Using Volatile Oxidation Products to Predict the Inflammatory Capacity of Oxidized Methyl Linoleate

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

2.2. Preparation of Oxidized MLO Samples Under Different Temperatures

2.3. Free Radical Analysis

2.4. Analysis of Volatile Compounds

2.5. Analysis of Lipophilic Aldehydes

2.6. Preparation of Oxidized MLO Emulsions

2.7. Cell Culture

2.8. Determination of Cell Viability

2.9. Measurement of Inflammatory Factors at Gene and Protein Expression Levels

2.10. Determination of Oxidative Stress-Related Indicators

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Changes in Free Radicals During MLO Oxidation

3.2. Changes in Volatile Compounds During MLO Oxidation

3.3. Changes in Lipophilic Aldehydes During MLO Oxidation

3.4. Effects of Oxidized MLO on Inflammatory Factor Gene Expression

3.5. Effects of Oxidized MLO on Inflammatory Factor Protein Expression

3.6. Effects of Oxidized MLO on Oxidative Stress—Related Parameters in RAW264.7 Cells

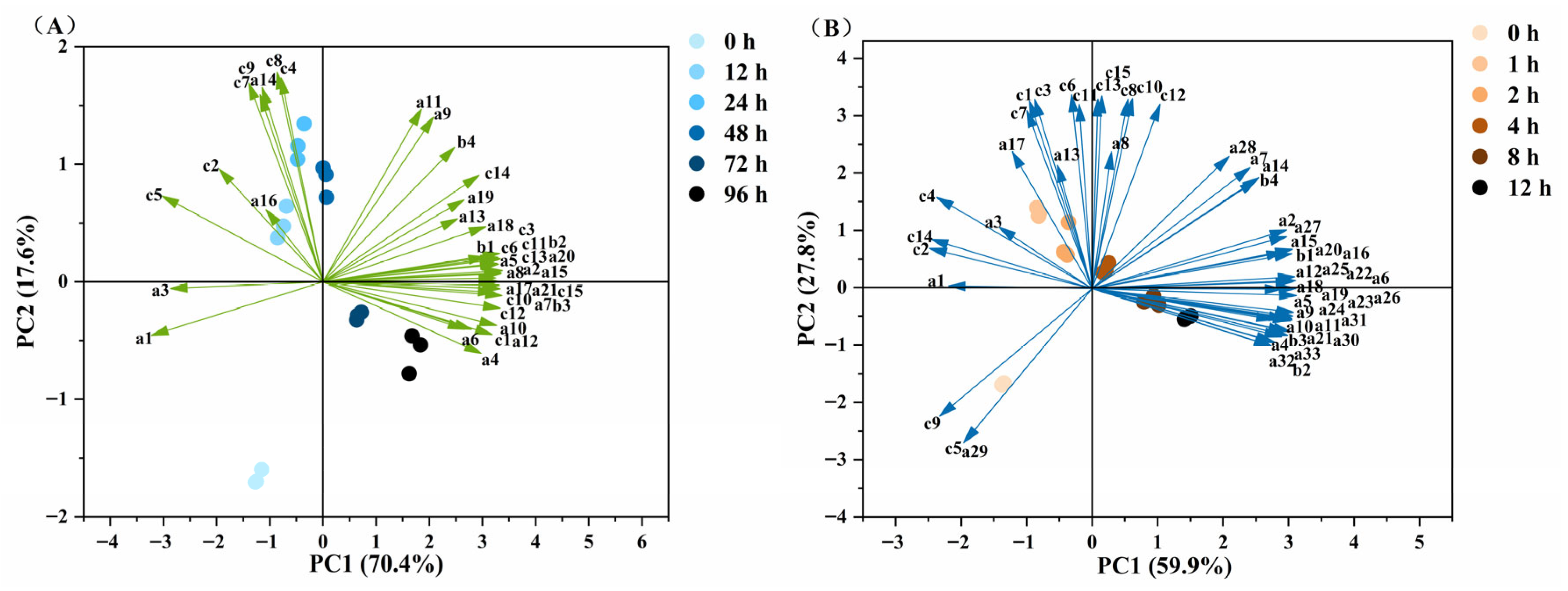

3.7. OPLS-DA Analysis of MLO Oxidation Products

3.8. Correlation Analysis of MLO Oxidation Products

3.9. Analysis of Pro-Inflammatory Predictive Models for Oxidized MLO

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, C.; Hong, B.; Jiang, S.; Luo, X.; Lin, H.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, J.; Yue, X.; Shi, H.; Wu, R. Recent advances on essential fatty acid biosynthesis and production: Clarifying the roles of Δ12/Δ15 fatty acid desaturase. Biochem. Eng. J. 2022, 178, 108306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Liu, X.; Xu, X.; Wang, S.; Yang, J.; Zou, Y.; Ma, D.; Zhang, J.; Liang, L.; Wen, C.; et al. Key to Promoting Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons Generation in Lipid Thermal Reactions: Free Radicals Originating from Lipid Hydroperoxides. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 17176–17189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Sarkhel, S.; Roy, A.; Mohan, A. Interrelationship of lipid aldehydes (MDA, 4-HNE, and 4-ONE) mediated protein oxidation in muscle foods. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 11809–11825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhoussaine, O.; El Kourchi, C.; Harhar, H.; El Moudden, H.; El Yadini, A.; Ullah, R.; Iqbal, Z.; Goh, K.W.; Goh, B.H.; Bouyahya, A.; et al. Phytochemical characterization and nutritional value of vegetable oils from ripe berries of Schinus terebinthifolia raddi and Schinus molle L., through extraction methods. Food Chem. X 2024, 23, 101580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsavova, J.; Misurcova, L.; Vavra Ambrozova, J.; Vicha, R.; Mlcek, J. Fatty Acids Composition of Vegetable Oils and Its Contribution to Dietary Energy Intake and Dependence of Cardiovascular Mortality on Dietary Intake of Fatty Acids. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 12871–12890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M.F.; Kitamura, F.; Han, Y.; Du, H.; McClements, D.J.; Xiao, H. Adverse effects of linoleic acid: Influence of lipid oxidation on lymphatic transport of citrus flavonoid and enterocyte morphology. Food Chem. 2022, 369, 130968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhoosh, R.; Nyström, L. Antioxidant potency of gallic acid, methyl gallate and their combinations in sunflower oil triacylglycerols at high temperature. Food Chem. 2018, 244, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xing, C.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Sun, W.; Xie, D.; Xu, G.; Wang, X. Validity of total polar compound and its three components in monitoring the evolution of epoxy fatty acids in frying oil: Fast food restaurant conditions. Food Chem. 2023, 405, 134945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, J.W.; Cheng, Y.J.; Liu, Y.F. Volatile components of deep-fried soybean oil as indicator indices of lipid oxidation and quality degradation. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2020, 246, 1183–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, Y. Effects of epoxy stearic acid on lipid metabolism in HepG2 cells. J. Food 2020, 85, 3644–3652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, B.-N.; Zhang, J.-J.; Xu, X.; Li, C.; Shu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, X.; Shen, Y. Characterization and metabolism pathway of volatile compounds in walnut oil obtained from various ripening stages via HS-GC-IMS and HS-SPME-GC–MS. Food Chem. 2024, 435, 137547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitts, D.D.; Singh, A.; Fathordoobady, F.; Doi, B.; Singh, A.P. Plant Extracts Inhibit the Formation of Hydroperoxides and Help Maintain Vitamin E Levels and Omega-3 Fatty Acids During High Temperature Processing and Storage of Hempseed and Soybean Oils. J. Food Sci. 2019, 84, 3147–3155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzocchi, A.; De Cosmi, V.; Risé, P.; Milani, G.P.; Turolo, S.; Syrén, M.L.; Sala, A.; Agostoni, C. Bioactive compounds in edible oils and their role in oxidative stress and inflammation. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 659551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Zhang, J.; He, L.; Xing, R.; Yu, N.; Chen, Y. New insight into the evolution of volatile profiles in four vegetable oils with different saturations during thermal processing by integrated volatolomics and lipidomics analysis. Food Chem. 2023, 403, 134342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, W.; Jiao, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Song, J.; Wu, H.; Xiao, J. Correlation between volatile oxidation products and inflammatory markers in docosahexaenoic acid: Insights from OPLS-DA and predictive modeling. Food Biosci. 