Physico-Chemical, Microbiological and Sensory Evaluation of Ready-to-Use Vegetable Pâté Added with Olive Leaf Extract

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials

2.2. Chemicals

2.3. Formulation and Manufacture of Olive-Based Pâté

2.4. Microbiological Analyses

2.5. Physico-Chemical Analyses

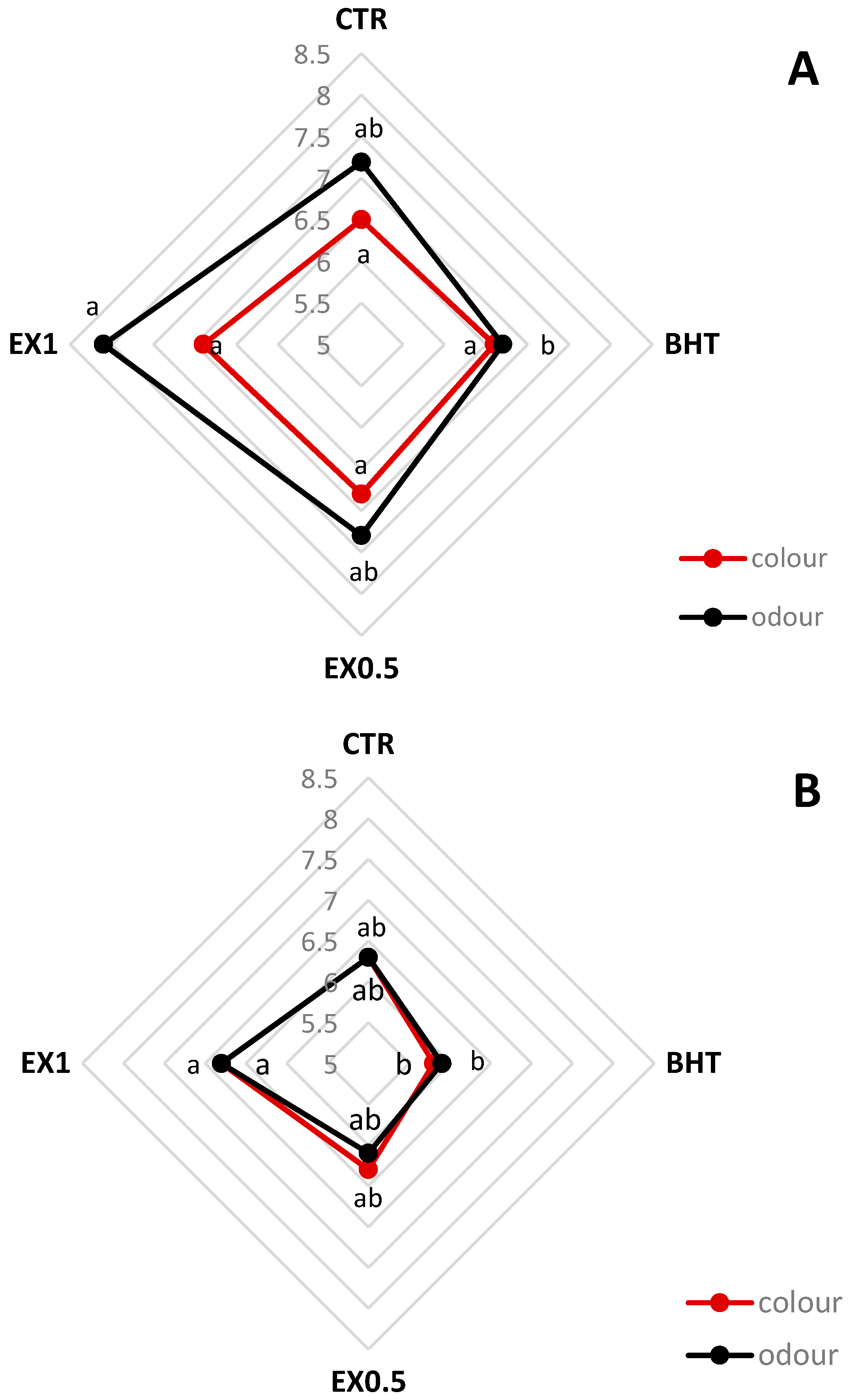

2.6. Sensory Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

