Rice Bran-Derived Peptides with Antioxidant Activity: Effects of Enzymatic Hydrolysis Using Bacillus licheniformis and α-Chymotrypsin

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of Rice Bran Protein, Protein Hydrolysates, and Peptide Fractions

2.3. Physicochemical Characterization

2.3.1. Color Attributes

2.3.2. Degree of Hydrolysis

2.3.3. Protein Content

2.3.4. Surface Hydrophobicity

2.3.5. Molecular Weight Distribution

2.3.6. Secondary Structure Analysis

2.4. Total Phenolic Content

2.5. Antioxidant Activity Assays

2.5.1. ABTS Radical Scavenging Activity

2.5.2. DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity

2.5.3. Metal Chelating Activity

2.5.4. Linoleic Peroxidation Inhibition Assay

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characteristics of Rice Bran Protein, Rice Bran Hydrolysates, and Peptide Fractions

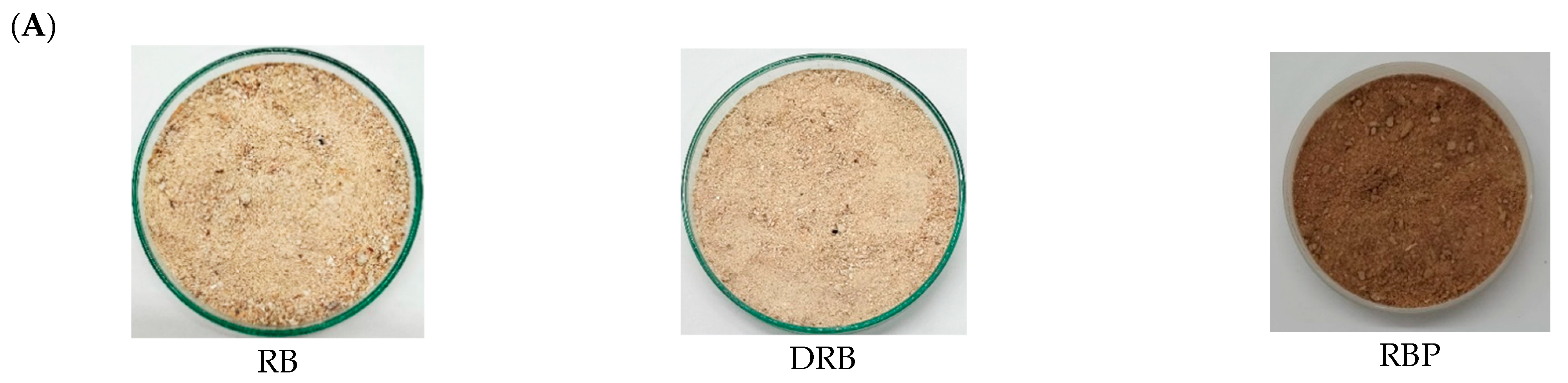

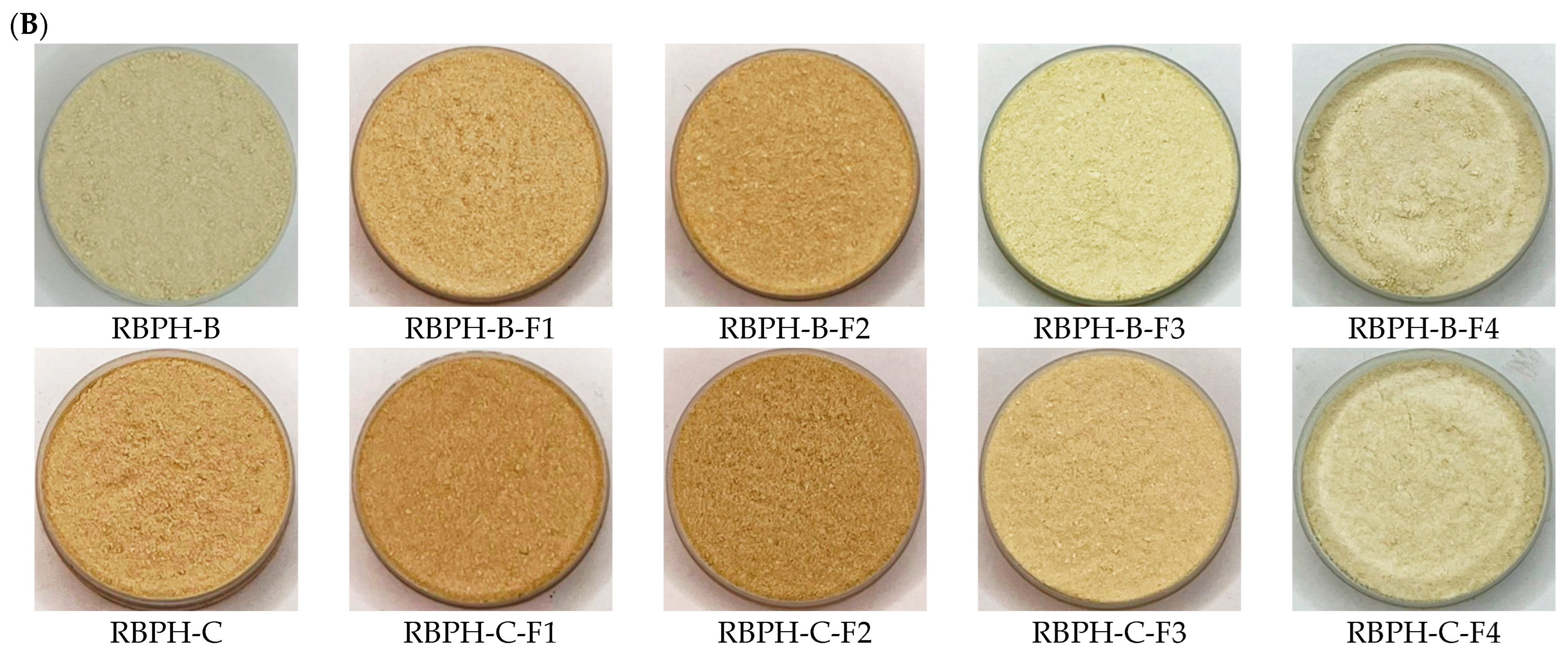

3.1.1. Color Characteristics

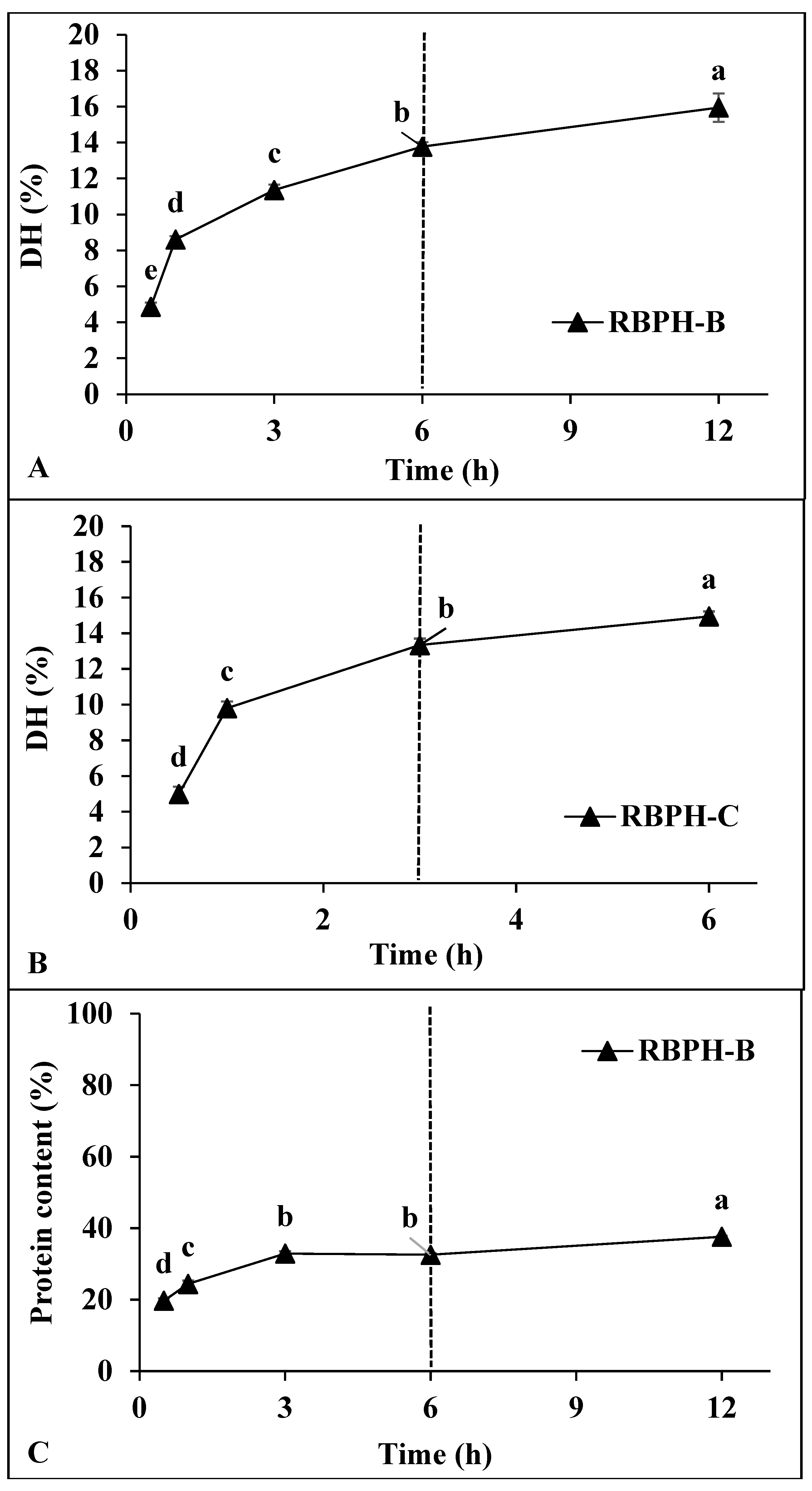

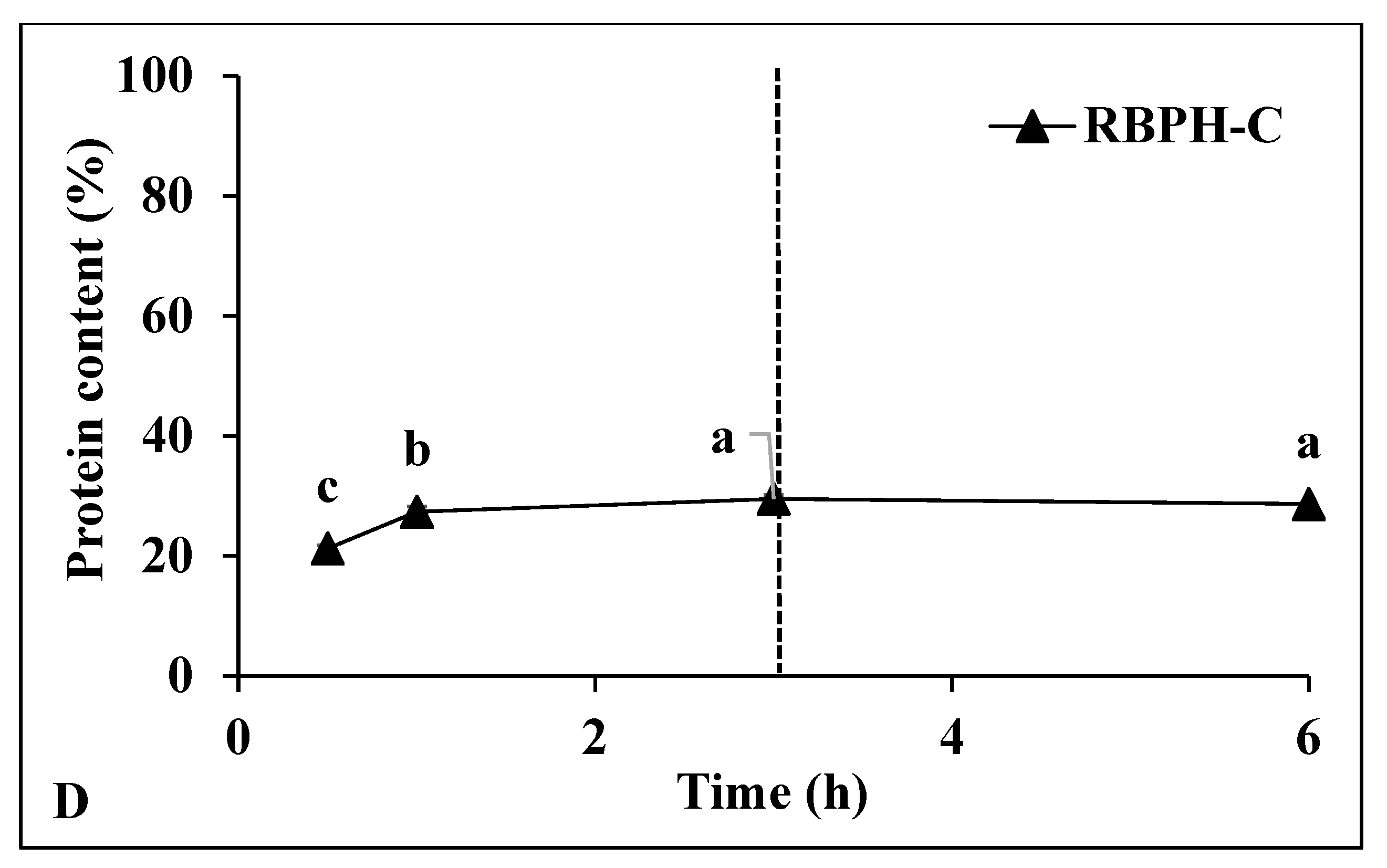

3.1.2. Degree of Hydrolysis and Protein Content

3.1.3. Surface Hydrophobicity

3.1.4. SDS-PAGE Analysis

3.1.5. Protein Secondary Structures

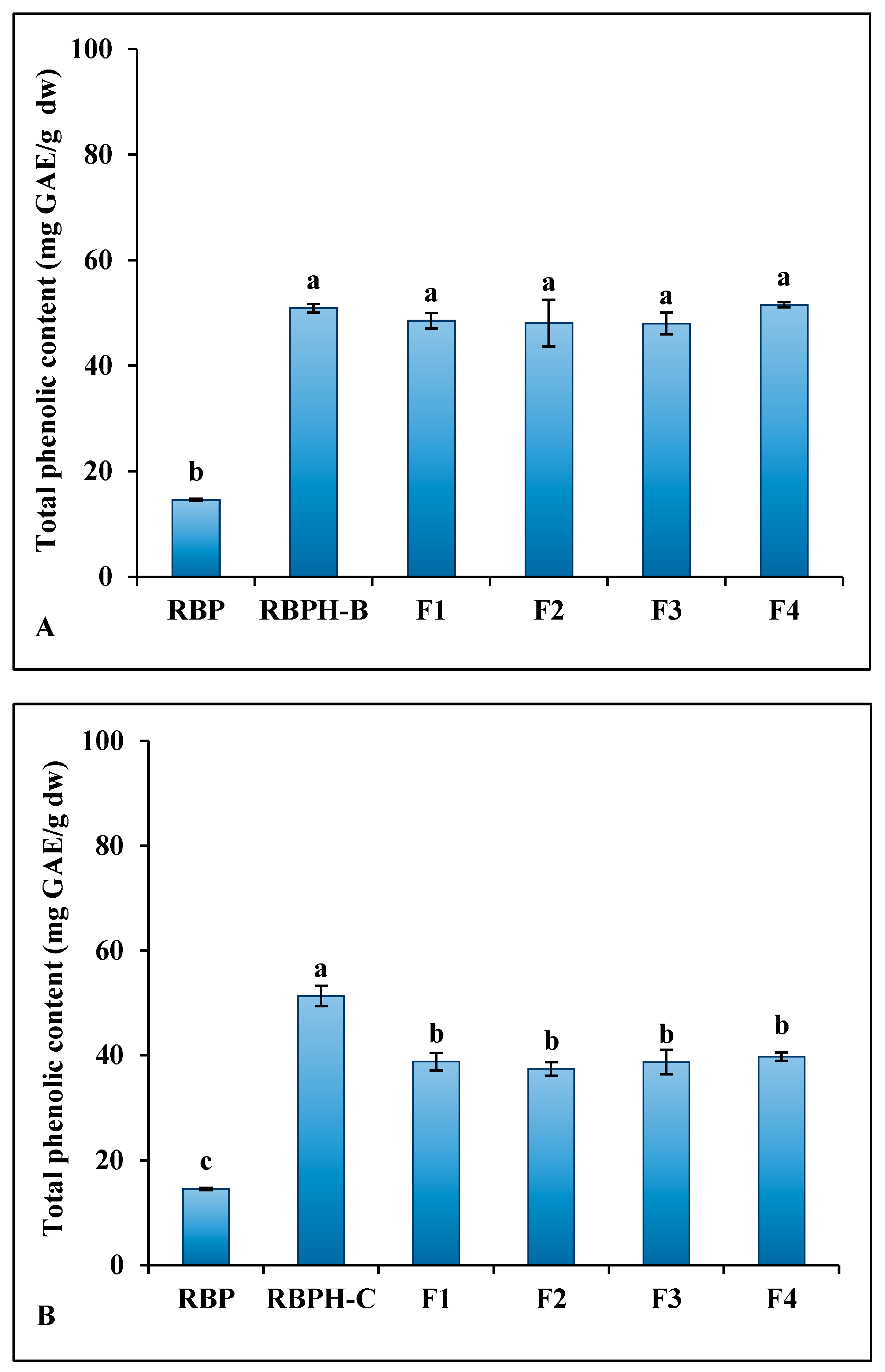

3.2. Total Phenolic Content

3.3. Antioxidant Properties

3.3.1. ABTS Radical Scavenging Activity

3.3.2. DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity

3.3.3. Metal Chelating Activity

3.3.4. Lipid Peroxidation Inhibition Activity

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Singh, T.P.; Siddiqi, R.A.; Sogi, D.S. Enzymatic modification of rice bran protein: Impact on structural, antioxidant and functional properties. LWT 2021, 138, 110648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, P.; Moosavi-Nasab, M.; Mirzapour-Kouhdasht, A.; Khalesi, M. Generation of hydrolysates from rice bran proteins using a combined ultrasonication-Alcalase hydrolysis treatment. Food Biosci. 