2025, 63, 105756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Fan, W.; Chu, F.; Wang, C.; Pei, D. Identification of Volatile Oxidation Compounds as Potential Markers of Walnut Oil Quality. J. Food Sci. 2018, 83, 2745–2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezende, L.G.; Tasso, T.T.; Candido, P.H.S.; Baptista, M.S. Assessing Photosensitized Membrane Damage: Available Tools and Comprehensive Mechanism. Photochem. Photobiol. 2022, 98, 572–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.J.; Wang, Y.; Cao, P.R.; Liu, Y. Thermal Oxidation Rate of Oleic Acid Increased Dramatically at 140 °C Studied using Electron Spin Resonance and GC-MS/MS. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2019, 96, 937–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, Z.; Hu, Y.; Wu, X.; Wu, C.; Xiong, Z. Characteristic volatile compounds of white tea with different storage times using E-nose, HS–GC–IMS, and HS–SPME–GC–MS. J. Food Sci. 2024, 89, 9137–9153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Wang, G.; Xiong, L.; Yang, Z.; Ma, Y.; Qi, Y.; Li, Y. Characterization of volatile organic compounds in walnut oil with various oxidation levels using olfactory analysis and HS-SPME-GC/MS. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2024, 9, 100848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevolleau, S.; Noguer-Meireles, M.-H.; Mervant, L.; Martin, J.-F.; Jouanin, I.; Pierre, F.; Naud, N.; Guéraud, F.; Debrauwer, L. Towards Aldehydomics: Untargeted Trapping and Analysis of Reactive Diet-Related Carbonyl Compounds Formed in the Intestinal Lumen. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreoli, R.; Manini, P.; Corradi, M.; Mutti, A.; Niessen, W.M.A. Determination of patterns of biologically relevant aldehydes in exhaled breath condensate of healthy subjects by liquid chromatography/atmospheric chemical ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2003, 17, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, X.; Fang, T.; Zheng, J.; Guo, M. Physicochemical Properties and Cellular Uptake of Astaxanthin-Loaded Emulsions. Molecules 2019, 24, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, A. Real-time or quantitative PCR. In Protocols in Advanced Genomics and Allied Techniques; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 181–209. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Li, Y.; Hu, J.; Chen, H.; Hou, X. Unveiling Radical-Based Reactions in Photochemical Vapor Generation via Online and In Situ Electron Paramagnetic Resonance Monitoring. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 18884–18895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Jia, S.; Bai, Y.; Zhou, X.; Ding, Y. Formation mechanisms of reactive carbonyl species from fatty acids in dry-cured fish during storage in the presence of free radicals. J. Futur. Foods 2021, 1, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Huang, Z.; Wang, J.; Yu, D.; Wang, L. Effect of deodorization conditions on fatty acid profile, oxidation products, and lipid-derived free radicals of soybean oil. Food Chem. 2024, 453, 139656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Song, Z.; Zhang, X.; Shi, X.; Wang, L.; Chen, Z.; Huang, J.; Wang, X. Methionine thioether reduces the content of 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal in high-temperature soybean oil by preventing the radical chain reaction. Food Chem. 2025, 471, 142811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba, F.J.; Roohinejad, S.; Ishikawa, K.; Leong, S.Y.; A Bekhit, A.E.-D.; Saraiva, J.A.; Lebovka, N. Electron spin resonance as a tool to monitor the influence of novel processing technologies on food properties. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 100, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Wang, T.; Qiang, Z.; Du, W.; Li, C. Mechanisms of the Formation of Nonvolatile and Volatile Oxidation Products from Methyl Linoleic Acid at High Temperatures. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 704–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.F.; Jiang, S.H.; Li, M.; Guo, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Qian, H.; Yao, W. Evaluation on the formation of lipid free radicals in the oxidation process of peanut oil. Lwt-Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 104, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun Xuyuan, S.X.; Liu Yuanfa, L.Y.; Li Jinwei, L.J. Analysis of thermal oxidation volatile products of four vegetable oils by HS-SPME-GC-MS. China Oils Fats 2018, 43, 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Rochat, S.; Egger, J.; Chaintreau, A. Strategy for the identification of key odorants: Application to shrimp aroma. J. Chromatogr. A 2009, 1216, 6424–6432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sérot, T.; Regost, C.; Arzel, J. Identification of odour-active compounds in muscle of brown trout (Salmo trutta) as affected by dietary lipid sources. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2002, 82, 636–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanai, T.; Hong, C. Structure-retention correlation in CGC. J. High Resolut. Chromatogr. 1989, 12, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.-S.; Chyau, C.-C.; Horng, D.-T.; Yang, J.-S. Effects of irradiation and drying on volatile components of fresh shiitake (Lentinus edodesSing). J. Sci. Food Agric. 1998, 76, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umano, K.; Hagi, Y.; Shibamoto, T. Volatile chemicals identified in extracts from newly hybrid citrus, dekopon (Shiranuhi mandarin Suppl. J.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 5355–5359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, F.; Caldeira, M.; Câmara, J. Development of a dynamic headspace solid-phase microextraction procedure coupled to GC-qMSD for evaluation the chemical profile in alcoholic beverages. Anal. Chim. Acta 2008, 609, 82–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlüter, S.; Steinhart, H.; Schwarz, F.J.; Kirchgessner, M. Changes in the odorants of boiled carp fillet (Cyprinus carpio L.) as affected by increasing methionine levels in feed. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1999, 47, 5146–5150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tressl, R.; Friese, L.; Fendesack, F.; Koeppler, H. Studies of the volatile composition of hops during storage. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1978, 26, 1426–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umano, K.; Hagi, Y.; Nakahara, K.; Shoji, A.; Shibamoto, T. Volatile constituents of green and ripened pineapple (Ananas comosus L. Merr.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 1992, 40, 599–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, T.Y.; Eiserich, J.P.; Shibamoto, T. Volatile compounds identified in headspace samples of peanut oil heated under temperatures ranging from 50 to 200 °C. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1993, 41, 1467–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadaruga, N.G.; Hadaruga, D.I.; Paunescu, V.; Tatu, C.; Ordodi, V.L.; Bandur, G. Thermal stability of the linoleic acid/α- and β-cyclodextrin complexes. Food Chem. 2006, 99, 500–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horiuchi, M.; Umano, K.; Shibamoto, T. Analysis of volatile compounds formed from fish oil heated with cysteine and trimethylamine oxide. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1998, 46, 5232–5237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallia, S.; Fernández-García, E.; Bosset, J.O. Comparison of purge and trap and solid phase microextraction techniques for studying the volatile aroma compounds of three European PDO hard cheeses. Int. Dairy J. 2005, 15, 741–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, T.; Plotto, A.; Goodner, K.; Gmitter, F.G. Distribution of aroma volatile compounds in tangerine hybrids and proposed inheritance. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2011, 91, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.H.; Kubota, K. Formation by mechanical stimulus of the flavor compounds in young leaves of Japanese pepper (Xanthoxylum piperitum DC.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 1353–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo-Bayón, M.A.; Ruíz-Rodríguez, A.; Pernin, K.; Cayot, N. Influence of eggs on the aroma composition of a sponge cake and on the aroma release in model studies on flavored sponge cakes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 1418–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chida, M.; Sone, Y.; Tamura, H. Aroma characteristics of stored tobacco cut leaves analyzed by a high vacuum distillation and canister system. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 7918–7924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umano, K.; Shibamoto, T. Analysis of headspace volatiles from overheated beef fat. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1987, 35, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.T.; Yang, Z.C.; Ding, S.F. Prediction of retention indexes. II. Structure-retention index relationship on polar columns. J. Chromatogr. 1991, 586, 85–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Guen, S.; Prost, C.; Demaimay, M. Critical comparison of three olfactometric methods for the identification of the most potent odorants in cooked mussels (Mytilus edulis). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 1307–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumitani, H.; Suekane, S.; Nakatani, A.; Tatsuka, K. Changes in composition of volatile compounds in high pressure treated peach. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1994, 42, 785–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyerstahl, P.; Marschall, H.; Weirauch, M.; Thefeld, K.; Surburg, H. Constituents of commercial Labdanum oil. Flavour Fragr. J. 1998, 13, 295–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehinagic, E.; Royer, G.; Symoneaux, R.; Jourjon, F.; Prost, C. Characterization of odor-active volatiles in apples: Influence of cultivars and maturity stage. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 2678–2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmore, J.S.; Campo, M.M.; Enser, M.; Mottram, D.S. Effect of lipid composition on meat-like model systems containing cysteine, ribose, and polyunsaturated fatty acids. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 1126–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.R.; Yu, X.Z.; Li, M.J.; Chen, J.; Wang, X. Monitoring oxidative stability and changes in key volatile compounds in edible oils during ambient storage through HS-SPME/GC-MS. Int. J. Food Prop. 2018, 20, S2926–S2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hormozi Jangi, S.R.J.C.P. Low-temperature destructive hydrodechlorination of long-chain chlorinated paraffins to diesel and gasoline range hydrocarbons over a novel low-cost reusable ZSM-5@ Al-MCM nanocatalyst: A new approach toward reuse instead of common mineralization. Chem. Pap. 2023, 77, 4963–4977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.X.; Dattmore, D.A.; Wang, W.C.; Pohnert, G.; Wolfram, S.; Zhang, J.; Yang, R.; Decker, E.A.; Lee, K.S.S.; Zhang, G. trans, trans-2,4-Decadienal, a lipid peroxidation product, induces inflammatory responses via Hsp90-or 14-3-3ζ-dependent mechanisms. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2020, 76, 108286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.-Q.; Xu, M.; Wu, H.; Raka, R.N.; Wei, M.Y.; Wang, K.Y.; Xiao, J.S. Inhibitory effect of four bioactive compounds from rosemary on lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced oxidative stress and inflammation in RAW264. 7 cells. Shipin Kexue/Food Sci. 2022, 43, 125–133. [Google Scholar]

