Distribution, Sources, and Ecological Risk Assessment of Microplastics in the Lower Minjiang River

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Sample Collection

2.2. Separation and Identification of Samples

2.3. Quality Control

2.4. Data Sources and Statistical Analysis

2.4.1. Socioeconomic Data

2.4.2. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Ecological Risk Assessment Methods

3. Results

3.1. Distribution Characteristics of MPs

3.1.1. Abundance and Spatiotemporal Distribution of MPs

3.1.2. Levels of MP Pollution

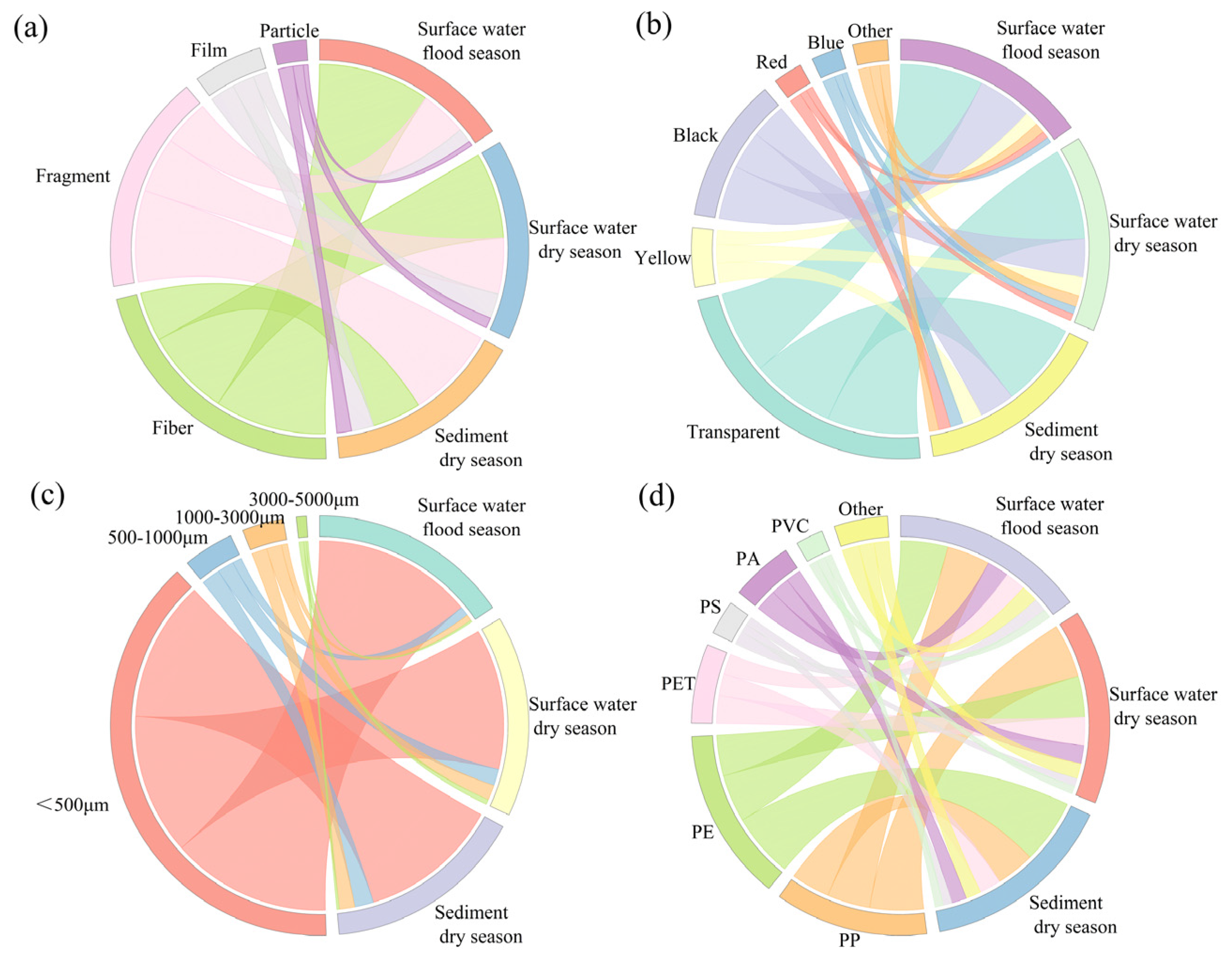

3.1.3. Morphological Characteristics of MPs

3.1.4. Polymer Composition and Distribution of MPs

3.2. Relationship Between MP Abundance and Human Activities and Water Quality Parameters

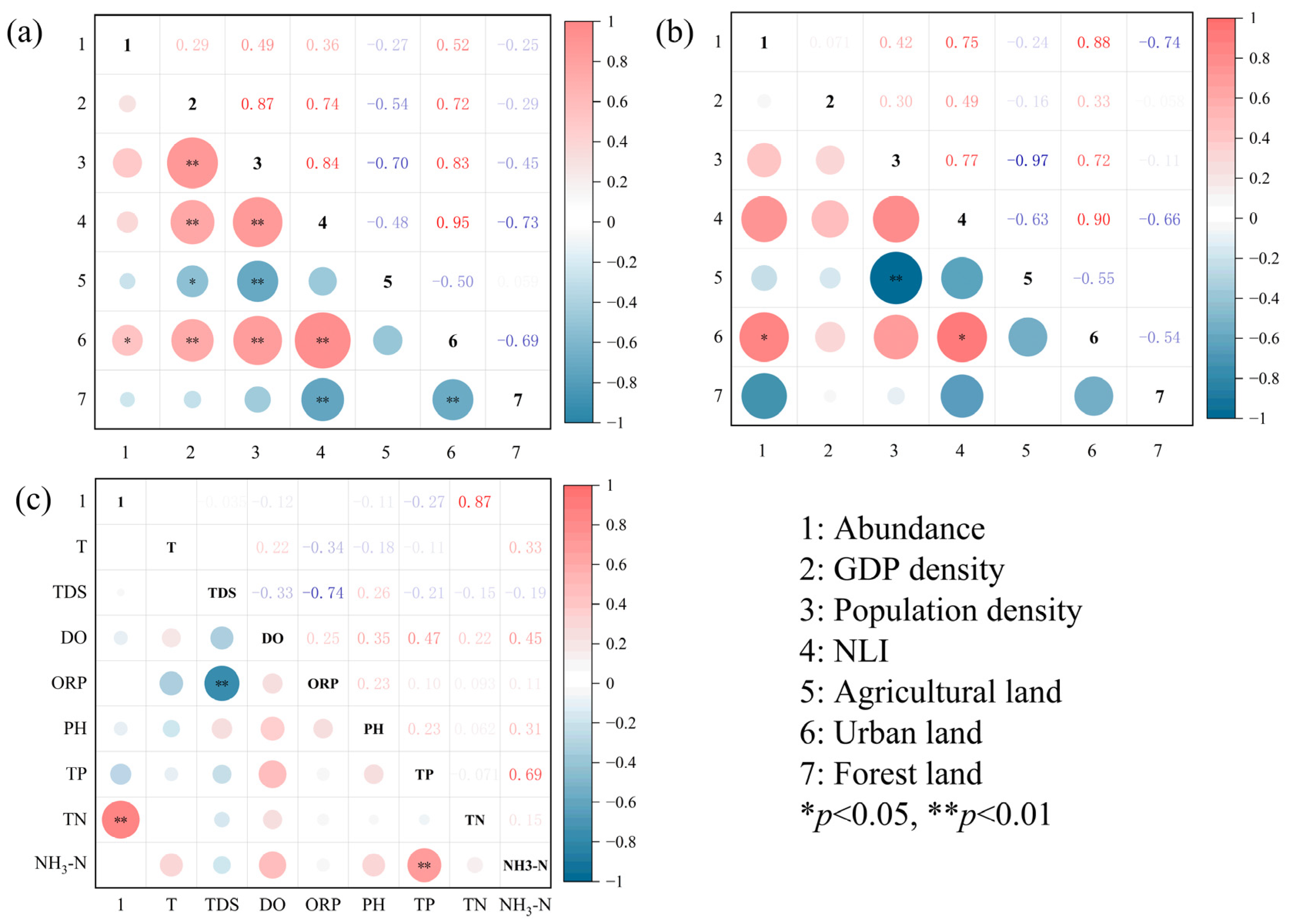

3.2.1. Correlation Between MP Abundance and Socioeconomic Development Indicators

3.2.2. Correlation Between MP Abundance and Water Quality Parameters

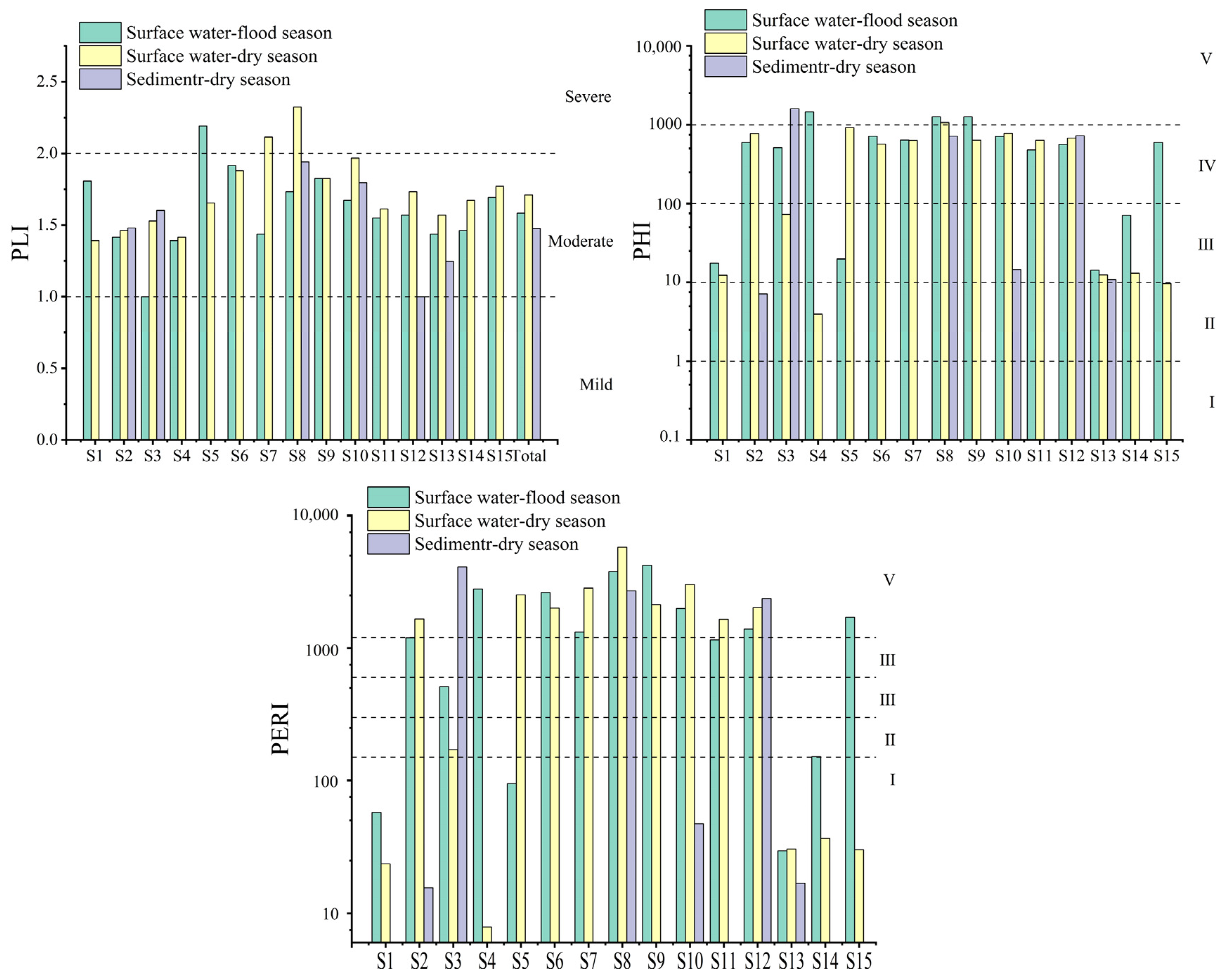

3.3. Ecological Risk Assessment of MPs

4. Discussion

4.1. Analysis of Potential Sources of MPs

4.2. Pollution Risks of MPs and Prevention and Control Measures

4.3. Density Separation Methods and Recycling of MPs

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cox, K.D.; Covernton, G.A.; Davies, H.L.; Dower, J.F.; Juanes, F.; Dudas, S.E. Human Consumption of Microplastics. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 7068–7074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostle, C.; Thompson, R.C.; Broughton, D.; Gregory, L.; Wootton, M.; Johns, D.G. The rise in ocean plastics evidenced from a 60-year time series. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, K.L.; Thompson, R.C. Microplastics in the seas. Science 2014, 345, 144–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrady, A.L. Microplastics in the marine environment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2011, 62, 1596–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy, V.; Blázquez, G.; Calero, M.; Quesada, L.; Martín-Lara, M.A. The potential of microplastics as carriers of metals. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 255, 113363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.Y.; Mamat, Z.; Chen, Y.G. Current research and perspective of microplastics (MPs) in soils (dusts) rivers (lakes), and marine environments in China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 202, 110976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alimi, O.S.; Budarz, J.F.; Hernandez, L.M.; Tufenkji, N. Microplastics and Nanoplastics in Aquatic Environments: Aggregation, Deposition, and Enhanced Contaminant Transport. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 1704–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, H.S.; Xu, S.P.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Q.; Cao, Y.R.; Huang, G.L.; Ruan, Y.F.; Yan, M.; Liu, M.Y.; Zhang, K.; et al. Microplastic occurrence and ecological risk assessment in the eight outlets of the Pearl River Estuary, a new insight into the riverine microplastic input to the northern South China Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 189, 114719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.H.; Zhao, S.; Zhao, L.J.; Duan, X.Y.; Xie, S.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.B.; Peng, Y.W.; Liu, C.G.; Wang, L. Microplastics in Yellow River Delta wetland: Occurrence, characteristics, human influences, and marker. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 258, 113232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico, A.; Redondo-Hasselerharm, P.E.; Vighi, M.; Waichman, A.V.; Nunes, G.S.D.; de Oliveira, R.; Singdahl-Larsen, C.; Hurley, R.; Nizzetto, L.; Scheld, T. Large-scale monitoring and risk assessment of microplastics in the Amazon River. Water Res. 2023, 232, 119707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scircle, A.; Cizdziel, J.V.; Missling, K.; Li, L.; Vianello, A. Single-Pot Method for the Collection and Preparation of Natural Water for Microplastic Analyses: Microplastics in the Mississippi River System during and after Historic Flooding. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2020, 39, 986–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shabaka, S.; Moawad, M.N.; Ibrahim, M.I.A.; El-Sayed, A.A.M.; Ghobashy, M.M.; Hamouda, A.Z.; El-Alfy, M.A.; Darwish, D.H.; Youssef, N.A. Prevalence and risk assessment of microplastics in the Nile Delta estuaries: “The Plastic Nile” revisited. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 852, 158446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Wu, C.X.; Elser, J.J.; Mei, Z.G.; Hao, Y.J. Occurrence and fate of microplastic debris in middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River—From inland to the sea. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 659, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.L.; Tian, M.; Jin, F.; Chen, M.Y.; Liu, Z.G.; He, S.Q.; Li, F.X.; Yang, L.Y.; Fang, C.; Mu, J.L. Coupled effects of urbanization level and dam on microplastics in surface waters in a coastal watershed of Southeast China. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 154, 111089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Xing, R.L.; Sun, M.D.; Ling, W.; Shi, W.Z.; Cui, S.; An, L.H. Microplastics profile in a typical urban river in Beijing. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 743, 140708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, R.R.; Lusher, A.L.; Olsen, M.; Nizzetto, L. Validation of a Method for Extracting Microplastics from Complex, Organic-Rich, Environmental Matrices. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 7409–7417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, G.Y.; Zhu, B.S.; Yang, D.Q.; Su, L.; Shi, H.H.; Li, D.J. Microplastics in sediments of the Changjiang Estuary, China. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 225, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Zhong, Z.; Chen, X.; Sokolova, I.; Ma, L.K.; Yang, Q.K.; Qiu, K.C.; Khan, F.U.; Tu, Z.H.; Guo, B.Y.; et al. Microplastic pollution and ecological risk assessment of Yueqing Bay affected by intensive human activities. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 461, 132603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, D.L.; Wilson, J.G.; Harris, C.R.; Jeffrey, D.W. Problems in the assessment of heavy-metal levels in estuaries and the formation of a pollution index. Helgol. Meeresunters. 1980, 33, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lithner, D.; Larsson, Å.; Dave, G. Environmental and health hazard ranking and assessment of plastic polymers based on chemical composition. Sci. Total Environ. 2011, 409, 3309–3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, G.Y.; Xu, P.; Zhu, B.S.; Bai, M.Y.; Li, D.J. Microplastics in freshwater river sediments in Shanghai, China: A case study of risk assessment in mega-cities. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 234, 448–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, F.Y.; Wang, Y.L.; Wang, D.Q.; Cai, Y.P.; Zhang, J. Seasonal pulse effect of microplastics in the river catchment-From tributary catchment to mainstream. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 342, 118316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Xiong, X.; Hu, H.J.; Wu, C.X.; Bi, Y.H.; Wu, Y.H.; Zhou, B.S.; Lam, P.K.S.; Liu, J.T. Occurrence and Characteristics of Microplastic Pollution in Xiangxi Bay of Three Gorges Reservoir, China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 3794–3801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imhof, H.K.; Schmid, J.; Niessner, R.; Ivleva, N.P.; Laforsch, C. A novel, highly efficient method for the separation and quantification of plastic particles in sediments of aquatic environments. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 2012, 10, 524–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintenig, S.M.; Kooi, M.; Erich, M.W.; Primpke, S.; Redondo-Hasselerharm, P.E.; Dekker, S.C.; Koelmans, A.A.; van Wezel, A.P. A systems approach to understand microplastic occurrence and variability in Dutch riverine surface waters. Water Res. 2020, 176, 115723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devereux, R.; Ayati, B.; Westhead, E.K.; Jayaratne, R.; Newport, D. “The great source” microplastic abundance and characteristics along the river Thames. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 191, 114965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, M.; Singh, P.; Pradhan, V.; Dhanorkar, M. Spatial and seasonal variations in abundance, distribution characteristics, and sources of microplastics in surface water of Mula river in Pune, India. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 373, 126091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Islam, Z.; Hasan, M.R. Pervasiveness and characteristics of microplastics in surface water and sediment of the Buriganga River, Bangladesh. Chemosphere 2022, 307, 135945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M.; Qadir, A.; Mumtaz, M.; Ahmad, S.R. An unintended challenge of microplastic pollution in the urban surface water system of Lahore, Pakistan. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 16718–16730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eo, S.; Hong, S.H.; Song, Y.K.; Han, G.M.; Shim, W.J. Spatiotemporal distribution and annual load of microplastics in the Nakdong River, South Korea. Water Res. 2019, 160, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermaire, J.C.; Pomeroy, C.; Herczegh, S.M.; Haggart, O.; Murphy, M. Microplastic abundance and distribution in the open water and sediment of the Ottawa River, Canada, and its tributaries. FACETS 2017, 2, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, F.C.; Sembiring, E.; Muntalif, B.S.; Suendo, V. Microplastic distribution in surface water and sediment river around slum and industrial area (case study: Ciwalengke River, Majalaya district, Indonesia). Chemosphere 2019, 224, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Zuo, L.Z.; Peng, J.P.; Cai, L.Q.; Fok, L.; Yan, Y.; Li, H.X.; Xu, X.R. Occurrence and distribution of microplastics in an urban river: A case study in the Pearl River along Guangzhou City, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 644, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, L.; Mao, R.F.; Guo, X.T.; Yang, X.M.