Effects of Glucose Tablet Candy Ingestion on Attention Following Smartphone Use in Healthy Adults: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Crossover Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

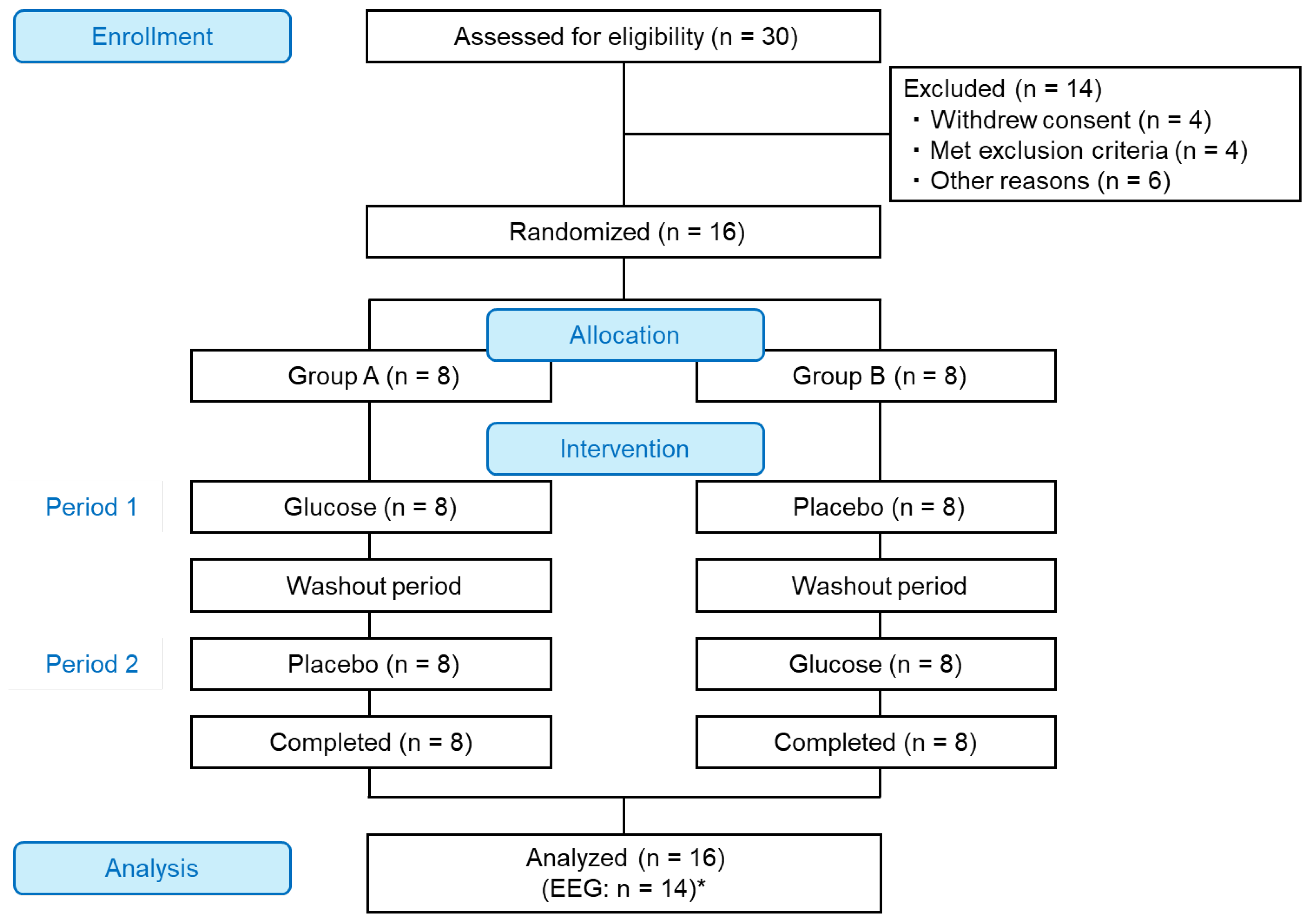

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Test Product

2.3. Study Procedure

2.3.1. Screening and Familiarization

2.3.2. Intervention Procedures

2.4. Efficacy Assessment Measures

2.4.1. Primary Outcome: Attention Test

2.4.2. EEG

2.4.3. VAS

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Attention Test

3.3. EEG

3.4. VAS

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SNS | Social networks |

| EEG | Electroencephalography |

| SMR | Sensorimotor rhythm |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| SBP | Systolic blood pressure |