- Tsikas, D.J.A.B. Assessment of lipid peroxidation by measuring malondialdehyde (MDA) and relatives in biological samples: Analytical and biological challenges. Anal. Biochem. 2017, 524, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiappero, J.; Cappellari, L.d.R.; Palermo, T.B.; Giordano, W.; Banchio, E. A simple method to determine antioxidant status in aromatic plants subjected to drought stress. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Educ. 2021, 49, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jomova, K.; Raptova, R.; Alomar, S.Y.; Alwasel, S.H.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Reactive oxygen species, toxicity, oxidative stress, and antioxidants: Chronic diseases and aging. Arch. Toxicol. 2023, 97, 2499–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.P.; Li, Q.R.; Yang, W.X.; Zhou, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Huang, M.; Wang, Y. Characterization of the potent odorants in Zanthoxylum armatum DC Prodr. pericarp oil by application of gas chromatography-mass spectrometry-olfactometry and odor activity value. Food Chem. 2020, 319, 126564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buslaev, P.; Mustafin, K.; Gushchin, I. Principal component analysis highlights the influence of temperature, curvature and cholesterol on conformational dynamics of lipids. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta-Biomembr. 2020, 1862, 183253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, S.A.; Zhang, G.; Decker, E.A. Biological Implications of Lipid Oxidation Products. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2017, 94, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhang, W.; Guo, Z.; Zheng, J.; Xu, P.; Zhang, X.; Yang, M.; Guan, Y.; Cheng, J.; Lu, G. Freshness Assessment of Sweetpotatoes Based on Physicochemical Properties and VOCs Using HS-GC-IMS Combined With HS-SPME-GC-MS Analyses. J. Food Biochem. 2025, 2025, 6855678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, H.; Gao, H.; Chen, H.; Fang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, W.; Han, Q. Study on the volatile oxidation compounds and quantitative prediction of oxidation parameters in walnut (Carya cathayensis Sarg.) oil. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2019, 121, 1800521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.A.; Zanella, G. Robust leave-one-out cross-validation for high-dimensional Bayesian models. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2024, 119, 2369–2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, A.; Lau, M.F.; Ng, S.P.H.; Sim, K.Y.; Chandrasekaran, S. BiCuDNNLSTM-1dCNN-A hybrid deep learning-based predictive model for stock price prediction. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 202, 117123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomares-Viciana, T.; Martínez-Valdivieso, D.; Font, R.; Gómez, P.; Del Río-Celestino, M. Characterisation and prediction of carbohydrate content in zucchini fruit using near infrared spectroscopy. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 1703–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhouchi, Z.; Botosoa, E.P.; Karoui, R. Critical assessment of formulation, processing and storage conditions on the quality of alveolar baked products determined by different analytical techniques: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 81, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | Primer Sequences | |

