Biomonitoring of Environmental Phenols, Phthalate Metabolites, Triclosan, and Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in Humans with Chromatography and Mass Spectrometry

Highlights

- LC–MS enables the highly sensitive, specific, and multi-class detection of endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) in biomonitoring studies, facilitating the quantification of diverse EDCs and supporting exposome-wide assessments.

- LC–MS is crucial for large-scale exposome research. The growing adoption of automated and online sample preparation workflows enhances throughput and reproducibility in EDC biomonitoring.

Abstract

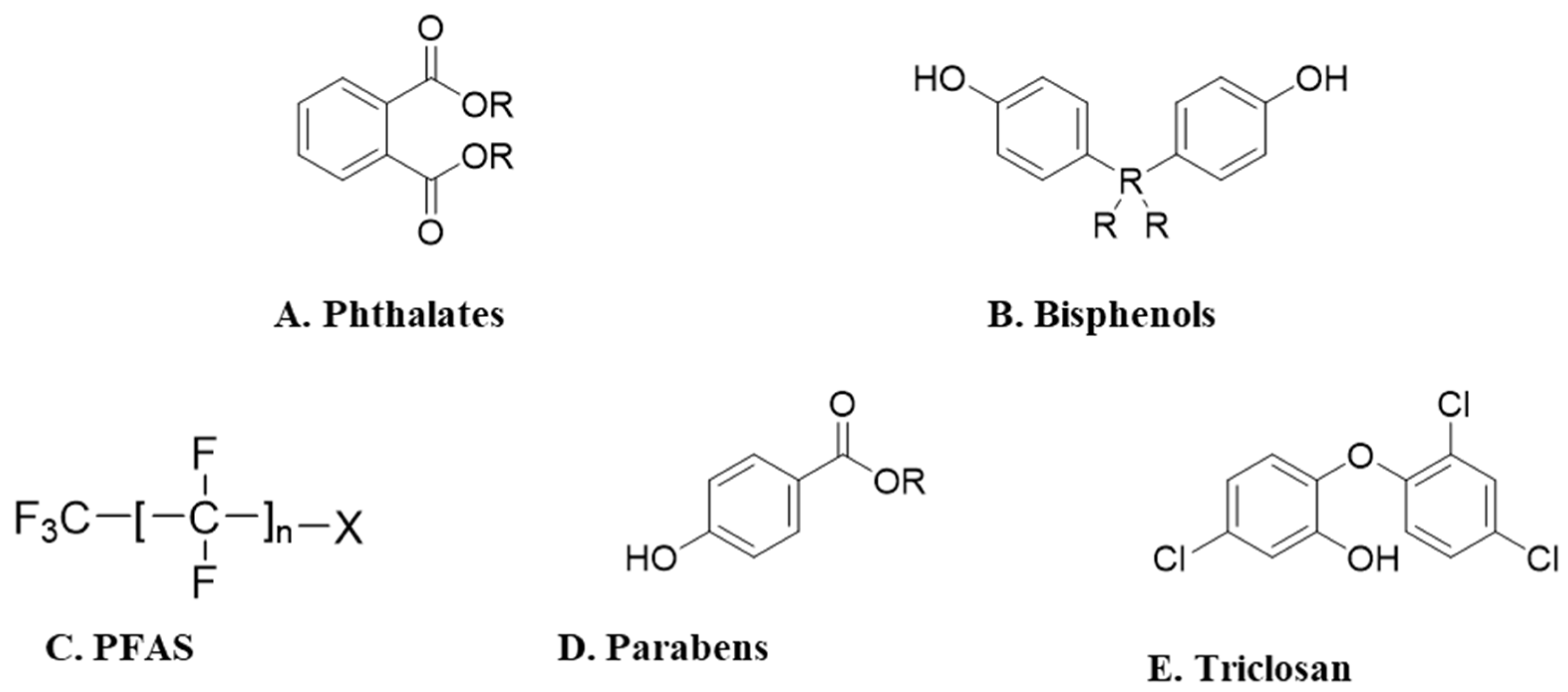

1. Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals

1.1. Bisphenols

1.2. Parabens

1.3. Phthalate Esters

1.4. Triclosan

1.5. Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances

2. Comprehensive Bibliographic Search of Endocrine Disruptors Biomonitoring

- (I)

- Journal articles with titles containing (“pfas”[Title] OR “perfluoroalkyl*”[Title] OR “phthalate*”[Title] OR “paraben*”[Title] OR “BPA”[Title] OR “bisphenol*”[Title] OR “BPS”[Title] OR “BPP”[Title] OR “BPF”[Title] OR “BPAF”[Title] OR “endocrine disruptor*”[Title]) AND (“urin*”[Title] OR “biomonitoring”[Title] OR “blood”[Title] OR “serum”[Title] OR “plasma”[Title]) AND (“method”[Title] OR “detection”[Title] OR “quantitat*”[Title] OR “determination”[Title] OR “*LC”[Title] OR “GC”[Title] OR “chromatograph*”[Title] OR “mass spectrometr*”[Title] OR “analysis*”[Title] OR “measurement”[Title]).

- (II)

- Publications from 1 January 2004, to October 2025.

3. Analysis of Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals in Biological Samples Using Chromatography and Mass Spectrometry Methods Following Human Exposure

4. Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry-Based Techniques

4.1. Sample Preparation

4.2. Instrumental Analysis

5. Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry-Based Techniques

5.1. Sample Preparation

5.2. Instrumental Analysis

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Disclaimer

Abbreviations

| APCI | Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization |

| BPA | Bisphenol-A |

| BPAF | Bisphenol-AF |

| BPF | Bisphenol-F |

| BPP | Bisphenol-P |

| BPS | Bisphenol-S |

| BSTFA | N,O-Bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide) |

| DBS | Dried Blood Spot |

| DLLME | Dispersive Liquid–Liquid Microextraction |

| EDCs | Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals |

| ECNI | Electron Capture Negative Ionization |

| EI | Electron Impact Ionization |

| ESI | Electrospray Ionization |

| GC | Gas Chromatography |

| HF-LPME | Hollow Fiber-Assisted Liquid-phase Microextraction |

| HMW | High Molecular Weight |

| HPLC | High Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| LC | Liquid Chromatography |

| LLE | Liquid–Liquid Extraction |

| LMW | Low Molecular weight |

| MD-GC | Multidimensional Gas Chromatography |

| MEPS | Microextraction using Packed Sorbent |

| MS | Mass Spectrometry |

| MS/MS | Tandem Mass Spectrometry |

| Orbi | Orbitrap |

| PBs | Parabens |

| PEs | Phthalate Esters |

| PFAS | Per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances |

| PFCAs | Perfluoalkyl carboxylic acids |

| PFSAs | Perfluoroalkyl sulphonic acids |

| FASAs | Perfluoroalkane sulphanamids |

| FTS | Fluorotelomer sulphonic acids |

| PTV | Programmed Temperature Vaporizing |

| QuEChERS | Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged and Safe |

| RAM | Restricted Access Material |

| SBSS | Stir Bar Sorptive Extraction |

| SIM | Selected Ion Monitoring |

| SLE | Supported Liquid Extraction |

| SPE | Solid Phase Extraction |

| SPME | Solid Phase MicroExtraction |

| SRM | Selected Reaction Monitoring |

| TCS | Triclosan |

| TD-GC | Thermal Desorption Gas Chromatography |

| UPLC | Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| VADLLME | Vortex-Assisted Dispersive Liquid–Liquid Microextraction |

