Effectiveness of HEPA/Carbon Filter Air Purifier in Reducing Indoor NO2 and PM2.5 in Homes with Gas Stove Use in Lowell, Massachusetts

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Indoor Environmental Sampling

2.2. Interventions

2.3. Statistical Analysis

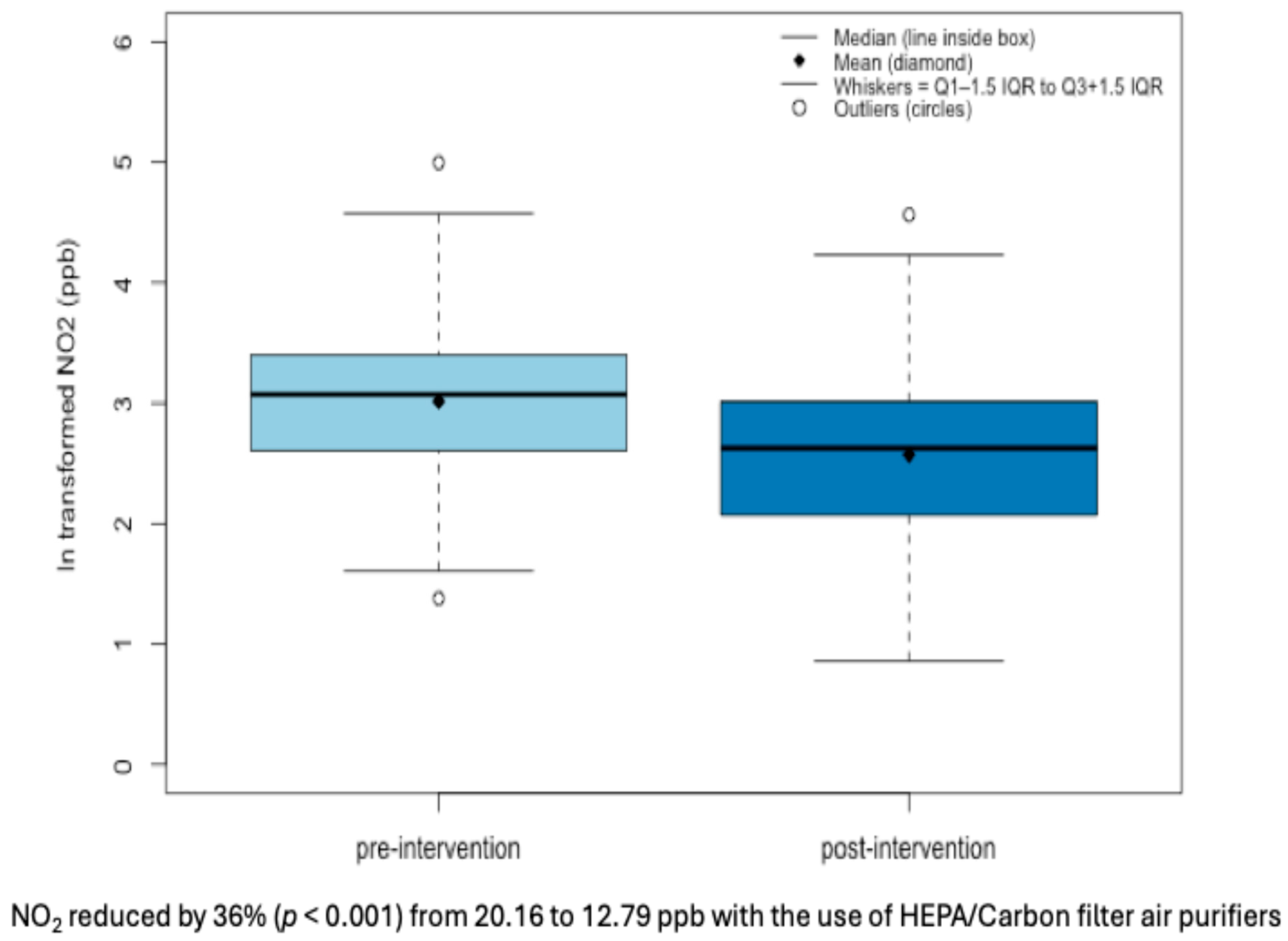

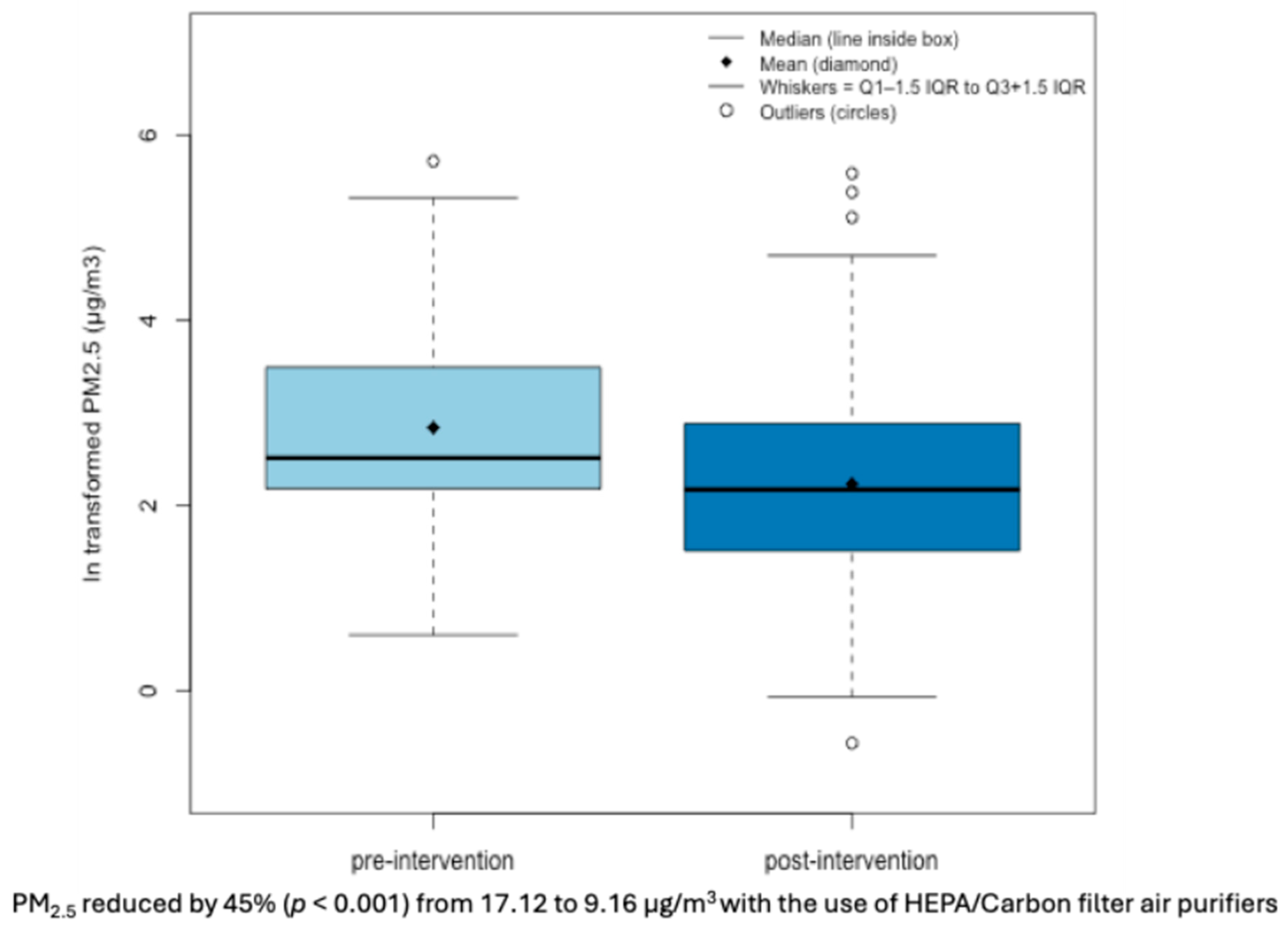

3. Results

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| BIC | Bayesian Information Criterion |

