Ecological and Human Health Risk Assessment of Metals in Peruvian Avocados Using a Probabilistic Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

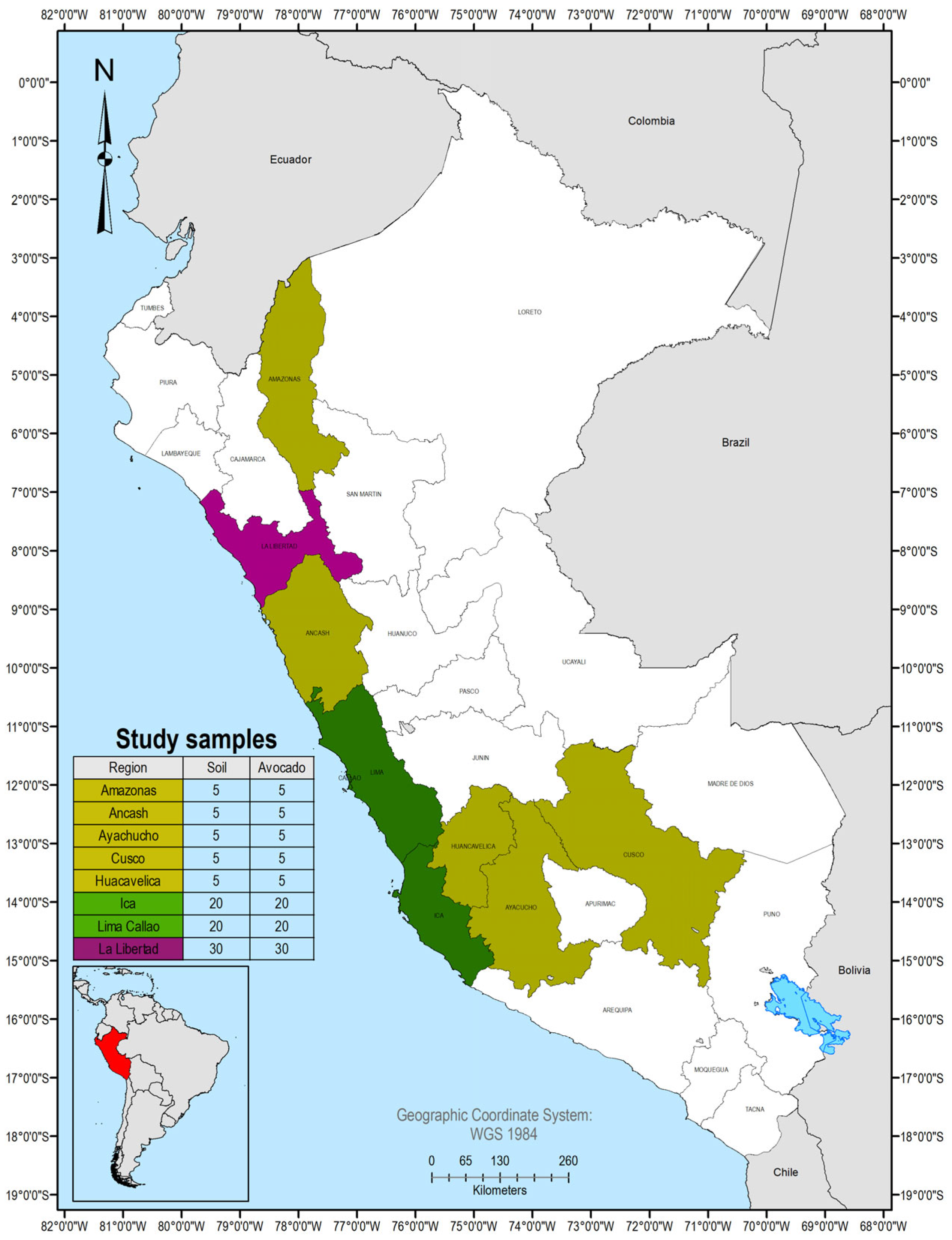

2.1. Sample Collection and Pre-Treatment

2.2. Chemical Analysis

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Concentration of Metals

3.1.1. Concentration of Metals in Soil

3.1.2. Concentration of Metals in Avocado

3.2. Ecological Risk of Metals

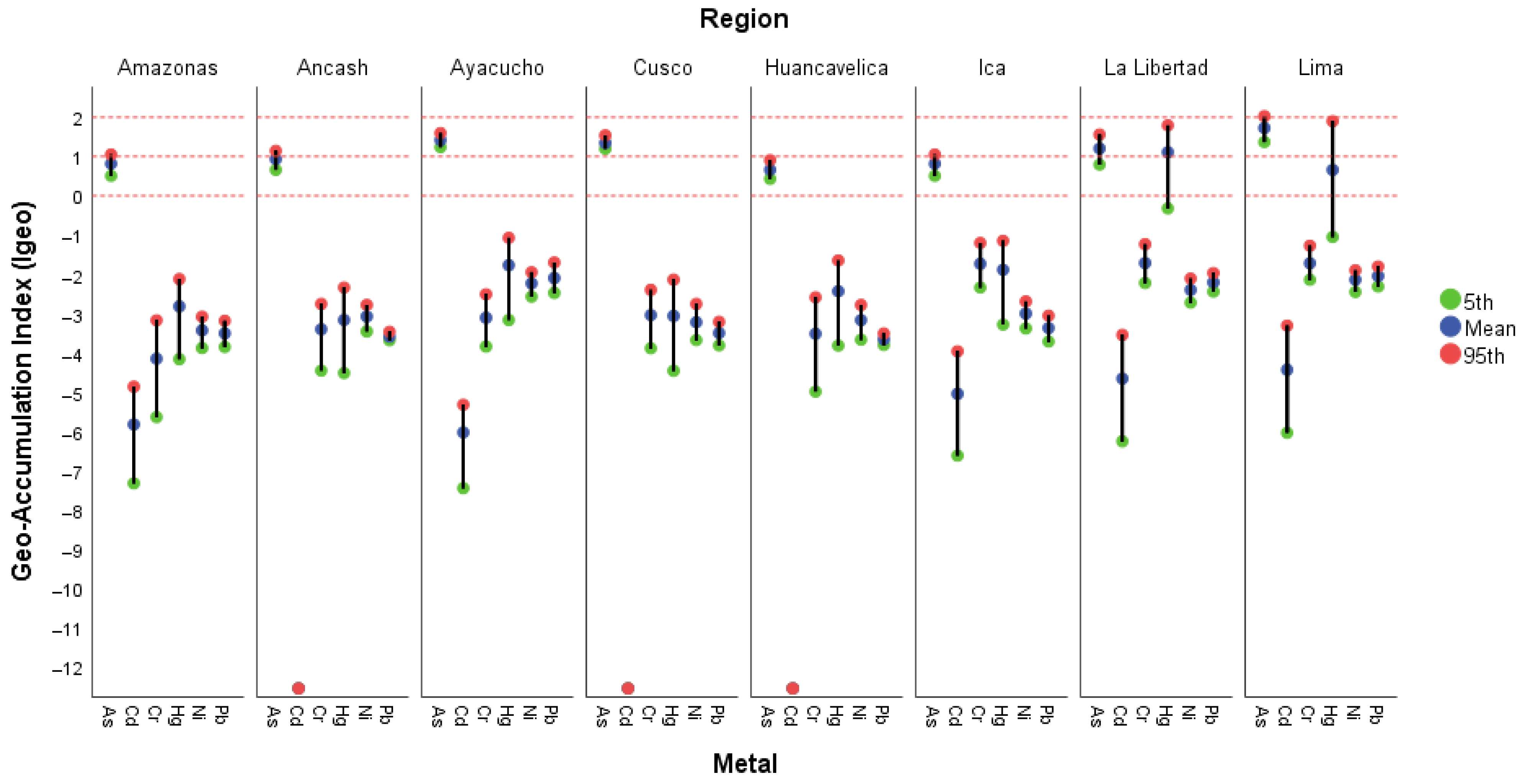

3.2.1. Geo-Accumulation Index

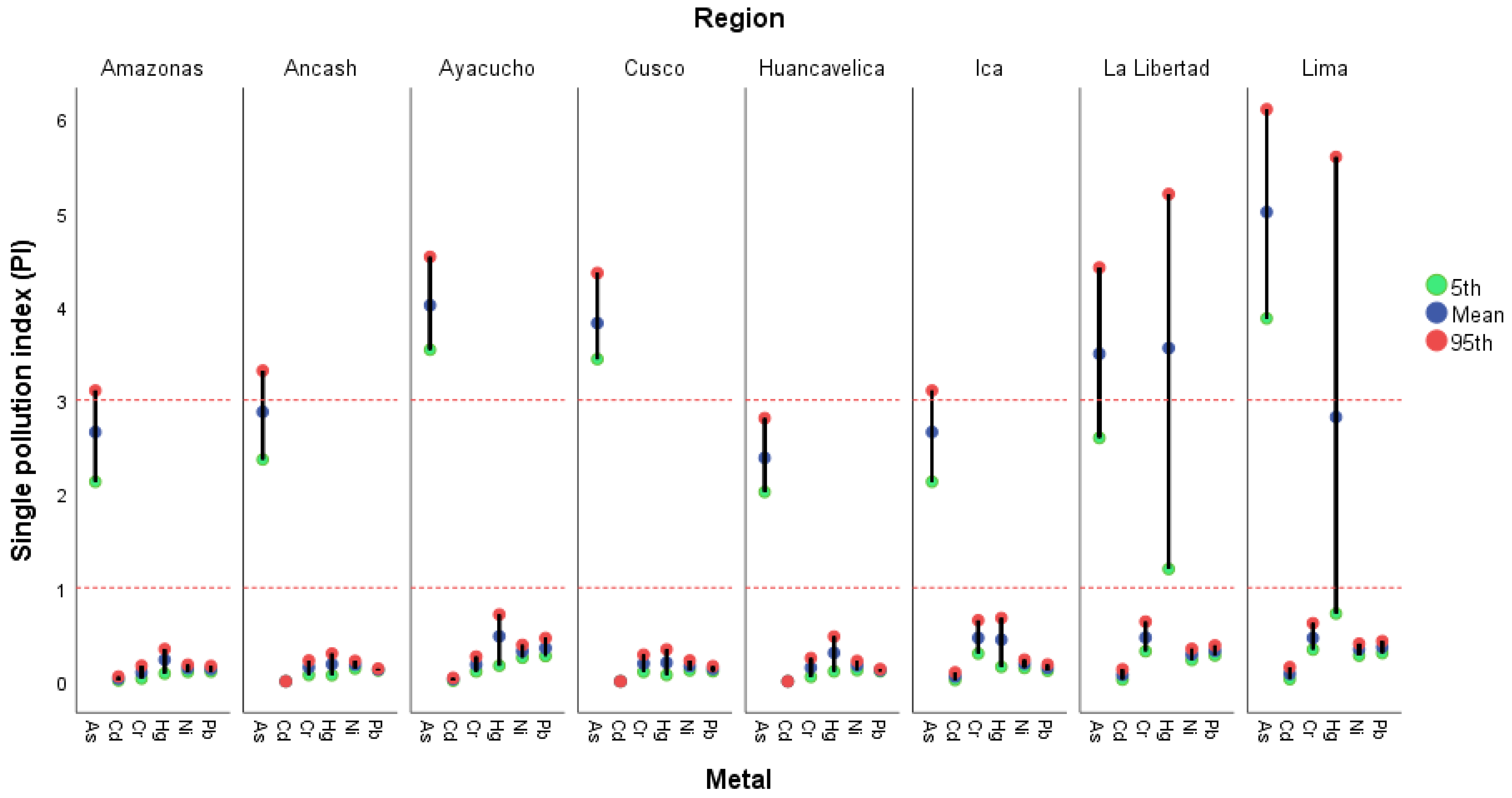

3.2.2. Single Pollution Index

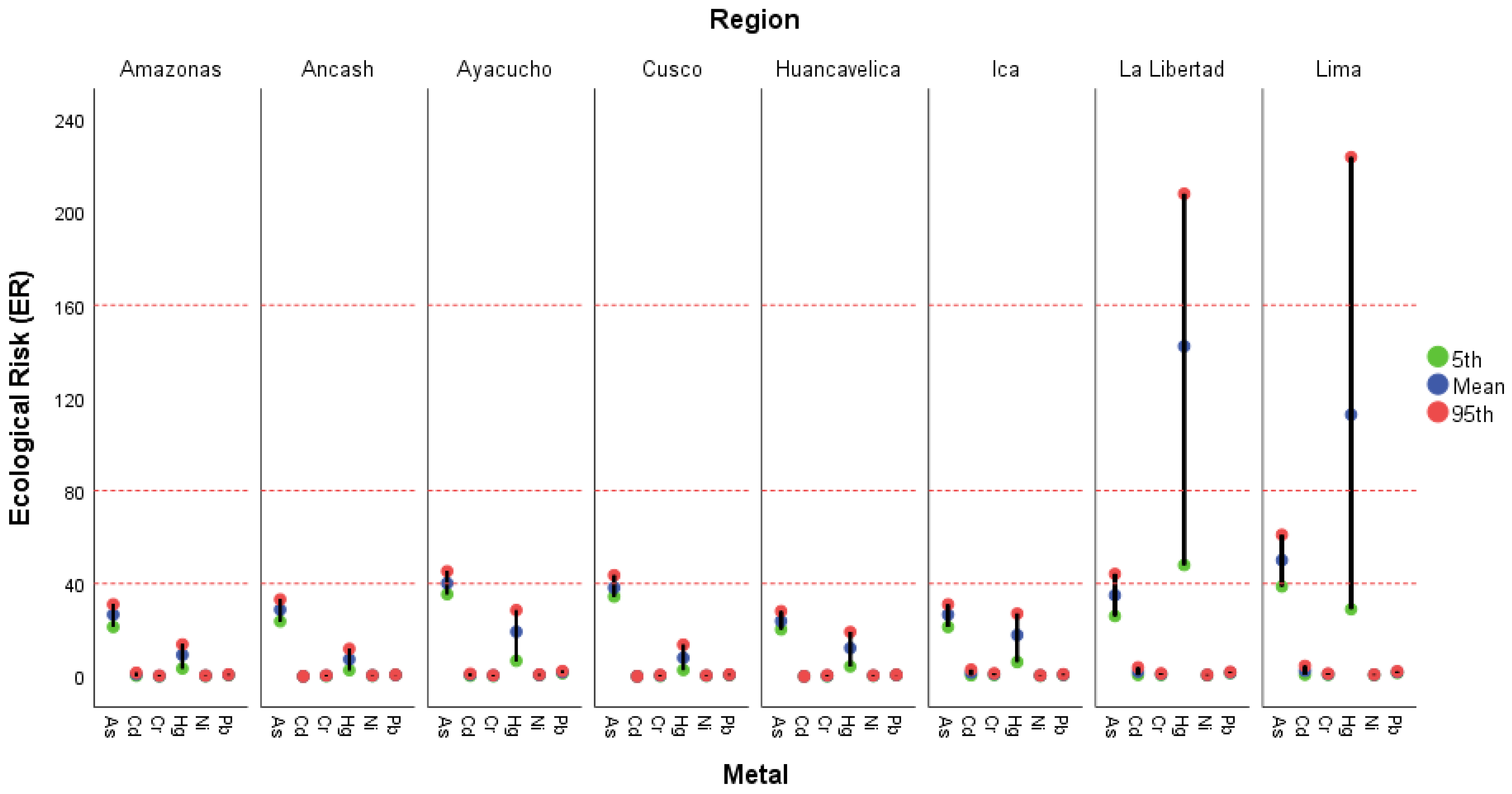

3.2.3. Ecological Risk

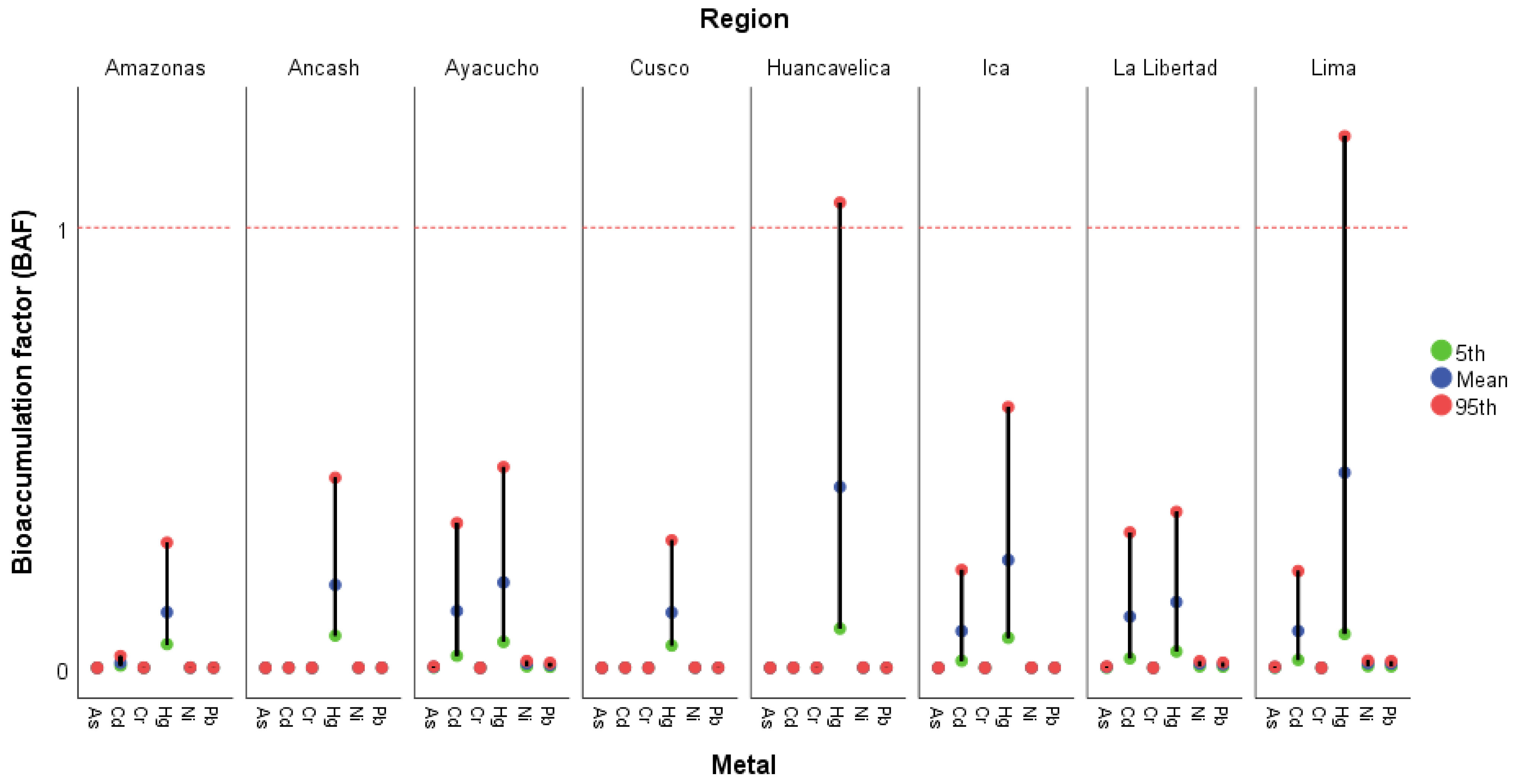

3.3. Bioaccumulation of Metals

3.4. Health Risk Assessment

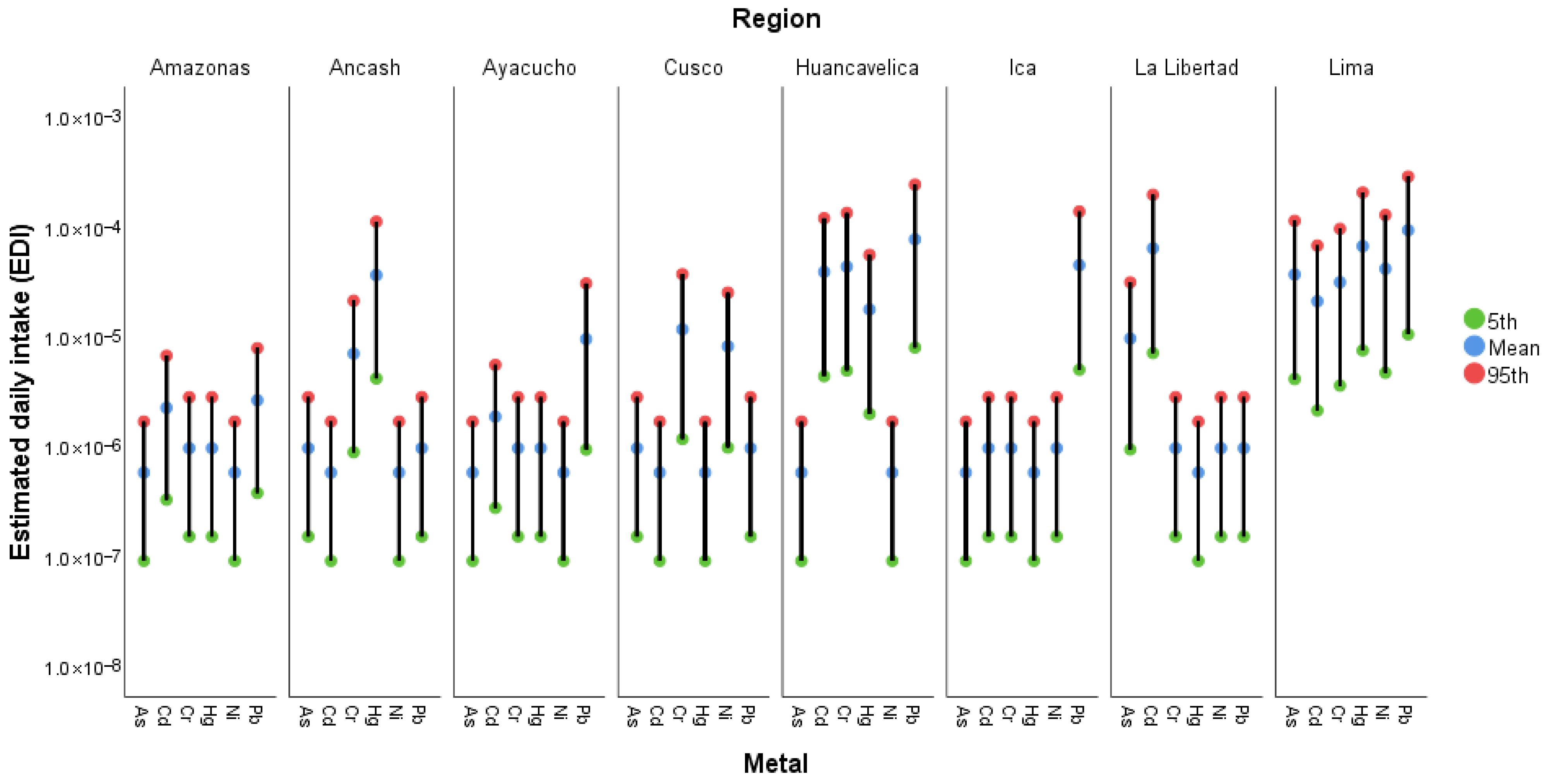

3.4.1. Estimated Daily Intake

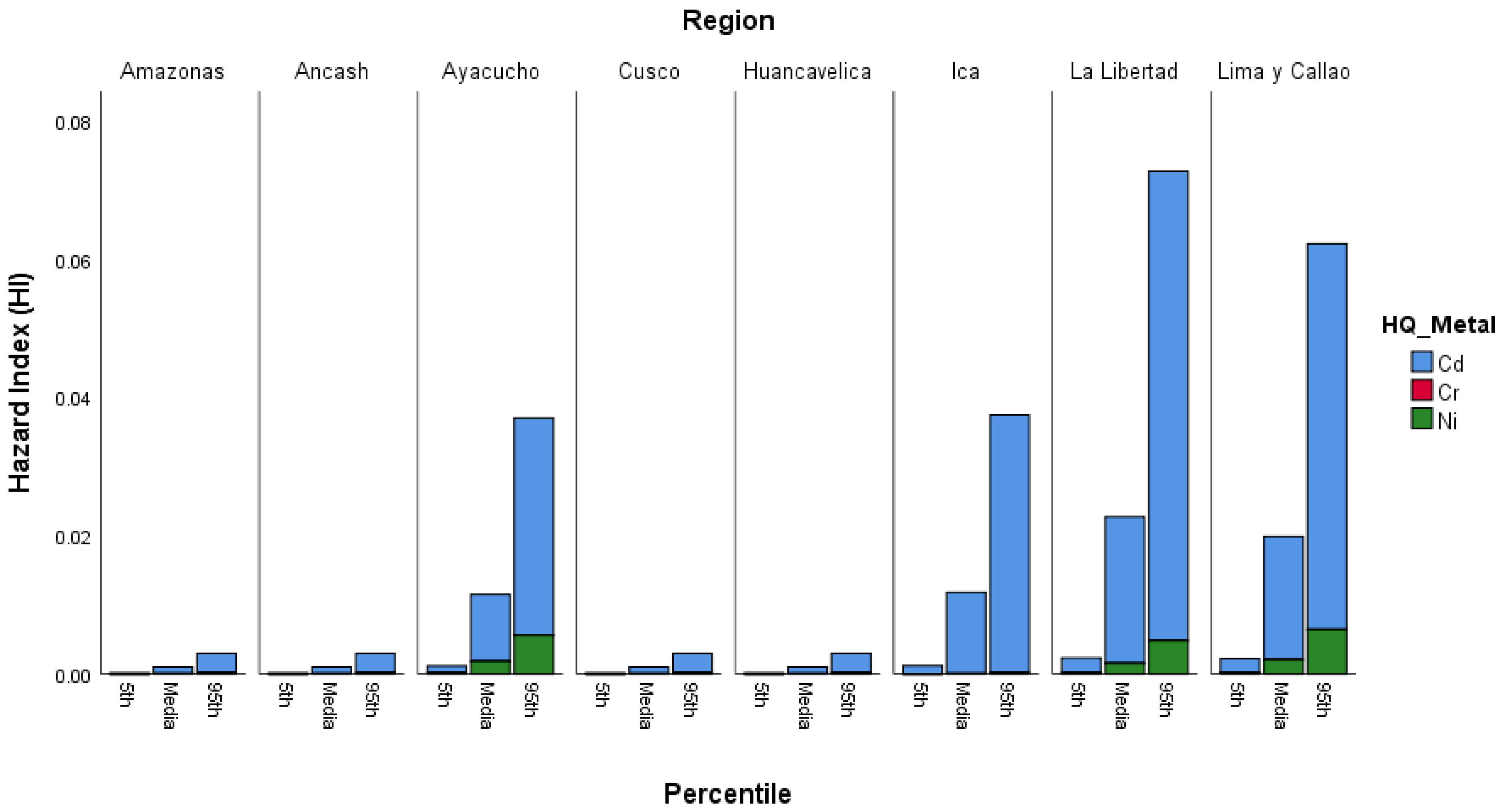

3.4.2. Hazard Index

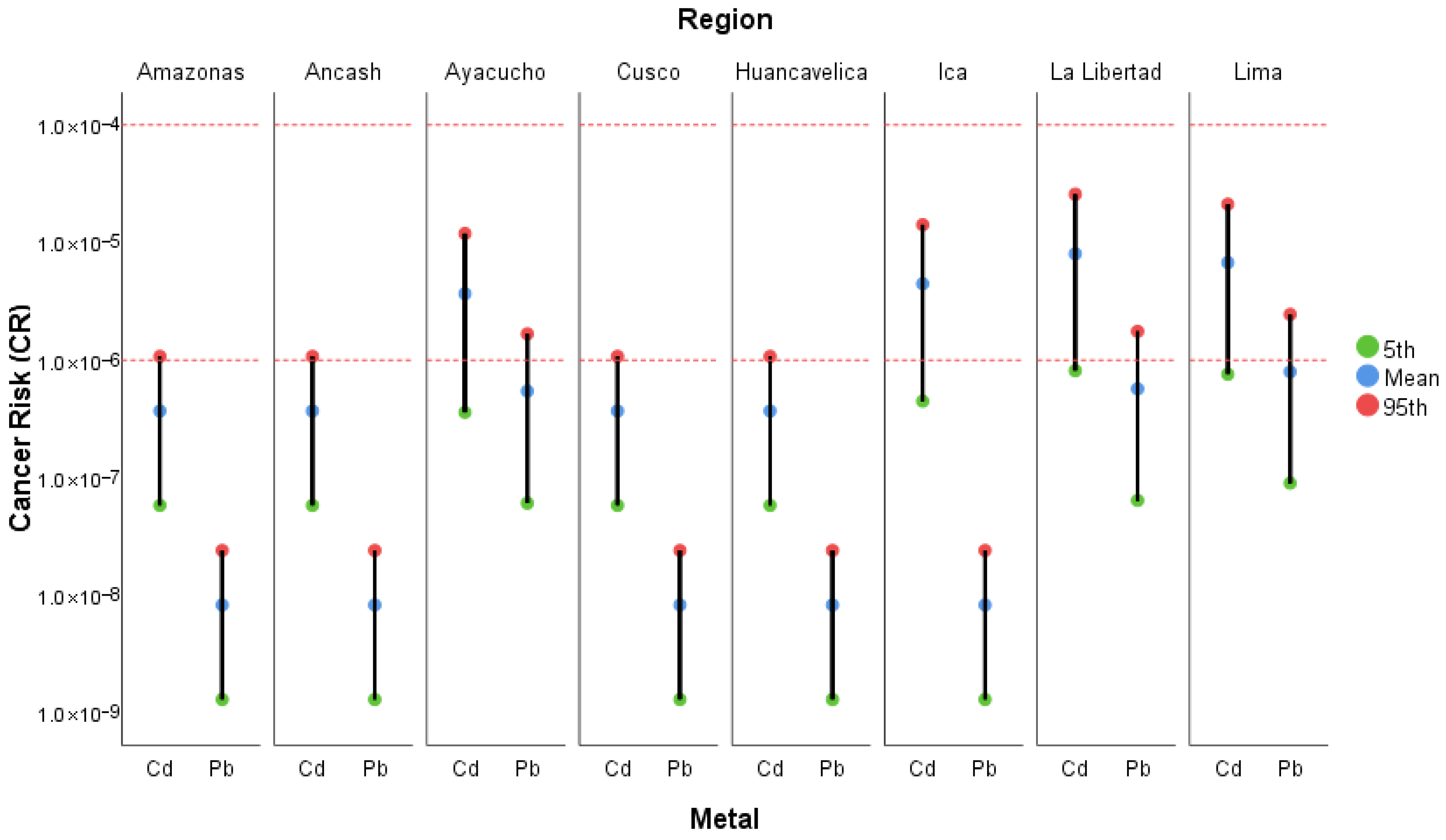

3.4.3. Cancer Risk

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Solares, E.; Morales-Cruz, A.; Balderas, R.F.; Focht, E.; Ashworth, V.E.T.M.; Wyant, S.; Minio, A.; Cantu, D.; Arpaia, M.L.; Gaut, B.S. Insights into the Domestication of Avocado and Potential Genetic Contributors to Heterodichogamy. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2023, 13, jkac323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, D.Y.; Cho, J.S.; Lim, J.H.; Choi, J.H.; Park, K.J. Investigation of Metabolomic Characteristics of ‘Hass’ Avocados (Persea americana Mill. Hass) during Postharvest Ripening Using NMR-Based Untargeted Metabolomics. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2026, 231, 113915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbano Marinho, J.F.; Souza Andrada Anconi, A.C.; de Souza, N.O.; do Bem, M.M.; Nunes, C.A. Technological Insights into Avocado Oil: From Nutritional Composition to Innovation in Food Applications. Food Biosci. 2025, 74, 107827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, A.P.S.; Duarte, M.E.M.; Rocha, A.P.T.; Barros, A.N. Bioactive Compounds, Technological Advances, and Sustainable Applications of Avocado (Persea americana Mill.): A Critical Review. Foods 2025, 14, 2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmassani, H.A.; Avendano, E.E.; Raman, G.; Johnson, E.J. Avocado Consumption and Risk Factors for Heart Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 107, 523–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacheco, L.S.; Li, Y.; Rimm, E.B.; Manson, J.A.E.; Sun, Q.; Rexrode, K.; Hu, F.B.; Guasch-Ferré, M. Avocado Consumption and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease in US Adults. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, e024014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Gonzáles, N.E.; García-Frutos, R.; Martínez-Chávez, L.; Domínguez-Bustos, F.O.; Díaz-Patiño, C.J.; Gutiérrez-González, P. Postharvest Reduction of Salmonella on Hass Avocado Epicarp by Hot Water Immersion and Evaluation of Fruit Quality. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2026, 444, 111444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, P.; Garcia, P.; Quitral, V.; Vasquez, K.; Parra-Ruiz, C.; Reyes-Farias, M.; Garcia-Diaz, D.F.; Robert, P.; Encina, C.; Soto-Covasich, J. Pulp, Leaf, Peel and Seed of Avocado Fruit: A Review of Bioactive Compounds and Healthy Benefits. Food Rev. Int. 2021, 37, 619–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collantes-Barturen, F.J.A.; Morán-Santamaría, R.O. Impact of Avocado Exports on Peruvian Economic Growth. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solórzano Acosta, R.A.; Llerena, R.; Mejía, S.; Cruz-Luis, J.A.; Quispe, K.R. Spatial Distribution of Cadmium in Avocado-Cultivated Soils of Peru: Influence of Parent Material, Exchangeable Cations, and Trace Elements. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guadalupe, G.A.; García, L.M.; Chavez, S.G.; Doménech, E. Ecological and Health Risk Assessment of Metals in Organic and Conventional Peruvian Coffee from a Probabilistic Approach. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciuttolo, C.; Cano, D.; Custodio, M. Socio-Environmental Risks Linked with Mine Tailings Chemical Composition: Promoting Responsible and Safe Mine Tailings Management Considering Copper and Gold Mining Experiences from Chile and Peru. Toxics 2023, 11, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custodio, M.; Fow, A.; Chanamé, F.; Orellana-Mendoza, E.; Peñaloza, R.; Alvarado, J.C.; Cano, D.; Pizarro, S. Ecological Risk Due to Heavy Metal Contamination in Sediment and Water of Natural Wetlands with Tourist Influence in the Central Region of Peru. Water 2021, 13, 2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah Alnuwaiser, M. An Analytical Survey of Trace Heavy Elements in Insecticides. Int. J. Anal. Chem. 2019, 2019, 8150793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Defarge, N.; Spiroux de Vendômois, J.; Séralini, G.E. Toxicity of Formulants and Heavy Metals in Glyphosate-Based Herbicides and Other Pesticides. Toxicol. Rep. 2018, 5, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K.A.; Tzilivakis, J.; Warner, D.J.; Green, A. An International Database for Pesticide Risk Assessments and Management. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. 2016, 22, 1050–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wei, D.; Zhu, Y.G. An Inventory of Trace Element Inputs to Agricultural Soils in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 2524–2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyanka, P.; Kumar, D.; Yadav, A.; Yadav, K. Nanobiotechnology and Its Application in Agriculture and Food Production; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, A.; Schutte, B.J.; Ulery, A.; Deyholos, M.K.; Sanogo, S.; Lehnhoff, E.A.; Beck, L. Heavy Metal Contamination in Agricultural Soil: Environmental Pollutants Affecting Crop Health. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Z.; Mu, H.-Y.; Fu, P.-N.; Wan, Y.-N.; Yu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Li, H.-F. Accumulation of Potentially Toxic Elements in Agricultural Soil and Scenario Analysis of Cadmium Inputs by Fertilization: A Case Study in Quzhou County. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 269, 110797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soni, S.; Jha, A.B.; Dubey, R.S.; Sharma, P. Mitigating Cadmium Accumulation and Toxicity in Plants: The Promising Role of Nanoparticles. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 168826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismael, M.A.; Elyamine, A.M.; Moussa, M.G.; Cai, M.; Zhao, X.; Hu, C. Cadmium in Plants: Uptake, Toxicity, and Its Interactions with Selenium Fertilizers. Metallomics 2019, 11, 255–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guadalupe, G.A.; Chavez, S.G.; Arellanos, E.; Doménech, E. Probabilistic Risk Characterization of Heavy Metals in Peruvian Coffee: Implications of Variety, Region and Processing. Foods 2023, 12, 3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angon, P.B.; Islam, M.S.; KC, S.; Das, A.; Anjum, N.; Poudel, A.; Suchi, S.A. Sources, Effects and Present Perspectives of Heavy Metals Contamination: Soil, Plants and Human Food Chain. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guadalupe, G.A.; Grandez-Yoplac, D.E.; García, L.; Doménech, E. A Comprehensive Bibliometric Study in the Context of Chemical Hazards in Coffee. Toxics 2024, 12, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitra, S.; Chakraborty, A.J.; Tareq, A.M.; Bin Emran, T.; Nainu, F.; Khusro, A.; Idris, A.M.; Khandaker, M.U.; Osman, H.; Alhumaydhi, F.A.; et al. Impact of Heavy Metals on the Environment and Human Health: Novel Therapeutic Insights to Counter the Toxicity. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2022, 34, 101865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Yuan, X.; Li, T.; Hu, S.; Ji, J.; Wang, C. Characteristics of Heavy Metal Transfer and Their Influencing Factors in Different Soil–Crop Systems of the Industrialization Region, China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf 2016, 126, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q.; Yu, T.; Yang, Z.; Ji, J.; Hou, Q.; Wang, L.; Wei, X.; Zhang, Q. Prediction and Risk Assessment of Five Heavy Metals in Maize and Peanut: A Case Study of Guangxi, China. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2019, 70, 103199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, S.; Ahmad, K. Heavy Metal Contamination in Water and Fish of the Hunza River and Its Tributaries in Gilgit–Baltistan: Evaluation of Potential Risks and Provenance. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2020, 20, 101159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, U.K.; Kumar, B. Pathways of Heavy Metals Contamination and Associated Human Health Risk in Ajay River Basin, India. Chemosphere 2017, 174, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tezotto, T.; Favarin, J.L.; Azevedo, R.A.; Alleoni, L.R.F.; Mazzafera, P. Coffee Is Highly Tolerant to Cadmium, Nickel and Zinc: Plant and Soil Nutritional Status, Metal Distribution and Bean Yield. Field Crops Res. 2012, 125, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Yadav, K.K.; Kumar, V.; Kumar, S.; Chadd, R.P.; Kumar, A. Trace Elements in Soil-Vegetables Interface: Translocation, Bioaccumulation, Toxicity and Amelioration—A Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 651, 2927–2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Naranjo, A.; Mayorga-Naranjo, C.; Vélez-Terreros, P.Y.; Yánez-Jácome, G.S.; Oviedo-Chávez, A.C.; Navarrete Zambrano, H.; Vinueza-Galáraga, J.; Romero-Estévez, D. Fixed-Bed Columns of Avocado (Persea americana Hass.) Seed and Peel Biomass as a Retainer for Contaminating Metals. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.I.; Ugulu, I.; Sahira, S.; Ahmad, K.; Ashfaq, A.; Mehmood, N.; Dogan, Y. Determination of Toxic Metals in Fruits of Abelmoschus Esculentus Grown in Contaminated Soils with Different Irrigation Sources by Spectroscopic Method. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2018, 12, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, G.A.; Alves Martins, M.V.; Santos, L.M.G.; Neto, S.A.V.; Junior, F.B.; Geraldes, M.C.; Bergamaschi, S.B.; Figueira, R.C.L.; Patinha, C.A.F.; da Silva, E.F. Contamination by Potentially Toxic Elements (PTEs) in Agricultural Products Grown Around Sepetiba Bay, Rio de Janeiro State (SE Brazil). Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2025, 89, 195–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuong Nguyen, X.; Thanh Huyen Nguyen, T.; Hong Chuong Nguyen, T.; Van Le, Q.; Yen Binh Vo, T.; Cuc Phuong Tran, T.; Duong La, D.; Kumar, G.; Khanh Nguyen, V.; Chang, S.W.; et al. Sustainable Carbonaceous Biochar Adsorbents Derived from Agro-Wastes and Invasive Plants for Cation Dye Adsorption from Water. Chemosphere 2021, 282, 131009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midhat, L.; Ouazzani, N.; Hejjaj, A.; Ouhammou, A.; Mandi, L. Accumulation of Heavy Metals in Metallophytes from Three Mining Sites (Southern Centre Morocco) and Evaluation of Their Phytoremediation Potential. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 169, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.D.; Kim, M.S. Cadmium, Lead, and Mercury Mixtures Interact with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Diseases. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 309, 119780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skalny, A.V.; Aschner, M.; Sekacheva, M.I.; Santamaria, A.; Barbosa, F.; Ferrer, B.; Aaseth, J.; Paoliello, M.M.B.; Rocha, J.B.T.; Tinkov, A.A. Mercury and Cancer: Where Are We Now after Two Decades of Research? Food Chem. Toxicol. 2022, 164, 113001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Steven Xu, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Tao, F.; Yuan, M. Stratification of Population in NHANES 2009–2014 Based on Exposure Pattern of Lead, Cadmium, Mercury, and Arsenic and Their Association with Cardiovascular, Renal and Respiratory Outcomes. Environ. Int. 2021, 149, 106410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanarella, L.; Panagos, P. The Relevance of Sustainable Soil Management within the European Green Deal. Land Use Policy 2021, 100, 104950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO; UNEP; WHO; WOAH FAO; World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) (Founded as OIE). Available online: https://www.fao.org/one-health/resources/publications/joint-plan-of-action (accessed on 14 October 2022).