| DBP | Diastolic blood pressure |

| UMIN | University Hospital Medical Information Network |

| VAS | Visual analog scale |

| ST | Stroop test |

| SAT | Shifting attention test |

| CPT | Continuous performance test |

| FPCPT | Four-part continuous performance test |

| ChZ | Mid-prefrontal electrode |

| ChR | Right prefrontal electrode |

| ChL | Left prefrontal electrode |

References

- FY2023 Survey Report on Usage Time of Information and Communications Media and Information Behavior. Available online: https://www.soumu.go.jp/main_sosiki/joho_tsusin/eng/pressrelease/2024/pdf/000382186_20240621_4.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Amez, S.; Baert, S. Smartphone use and academic performance: A literature review. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 103, 101618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunday, O.J.; Adesope, O.O.; Maarhuis, P.L. The effects of smartphone addiction on learning: A meta-analysis. Compt. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2021, 4, 100114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, H.; Taki, Y.; Asano, K.; Asano, M.; Sassa, Y.; Yokota, S.; Kotozaki, Y.; Nouchi, R.; Kawashima, R. Impact of frequency of internet use on development of brain structures and verbal intelligence: Longitudinal analyses. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2018, 39, 4471–4479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, M.; Chen, X.; Zhao, Q.; Zhou, Z. Attentional scope is reduced by Internet use: A behavior and ERP study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0198543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswald, T.K.; Kohler, M.; Rumbold, A.R.; Kedzior, S.G.E.; Moore, V.M. The acute psychological effects of screen time and the restorative potential of nature immersion amongst adolescents: A randomised pre-post pilot study. J. Environ. Psychol. 2023, 92, 102183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquet, T.; Lepers, R.; Pageaux, B.; Poulin-Charronnat, B. Acute smartphone use impairs vigilance and inhibition capacities. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 23046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortes, L.S.; De Lima-Junior, D.; Fiorese, L.; Nascimento-Júnior, J.R.A.; Mortatti, A.L.; Ferreira, M.E.C. The effect of smartphones and playing video games on decision-making in soccer players: A crossover and randomised study. J. Sports Sci. 2020, 38, 552–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, R.; White, D.; Cleeland, C.; Scholey, A. Fuel for Thought? A Systematic Review of Neuroimaging Studies into Glucose Enhancement of Cognitive Performance. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2020, 30, 234–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, N.B.; Lawton, C.L.; Dye, L. The Effects of Carbohydrates, in Isolation and Combined with Caffeine, on Cognitive Performance and Mood—Current Evidence and Future Directions. Nutrients 2018, 10, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sünram-Lea, S.I.; Owen, L. The impact of diet-based glycaemic response and glucose regulation on cognition: Evidence across the lifespan. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2017, 76, 466–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.A.; Riby, L.M.; Eekelen, J.A.M.v.; Foster, J.K. Glucose enhancement of human memory: A comprehensive research review of the glucose memory facilitation effect. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2011, 35, 770–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inagaki, H.; Yamamoto, T.; Shimotsuma, S.; Mori, S.; Morita, M.; Itoh, M.; Takashi, M. Positive effects of Glucose ingestion on working memory capacity and attention in healthy volunteers: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled cross-over comparison study. Jpn. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 48, 599–609. [Google Scholar]

- Setoguchi, Y.; Nishida, R.; Shigaki, T.; Yoshihara, M.; Inagaki, H.; Matsui, Y.; Mato, T.; Sato, H. Effects of glucose-containing Ramune (tablet candy) on brain activity and psychological status during cognitive tasks in healthy young adults: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover comparison study. Jpn. Pharmacol. Ther. 2024, 52, 711–722. [Google Scholar]

