Di(2-ethylhexyl) Phthalate Alters Primordial Germ Cell Distribution and the Reproductive Neuroendocrine Regulatory Axis in Zebrafish Embryos

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Zebrafish Husbandry and Breeding

2.2. Zebrafish Embryo Exposure

2.3. Imaging and Analyzing PGCs

2.4. RNA Extraction and RT-qPCR Analysis

2.5. Molecular Docking Simulations

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. DEHP Inhibits Expression of Genes Involved in PGC Migration and Distribution

3.2. DEHP Alters Distribution of PGCs

3.3. DEHP Affects Gene Expression Related to Maintenance and Functionality of PGCs

3.4. DEHP Alters Expression of Genes Comprising the Reproductive Neuroendocrine Regulatory Axis

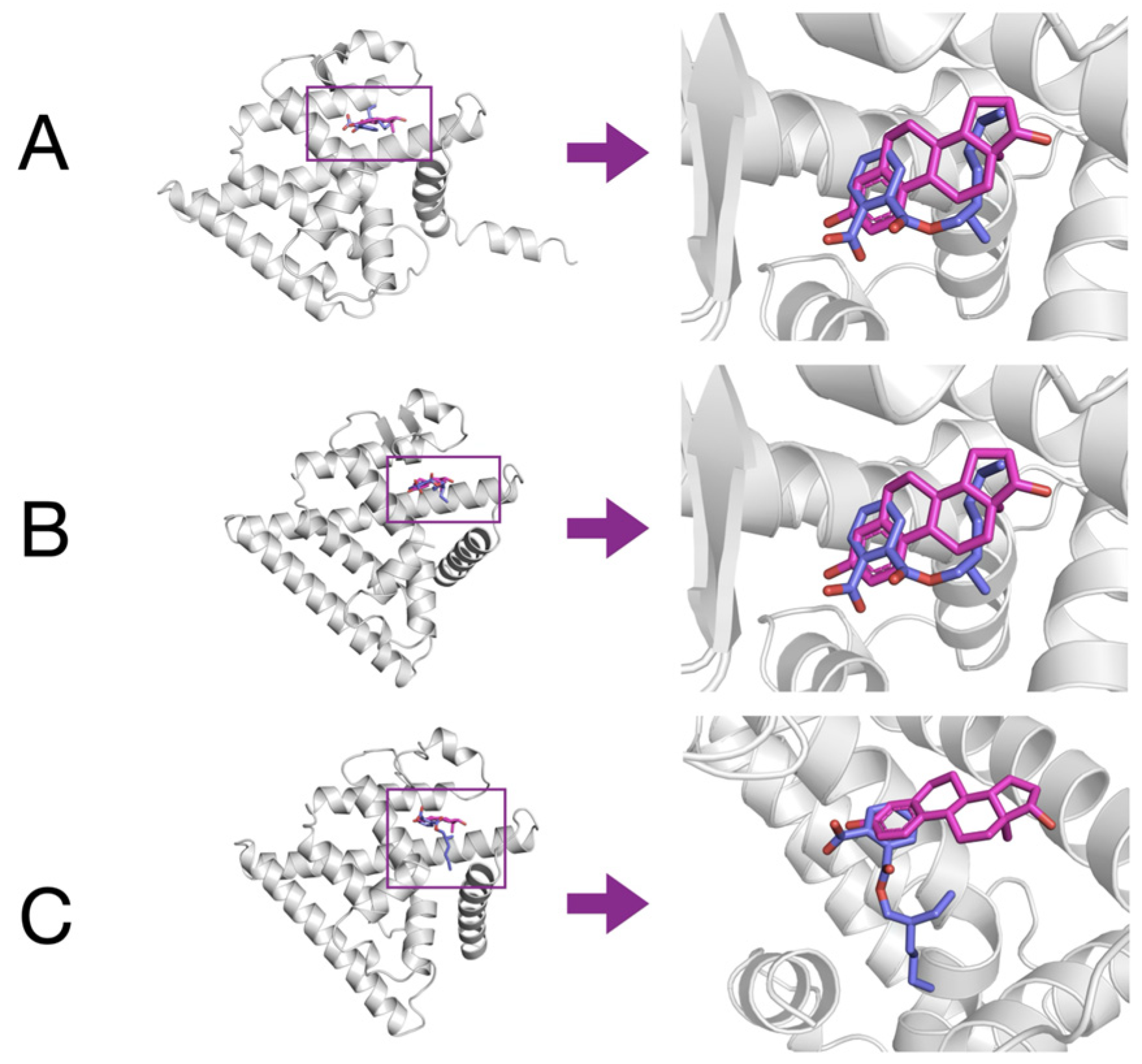

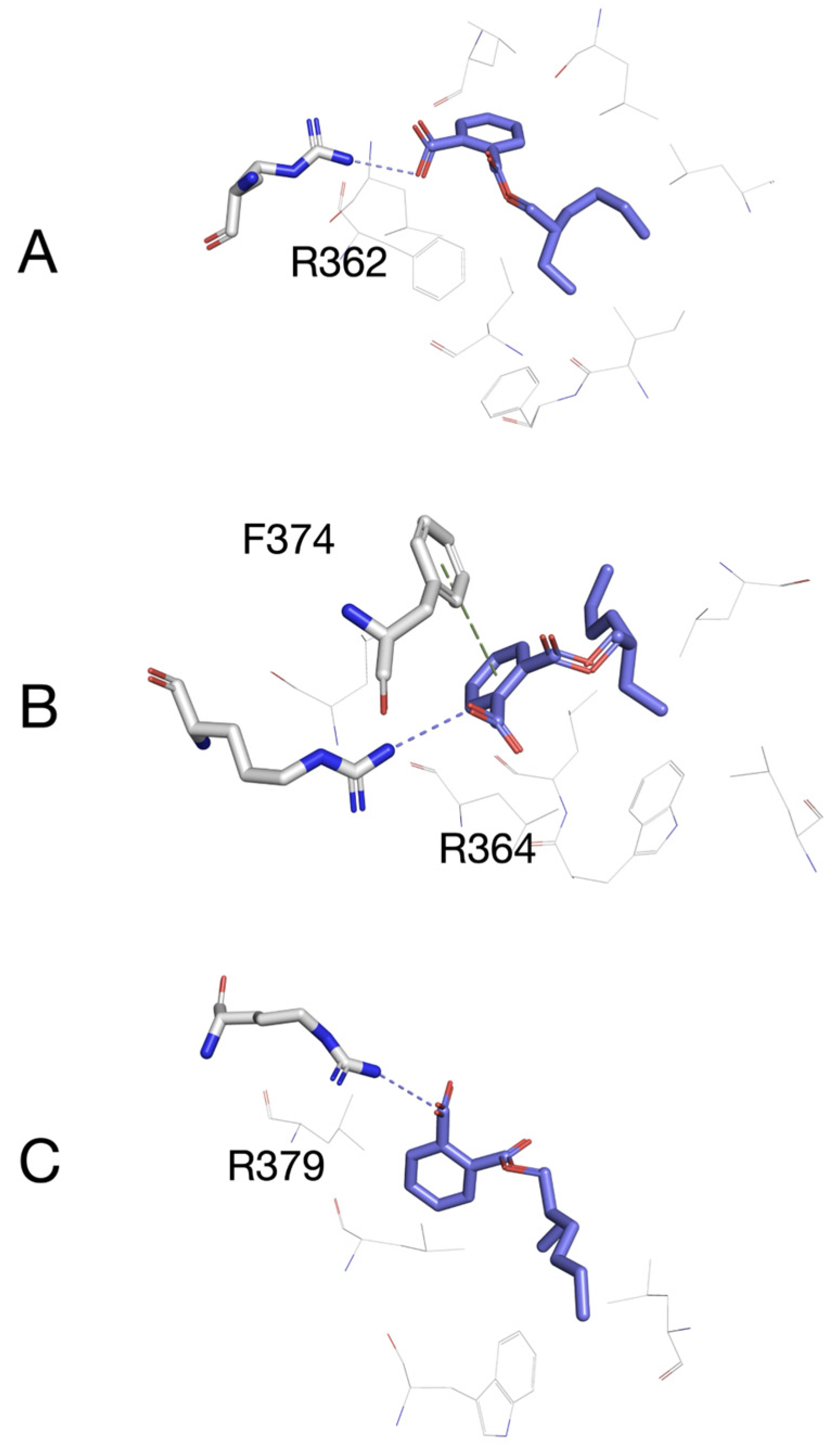

3.5. Molecular Docking of MEHP to Models of Esr1, Esr2a, and Esr2b

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Linghu, D.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, D.; Luo, Y.; Ma, J.; Li, T.; Sun, Z.; Xie, Z.; Sun, J.; Cao, C. Diethylhexyl Phthalate Induces Immune Dysregulation and Is an Environmental Immune Disruptor. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 480, 136244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yi, R.; Tian, Q.; Xu, J.; Yan, X.; Ma, J.; Wang, S.; Yang, G. Exploring the Nephrotoxicity and Molecular Mechanisms of Di-2-Ethylhexyl Phthalate: A Comprehensive Review. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2025, 405, 111310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rusyn, I.; Peters, J.M.; Cunningham, M.L. Effects of DEHP in the Liver: Modes of Action and Species-Specific Differences. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2006, 36, 459–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyman, S.; Acevedo, J.; Giannarelli, C.; Trasande, L. Phthalate Exposure from Plastics and Cardiovascular Disease: Global Estimates of Attributable Mortality and Years Life Lost. eBioMedicine 2025, 117, 105730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.J.; Moon, S.; Oh, B.-C.; Jung, D.; Choi, K.; Park, Y.J. Association Between Diethylhexyl Phthalate Exposure and Thyroid Function: A Meta-Analysis. Thyroid 2019, 29, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, B.J.; Maronpot, R.R.; Heindel, J.J. Di-(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate Suppresses Estradiol and Ovulation in Cycling Rats. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1994, 128, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Li, N.; Zhu, J.; Yu, G.; Guo, K.; Zhou, L.; Zheng, D.; Qu, X.; Huang, J.; Chen, X.; et al. Effects of Di-(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate on the Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Ovarian Axis in Adult Female Rats. Reprod. Toxicol. 2014, 46, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisai, K.; Kumar, V.; Roy, A.; Parida, S.N.; Dhar, S.; Das, B.K.; Behera, B.K.; Pati, M.K. Effects of Di-(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate (DEHP) on Gamete Quality Parameters of Male Koi Carp (Cyprinus carpio). Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2023, 45, 7388–7403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radke, E.G.; Braun, J.M.; Meeker, J.D.; Cooper, G.S. Phthalate Exposure and Male Reproductive Outcomes: A Systematic Review of the Human Epidemiological Evidence. Environ. Int. 2018, 121, 764–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Muhammad, S.; Zhang, Z.; Pavase, T. Combined Exposure of Di (2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate, Dibutyl Phthalate and Acetyl Tributylcitrate: Toxic Effects on the Growth and Reproductive System of Zebrafish (Danio rerio) 1. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Toxicol. 2016, 5, 154–162. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, B.A.; Venkataramanaiah, P.; Srinivasulu Reddy, M. Di-2-Ethylhexyl Phthalate (DEHP) Toxicity: Organ-Specific Impacts and Human-Relevant Findings in Animal Models & Humans—Review. J. Toxicol. Risk Assess. 2025, 11, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jindal, G.; Mangla, A.; Goswami, P.; Javed, M.; Saifi, M.A.; Mazahir, I.; Mudgal, P.; Ahmad, B.; Raisuddin, S. Developmental and Neurobehavioral Toxicity of Di-(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate (DEHP) in Zebrafish Larvae. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2025, 296, 110254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesic, B.; Nedeljkovic, S.F.; Filipovic, J.M.; Nenadov, D.S.; Pogrmic-Majkic, K.; Andric, N. Early-Life Exposure to Di(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate Impairs Reproduction in Adult Female Zebrafish (Danio rerio). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2025, 289, 110090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, X.; Weis, K.; Flaws, J.; Raetzman, L. Prenatal Exposure to the Phthalate DEHP Impacts Reproduction-Related Gene Expression in the Pituitary. Reprod. Toxicol. 2022, 108, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, B.B.H.; Qiu, A.B.; Chen, B.H. Transient Exposure to Environmentally Realistic Concentrations of Di-(2-Ethylhexyl)-Phthalate during Sensitive Windows of Development Impaired Larval Survival and Reproduction Success in Japanese Medaka. Toxicol. Rep. 2020, 7, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.; Joo, H.; Campbell, J.L.; Andersen, M.E.; Clewell, H.J. In Vitro Intestinal and Hepatic Metabolism of Di(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate (DEHP) in Human and Rat. Toxicol. Vitr. 2013, 27, 1451–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanioka, N.; Kinashi, Y.; Tanaka-Kagawa, T.; Isobe, T.; Jinno, H. Glucuronidation of Mono(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate in Humans: Roles of Hepatic and Intestinal UDP-Glucuronosyltransferases. Arch. Toxicol. 2017, 91, 689–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanioka, N.; Isobe, T.; Ohkawara, S.; Ochi, S.; Tanaka-Kagawa, T.; Jinno, H. Hydrolysis of Di(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate in Humans, Monkeys, Dogs, Rats, and Mice: An in Vitro Analysis Using Liver and Intestinal Microsomes. Toxicol. Vitr. 2019, 54, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, H.; Kou, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, C.; Xiang, Z.; Wang, X.; Su, C.; Liu, Y. Toxic Effects of DEHP and MEHP on Gut-Liver Axis in Rats via Intestinal Flora and Metabolomics. iScience 2024, 27, 111135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Mao, G.; Ji, X.; Chen, Y.; Geng, X.; Okeke, E.S.; Ding, Y.; Yang, L.; Wu, X.; Feng, W. Neurodevelopmental Toxicity and Mechanism of Action of Monoethylhexyl Phthalate (MEHP) in the Developing Zebrafish (Danio rerio). Aquat. Toxicol. 