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, C. Microplastics in surface waters and sediments of the Wei River, in the northwest of China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 667, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.F.; Lu, Q.B.; Yang, J.; Xing, Y.; Ling, W.; Liu, K.; Yang, Q.Z.; Ma, H.J.; Pei, Z.X.; Wu, T.Q.; et al. The fate of microplastic pollution in the Changjiang River estuary: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 425, 138970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.D.; Cai, C.Y.; He, Y.; Chen, L.Y.; Xiong, X.; Huang, H.J.; Tao, S.; Liu, W.X. Occurrence and characteristics of microplastics in the Haihe River: An investigation of a seagoing river flowing through a megacity in northern China. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 262, 114261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, L.; Xue, Y.G.; Li, L.Y.; Yang, D.Q.; Kolandhasamy, P.; Li, D.J.; Shi, H.H. Microplastics in Taihu Lake, China. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 216, 711–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, W.K.; Liu, X.N.; Wang, W.F.; Di, M.X.; Wang, J. Microplastic abundance, distribution and composition in water, sediments, and wild fish from Poyang Lake, China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 170, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, M.X.; Wang, J. Microplastics in surface waters and sediments of the Three Gorges Reservoir, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 616, 1620–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.R.; Shang, Y.X.; Zheng, Y.X.; Jia, Y.Q.; Wang, F.F. Temporal and spatial variation of microplastics in Baotou section of Yellow River, China. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 338, 117803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, A.A.; Svendsen, C.; Williams, R.J.; Spurgeon, D.J.; Lahive, E. Large microplastic particles in sediments of tributaries of the River Thames, UK—Abundance, sources and methods for effective quantification. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 114, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, S.; Horton, A.A.; Rose, N.L.; Hall, C. A temporal sediment record of microplastics in an urban lake, London, UK. J. Paleolimnol. 2019, 61, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, H.A.; Brandsma, S.H.; Van Velzen, M.J.M.; Vethaak, A.D. Microplastics en route: Field measurements in the Dutch river delta and Amsterdam canals, wastewater treatment plants, North Sea sediments and biota. Environ. Int. 2017, 101, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, S.; Worch, E.; Knepper, T.P. Occurrence and Spatial Distribution of Microplastics in River Shore Sediments of the Rhine-Main Area in Germany. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 6070–6076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon-Sánchez, L.; Grelaud, M.; Garcia-Orellana, J.; Ziveri, P. River Deltas as hotspots of microplastic accumulation: The case study of the Ebro River (NW Mediterranean). Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 687, 1186–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, D.J.; Das Sarkar, S.; Das, B.K.; Manna, R.K.; Behera, B.K.; Samanta, S. Spatial distribution of meso and microplastics in the sediments of river Ganga at eastern India. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 694, 133712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corcoran, P.L.; Norris, T.; Ceccanese, T.; Walzak, M.J.; Helm, P.A.; Marvin, C.H. Hidden plastics of Lake Ontario, Canada and their potential preservation in the sediment record. Environ. Pollut. 