2021, 42, 101110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phongthai, S.; D’Amico, S.; Schoenlechner, R.; Homthawornchoo, W.; Rawdkuen, S. Fractionation and antioxidant properties of rice bran protein hydrolysates stimulated by in vitro gastrointestinal digestion. Food Chem. 2018, 240, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najafian, L.; Babji, A.S. Production of bioactive peptides using enzymatic hydrolysis and identification antioxidative peptides from patin (Pangasius sutchi) sarcoplasmic protein hydolysate. J. Funct. Foods 2014, 9, 280–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noptana, R.; McClements, D.J.; McLandsborough, L.A.; Onsaard, E. Comparison of characteristics and antioxidant activities of sesame protein hydrolysates and their fractions. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onsaard, W.; Kate-Ngam, S.; Onsaard, E. Physicochemical and antioxidant properties of rice bran protein hydrolysates obtained from different proteases. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2023, 17, 2374–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, S.F.; Pouliot, Y. Functional and Biological Properties of Peptides Obtained by Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Whey Proteins1. J. Dairy Sci. 2003, 86, E78–E87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis, 16th ed.; Association of Official Analytical Communities: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Noptana, R.; Onsaard, E. Enhanced Physical Stability of Rice Bran Oil-in-Water Emulsion by Heat and Alkaline Treated Proteins from Rice Bran and Soybean. Sci. Technol. Asia 2018, 23, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, M.; Hettiarachchy, N.S.; Kalapathy, U. Solubility and emulsifying properties of