|---|---|---|

| β-actin | R | 5′-TCATGAAGTGTGACGTTGACATCCGT-3′ |

| F | 5′-CCTAGAAGCATTTGCGGTGCACGATG-3′ | |

| TNF-α | R | 5′-ATGAGCACAGAAAGCATGATC-3′ |

| F | 5′-TACAGGCTTGTCACTCGAATT-3′ | |

| IL-1β | R | 5′-TGCAGAGTTCCCCAACTGGTACATC-3′ |

| F | 5′-GTGCTGCCTAATGTCCCCTTGAATC-3′ | |

| COX-2 | R | 5′-AGAAGGAAATGGCTGCAGAA-3′ |

| F | 5′-GCTCGGCTTCCAGTATTGAG-3′ |

| RT | Name | CAS | Actual RI | Theoretical RI | Content (μg/g) | References | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 h | 12 h | 24 h | 48 h | 72 h | 96 h | ||||||

| 8.706 | Decane | 124-18-5 | 1060 | 1000 | 1.73 ± 0.24 | 1.24 ± 0.15 | 0.93 ± 0.06 | 0.59 ± 0.06 | 0.46 ± 0.05 | - | NIST Library |

| 9.684 | Hexanal | 66-25-1 | 1110 | 1110 | - | 7.08 ± 0.12 | 12.90 ± 0.63 | 24.20 ± 1.30 | 28.82 ± 0.77 | 46.17 ± 3.10 | [33] |

| 10.714 | Undecane | 1120-21-4 | 1164 | 1100 | 4.75 ± 0.67 | 4.13 ± 0.80 | 4.18 ± 1.00 | 3.83 ± 0.07 | 3.22 ± 0.26 | 2.45 ± 0.22 | NIST Library |

| 11.767 | 3-hydroxy Stearic Acid Methyl ester | 2420-36-2 | 1221 | 2239 | - | - | - | - | 1.75 ± 0.16 | 1.97 ± 0.42 | NIST Library |

| 14.113 | Heptenal | 18829-55-5 | 1354 | 1342 | 7.71 ± 0.35 | 22.41 ± 0.69 | 35.40 ± 1.24 | 55.74 ± 1.18 | 65.18 ± 0.84 | 89.00 ± 3.67 | [34] |

| 15.624 | Methyl octylate | 111-11-5 | 1437 | 1437 | 169.05 ± 10.01 | 170.91 ± 10.06 | 173.79 ± 2.39 | 176.10 ± 0.71 | 181.05 ± 14.93 | 228.89 ± 13.60 | [35] |

| 16.207 | (2E)-2-Octenal | 2548-87-0 | 1467 | 1467.3 | - | 3.86 ± 0.08 | 5.84 ± 0.03 | 8.51 ± 0.36 | 11.81 ± 0.47 | 23.62 ± 1.40 | [36] |

| 16.264 | Trans-2-Octen-1-ol | 18409-17-1 | 1470 | 1603 | - | 4.39 ± 0.57 | 8.03 ± 0.38 | 14.67 ± 0.86 | 19.99 ± 0.32 | 27.48 ± 1.81 | [37] |

| 17.809 | Methyl nonanoate | 1731-84-6 | 1544 | 1536 | - | 6.07 ± 0.35 | 6.51 ± 0.25 | 6.32 ± 0.07 | 6.56 ± 0.16 | 6.64 ± 0.16 | [35] |

| 18.353 | 3,5-Dimethylcyclohexanol | 5441-52-1 | 1569 | 1809 | - | - | - | 3.02 ± 0.08 | 4.11 ± 0.32 | 8.40 ± 1.00 | [38] |