- Furukado, R.; Hagiwara, G.; Inagaki, H. Effects of glucose Ramune candy ingestion on concentration during esports play and cognitive function. J. Digit. Life 2022, 2, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagiwara, G.; Kawahara, I.; Kihara, S. An attempt to verify the positive effects of esports_ Focusing on concentration and cognitive skill. J. Digit. Life 2021, 1, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Marzbani, H.; Marateb, H.R.; Mansourian, M. Neurofeedback: A comprehensive review on system design, methodology and clinical applications. Basic Clin. Neurosci. 2016, 7, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaer, R.; Eldin, S.N.; Gashri, C.; Horowitz-Kraus, T. Decreased frontal theta frequency during the presence of smartphone among children: An EEG study. Pediat. Res. 2024, 96, 1699–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, R.; Canuet, L.; Ishihara, T.; Aoki, Y.; Ikeda, S.; Hata, M.; Katsimichas, T.; Gunji, A.; Takahashi, H.; Nakahachi, T.; et al. Frontal midline theta rhythm and gamma power changes during focused attention on mental calculation: An MEG beamformer analysis. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualtieri, C.T.; Johnson, L.G. Reliability and validity of a computerized neurocognitive test battery, CNS vital signs. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2006, 21, 623–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Li, R.; Zhang, J. A review of visual sustained attention: Neural mechanisms and computational models. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Yeo, M.; Yoon, G. Comparison between concentration and immersion based on EEG analysis. Sensors 2019, 19, 1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langner, R.; Eickhoff, S.B. Sustaining attention to simple tasks: A meta-analytic review of the neural mechanisms of vigilant attention. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 139, 870–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 28.6 ± 7.1 |

| Sex (female/male) | 8/8 |

| Height (cm) | 165.8 ± 9.7 |

| Body weight (kg) | 57.0 ± 9.6 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.1 ± 2.8 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 110.8 ± 14.3 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 66.5 ± 12.6 |

| Task | Test | Standardized Scores | p-Values | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 16) | Glucose (n = 16) | Product | Period | Sequence | ||||