| CHW | Community Health Worker |

| COPD | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| EPA | Environmental Protection Agency |

| GM | Geometric Mean |

| GSD | Geometric Standard Deviation |

| HEPA | High Efficiency Particulate Air |

| LMM | Linear Mixed Model |

| NO2 | Nitrogen Dioxide |

| PM2.5 | Particulate Matter 2.5 microns |

| REDCap | Research Electronic Data Capture |

References

- Buchholz, K. Electric or Gas? What the U.S. Is Cooking On Statista—Environmental Regulations 2023. Available online: https://www.statista.com/chart/29082/most-common-type-of-stove-in-the-us/ (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Balmes, J.R.; Holm, S.M.; McCormack, M.C.; Hansel, N.N.; Gerald, L.B.; Krishnan, J.A. Cooking with Natural Gas: Just the Facts, Please. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2023, 207, 996–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, B.C.; Pass, R.Z.; Delp, W.W.; Lorenzetti, D.M.; Maddalena, R.L. Pollutant concentrations and emission rates from natural gas cooking burners without and with range hood exhaust in nine California homes. Build. Environ. 2017, 122, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebel, E.D.; Finnegan, C.J.; Ouyang, Z.; Jackson, R.B. Methane and NOx Emissions from Natural Gas Stoves, Cooktops, and Ovens in Residential Homes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 2529–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulin, L.M.; Williams, D.L.; Peng, R.; Diette, G.B.; McCormack, M.C.; Breysse, P.; Hansel, N.N. 24-h Nitrogen dioxide concentration is associated with cooking behaviors and an increase in rescue medication use in children with asthma. Environ. Res. 2017, 159, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, W.; Brunekreef, B.; Gehring, U. Meta-analysis of the effects of indoor nitrogen dioxide and gas cooking on asthma and wheeze in children. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2013, 42, 1724–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zota, A.; Adamkiewicz, G.; Levy, J.I.; Spengler, J.D. Ventilation in public housing: Implications for indoor nitrogen dioxide concentrations. Indoor Air 2005, 15, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zusman, M.; Gassett, A.J.; Kirwa, K.; Barr, R.G.; Cooper, C.B.; Han, M.K.; Kanner, R.E.; Koehler, K.; Ortega, V.E.; Paine, R., 3rd; et al. Modeling residential indoor concentrations of PM2.5, NO2, NOx, and secondhand smoke in the Subpopulations and Intermediate Outcome Measures in COPD (SPIROMICS) Air study. Indoor Air 2021, 31, 702–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, R.; Samet, J.M. A review of the epidemiological evidence on health effects of nitrogen dioxide exposure from gas stoves. J. Environ. Med. 1999, 1, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott Downen, R.; Dong, Q.; Chorvinsky, E.; Li, B.; Tran, N.; Jackson, J.H.; Pillai, D.K.; Zaghloul, M.; Li, Z. Personal NO2 sensor demonstrates feasibility of in-home exposure measurements for pediatric asthma research and management. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2022, 32, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dėdelė, A.; Miškinytė, A. Seasonal variation of indoor and outdoor air quality of nitrogen dioxide in homes with gas and electric stoves. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 17784–17792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marbury, M.C.; Harlos, D.P.; Samet, J.M.; Spengler, J.D. Indoor Residential NO2 Concentrations in Albuquerque, New Mexico. J. APCA 1988, 38, 392–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) Table. 2023. Available online: https://www.ccacoalition.org/resources/naaqs-table (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Fabian, P.; Adamkiewicz, G.; Levy, J.I. Simulating indoor concentrations of NO2 and PM2.5 in multifamily housing for use in health-based intervention modeling. Indoor Air 2012, 22, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Cao, S.; Fan, D.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, B.; Zhao, X.; Leaderer, B.P.; Shen, G.; Zhang, Y.; Duan, X. Household concentrations and personal exposure of PM2.5 among urban residents using different cooking fuels. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 548–549, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Jarvis, D.; Potts, J.; Casas, L.; Nowak, D.; Heinrich, J.; Aymerich, J.G.; Urrutia, I.; Martinez-Moratalla, J.; Gullón, J.-A.; et al. Gas cooking indoors and respiratory symptoms in the ECRHS cohort. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2024, 256, 114310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulin, L.M.; Samet, J.M.; Rice, M.B. Gas Stoves and Respiratory Health: Decades of Data, but Not Enough Progress. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2023, 20, 1697–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lead, A. Gas Stove Emissions Are a Public Health Concern: Exposure to Indoor Nitrogen Dioxide Increases Risk of Illness in Children, Older Adults, and People with Underlying Health Conditions. 2022. Available online: https://www.apha.org/getcontentasset/9526a86f-bc00-40c4-ba58-d7950217ab40/7ca0dc9d-611d-46e2-9fd3-26a4c03ddcbb/gas_stoves_public_health_concern_20225.pdf?language=en (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Paulin, L.M.; Diette, G.B.; Scott, M.; McCormack, M.C.; Matsui, E.C.; Curtin-Brosnan, J.; Williams, D.L.; Kidd-Taylor, A.; Shea, M.; Breysse, P.N.; et al. Home interventions are effective at decreasing indoor nitrogen dioxide concentrations. Indoor Air 2014, 24, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauh, V.A.; Landrigan, P.J.; Claudio, L. Housing and Health. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1136, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batterman, S.; Du, L.; Mentz, G.; Mukherjee, B.; Parker, E.; Godwin, C.; Chin, J.Y.; O’Toole, A.; Robins, T.; Rowe, Z.; et al. Particulate matter concentrations in residences: An intervention study evaluating stand-alone filters and air conditioners. Indoor Air 2012, 22, 235–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, X.; Li, F.; Xiang, J.; Fang, L.; Chung, M.K.; Day, D.B.; Mo, J.; Weschler, C.J.; Gong, J.; He, L.; et al. Cardiopulmonary effects of overnight indoor air filtration in healthy non-smoking adults: A double-blind randomized crossover study. Environ. Int. 2018, 114, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Li, Z.; Teng, Y.; Barkjohn, K.K.; Norris, C.L.; Fang, L.; Daniel, G.N.; He, L.; Lin, L.; Wang, Q.; et al. Association Between Bedroom Particulate Matter Filtration and Changes in Airway Pathophysiology in Children With Asthma. JAMA Pediatr. 2020, 174, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, C.; Bernstein, D.I.; Cox, J.; Ryan, P.; Wolfe, C.; Jandarov, R.; Newman, N.; Indugula, R.; Reponen, T. HEPA filtration improves asthma control in children exposed to traffic-related airborne particles. Indoor Air 2020, 30, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myatt, T.A.; Minegishi, T.; Allen, J.G.; Macintosh, D.L. Control of asthma triggers in indoor air with air cleaners: A modeling analysis. Environ. Health 2008, 7, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesper, S.J.; Wymer, L.; Coull, B.A.; Koutrakis, P.; Cunningham, A.; Petty, C.R.; Metwali, N.; Sheehan, W.J.; Gaffin, J.M.; Permaul, P.; et al. HEPA filtration intervention in classrooms may improve some students’ asthma. J. Asthma 2023, 60, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, F.; Takaro, T.K. Childhood asthma and environmental interventions. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007, 115, 971–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, A.N.; Anand, P.; George, A.; Mondal, N. A review of strategies and their effectiveness in reducing indoor airborne transmission and improving indoor air quality. Environ. Res. 2022, 213, 113579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheek, E.; Guercio, V.; Shrubsole, C.; Dimitroulopoulou, S. Portable air purification: Review of impacts on indoor air quality and health. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 766, 142585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansel, N.N.; Breysse, P.N.; McCormack, M.C.; Matsui, E.C.; Curtin-Brosnan, J.; Williams, D.A.L.; Moore, J.L.; Cuhran, J.L.; Diette, G.B. A longitudinal study of indoor nitrogen dioxide levels and respiratory symptoms in inner-city children with asthma. Environ. Health Perspect. 2008, 116, 1428–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthaios, V.N.; Rooney, D.; Harrison, R.M.; Koutrakis, P.; Bloss, W.J. NO2 levels inside vehicle cabins with pollen and activated carbon filters: A real world targeted intervention to estimate NO2 exposure reduction potential. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 860, 160395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Minor, B.L.; Elliott, V.; Fernandez, M.; O’Neal, L.; McLeod, L.; Delacqua, G.; Delacqua, F.; Kirby, J.; et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J. Biomed. Inform. 2019, 95, 103208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.A.; Taylor, R.; Thielke, R.; Payne, J.; Gonzalez, N.; Conde, J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009, 42, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LogTag North America. Available online: https://logtagrecorders.com/product/trix-8/ (accessed on 11 March 2024).