| 18.576 | (2E)-2-Nonenal | 18829-56-6 | 1579 | 1574 | - | 4.20 ± 0.16 | 4.16 ± 0.16 | 4.31 ± 0.06 | 3.63 ± 0.56 | 4.31 ± 0.73 | [39] |

| 20.338 | Methyl Caprate | 110-42-9 | 1654 | 1636 | 2.73 ± 0.72 | 2.70 ± 0.28 | 3.17 ± 0.40 | 2.74 ± 0.08 | 4.55 ± 0.18 | 4.53 ± 0.74 | [35] |

| 21.471 | 4-Decenoic acid methyl ester | 1191-02-2 | 1700 | 1622 | 13.79 ± 4.21 | 16.54 ± 3.84 | 18.53 ± 2.87 | 18.88 ± 0.49 | 19.17 ± 0.83 | 22.39 ± 2.06 | [40] |

| 22.29 | 2-Butyloct-2-enal | 13019-16-4 | 1731 | 1659 | - | 0.59 ± 0.19 | 0.79 ± 0.23 | 0.75 ± 0.05 | - | - | [41] |

| 22.461 | (2E,4E)-2,4-Nonadienal | 5910-87-2 | 1737 | 1738 | - | - | 1.40 ± 0.42 | 1.82 ± 0.13 | 2.67 ± 0.11 | 4.54 ± 0.54 | [42] |

| 23.108 | Methyl undecanoate | 1731-86-8 | 1761 | 1732 | 1.85 ± 0.88 | 2.24 ± 0.91 | 2.22 ± 0.10 | 2.98 ± 0.03 | 3.66 ± 0.58 | - | [35] |

| 25.511 | (2E,4E)-Deca-2,4-dienal | 25152-84-5 | 1849 | 1854 | 5.98 ± 0.19 | 11.55 ± 4.25 | 12.37 ± 1.02 | 14.61 ± 0.10 | 18.28 ± 0.97 | 30.17 ± 3.80 | [33] |

| 26.124 | Methyl laurate | 111-82-0 | 1871 | 1834 | 1.07 ± 0.06 | 1.44 ± 0.36 | 2.00 ± 0.19 | 2.39 ± 0.18 | 2.43 ± 0.12 | 2.99 ± 0.52 | [35] |

| 27.199 | 1,1-Dimethoxyoctane | 10022-28-3 | 1908 | 1530 | - | - | 0.48 ± 0.07 | 0.44 ± 0.03 | 0.46 ± 0.02 | 0.55 ± 0.10 | [33] |

| 28.99 | methyl 8-oxooctanoate | 3884-92-2 | 1963 | 1334 | - | - | 0.88 ± 0.36 | 1.25 ± 0.03 | 1.40 ± 0.10 | 3.03 ± 0.48 | NIST Library |

| 32.389 | methyl 9-oxononanoate | 1931-63-1 | 2082 | 1436 | - | 2.93 ± 1.88 | 8.45 ± 3.68 | 12.73 ± 0.63 | 14.84 ± 1.95 | 32.43 ± 5.86 | [43] |

| RT | Name | CAS | Actual RI | Theoretical RI | Content (μg/g) | References | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 h | 1 h | 2 h | 4 h | 8 h | 12 h | ||||||

| 8.706 | Decane | 124-18-5 | 1060 | 1000 | 7.57 ± 0.25 | 6.34 ± 0.41 | 5.28 ± 0.44 | 6.21 ± 0.51 | 6.60 ± 1.37 | - | NIST Library |

| 9.684 | Hexanal | 66-25-1 | 1110 | 1110 | - | 66.82 ± 3.84 | 100.30 ± 2.42 | 115.63 ± 3.38 | 137.83 ± 5.91 | 160.42 ± 5.86 | [33] |

| 10.714 | Undecane | 1120-21-4 | 1164 | 1100 | 6.54 ± 0.13 | 6.57 ± 0.42 | 9.74 ± 0.23 | 5.34 ± 0.71 | 5.10 ± 0.14 | 5.60 ± 0.66 | NIST Library |

| 10.783 | 2-Butylfuran | 4466-24-4 | 1168 | 1123 | - | - | - | - | 8.17 ± 1.01 | 11.54 ± 0.97 | [44] |

| 11.607 | 2-Heptanone | 110-43-0 | 1211 | 1213 | - | - | - | 19.71 ± 3.38 | 22.33 ± 3.22 | 20.52 ± 0.49 | [45] |

| 11.755 | Methyl hexoate | 106-70-7 | 1219 | 1208 | - | - | 38.46 ± 1.13 | 56.57 ± 2.64 | 61.88 ± 5.47 | 66.72 ± 2.50 | [46] |

| 12.144 | Trans-2-Hexenal | 6728-26-3 | 1242 | 1247 | - | 24.82 ± 0.71 | 29.66 ± 1.23 | 33.59 ± 0.71 | 33.18 ± 1.10 | 33.30 ± 1.01 | [47] |

| 12.459 | pentanol | 71-41-0 | 1260 | 1260 | - | 32.06 ± 4.29 | 34.62 ± 11.81 | 38.68 ± 1.26 | 45.53 ± 1.17 | - | [48] |

