Spatiotemporal Patterns of Aquatic Product Risks in China Based on Entropy-Weighted TOPSIS

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Study Methods

2.2. Indicator Selection

- (1)

- Non-compliance rate: When test values are greater than or equal to national or international maximum permitted levels, the sample is deemed non-compliant. This refers to the percentage of non-compliant results detected relative to the total number of tests conducted.

- (2)

- Detection rate: This represents the percentage of samples yielding detectable levels of the risk substance relative to the total number tested.

- (3)

- Qualification degree: For risk indicators deemed compliant in testing results, the closer the detected value approaches the national standard limit, the greater the likelihood of non-compliance and the higher the risk. Conversely, the closer the detected value approaches the laboratory’s detection limit—that is, the further it is from the national standard limit—the lower the likelihood of non-compliance and the lower the risk.

- (4)

- Hazard degree: This denotes the gravity of a hazard factor’s impact on consumer health, typically quantified using three indicators—health guidance values, carcinogenicity, and median lethal dose (LD50) [28]. Where all three risk indicators are assigned values for a given hazard, the highest value is selected as the severity score. The severity scoring table for food hazards is provided in the Supplementary Materials, Table S1.

2.3. Analytical Methods

2.3.1. Construction of Risk Classification Model Based on the Entropy-Weighted TOPSIS Method

Calculation of Weights Using the Entropy Weight Method

Calculation of Relative Proximity Using the TOPSIS Method

2.3.2. Pareto Principle

2.3.3. Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis

Global Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis

Local Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis

2.3.4. Spatiotemporal Analysis

2.3.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

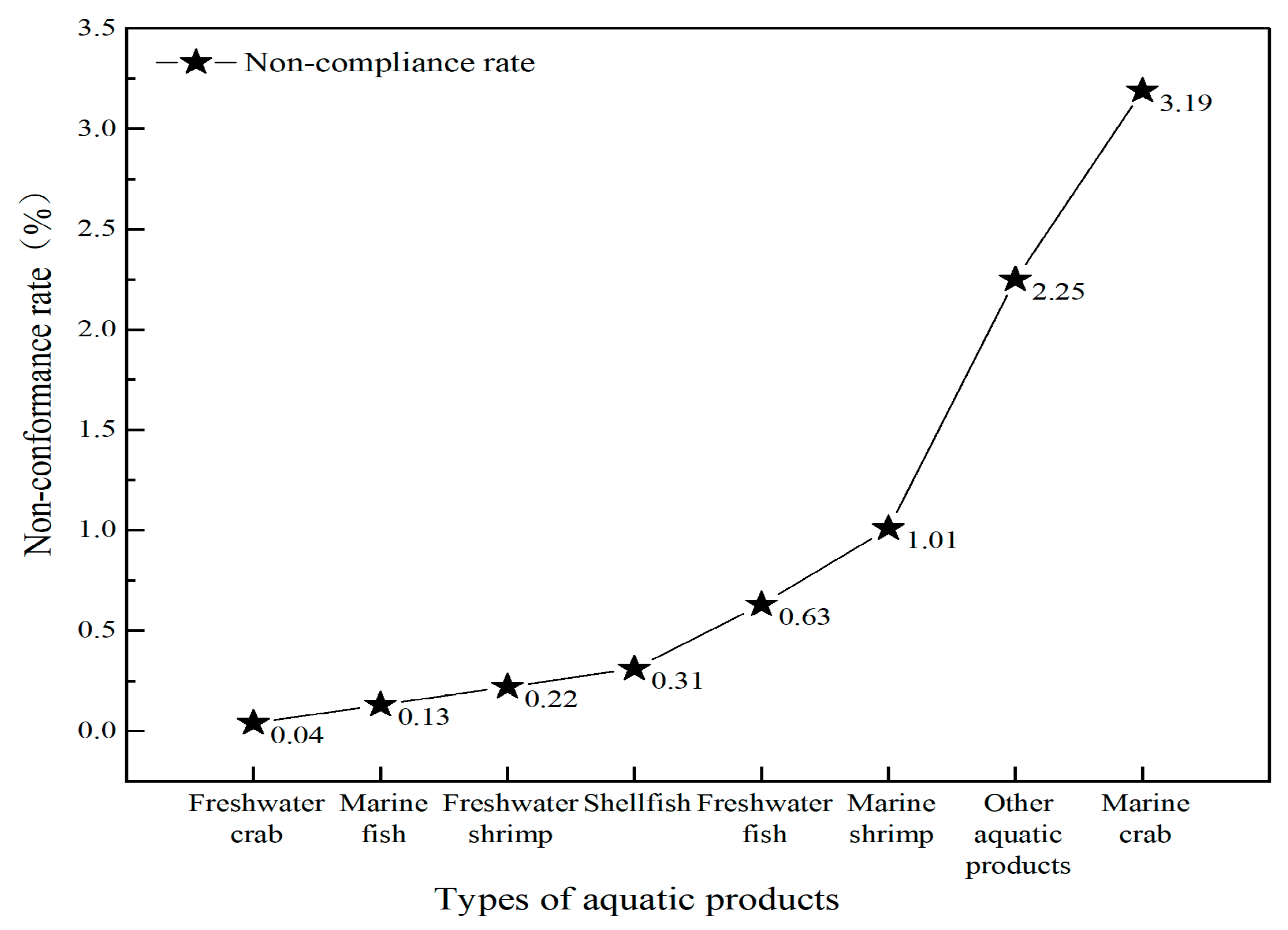

3.1. Detection Results of Risk Substances in Aquatic Products

3.2. Temporal Distribution of Risky Substances in Aquatic Products

3.2.1. Veterinary Drugs

3.2.2. Heavy Metals

3.2.3. Prohibited Drugs

3.2.4. Quality Indicators

3.2.5. Additives

3.3. Spatial Distribution of Risk Substances in Aquatic Products

3.3.1. Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis

Global Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis

Local Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis

3.3.2. Sampling Location Analysis

3.3.3. Sampling Venue Analysis

3.4. Spatiotemporal Analysis of Risk Substances in Aquatic Products

4. Discussion

4.1. Core Risk Substances and Their Health Risks

4.2. Risk Variations Across Different Stages and Their Spatiotemporal Distribution Patterns

4.3. Comparative Analysis of Research Frameworks

4.4. The Importance and Value of Risk Classification and Spatiotemporal Analysis Models in Risk Prevention and Control

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hu, S.L.; Chen, X.C.; Xue, Y.X.; Zhi, L.Y.; Yang, Y.H.; Zhu, Y.G.; Xue, X.M. Metal(loid)s in aquatic products and their potential health risk. Expo. Health 2024, 16, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.X.; Feng, Q.H.; Fu, H.X.; Ren, K.; Shang, W.T.; Li, C.; Zhang, X.S.; Nga, M.T.T.; He, Y.F. Current trends and perspectives on aquatic-derived protein: A focus on structure-technofunctional properties relationship and application for food preservation. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 151, 104651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.T.; Li, Q.; Bao, Y.L.; Tan, Y.Q.; Lametsch, R.; Hong, H.; Luo, Y.K. Recent advances on characterization of protein oxidation in aquatic products: A comprehensive review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 1572–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, J.R. Aquatic Food Products: Processing Technology and Quality Control. Foods 2024, 13, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.P.; Song, Y.; Cong, P.X.; Cao, Y.R.; Xu, J.; Xue, C.H. A systematic review of drying in aquatic products. Rev. Aquac. 2024, 16, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Xiao, M.; Sudo, N.; Liu, Q.H. Bioactive peptides of marine organisms: Roles in the reduction and control of cardiovascular diseases. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 5271–5284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokubun, K.; Nemoto, K.; Yamakawa, Y. Fish intake may affect brain structure and improve cognitive ability in healthy people. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2020, 12, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smolińska, K.; Szopa, A.; Sobczyński, J.; Serefko, A.; Dobrowolski, P. Nutritional Quality Implications: Exploring the Impact of a Fatty Acid-Rich Diet on Central Nervous System Development. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budhathoki, M.; Campbell, D.; Belton, B.; Newton, R.; Li, S.; Zhang, W.; Little, D. Factors influencing consumption behaviour towards aquatic food among Asian consumers: A systematic scoping review. Foods 2022, 11, 4043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishery and Fishery Administration Bureau of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs. 2023 national fishery economic statistics bulletin. Fish. Sci. Technol. Inf. 2024, 51, 269. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, S.J.; Niu, B.; Chen, J.H.; Deng, X.J.; Chen, Q. Risk analysis of veterinary drug residues in aquatic products in the Yangtze river delta of China. J. Food Prot. 2021, 84, 1228–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, L.; Wang, L. The microbial safety of fish and fish products: Recent advances in understanding its significance, contamination sources, and control strategies. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 738–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saravanan, P.; Saravanan, V.; Rajeshkannan, R.; Arnica, G.; Rajasimman, M.; Gurunathan, B.; Pugazhendhi, A. Comprehensive review on toxic heavy metals in the aquatic system: Sources, identification, treatment strategies, and health risk assessment. Environ. Res. 2024, 258, 119440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.L.; Wu, J.P.; Yu, B.J.; Dong, K.F.; Ma, D.; Xiao, G.X.; Zhang, C.Z. Heavy metals in aquatic products and the health risk assessment to population in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 22708–22719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sall, M.L.; Diaw, A.K.D.; Gningue-Sall, D.; Efremova Aaron, S.; Aaron, J.