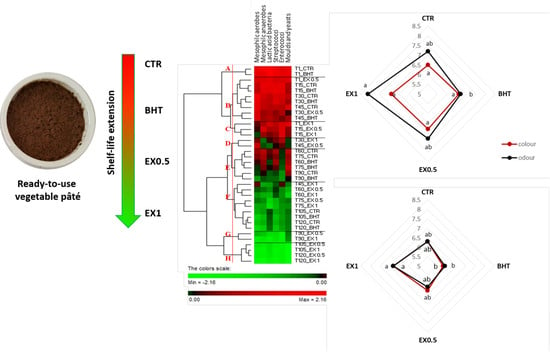

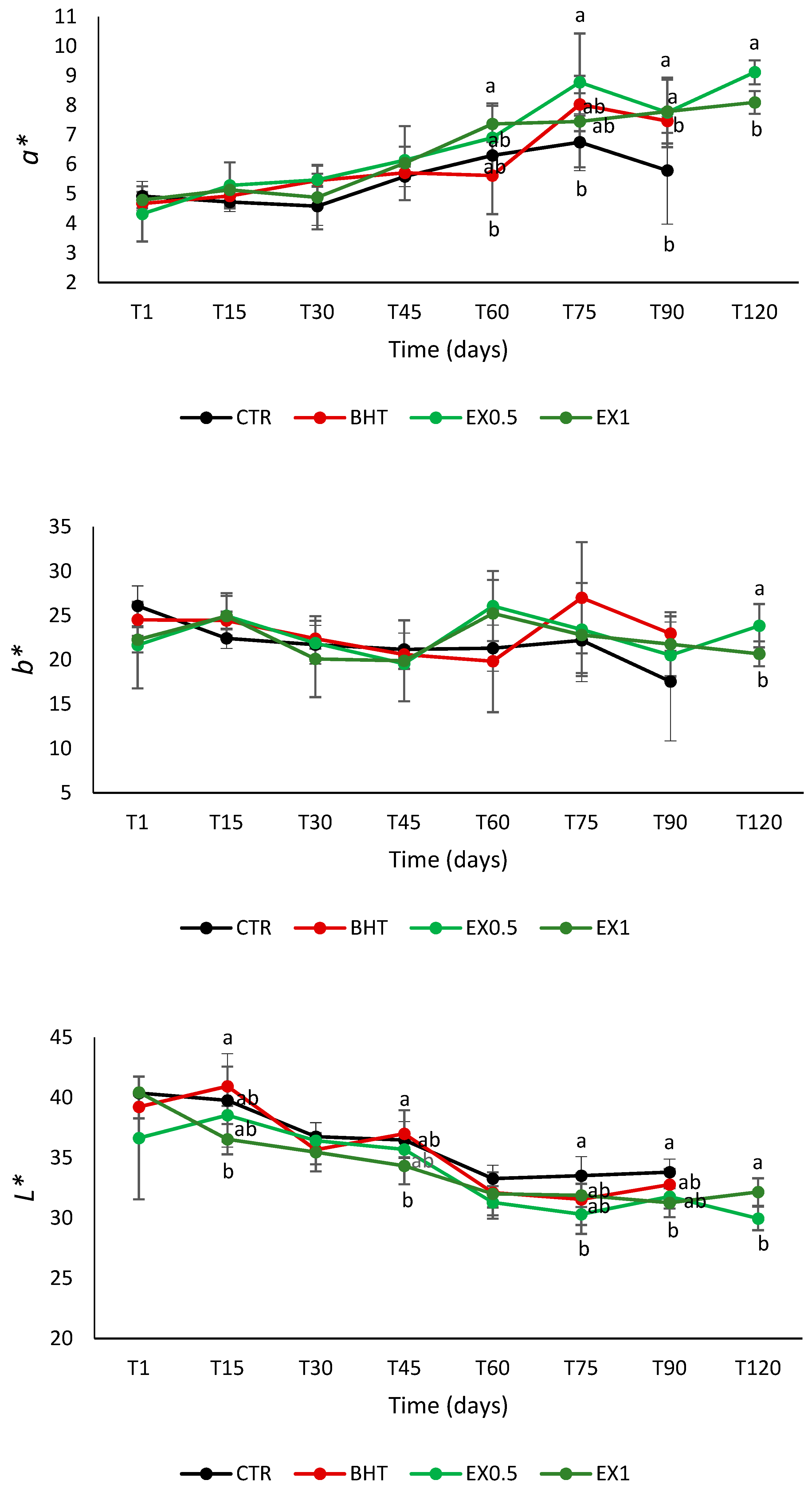

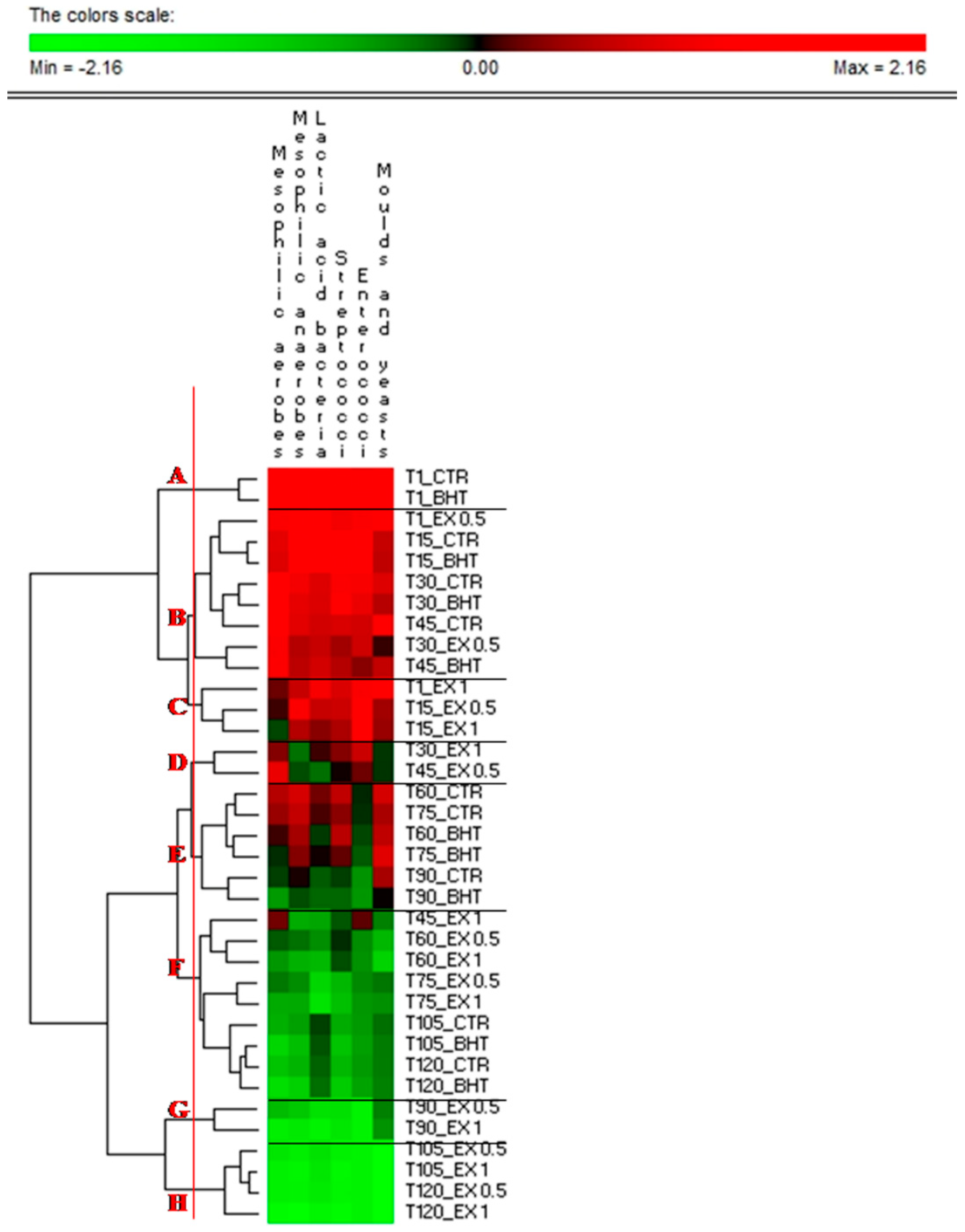

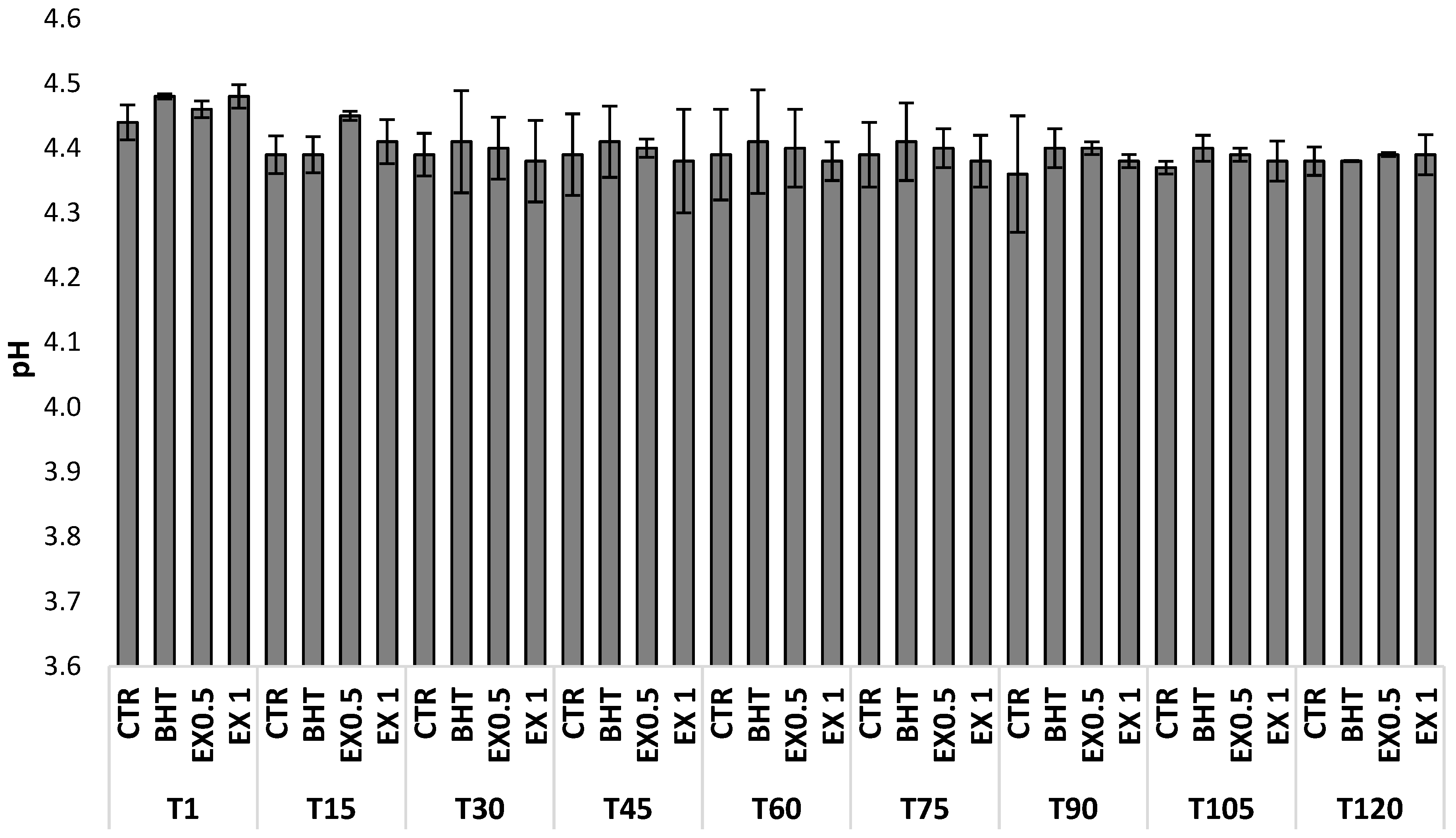

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Labuza, T.P.; Szybist, L.M. Open Dating of Foods; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United States. Available online: http://www.fao.org/food-loss-and-food-waste/en/ (accessed on 21 March 2019).

