Fruits Granola Consumption May Contribute to a Reduced Risk of Cardiovascular Disease in Patients with Stage G2–4 Chronic Kidney Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

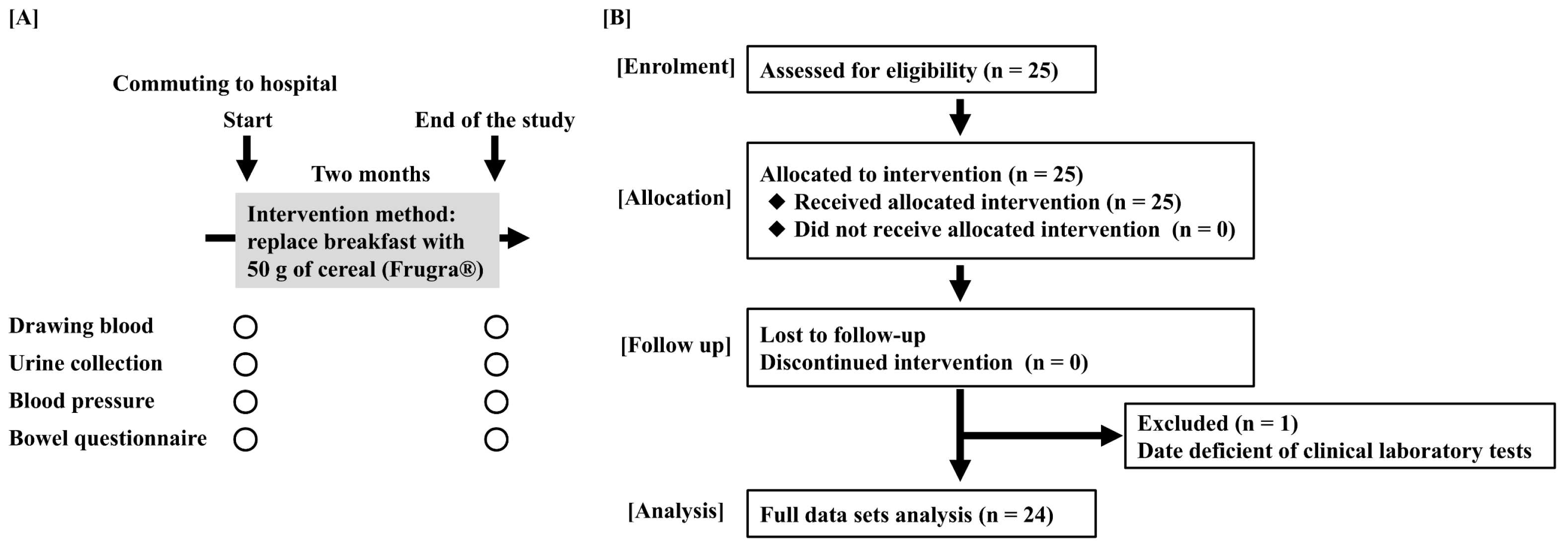

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

2.2. Measurement of Clinical and Biochemical Parameters

2.3. Study Procedures

2.4. Estimated Daily Salt Intake via Tanaka’s Formula

2.5. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Moderate CKD Patients Enrollment and the Primary Disease of CKD