soy protein isolates modified by pancreatin. J. Food Sci. 1997, 62, 1110–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowry, O.H.; Rosebrough, N.J.; Farr, A.L.; Randall, R.J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 1951, 193, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laemmli, U.K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 1970, 227, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castel, V.; Andrich, O.; Netto, F.M.; Santiago, L.G.; Carrara, C.R. Total phenolic content and antioxidant activity of different streams resulting from pilot-plant processes to obtain Amaranthus mantegazzianus protein concentrates. J. Food Eng. 2014, 122, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.-Y.; Lai, H.-M. Bioactive compounds in rice during grain development. Food Chem. 2011, 127, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuyal, N.; Jha, P.K.; Raturi, P.P.; Rajbhandary, S. Total Phenolic, Flavonoid Contents, and Antioxidant Activities of Fruit, Seed, and Bark Extracts of Zanthoxylum armatum DC. Sci. World J. 2020, 2020, 8780704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thamnarathip, P.; Jangchud, K.; Nitisinprasert, S.; Vardhanabhuti, B. Identification of peptide molecular weight from rice bran protein hydrolysate with high antioxidant activity. J. Cereal Sci. 2016, 69, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girgih, A.T.; He, R.; Malomo, S.; Offengenden, M.; Wu, J.; Aluko, R.E. Structural and functional characterization of hemp seed (Cannabis sativa L.) protein-derived antioxidant and antihypertensive peptides. J. Funct. Foods 2014, 6, 384–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Zhang, L.; Sun, Q.; Song, G.; Huang, J. Extraction, identification and structure-activity relationship of antioxidant peptides from sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) protein hydrolysate. Food Res. Int. 2019, 116, 707–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phongthai, S.; Lim, S.