- Stuart, D. Constrained choice and ethical dilemmas in land management: Environmental quality and food safety in California agriculture. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2009, 22, 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkling-Ribeiro, M.; Noci, F.; Cronin, D.A.; Lyng, J.G.; Morgan, D.J. Shelf life and sensory evaluation of orange juice after exposure to thermosonication and pulsed electric fields. Food Bioprod. Process 2009, 87, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umemura, T.; Kodama, Y.; Hioki, K.; Inoue, T.; Nomura, T.; Kurokawa, Y. Butylhydroxytoluene (BHT) increases susceptibility of transgenic rasH2 mice to lung carcinogenesis. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2001, 127, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, A.K.; Dwyer-Nield, L.D.; Hankin, J.A.; Murphy, R.C.; Malkinson, A.M. The lung tumor promoter, butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT), causes chronic inflammation in promotion-sensitive BALB/cByJ mice but not in promotion-resistant CXB4 mice. Toxicology 2001, 169, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanishlieva, N.V.; Marinova, E.M. Stabilisation of edible oils with natural antioxidants. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Tech. 2001, 103, 752–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calo, J.R.; Crandall, P.G.; O’Bryan, C.A.; Ricke, S.C. Essential oils as antimicrobials in food systems–A review. Food Control 2015, 54, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, J.M.; Sineiro, J.; Amado, I.R.; Franco, D. Influence of natural extracts on the shelf life of modified atmosphere-packaged pork patties. Meat Sci. 2014, 96, 526–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabera, J.; Guinda, Á.; Ruiz-Rodríguez, A.; Señoráns, F.J.; Ibáñez, E.; Albi, T.; Reglero, G. Countercurrent supercritical fluid extraction and fractionation of high-added-value compounds from a hexane extract of olive leaves. J Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 4774–4779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Difonzo, G.; Russo, A.; Trani, A.; Paradiso, V.M.; Ranieri, M.; Pasqualone, A.; Summo, C.; Silletti, R.; Tamma, G.; Caponio, F. Green extracts from Coratina olive cultivar leaves: Antioxidant characterization and biological activity. J. Funct. Food 2017, 31, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; McKeever, L.C.; Malik, N.S. Assessment of the antimicrobial activity of olive leaf extract against foodborne bacterial pathogens. Front Microbiol. 2017, 8, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paiva-Martins, F.; Correia, R.; Félix, S.; Ferreira, P.; Gordon, M.H. Effects of enrichment of refined olive oil with phenolic compounds from olive leaves. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 4139–4143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farag, R.S.; Mahmoud, E.A.; Basuny, A.M. Use crude olive leaf juice as a natural antioxidant for the stability of sunflower oil during heating. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2007, 42, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouaziz, M.; Fki, I.; Jemai, H.; Ayadi, M.; Sayadi, S. Effect of storage on refined and husk olive oils composition: Stabilization by addition of natural antioxidants from Chemlali olive leaves. Food Chem. 2008, 108, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalas, S.; Athanasiadis, V.; Gortzi, O.; Bounitsi, M.; Giovanoudis, I.; Tsaknis, J.; Bogiatzis, F. Enrichment of table olives with polyphenols extracted from olive leaves. Food Chem. 2011, 127, 1521–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caponio, F.; Difonzo, G.; Calasso, M.; Cosmai, L.; De Angelis, M. Effects of olive leaf extract addition on fermentative and oxidative processes of table olives and their nutritional properties. Food Res. Int. 2019, 116, 1306–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, J.E.; Stepanyan, V.; Allen, P.; O’grady, M.N.; O’brien, N.M.; Kerry, J.P. The effect of lutein, sesamol, ellagic acid and olive leaf extract on lipid oxidation and oxymyoglobin oxidation in bovine and porcine muscle model systems. Meat Sci. 2009, 83, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, J.E.; Allen, P.; Brunton, N.; O’grady, M.N.; Kerry, J.P. Phenolic composition and in vitro antioxidant capacity of four commercial phytochemical products: Olive leaf extract (Olea europaea L.), lutein, sesamol and ellagic acid. Food Chem. 2011, 126, 948–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.M.; Rabii, N.S.; Garbaj, A.M.; Abolghait, S.K. Antibacterial effect of olive (Olea europaea L.) leaves extract in raw peeled undeveined shrimp (Penaeus semisulcatus). Int. J. Vet. Sci. Med. 2014, 2, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Difonzo, G.; Pasqualone, A.; Silletti, R.; Cosmai, L.; Summo, C.; Paradiso, V.M.; Caponio, F. Use of olive leaf extract to reduce lipid oxidation of baked snacks. Food Res. Int. 2018, 108, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosmai, L.; Caponio, F.; Pasqualone, A.; Paradiso, V.M.; Summo, C. Evolution of the oxidative stability, bio-active compounds and colour characteristics of non-thermally treated vegetable pâtés during frozen storage. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2017, 97, 4904–4911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosmai, L.; Caponio, F.; Summo, C.; Paradiso, V.M.; Cassone, A.; Pasqualone, A. New formulations of olive-based pâtés: Development and quality. Ital. J. Food Sci. 2017, 29, 302–316. [Google Scholar]