- Orellana Mendoza, E.; Cuadrado, W.; Yallico, L.; Zárate, R.; Quispe-Melgar, H.R.; Limaymanta, C.H.; Sarapura, V.; Bao-Cóndor, D. Heavy Metals in Soils and Edible Tissues of Lepidium Meyenii (Maca) and Health Risk Assessment in Areas Influenced by Mining Activity in the Central Region of Peru. Toxicol. Rep. 2021, 8, 1461–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, E.O.; Custodio, M.; Ascensión, J.; Bastos, M.C. Heavy Metals in Soils from High Andean Zones and Potential Ecological Risk Assessment in Peru’s Central Andes. J. Ecol. Eng. 2020, 21, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arévalo-Gardini, E.; Arévalo-Hernández, C.O.; Baligar, V.C.; He, Z.L. Heavy Metal Accumulation in Leaves and Beans of Cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) in Major Cacao Growing Regions in Peru. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 605–606, 792–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.; Ramos, S.; Delerue-Matos, C.; Morais, S. Espresso Beverages of Pure Origin Coffee: Mineral Characterization, Contribution for Mineral Intake and Geographical Discrimination. Food Chem. 2015, 177, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y. Comprehensive Perspective on Contamination Identification, Source Apportionment, and Ecological Risk Assessment of Heavy Metals in Paddy Soils of a Tropical Island. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaro-Espejo, I.A.; Del Refugio Castañeda-Chávez, M.; Murguía-González, J.; Lango-Reynoso, F.; Patricia Bañuelos-Hernández, K.; Galindo-Tovar, M.E. Geoaccumulation and Ecological Risk Indexes in Papaya Cultivation Due to the Presence of Trace Metals. Agronomy 2020, 10, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Behairy, R.A.; El Baroudy, A.A.; Ibrahim, M.M.; Mohamed, E.S.; Rebouh, N.Y.; Shokr, M.S. Combination of GIS and Multivariate Analysis to Assess the Soil Heavy Metal Contamination in Some Arid Zones. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, J.K.; Noh, H.R.; Kang, T.; Kim, S.H. Distribution of Heavy Metals and Organic Compounds: Contamination and Associated Risk Assessment in the Han River Watershed, South Korea. Agronomy 2022, 12, 3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mickovski Stefanović, V.; Roljević Nikolić, S.; Matković Stojšin, M.; Majstorović, H.; Petreš, M.; Cvikić, D.; Racić, G. Soil-to-Wheat Transfer of Heavy Metals Depending on the Distance from the Industrial Zone. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Gao, Z.; Liu, J.; Jiang, B. Study on the Accumulation of Heavy Metals in Different Soil-Crop Systems and Ecological Risk Assessment: A Case Study of Jiao River Basin. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shen, W.; Fan, K.; Pei, W.; Liu, S. Spatial Distribution, Source Analysis, and Health Risk Assessment of Heavy Metals in the Farmland of Tangwang Village, Huainan City, China. Agronomy 2024, 14, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Hao, M.; Li, Y.; Li, S. Contamination, Sources and Health Risks of Toxic Elements in Soils of Karstic Urban Parks Based on Monte Carlo Simulation Combined with a Receptor Model. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 839, 156223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, S.L.C.; da Silva, J.B.; dos Santos, I.F.; de Oliveira, O.M.C.; Cerda, V.; Queiroz, A.F.S. Use of Pollution Indices and Ecological Risk in the Assessment of Contamination from Chemical Elements in Soils and Sediments—Practical Aspects. Trends Environ. Anal. Chem. 2022, 35, e00169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.R.; McLennan, S.M. The Geochemical Evolution of the Continental Crust. Rev. Geophys. 1995, 33, 241–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Choudhary, A.; Darbha, G.K. From Ground to Gut: Evaluating the Human Health Risk of Potentially Toxic Elements in Soil, Groundwater, and Their Uptake by Cocos Nucifera in Arsenic-Contaminated Environments. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 344, 123342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPA IRIS Assessments | IRIS | US EPA. Available online: https://iris.epa.gov/AtoZ/?list_type=alpha (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Agyeman, P.C.; John, K.; Kebonye, N.M.; Borůvka, L.; Vašát, R.; Drábek, O.; Němeček, K. Human Health Risk Exposure and Ecological Risk Assessment of Potentially Toxic Element Pollution in Agricultural Soils in the District of Frydek Mistek, Czech Republic: A Sample Location Approach. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2021, 33, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyeman, P.C.; JOHN, K.; Kebonye, N.M.; Ofori, S.; Borůvka, L.; Vašát, R.; Kočárek, M. Ecological Risk Source Distribution, Uncertainty Analysis, and Application of Geographically Weighted Regression Cokriging for Prediction of Potentially Toxic Elements in Agricultural Soils. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2022, 164, 729–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guadalupe, G.A.; García, L.; Quispe-Sánchez, L.; Doménech, E. The Fault Tree Analysis (FTA) to Support Management Decisions on Pesticide Control in the Reception of Peruvian Parchment Coffee. Food Control 2024, 166, 110729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guadalupe, G.A.; Grández-Yoplac, D.E.; Arellanos, E.; Doménech, E. Probabilistic Risk Assessment of Metals, Acrylamide and Ochratoxin A in Instant Coffee from Brazil, Colombia, Mexico and Peru. Foods 2024, 13, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, A.; Mansour, S.N.; Najafi, M.L.; Toolabi, A.; Abdolahnejad, A.; Faraji, M.; Miri, M. Probabilistic Risk Assessment of Soil Contamination Related to Agricultural and Industrial Activities. Environ. Res. 2022, 203, 111837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alidadi, H.; Tavakoly Sany, S.B.; Zarif Garaati Oftadeh, B.; Mohamad, T.; Shamszade, H.; Fakhari, M. Health Risk Assessments of Arsenic and Toxic Heavy Metal Exposure in Drinking Water in Northeast Iran. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2019, 24, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, W.; Alharthy, R.D.; Zubair, M.; Ahmed, M.; Hameed, A.; Rafique, S. Toxic and Heavy Metals Contamination Assessment in Soil and Water to Evaluate Human Health Risk. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 17006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proshad, R.; Islam, S.; Tusher, T.R.; Zhang, D.; Khadka, S.; Gao, J.; Kundu, S. Appraisal of Heavy Metal Toxicity in Surface Water with Human Health Risk by a Novel Approach: A Study on an Urban River in Vicinity to Industrial Areas of Bangladesh. Toxin Rev. 2021, 40, 803–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mmaduakor, E.C.; Umeh, C.T.; Morah, J.E.; Omokpariola, D.O.; Ekwuofu, A.A.; Onwuegbuokwu, S.S. Pollution Status, Health Risk Assessment of Potentially Toxic Elements in Soil and Their Uptake by Gongronema Latifolium in Peri-Urban of Ora-Eri, South-Eastern Nigeria. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedoya-Perales, N.S.; Maus, D.; Neimaier, A.; Escobedo-Pacheco, E.; Pumi, G. Assessment of the Variation of Heavy Metals and Pesticide Residues in Native and Modern Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) Cultivars Grown at Different Altitudes in a Typical Mining Region in Peru. Toxicol. Rep. 2023, 11, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosales-Huamani, J.; Breña-Ore, J.; Landauro-Abanto, A.; Ñiquin, J.A.; Centeno-Rojas, L.; Otiniano-Zavala, A.; Andrade-Choque, J.; Medina-Collana, J. Determination of Potentially Toxic Elements in Quinoa Crops Located in the Huacaybamba–Huanuco-Peru Area. Int. J. Membr. Sci. Technol. 2023, 10, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirinos-Peinado, D.; Castro-Bedriñana, J.; Barnes, E.P.G.; Ríos-Ríos, E.; García-Olarte, E.; Castro-Chirinos, G. Assessing the Health Risk and Trophic Transfer of Lead and Cadmium in Dairy Farming Systems in the Mantaro Catchment, Central Andes of Peru. Toxics 2024, 12, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chirinos-Peinado, D.; Castro-Bedriñana, J.; Ríos-Ríos, E.; Castro-Chirinos, G.; Quispe-Poma, Y. Lead, Cadmium, and Arsenic in Raw Milk Produced in the Vicinity of a Mini Mineral Concentrator in the Central Andes and Health Risk. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2024, 202, 2376–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huamaní-Yupanqui, H.A.; Huauya-Rojas, M.A.; Mansilla-Minaya, L.G.; Florida-Rofner, N.; Neira-Trujillo, G.M. Presence of Heavy Metals in Organic Cacao [Theobroma cacao L.) Crop | Presencia de Metales Pesados En Cultivo de Cacao [Theobroma cacao L.) Orgánico. Acta Agronómica 2012, 61, 339–344. [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza-Guillen, J.A.; Alderete-Malpartida, M.B.; Escobar-Mendoza, J.E.; Navarro-Abarca, U.F.; Silva-Castro, K.A.; Martinez-Mercado, P.L. Identifying Contamination of Heavy Metals in Soils of Peruvian Amazon Plain: Use of Multivariate Statistical Techniques. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2022, 194, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.R.; Zeng, D.; She, L.; Su, W.X.; He, D.C.; Wu, G.Y.; Ma, X.R.; Jiang, S.; Jiang, C.H.; Ying, G.G. Comparisons of Pollution Characteristics, Emission Situations, and Mass Loads for Heavy Metals in the Manures of Different Livestock and Poultry in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 734, 139023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orellana-Mendoza, E.; Camel, V.; Yallico, L.; Quispe-Coquil, V.; Cosme, R. Effect of Fertilization on the Accumulation and Health Risk for Heavy Metals in Native Andean Potatoes in the Highlands of Perú. Toxicol. Rep. 2024, 12, 594–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Dong, Y.; Yang, Y.; Toor, G.S.; Zhang, X. Changes in Heavy Metal Contents in Animal Feeds and Manures in an Intensive Animal Production Region of China. J. Environ. Sci. 2013, 25, 2435–2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.; Cao, X.; Zhou, Q.; Ma, L.Q. Accumulation of Pb, Cu, and Zn in Native Plants Growing on a Contaminated Florida Site. Sci. Total Environ. 2006, 368, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Li, H.; Xue, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Cheng, F. Accumulation Characteristics and Potential Risk of Heavy Metals in Soil-Vegetable System under Greenhouse Cultivation Condition in Northern China. Ecol. Eng. 2017, 102, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi Khaneghah, A.; Mahmudiono, T.; Javanmardi, F.; Tajdar-oranj, B.; Nematollahi, A.; Pirhadi, M.; Fakhri, Y. The Concentration of Potentially Toxic Elements (PTEs) in the Coffee Products: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 78152–78164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda, M.; Avila, B.S.; Gallego Ríos, S.E.; Peñuela, G.A. Levels of Heavy Metals in Tropical Fruits and Soils from Agricultural Crops in Antioquia, Colombia. A Probabilistic Assessment of Health Risk Associated with Their Consumption. Food Humanit. 2025, 4, 100503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafulul, S.G.; Joel, E.B.; Gushit, J. Health Risk Assessment of Potentially Toxic Elements (PTEs) Concentrations in Soil and Fruits of Selected Perennial Economic Trees Growing Naturally in the Vicinity of the Abandoned Mining Ponds in Kuba, Bokkos Local Government Area (LGA) Plateau State, Nigeria. Environ. Geochem. Health 2023, 45, 5893–5914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlJuhaimi, F.Y.; Kulluk, D.A.; Gökmen Yılmaz, F.; Ahmed, I.A.M.; Musa Özcan, M.M.; Albakry, Z. Quantitative Determination of Minerals and Toxic Elements Content in Tropical and Subtropical Fruits by Microwave-Assisted Digestion and ICP-OES. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2025, 203, 1676–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babuskin, S.; Yessuf, A.M.; Hameed, O. Bin Monitoring and Assessment of the Potential Health Risks Associated with the Toxic Heavy Metals Content in Selected Fruits Grown in Arba Minch Region of Ethiopia. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2020, 102, 4941–4952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orellana-Mendoza, E.; Acevedo, R.R.; Huamán, C.H.; Zamora, Y.M.; Bastos, M.C.; Loardo-Tovar, H. Ecological Risk Assessment for Heavy Metals in Agricultural Soils Surrounding Dumps, Huancayo Province, Peru. J. Ecol. Eng. 2022, 23, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Francés, F.; Martínez-Graña, A.; Rojo, P.A.; Sánchez, A.G. Geochemical Background and Baseline Values Determination and Spatial Distribution of Heavy Metal Pollution in Soils of the Andes Mountain Range (Cajamarca-Huancavelica, Peru). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cáceres Choque, L.F.; Ramos Ramos, O.E.; Valdez Castro, S.N.; Choque Aspiazu, R.R.; Choque Mamani, R.G.; Fernández Alcazar, S.G.; Sracek, O.; Bhattacharya, P. Fractionation of Heavy Metals and Assessment of Contamination of the Sediments of Lake Titicaca. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2013, 185, 9979–9994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huerta Alata, M.; Alvarez-Risco, A.; Suni Torres, L.; Moran, K.; Pilares, D.; Carling, G.; Paredes, B.; Del-Aguila-Arcentales, S.; Yáñez, J.A. Evaluation of Environmental Contamination by Toxic Elements in Agricultural Soils and Their Health Risks in the City of Arequipa, Peru. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custodio, M.; Espinoza, C.; Orellana, E.; Chanamé, F.; Fow, A.; Peñaloza, R. Assessment of Toxic Metal Contamination, Distribution and Risk in the Sediments from Lagoons Used for Fish Farming in the Central Region of Peru. Toxicol. Rep. 2022, 9, 1603–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Sharma, A.; Kaur, P.; Singh Sidhu, G.P.; Bali, A.S.; Bhardwaj, R.; Thukral, A.K.; Cerda, A. Pollution Assessment of Heavy Metals in Soils of India and Ecological Risk Assessment: A State-of-the-Art. Chemosphere 2019, 216, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, H.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Ren, D.; Zhang, S. Ecological and Health Risk Assessments of Heavy Metals and Their Accumulation in a Peanut-Soil System. Environ. Res. 2024, 252, 118946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buscaroli, A. An Overview of Indexes to Evaluate Terrestrial Plants for Phytoremediation Purposes (Review). Ecol. Indic. 2017, 82, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ur Rahman, S.; Qin, A.; Zain, M.; Mushtaq, Z.; Mehmood, F.; Riaz, L.; Naveed, S.; Ansari, M.J.; Saeed, M.; Ahmad, I.; et al. Pb Uptake, Accumulation, and Translocation in Plants: Plant Physiological, Biochemical, and Molecular Response: A Review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satarug, S.; Vesey, D.A.; Gobe, G.C. Current Health Risk Assessment Practice for Dietary Cadmium: Data from Different Countries. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2017, 106, 430–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasemi, M.; Shams, M.; Sajjadi, S.A.; Farhang, M.; Erfanpoor, S.; Yousefi, M.; Zarei, A.; Afsharnia, M. Cadmium in Groundwater Consumed in the Rural Areas of Gonabad and Bajestan, Iran: Occurrence and Health Risk Assessment. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2019, 192, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Xiao, J.; Wang, L.; Liang, T.; Guo, Q.; Guan, Y.; Rinklebe, J. Elucidating the Differentiation of Soil Heavy Metals under Different Land Uses with Geographically Weighted Regression and Self-Organizing Map. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 260, 114065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Liao, Q.; Chillrud, S.N.; Yang, Q.; Huang, L.; Bi, J.; Yan, B. Environmental Exposure to Cadmium: Health Risk Assessment and Its Associations with Hypertension and Impaired Kidney Function. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 29989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, G.; Dai, F.; Wang, W.; Zheng, W.; Zhang, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, Q. Health Risk Assessment of Chinese Consumers to Lead via Diet. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. 2017, 23, 1928–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åkesson, A.; Barregard, L.; Bergdahl, I.A.; Nordberg, G.F.; Nordberg, M.; Skerfving, S. Non-Renal Effects and the Risk Assessment of Environmental Cadmium Exposure. Environ. Health Perspect. 2014, 122, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corguinha, A.P.B.; de Souza, G.A.; Gonçalves, V.C.; Carvalho, C.d.A.; de Lima, W.E.A.; Martins, F.A.D.; Yamanaka, C.H.; Francisco, E.A.B.; Guilherme, L.R.G. Assessing Arsenic, Cadmium, and Lead Contents in Major Crops in Brazil for Food Safety Purposes. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2015, 37, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Abbreviation | Equation or Value | Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ecological Risk | |||