- Kadiri, K.; Turcotte, D.; Gore, R.; Bello, A.; Woskie, S.R. Determinants of Indoor NO2 and PM2.5 Concentration in Senior Housing with Gas Stoves. Toxics 2024, 12, 901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semple, S.; Apsley, A.; Maccalman, L. An inexpensive particle monitor for smoker behaviour modification in homes. Tob. Control 2013, 22, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franken, R.; Maggos, T.; Stamatelopoulou, A.; Loh, M.; Kuijpers, E.; Bartzis, J.; Steinle, S.; Cherrie, J.W.; Pronk, A. Comparison of methods for converting Dylos particle number concentrations to PM2.5 mass concentrations. Indoor Air 2019, 29, 450–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dacunto, P.J.; Klepeis, N.E.; Cheng, K.C.; Acevedo-Bolton, V.; Jiang, R.T.; Repace, J.L.; Ott, W.R.; Hildemann, L.M. Determining PM2.5 calibration curves for a low-cost particle monitor: Common indoor residential aerosols. Environ. Sci. Process Impacts 2015, 17, 1959–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Mercado, I.; Canuz, E.; Smith, K.R. Temperature dataloggers as stove use monitors (SUMs): Field methods and signal analysis. Biomass Bioenergy 2012, 47, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riederer, A.M.; Krenz, J.E.; Tchong-French, M.I.; Torres, E.; Perez, A.; Younglove, L.R.; Jansen, K.L.; Hardie, D.C.; Farquhar, S.A.; Sampson, P.D.; et al. Effectiveness of portable HEPA air cleaners on reducing indoor PM2.5 and NH3 in an agricultural cohort of children with asthma: A randomized intervention trial. Indoor Air 2021, 31, 454–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maestas, M.M.; Brook, R.D.; Ziemba, R.A.; Li, F.; Crane, R.C.; Klaver, Z.M.; Bard, R.L.; Spino, C.A.; Adar, S.D.; Morishita, M. Reduction of personal PM2.5 exposure via indoor air filtration systems in Detroit: An intervention study. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2019, 29, 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martenies, S.E.; Batterman, S.A. Effectiveness of Using Enhanced Filters in Schools and Homes to Reduce Indoor Exposures to PM2.5 from Outdoor Sources and Subsequent Health Benefits for Children with Asthma. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 10767–10776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.Y.; Park, C.J.; Kim, K.Y.; Son, Y.-S.; Kang, C.-M.; Wolfson, J.M.; Jung, I.-H.; Lee, S.-J.; Koutrakis, P. Development of an activated carbon filter to remove NO2 and HONO in indoor air. J. Hazard. Mater. 2015, 289, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Görgülü, A.; Koç, Y.; Yağlı, H.; Koç, A. Adsorption of nitrogen dioxide (NO2) for different gas concentrations, temperatures and relative humidities by using activated carbon filter: An experimental study. Int. J. Adv. Eng. Res. Sci. 2018, 5, 2349–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhuang, T.T.; Wei, F.; Zhou, Y.; Cao, Y.; Wu, Z.Y.; Zhu, J.H.; Liu, C. Adsorption of nitrogen oxides by the moisture-saturated zeolites in gas stream. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 162, 866–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Song, X.; Wu, R.; Fang, J.; Liu, L.; Wang, T.; Liu, S.; Xu, H.; Huang, W. A review on reducing indoor particulate matter concentrations from personal-level air filtration intervention under real-world exposure situations. Indoor Air 2021, 31, 1707–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansel, N.N.; Putcha, N.; Woo, H.; Peng, R.; Diette, G.B.; Fawzy, A.; Wise, R.A.; Romero, K.; Davis, M.F.; Rule, A.M.; et al. Randomized Clinical Trial of Air Cleaners to Improve Indoor Air Quality and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Health: Results of the CLEAN AIR Study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 205, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morishita, M.; Adar, S.D.; D’Souza, J.; Ziemba, R.A.; Bard, R.L.; Spino, C.; Brook, R.D. Effect of Portable Air Filtration Systems on Personal Exposure to Fine Particulate Matter and Blood Pressure Among Residents in a Low-Income Senior Facility: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2018, 178, 1350–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barn, P.; Gombojav, E.; Ochir, C.; Laagan, B.; Beejin, B.; Naidan, G.; Boldbaatar, B.; Galsuren, J.; Byambaa, T.; Janes, C.; et al. The effect of portable HEPA filter air cleaners on indoor PM2.5 concentrations and second hand tobacco smoke exposure among pregnant women in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia: The UGAAR randomized controlled trial. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 615, 1379–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkjohn, K.K.; Norris, C.; Cui, X.; Fang, L.; Zheng, T.; Schauer, J.J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Black, M.; Zhang, J.J.; et al. Real-time measurements of PM2.5 and ozone to assess the effectiveness of residential indoor air filtration in Shanghai homes. Indoor Air 2021, 31, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, D.; Du, Y.; Liu, S.; Brunekreef, B.; Meliefste, K.; Zhao, Q.; Chen, J.; Song, X.; Wang, M.; Wang, J.; et al. Cardiorespiratory responses of air filtration: A randomized crossover intervention trial in seniors living in Beijing: Beijing Indoor Air Purifier StudY, BIAPSY. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 603–604, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.W.; Barn, P. Individual- and Household-Level Interventions to Reduce Air Pollution Exposures and Health Risks: A Review of the Recent Literature. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2020, 7, 424–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.K.; Cheng, K.C.; Tetteh, A.O.; Hildemann, L.M.; Nadeau, K.C. Effectiveness of air purifier on health outcomes and indoor particles in homes of children with allergic diseases in Fresno, California: A pilot study. J. Asthma 2017, 54, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, H.K.; Bayer-Oglesby, L.; Colvile, R.; Götschi, T.; Jantunen, M.J.; Künzli, N.; Kulinskaya, E.; Schweizer, C.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J. Determinants of indoor air concentrations of PM2.5, black smoke and NO2 in six European cities (EXPOLIS study). Atmos. Environ. 2006, 40, 1299–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Qi, M.; Chen, Y.; Shen, H.; Liu, J.; Huang, Y.; Chen, H.; Liu, W.; Wang, X.; Liu, J.; et al. Influences of ambient air PM2.5 concentration and meteorological condition on the indoor PM2.5 concentrations in a residential apartment in Beijing using a new approach. Environ. Pollut. 2015, 205, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sørensen, M.; Loft, S.; Andersen, H.V.; Raaschou-Nielsen, O.; Skovgaard, L.T.; Knudsen, L.E.; Nielsen, I.V.; Hertel, O. Personal exposure to PM2.5, black smoke and NO2 in Copenhagen: Relationship to bedroom and outdoor concentrations covering seasonal variation. J. Expo. Anal. Environ. Epidemiol. 2005, 15, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seguel, J.M.; Merrill, R.; Seguel, D.; Campagna, A.C. Indoor Air Quality. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2017, 11, 284–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.; Song, D.; Park, S.; Choi, Y. Particulate matter generation in daily activities and removal effect by ventilation methods in residential building. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 2021, 14, 1665–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, R.O.; Waugh, D.W. Variability and potential sources of summer PM2.5 in the Northeastern United States. Atmos. Environ. 2015, 117, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, D.A.; Creekmore, A. Emissions and exposure to NOx, CO, CO2 and PM2.5 from a gas stove using reference and low-cost sensors. Atmos. Environ. 2024, 331, 120564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Son, Y.J.; Li, L.; Wood, N.; Senerat, A.M.; Pantelic, J. Healthy home interventions: Distribution of PM2.5 emitted during cooking in residential settings. Build. Environ. 2022, 207, 108448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, B.; Kang, I.; Jagota, K.; Elfessi, Z.; Karpen, N.; Farhoodi, S.; Heidarinejad, M.; Rubinstein, I. Study protocol for a 1-year, randomized, single-blind, parallel group trial of stand-alone indoor air filtration in the homes of US military Veterans with moderate to severe COPD in metropolitan Chicago. Trials 2025, 26, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A.K.; Koul, K.; Babu, B. Study of Modern Air Purification and Sterilization Techniques. Environ. Earth Sci. Res. J. 2022, 9, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, H.; Alun, J.; Fatemeh, B. Ethical Considerations in Interventional Studies: A Systematic Review Ethics and Interventional Study. Acta Medica Iran. 2022, 60, 609–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Timeline | Intervention Period | Environmental Data Collected | Intervention After Data Collection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visit 1 | Pre-intervention | NO2, PM2.5, temperature, humidity, stove usage, and environmental questionnaire | None (control period months 1–4) |