References

- Kabir, E.R.; Rahman, M.S.; Rahman, I. A Review on Endocrine Disruptors and Their Possible Impacts on Human Health. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2015, 40, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amir, S.; Shah, S.T.A.; Mamoulakis, C.; Docea, A.O.; Kalantzi, O.-I.; Zachariou, A.; Calina, D.; Carvalho, F.; Sofikitis, N.; Makrigiannakis, A.; et al. Endocrine Disruptors Acting on Estrogen and Androgen Pathways Cause Reproductive Disorders through Multiple Mechanisms: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Błędzka, D.; Gromadzińska, J.; Wąsowicz, W. Parabens. From Environmental Studies to Human Health. Environ. Int. 2014, 67, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duty, S.M.; Calafat, A.M.; Silva, M.J.; Ryan, L.; Hauser, R. Phthalate Exposure and Reproductive Hormones in Adult Men. Hum. Reprod. 2005, 20, 604–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeker, J.D. Exposure to Environmental Endocrine Disrupting Compounds and Men’s Health. Maturitas 2010, 66, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calafat, A.M.; Ye, X.; Silva, M.J.; Kuklenyik, Z.; Needham, L.L. Human Exposure Assessment to Environmental Chemicals Using Biomonitoring. Int. J. Androl. 2006, 29, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandborgh-Englund, G.; Adolfsson-Erici, M.; Odham, G.; Ekstrand, J. Pharmacokinetics of Triclosan Following Oral Ingestion in Humans. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A 2006, 69, 1861–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, M.G.; Carabin, I.G.; Burdock, G.A. Safety Assessment of Esters of P-Hydroxybenzoic Acid (Parabens). Food Chem. Toxicol. 2005, 43, 985–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myridakis, A.; Balaska, E.; Gkaitatzi, C.; Kouvarakis, A.; Stephanou, E.G. Determination and Separation of Bisphenol A, Phthalate Metabolites and Structural Isomers of Parabens in Human Urine with Conventional High-Pressure Liquid Chromatography Combined with Electrospray Ionisation Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2015, 407, 2509–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myridakis, A.; Chalkiadaki, G.; Fotou, M.; Kogevinas, M.; Chatzi, L.; Stephanou, E.G. Exposure of Preschool-Age Greek Children (RHEA Cohort) to Bisphenol A, Parabens, Phthalates, and Organophosphates. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 50, 932–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (US). Toxicological Profile for Perfluoroalkyls; Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2021. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37220203/ (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Worley, R.R.; Moore, S.M.; Tierney, B.C.; Ye, X.; Calafat, A.M.; Campbell, S.; Woudneh, M.B.; Fisher, J. Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in Human Serum and Urine Samples from a Residentially Exposed Community. Environ. Int. 2017, 106, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, A.; Chakraborty, P. A Review on Sources and Health Impacts of Bisphenol A. Rev. Environ. Health 2020, 35, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Fang, J.; Ren, L.; Fan, R.; Zhang, J.; Liu, G.; Zhou, L.; Chen, D.; Yu, Y.; Lu, S. Urinary Bisphenol Analogues and Triclosan in Children from South China and Implications for Human Exposure. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 238, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eladak, S.; Grisin, T.; Moison, D.; Guerquin, M.-J.; N’Tumba-Byn, T.; Pozzi-Gaudin, S.; Benachi, A.; Livera, G.; Rouiller-Fabre, V.; Habert, R. A New Chapter in the Bisphenol A Story: Bisphenol S and Bisphenol F are not Safe Alternatives to This Compound. Fertil. Steril. 2015, 103, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Qian, H. Phthalates and Their Impacts on Human Health. Healthcare 2021, 9, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrenk, D.; Bignami, M.; Bodin, L.; Chipman, J.K.; del Mazo, J.; Grasl-Kraupp, B.; Hogstrand, C.; Hoogenboom, L.; Leblanc, J.; Nebbia, C.S.; et al. Risk to Human Health Related to the Presence of Perfluoroalkyl Substances in Food. EFSA J. 2020, 18, e06223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLuca, N.M.; Minucci, J.M.; Mullikin, A.; Slover, R.; Cohen Hubal, E.A. Human Exposure Pathways to Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) from Indoor Media: A Systematic Review. Environ. Int. 2022, 162, 107149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassen, T.H.; Frederiksen, H.; Jensen, T.K.; Petersen, J.H.; Joensen, U.N.; Main, K.M.; Skakkebaek, N.E.; Juul, A.; Jørgensen, N.; Andersson, A.-M. Urinary Bisphenol A Levels in Young Men: Association with Reproductive Hormones and Semen Quality. Environ. Health Perspect. 2014, 122, 478–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-H.; Kim, C.-S.; Park, S.; Han, S.Y.; Pyo, M.-Y.; Yang, M. Gender Differences in the Levels of Bisphenol A Metabolites in Urine. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003, 312, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akash, M.S.H.; Rasheed, S.; Rehman, K.; Imran, M.; Assiri, M.A. Toxicological Evaluation of Bisphenol Analogues: Preventive Measures and Therapeutic Interventions. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 21613–21628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenmai, A.K.; Dybdahl, M.; Pedersen, M.; Alice van Vugt-Lussenburg, B.M.; Wedebye, E.B.; Taxvig, C.; Vinggaard, A.M. Are Structural Analogues to Bisphenol A Safe Alternatives? Toxicol. Sci. 2014, 139, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boberg, J.; Taxvig, C.; Christiansen, S.; Hass, U. Possible Endocrine Disrupting Effects of Parabens and Their Metabolites. Reprod. Toxicol. 2010, 30, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byford, J.R.; Shaw, L.E.; Drew, M.G.B.; Pope, G.S.; Sauer, M.J.; Darbre, P.D. Oestrogenic Activity of Parabens in MCF7 Human Breast Cancer Cells. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2002, 80, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howdeshell, K.L.; Wilson, V.S.; Furr, J.; Lambright, C.R.; Rider, C.V.; Blystone, C.R.; Hotchkiss, A.K.; Gray, L.E. A Mixture of Five Phthalate Esters Inhibits Fetal Testicular Testosterone Production in the Sprague-Dawley Rat in a Cumulative, Dose-Additive Manner. Toxicol. Sci. 2008, 105, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welsh, M.; Saunders, P.T.K.; Fisken, M.; Scott, H.M.; Hutchison, G.R.; Smith, L.B.; Sharpe, R.M. Identification in Rats of a Programming Window for Reproductive Tract Masculinization, Disruption of Which Leads to Hypospadias and Cryptorchidism. J. Clin. Investig. 2008, 118, 1479–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, R. Urinary Phthalate Metabolites and Semen Quality: A Review of a Potential Biomarker of Susceptibility. Int. J. Androl. 2007, 31, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, T.K.; Frederiksen, H.; Kyhl, H.B.; Lassen, T.H.; Swan, S.H.; Bornehag, C.-G.; Skakkebaek, N.E.; Main, K.M.; Lind, D.V.; Husby, S.; et al. Prenatal Exposure to Phthalates and Anogenital Distance in Male Infants from a Low-Exposed Danish Cohort (2010–2012). Environ. Health Perspect. 2016, 124, 1107–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, K.; Silva, M.J.; Needham, L.L.; Calafat, A.M. Determination of 16 Phthalate Metabolites in Urine Using Automated Sample Preparation and On-Line Preconcentration/High-Performance Liquid Chromatography/Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2005, 77, 2985–2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witorsch, R.J. Critical Analysis of Endocrine Disruptive Activity of Triclosan and Its Relevance to Human Exposure through the Use of Personal Care Products. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2014, 44, 535–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayan, A.D. Risk Assessment of Triclosan [Irgasan®] in Human Breast Milk. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2007, 45, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Park, H.; Yang, W.; Lee, J.H. Urinary Concentrations of Bisphenol A and Triclosan and Associations with Demographic Factors in the Korean Population. Environ. Res. 2011, 111, 1280–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philippat, C.; Wolff, M.S.; Calafat, A.M.; Ye, X.; Bausell, R.; Meadows, M.; Stone, J.; Slama, R.; Engel, S.M. Prenatal Exposure to Environmental Phenols: Concentrations in Amniotic Fluid and Variability in Urinary Concentrations during Pregnancy. Environ. Health Perspect. 2013, 121, 1225–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pycke, B.F.G.; Geer, L.A.; Dalloul, M.; Abulafia, O.; Jenck, A.M.; Halden, R.U. Human Fetal Exposure to Triclosan and Triclocarban in an Urban Population from Brooklyn, New York. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 8831–8838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calafat, A.M.; Ye, X.; Wong, L.-Y.; Reidy, J.A.; Needham, L.L. Urinary Concentrations of Triclosan in the U.S. Population: 2003–2004. Environ. Health Perspect. 2008, 116, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovander, T.M.M.; Athanasia, L. Identification of Hydroxylated PCB Metabolites and Other Phenolic Halogenated Pollutants in Human Blood Plasma. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2002, 42, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, W.; Bennett, E.R.; Letcher, R.J. Triclosan in Waste and Surface Waters from the Upper Detroit River by Liquid Chromatography-Electrospray-Tandem Quadrupole Mass Spectrometry. Environ. Int. 2005, 31, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brausch, J.M.; Rand, G.M. A Review of Personal Care Products in the Aquatic Environment: Environmental Concentrations and Toxicity. Chemosphere 2011, 82, 1518–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foran, C.M.; Bennett, E.R.; Benson, W.H. Developmental Evaluation of a Potential Non-Steroidal Estrogen: Triclosan. Mar. Environ. Res. 2000, 50, 153–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishibashi, H.; Matsumura, N.; Hirano, M.; Matsuoka, M.; Shiratsuchi, H.; Ishibashi, Y.; Takao, Y.; Arizono, K. Effects of Triclosan on the Early Life Stages and Reproduction of Medaka Oryzias Latipes and Induction of Hepatic Vitellogenin. Aquat. Toxicol. 2004, 67, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christen, V.; Crettaz, P.; Oberli-Schrämmli, A.; Fent, K. Some Flame Retardants and the Antimicrobials Triclosan and Triclocarban Enhance the Androgenic Activity In Vitro. Chemosphere 2010, 81, 1245–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, E.-M.; An, B.-S.; Choi, K.-C.; Jeung, E.-B. Potential Estrogenic Activity of Triclosan in the Uterus of Immature Rats and Rat Pituitary GH3 Cells. Toxicol. Lett. 2012, 208, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Chakraborty, A.; Kural, M.R.; Roy, P. Alteration of Testicular Steroidogenesis and Histopathology of Reproductive System in Male Rats Treated with Triclosan. Reprod. Toxicol. 2009, 27, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sankoda, K.; Matsuo, H.; Ito, M.; Nomiyama, K.; Arizono, K.; Shinohara, R. Identification of Triclosan Intermediates Produced by Oxidative Degradation Using TiO2 in Pure Water and Their Endocrine Disrupting Activities. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2011, 86, 470–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoker, T.E.; Gibson, E.K.; Zorrilla, L.M. Triclosan Exposure Modulates Estrogen-Dependent Responses in the Female Wistar Rat. Toxicol. Sci. 2010, 117, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorrilla, L.M.; Gibson, E.K.; Jeffay, S.C.; Crofton, K.M.; Setzer, W.R.; Cooper, R.L.; Stoker, T.E. The Effects of Triclosan on Puberty and Thyroid Hormones in Male Wistar Rats. Toxicol. Sci. 2008, 107, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinwiddie, M.; Terry, P.; Chen, J. Recent Evidence Regarding Triclosan and Cancer Risk. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 2209–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lankester, J.; Patel, C.; Cullen, M.R.; Ley, C.; Parsonnet, J. Urinary Triclosan Is Associated with Elevated Body Mass Index in NHANES. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e80057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Reconciling Terminology of the Universe of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances; OECD Series on Risk Management of Chemicals; OECD: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, L.G.; Philippat, C.; Nakayama, S.F.; Slama, R.; Trasande, L. Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals: Implications for Human Health. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020, 8, 703–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjeldsen, L.S.; Bonefeld-Jørgensen, E.C. Perfluorinated Compounds Affect the Function of Sex Hormone Receptors. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 8031–8044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, M.; Ghisari, M.; Bonefeld-Jørgensen, E.C. Effects of Perfluoroalkyl Acids on the Function of the Thyroid Hormone and the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 8045–8056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wielsøe, M.; Kern, P.; Bonefeld-Jørgensen, E.C. Serum Levels of Environmental Pollutants Is a Risk Factor for Breast Cancer in Inuit: A Case Control Study. Environ. Health 2017, 16, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, H.; Harada, K.H.; Kasuga, Y.; Yokoyama, S.; Onuma, H.; Nishimura, H.; Kusama, R.; Yokoyama, K.; Zhu, J.; Harada Sassa, M.; et al. Serum Perfluoroalkyl Substances and Breast Cancer Risk in Japanese Women: A Case-Control Study. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 800, 149316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Liu, H.; Liu, G.; Yu, J.; Liu, N.; Jin, Y.; Bi, Y.; Wang, H. Associations between Polyfluoroalkyl Substances Exposure and Breast Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Toxics 2022, 10, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IARC. Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) and Perfluorooctanesulfonic Acid (PFOS); IARC Monographs on the Identification of Carcinogenic Hazards to Humans; IARC Publications: Lyon, France, 2025; Volume 135, pp. 1–754. [Google Scholar]