3.2. The Effect of FGR Intake on Blood Pressure

3.3. The Effects of FGR Intake on Blood Parameters

3.4. The Effect of FGR Intake on the Urine Test

3.5. The Effect of FGR Intake on Bowel Movements

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kwoun, G.; Nangaku, M.; Mimura, I. Epigenetic memories induced by hypoxia in AKI-to-CKD transition. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2025, 29, 1712–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovesdy, C.P. Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease: An update 2022. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2022, 12, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaimori, J.Y.; Sakaguchi, Y.; Oka, T.; Isaka, Y. Plant-Dominant Low-Protein Diets: A Promising Dietary Strategy for Mitigating Disease Progression in People with Chronic Kidney Disease-A Comprehensive Review. Nutrients 2025, 17, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedla, F.M.; Brar, A.; Browne, R.; Brown, C. Hypertension in chronic kidney disease: Navigating the evidence. Int. J. Hypertens. 2011, 2011, 132405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Cai, R.; Sun, J.; Dong, X.; Huang, R.; Tian, S.; Wang, S. Diabetes mellitus as a risk factor for incident chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease in women compared with men: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Endocrine 2017, 55, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanbay, M.; Copur, S.; Siriopol, D.; Yildiz, A.B.; Berkkan, M.; Tuttle, K.R.; Zoccali, C. The risk for chronic kidney disease in metabolically healthy obese patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 53, e13878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, J.; Wu, H.X.; Nawaz, M.A.; Jiang, H.L.; Xu, S.N.; Huang, B.L.; Li, L.; Cai, J.M.; Zhou, H.D. Risk of incident chronic kidney disease in metabolically healthy obesity and metabolically unhealthy normal weight: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2024, 25, e13656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wakino, S.; Hasegawa, K.; Tamaki, M.; Minato, M.; Inagaki, T. Kidney-Gut Axis in Chronic Kidney Disease: Therapeutic Perspectives from Microbiota Modulation and Nutrition. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankowski, J.; Floege, J.; Fliser, D.; Böhm, M.; Marx, N. Cardiovascular Disease in Chronic Kidney Disease: Pathophysiological Insights and Therapeutic Options. Circulation 2021, 143, 1157–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, A.; Hirano, K.; Okuda, T.; Ikenoue, T.; Yamada, Y.; Yokoo, T.; Fukuma, S. An evaluation of stage-based survival and renal prognosis in the general super-older population of Japan. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Li, M.; Huang, Y. Association of dietary fiber intake with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in U.S. adults with metabolic syndrome: NHANES 1999–2018. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1659000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.W.; Baird, P.; Davis, R.H., Jr.; Ferreri, S.; Knudtson, M.; Koraym, A.; Waters, V.; Williams, C.L. Health benefits of dietary fiber. Nutr. Rev. 2009, 67, 188–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, Y.; Masutomi, H.; Ishihara, K.; Hartanto, T.; Lee, C.G.; Fukuda, S. The differential effect of two cereal foods on gut environment: A randomized, controlled, double-blind, parallel-group study. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1254712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurbau, A.; Noronha, J.C.; Khan, T.A.; Sievenpiper, J.L.; Wolever, T.M.S. The effect of oat β-glucan on postprandial blood glucose and insulin responses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 75, 1540–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Xia, J.; Yang, C.; Pan, D.; Xu, D.; Sun, G.; Xia, H. Effects of Oat Beta-Glucan Intake on Lipid Profiles in Hypercholesterolemic Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagasawa, H.; Ueda, S.; Otsuka, T.; Kaifu, K.; Ono, S.; Okuma, T.; Kobayashi, T.; Matsushita, S.; Kasai, T.; Dohi, T.; et al. Safety and efficacy of using cereal food (Frugra®) to improve blood pressure and bowel health in patients undergoing chronic hemodialysis: A pilot study. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2021, 147, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagasawa, H.; Suzuki, S.; Kobayashi, T.; Otsuka, T.; Okuma, T.; Matsushita, S.; Amano, A.; Shimizu, Y.; Suzuki, Y.; Ueda, S. Effect of fruits granola (Frugra®) consumption on blood pressure reduction and intestinal microbiome in patients undergoing hemodialysis. Hypertens. Res. 2024, 47, 3214–3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, C. Automated Hematology Analyzer XE-5000: Overview and Basic Performance. Sysmex J. Int. 2007, 17, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kidokoro, T.; Edamoto, K. Improvements in Physical Fitness are Associated with Favorable Changes in Blood Lipid Concentrations in Children. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2021, 20, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, V.J.; Smola, C.; Schmitt, P. Evaluation of the Beckman Coulter DxC 700 AU chemistry analyzer. Pract. Lab. Med. 2020, 18, e00148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niwa, T.; Takeda, N.; Tatematsu, A.; Maeda, K. Accumulation of indoxyl sulfate, an inhibitor of drug-binding, in uremic serum as demonstrated by internal-surface reversed-phase liquid chromatography. Clin. Chem. 1988, 34, 2264–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufmann, T.; Cox, E.G.M.; Wiersema, R.; Hiemstra, B.; Eck, R.J.; Koster, G.; Scheeren, T.W.L.; Keus, F.; Saugel, B.; van der Horst, I.C.C. Non-invasive oscillometric versus invasive arterial blood pressure measurements in critically ill patients: A post hoc analysis of a prospective observational study. J. Crit. Care 2020, 57, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, C.I.; Armani, R.G.; Canziani, M.E.; Ribeiro Dolenga, C.J.; Nakao, L.S.; Campbell, K.L.; Cuppari, L. Bowel Habits and the Association with Uremic Toxins in Non-Dialysis-Dependent Chronic Kidney Disease Patients. J. Ren. Nutr. 2020, 30, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Okamura, T.; Miura, K.; Kadowaki, T.; Ueshima, H.; Nakagawa, H.; Hashimoto, T. A simple method to estimate populational 24-h urinary sodium and potassium excretion using a casual urine specimen. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2002, 16, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffarian, D.; Fahimi, S.; Singh, G.M.; Micha, R.; Khatibzadeh, S.; Engell, R.E.; Lim, S.; Danaei, G.; Ezzati, M.; Powles, J. Global sodium consumption and death from cardiovascular causes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 624–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Xie, L.; Cheng, C.; Xue, F.; Sun, C. Triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and cardiovascular diseases. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1409653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Fan, H.; Zhang, S.; Chen, C.; You, Y.; Wang, C.; Li, J.; Luo, L.; Cheng, Y.; Zhou, M.; et al. Association of LDL-C/HDL-C ratio with coronary heart disease: A meta-analysis. Indian Heart J. 2024, 76, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surampudi, P.; Enkhmaa, B.; Anuurad, E.; Berglund, L. Lipid Lowering with Soluble Dietary Fiber. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2016, 18, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, D.J.; Wolever, T.M.; Rao, A.V.; Hegele, R.A.; Mitchell, S.J.; Ransom, T.P.; Boctor, D.L.; Spadafora, P.J.; Jenkins, A.L.; Mehling, C.; et al. Effect on blood lipids of very high intakes of fiber in diets low in saturated fat and cholesterol. N. Engl. J. Med. 1993, 329, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, S.; Lakshmipriya, N.; Vaidya, R.; Bai, M.R.; Sudha, V.; Krishnaswamy, K.; Unnikrishnan, R.; Anjana, R.M.; Mohan, V. Association of dietary fiber intake with serum total cholesterol and low density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in Urban Asian-Indian adults with type 2 diabetes. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 18, 624–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoe, S. Characteristics of Dietary Fiber in Cereals. J. Cook. Sci. Jpn. 2016, 49, 297–302. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D.; Feng, M.; Chu, Y.; Wang, S.; Shete, V.; Tuohy, K.M.; Liu, F.; Zhou, X.; Kamil, A.; Pan, D.; et al. The Prebiotic Effects of Oats on Blood Lipids, Gut Microbiota, and Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Mildly Hypercholesterolemic Subjects Compared with Rice: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 787797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, M.Y.; Shen, Y.C.; Chiu, H.F.; Ten, S.M.; Lu, Y.Y.; Han, Y.C.; Venkatakrishnan, K.; Yang, S.F.; Wang, C.K. Down-regulation of partial substitution for staple food by oat noodles on blood lipid levels: A randomized, double-blind, clinical trial. J. Food Drug Anal. 2019, 27, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felizardo, R.J.F.; Watanabe, I.K.M.; Dardi, P.; Rossoni, L.V.; Câmara, N.O.S. The interplay among gut microbiota, hypertension and kidney diseases: The role of short-chain fatty acids. Pharmacol. Res. 2019, 141, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortelote, G.G. Therapeutic strategies for hypertension: Exploring the role of microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids in kidney physiology and development. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzi, C.; Petrini, C.; Rizza, V.; Arrigo, G.; Napodano, P.; Paparella, M.; D’Amico, G. Urinary N-acetyl-beta-glucosaminidase excretion is a marker of tubular cell dysfunction and a predictor of outcome in primary glomerulonephritis. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2002, 17, 1890–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungbauer, C.G.; Uecer, E.; Stadler, S.; Birner, C.; Buchner, S.; Maier, L.S.; Luchner, A. N-acteyl-ß-D-glucosaminidase and kidney injury molecule-1: New predictors for long-term progression of chronic kidney disease in patients with heart failure. Nephrology 2016, 21, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobato, G.R.; Lobato, M.R.; Thomé, F.S.; Veronese, F.V. Performance of urinary kidney injury molecule-1, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin, and N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase to predict chronic kidney disease progression and adverse outcomes. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2017, 50, e6106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, G.; Altman, S. Increased serum N-acetyl-beta-D-glucosaminidase activity in human hypertension. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. A 1982, 4, 355–365. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, G.; Morioka, S.; Snyder, D.K. Increased serum and urinary N-acetyl-beta-D-glucosaminidase activity in human hypertension: Early indicator of renal dysfunction. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. A 1984, 6, 879–896. [Google Scholar]