2015, 204, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, E.K.; Paglialonga, L.; Czech, E.; Tamminga, M. Microplastic pollution in lakes and lake shoreline sediments—A case study on Lake Bolsena and Lake Chiusi (central Italy). Environ. Pollut. 2016, 213, 648–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shruti, V.C.; Jonathan, M.P.; Rodriguez-Espinosa, P.F.; Rodríguez-González, F. Microplastics in freshwater sediments of Atoyac River basin, Puebla City, Mexico. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 654, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.B.; Yin, L.S.; Li, Z.W.; Wen, X.F.; Luo, X.; Hu, S.P.; Yang, H.Y.; Long, Y.N.; Deng, B.; Huang, L.Z.; et al. Microplastic pollution in the rivers of the Tibet Plateau. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 249, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.F.; Du, C.Y.; Xu, P.; Zeng, G.M.; Huang, D.L.; Yin, L.S.; Yin, Q.D.; Hu, L.; Wan, J.; Zhang, J.F.; et al. Microplastic pollution in surface sediments of urban water areas in Changsha, China: Abundance, composition, surface textures. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 136, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Zhang, K.; Chen, X.C.; Shi, H.H.; Luo, Z.; Wu, C.X. Sources and distribution of microplastics in China’s largest inland lake—Qinghai Lake. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 235, 899–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdogan, Z.; Guven, B. Modeling the settling and resuspension of microplastics in rivers: Effect of particle properties and flow conditions. Water Res. 2024, 264, 122181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, S.Q.; Wu, L.B.; Yang, Y.J.; Yu, X.X.; Liu, Q.X.; Liu, X.L.; Li, Y.Y.; Wang, X.H. Vertical distribution and river-sea transport of microplastics with tidal fluctuation in a subtropical estuary, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 822, 153603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Sun, P.P.; Ma, S.J.; Jin, W.; Zhao, Y.P. The interfacial behaviors of different arsenic species on polyethylene mulching film microplastics: Roles of the plastic additives. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 442, 130037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, A.; Holmes, L.; Thompson, R.C.; Fisher, A.S. Metals and marine microplastics: Adsorption from the environment versus addition during manufacture, exemplified with lead. Water Res. 2020, 173, 115577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, J.X.; Zou, L.; Duan, T.; Qin, L.; Qi, Z.L.; Sun, J.X. Occurrence and distribution of microplastics in surface water and sediments in China’s inland water systems: A critical review. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 331, 129968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binda, G.; Kalcíková, G.; Allan, I.J.; Hurley, R.; Rodland, E.; Spanu, D.; Nizzetto, L. Microplastic aging processes: Environmental relevance and analytical implications. Trac-Trends Anal. Chem. 2024, 172, 117566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.W.; Zhou, Y.; Sui, Q.; Zhou, Y.B. Mechanism and characterization of microplastic aging process: A review. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2023, 17, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Falco, F.; Gullo, M.P.; Gentile, G.; Di Pace, E.; Cocca, M.; Gelabert, L.; Brouta-Agnésa, M.; Rovira, A.; Escudero, R.; Villalba, R.; et al. Evaluation of microplastic release caused by textile washing processes of synthetic fabrics. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 236, 916–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.E.; Liu, M.G.; Cao, X.W.; Liu, Z. Occurrence of microplastics pollution in the Yangtze River: Distinct characteristics of spatial distribution and basin-wide ecological risk assessment. Water Res. 2023, 229, 119431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.Y.; Wang, J.Q.; Zhang, H.B.; Shi, H.H.; Fei, Y.F.; Huang, S.Y.; Tong, Y.Z.; Wen, D.S.; Luo, Y.M.; Barceló, D. Microplastics in agricultural soils on the coastal plain of Hangzhou Bay, east China: Multiple sources other than plastic mulching film. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 388, 121814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Song, K.F.; Tu, C.; Li, L.Z.; Feng, Y.D.; Li, R.J.; Xu, H.; Luo, Y.M. Distribution and weathering characteristics of microplastics in paddy soils following long-term mulching: A field study in Southwest China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 858, 159774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Guo, P.Y.; Zhang, X.Y.; Su, H.T.; Zhang, Y.X.; Wu, Y.M.; Li, Y.Q. Microplastics and accumulated heavy metals in restored mangrove wetland surface sediments at Jinjiang Estuary (Fujian, China). Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 159, 111482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fred-Ahmadu, O.H.; Bhagwat, G.; Oluyoye, I.; Benson, N.U.; Ayejuyo, O.O.; Palanisami, T. Interaction of chemical contaminants with microplastics: Principles and perspectives. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 706, 135978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenner, L.C.; Rotchell, J.M.; Bennett, R.T.; Cowen, M.; Tentzeris, V.; Sadofsky, L.R. Detection of microplastics in human lung tissue using μFTIR spectroscopy. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 831, 154907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, H.A.; Van Velzen, M.J.M.; Brandsma, S.H.; Vethaak, A.D.; Garcia-Vallejo, J.J.; Lamoree, M.H. Discovery and quantification of plastic particle pollution in human blood. Environ. Int. 2022, 163, 107199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragusa, A.; Svelato, A.; Santacroce, C.; Catalano, P.; Notarstefano, V.; Carnevali, O.; Papa, F.; Rongioletti, M.C.A.; Baiocco, F.; Draghi, S.; et al. Plasticenta: First evidence of microplastics in human placenta. Environ. Int. 2021, 146, 106274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panthi, G.; Bajagain, R.; Chaudhary, D.K.; Kim, P.G.; Kwon, J.H.; Hong, Y.S. The release, degradation, and distribution of PVC microplastic-originated phthalate and non-phthalate plasticizers in sediments. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 470, 134167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, A.A.; Walton, A.; Spurgeon, D.J.; Lahive, E.; Svendsen, C. Microplastics in freshwater and terrestrial environments: Evaluating the current understanding to identify the knowledge gaps and future research priorities. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 586, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatmullina, L.; Isachenko, I. Settling velocity of microplastic particles of regular shapes. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 114, 871–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Points | GDP Density (10,000 Yuan/km2) | Population Density (Capita/km2) | NLI (nw/cm2/sr) | Proportion of Land Use Types (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agricultural Land | Urban Land | Forest Land | ||||