2025, 279, 107230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Liu, S.; Li, Y.; Hu, L.; Liao, C.; Jiang, G. Exposure to MEHP during Pregnancy and Lactation Impairs Offspring Growth and Development by Disrupting Thyroid Hormone Homeostasis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 3726–3736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qian, H. Phthalates and Their Impacts on Human Health. Healthcare 2021, 9, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluckman, P.D.; Hanson, M.A.; Buklijas, T. A Conceptual Framework for the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease. J. Dev. Orig. Health Dis. 2010, 1, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laws, M.J.; Neff, A.M.; Brehm, E.; Warner, G.R.; Flaws, J.A. Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals and Reproductive Disorders in Women, Men, and Animal Models. Adv. Pharmacol. 2021, 92, 151–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocar, P.; Fiandanese, N.; Secchi, C.; Berrini, A.; Fischer, B.; Schmidt, J.S.; Schaedlich, K.; Borromeo, V. Exposure to Di(2-Ethyl-Hexyl) Phthalate (DEHP) in Utero and during Lactation Causes Long-Term Pituitary-Gonadal Axis Disruption in Male and Female Mouse Offspring. Endocrinology 2012, 153, 937–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barakat, R.; Lin, P.-C.P.; Rattan, S.; Brehm, E.; Canisso, I.F.; Abosalum, M.E.; Flaws, J.A.; Hess, R.; Ko, C. Prenatal Exposure to DEHP Induces Premature Reproductive Senescence in Male Mice. Toxicol. Sci. 2017, 156, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, T.; Kang, M.; Huang, Q.; Fang, C.; Chen, Y.; Shen, H.; Dong, S. Exposure to DEHP and MEHP from Hatching to Adulthood Causes Reproductive Dysfunction and Endocrine Disruption in Marine Medaka (Oryzias melastigma). Aquat. Toxicol. 2014, 146, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, B.E.; Lehmann, R. Mechanisms Guiding Primordial Germ Cell Migration: Strategies from Different Organisms. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010, 11, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aalto, A.; Olguin-Olguin, A.; Raz, E. Zebrafish Primordial Germ Cell Migration. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 684460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doitsidou, M.; Reichman-Fried, M.; Stebler, J.; Köprunner, M.; Dörries, J.; Meyer, D.; Esguerra, C.V.; Leung, T.; Raz, E. Guidance of Primordial Germ Cell Migration by the Chemokine SDF-1. Cell 2002, 111, 647–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahabaleshwar, H.; Boldajipour, B.; Raz, E. Killing the Messenger. Cell Adhes. Migr. 2008, 2, 69–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köprunner, M.; Thisse, C.; Thisse, B.; Raz, E. A Zebrafish Nanos-Related Gene Is Essential for the Development of Primordial Germ Cells. Genes Dev. 2001, 15, 2877–2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Sun, S.; Guo, M.; Song, H. Use of Antagonists and Morpholinos in Loss-of-Function Analyses: Estrogen Receptor ESR2a Mediates the Effects of 17alpha-Ethinylestradiol on Primordial Germ Cell Distribution in Zebrafish. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2014, 12, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, D.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, Q.; Xiong, F.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.; He, M.; Zhu, Z.; Sun, Y. Abundance of Early Embryonic Primordial Germ Cells Promotes Zebrafish Female Differentiation as Revealed by Lifetime Labeling of Germline. Mar. Biotechnol. 2019, 21, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redl, S.; De Jesus Domingues, A.M.; Caspani, E.; Möckel, S.; Salvenmoser, W.; Mendez-Lago, M.; Ketting, R.F. Extensive Nuclear Gyration and Pervasive Non-Genic Transcription during Primordial Germ Cell Development in Zebrafish. Development 2021, 148, dev193060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, M.; Chen, Y. Zebrafish as an Emerging Model to Study Gonad Development. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 2373–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leu, D.H.; Draper, B.W. The Ziwi Promoter Drives Germline-specific Gene Expression in Zebrafish. Dev. Dyn. 2010, 239, 2714–2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houwing, S.; Berezikov, E.; Ketting, R.F. Zili Is Required for Germ Cell Differentiation and Meiosis in Zebrafish. EMBO J. 2008, 27, 2702–2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertho, S.; Clapp, M.; Banisch, T.U.; Bandemer, J.; Raz, E.; Marlow, F.L. Zebrafish Dazl Regulates Cystogenesis and Germline Stem Cell Specification during the Primordial Germ Cell to Germline Stem Cell Transition. Development 2021, 148, dev187773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aharon, D.; Marlow, F.L. Sexual Determination in Zebrafish. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2021, 79, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vissio, P.G.; Di Yorio, M.P.; Pérez-Sirkin, D.I.; Somoza, G.M.; Tsutsui, K.; Sallemi, J.E. Developmental Aspects of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary Network Related to Reproduction in Teleost Fish. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2021, 63, 100948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L.H.; Cohen, O.; Shulman, M.; Aiznkot, T.; Fontanaud, P.; Revah, O.; Mollard, P.; Golan, M.; Sivan, B.L. The Satiety Hormone Cholecystokinin Gates Reproduction in Fish by Controlling Gonadotropin Secretion. eLife 2024, 13, RP96344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Lin, M.-C.A.; Farajzadeh, M.; Wayne, N.L. Early Development of the Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Neuronal Network in Transgenic Zebrafish. Front. Endocrinol. 2013, 4, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nica, G.; Herzog, W.; Sonntag, C.; Nowak, M.; Schwarz, H.; Zapata, A.G.; Hammerschmidt, M. Eya1 Is Required for Lineage-Specific Differentiation, but Not for Cell Survival in the Zebrafish Adenohypophysis. Dev. Biol. 2006, 292, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Ge, W. Ontogenic Expression Profiles of Gonadotropins (Fshb and Lhb) and Growth Hormone (Gh) During Sexual Differentiation and Puberty Onset in Female Zebrafish1. Biol. Reprod. 