| Visit 2 | Pre-intervention | NO2, PM2.5, temperature, humidity, stove usage, and environmental questionnaire | Provided air purifier units with HEPA/carbon/filters in the kitchen and bedroom |

| Visit 3 | Post-intervention | NO2, PM2.5, temperature, humidity, stove usage, environmental questionnaire, environmental inspection, and air purifier usage | Provide typical multifaceted environmental (HEPA Vacuum and dust mite-proof bed casing) and educational interventions. |

| Visit 4 | Post-intervention | NO2, PM2.5, temperature, humidity, stove usage, environmental questionnaire, environmental inspection, and air purifier usage | None (final assessment) |

| Independent Variables (Fixed Effects) | n | Estimate | SE | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presence of air purifier (ref = No) Yes | 261 | −0.45 | 0.06 | <0.001 * |

| Air purifier use (per 10% increase in use) | 259 | −0.06 | 0.01 | <0.001 * |

| Stove (per 10% increase in use) | 257 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.003 * |

| Season (ref = winter) | 261 | |||

| Fall | −0.24 | 0.11 | 0.030 * | |

| Spring | −0.04 | 0.10 | 0.704 | |

| Summer | −0.39 | 0.10 | <0.001 * | |

| Stove Type (ref Autoignition) | 261 | 0.74 | 0.26 | 0.004 * |

| Average Temperature (°C) | 261 | −0.08 | 0.02 | <0.001 * |

| Average Humidity | 261 | −0.01 | 0.003 | 0.001 * |

| Vent (ref-yes) No | 252 | −0.07 | 0.12 | 0.538 |

| Room type (ref-Wall separates kitchen and living area) | 261 | 0.06 | 40.11 | 0.578 |

| Outside Tobacco Smoke (ref-No) Yes | 244 | −0.02 | 0.09 | 0.806 |

| Dryer (ref-No) Yes | 244 | −0.003 | 0.13 | 0.982 |

| Vacuum with HEPA filter (ref-yes) No | 245 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.127 |

| Trucks (ref-No) Yes | 233 | −0.17 | 0.14 | 0.222 |

| Gas Station (ref-No) Yes | 247 | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.428 |

| Independent Variables (Fixed Effects) | n | Estimate | SE | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presence of air purifier (ref = No) Yes | 257 | −0.60 | 0.07 | <0.001 * |

| Air purifier use (per 10% increase in use) | 256 | −0.07 | 0.01 | <0.001 * |

| Stove (per 10% increase in use) | 253 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.229 |