- Zahm, S.; Bonde, J.P.; Chiu, W.A.; Hoppin, J.; Kanno, J.; Abdallah, M.; Blystone, C.R.; Calkins, M.M.; Dong, G.-H.; Dorman, D.C.; et al. Carcinogenicity of Perfluorooctanoic Acid and Perfluorooctanesulfonic Acid. Lancet Oncol. 2024, 25, 16–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, A.M.; John, M.W.; Martina, W.; Narayana, R.; Paul, C.; Jane, C.C.; Steven, H.; Ronald, N.S.; Stephen, D.; Anne, H.C. Development of a Method for the Determination of Bisphenol A at Trace Concentrations in Human Blood and Urine and Elucidation of Factors Influencing Method Accuracy and Sensitivity. J. Anal. Toxicol. 2010, 34, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, S.D.; Falk, R.T.; Veenstra, T.D.; Issaq, H.J. Quantitation of Free and Total Bisphenol A in Human Urine Using Liquid Chromatography-tandem Mass Spectrometry. J. Sep. Sci. 2011, 34, 1268–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederiksen, H.; Jørgensen, N.; Andersson, A.-M. Parabens in Urine, Serum and Seminal Plasma from Healthy Danish Men Determined by Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC–MS/MS). J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2010, 21, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

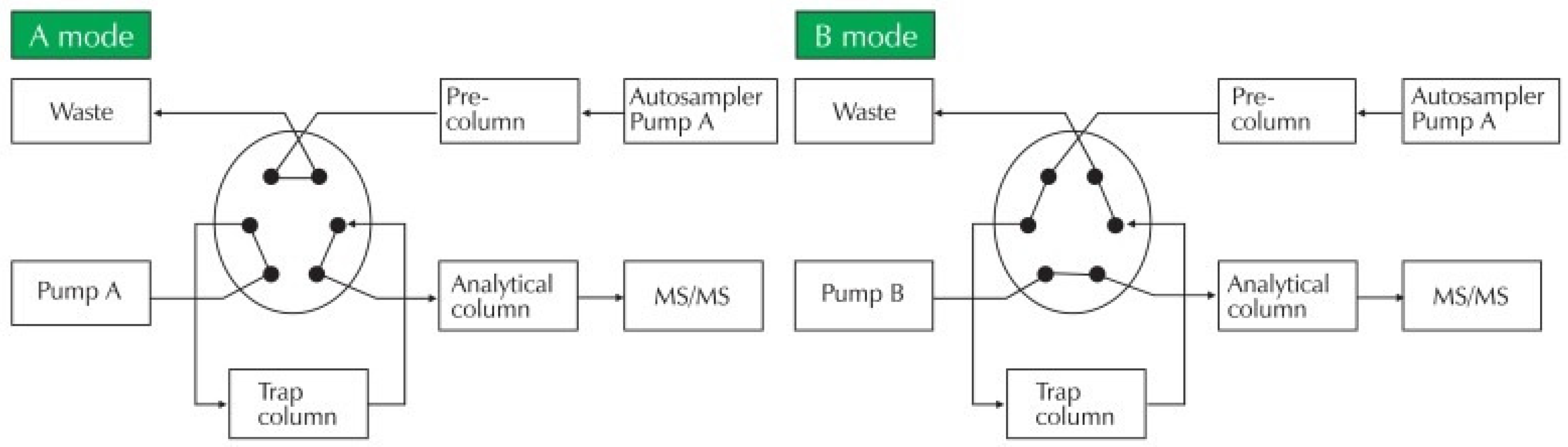

- Jeong, J.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, E.Y.; Kim, P.G.; Kho, Y.L. Determination of Phthalate Metabolites in Human Serum and Urine as Biomarkers for Phthalate Exposure Using Column-Switching LC-MS/MS. Saf. Health Work 2011, 2, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solymos, E.; Guddat, S.; Geyer, H.; Flenker, U.; Thomas, A.; Segura, J.; Ventura, R.; Platen, P.; Schulte-Mattler, M.; Thevis, M.; et al. Rapid Determination of Urinary Di(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate Metabolites Based on Liquid Chromatography/Tandem Mass Spectrometry as a Marker for Blood Transfusion in Sports Drug Testing. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2010, 401, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Tao, L.; Collins, E.M.; Austin, C.; Lu, C. Simultaneous Determination of Multiple Phthalate Metabolites and Bisphenol-A in Human Urine by Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. B 2012, 904, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gries, W.; Ellrich, D.; Küpper, K.; Ladermann, B.; Leng, G. Analytical Method for the Sensitive Determination of Major Di-(2-Propylheptyl)-Phthalate Metabolites in Human Urine. J. Chromatogr. B 2012, 908, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, C.; Kannan, K. Determination of Free and Conjugated Forms of Bisphenol A in Human Urine and Serum by Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 5003–5009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monfort, N.; Ventura, R.; Balcells, G.; Segura, J. Determination of Five Di-(2-Ethylhexyl)Phthalate Metabolites in Urine by UPLC–MS/MS, Markers of Blood Transfusion Misuse in Sports. J. Chromatogr. B 2012, 908, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolucci, C.; Rossi, S.; Menale, C.; del Giudice, E.M.; Perrone, L.; Gallo, P.; Mita, D.G.; Diano, N. A High Selective and Sensitive Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry Method for Quantization of BPA Urinary Levels in Children. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2013, 405, 9139–9148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