- Cosmai, L.; Campanella, D.; Summo, C.; Paradiso, V.M.; Pasqualone, A.; De Angelis, M.; Caponio, F. Combined effects of a natural Allium spp. extract and modified atmospheres packaging on shelf life extension of olive-based paste. Int. J. Food Sci. Tech. 2017, 52, 1164–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caponio, F.; Squeo, G.; Brunetti, L.; Pasqualone, A.; Summo, C.; Paradiso, V.M.; Catalano, P.; Bianchi, B. Influence of the feed pipe position of an industrial scale two-phase decanter on extraction efficiency and chemical-sensory characteristics of virgin olive oil. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 4279–4286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabiano, B.; Perego, P.; Pastorino, R.; Del Borghi, M. The extension of the shelf-life of ‘pesto’ sauce by a combination of modified atmosphere packaging and refrigeration. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2000, 35, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caraux, G.; Pinloche, S. PermutMatrix: A graphical environment to arrange gene expression profiles in optimal linear order. Bioinformatics 2004, 21, 1280–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limbo, S.; Uboldi, E.; Adobati, A.; Iametti, S.; Bonomi, F.; Mascheroni, E.; Santagostino, S.; Powers, T.H.; Franzetti, L.; Piergiovanni, L. Shelf life of case-ready beef steaks (Semitendinosus muscle) stored in oxygen-depleted master bag system with oxygen scavengers and CO2/N2 modified atmosphere packaging. Meat Sci. 2013, 93, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zardetto, S. Effect of temperature and modified atmosphere on the growth of Penicillium aurantiogriseum isolated from fresh filled pasta. Tec. Molit. 2004, 55, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanguinetti, A.M.; Del Caro, A.; Mangia, N.P.; Secchi, N.; Catzeddu, P.; Piga, A. Quality changes of fresh filled pasta during storage: Influence of modified atmosphere packaging on microbial growth and sensory properties. Food Sci. Tech. Int. 2011, 17, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, A.K.; Chatli, M.K.; Kumar, D.; Kumar, P.; Mehta, N. Efficacy of sweet potato powder and added water as fat replacer on the quality attributes of low-fat pork patties. Asian-Australas J. Anim. Sci. 2015, 28, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thielmann, J.; Kohnen, S.; Hauser, C. Antimicrobial activity of Olea europaea Linne extracts and their applicability as natural food preservative agents. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2017, 251, 48–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gök, V.; Bor, Y. Effect of olive leaf, blueberry and Zizyphus jujuba extracts on the quality and shelf life of meatball during storage. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2012, 10, 190–195. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, J.E.; Stepanyan, V.; Allen, P.; O’grady, M.N.; Kerry, J.P. Effect of lutein, sesamol, ellagic acid and olive leaf extract on the quality and shelf-life stability of packaged raw minced beef patties. Meat Sci. 2010, 84, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, M.; García, L.A.; Díaz, M. Volatile compounds in cider: Inoculation time and fermentation temperature effects. J. Inst. Brew. 2006, 112, 210–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas, J.J. Characterization of alcohol acyltransferase from olive fruit. J. Agr. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 3155–3158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatini, N.; Marsilio, V. Volatile compounds in table olives (Olea Europaea L., Nocellara del Belice cultivar). Food Chem. 2008, 107, 1522–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raitio, R.; Orlien, V.; Skibsted, L.H. Effects of palm oil quality and packaging on the storage stability of dry vegetable bouillon paste. Food Chem. 2012, 132, 1324–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Time | Samples Code | Mesophilic Aerobes | Mesophilic Anaerobes | Lactic Acid Bacteria | Streptococci | Enterococci | Moulds and Yeasts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | CTR | 5.98 ± 0.15 a | 6.04 ± 0.27 a | 6.55 ± 0.14 a | 6.19 ± 0.14 a | 5.15 ± 0.13 ab | 5.26 ± 0.27 a |

| BHT | 5.92 ± 0.24 a | 5.88 ± 0.14 ab | 6.49 ± 0.19 b | 6.16 ± 0.12 a | 5.28 ± 0.27 a | 5.19 ± 0.14 a | |

| EX0.5 | 5.82 ± 0.23 a | 5.81 ± 0.15 ab | 6.07 ± 0.28 b | 5.76 ± 0.16 b | 4.82 ± 0.26 bc | 4.98 ± 0.22 b | |

| EX1 | 5.40 ± 0.16 b | 5.57 ± 0.15 ab | 5.94 ± 0.15 b | 5.56 ± 0.18 bc | 4.83 ± 0.22 bc | 5.06 ± 0.10 b | |

| T15 | CTR | 5.71 ± 0.13 ab | 5.89 ± 0.26 b | 6.11 ± 0.26 a | 5.96 ± 0.15 ab | 5.27 ± 0.19 a | 4.05 ± 0.15 d |

| BHT | 5.68 ± 0.08 ab | 5.84 ± 0.11 ab | 6.05 ± 0.13 b | 6.04 ± 0.13 ab | 5.16 ± 0.11 ab | 3.99 ± 0.16 d | |

| EX0.5 | 5.35 ± 0.12 bc | 5.78 ± 0.13 b | 5.67 ± 0.12 c | 5.47 ± 0.14 c | 4.98 ± 0.11 b | 3.74 ± 0.16 de | |

| EX1 | 5.26 ± 0.18 bc | 5.52 ± 0.27 b | 5.46 ± 0.13 cd | 5.31 ± 0.15 c | 4.99 ± 0.21 b | 3.66 ± 0.09 e | |

| T30 | CTR | 6.01 ± 0.13 a | 5.74 ± 0.14 b | 5.78 ± 0.11 c | 5.81 ± 0.13 b | 4.76 ± 0.1 bc | 4.34 ± 0.19 c |

| BHT | 5.92 ± 0.16 a | 5.68 ± 0.28 b | 5.76 ± 0.02 c | 5.88 ± 0.09 b | 4.51 ± 0.11 c | 3.91 ± 0.13 d | |

| EX0.5 | 5.82 ± 0.11 a | 5.52 ± 0.13 b | 5.67 ± 0.06 c | 5.27 ± 0.3 cd | 4.04 ± 0.09 d | 3.22 ± 0.07 f | |

| EX1 | 5.44 ± 0.21 b | 5.18 ± 0.11 c | 5.33 ± 0.01 cd | 5.17 ± 0.5 cd | 3.99 ± 0.08 d | 3.02 ± 0.06 fg | |

| T45 | CTR | 5.91 ± 0.03 a | 5.67 ± 0.13 b | 5.71 ± 0.27 c | 5.55 ± 0.13 bc | 4.08 ± 0.09 d | 4.85 ± 0.17 b |

