Bangladesh, and Health Risk. J. Environ. Chem. 2000, 10, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, E.A.; Luz, C.C.; de Carvalho, D.P.; Dorea, C.C.; de Holanda, I.B.B.; Manzatto, Â.G.; Bastos, W.R. Chromium distribution in an Amazonian river exposed to tannery effluent. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 22019–22026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leghouchi, E.; Laib, E.; Guerbet, M. Evaluation of chromium contamination in water, sediment and vegetation caused by the tannery of Jijel (Algeria): A case study. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2009, 153, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominik, J.; Vignati, D.A.L.; Koukal, B.; Pereira de Abreu, M.H.; Kottelat, R.; Szalinska, E.; Baś, B.; Bobrowski, A. Speciation and environmental fate of chromium in rivers contaminated with tannery effluents. Eng. Life Sci. 2007, 7, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolińska, A.; Stępniewska, Z.; Włosek, R. The influence of old leather tannery district on chromium contamination of soils, water and plants. Nat. Sci. 2013, 05, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gameiro, C. Curtumes de Alcanena na Vanguarda Mundial. Available online: https://www.mediotejo.net/curtumes-de-alcanena-na-vanguarda-dos-curtumes-mundiais/ (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Austra SIRECRO–Sistema de Recuperação de Crómio. Available online: https://austra.pt/sirecro-sistema-recuperacao-cromio/ (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Branco, R.; Chung, A.-P.; Verí-ssimo, A.; Morais, P.V. Impact of chromium-contaminated wastewaters on the microbial community of a river. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2005, 54, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, P.F.G.; Martins, N.M.C.; Fontes, P.; Covas, D. Hydroenergy Harvesting Assessment: The Case Study of Alviela River. Water 2021, 13, 1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, R.B.; Eaton, A.D.; Rice, E.W. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 23rd ed.; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA; American Water Works Association: Denver, CO, USA; Water Environment Federation: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; ISBN 9780875532875. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 11885:2007; International Organization for Standardization Water Quality—Determination of Selected Elements by Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES). ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007.

- Li, Z.Q.; Shi, Y.Z.; Gao, P.Y.; Gu, X.X.; Zhou, T.Z. Determination of trace chromium(VI) in water by graphite furnace atomic absorption spectrophotometry after preconcentration on a soluble membrane filter. Fresenius J. Anal. Chem. 1997, 358, 519–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperling, M.; Xu, S.; Welz, B. Determination of Chromium(III) and Chromium(V1) in Water Using Flow Injection On-Line Preconcentration with Selective Adsorption on Activated Alumina and Flame Atomic Absorption Spectrometric Detection. Anal. Chem 1992, 64, 3101–3108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burbridge, D.J.; Koch, I.; Zhang, J.; Reimer, K.J. Chromium speciation in river sediment pore water contaminated by tannery effluent. Chemosphere 2012, 89, 838–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magdeburg, A.; Stalter, D.; Oehlmann, J. Whole effluent toxicity assessment at a wastewater treatment plant upgraded with a full-scale post-ozonation using aquatic key species. Chemosphere 2012, 88, 1008–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.M.P.T.P.T.; Silva, L.J.G.G.; Laranjeiro, C.S.M.M.; Meisel, L.M.; Lino, C.M.; Pena, A. Human pharmaceuticals in Portuguese rivers: The impact of water scarcity in the environmental risk. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 609, 1182–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Haque, M.N.; Lee, S.; Lee, D.-H.; Rhee, J.-S. Exposure to Environmentally Relevant Concentrations of Polystyrene Microplastics Increases Hexavalent Chromium Toxicity in Aquatic Animals. Toxics 2022, 10, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saputro, S.; Yoshimura, K.; Takehara, K.; Matsuoka, S. Narsito Oxidation of Chromium(III) by Free Chlorine in Tap Water during the Chlorination Process Studied by an Improved Solid-Phase Spectrometry. Anal. Sci. 2011, 27, 649–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquanena Aquanena. Available online: https://aquanena.pt/qualidade-da-agua/ (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Wani, K.I.; Naeem, M.; Aftab, T. Chromium in plant-soil nexus: Speciation, uptake, transport and sustainable remediation techniques. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 315, 120350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Silva, L.J.G.; Casimiro, M.J.G.; Pena, A.; Campos, M.J.; Pereira, A.M.P.T. Assessment of Chromium Contamination in Aquatic Environments near Tannery Industries: A Portuguese Case Study. Toxics 2025, 13, 1068. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121068

Silva LJG, Casimiro MJG, Pena A, Campos MJ, Pereira AMPT. Assessment of Chromium Contamination in Aquatic Environments near Tannery Industries: A Portuguese Case Study. Toxics. 2025; 13(12):1068. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121068

Chicago/Turabian StyleSilva, Liliana J. G., Maria J. G. Casimiro, Angelina Pena, Maria J. Campos, and André M. P. T. Pereira. 2025. "Assessment of Chromium Contamination in Aquatic Environments near Tannery Industries: A Portuguese Case Study" Toxics 13, no. 12: 1068. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121068

APA StyleSilva, L. J. G., Casimiro, M. J. G., Pena, A., Campos, M. J., & Pereira, A. M. P. T. (2025). Assessment of Chromium Contamination in Aquatic Environments near Tannery Industries: A Portuguese Case Study. Toxics, 13(12), 1068. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121068