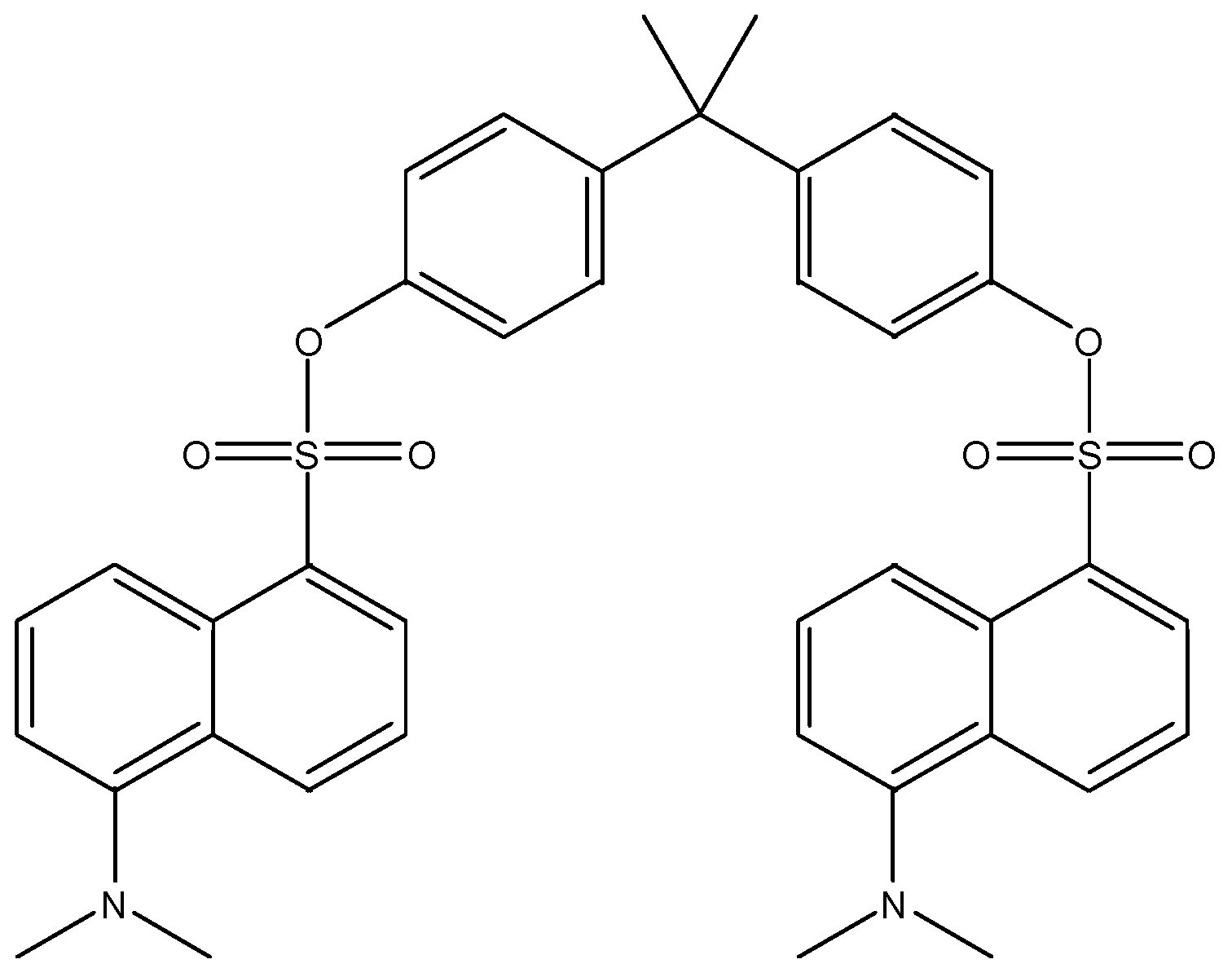

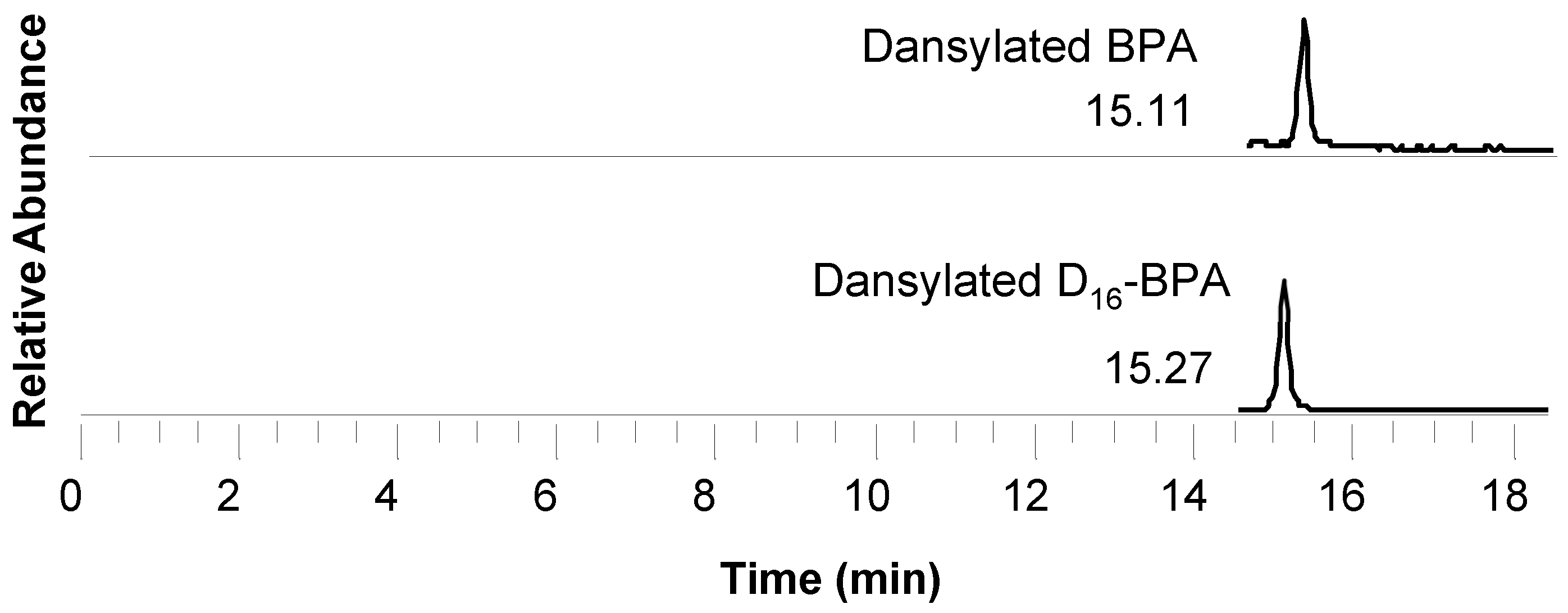

- Wang, H.; Wang, B.; Zhou, Y.; Jiang, Q. Rapid and Sensitive Analysis of Phthalate Metabolites, Bisphenol A, and Endogenous Steroid Hormones in Human Urine by Mixed-Mode Solid-Phase Extraction, Dansylation, and Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography Coupled with Triple Quadrupole Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2013, 405, 4313–4319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asimakopoulos, A.G.; Wang, L.; Thomaidis, N.S.; Kannan, K. A Multi-Class Bioanalytical Methodology for the Determination of Bisphenol A Diglycidyl Ethers, p-Hydroxybenzoic Acid Esters, Benzophenone-Type Ultraviolet Filters, Triclosan, and Triclocarban in Human Urine by Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2014, 1324, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battal, D.; Cok, I.; Unlusayin, I.; Tunctan, B. Development and Validation of an LC-MS/MS Method for Simultaneous Quantitative Analysis of Free and Conjugated Bisphenol A in Human Urine. Biomed. Chromatogr. 2013, 28, 686–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markham, D.; Waechter, J.; Budinsky, R.; Gries, W.; Beyer, D.; Snyder, S.; Dimond, S.; Rajesh, V.N.; Rao, N.; Connolly, P.; et al. Development of a Method for the Determination of Total Bisphenol A at Trace Levels in Human Blood and Urine and Elucidation of Factors Influencing Method Accuracy and Sensitivity. J. Anal. Toxicol. 2014, 38, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Moos, R.K.; Angerer, J.; Wittsiepe, J.; Wilhelm, M.; Brüning, T.; Koch, H.M. Rapid Determination of Nine Parabens and Seven Other Environmental Phenols in Urine Samples of German Children and Adults. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2014, 217, 845–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Kramer, J.P.; Calafat, A.M.; Ye, X. Automated On-Line Column-Switching High Performance Liquid Chromatography Isotope Dilution Tandem Mass Spectrometry Method for the Quantification of Bisphenol A, Bisphenol F, Bisphenol S, and 11 Other Phenols in Urine. J. Chromatogr. B 2014, 944, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Franke, A.A. Improvement of Bisphenol A Quantitation from Urine by LCMS. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2015, 407, 3869–3874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Sabaredzovic, A.; Sakhi, A.K.; Brantsæter, A.L.; Thomsen, C. Determination of 12 Urinary Phthalate Metabolites in Norwegian Pregnant Women by Core–Shell High Performance Liquid Chromatography with on-Line Solid-Phase Extraction, Column Switching and Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. B 2015, 1002, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, B.A.; da Costa, B.R.B.; de Albuquerque, N.C.P.; de Oliveira, A.R.M.; Souza, J.M.O.; Al-Tameemi, M.; Campiglia, A.D.; Barbosa, F., Jr. A Fast Method for Bisphenol A and Six Analogues (S, F, Z, P, AF, AP) Determination in Urine Samples Based on Dispersive Liquid-Liquid Microextraction and Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Talanta 2016, 154, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Ye, Z.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Luo, F.; Sheng, B.; Li, Y.; Lyu, J. Optimization of a NH4PF6-Enhanced, Non-Organic Solvent, Dual Microextraction Method for Determination of Phthalate Metabolites in Urine by High Performance Liquid Chromatography. J. Chromatogr. B 2016, 1014, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heffernan, A.L.; Thompson, K.; Eaglesham, G.; Vijayasarathy, S.; Mueller, J.F.; Sly, P.D.; Gomez, M.J. Rapid, Automated Online SPE-LC-QTRAP-MS/MS Method for the Simultaneous Analysis of 14 Phthalate Metabolites and 5 Bisphenol Analogues in Human Urine. Talanta 2016, 151, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Fang, J.; Liu, G.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, Z.; Liu, H.; Lin, K.; Zhang, H.; Lu, S. Simultaneous Determination of Urinary Parabens, Bisphenol A, Triclosan, and 8-Hydroxy-2′-Deoxyguanosine by Liquid Chromatography Coupled with Electrospray Ionization Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2016, 408, 2621–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Shao, B.; Wu, X.; Sun, X.; Wu, Y. A Study on Bisphenol A, Nonylphenol, and Octylphenol in Human Urine Smples Detected by SPE-UPLC-MS. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 2011, 24, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servaes, K.; Voorspoels, S.; Lievens, J.; Noten, B.; Allaerts, K.; Van De Weghe, H.; Vanermen, G. Direct Analysis of Phthalate Ester Biomarkers in Urine without Preconcentration: Method Validation and Monitoring. J. Chromatogr. A 2013, 1294, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.J.; Brozek, E.M.; Cox, K.J.; Porucznik, C.A.; Wilkins, D.G. Biomonitoring Method for Bisphenol A in Human Urine by Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. B 2014, 953–954, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewalque, L.; Pirard, C.; Dubois, N.; Charlier, C. Simultaneous Determination of Some Phthalate Metabolites, Parabens and Benzophenone-3 in Urine by Ultra High Pressure Liquid Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. B 2014, 949–950, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provencher, G.; Bérubé, R.; Dumas, P.; Bienvenu, J.-F.; Gaudreau, É.; Bélanger, P.; Ayotte, P. Determination of Bisphenol A, Triclosan and Their Metabolites in Human Urine Using Isotope-Dilution Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2014, 1348, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vela-Soria, F.; Ballesteros, O.; Zafra-Gómez, A.; Ballesteros, L.; Navalón, A. UHPLC–MS/MS Method for the Determination of Bisphenol A and Its Chlorinated Derivatives, Bisphenol S, Parabens, and Benzophenones in Human Urine Samples. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2014, 406, 3773–3785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venisse, N.; Grignon, C.; Brunet, B.; Thévenot, S.; Bacle, A.; Migeot, V.; Dupuis, A. Reliable Quantification of Bisphenol A and Its Chlorinated Derivatives in Human Urine Using UPLC–MS/MS Method. Talanta 2014, 125, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buscher, B.; van de Lagemaat, D.; Gries, W.; Beyer, D.; Markham, D.A.; Budinsky, R.A.; Dimond, S.S.; Nath, R.V.; Snyder, S.A.; Hentges, S.G. Quantitative Analysis of Unconjugated and Total Bisphenol A in Human Urine Using Solid-Phase Extraction and UPLC–MS/MS: Method Implementation, Method Qualification and Troubleshooting. J. Chromatogr. B 2015, 1005, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cristina Jardim, V.; de Paula Melo, L.; Soares Domingues, D.; Costa Queiroz, M.E. Determination of Parabens in Urine Samples by Microextraction Using Packed Sorbent and Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography Coupled to Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. B 2015, 974, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, L.; Calvarro, S.; Fernández, M.A.; Quintanilla-López, J.E.; González, M.J.; Gómara, B. Feasibility of Ultra-High Performance Liquid and Gas Chromatography Coupled to Mass Spectrometry for Accurate Determination of Primary and Secondary Phthalate Metabolites in Urine Samples. Anal. Chim. Acta 2015, 853, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- ter Halle, A.; Claparols, C.; Garrigues, J.C.; Franceschi-Messant, S.; Perez, E. Development of an Extraction Method Based on New Porous Organogel Materials Coupled with Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry for the Rapid Quantification of Bisphenol A in Urine. J. Chromatogr. A 2015, 1414, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grignon, C.; Venisse, N.; Rouillon, S.; Brunet, B.; Bacle, A.; Thevenot, S.; Migeot, V.; Dupuis, A. Ultrasensitive Determination of Bisphenol A and Its Chlorinated Derivatives in Urine Using a High-Throughput UPLC-MS/MS Method. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2016, 408, 2255–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauck, Z.Z.; Huang, K.; Li, G.; van Breemen, R.B. Determination of Bisphenol A-glucuronide in Human Urine Using Ultrahigh—Pressure Liquid Chromatography/Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2016, 30, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlittenbauer, L.; Seiwert, B.; Reemtsma, T. Ultrasound-Assisted Hydrolysis of Conjugated Parabens in Human Urine and Their Determination by UPLC–MS/MS and UPLC–HRMS. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2016, 408, 1573–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.-T.; Chen, H.-C.; Ding, W.-H. Accurate Analysis of Parabens in Human Urine Using Isotope-Dilution Ultrahigh-Performance Liquid Chromatography-High Resolution Mass Spectrometry. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2018, 150, 469–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrasco-Correa, E.J.; Vela-Soria, F.; Ballesteros, O.; Ramis-Ramos, G.; Herrero-Martínez, J.M. Sensitive Determination of Parabens in Human Urine and Serum Using Methacrylate Monoliths and Reversed-Phase Capillary Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2015, 1379, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battal, D.; Sukuroglu, A.A.; Kocadal, K.; Cok, I.; Unlusayin, I. Establishment of Rapid, Sensitive, and Quantitative Liquid Chromatography-Electrospray Ionization-Tandem Mass Spectrometry Method Coupled with Liquid–Liquid Extraction for Measurement of Urinary Bisphenol A, 4-t-Octylphenol, and 4-Nonylphenol. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2021, 35, e9084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bocato, M.Z.; Cesila, C.A.; Lataro, B.F.; de Oliveira, A.R.M.; Campíglia, A.D.; Barbosa, F., Jr. A Fast-Multiclass Method for the Determination of 21 Endocrine Disruptors in Human Urine by Using Vortex-Assisted Dispersive Liquid-Liquid Microextraction (VADLLME) and LC-MS/MS. Environ. Res. 2020, 189, 109883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-C.; Chang, J.-W.; Sun, Y.-C.; Chang, W.-T.; Huang, P.-C. Determination of Parabens, Bisphenol A and Its Analogs, Triclosan, and Benzophenone-3 Levels in Human Urine by Isotope-Dilution-UPLC-MS/MS Method Followed by Supported Liquid Extraction. Toxics 2022, 10, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frigerio, G.; Campo, L.; Mercadante, R.; Santos, P.M.; Missineo, P.; Polledri, E.; Fustinoni, S. Development and Validation of a Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry Method to Quantify Metabolites of Phthalates, Including Di-2-Ethylhexyl Terephthalate (DEHTP) and Bisphenol A in Human Urine. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2020, 34, e8796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, M.J.; Park, J.-H.; An, K.-A.; Choi, H.; Kang, Y.; Hwang, M. Quantification of Bisphenols in Korean Urine Using Online Solid-Phase Extraction-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2020, 80, 103491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pia Dima, A.; De Santis, L.; Verlengia, C.; Lombardo, F.; Lenzi, A.; Mazzarino, M.; Botrè, F.; Paoli, D. Development and Validation of a Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry Method for the Simultaneous Determination of Phthalates and Bisphenol a in Serum, Urine and Follicular Fluid. Clin. Mass Spectrom. 2020, 18, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchis, Y.; Coscollà, C.; Yusà, V. Analysis of Four Parabens and Bisphenols A, F, S in Urine, Using Dilute and Shoot and Liquid Chromatography Coupled to Mass Spectrometry. Talanta 2019, 202, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, R.S.; Rocha, B.A.; Rodrigues, J.L.; Barbosa, F. Rapid, Sensitive and Simultaneous Determination of 16 Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals (Parabens, Benzophenones, Bisphenols, and Triclocarban) in Human Urine Based on Microextraction by Packed Sorbent Combined with Liquid Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry (MEPS-LC-MS/MS). Chemosphere 2020, 240, 124951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawaguchi, M.; Ito, R.; Honda, H.; Endo, N.; Okanouchi, N.; Saito, K.; Seto, Y.; Nakazawa, H. Determination of Urinary Triclosan by Stir Bar Sorptive Extraction and Thermal Desorption–Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. B 2008, 875, 577–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geens, T.; Neels, H.; Covaci, A. Sensitive and Selective Method for the Determination of Bisphenol-A and Triclosan in Serum and Urine as Pentafluorobenzoate-Derivatives Using GC–ECNI/MS. J. Chromatogr. B 2009, 877, 4042–4046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, F.; Ikai, Y.; Hayashi, R.; Okumura, M.; Takatori, S.; Nakazawa, H.; Izumi, S.; Makino, T. Determination of Five Phthalate Monoesters in Human Urine Using Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2010, 85, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rastkari, N.; Ahmadkhaniha, R. Magnetic Solid-Phase Extraction Based on Magnetic Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes for the Determination of Phthalate Monoesters in Urine Samples. J. Chromatogr. A 2013, 1286, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.; Song, N.R.; Choi, J.-H.; Lee, J.; Pyo, H. Simultaneous Analysis of Urinary Phthalate Metabolites of Residents in Korea Using Isotope Dilution Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 470–471, 1408–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubwabo, C.; Kosarac, I.; Lalonde, K.; Foster, W.G. Quantitative Determination of Free and Total Bisphenol A in Human Urine Using Labeled BPA Glucuronide and Isotope Dilution Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2014, 406, 4381–4392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzouz, A.; Rascón, A.J.; Ballesteros, E. Simultaneous Determination of Parabens, Alkylphenols, Phenylphenols, Bisphenol A and Triclosan in Human Urine, Blood and Breast Milk by Continuous Solid-Phase Extraction and Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2016, 119, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor-Belda, M.; Bastida, D.; Campillo, N.; Pérez-Cárceles, M.D.; Motas, M.; Viñas, P. A Study of the Influence on Diabetes of Free and Conjugated Bisphenol A Concentrations in Urine: Development of a Simple Microextraction Procedure Using Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2016, 129, 458–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brigante, T.A.V.; Miranda, L.F.C.; de Souza, I.D.; Acquaro Junior, V.R.; Queiroz, M.E.C. Pipette Tip Dummy Molecularly Imprinted Solid-Phase Extraction of Bisphenol A from Urine Samples and Analysis by Gas Chromatography Coupled to Mass Spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. B 2017, 1067, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Ding, E.M.C.; Ding, W.-H. Determination of Parabens in Human Urine by Optimal Ultrasound-Assisted Emulsification Microextraction and on-Line Acetylation Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. B 2017, 1058, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, T. Analytical Method for Urinary Metabolites as Biomarkers for Monitoring Exposure to Phthalates by Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry. Biomed. Chromatogr. 2017, 31, e3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.-H.; Ding, W.-H. Isotope-Dilution Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry Coupled with Injection-Port Butylation for the Determination of 4-t-Octylphenol, 4-Nonylphenols and Bisphenol A in Human Urine. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2018, 149, 572–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correia-Sá, L.; Norberto, S.; Delerue-Matos, C.; Calhau, C.; Domingues, V.F. Micro-QuEChERS Extraction Coupled to GC–MS for a Fast Determination of Bisphenol A in Human Urine. J. Chromatogr. B 2018, 1072, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunha, S.C.; Fernandes, J.O. Quantification of Free and Total Bisphenol A and Bisphenol B in Human Urine by Dispersive Liquid–Liquid Microextraction (DLLME) and Heart-Cutting Multidimensional Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (MD–GC/MS). Talanta 2010, 83, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliani, R.; Naccarato, A.; Malacaria, L.; Tagarelli, A. A Rapid Method for the Quantification of Urinary Phthalate Monoesters: A New Strategy for the Assessment of the Exposure to Phthalate Ester by Solid-phase Microextraction with Gas Chromatography and Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J. Sep. Sci. 2020, 43, 3061–3073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küçük, M.; Osman, B.; Tümay Özer, E. Dummy Molecularly Imprinted Polymer-Based Solid-Phase Extraction Method for the Determination of Some Phthalate Monoesters in Urine by Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry Analysis. J. Chromatogr. A 2024, 1713, 464532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polovkov, N.Y.; Starkova, J.E.; Borisov, R.S. A Simple, Inexpensive, Non-Enzymatic Microwave-Assisted Method for Determining Bisphenol-A in Urine in the Form of Trimethylsilyl Derivative by GC/MS with Single Quadrupole. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2020, 188, 113417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotlarz, N.; McCord, J.; Collier, D.; Lea, C.S.; Strynar, M.; Lindstrom, A.B.; Wilkie, A.A.; Islam, J.Y.; Matney, K.; Tarte, P.; et al. Measurement of Novel, Drinking Water-Associated PFAS in Blood from Adults and Children in Wilmington, North Carolina. Environ. Health Perspect. 2020, 128, 077005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, Q.