| BHT | 5.83 ± 0.15 a | 5.54 ± 0.27 b | 5.72 ± 0.13 c | 5.35 ± 0.12 c | 3.35 ± 0.06 e | 4.02 ± 0.09 d | |

| EX0.5 | 5.74 ± 0.02 ab | 5.24 ± 0.02 c | 5.12 ± 0.25 d | 4.96 ± 0.09 de | 3.17 ± 0.07 ef | 3.03 ± 0.06 fg | |

| EX1 | 5.41 ± 0.26 b | 5.03 ± 0.08 cd | 4.92 ± 0.13 de | 4.82 ± 0.08 de | 3.08 ± 0.11 f | 2.61 ± 0.06 g | |

| T60 | CTR | 5.55 ± 0.24 b | 5.62 ± 0.12 b | 5.41 ± 0.08 cd | 5.41 ± 0.12 c | 2.75 ± 0.14 fg | 4.21 ± 0.09 c |

| BHT | 5.35 ± 0.05 bc | 5.48 ± 0.06 bc | 5.23 ± 0.07 d | 5.37 ± 0.13 c | 2.61 ± 0.12 g | 3.98 ± 0.09 d | |

| EX0.5 | 5.23 ± 0.23 bc | 5.18 ± 0.11 c | 5.02 ± 0.12 de | 4.91 ± 0.12 de | 2.08 ± 0.09 h | 2.04 ± 0.04 i | |

| EX1 | 5.09 ± 0.17 c | 5.01 ± 0.11 cd | 4.82 ± 0.06 de | 4.84 ± 0.18 de | 2.02 ± 0.04 h | 1.60 ± 0.08 l | |

| T75 | CTR | 5.48 ± 0.06 b | 5.56 ± 0.13 b | 5.34 ± 0.25 cd | 5.19 ± 0.12 cd | 2.71 ± 0.06 fg | 3.80 ± 0.11 de |

| BHT | 5.29 ± 0.01 bc | 5.42 ± 0.23 bc | 5.29 ± 0.09 d | 5.08 ± 0.12 d | 2.51 ± 0.05 g | 4.36 ± 0.07 c | |

| EX0.5 | 5.17 ± 0.11 bc | 5.12 ± 0.08 cd | 4.63 ± 0.13 e | 4.37 ± 0.11 ef | 2.11 ± 0.04 h | 2.68 ± 0.01 g | |

| EX1 | 5.03 ± 0.22 c | 5.04 ± 0.01 cd | 4.51 ± 0.14 e | 4.32 ± 0.05 ef | 1.96 ± 0.08 h | 2.49 ± 0.09 h | |

| T90 | CTR | 5.27 ± 0.09 bc | 5.31 ± 0.01 c | 5.17 ± 0.01 d | 4.88 ± 0.13 de | 2.01 ± 0.20 h | 3.77 ± 0.08 de |

| BHT | 5.08 ± 0.01 c | 5.24 ± 0.09 c | 5.14 ± 0.09 d | 4.77 ± 0.12 e | 1.96 ± 0.15 h | 3.14 ± 0.07 f | |

| EX0.5 | 4.96 ± 0.11 c | 4.91 ± 0.11 d | 4.52 ± 0.12 e | 4.01 ± 0.08 fg | <1l ** | 2.62 ± 0.02 g | |

| EX1 | 4.63 ± 0.08 d | 4.73 ± 0.21 de | 4.31 ± 0.11 f | 3.92 ± 0.11 fg | <1l | 2.45 ± 0.04 h | |

| T105 | CTR | 5.01 ± 0.11 c | 5.07 ± 0.16 cd | 5.22 ± 0.11 d | 4.46 ± 0.13 e | 1.95 ± 0.04 h | 2.74 ± 0.06 g |

| BHT | 4.83 ± 0.09 cd | 4.96 ± 0.14 d | 5.18 ± 0.08 d | 4.28 ± 0.14 f | 1.87 ± 0.03 i | 2.66 g | |

| EX0.5 | 4.72 ± 0.22 cd | 4.69 ± 0.10 de | 4.52 ± 0.03 e | 3.74 ± 0.09 g | <1l | <1 m | |

| EX1 | 4.61 ± 0.07 d | 4.58 ± 0.10 e | 4.47 ± 0.05e f | 3.61 ± 0.08 g | <1l | <1 m | |

| T120 | CTR | 4.92 ± 0.02 c | 5.00 ± 0.00 cd | 5.15 ± 0.02 d | 4.38 ± 0.05 ef | 1.93 h | 2.65 ± 0.026 g |

| BHT | 4.77 ± 0.02 cd | 4.88 ± 0.02 d | 5.12 ± 0.05 d | 4.22 ± 0.09 f | 1.81 i | 2.61 ± 0.044 g | |