-J. Toxic heavy metals: Impact on the environment and human health, and treatment with conducting organic polymers, a review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 29927–29942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, T.Q.; Liu, T.Q.; Dong, W.; Liu, Y.J.; Hao, C.; Zhang, Q.C. Prediction of safety risk levels of veterinary drug residues in freshwater products in China based on transformer. Foods 2022, 11, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Steele, J.C.; Meng, X.Z. Usage, residue, and human health risk of antibiotics in Chinese aquaculture: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 223, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Meng, S.L.; Fang, L.X.; Li, Z.H.; Yang, R.N.; Qiu, L.P.; Zhong, L.Q.; Song, C. Intra-species differences shape differences of enrofloxacin residues and its degradation products in tilapia: A precise risk assessment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 476, 135151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.S.; Lee, S.B.; Shin, D.; Jeong, J.; Hong, J.H.; Rhee, G.S. Occurrence of veterinary drug residues in farmed fishery products in South Korea. Food Control 2018, 85, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Mo, P.; Luo, Y.S.; Yang, P.H. Strategies for solving the issue of malachite green residues in aquatic products: A review. Aquac. Res. 2023, 2023, 8578570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okocha, R.C.; Olatoye, I.O.; Adedeji, O.B. Food safety impacts of antimicrobial use and their residues in aquaculture. Public Health Rev. 2018, 39, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okeke, E.S.; Chukwudozie, K.I.; Nyaruaba, R.; Ita, R.E.; Oladipo, A.; Ejeromedoghene, O.; Atakpa, E.O.; Agu, C.V.; Okoye, C.O. Antibiotic resistance in aquaculture and aquatic organisms: A review of current nanotechnology applications for sustainable management. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 69241–69274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.X.; Yu, W.X.; Xue, F.; Wu, Y. Characteristics of heavy metal distribution and health risk evaluation of marine products in the sea ares of Wenzhou, China. Acta Agric. Zhejiangensis 2025, 37, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Ku, H.H.; Lin, P.P.; Ling, M.P. Assessment of potential human health risks in aquatic products based on the heavy metal hazard decision tree. BMC Bioinform. 2021, 22, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.Q.; Ou, Y.J.; Florence, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.Y.; Zhang, Y.H.; Liu, L.; Lei, J.B.; Huang, L.L.; Wu, S.X. Exploration of the Development of a Food Safety Risk Index System for Chemical Contamination of Aquatic Products. Food Control 2025, 172, 111189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.M.; Zhang, Q.H.; Tao, G.C.; Hu, K. Research on the evolutionary patterns of quality and safety ofmeat product in china based on risk ranking technology. Sci. Technol. Food Ind. 2024, 45, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Shun, X.H.; Lin, C.S.; Tao, G.C.; Hu, K. Establishment of tea risk rank model based on the perspective of time, space and risk substances. J. Food Saf. Qual. 2022, 13, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S.; Duan, Z.; Liang, J.; Deng, X.; Wen, J.; Huang, Q.; Huang, R.; Yang, X. Risk ranking method for chemical and biological hazards in food based on semi-quantitative risk assessment. Chin. J. Food Hyg. 2015, 27, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.C.; Yu, S.Y. Study on the risk level of food production enterprise based on TOPSIS method. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 42, e29721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puertas, R.; Marti, L.; Garcia-Alvarez-Coque, J.-M. Food supply without risk: Multicriteria analysis of institutional conditions of exporters. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falsafi, S.R.; Maghsoudlou, Y.; Aalami, M.; Jafari, S.M.; Raeisi, M.; Nishinari, K.; Rostamabadi, H. Application of multi-criteria decision-making for optimizing the formulation of functional cookies containing different types of resistant starches: A physicochemical, organoleptic, in-vitro and in-vivo study. Food Chem. 2022, 393, 133376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, D.; Dutta, G.; Saha, K. Assessing and ranking international markets based on stringency of food safety measures: Application of fuzzy AHP-TOPSIS method. Br. Food J. 2023, 125, 262–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.L.; Zhang, Y.K.; Li, Y. A novel multi-dimensional evaluation framework and spatiotemporal analysis of shipping cities based on entropy-weighted TOPSIS method. J. Knowl. Econ. 2025, 16, 5516–5547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Ahmad, M.; Zhang, H.T.; Guo, J.X. Effects of science and technology finance on green total factor productivity in China: Insights from an empirical spatial Durbin model. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 15, 7280–7306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.M.; Hu, K.; Xu, S.; Tao, G.C.; Zhang, Q.H. Establishment of dairy product risk rank model based on the perspective of time, space, and potential contaminants. Qual. Assur. Saf. Crops Foods 2023, 15, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.Z. Research on Dynamic Risk Analysis System of Imported Food Based on Entropy Method. Ph.D. Thesis, Tianjin University of Science and Technology, Tianjin, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, N.; Wang, H.; Mao, W.F.; Zhou, P.P. Establishment and application of health risk ranking model for heavy metals in aquatic products. Chin. J. Food Hyg. 2020, 32, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.L.; Dai, F.; Zhang, S.F.; Zhang, S.Q. Investigation and analysis of veterinary drug residues and heavy metals inanimal aquatic products in Suzhou. J. Food Saf. Qual. 2019, 10, 2174–2180. [Google Scholar]