2012, 86, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wesselman, H.M.; Wingert, R.A. Estrogen Signaling in Development: Recent Insights from the Zebrafish. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2024, 68, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorelick, D.A.; Watson, W.; Halpern, M.E. Androgen Receptor Gene Expression in the Developing and Adult Zebrafish Brain. Dev. Dyn. 2008, 237, 2987–2995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, W.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, M.; Farajzadeh, M.; Pan, C.; Wayne, N.L. Actions of Bisphenol A and Bisphenol S on the Reproductive Neuroendocrine System During Early Development in Zebrafish. Endocrinology 2016, 157, 636–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochnev, Y.; Hellemann, E.; Cassidy, K.C.; Durrant, J.D. Webina: An Open-Source Library and Web App That Runs AutoDock Vina Entirely in the Web Browser. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 4513–4515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the Speed and Accuracy of Docking with a New Scoring Function, Efficient Optimization and Multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Useini, A.; Engelberger, F.; Künze, G.; Sträter, N. Structural Basis of the Activation of PPARγ by the Plasticizer Metabolites MEHP and MINCH. Environ. Int. 2023, 173, 107822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanwell, M.D.; Curtis, D.E.; Lonie, D.C.; Vandermeersch, T.; Zurek, E.; Hutchison, G.R. Avogadro: An Advanced Semantic Chemical Editor, Visualization, and Analysis Platform. J. Cheminformatics 2012, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hekkelman, M.L.; de Vries, I.; Joosten, R.P.; Perrakis, A. AlphaFill: Enriching AlphaFold Models with Ligands and Cofactors. Nat. Methods 2023, 20, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanenbaum, D.M.; Wang, Y.; Williams, S.P.; Sigler, P.B. Crystallographic Comparison of the Estrogen and Progesterone Receptor’s Ligand Binding Domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 5998–6003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möcklinghoff, S.; Rose, R.; Carraz, M.; Visser, A.; Ottmann, C.; Brunsveld, L. Synthesis and Crystal Structure of a Phosphorylated Estrogen Receptor Ligand Binding Domain. ChemBioChem 2010, 11, 2251–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzozowski, A.M.; Pike, A.C.; Dauter, Z.; Hubbard, R.E.; Bonn, T.; Engström, O.; Ohman, L.; Greene, G.L.; Gustafsson, J.A.; Carlquist, M. Molecular Basis of Agonism and Antagonism in the Oestrogen Receptor. Nature 1997, 389, 753–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schake, P.; Bolz, S.N.; Linnemann, K.; Schroeder, M. PLIP 2025: Introducing Protein–Protein Interactions to the Protein–Ligand Interaction Profiler. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, W463–W465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Küster, E. Cholin- and Carboxylesterase Activities in Developing Zebrafish Embryos (Danio rerio) and Their Potential Use for Insecticide Hazard Assessment. Aquat. Toxicol. 