| 12.694 | 2-Amylfuran | 3777-69-3 | 1273 | 1261 | - | 105.10 ± 8.18 | 126.24 ± 5.94 | 426.16 ± 10.27 | 750.35 ± 78.37 | 1063.53 ± 41.40 | [49] |

| 13.026 | 3-Octanone | 106-68-3 | 1292 | 1284.7 | - | - | - | 14.87 ± 1.90 | 25.07 ± 0.62 | 25.58 ± 0.87 | [36] |

| 13.1 | 3-dodecene | 7206-14-6 | 1296 | 1237 | - | - | - | 16.83 ± 2.72 | 27.65 ± 1.04 | 37.66 ± 2.34 | [50] |

| 13.632 | Methyl heptanoate | 106-73-0 | 1326 | 1302 | - | 87.48 ± 0.75 | 114.75 ± 7.82 | 223.79 ± 7.03 | 297.36 ± 18.89 | 343.64 ± 3.52 | [51] |

| 13.764 | (z)-1,1-diethoxy-3-hexene | 73545-18-3 | 1334 | 1272 | - | 9.54 ± 0.89 | 10.23 ± 0.79 | 20.59 ± 0.66 | - | - | NIST Library |

| 14.113 | Heptenal | 18829-55-5 | 1354 | 1342 | 6.78 ± 1.10 | 398.25 ± 6.82 | 471.01 ± 4.43 | 545.89 ± 8.76 | 560.60 ± 8.03 | 568.92 ± 10.64 | [52] |

| 15.624 | Methyl octylate | 111-11-5 | 1437 | 1437 | 214.40 ± 3.64 | 1723.38 ± 19.85 | 2482.75 ± 11.93 | 3183.01 ± 111.91 | 3976.52 ± 51.04 | 4509.02 ± 319.78 | [35] |

| 16.207 | (2E)-2-Octenal | 2548-87-0 | 1467 | 1467 | - | 137.32 ± 2.92 | 175.45 ± 0.24 | 357.51 ± 26.60 | 467.40 ± 13.88 | 511.40 ± 23.08 | [36] |

| 16.264 | Trans-2-Octen-1-ol | 18409-17-1 | 1470 | 1470 | - | 42.75 ± 2.44 | 68.70 ± 5.71 | - | - | - | [37] |

| 16.465 | methyl (Z)-4-octenoate | 21063-71-8 | 1481 | 1481 | - | 16.46 ± 0.40 | 33.12 ± 2.87 | 49.69 ± 8.52 | 81.51 ± 5.68 | 102.39 ± 2.84 | [53] |

| 17.809 | Methyl nonanoate | 1731-84-6 | 1544 | 1536 | - | 13.54 ± 1.05 | 21.94 ± 0.03 | 52.14 ± 2.36 | 96.58 ± 9.41 | 145.53 ± 4.48 | [35] |

| 17.947 | (E)-3-nonen-2-one | 18402-83-0 | 1551 | 1523 | - | 19.59 ± 0.37 | 25.12 ± 3.93 | 39.89 ± 1.83 | 50.35 ± 1.68 | 53.31 ± 1.12 | [54] |

| 18.342 | Amyl hexanoate | 540-07-8 | 1569 | 1525 | - | - | - | - | 30.43 ± 5.85 | 43.64 ± 2.12 | [55] |

| 18.576 | (2E)-2-Nonenal | 18829-56-6 | 1579 | 1574 | - | 10.28 ± 2.24 | 12.18 ± 2.14 | 27.22 ± 2.27 | 50.59 ± 6.95 | 90.72 ± 5.26 | [39] |

| 18.811 | methyl non-8-enoate | 20731-23-1 | 1590 | 1216 | - | 39.31 ± 2.15 | 51.08 ± 0.95 | 132.90 ± 3.13 | 242.29 ± 27.04 | 338.94 ± 23.28 | [56] |

| 21.46 | methyl dec-4-enoate | 1191-02-2 | 1699 | 1622 | 32.37 ± 1.29 | 67.34 ± 0.66 | 86.51 ± 8.20 | 150.70 ± 16.88 | 255.62 ± 32.40 | 321.20 ± 13.62 | [40] |

| 22.461 | (2E,4E)-2,4-Nonadienal | 5910-87-2 | 1737 | 1738 | - | 26.03 ± 3.65 | 33.16 ± 2.47 | 47.41 ± 7.33 | 85.37 ± 8.60 | 95.70 ± 15.13 | [42] |

| 24.75 | Methyl undecenate | 111-81-9 | 1822 | 1718 | - | 16.85 ± 0.85 | 27.63 ± 1.78 | 43.87 ± 7.44 | 69.06 ± 9.37 | 82.94 ± 4.83 | [40] |

| 25.511 | (2E,4E)-Deca-2,4-dienal | 25152-84-5 | 1849 | 1852 | 66.31 ± 4.92 | 884.87 ± 40.47 | 1380.79 ± 91.85 | 1634.30 ± 321.65 | 1984.50 ± 10.00 | 2207.03 ± 112.83 | [42] |