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y. Simultaneous Determination of Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances and Organophosphorus Flame Retardants in Serum by Ultra-performance Liquid Chromatography/Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2022, 36, e9312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salihović, S.; Dickens, A.M.; Schoultz, I.; Fart, F.; Sinisalu, L.; Lindeman, T.; Halfvarson, J.; Orešič, M.; Hyötyläinen, T. Simultaneous Determination of Perfluoroalkyl Substances and Bile Acids in Human Serum Using Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2019, 412, 2251–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, B.F.; Ahmadireskety, A.; Aristizabal-Henao, J.J.; Bowden, J.A. A Rapid and Simple Method to Quantify Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in Plasma and Serum Using 96-Well Plates. MethodsX 2020, 7, 101111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, S.F.; Isobe, T.; Iwai-Shimada, M.; Kobayashi, Y.; Nishihama, Y.; Taniguchi, Y.; Sekiyama, M.; Michikawa, T.; Yamazaki, S.; Nitta, H.; et al. Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances in Maternal Serum: Method Development and Application in Pilot Study of the Japan Environment and Children’s Study. J. Chromatogr. A 2020, 1618, 460933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurado-Sánchez, B.; Ballesteros, E.; Gallego, M. Analytical Method for Biomonitoring of Perfluoroalkyl Acids in Human Urine. Talanta 2014, 128, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, S.; Brox, J. An Automated High-Throughput SPE Micro-Elution Method for Perfluoroalkyl Substances in Human Serum. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2015, 407, 3751–3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, W.; Kannan, K.; Wu, Q.; Bell, E.M.; Druschel, C.M.; Caggana, M.; Aldous, K.M. Analysis of Polyfluoroalkyl Substances and Bisphenol A in Dried Blood Spots by Liquid Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2013, 405, 4127–4138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poothong, S.; Lundanes, E.; Thomsen, C.; Haug, L.S. High Throughput Online Solid Phase Extraction-Ultra High Performance Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry Method for Polyfluoroalkyl Phosphate Esters, Perfluoroalkyl Phosphonates, and Other Perfluoroalkyl Substances in Human Serum, Plasma, and Whole Blood. Anal. Chim. Acta 2017, 957, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, C.H.; Patel, B.; Palencia, M.; Fan, Z. A Sensitive and Accurate Method for the Determination of Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in Human Serum Using a High Performance Liquid Chromatography-Online Solid Phase Extraction-Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2017, 1480, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosch, C.; Kiranoglu, M.; Fromme, H.; Völkel, W. Simultaneous Quantitation of Perfluoroalkyl Acids in Human Serum and Breast Milk Using On-Line Sample Preparation by HPLC Column Switching Coupled to ESI-MS/MS. J. Chromatogr. B 2010, 878, 2652–2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolomé, M.; Gallego-Picó, A.; Huetos, O.; Lucena, M.Á.; Castaño, A. A Fast Method for Analysing Six Perfluoroalkyl Substances in Human Serum by Solid-Phase Extraction on-Line Coupled to Liquid Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2016, 408, 2159–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luque, N.; Ballesteros-Gómez, A.; van Leeuwen, S.; Rubio, S. A Simple and Rapid Extraction Method for Sensitive Determination of Perfluoroalkyl Substances in Blood Serum Suitable for Exposure Evaluation. J. Chromatogr. A 2012, 1235, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salihovic, S.; Kärrman, A.; Lindström, G.; Lind, P.M.; Lind, L.; van Bavel, B. A Rapid Method for the Determination of Perfluoroalkyl Substances Including Structural Isomers of Perfluorooctane Sulfonic Acid in Human Serum Using 96-Well Plates and Column-Switching Ultra-High Performance Liquid Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2013, 1305, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, L.; Deng, J. Serum Levels of Perfluoroalkyl Acids (PFAAs) with Isomer Analysis and Their Associations with Medical Parameters in Chinese Pregnant Women. Environ. Int. 2014, 64, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salihovic, S.; Dunder, L.; Lind, M.; Lind, L. Assessing the Performance of a Targeted Absolute Quantification Isotope Dilution Liquid Chromatograhy Tandem Mass Spectrometry Assay versus a Commercial Nontargeted Relative Quantification Assay for Detection of Three Major Perfluoroalkyls in Human Blood. J. Mass Spectrom. 2024, 59, e4999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kortenkamp, A. Low Dose Mixture Effects of Endocrine Disrupters: Implications for Risk Assessment and Epidemiology. Int. J. Androl. 2008, 31, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchiandi, J.; Alghamdi, W.; Dagnino, S.; Green, M.P.; Clarke, B.O. Exposure to Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals from Beverage Packaging Materials and Risk Assessment for Consumers. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 465, 133314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calafat, A.M.; Kato, K.; Hubbard, K.; Jia, T.; Botelho, J.C.; Wong, L.-Y. Legacy and Alternative Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in the U.S. General Population: Paired Serum-Urine Data from the 2013–2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Environ. Int. 2019, 131, 105048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafeiadi, M.; Roumeliotaki, T.; Myridakis, A.; Chalkiadaki, G.; Fthenou, E.; Dermitzaki, E.; Karachaliou, M.; Sarri, K.; Vassilaki, M.; Stephanou, E.G.; et al. Association of Early Life Exposure to Bisphenol A with Obesity and Cardiometabolic Traits in Childhood. Environ. Res. 2016, 146, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partington, J.M.; Marchiandi, J.; Szabo, D.; Gooley, A.; Kouremenos, K.; Smith, F.; Clarke, B.O. Validating Blood Microsampling for Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances Quantification in Whole Blood. J. Chromatogr. A 2024, 1713, 464522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carignan, C.C.; Bauer, R.A.; Patterson, A.; Phomsopha, T.; Redman, E.; Stapleton, H.M.; Higgins, C.P. Self-Collection Blood Test for PFASs: Comparing Volumetric Microsamplers with a Traditional Serum Approach. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 7950–7957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panuwet, P.; Hunter, R.E.; D’Souza, P.E.; Chen, X.; Radford, S.A.; Cohen, J.R.; Marder, M.E.; Kartavenka, K.; Ryan, P.B.; Barr, D.B. Biological Matrix Effects in Quantitative Tandem Mass Spectrometry-Based Analytical Methods: Advancing Biomonitoring. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2015, 46, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, R.R. Chapter 20 Protein Precipitation Techniques. Methods Enzymol. 2009, 463, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schummer, C.; Delhomme, O.; Appenzeller, B.; Wennig, R.; Millet, M. Comparison of MTBSTFA and BSTFA in Derivatization Reactions of Polar Compounds Prior to GC/MS Analysis. Talanta 2009, 77, 1473–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadílek, P.; Šatínský, D.; Solich, P. Using Restricted-Access Materials and Column Switching in High-Performance Liquid Chromatography for Direct Analysis of Biologically-Active Compounds in Complex Matrices. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2007, 26, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, C.P. Complementing the Genome with an “Exposome”: The Outstanding Challenge of Environmental Exposure Measurement in Molecular Epidemiology. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2005, 14, 1847–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.W.; Jones, D.P. The Nature of Nurture: Refining the Definition of the Exposome. Toxicol. Sci. 2013, 137, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, O.; Kim, H.L.; Weon, J.-I.; Seo, Y.R. Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals: Review of Toxicological Mechanisms Using Molecular Pathway Analysis. J. Cancer Prev. 2015, 20, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochat, B. From Targeted Quantification to Untargeted Metabolomics: Why LC-High-Resolution-MS Will Become a Key Instrument in Clinical Labs. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2016, 84, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, B.; Deshpande, R.R.; Bird, S.S. Simultaneous Quantitation and Discovery (SQUAD) Analysis: Combining the Best of Targeted and Untargeted Mass Spectrometry-Based Metabolomics. Metabolites 2023, 13, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.-L.; Baesu, A. Influence of Data Acquisition Modes and Data Analysis Approaches on Non-Targeted Analysis of Phthalate Metabolites in Human Urine. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2022, 415, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Sample Preparation | Ionization | BPA, Other Bisphenols | PBs | PEs | TCS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Markham et al., 2010 [58] | Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) | ESI | BPA | - | - | - |