| ST | Simple reaction time | Pre | 97.9 ± 4.5 | 93.8 ± 1.9 | ||||

| Post | 92.6 ± 2.6 | 94.2 ± 2.1 | 0.263 | 0.042 * | 0.134 | |||

| Complex reaction time | Pre | 97.7 ± 3.0 | 98.8 ± 2.4 | |||||

| Post | 97.9 ± 2.8 | 100.0 ± 2.1 | 0.224 | 0.003 * | 0.625 | |||

| Stroop reaction time | Pre | 102.1 ± 3.1 | 104.1 ± 3.0 | |||||

| Post | 104.9 ± 2.3 | 106.2 ± 1.5 | 0.456 | 0.057 | 0.265 | |||

| Stroop commission errors | Pre | 94.6 ± 3.0 | 93.0 ± 4.8 | |||||

| Post | 89.2 ± 3.4 | 88.1 ± 5.4 | 0.788 | 0.025 * | 0.459 | |||

| SAT | Correct responses | Pre | 108.9 ± 3.0 | 109.1 ± 2.4 | ||||

| Post | 112.3 ± 3.3 | 111.4 ± 3.2 | 0.732 | 0.018 * | 0.402 | |||

| Errors | Pre | 106.8 ± 2.0 | 106.7 ± 1.7 | |||||

| Post | 104.1 ± 2.5 | 103.8 ± 2.7 | 0.926 | 0.926 | 0.282 | |||

| Correct reaction time | Pre | 116.6 ± 2.6 | 117.0 ± 2.6 | |||||

| Post | 121.2 ± 2.6 | 119.7 ± 2.4 | 0.488 | 0.004 * | 0.954 | |||

| CPT | Correct responses | Pre | 100.3 ± 3.8 | 102.8 ± 1.3 | ||||

| Post | 102.1 ± 1.9 | 100.9 ± 2.2 | 0.660 | 0.660 | 0.087 | |||

| Omission errors | Pre | 100.3 ± 3.8 | 102.8 ± 1.3 | |||||

| Post | 102.1 ± 1.9 | 100.9 ± 2.2 | 0.660 | 0.660 | 0.087 | |||

| Commission errors | Pre | 99.6 ± 3.8 | 99.0 ± 2.9 | |||||

| Post | 104.4 ± 1.7 | 104.6 ± 2.0 | 0.959 | 0.316 | 0.250 | |||

| Reaction time | Pre | 93.2 ± 2.8 | 94.2 ± 2.2 | |||||

| Post | 90.5 ± 2.8 | 92.4 ± 2.9 | 0.349 | 0.415 | 0.063 | |||

| FPCPT1 | Average correct response time | Pre | 102.3 ± 2.0 | 102.8 ± 1.9 | ||||

| Post | 104.5 ± 1.4 | 100.8 ± 2.9 | 0.123 | 0.830 | 0.108 | |||

| FPCPT2 | Correct responses | Pre | 102.5 ± 0.1 | 102.5 ± 0.1 | ||||

| Post | 100.8 ± 1.7 | 102.5 ± 0.1 | 0.319 | 0.319 | 0.319 | |||

| Average correct response time | Pre | 96.9 ± 1.7 | 99.7 ± 3.8 | |||||

| Post | 95.6 ± 1.9 | 100.2 ± 1.5 | 0.039 * | 0.878 | 0.584 | |||

| Incorrect responses | Pre | 101.6 ± 2.2 | 95.8 ± 7.7 | |||||

| Post | 97.4 ± 4.2 | 99.3 ± 4.3 | 0.028 * | 0.565 | 0.353 | |||

| Omission errors | Pre | 102.5 ± 0.1 | 102.5 ± 0.1 | |||||

| Post | 100.8 ± 1.7 | 102.5 ± 0.1 | 0.319 | 0.319 | 0.319 | |||

| FPCPT3 | Correct responses | Pre | 109.1 ± 1.9 | 111.7 ± 0.8 | ||||

| Post | 111.7 ± 1.0 | 110.8 ± 1.1 | 0.179 | 1.000 | 0.196 | |||

| Average correct response time | Pre | 106.0 ± 2.5 | 106.7 ± 1.9 | |||||

| Post | 108.2 ± 2.0 | 109.3 ± 1.8 | 0.540 | 0.243 | 0.189 | |||

| Incorrect responses | Pre | 102.7 ± 0.5 | 101.8 ± 1.0 | |||||

| Post | 102.1 ± 0.6 | 102.4 ± 0.6 | 0.670 | 0.570 | 0.370 | |||

| Omission errors | Pre | 109.1 ± 1.9 | 111.7 ± 0.8 | |||||

| Post | 111.7 ± 1.0 | 110.8 ± 1.1 | 0.179 | 1.000 | 0.196 | |||

| FPCPT4 | Correct responses | Pre | 112.5 ± 1.5 | 109.0 ± 2.5 | ||||

| Post | 114.3 ± 1.1 | 112.4 ± 2.2 | 0.384 | 0.681 | 0.505 | |||

| Average correct response time | Pre | 105.9 ± 1.8 | 108.8 ± 1.8 | |||||

| Post | 109.3 ± 2.0 | 110.0 ± 1.3 | 0.757 | 0.451 | 0.738 | |||

| Incorrect responses | Pre | 104.8 ± 1.9 | 106.9 ± 1.6 | |||||

| Post | 106.8 ± 1.3 | 100.9 ± 4.7 | 0.237 | 0.700 | 0.594 | |||

| Omission errors | Pre | 112.5 ± 1.5 | 109.0 ± 2.5 | |||||

| Post | 114.3 ± 1.1 | 112.4 ± 2.2 | 0.384 | 0.681 | 0.505 | |||

| Item | Status | VAS (cm) | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 16) | Glucose (n = 16) | Product | Period | Sequence | ||