| S1 | 3513 | 107 | 1.55 | 23.37 | 4.88 | 46.01 |

| S2 | 4029 | 990 | 10.53 | 36.74 | 25.98 | 5.99 |

| S3 | 107,124 | 1576 | 16.33 | 33.98 | 37.77 | 17.91 |

| S4 | 17,698 | 2452 | 25.51 | 25.80 | 44.06 | 0.47 |

| S5 | 9080 | 584 | 22.78 | 39.04 | 37.44 | 5.75 |

| S6 | 4146 | 1004 | 14.56 | 51.35 | 29.67 | 1.05 |

| S7 | 200,082 | 8759 | 44.63 | 5.13 | 79.25 | 0.00 |

| S8 | 3583 | 1560 | 12.58 | 32.88 | 43.27 | 15.60 |

| S9 | 19,494 | 2553 | 10.56 | 17.73 | 24.20 | 11.54 |

| S10 | 43,649 | 3068 | 21.66 | 6.73 | 44.54 | 6.56 |

| S11 | 16,306 | 845 | 13.30 | 25.11 | 37.92 | 27.46 |

| S12 | 24,248 | 1854 | 5.33 | 21.43 | 19.88 | 57.55 |

| S13 | 15,059 | 394 | 3.47 | 44.69 | 8.51 | 27.07 |

| S14 | 13,978 | 288 | 3.05 | 34.41 | 7.67 | 52.95 |

| S15 | 6046 | 546 | 4.50 | 36.55 | 15.78 | 39.70 |

| Name | Abbreviations | Hazard Factor | Risk Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polyethylene | PE | 11 | Medium |

| Polypropylene | PP | 1 | Negligible |

| Polyethylene glycol terephthalate | PET | 4 | Low |

| Polyamide | PA | 47 | Medium |

| Polyvinyl chloride | PVC | 10,001 | Very High |

| Polystyrene | PS | 30 | Medium |

| Ethylene vinyl acetate | EVA | 9 | Low |

| Polycarbonate | PC | 610 | High |

| Acrylonitrile butadiene styrene | ABS | 6552 | Very High |

| Polyacrylonitrile | PAN | 11,521 | Very High |

| Polyphenylene sulfide | PPS | 897 | High |

| Research Area | Region | Abundance | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Water | Mississippi River | USA | 14–83 n/L | [11] |