| Fox et al., 2011 [59] | Liquid–Liquid Extraction (LLE) | ESI | BPA | - | - | - |

| Frederiksen et al., 2011 [60] | SPE | ESI | - | 5 | - | - |

| Jeong et al., 2011 [61] | Column Switching | ESI | - | - | 4 | - |

| Solymos et al., 2011 [62] | Dilute and Shoot | ESI | - | - | 3 | - |

| Chen et al., 2012 [63] | SPE | ESI | BPA | - | 5 | - |

| Gries et al., 2012 [64] | LLE | ESI | - | - | 3 | - |

| Liao & Kannan, 2012 [65] | SPE | ESI | BPA | - | - | - |

| Monfort et al., 2012 [66] | LLE | ESI | - | - | 5 | - |

| Nicolucci et al., 2013 [67] | SPE | ESI | BPA | - | - | - |

| Wang et al., 2013 [68] | SPE | ESI | BPA | - | 14 | - |

| Asimakopoulos et al., 2014 [69] | LLE | ESI | - | 7 | - | X |

| Battal et al., 2014 [70] | Protein precipitation | ESI | BPA | |||

| Markham et al., 2014 [71] | SPE | ESI | BPA | - | - | - |

| Moos et al., 2014 [72] | Protein precipitation—Column Switching | ESI | BPA | 9 | - | X |

| Zhou et al., 2014 [73] | SPE | ESI | BPA, 2 others | 4 | - | X |

| Li & Franke, 2015 [74] | LLE | ESI | BPA | - | - | - |

| Myridakis et al., 2015 [9] | SPE | ESI | BPA | 6 | 7 | - |

| Sabaredzovic et al., 2015 [75] | SPE | ESI | - | - | 12 | - |

| Rocha et al., 2016 [76] | Dispersive Liquid–Liquid Microextraction (DLLME) | ESI | BPA, 6 others | - | - | - |

| Wu et al., 2016 [77] | Dual Microextraction | ESI | - | - | 3 | - |

| Heffernan et al., 2016 [78] | SPE | ESI | BPA, 4 others | - | 14 | - |

| Ren et al., 2016 [79] | SPE | ESI | BPA | 5 | - | X |

| Jing et al., 2011 [80] | SPE | ESI | BPA | - | - | - |

| Servaes et al., 2013 [81] | Dilute and Shoot | ESI | - | - | 7 | - |

| Anderson et al., 2014 [82] | LLE | ESI | BPA | - | - | - |

| Dewalque et al., 2014 [83] | SPE | ESI | - | 4 | 7 | - |

| Provencher et al., 2014 [84] | LLE | ESI | BPA | - | - | X |

| Vela-Soria et al., 2014 [85] | DLLME | ESI | BPA, 1 other | 4 | - | - |

| Venisse et al., 2014 [86] | LLE | ESI | BPA | - | - | - |

| Buscher et al., 2015 [87] | SPE | ESI | BPA | - | - | - |

| Cristina Jardim et al., 2015 [88] | Microextraction using Packed Sorbent (MEPS) | ESI | - | 5 | - | - |