| 26.112 | methyl 10-methylundecanoate | 5129-56-6 | 1870 | 1472.4 | - | 9.35 ± 0.38 | 12.50 ± 1.33 | 12.81 ± 0.11 | 12.08 ± 3.13 | 11.64 ± 0.38 | NIST Library |

| 6.124 | Methyl laurate | 111-82-0 | 1871 | 1834 | 10.06 ± 1.08 | - | - | - | - | - | [35] |

| 28.99 | methyl 8-oxooctanoate | 3884-92-2 | 1963 | 1334 | - | 42.79 ± 1.63 | 76.8 ± 8.65 | 212.88 ± 14.91 | 438.96 ± 109.59 | 536.68 ± 52.91 | NIST Library |

| 32.389 | methyl 9-oxononanoate | 1931-63-1 | 2082 | 1436 | - | 83.94 ± 9.15 | 159.50 ± 14.13 | 360.94 ± 16.77 | 679.81 ± 168.76 | 939.94 ± 31.63 | [43] |

| 32.95 | methyl 8-hydroxyoctanoate | 20257-95-8 | 2104 | 1326 | - | - | 5.57 ± 0.58 | 44.88 ± 0.48 | 126.66 ± 24.07 | 305.03 ± 1.69 | NIST Library |

| 35.159 | 2-octyl furan | 4179-38-8 | 2232 | 1530 | - | - | - | 83.45 ± 12.28 | 246.30 ± 87.77 | 513.34 ± 19.69 | NIST Library |

| Number | RT | Name | Molecular Formula | Mass-to-Charge Ratio After Derivatization (m/z) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.23 | Hydroxy-butanal | C4H8O2 | 267 |

| 2 | 2.07 | 10-Oxo-8-decenoic acid | C10H16O3 | 363 |

| 3 | 4.41 | 9-Hydroxy-12-oxo-10-dodecenoic acid | C12H20O4 | 407 |

| 4 | 4.55 | 6-Hydroxy-heptanal | C7H14O2 | 309 |

| 5 | 4.98 | Valeraldehyde * | C5H10O | 265 |

| 6 | 5.05 | (2E)-4-Hydroxy-2-nonenal * | C9H16O2 | 335 |

| 7 | 5.07 | 4,7-Dihydroxy-heptanal | C7H12O3 | 323 |

| 8 | 5.27 | 9-Oxo-octanoic methyl ester | C11H20O3 | 365 |

| 9 | 5.48 | Hexanal * | C6H12O | 279 |

| 10 | 5.52 | Oxo-undecenoic acid | C11H18O3 | 377 |

| 11 | 5.73 | Heptenal | C7H12O | 291 |

| 12 | 6.01 | (2E)-2-Octenal * | C8H14O | 305 |

| 13 | 6.06 | (2E,4E)-2,4-Nonadienal | C9H14O | 317 |

| 14 | 6.24 | (2E)-2-Nonenal | C9H16O | 319 |

| 15 | 6.31 | (2E,4E)-Deca-2,4-dienal * | C10H16O | 331 |

| Calibration | Cross-Validation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSEC | R2C | RMSECV | R2CV | RPDCV | |

| TNF-α | 0.061 | 0.961 | 0.125 | 0.864 | 2.599 |

| IL-1β | 0.050 | 0.976 | 0.085 | 0.942 | 3.966 |

| COX-2 | 0.027 | 0.928 | 0.059 | 0.703 | 1.743 |

| Calibration | Cross-Validation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSEC | R2C | RMSECV | R2CV | RPDCV | |

| TNF-α | 0.079 | 0.940 | 0.104 | 0.912 | 3.230 |

| IL-1β | 0.191 | 0.962 | 0.250 | 0.945 | 4.079 |

| COX-2 | 0.076 | 0.942 | 0.099 | 0.917 | 3.330 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Jiao, X.; Zhao, S.; Wu, H.; Xiao, J. Using Volatile Oxidation Products to Predict the Inflammatory Capacity of Oxidized Methyl Linoleate. Foods 2025, 14, 4231. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244231

Zhang Z, Zhang L, Jiao X, Zhao S, Wu H, Xiao J. Using Volatile Oxidation Products to Predict the Inflammatory Capacity of Oxidized Methyl Linoleate. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4231. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244231

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Zhiwen, Luocheng Zhang, Xinxin Jiao, Sasa Zhao, Hua Wu, and Junsong Xiao. 2025. "Using Volatile Oxidation Products to Predict the Inflammatory Capacity of Oxidized Methyl Linoleate" Foods 14, no. 24: 4231. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244231

APA StyleZhang, Z., Zhang, L., Jiao, X., Zhao, S., Wu, H., & Xiao, J. (2025). Using Volatile Oxidation Products to Predict the Inflammatory Capacity of Oxidized Methyl Linoleate. Foods, 14(24), 4231. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244231