2005, 75, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldajipour, B.; Mahabaleshwar, H.; Kardash, E.; Reichman-Fried, M.; Blaser, H.; Minina, S.; Wilson, D.; Xu, Q.; Raz, E. Control of Chemokine-Guided Cell Migration by Ligand Sequestration. Cell 2008, 132, 463–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussmann, J.; Raz, E. Chemokine-guided Cell Migration and Motility in Zebrafish Development. EMBO J. 2015, 34, 1309–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamba, L.; Cubedo, N.; Ghysen, A.; Lutfalla, G.; Dambly-Chaudière, C. Estrogen Receptor ESR1 Controls Cell Migration by Repressing Chemokine Receptor CXCR4 in the Zebrafish Posterior Lateral Line System. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 6358–6363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombó, M.; Getino-Álvarez, L.; Depincé, A.; Labbé, C.; Herráez, M. Embryonic Exposure to Bisphenol A Impairs Primordial Germ Cell Migration without Jeopardizing Male Breeding Capacity. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willey, J.B.; Krone, P.H. Effects of Endosulfan and Nonylphenol on the Primordial Germ Cell Population in Pre-Larval Zebrafish Embryos. Aquat. Toxicol. 2001, 54, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Xu, S.; Tan, T.; Lee, S.T.; Cheng, S.H.; Lee, F.W.F.; Xu, S.J.L.; Ho, K.C. Toxicity and Estrogenic Endocrine Disrupting Activity of Phthalates and Their Mixtures. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 3156–3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, N.; Junaid, M.; Manzoor, R.; Jia, P.-P.; Pei, D.-S. Prioritizing Phthalate Esters (PAEs) Using Experimental in Vitro/Vivo Toxicity Assays and Computational in Silico Approaches. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 398, 122851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwan, W.S.; Roy, V.A.L.; Yu, K.N. Review on Toxic Effects of Di(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate on Zebrafish Embryos. Toxics 2021, 9, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosado-Berrios, C.A.; Vélez, C.; Zayas, B. Mitochondrial Permeability and Toxicity of Di Ethylhexyl and Mono Ethylhexyl Phthalates on TK6 Human Lymphoblasts Cells. Toxicol. Vitr. 2011, 25, 2010–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, F.; Guo, C.; Wang, L.; Zhang, G.; Wang, J.; Chen, W.; Cui, K.; Tan, Y.; Zhou, Z. Mono-(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate (MEHP)-Induced Telomere Structure and Function Disorder Mediates Cell Cycle Dysregulation and Apoptosis via c-Myc and Its Upstream Transcription Factors in a Mouse Spermatogonia-Derived (GC-1) Cell Line. Toxics 2023, 11, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Sun, S.; Yu, X.; Zhou, J.; Cai, W.; Qian, L. Carboxyl Ester Lipase Is Highly Conserved in Utilizing Maternal Supplied Lipids during Early Development of Zebrafish and Human. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2020, 1865, 158663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatfield, M.J.; Umans, R.A.; Hyatt, J.L.; Edwards, C.C.; Wierdl, M.; Tsurkan, L.; Taylor, M.R.; Potter, P.M. Carboxylesterases: General Detoxifying Enzymes. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2016, 259, 327–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross-Thebing, T.; Yigit, S.; Pfeiffer, J.; Reichman-Fried, M.; Bandemer, J.; Ruckert, C.; Rathmer, C.; Goudarzi, M.; Stehling, M.; Tarbashevich, K.; et al. The Vertebrate Protein Dead End Maintains Primordial Germ Cell Fate by Inhibiting Somatic Differentiation. Dev. Cell 2017, 43, 704–715.