- Qing, Y.; Yang, J.Q.; Zhu, Y.S.; Li, Y.Z.; Ma, W.R.; Zhang, C.; Li, X.; Wu, M.; Wang, H.; Kauffman, A.E. Cancer risk and disease burden of dietary cadmium exposure changes in Shanghai residents from 1988 to 2018. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 734, 139411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lao, Y.M.; Qu, C.L.; Zhang, B.; Jin, H. Development and validation of single-step microwave-assisted digestion method for determining heavy metals in aquatic products: Health risk assessment. Food Chem. 2023, 402, 134500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonsignore, M.; Manta, D.S.; Mirto, S.; Quinci, E.M.; Ape, F.; Montalto, V.; Gristina, M.; Traina, A.; Sprovieri, M. Bioaccumulation of heavy metals in fish, crustaceans, molluscs and echinoderms from the Tuscany coast. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 162, 554–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.L.; Lv, L.Y.; An, M.; Wang, T.; Li, M.; Yu, Y. Heavy metals in marine food web from Laizhou Bay, China: Levels, trophic magnification, and health risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 841, 156818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, M.X.; Mo, X.; Shi, Y.F.; Ye, H.L.; Huang, D.M.; Li, S.M.; Fang, C.L. Accumulation status of typical heavy metals in major seafood from Sanmen Bay of the East China Sea. Asian J. Ecotoxicol. 2024, 19, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, B.J.; Ying, T.; Chao, L.Y.; Sheng, H.G. Relative bioavailability of cadmium in aquatic products and its application on the cadmium exposure risk assessment. Shanghai J. Prev. Med. 2024, 36, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalagbor, A.; Martins, B.; Obelema, B.; Akpotayire, S. Concentration of Dietary Exposure and Health Risk Assessment of Ni, Cd and Pb in Periwinkles Clams and Nile tilapia Harvested from Selected Communities in the Niger Delta Region, Nigeria. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manag. 2025, 29, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, K.H.H.; Mustafa, F.S.; Omer, K.M.; Hama, S.; Hamarawf, R.F.; Rahman, K.O. Heavy metal pollution in the aquatic environment: Efficient and low-cost removal approaches to eliminate their toxicity: A review. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 17595–17610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, J.X.; Wang, Y.; Lin, H.; Sun, Y.M.; Pan, Y.N.; Qiao, J.-Q.; Lian, H.-Z.; Xu, C.-X. Residue screening and analysis of enrofloxacin and its metabolites in real aquatic products based on ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography coupled with high resolution mass spectrometry. Food Chem. 2023, 404, 134757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.T.; Chen, J.A.; Ren, T.T.; Tang, Y.W.; Wang, X.H.; Wang, S. Recent progress in detection methods of enrofloxacin in foods. Food Sci. 2022, 43, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 31650-2019; National Food Safety Standard—Maximum Residue Limits for Veterinary Drugs in Food. Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of China, National Health Commission, State Administration for Market Regulation: Beijing, China, 2020. (In Chinese)