-T.; Rawdkuen, S. Optimization of microwave-assisted extraction of rice bran protein and its hydrolysates properties. J. Cereal Sci. 2016, 70, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Castro, R.J.S.; Sato, H.H. Biologically active peptides: Processes for their generation, purification and identification and ap-plications as natural additives in the food and pharmaceutical industries. Food Res. Int. 2015, 74, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, P.P.; Gul, M.Z.; Weber, A.M.; Srivastava, R.K.; Marathi, B.; Ryan, E.P.; Ghazi, I.A. Rice Bran Extraction and Stabilization Methods for Nutrient and Phytochemical Biofortification, Nutraceutical Development, and Dietary Supplementation. Nutr. Rev. 2025, 83, 692–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aondona, M.M.; Ikya, J.K.; Ukeyima, M.T.; Gborigo, T.J.A.; Aluko, R.E.; Girgih, A.T. In vitro antioxidant and antihypertensive properties of sesame seed enzymatic protein hydrolysate and ultrafiltration peptide fractions. J. Food Biochem. 2021, 45, e13587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segla Koffi Dossou, S.; Xu, F.; You, J.; Zhou, R.; Li, D.; Wang, L. Widely targeted metabolome profiling of different colored sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) seeds provides new insight into their antioxidant activities. Food Res. Int. 2022, 151, 110850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsa, S.; Puechkamutr, Y. Pyrazine yield and functional properties of rice bran protein hydrolysate formed by the Maillard reaction at varying pH. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 59, 890–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shay, N.; Jing, X.; Bhandari, B.; Dayananda, B.; Prakash, S. Effect of enzymatic hydrolysis on solubility and surface properties of pea, rice, hemp, and oat proteins: Implication on high protein concentrations. Food Biosci. 