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzung, K.-W.; Goto, R.; Saju, J.M.; Sreenivasan, R.; Saito, T.; Arai, K.; Yamaha, E.; Hossain, M.S.; Calvert, M.E.K.; Orbán, L. Early Depletion of Primordial Germ Cells in Zebrafish Promotes Testis Formation. Stem Cell Rep. 2014, 4, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.-T.; Collodi, P. Inducible Sterilization of Zebrafish by Disruption of Primordial Germ Cell Migration. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e68455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weltzien, F.-A.; Hildahl, J.; Hodne, K.; Okubo, K.; Haug, T.M. Embryonic Development of Gonadotrope Cells and Gonadotropic Hormones—Lessons from Model Fish. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2014, 385, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tang, H.; Xie, R.; Li, S.; Liu, X.; Lin, H.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, C.H.K. Genetic Evidence for Multifactorial Control of the Reproductive Axis in Zebrafish. Endocrinology 2017, 158, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Tang, H.; Chen, Y.; Yin, Y.; Ogawa, S.; Liu, M.; Guo, Y.; Qi, X.; Liu, Y.; Parhar, I.S.; et al. Estrogen Directly Stimulates LHb Expression at the Pituitary Level during Puberty in Female Zebrafish. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2018, 461, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okubo, T.; Suzuki, T.; Yokoyama, Y.; Kano, K.; Kano, I. Estimation of Estrogenic and Anti-Estrogenic Activities of Some Phthalate Diesters and Monoesters by MCF-7 Cell Proliferation Assay in Vitro. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2003, 26, 1219–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Lee, J.; Choi, K.; Kim, K.-T. Comparative Analysis of Endocrine Disrupting Effects of Major Phthalates in Employed Two Cell Lines (MVLN and H295R) and Embryonic Zebrafish Assay. Environ. Res. 2019, 172, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, X.; Huang, Y.; Li, J.; Yang, K.; Yang, W.; Shen, G.; Li, X.; Lei, Y.; Pang, S.; Wang, C.; et al. New Insights into the Mechanism of Phthalate-Induced Developmental Effects. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 241, 674–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.-C.; Lau, S.-W.; Ge, W. Spatiotemporal Expression Analysis of Nuclear Estrogen Receptors in the Zebrafish Ovary and Their Regulation in Vitro by Endocrine Hormones and Paracrine Factors. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2017, 246, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagarde, F.; Beausoleil, C.; Belcher, S.M.; Belzunces, L.P.; Emond, C.; Guerbet, M.; Rousselle, C. Non-Monotonic Dose-Response Relationships and Endocrine Disruptors: A Qualitative Method of Assessment. Environ. Health 2015, 14, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene Name | Forward and Reverse Primer Sequence (5′ ⟶ 3′) | Efficiency (%) | Amplicon Length (bp) | Accession Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| elf1a | F CCTGGGATGAAACAGCTGATC R GCTGACTTCCTTGGTGATTTCC | 96.5 | 100 | NM_131263.1 |