| Nile River | Egypt | 0.5–4.38 n/L | [12] | |

| Amsterdam Canal | The Netherlands | 0.67–11.53 n/L | [25] | |

| Thames River | UK | 0.33–12.27 n/L | [26] | |

| Mula River | India | 1561 ± 167 n/L | [27] | |

| Buriganga River | Bangladesh | 4.33–43.67 n/L | [28] | |

| Ravi River | Pakistan | 0.19–16.15 n/L | [29] | |

| Nakdong River | Republic of Korea | 0.293–4.760 n/L | [30] | |

| Ottawa River | Canada | 0.05–0.24 n/L | [31] | |

| Ciwalengke River | Indonesia | 5.85 ± 3.28 n/L | [32] | |

| Pearl River | China | 0.38 ± 7.92 n/L | [33] | |

| Northwest Wei River | China | 3.67–10.7 n/L | [34] | |

| Yangtze River Estuary | China | 1.71 ± 3.12 n/L | [35] | |

| Haihe River | China | 2.64–18.45 n/L | [36] | |

| Taihu Lake | China | 3.4–25.8 n/L | [37] | |

| Poyang Lake | China | 5–34 n/L | [38] | |

| Three Gorges Reservoir | China | 1.597–12.611 n/L | [39] | |

| Yellow River Baotou Section | China | 432.5–2510.83 n/L | [40] | |

| Minjiang River | China | 21.38 ± 1.44 n/L | This study | |

| Sediment | Nakdong River | Republic of Korea | 1970 ± 62 n/kg | [30] |

| Thames River | UK | 660 n/kg | [41] | |

| London City Lakes | UK | 539 n/kg | [42] | |

| Dutch River | The Netherlands | 68–10500 n/kg | [43] | |

| Main River | Germany | 786–1368 n/kg | [44] | |

| Ebro River | Mediterranean | 2052 ± 746 n/kg | [45] | |

| Ganga River | India | 99.27–409.86 n/kg | [46] | |

| Ontario Lake | Canada | 4635 n/kg | [47] | |

| Ottawa River | Canada | 220 n/kg | [31] | |

| Chiusi Lake | Italy | 234 ± 85 n/kg | [48] | |

| Zahuapan River | Mexico | 1633.34 ± 202.56 n/kg | [49] | |

| Pearl River | China | 80–9597 n/kg | [33] | |

| Northwest Wei River | China | 360–1320 n/kg | [34] | |

| Qinghai–Tibet Plateau’s River | China | 50–195 n/kg | [50] | |

| Changsha City Rivers | China | 270.17 ± 48.23–866.59 ± 37.96 n/kg | [51] | |

| Yangtze River Estuary | China | 20–340 n/kg | [21] | |

| Taihu Lake | China | 11.0–234.6 n/kg | [37] | |

| Qinghai Lake | China | 50–1292 n/kg | [52] | |

| Poyang Lake | China | 54–506 n/kg | [38] | |

| Three Gorges Reservoir | China | 25–300 n/kg | [39] | |

| Yellow River Baotou Section | China | 3766.67–6166.67 n/kg | [40] | |

| Minjiang River | China | 728.17 ± 20.51 n/kg | This study |

| Elements | C | O | F | Al | Si | K | Ca | Ti | Fe | Zn | Hg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At (%) | 54.61 | 40.19 | 0.37 | 0.60 | 2.38 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.40 | 0.30 | 0.95 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bao, L.; Hao, J.; Pan, W. Distribution, Sources, and Ecological Risk Assessment of Microplastics in the Lower Minjiang River. Toxics 2025, 13, 1033. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121033

Bao L, Hao J, Pan W. Distribution, Sources, and Ecological Risk Assessment of Microplastics in the Lower Minjiang River. Toxics. 2025; 13(12):1033. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121033

Chicago/Turabian StyleBao, Liqin, Jiayi Hao, and Wenbin Pan. 2025. "Distribution, Sources, and Ecological Risk Assessment of Microplastics in the Lower Minjiang River" Toxics 13, no. 12: 1033. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121033

APA StyleBao, L., Hao, J., & Pan, W. (2025). Distribution, Sources, and Ecological Risk Assessment of Microplastics in the Lower Minjiang River. Toxics, 13(12), 1033. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121033