2023, 53, 102515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, X.; Yue, C.; Wang, Y.; Shao, M.; Yu, G. Effect of limited enzymatic hydrolysis on the structure and emulsifying properties of rice bran protein. J. Cereal Sci. 2019, 85, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundi, S.; Aluko, R. Inhibitory properties of kidney bean protein hydrolysate and its membrane fractions against renin, an-giotensin converting enzyme, and free radicals. Austin J. Nutr. Food Sci. 2014, 2, 1008–1019. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.U.; Hettiarachchy, N.S.; Qi, M. Hydrophobicity, solubility, and emulsifying properties of soy protein peptides prepared by papain modification and ultrafiltration. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1998, 75, 845–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaprasob, R.; Khongdetch, J.; Laohakunjit, N.; Selamassakul, O.; Kaisangsri, N. Isolation and characterization, antioxidant, and antihypertensive activity of novel bioactive peptides derived from hydrolysis of King Boletus mushroom. LWT 2022, 160, 113287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaprakash, G.; Bains, A.; Chawla, P.; Fogarasi, M.; Fogarasi, S. A Narrative Review on Rice Proteins: Current Scenario and Food Industrial Application. Polymers 2022, 14, 3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, N.; Wang, J.-M.; Gong, Q.; Yang, X.-Q.; Yin, S.-W.; Qi, J.-R. Characterization and In Vitro digestibility of rice protein prepared by enzyme-assisted microfluidization: Comparison to alkaline extraction. J. Cereal Sci. 2012, 56, 482–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Xu, S.; Liu, H.-M.; Liu, M.-W.; Wang, C.