| Bioaccumulation factor | BAF | ||

| Concentration of avocado | This study | mg/kg | |

| Concentration in soil | This study | mg/kg | |

| Geo-accumulation index | |||

| Background value | As: 15; Cd: 1.0; Cr: 90; Hg: 0.25, Ni: 30; Pb: 70 | mg/kg | |

| Ecological risk | ER | ||

| Single pollution index | PI | ||

| Toxicity response coefficient | As: 10; Cd: 30; Cr: 2; Hg: 40, Ni: 2; Pb: 5 | ||

| Potential ecological risk index | RI | ||

| Health risk | |||

| Estimated daily intake | EDI | ) | mg/kgBw/day |

| Ingestion rate | IR | Lognormal (5th: 3.54 × 10−3; 50th: 2.38 × 10−2; 95%; 7.02 × 10−2) | kg/day |

| Body weight | Bw | LogNormal (5th: 45.3; 50th: 62.2; 95th: 85.4) | kgBw |

| Hazard quotient | HQ | EDI / RV | |

| Reference Value | RV | Cd: 0.001; Cr: 1.5; Ni: 0.02 | mg/kgBw/day |

| Hazard index | HI | ||

| Margin of exposure | MOE | BMDL%/EDI | |

| Benchmark dose | BMDL% | BMDL01 (Pb): 1.5 × 10−3 (Cardiovascular) | mg/kgBw/day |

| BMDL10 (Pb): 6.3 × 10−4 (Nephrotoxic) | mg/kgBw/day | ||

| Probability of exceedance | POE | ||

| Cancer risk | CR | EDI × SF | |

| Slope factor | SF | Cd: 0.38; Pb: 0.0085 | (mg/kgBw/day)−1 |

| Region | mg/kg | As | Cd | Cr | Hg | Ni | Pb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soil | |||||||

| Amazonas | Mean–S.D. | 42.414 ± 8.214 a | 0.271 ± 0.214 a | 7.458 ± 8.657 a | 0.075 ± 0.043 a | 4.415 ± 2.485 a | 9.049 ± 3.007 bc |

| Min–Max | 29.401–49.611 | <LOD–0.618 | 0.148–18.04 | <LOD–0.096 | 2.487–5.789 | 6.345–12.578 | |

| Ancash | Mean–S.D. | 45.114 ± 9.729 a | <LOD | 15.304 ± 7.248 a | 0.048 ± 0.057 a | 5.648 ± 1.514 a | 8.124 ± 1.243 c |

| Min–Max | 31.781–52.471 | <LOD | 2.568–22.689 | <LOD–0.087 | 3.471–7.048 | 7.004–9.904 | |

| Ayacucho | Mean–S.D. | 58.976 ± 7.625 a | 0.339 ± 0.056 a | 14.963 ± 8.942 a | 0.161 ± 0.014 a | 9.789 ± 2.348 a | 22.081 ± 7.451 a |

| Min–Max | 49.917–71.631 | <LOD–0.414 | 6.425–27.298 | <LOD–0.197 | 6.589–12.573 | 16.534–35.978 | |

| Cusco | Mean–S.D. | 52.674 ± 7.925 a | <LOD | 16.428 ± 10.245 a | 0.045 ± 0.075 a | 4.250 ± 3.247 a | 9.245 ± 2.864 bc |

| Min–Max | 49.911–69.366 | <LOD | 5.489–29.567 | <LOD–0.102 | 2.973–7.518 | 6.598–12.240 | |

| Huancavelica | Mean–S.D. | 34.014 ± 6.504 a | <LOD | 12.635 ± 13.425 a | 0.088 ± 0.064 a | 5.261 ± 2.516 a | 8.064 ± 1.974 c |

| Min–Max | 28.041–45.213 | <LOD | 0.178–26.751 | <LOD–0.138 | 3.048–7.802 | 7.189–9.678 | |

| Ica | Mean–S.D. | 42.414 ± 8.214 a | 0.384 ± 0.867 a | 38.182 ± 15.564 a | 0.140 ± 0.057 a | 5.826 ± 2.107 a | 10.007 ± 4.614 bc |

| Min–Max | 29.715–49.216 | <LOD–1.178 | 20.187–66.784 | <LOD–0.191 | 3.671–7.527 | 6.974–13.746 | |

| La Libertad | Mean–S.D. | 51.814 ± 18.321 a | 0.479 ± 0.964 a | 37.789 ± 18.476 a | 1.278 ± 0.046 a | 8.549 ± 1.932 a | 22.217 ± 4.831 ab |

| Min–Max | 32.784–72.647 | <LOD–1.578 | 23.451–64.789 | <LOD–1.386 | 5.987–11.278 | 17.726–28.694 | |

| Lima | Mean–S.D. | 76.174 ± 17.349 a | 0.548 ± 1.045 a | 35.612 ± 12.960 a | 0.367 ± 0.2448 a | 10.823 ± 4.850 a | 25.348 ± 6.015 a |

| Min–Max | 50.079–99.012 | <LOD–1.864 | 26.489–62.894 | <LOD–1.745 | 7.215–12.786 | 19.073–32.203 | |

| Avocado | |||||||

| Amazonas | Mean–S.D. | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 0.007 ± 0.001 a | <LOD | <LOD |

| Min–Max | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD–0.008 | <LOD | <LOD | |

| Ancash | Mean–S.D. | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 0.008 ± 0.002 a | <LOD | <LOD |

| Min–Max | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD–0.010 | <LOD | <LOD | |

| Ayacucho | Mean–S.D. | 0.154 ± 0.031 a | 0.011 ± 0.068 a | <LOD | 0.023 ± 0.004 a | 0.134 ± 0.018 a | 0.220 ± 0.046 a |

| Min–Max | <LOD–0.192 | <LOD–0.086 | <LOD | <LOD–0.029 | <LOD–0.146 | <LOD–0.272 | |

| Cusco | Mean–S.D. | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 0.005 ± 0.001 a | <LOD | <LOD |

| Min–Max | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD–0.007 | <LOD | <LOD | |

| Huancavelica | Mean–S.D. | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | 0.011 ± 0.003 a | <LOD | <LOD |

| Min–Max | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD | <LOD–0.060 | <LOD | <LOD | |

| Ica | Mean–S.D. | <LOD | 0.016 ± 0.059 a | <LOD | 0.020 ± 0.013 a | <LOD | <LOD |

| Min–Max | <LOD | <LOD–0.072 | <LOD | <LOD–0.041 | <LOD | <LOD | |

| La Libertad | Mean–S.D. | 0.125 ± 0.021 a | 0.028 ± 0.091 a | <LOD | 0.142 ± 0.013 a | 0.108 ± 0.021 a | 0.231 ± 0.046 a |

| Min–Max | <LOD–0.159 | <LOD–0.130 | <LOD | <LOD–0.157 | <LOD–0.132 | <LOD–0.283 | |

| Lima | Mean–S.D. | 0.152 ± 0.029 a | 0.033 ± 0.098 a | <LOD | 0.167 ± 0.0660 a | 0.147 ± 0.026 a | 0.325 ± 0.073 a |

| Min–Max | <LOD–0.184 | <LOD–0.120 | <LOD | <LOD–0.428 | <LOD–0.172 | <LOD–0.396 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yoplac-Navarro, M.; Grandez-Yoplac, D.E.; Rituay, P.; Campos Trigoso, J.A.; García, L.; Arellanos, E.; Ortiz-Porras, J.E.; Guadalupe, G.A. Ecological and Human Health Risk Assessment of Metals in Peruvian Avocados Using a Probabilistic Approach. Foods 2026, 15, 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010082

Yoplac-Navarro M, Grandez-Yoplac DE, Rituay P, Campos Trigoso JA, García L, Arellanos E, Ortiz-Porras JE, Guadalupe GA. Ecological and Human Health Risk Assessment of Metals in Peruvian Avocados Using a Probabilistic Approach. Foods. 2026; 15(1):82. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010082

Chicago/Turabian StyleYoplac-Navarro, Myryam, Dorila E. Grandez-Yoplac, Pablo Rituay, Jonathan Alberto Campos Trigoso, Ligia García, Erick Arellanos, Jorge Enrique Ortiz-Porras, and Grobert A. Guadalupe. 2026. "Ecological and Human Health Risk Assessment of Metals in Peruvian Avocados Using a Probabilistic Approach" Foods 15, no. 1: 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010082

APA StyleYoplac-Navarro, M., Grandez-Yoplac, D. E., Rituay, P., Campos Trigoso, J. A., García, L., Arellanos, E., Ortiz-Porras, J. E., & Guadalupe, G. A. (2026). Ecological and Human Health Risk Assessment of Metals in Peruvian Avocados Using a Probabilistic Approach. Foods, 15(1), 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010082