- Zheng, Y.; Li, J.J.; Yona, A.; Wang, X.F.; Li, X.; Yuan, J.L.; Xu, G.C. Integrated Monitoring of Water Quality, Metal Ions, and Antibiotic Residues, with Isolation and Optimization of Enrofloxacin-Degrading Bacteria in American Shad (Alosa sapidissima) Aquaculture Systems. J. Xenobiotics 2025, 15, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, R.; Wang, X.; Ren, Y.; Li, S.; Guo, W.; Liu, J.; Mu, Y.; Wang, X.; Xia, S.; Cheng, B. Effect of water temperature on the depletion of enrofloxacin and its metabolite ciprofloxacin in largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) tissue following repeated oral administrations. Aquaculture 2025, 612, 743154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Fang, H.; Li, J.; Shi, S.; Pu, Y.; He, Y.; Liu, Z.; Cheng, L.; Liu, H.; Lin, T. Determination and risk assessment of diazepam residues in aquatic products from China. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2025, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Lu, S.; Huang, C.; Wang, F.; Ren, Y.; Cao, H.; Lin, Q.; Tan, Z.; Wen, X. A survey of chloramphenicol residues in aquatic products of Shenzhen, South China. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2021, 38, 914–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, R.C.; Xiao, G.Q.; Miao, J.J.; Zhou, Y.Y.; Li, Z.Y.; He, Z.H.; Zhang, N.; Song, A.M.; Pan, L.Q. Toxicity assessment and detoxification metabolism of sodium pentachlorophenol (PCP-Na) on marine economic species: A case study of Moerella iridescens and Exopalaemon carinicauda. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 113587–113599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G.X.; Ding, S.H.; Zhang, J.Y.; Gu, L.; Zhai, W.L.; Kong, C. Research progress on metabolites of nitrofurazone in aquatic products. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalifa, H.O.; Shikoray, L.; Mohamed, M.-Y.I.; Habib, I.; Matsumoto, T. Veterinary drug residues in the food chain as an emerging public health threat: Sources, analytical methods, health impacts, and preventive measures. Foods 2024, 13, 1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.P.; Sun, Y.; Sang, S.Y.; Jia, L.L.; Ou, C.R. Emerging approach for fish freshness evaluation: Principle, application and challenges. Foods 2022, 11, 1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, H.H.; Zhou, X.J.; Xiang, X.W.; Zhang, J.; Song, L.L.; Li, R.X.; Fu, M.N.; Huang, Y.Z. Changes in total volatile basic nitrogen and biogenic amines in 4 kinds of marine products during refrigerated storage. J. Food Saf. Qual. 2022, 13, 2794–2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekhit, A.E.D.A.; Giteru, S.G.; Holman, B.W.; Hopkins, D.L. Total volatile basic nitrogen and trimethylamine in muscle foods: Potential formation pathways and effects on human health. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 3620–3666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntzimani, A.; Angelakopoulos, R.; Stavropoulou, N.; Semenoglou, I.; Dermesonlouoglou, E.; Tsironi, T.; Moutou, K.; Taoukis, P. Seasonal pattern of the effect of slurry ice during catching and transportation on quality and shelf life of gilthead sea bream. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Z.; Guan, Z.Q.; Li, M. Effect of pre-cooling conditions on fresh-keeping to ice-temperature tilapia fillets. Food Mach. 2019, 35, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, N.; Rotabakk, B.T.; Lerfall, J. Mild processing of seafood—A review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 340–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Pan, C.; Chen, S.; Xue, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Y. Effects of modified atmosphere packaging with different gas ratios on the quality changes of golden pompano (Trachinotus ovatus) fillets during superchilling storage. Foods 2022, 11, 1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, X.G.; Zuo, Z.J.; Zhang, R.C.; Luo, S.; Chi, Y.Z.; Yuan, X.Y.; Song, C.W.; Wu, Y.J. New advances in biological preservation technology for aquatic products. npj Sci. Food 2025, 9, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Chen, X.; Yu, B.; Liu, S.X.; Han, X.O.; Hua, Z.G. Risk assessment of dietary exposure to sulfur dioxide in some foods in Liaoning province. J. Food Saf. Qual. 2021, 12, 9292–9298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonone, S.S.; Jadhav, S.; Sankhla, M.S.; Kumar, R. Water contamination by heavy metals and their toxic effect on aquaculture and human health through food Chain. Lett. Appl. NanoBioScience 2020, 10, 2148–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunusa, M.A.; Igwe, E.C.; Mofoluke, A.O. Heavy metals contamination of water and fish-a review. Fudma J. Sci. 2023, 7, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazman, M.M.; Ustaoğlu, F.; Aydın, H.; Yüksel, B. Interlinking Metal Pollution, Sources, and Health Hazards in Çamlıgöze Aquaculture Waters, Türkiye: An Application in Environmental Forensics. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 108183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschelli, L.; Berardinelli, A.; Dabbou, S.; Ragni, L.; Tartagni, M. Sensing technology for fish freshness and safety: A review. Sensors 2021, 21, 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Du, H.; Zhao, Z.; Wu, Y.; Cao, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, Y. Risk assessment model system for aquatic animal introduction based on analytic hierarchy process (AHP). Animals 2023, 13, 2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Feng, Q. Multidimensional Risk Assessment of China’s Grain Supply Chain with Entropy Weight TOPSIS Method. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 242, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hazardous Substance | Distribution | Catering | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sorting | Sorting | |||