| EX0.5 | 4.61 ± 0.01 d | 4.63 ± 0.02 de | 4.43 ± 0.02 ef | 3.68 ± 0.07 g | <1l | <1 m | |

| EX1 | 4.48 ± 0.01 e | 4.46 ± 0.02 e | 4.29 ± 0.00 f | 3.55 ± 0.04 g | <1l | <1 m |

| Volatile Compounds | CTR | BHT | EX0.5 | EX1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aldehydes and ketones | ||||

| 2-Propenal | 10.31 ± 1.55 b | 20.17 ± 0.78 a | 15.69 ± 3.46 ab | 21.12 ± 5.06 a |

| 2-Methylbutanal | 3.73 ± 0.63 c | 8.20 ± 0.36 b | 10.64 ± 0.61 a | 12.07 ± 1.17 a |

| 3-Methylbutanal | 6.18 ± 1.30 b | 15.03 ± 1.43 ab | 19.27 ± 0.89 ab | 23.21 ± 2.27 a |

| Hexanal | 2.12 ± 0.22 b | 3.76 ± 0.75 ab | 6.18 ± 0.41 ab | 6.58 ± 1.21 a |

| 2-(E)-Hexenal | 0.65 ± 0.18 ab | 0.38 ± 0.04 b | 0.94 ± 0.54 a | 0.57 ± 0.07 ab |

| 2-(E)-Heptenal | 0.89 ± 0.02 c | 1.59 ± 0.37 b | 3.59 ± 1.18 a | 3.29 ± 0.36 a |

| Nonanal | 1.06 ± 0.06 a | 0.75 ± 0.14 b | 1.01 ± 0.08 a | 0.88 ± 0.08 a |

| 2-Butanone | 530.92 ± 21.19 | 568.68 ± 24.63 | 555.29 ± 28.55 | 593.65 ± 23.08 |

| Benzaldehyde | 1.22 ± 0.42 | 1.29 ± 0.27 | 1.39 ± 0.14 | 1.25 ± 0.45 |

| Benzeneacetaldehyde | 2.30 ± 1.66 | 2.33 ± 0.84 | 2.42 ± 0.79 | 4.78 ± 0.68 |

| Esters | ||||

| Ethyl acetate | 62.26 ± 6.43 b | 70.69 ± 2.79 b | 111.78 ± 10.80 a | 110.12 ± 2.05 a |

| n-Propyl acetate | 30.40 ± 7.50 | 42.19 ± 6.58 | 45.37 ± 4.33 | 41.46 ± 7.19 |

| Alcohols | ||||

| Ethyl alcohol | 96.65 ± 1.35 b | 117.50 ± 9.39 b | 186.76 ± 17.02 a | 193.77 ± 22.77 a |

| 2-Butanol | 252.27 ± 6.12 | 248.71 ± 13.48 | 236.95 ± 30.81 | 218.16 ± 9.33 |

| Acids | ||||

| Acetic acid | 249.85 ± 79.21 | 186.99 ± 52.01 | 249.20 ± 33.23 | 240.28 ± 35.91 |

| Propanoic acid | 29.74 ± 7.89 | 19.87 ± 1.32 | 31.01 ± 1.24 | 22.91 ± 0.89 |

| Butanoic acid | 0.77 ± 0.10 b | 0.98 ± 0.18 ab | 1.29 ± 0.16 a | 1.05 ± 0.11 ab |

| Hexanoic acid | 2.88 ± 0.09 a | 2.78 ± 0.10 a | 1.60 ± 0.24 b | 1.24 ± 0.05 b |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Difonzo, G.; Squeo, G.; Calasso, M.; Pasqualone, A.; Caponio, F. Physico-Chemical, Microbiological and Sensory Evaluation of Ready-to-Use Vegetable Pâté Added with Olive Leaf Extract. Foods 2019, 8, 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods8040138

Difonzo G, Squeo G, Calasso M, Pasqualone A, Caponio F. Physico-Chemical, Microbiological and Sensory Evaluation of Ready-to-Use Vegetable Pâté Added with Olive Leaf Extract. Foods. 2019; 8(4):138. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods8040138

Chicago/Turabian StyleDifonzo, Graziana, Giacomo Squeo, Maria Calasso, Antonella Pasqualone, and Francesco Caponio. 2019. "Physico-Chemical, Microbiological and Sensory Evaluation of Ready-to-Use Vegetable Pâté Added with Olive Leaf Extract" Foods 8, no. 4: 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods8040138

APA StyleDifonzo, G., Squeo, G., Calasso, M., Pasqualone, A., & Caponio, F. (2019). Physico-Chemical, Microbiological and Sensory Evaluation of Ready-to-Use Vegetable Pâté Added with Olive Leaf Extract. Foods, 8(4), 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods8040138