| Herrero et al., 2015 [89] | Column switching | ESI | - | - | 9 | - |

| ter Halle et al., 2015 [90] | Organogel materials | APCI | BPA | - | - | - |

| Grignon et al., 2016 [91] | SPE | ESI | BPA | - | - | - |

| Hauck et al., 2016 [92] | SPE | ESI | BPA | - | - | - |

| Schlittenbauer et al., 2016 [93] | Filtration | ESI | - | 8 | - | - |

| Zhou et al., 2018 [94] | Ultrasound-assisted Emulsification Microextraction | ESI | - | 9 | - | - |

| Carrasco-Correa et al., 2015 [95] | DLLME | ESI | - | 4 | - | - |

| Battal et al., 2021 [96] | LLE | ESI | BPA | - | - | - |

| Bocato et al., 2020 [97] | Vortex-assisted DLLME (VADLLME) | ESI | BPA, 6 others | 7 | - | - |

| Chen et al., 2022 [98] | Supported Liquid Extraction (SLE) | ESI | BPA, 2 others | 4 | - | X |

| Frigerio et al., 2020 [99] | SPE | ESI | BPA | - | 7 | - |

| Jo et al., 2020 [100] | Online SPE | ESI | BPA, 2 others | - | - | - |

| Pia Dima et al., 2020 [101] | SPE | ESI | BPA | - | 7 | - |

| Sanchis et al., 2019 [102] | Dilute and Shoot | ESI | BPA, 2 others | 4 | - | - |

| Silveira et al., 2020 [103] | MEPS | ESI | BPA, 3 others | 7 |

| Reference | Sample Preparation | Ionization | BPA, Other Bisphenols | PBs | PEs | TCS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kawaguchi et al., 2008 [104] | Hollow Fiber-Assisted Liquid-phase Microextraction (HF-LPME) | EI | BPA | - | - | - |

| Geens et al., 2009 [105] | SPE followed by Acidified Silica Purification | ECNI | BPA | - | - | X |

| Kondo et al., 2010 [106] | Liquid–Liquid Extraction (LLE) | EI | - | - | 5 | - |

| Gries et al., 2012 [64] | LLE | EI | - | - | 3 | - |

| Rastkari & Ahmadkhaniha, 2013 [107] | Magnetic SPE | EI | - | - | 5 | - |

| Kim et al., 2014 [108] | LLE | EI | - | - | 8 | - |

| Kubwabo et al., 2014 [109] | Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) | EI | BPA | - | - | - |

| Azzouz et al., 2016 [110] | SPE | EI | BPA | 7 | - | X |

| Pastor-Belda et al., 2016 [111] | Dispersive Liquid–Liquid Microextraction (DLLME) | EI | BPA | - | - | - |

| Brigante et al., 2017 [112] | SPE | EI | BPA | - | - | - |

| Hui-Ting et al., 2017 [113] | Optimal Ultrasound-assisted Emulsification Microextraction | EI | - | 4 | - | - |

| Yoshida, 2017 [114] | LLE | EI | - | - | 9 | - |

| Chung & Ding, 2018 [115] | SPE | EI | BPA | - | - | - |

| Correia-Sa et al., 2018 [116] | Micro-Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged and Safe (QuEChERS) | EI | BPA | - | - | - |

| Cunha & Fernandes, 2010 [117] | Dispersive Liquid–Liquid Microextraction (DLLME) | EI | BPA, 1 other | - | - | - |

| Herrero et al., 2015 [89] | LLE | EI | - | - | 9 | - |

| Kawaguchi, Ito, Honda et al., 2008 [104] | Stir Bar Sorptive Extraction (SBSE) | EI | - | - | - | X |

| Elliani et al., 2020 [118] | Solid Phase Microextraction (SPME) | EI | - | - | 7 | - |

| Kucuk et al., 2024 [119] | Dummy molecularly imprinted polymer-based SPE | EI | - | - | 3 | - |

| Polovkov et al., 2020 [120] | LLE | EI | BPA | - | - | - |

| Reference | Sample Preparation | Separation | Ionization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kotlarz et al., 2020 [121] | LLE | UPLC | ESI (Orbi) |

| Li et al., 2022 [122] | LLE | UPLC | ESI (MS/MS) |

| Salihovic et al., 2020 [123] | Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) | UPLC | ESI (MS/MS) |

| Da Silva et al., 2020 [124] | LLE | UPLC | ESI (MS/MS) |

| Nakayama et al., 2020 [125] | LLE + Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) | UPLC | ESI (MS/MS) |

| Jurado-Sanchez et al., 2014 [126] | Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) | GC | EI |

| Huber & Brox, 2015 [127] | Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) | UPLC | ESI (MS/MS) |

| Ma et al., 2013 [128] | LLE | UPLC | ESI (MS/MS) |

| Poothong et al., 2017 [129] | LLE + Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) | UPLC | ESI (MS/MS) |

| Yu et al., 2017 [130] | Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) | HPLC | APCI (MS/MS) |

| Mosch et al., 2010 [131] | Enzymatic hydrolysis + LLE | UPLC | ESI (MS/MS) |

| Bartolome et al., 2016 [132] | Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) | UPLC | ESI (MS/MS) |

| Luque et al., 2012 [133] | SUPRAS-based microextraction | UPLC | ESI (MS/MS) |

| Salihovic et al., 2013 [134] | Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) | UPLC | ESI (MS/MS) |

| Jiang et al., 2014 [135] | Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) | HPLC | ESI (MS/MS) |

| Salihovic et al., 2024 [136] | LLE | UPLC | ESI (MS/MS) |

| Compounds | Ions for LC/MS-MS | Ions for GC/MS-MS (BSTFA Derivatives) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precursor Ion | Product Ion | Precursor Ion | Product Ion | |

| Bisphenols | ||||

| BPA | 227.2 | 212.2 | 372.0 | 357.0 |

| Dansylated BPA | 695.5 | 171.1 | - | - |

| BPS | 248.9 | 108.0 | n.a. | n.a. |

| BPF | 199.0 | 93.2 | n.a. | n.a. |

| BPZ | 267.1 | 173.0 | n.a. | n.a. |

| BPP | 345.1 | 330.0 | n.a. | n.a. |

| BPAF | 335.0 | 265.9 | n.a. | n.a. |

| BPAP | 289.1 | 273.9 | n.a. | n.a. |

| Phthalates | ||||

| mEP | 193.1 | 92.1 | n.a. | n.a. |

| mnBP/miBP | 221.1 | 77.1 | n.a. | n.a. |

| mBzP | 255.2 | 105.1 | n.a. | n.a. |

| mEHHP | 293.2 | 121.1 | n.a. | n.a. |

| mEOHP | 291.2 | 121.1 | n.a. | n.a. |

| mEHP | 277.2 | 134.1 | n.a. | n.a. |

| Parabens | ||||

| MPB | 151.1 | 92.1 | 224.0 | 209.0 |

| EPB | 165.1 | 92.1 | 238.0 | 223.0 |

| nPPB/isoPPB | 179.1 | 92.1 | 252.0 | 237.0 |

| nBPB/isoBPB | 193.1 | 92.1 | 266.0 | 251.0 |

| BeP | 227.0 | 92.0 | n.a. | n.a. |

| PeP | 207.0 | 92.0 | n.a. | n.a. |

| HeP | 235.0 | 92.0 | n.a. | n.a. |

| Antimicrobials | ||||

| Triclosan | 287.0 | 35.0 | 362.0 | 347.0 |

| PFAS | ||||

| PFCAs | 213.0–913.0 | 99.0–868.0 | n.a. | n.a. |

| PFSAs | 449.0–526.0 | 80.0–99.0 | n.a. | n.a. |

| FASAs | 512.0–526.0 | 169.0–219.0 | n.a. | n.a. |

| FTS | 327.0–789.0 | 81.0–307.0 | n.a. | n.a. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chatziioannou, A.C.; Myridakis, A.; Stephanou, E.G. Biomonitoring of Environmental Phenols, Phthalate Metabolites, Triclosan, and Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in Humans with Chromatography and Mass Spectrometry. Toxics 2025, 13, 1029. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121029

Chatziioannou AC, Myridakis A, Stephanou EG. Biomonitoring of Environmental Phenols, Phthalate Metabolites, Triclosan, and Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in Humans with Chromatography and Mass Spectrometry. Toxics. 2025; 13(12):1029. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121029

Chicago/Turabian StyleChatziioannou, Anastasia Chrysovalantou, Antonis Myridakis, and Euripides G. Stephanou. 2025. "Biomonitoring of Environmental Phenols, Phthalate Metabolites, Triclosan, and Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in Humans with Chromatography and Mass Spectrometry" Toxics 13, no. 12: 1029. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121029

APA StyleChatziioannou, A. C., Myridakis, A., & Stephanou, E. G. (2025). Biomonitoring of Environmental Phenols, Phthalate Metabolites, Triclosan, and Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in Humans with Chromatography and Mass Spectrometry. Toxics, 13(12), 1029. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics13121029