| Cadmium | 0.595 | 1 | 0.707 | 1 |

| Enrofloxacin | 0.579 | 2 | 0.689 | 2 |

| Total volatile basic nitrogen | 0.45 | 3 | 0.429 | 3 |

| Sulfur dioxide | 0.333 | 4 | 0.092 | 31 |

| Diazepam | 0.291 | 5 | 0.155 | 10 |

| Methylmercury | 0.274 | 6 | 0.308 | 4 |

| Malachite green | 0.261 | 7 | 0.154 | 11 |

| Furazolidone metabolites | 0.26 | 8 | 0.167 | 9 |

| Chloramphenicol | 0.256 | 9 | 0.147 | 12 |

| Nitrofurazone metabolites | 0.253 | 10 | 0.171 | 8 |

| Sodium Pentachlorophenate | 0.249 | 11 | 0.237 | 5 |

| Metronidazole | 0.248 | 12 | 0.141 | 13 |

| Nitrofurantoin metabolites | 0.247 | 13 | 0.139 | 16 |

| Furaltadone metabolites | 0.247 | 14 | 0.139 | 15 |

| Sarafloxacin | 0.243 | 15 | 0.13 | 17 |

| Ofloxacin | 0.243 | 16 | 0.123 | 18 |

| Polychlorinated Biphenyls | 0.239 | 17 | 0.104 | 27 |

| Danofloxacin | 0.238 | 18 | 0.118 | 23 |

| Flumequine | 0.231 | 19 | 0.118 | 24 |

| Difloxacin | 0.228 | 20 | 0.123 | 20 |

| Oxolinic acid | 0.205 | 21 | 0.123 | 19 |

| Inorganic arsenic | 0.2 | 22 | 0.213 | 6 |

| Chromium | 0.186 | 23 | 0.178 | 7 |

| Histamine | 0.15 | 24 | 0.088 | 32 |

| Lead | 0.113 | 25 | 0.14 | 14 |

| Deltamethrin | 0.105 | 26 | 0.104 | 26 |

| Cypermethrin | 0.094 | 27 | 0.095 | 28 |

| Trimethoprim | 0.065 | 28 | 0.045 | 33 |

| Florfenicol | 0.065 | 29 | 0.094 | 29 |

| Sulfonamides (total) | 0.052 | 30 | 0.036 | 34 |

| Pefloxacin | 0.045 | 31 | 0.123 | 21 |

| Oxytetracycline/chlortetracycline/tetracycline (sum) | 0.035 | 32 | 0.093 | 30 |