-X.; Qin, Z.; Wang, X.-D. Effects of roasting temperature and duration on color and flavor of a sesame oligosaccharide-protein complex in a Maillard reaction model. Food Chem. X 2022, 16, 100483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Bernardini, R.; Mullen, A.M.; Bolton, D.; Kerry, J.; O’Neill, E.; Hayes, M. Assessment of the angiotensin-I-converting enzyme (ACE-I) inhibitory and antioxidant activities of hydrolysates of bovine brisket sarcoplasmic proteins produced by papain and characterisation of associated bioactive peptidic fractions. Meat Sci. 2012, 90, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phongthai, S.; Rawdkuen, S.J.F.; Journal, A.B. Preparation of rice bran protein isolates using three-phase partitioning and its properties. Food Appl. Biosci. J. 2015, 3, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Liang, R.; Yang, Y.; Sun, N.; Lin, S. Optimization of pea protein hydrolysate preparation and purification of antioxidant peptides based on an in silico analytical approach. LWT 2020, 123, 109126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olagunju, A.I.; Omoba, O.S.; Enujiugha, V.N.; Alashi, A.M.; Aluko, R.E. Pigeon pea enzymatic protein hydrolysates and ultra-filtration peptide fractions as potential sources of antioxidant peptides: An in vitro study. LWT 2018, 97, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memarpoor-Yazdi, M.; Mahaki, H.; Zare-Zardini, H. Antioxidant activity of protein hydrolysates and purified peptides from Zizyphus jujuba fruits. J. Funct. Foods 2013, 5, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foh, M.; Qixing, J.; Amadou, I.; Xia, W.S. Influence of Ultrafiltration on Antioxidant Activity of Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) Protein Hydrolysate. Adv. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 2, 227–235. [Google Scholar]