| Concentration | Post-load | 3.8 ± 0.5 | 3.0 ± 0.5 | |||

| Post-test | 3.8 ± 0.6 | 3.2 ± 0.6 | 0.172 | 0.280 | 0.562 | |

| Physical fatigue | Post-load | 4.2 ± 0.4 | 3.7 ± 0.5 | |||

| Post-test | 4.1 ± 0.6 | 2.9 ± 0.5 | 0.029 * | 0.219 | 0.403 | |

| Mental fatigue | Post-load | 4.5 ± 0.4 | 4.3 ± 0.5 | |||

| Post-test | 4.2 ± 0.6 | 3.3 ± 0.5 | 0.158 | 0.754 | 0.185 | |

| Mental clarity (Clear-headedness) | Post-load | 4.5 ± 0.4 | 3.5 ± 0.5 | |||

| Post-test | 4.2 ± 0.6 | 3.1 ± 0.5 | 0.039 * | 0.212 | 0.454 | |

| Motivation | Post-load | 4.1 ± 0.5 | 3.0 ± 0.4 | |||

| Post-test | 3.5 ± 0.5 | 3.2 ± 0.5 | 0.320 | 0.932 | 0.682 | |

| Sleepiness | Post-load | 2.9 ± 0.4 | 2.6 ± 0.5 | |||

| Post-test | 3.0 ± 0.5 | 2.2 ± 0.4 | 0.108 | 0.386 | 0.357 | |

| Item | Status | VAS (cm) | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 32) | Time Points | Period | Sequence | ||

| Concentration | At arrival | 3.5 ± 0.3 | |||

| Pre-load | 4.5 ± 0.3 | 0.008 * | 0.118 | 0.962 | |

| Post-load | 3.4 ± 0.4 | 0.010 * | 0.224 | 0.462 | |

| Physical fatigue | At arrival | 2.6 ± 0.3 | |||

| Pre-load | 4.0 ± 0.3 | 0.000 * | 0.052 | 0.613 | |

| Post-load | 4.0 ± 0.3 | 0.949 | 0.326 | 0.920 | |

| Mental fatigue | At arrival | 2.7 ± 0.3 | |||

| Pre-load | 4.4 ± 0.3 | 0.000 * | 0.250 | 0.781 | |

| Post-load | 4.4 ± 0.3 | 0.978 | 0.859 | 0.476 | |

| Mental clarity (Clear-headedness) | At arrival | 3.6 ± 0.3 | |||

| Pre-load | 4.8 ± 0.3 | 0.003 * | 0.388 | 0.645 | |

| Post-load | 4.0 ± 0.3 | 0.043 * | 0.068 | 0.865 | |

| Motivation | At arrival | 3.2 ± 0.3 | |||

| Pre-load | 4.0 ± 0.3 | 0.050 * | 0.550 | 0.269 | |

| Post-load | 3.6 ± 0.3 | 0.292 | 0.827 | 0.528 | |

| Sleepiness | At arrival | 3.6 ± 0.4 | |||

| Pre-load | 4.0 ± 0.4 | 0.361 | 0.302 | 0.182 | |

| Post-load | 2.7 ± 0.3 | 0.003 * | 0.027 * | 0.722 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Setoguchi, Y.; Tsukiashi, M.; Maruki-Uchida, H.; Iemoto, N.; Ebihara, S.; Mato, T. Effects of Glucose Tablet Candy Ingestion on Attention Following Smartphone Use in Healthy Adults: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Crossover Trial. Foods 2025, 14, 4233. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244233

Setoguchi Y, Tsukiashi M, Maruki-Uchida H, Iemoto N, Ebihara S, Mato T. Effects of Glucose Tablet Candy Ingestion on Attention Following Smartphone Use in Healthy Adults: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Crossover Trial. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4233. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244233

Chicago/Turabian StyleSetoguchi, Yuko, Motoki Tsukiashi, Hiroko Maruki-Uchida, Naoki Iemoto, Shukuko Ebihara, and Takashi Mato. 2025. "Effects of Glucose Tablet Candy Ingestion on Attention Following Smartphone Use in Healthy Adults: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Crossover Trial" Foods 14, no. 24: 4233. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244233

APA StyleSetoguchi, Y., Tsukiashi, M., Maruki-Uchida, H., Iemoto, N., Ebihara, S., & Mato, T. (2025). Effects of Glucose Tablet Candy Ingestion on Attention Following Smartphone Use in Healthy Adults: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Crossover Trial. Foods, 14(24), 4233. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244233