| Norfloxacin | 0.024 | 33 | 0.123 | 22 |

| Lomefloxacin | 0.023 | 34 | 0.118 | 25 |

| Risk Level | Value Range | Grading |

|---|---|---|

| [0, 10%) | [0, 0.0513) | Lowest |

| [10%, 40%) | [0.0513, 0.1272) | Lower |

| [40%, 70%) | [0.1272, 0.2402) | Medium |

| [70%, 90%) | [0.2402, 0.3426) | Higher |

| [90%, 100%] | [0.3426, 0.7070] | Highest |

| (a) | |||

| Category | Hazardous Substances | Grading | |

| Distribution | Catering | ||

| Prohibited drugs | Chloramphenicol | Higher | Medium |

| Furazolidone metabolites | Higher | Medium | |

| Malachite Green | Higher | Medium | |

| Nitrofurazone metabolites | Higher | Medium | |

| Sodium pentachlorophenate | Higher | Higher | |

| Nitrofurantoin metabolites | Higher | Medium | |

| Diazepam | Higher | Medium | |

| Furaltadone metabolites | Higher | Medium | |

| (b) | |||

| Category | Hazardous Substances | Grading | |

| Distribution | Catering | ||

| Veterinary drugs | Enrofloxacin | Highest | Highest |

| Sulfonamides (Total) | Lower | Lowest | |

| Trimethoprim | Lower | Lowest | |

| Florfenicol | Lower | Lower | |

| Oxytetracycline/chlortetracycline/tetracycline (Sum) | Lowest | Lower | |

| Metronidazole | Higher | Medium | |

| Ofloxacin | Higher | Lower | |

| Norfloxacin | Lowest | Lower | |

| Pefloxacin | Lowest | Lower | |

| Lomefloxacin | Lowest | Lower | |

| Deltamethrin | Lower | Lower | |

| Cypermethrin | Lower | Lower | |

| Difloxacin | Medium | Lower | |

| Oxolinic acid | Medium | Lower | |

| Flumequine | Medium | Lower | |

| Danofloxacin | Medium | Lower | |

| Sarafloxacin | Higher | Medium | |

| (c) | |||

| Category | Hazardous Substances | Grading | |

| Distribution | Catering | ||

| Additives | Sulfur dioxide | Higher | Lower |

| Organic pollutants | Polychlorinated biphenyls | Medium | Lower |

| Quality indicators | Total volatile basic nitrogen | Highest | Highest |

| Histamine | Medium | Lower | |

| Heavy metals | Cadmium | Highest | Highest |

| Chromium | Medium | Medium | |

| Lead | Lower | Medium | |

| Inorganic arsenic | Medium | Medium | |

| Methylmercury | Higher | Higher | |

| Type of Aquatic Products | Percentage of Major Non-Compliant Items |

|---|---|

| Seawater crab | Cadmium (99.90%), chloramphenicol (0.10%) |

| Other aquatic products | Enrofloxacin (67.83%), furazolidone metabolites (11.43%), nitrofurazone metabolites (10.67%), cadmium (5.97%) |

| Seawater shrimp | Cadmium (82.47%), enrofloxacin (6.16%), furazolidone metabolites (5.34%) |

| Freshwater fish | Enrofloxacin (71.35%), diazepam (9.91%), malachite green (7.80%) |

| Shellfish | Chloramphenicol (52.44%), cadmium (20.89%), florfenicol (8.44%), enrofloxacin (8.44%) |

| Freshwater shrimp | Enrofloxacin (62.50%), cadmium (14.29%), furazolidone metabolites (9.82%), nitrofurazone metabolites (7.14%) |

| Seawater fish | Enrofloxacin (40.49%), furazolidone metabolites (16.20%), total volatile basic nitrogen (9.86%), chloramphenicol (7.75%), malachite green (7.39%), sulfonamides (total) (5.63%) |

| Freshwater crab | Cadmium (71.43%), nitrofurazone metabolites (14.29%), furazolidone metabolites (14.29%). |

| Risk Substance | Moran’s I | Z Value | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cadmium | 0.312 | 2.918 | 0.002 |

| Enrofloxacin | 0.386 | 3.538 | 0.000 |

| Total volatile basic nitrogen | −0.155 | −1.024 | 0.153 |

| Sulfur dioxide | −0.124 | −0.762 | 0.223 |

| Diazepam | 0.141 | 1.473 | 0.07 |

| Malachite green | 0.084 | 0.986 | 0.162 |

| Furazolidone metabolites | 0.319 | 2.971 | 0.001 |

| Chloramphenicol | 0.331 | 3.076 | 0.001 |

| Nitrofurazone metabolites | 0.108 | 1.191 | 0.117 |

| Sodium pentachlorophenate | −0.04 | −0.054 | 0.479 |

| Metronidazole | 0.002 | 0.301 | 0.382 |

| Ofloxacin | 0.229 | 2.212 | 0.013 |

| Region | Cadmium | Enrofloxacin | Furazolidone Metabolites | Chloramphenicol | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local Moran’s I | p Value | Local Moran’s I | p Value | Local Moran’s I | p Value | Local Moran’s I | p Value | |

| Beijing | 0.168 | 0.003 | 0.476 | 0.058 | 0.115 | 0.113 | 0.068 | 0.184 |

| Tianjin | 0.282 | 0.003 | 0.596 | 0.078 | 0.174 | 0.161 | 0.064 | 0.179 |

| Hebei | 0.895 | 0.046 | 0.534 | 0.011 | 0.136 | 0.022 | 0.046 | 0.136 |

| Shanxi | −0.687 | 0.024 | 0.234 | 0.048 | 0.168 | 0.114 | 0.198 | 0.081 |

| Inner Mongolia | 0.463 | 0.019 | 0.494 | 0.009 | 0.367 | 0.023 | 0.152 | 0.089 |