- Lisowska-Myjak, B.; Krych, A.; Kołodziejczyk, A.; Pachecka, J.; Gaciong, Z. Urinary proteins, N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase activity and estimated glomerular filtration rate in hypertensive patients with normoalbuminuria and microalbuminuria. Nephrology 2011, 16, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, P.; Azevedo, O.; Pinto, R.; Marino, J.; Baker, R.; Cardoso, C.; Ducla Soares, J.L.; Hughes, D. New biomarkers defining a novel early stage of Fabry nephropathy: A diagnostic test study. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2017, 121, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novak, R.; Salai, G.; Hrkac, S.; Vojtusek, I.K.; Grgurevic, L. Revisiting the Role of NAG across the Continuum of Kidney Disease. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renke, M.; Tylicki, L.; Rutkowski, P.; Neuwelt, A.; Larczyński, W.; Ziętkiewicz, M.; Aleksandrowicz, E.; Lysiak-Szydłowska, W.; Rutkowski, B. Atorvastatin improves tubular status in non-diabetic patients with chronic kidney disease—Placebo controlled, randomized, cross-over study. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2010, 57, 547–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fruits Granola (50 g) | |

|---|---|

| Energy (kcal) | 220 |

| Protein (g) | 3.9 |

| Lipid (g) | 7.7 |

| Carbohydrate glucose (g) | 31.6 |

| 4.5 |

| Salt intake (g) | 0.24 |

| Potassium (mg) | 135 |

| Calcium (mg) | 16 |

| Phosphorus (mg) | 83 |

| Iron (mg) | 5.0 |

| Vitamin A (μg) | 257 |

| Vitamin D (μg) | 1.84 |

| Vitamin B1 (mg) | 0.40 |

| Niacin (mg) | 4.4 |

| Vitamin B6 (mg) | 0.44 |

| Vitamin B12 (μg) | 0.80 |

| Folic acid (μg) | 80 |

| Pantothenic acid (mg) | 1.6 |

| Patients with CKD (number) | 24 |

| Male, % (number) | 83.3% (20) |

| Age (year, mean ± SD) | 66.8 ± 9.7 |

| Height (m, mean ± SD) | 1.68 ± 0.07 |

| Body weight (kg, mean ± SD) | 78.5 ± 17.7 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2, mean ± SD) | 27.7 ± 5.1 |

| Primary disease | |

| 87.5% (21) |

| 8.3% (2) |

| 4.2% (1) |

| CKD stage | |

| 4.2% (1) |

| 45.8% (11) |

| 25.0% (6) |

| 25.0% (6) |

| Start | End of the Study | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 128.9 ± 11.4 | 124.3 ± 9.6 ** | <0.01 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 79.6 ± 16.4 | 77.4 ± 8.3 | 0.06 |

| Start | End of the Study | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| White blood cells (count/μL) | 6608 ± 2279 | 6467 ± 1196 | 0.82 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 14.2 ± 2.1 | 14.3 ± 2.0 | 0.41 |

| Platelet (×104/μL) | 19.8 ± 4.5 | 20.5 ± 4.9 | 0.20 |

| AST (U/L) | 23.8 ± 13.0 | 22.5 ± 7.7 | 0.71 |

| ALT (U/L) | 25.2 ± 14.7 | 23.2 ± 10.7 | 0.26 |

| γ-GTP (U/L) | 35.6 ± 25.4 | 34.3 ± 23.8 | 0.25 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.5 ± 0.3 | 3.7 ± 0.3 | 0.95 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 24.1 ± 10.3 | 24.6 ± 10.7 | 0.68 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 0.62 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73m2) | 41.4 ± 13.5 | 42.2 ± 14.2 | 0.77 |