| Samples | L* | a* | b* | ΔE* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBP | 54.14 ± 0.69 G | 4.40 ± 0.59 A | 13.03 ± 0.18 F | - |

| RBPH-B | 69.12 ± 0.33 bF | 2.61 ± 0.16 aB | 15.20 ± 0.58 dE | 15.25 ± 0.33 dG |

| RBPH-B-F1 | 70.23 ± 1.85 bEF | 2.56 ± 0.20 aB | 16.69 ± 0.01 cD | 16.61 ± 1.80 cdF |

| RBPH-B-F2 | 70.78 ± 0.44 bE | 2.53 ± 0.19 aB | 17.52 ± 0.30 cC | 17.34 ± 0.36 cF |

| RBPH-B-F3 | 73.58 ± 0.42 aD | 2.01 ± 0.19 bC | 18.39 ± 0.54 bB | 20.31 ± 0.52 bE |

| RBPH-B-F4 | 75.04 ± 0.42 aC | 1.65 ± 0.32 bC | 19.61 ± 0.65 aA | 22.09 ± 0.25 aC |

| RBPH-C | 75.33 ± 0.80 cC | 0.16 ± 0.05 aD | 13.11 ± 0.18 cF | 21.61 ± 0.78 cCD |

| RBPH-C-F1 | 74.39 ± 0.02 dCD | 0.16 ± 0.05 aD | 13.14 ± 0.15 cF | 20.69 ± 0.02 dDE |