| Liaoning | 2.672 | 0.000 | 0.494 | 0.041 | 0.408 | 0.069 | −0.296 | 0.113 |

| Jilin | 1.594 | 0.026 | 0.546 | 0.053 | 0.524 | 0.042 | 0.042 | 0.205 |

| Heilongjiang | 0.142 | 0.002 | 0.529 | 0.064 | 0.524 | 0.071 | 0.246 | 0.105 |

| Shanghai | 0.031 | 0.22 | 0.468 | 0.008 | 0.211 | 0.009 | 0.098 | 0.171 |

| Jiangsu | −0.061 | 0.146 | 0.417 | 0.032 | −0.055 | 0.046 | 0.124 | 0.086 |

| Zhejiang | −0.179 | 0.133 | 2.282 | 0.002 | 0.879 | 0.034 | 0.036 | 0.101 |

| Anhui | −0.035 | 0.202 | 0.73 | 0.004 | −0.185 | 0.103 | 0.123 | 0.097 |

| Fujian | 0.149 | 0.069 | 0.04 | 0.001 | 3.39 | 0.000 | 0.099 | 0.053 |

| Jiangxi | −0.17 | 0.199 | 1.659 | 0.004 | −0.466 | 0.001 | −0.068 | 0.128 |

| Shandong | 0.258 | 0.026 | −0.007 | 0.234 | 0.223 | 0.115 | 0.116 | 0.074 |

| Henan | −0.014 | 0.154 | 0.107 | 0.148 | 0.126 | 0.058 | 0.129 | 0.064 |

| Hubei | 0.031 | 0.196 | 0.369 | 0.005 | 0.023 | 0.223 | −0.018 | 0.055 |

| Hunan | 0.005 | 0.168 | 0.057 | 0.008 | −0.095 | 0.058 | −0.43 | 0.001 |

| Guangdong | 0.042 | 0.243 | −0.153 | 0.072 | 0.847 | 0.015 | 2.42 | 0.000 |

| Guangxi | 0.141 | 0.131 | −0.013 | 0.25 | 0.065 | 0.201 | 0.91 | 0.07 |

| Hainan | −0.526 | 0.08 | 0.083 | 0.176 | 1.364 | 0.026 | 5.168 | 0.005 |

| Chongqing | 0.455 | 0.024 | 0.388 | 0.138 | −0.099 | 0.249 | 0.011 | 0.112 |

| Sichuan | 0.561 | 0.007 | 0.12 | 0.155 | −0.028 | 0.213 | −0.005 | 0.047 |

| Guizhou | 0.419 | 0.017 | −0.06 | 0.029 | −0.01 | 0.099 | −0.309 | 0.033 |

| Yunnan | 0.599 | 0.016 | −0.002 | 0.241 | −0.044 | 0.22 | −0.16 | 0.032 |

| Tibet | 0.597 | 0.017 | −0.008 | 0.249 | 0.208 | 0.141 | 0.149 | 0.114 |

| Shaanxi | 0.254 | 0.032 | −0.011 | 0.221 | −0.002 | 0.174 | 0.146 | 0.068 |

| Gansu | 0.251 | 0.047 | 0.254 | 0.062 | 0.131 | 0.099 | 0.204 | 0.052 |

| Qinghai | 0.491 | 0.02 | 0.098 | 0.162 | 0.118 | 0.133 | 0.183 | 0.092 |

| Ningxia | 0.07 | 0.197 | 0.579 | 0.067 | 0.266 | 0.143 | 0.246 | 0.091 |

| Xinjiang | 0.479 | 0.041 | 0.275 | 0.093 | 0.278 | 0.11 | 0.246 | 0.091 |

| Region | Month | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | June | July | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

| Shanghai | 0.765 | 0.764 | 0.777 | 0.790 | 0.823 | 0.809 | 0.819 | 0.845 | 0.871 | 0.887 | 0.891 | 0.798 |

| Henan | 0.736 | 0.735 | 0.747 | 0.760 | 0.792 | 0.778 | 0.787 | 0.813 | 0.838 | 0.853 | 0.858 | 0.768 |

| Beijing | 0.753 | 0.752 | 0.765 | 0.778 | 0.811 | 0.797 | 0.806 | 0.832 | 0.858 | 0.873 | 0.878 | 0.786 |

| Shandong | 0.737 | 0.737 | 0.749 | 0.762 | 0.794 | 0.780 | 0.789 | 0.814 | 0.840 | 0.855 | 0.859 | 0.769 |

| Jiangsu | 0.751 | 0.750 | 0.763 | 0.776 | 0.808 | 0.794 | 0.803 | 0.829 | 0.855 | 0.870 | 0.875 | 0.783 |

| Jilin | 0.763 | 0.762 | 0.775 | 0.788 | 0.821 | 0.807 | 0.816 | 0.843 | 0.869 | 0.884 | 0.889 | 0.796 |

| Hunan | 0.736 | 0.736 | 0.748 | 0.761 | 0.793 | 0.779 | 0.788 | 0.813 | 0.839 | 0.854 | 0.858 | 0.768 |

| Guangxi | 0.736 | 0.736 | 0.748 | 0.761 | 0.793 | 0.779 | 0.788 | 0.813 | 0.839 | 0.854 | 0.858 | 0.769 |

| Guangdong | 0.749 | 0.749 | 0.761 | 0.774 | 0.807 | 0.793 | 0.802 | 0.828 | 0.854 | 0.869 | 0.873 | 0.782 |

| Zhejiang | 0.790 | 0.789 | 0.802 | 0.816 | 0.850 | 0.836 | 0.845 | 0.872 | 0.900 | 0.916 | 0.921 | 0.824 |