| Season (ref = winter) | 257 | |||

| Fall | 0.01 | 0.13 | 0.960 | |

| Spring | −0.08 | 0.12 | 0.531 | |

| Summer | −0.02 | 0.12 | 0.901 | |

| Stove Type (ref Autoignition) | 257 | 0.21 | 0.41 | 0.604 |

| Average Temperature (°C) | 257 | −0.08 | 0.02 | 0.001 * |

| Average Humidity | 257 | 0.002 | 0.004 | 0.663 |

| Vent (ref-yes) No | 248 | 0.04 | 0.16 | 0.813 |

| Room type (ref-Wall separates kitchen and living area) | 257 | 0.22 | 0.16 | 0.171 |

| Outside Tobacco Smoke (ref-No) Yes | 241 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.252 |

| Dryer (ref-No) Yes | 241 | −0.28 | 0.19 | 0.193 |

| Vacuum with HEPA filter (ref-yes) No | 242 | 0.36 | 0.10 | <0.001 * |

| Wall-to-wall carpet (ref-No) Yes | 235 | 0.11 | 0.18 | 0.526 |

| Air freshener (ref-never) 6–7 days/week | 245 | 0.26 | 0.12 | 0.035 * |

| Trucks (ref-No) Yes | 230 | −0.04 | 0.17 | 0.823 |

| Gas Station (ref–No) Yes | 244 | 0.39 | 0.21 | 0.066 |

| NO2 Predictors (n = 255) | Estimate | SE | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 3.04 | 0.10 | <0.001 |

| Air purifier use (per 10% increase in use) | −0.05 | 0.01 | <0.001 * |

| Stove (per 10% increase in use) | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.005 * |

| Season | |||

| Fall | −0.27 | 0.10 | 0.008 * |

| Spring | −0.12 | 0.09 | 0.193 |

| Summer | −0.45 | 0.09 | <0.001 * |

| Winter (ref) | |||

| PM2.5 Predictors (n = 252) | Estimate | SE | p-value |

| Intercept | 2.86 | 0.15 | <0.001 |

| Air purifier use (per 10% increase in use) | −0.07 | 0.01 | <0.001 * |

| Stove (per 10% increase in use) | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.576 |

| Season | |||

| Fall | −0.03 | 0.12 | 0.795 |

| Spring | −0.18 | 0.11 | 0.107 |

| Summer | −0.09 | 0.11 | 0.418 |

| Winter (ref) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kadiri, K.; Turcotte, D.; Gore, R.; Bello, A.; Rajabiun, S.; Heavner, K.; Woskie, S.R. Effectiveness of HEPA/Carbon Filter Air Purifier in Reducing Indoor NO2 and PM2.5 in Homes with Gas Stove Use in Lowell, Massachusetts. Toxics 2025, 13, 1030. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121030

Kadiri K, Turcotte D, Gore R, Bello A, Rajabiun S, Heavner K, Woskie SR. Effectiveness of HEPA/Carbon Filter Air Purifier in Reducing Indoor NO2 and PM2.5 in Homes with Gas Stove Use in Lowell, Massachusetts. Toxics. 2025; 13(12):1030. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121030

Chicago/Turabian StyleKadiri, Khafayat, David Turcotte, Rebecca Gore, Anila Bello, Serena Rajabiun, Karyn Heavner, and Susan R. Woskie. 2025. "Effectiveness of HEPA/Carbon Filter Air Purifier in Reducing Indoor NO2 and PM2.5 in Homes with Gas Stove Use in Lowell, Massachusetts" Toxics 13, no. 12: 1030. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121030

APA StyleKadiri, K., Turcotte, D., Gore, R., Bello, A., Rajabiun, S., Heavner, K., & Woskie, S. R. (2025). Effectiveness of HEPA/Carbon Filter Air Purifier in Reducing Indoor NO2 and PM2.5 in Homes with Gas Stove Use in Lowell, Massachusetts. Toxics, 13(12), 1030. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121030