| Serum uric acid (mg/dL) | 5.4 ± 1.4 | 5.3 ± 1.4 | 0.52 |

| Blood glucose (mg/dL) | 128.4 ± 25.7 | 134.2 ± 33.6 | 0.20 |

| HbA1c (%) | 6.5 ± 0.8 | 6.5 ± 0.7 | 0.97 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 104.6 ± 25.4 | 98.2 ± 23.9 * | 0.03 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 48.2 ± 13.0 | 49.4 ± 12.7 | 0.15 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dL) | 178.3 ± 91.4 | 175.6 ± 57.4 | 0.69 |

| LDL-C/HDL-C (ratio) | 2.3 ± 0.8 | 2.1 ± 0.6 ** | <0.01 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 140.3 ± 2.2 | 140.3 ± 2.5 | 0.96 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 4.4 ± 0.5 | 4.5 ± 0.5 | 0.19 |

| Chloride (mmol/L) | 104.8 ± 3.5 | 104.4 ± 2.8 | 0.40 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 9.4 ± 0.3 | 9.4 ± 0.4 | 0.12 |

| Phosphorus (mg/dL) | 3.3 ± 0.4 | 3.3 ± 0.5 | 0.67 |

| Iron (μg/dL) | 91.3 ± 27.5 | 86.4 ± 25.6 | 0.31 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 243.4 ± 157.9 | 222.4 ± 140.5 * | 0.02 |

| Indoxyl sulfate (μg/mL) | 2.1 ± 1.4 | 2.3 ± 1.7 | 0.43 |

| Start | End of the Study | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urinary protein (mg/dL) | 0.7 ± 1.0 | 0.7 ± 0.9 | 0.85 |

| Urinary albumin (mg/gCr) | 456.1 ± 694.0 | 408.2 ± 581.2 | 0.70 |

| Urinary creatinine (mg/dL) | 110.0 ± 56.4 | 90.1 ± 48.2 * | 0.03 |

| Alb/Cre (mg/gCr) | 9.5 ± 27.5 | 7.2 ± 12.3 | 0.22 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 83.5 ± 46.5 | 83.1 ± 31.5 | 0.62 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 48.2 ± 13.0 | 49.4 ± 12.7 | 0.83 |

| Chloride (mmol/L) | 85.4 ± 45.6 | 89.0 ± 33.1 | 0.35 |

| Estimated NaCl intake (g/day) | 8.4 ± 2.3 | 9.2 ± 0.8 * | 0.03 |

| NAG (U/L) | 11.0 ± 8.9 | 7.6 ± 4.0 ** | <0.01 |

| Start | End of the Study | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bowel movement frequency/week | 6.0 ± 2.1 | 7.3 ± 2.0 ** | <0.01 |

| Bristol stool form scale (BSS) | |||

| 4 | 0 | 0.04 |

| 20 | 24 * | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Okuma, T.; Nagasawa, H.; Otsuka, T.; Masutomi, H.; Matsushita, S.; Suzuki, Y.; Ueda, S. Fruits Granola Consumption May Contribute to a Reduced Risk of Cardiovascular Disease in Patients with Stage G2–4 Chronic Kidney Disease. Foods 2025, 14, 4346. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244346

Okuma T, Nagasawa H, Otsuka T, Masutomi H, Matsushita S, Suzuki Y, Ueda S. Fruits Granola Consumption May Contribute to a Reduced Risk of Cardiovascular Disease in Patients with Stage G2–4 Chronic Kidney Disease. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4346. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244346

Chicago/Turabian StyleOkuma, Teruyuki, Hajime Nagasawa, Tomoyuki Otsuka, Hirofumi Masutomi, Satoshi Matsushita, Yusuke Suzuki, and Seiji Ueda. 2025. "Fruits Granola Consumption May Contribute to a Reduced Risk of Cardiovascular Disease in Patients with Stage G2–4 Chronic Kidney Disease" Foods 14, no. 24: 4346. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244346

APA StyleOkuma, T., Nagasawa, H., Otsuka, T., Masutomi, H., Matsushita, S., Suzuki, Y., & Ueda, S. (2025). Fruits Granola Consumption May Contribute to a Reduced Risk of Cardiovascular Disease in Patients with Stage G2–4 Chronic Kidney Disease. Foods, 14(24), 4346. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244346