| cxcr4b | F CTTACTTACCCGCAGGAGGC R CCAGGCAGCAAAAAGCCAAT | 91 | 83 | NM_131834.1 |

| cxcr7b | F TTCTCCAGGCATCGGAATCT R TCACACTCATCTTGGTCCGT | 101 | 113 | NM_001083832.1 |

| sdf-1a | F ATTCGCGAGCTCAAGTTCCT R ATATCTGTGACGGTGGGCTG | 99 | 214 | NM_178307.2 |

| esr1 | F GTCTGGTCGTGTGAGGGATG R CCCTCCGCGATCTTTACGAA | 101 | 189 | NM_152959.1 |

| esr2a | F ATACCGCCTTGCTCACTGTC R TCGGGATACTCGGACATGGT | 103.5 | 141 | NM_180966.2 |

| esr2b | F TCATGTGAAGGGTGCAAGGC R TCCCTCCTCACACCACACTT | 100.5 | 173 | NM_174862.3 |

| ar | F CACGAGCAGTGGTACCCG R TAGGCAGGTCCTTTGTGGAG | 95 | 180 | NM_001083123.1 |

| cyp19a1 | F CAGGGCATCATATTCAACTCAA R AGGTGGTGCAGATCTCCATAGT | 95 | 112 | NM_131154.3 |

| gnrh3 | F CGGTGGAAAAAGAAGCGTTGG R AACCTTCAGCATCCACCTCATT | 99 | 143 | NM_182887.3 |

| lhb | F ATCGGTGGAAAAAGAGGGCTG R CTGGTGGACGGTGGAAAACG | 104 | 115 | NM_205622.2 |

| fshb | F TGAGCGCAGAATCAGAATG R AGGCTGTGGTGTCGATTGT | 105 | 105 | NM_205624.2 |

| piwil1 | F TACCGCTGCTGGAAAAAGGT R CCTGCAATGACCCCTTCAGT | 94 | 134 | NM_183338.2 |

| piwil2 | F GGTGTCCATGTTCAGGGGTC R TGCTCCAATGATGGTGGGTT | 94 | 130 | NM_001365624.1 |

| nanos1 | F GCAATAAGCAGGAGCCCAAG R GGCTGGTCTTTGGAGAGAGG | 96 | 199 | NM_001305661.1 |

| dazl | F TGCCAAGTATGGCTCAGTGAAA R ATTGCAGGTCCCAGTTTGAGT | 106 | 162 | NM_131524.1 |

| Receptor | Estimated Binding Energy for Estradiol [kCal/mol] | Estimated Binding Energy for MEHP [kCal/mol] |

|---|---|---|

| Esr1 | −7.507 | −5.477 |

| Esr2a | −7.311 | −6.019 |

| Esr2b | −6.314 | −5.45 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tesic, B.; Fa Nedeljkovic, S.; Marinović, Z.; Csenki-Bakos, Z.; Marinović, M.; Petri, E.T.; Pogrmic-Majkic, K.; Stanic, B.; Andric, N. Di(2-ethylhexyl) Phthalate Alters Primordial Germ Cell Distribution and the Reproductive Neuroendocrine Regulatory Axis in Zebrafish Embryos. Toxics 2025, 13, 1032. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121032

Tesic B, Fa Nedeljkovic S, Marinović Z, Csenki-Bakos Z, Marinović M, Petri ET, Pogrmic-Majkic K, Stanic B, Andric N. Di(2-ethylhexyl) Phthalate Alters Primordial Germ Cell Distribution and the Reproductive Neuroendocrine Regulatory Axis in Zebrafish Embryos. Toxics. 2025; 13(12):1032. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121032

Chicago/Turabian StyleTesic, Biljana, Svetlana Fa Nedeljkovic, Zoran Marinović, Zsolt Csenki-Bakos, Maja Marinović, Edward T. Petri, Kristina Pogrmic-Majkic, Bojana Stanic, and Nebojsa Andric. 2025. "Di(2-ethylhexyl) Phthalate Alters Primordial Germ Cell Distribution and the Reproductive Neuroendocrine Regulatory Axis in Zebrafish Embryos" Toxics 13, no. 12: 1032. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121032

APA StyleTesic, B., Fa Nedeljkovic, S., Marinović, Z., Csenki-Bakos, Z., Marinović, M., Petri, E. T., Pogrmic-Majkic, K., Stanic, B., & Andric, N. (2025). Di(2-ethylhexyl) Phthalate Alters Primordial Germ Cell Distribution and the Reproductive Neuroendocrine Regulatory Axis in Zebrafish Embryos. Toxics, 13(12), 1032. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121032