| Hainan | 0.737 | 0.736 | 0.748 | 0.761 | 0.793 | 0.780 | 0.788 | 0.814 | 0.839 | 0.854 | 0.859 | 0.769 |

| Fujian | 0.746 | 0.746 | 0.758 | 0.771 | 0.804 | 0.790 | 0.799 | 0.824 | 0.850 | 0.865 | 0.870 | 0.779 |

| Guizhou | 0.729 | 0.728 | 0.740 | 0.753 | 0.785 | 0.771 | 0.780 | 0.805 | 0.830 | 0.845 | 0.849 | 0.760 |

| Jiangxi | 0.770 | 0.769 | 0.782 | 0.796 | 0.829 | 0.815 | 0.824 | 0.850 | 0.877 | 0.893 | 0.897 | 0.803 |

| Heilongjiang | 0.724 | 0.724 | 0.736 | 0.749 | 0.780 | 0.767 | 0.775 | 0.800 | 0.825 | 0.840 | 0.844 | 0.756 |

| Sichuan | 0.740 | 0.740 | 0.752 | 0.765 | 0.797 | 0.783 | 0.792 | 0.818 | 0.843 | 0.858 | 0.863 | 0.773 |

| Chongqing | 0.766 | 0.765 | 0.778 | 0.792 | 0.825 | 0.811 | 0.820 | 0.846 | 0.873 | 0.888 | 0.893 | 0.800 |

| Anhui | 0.735 | 0.734 | 0.747 | 0.760 | 0.791 | 0.778 | 0.787 | 0.812 | 0.837 | 0.852 | 0.857 | 0.767 |

| Liaoning | 0.732 | 0.731 | 0.744 | 0.757 | 0.788 | 0.775 | 0.783 | 0.808 | 0.834 | 0.849 | 0.853 | 0.764 |

| Tianjin | 0.723 | 0.722 | 0.734 | 0.747 | 0.778 | 0.765 | 0.773 | 0.798 | 0.823 | 0.838 | 0.842 | 0.754 |

| Hubei | 0.727 | 0.726 | 0.738 | 0.751 | 0.783 | 0.769 | 0.778 | 0.803 | 0.828 | 0.843 | 0.847 | 0.759 |

| Yunnan | 0.729 | 0.729 | 0.741 | 0.754 | 0.785 | 0.772 | 0.780 | 0.805 | 0.831 | 0.845 | 0.850 | 0.761 |

| Hebei | 0.737 | 0.736 | 0.748 | 0.761 | 0.793 | 0.779 | 0.788 | 0.814 | 0.839 | 0.854 | 0.859 | 0.769 |

| Shanxi | 0.719 | 0.718 | 0.730 | 0.743 | 0.774 | 0.761 | 0.769 | 0.794 | 0.819 | 0.833 | 0.838 | 0.750 |

| Ningxia | 0.716 | 0.715 | 0.727 | 0.740 | 0.771 | 0.757 | 0.766 | 0.791 | 0.815 | 0.830 | 0.834 | 0.747 |

| Shaanxi | 0.726 | 0.725 | 0.737 | 0.750 | 0.781 | 0.768 | 0.777 | 0.802 | 0.827 | 0.841 | 0.846 | 0.757 |

| Inner Mongolia | 0.720 | 0.719 | 0.731 | 0.744 | 0.775 | 0.762 | 0.771 | 0.795 | 0.820 | 0.835 | 0.839 | 0.751 |

| Gansu | 0.717 | 0.716 | 0.728 | 0.741 | 0.772 | 0.758 | 0.767 | 0.791 | 0.816 | 0.831 | 0.835 | 0.748 |

| Qinghai | 0.717 | 0.716 | 0.728 | 0.741 | 0.772 | 0.759 | 0.767 | 0.792 | 0.817 | 0.831 | 0.836 | 0.748 |

| Tibet | 0.715 | 0.714 | 0.726 | 0.739 | 0.769 | 0.756 | 0.765 | 0.789 | 0.814 | 0.829 | 0.833 | 0.746 |

| Xinjiang | 0.720 | 0.719 | 0.731 | 0.744 | 0.775 | 0.762 | 0.771 | 0.795 | 0.820 | 0.835 | 0.839 | 0.751 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tao, G.; Li, G.; Pu, D.; Bao, L.; Xu, S.; Yang, H.; Hu, K. Spatiotemporal Patterns of Aquatic Product Risks in China Based on Entropy-Weighted TOPSIS. Foods 2025, 14, 4263. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244263

Tao G, Li G, Pu D, Bao L, Xu S, Yang H, Hu K. Spatiotemporal Patterns of Aquatic Product Risks in China Based on Entropy-Weighted TOPSIS. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4263. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244263

Chicago/Turabian StyleTao, Guangcan, Guoyan Li, Dingfang Pu, Luolin Bao, Su Xu, Hongbo Yang, and Kang Hu. 2025. "Spatiotemporal Patterns of Aquatic Product Risks in China Based on Entropy-Weighted TOPSIS" Foods 14, no. 24: 4263. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244263

APA StyleTao, G., Li, G., Pu, D., Bao, L., Xu, S., Yang, H., & Hu, K. (2025). Spatiotemporal Patterns of Aquatic Product Risks in China Based on Entropy-Weighted TOPSIS. Foods, 14(24), 4263. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244263