| RBPH-C-F2 | 75.36 ± 0.02 cC | 0.20 ± 0.01 aD | 13.36 ± 0.08 bF | 21.63 ± 0.02 cCD |

| RBPH-C-F3 | 81.29 ± 0.07 bB | −0.60 ± 0.16 cE | 14.95 ± 0.04 aE | 27.67 ± 0.10 bB |

| RBPH-C-F4 | 82.97 ± 0.00 aA | −0.33 ± 0.03 bE | 14.99 ± 0.01 aE | 29.28 ± 0.00 aA |

| Samples | EC50 | Metal Chelating Activity (mmol EDTA/g Sample) | Inhibition of Linoleic Acid Peroxidation (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABTS+ (mg/mL) | DPPH (µg/mL) | |||

| Ascorbic acid | 0.19 ± 0.00 I | 2.42 ± 0.15 G | 0.04 ± 0.00 G | 18.99 ± 1.21 J |

| RBPH-B | 3.01 ± 0.13 aA | 908.60 ± 20.58 aA | 0.77 ± 0.02 cF | 35.99 ± 1.71 dI |

| RBPH-B-F1 | 2.58 ± 0.11 bB | 475.97 ± 28.20 bB | 0.79 ± 0.01 cEF | 47.84 ± 0.17 cG |

| RBPH-B-F2 | 2.30 ± 0.05 cC | 210.50 ± 10.38 cF | 0.84 ± 0.01 bDE | 49.85 ± 1.02 cF |

| RBPH-B-F3 | 1.99 ± 0.04 dD | 199.96 ± 6.43 cF | 0.89 ± 0.02 aC | 54.22 ± 0.84 bE |

| RBPH-B-F4 | 1.84 ± 0.01 dE | 202.44 ± 9.07 cF | 0.92 ± 0.04 aC | 77.08 ± 1.61 aB |

| RBPH-C | 1.99 ± 0.03 aD | 399.80 ± 4.67 aC | 0.88 ± 0.02 cCD | 46.57 ± 0.13 dG |

| RBPH-C-F1 | 1.98 ± 0.02 aD | 329.50 ± 7.67 bD | 0.93 ± 0.07 cC | 42.50 ± 0.49 eH |

| RBPH-C-F2 | 1.60 ± 0.05 bF | 300.80 ± 7.10 cE | 1.02 ± 0.02 bB | 57.57 ± 1.41 cD |

| RBPH-C-F3 | 1.37 ± 0.03 cG | 280.83 ± 4.04 dE | 1.06 ± 0.01 bB | 70.60 ± 0.55 bC |

| RBPH-C-F4 | 0.94 ± 0.04 dH | 210.53 ± 2.02 eF | 1.35 ± 0.05 aA | 90.62 ± 0.15 aA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Noptana, R.; McClements, D.J.; McLandsborough, L.A.; Onsaard, W.; Onsaard, E. Rice Bran-Derived Peptides with Antioxidant Activity: Effects of Enzymatic Hydrolysis Using Bacillus licheniformis and α-Chymotrypsin. Foods 2026, 15, 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030516

Noptana R, McClements DJ, McLandsborough LA, Onsaard W, Onsaard E. Rice Bran-Derived Peptides with Antioxidant Activity: Effects of Enzymatic Hydrolysis Using Bacillus licheniformis and α-Chymotrypsin. Foods. 2026; 15(3):516. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030516

Chicago/Turabian StyleNoptana, Rodjana, David Julian McClements, Lynne A. McLandsborough, Wiriya Onsaard, and Ekasit Onsaard. 2026. "Rice Bran-Derived Peptides with Antioxidant Activity: Effects of Enzymatic Hydrolysis Using Bacillus licheniformis and α-Chymotrypsin" Foods 15, no. 3: 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030516

APA StyleNoptana, R., McClements, D. J., McLandsborough, L. A., Onsaard, W., & Onsaard, E. (2026). Rice Bran-Derived Peptides with Antioxidant Activity: Effects of Enzymatic Hydrolysis Using Bacillus licheniformis and α-Chymotrypsin. Foods, 15(3), 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15030516