Effect of Red and Grey Selenium Nanoparticles on Yeast Growth: Short Communication

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis and Characterization of Selenium Nanoparticles

2.2. Preparation of Yeast Growth Medium

Experimental Design

- Control (0 mg·L−1 Se);

- Low dose: 0.5 mg·L−1 SeNPs;

- Medium dose: 5 mg·L−1 SeNPs;

- High dose: 50 mg·L−1 SeNP.

| Target Se Concentration (mg·L−1) | SeNP Stock Volume (μL) | Yeast Medium Volume (mL) | Total Volume (mL) |

| 0.5 | 32 | 9.968 | 10 |

| 5 | 316 | 9.684 | 10 |

| 50 | 3165 | 6.835 | 10 |

| 0 control | 0 | 10 | 10 |

2.3. Incubation and Growth Monitoring

Optical Density Measurements

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

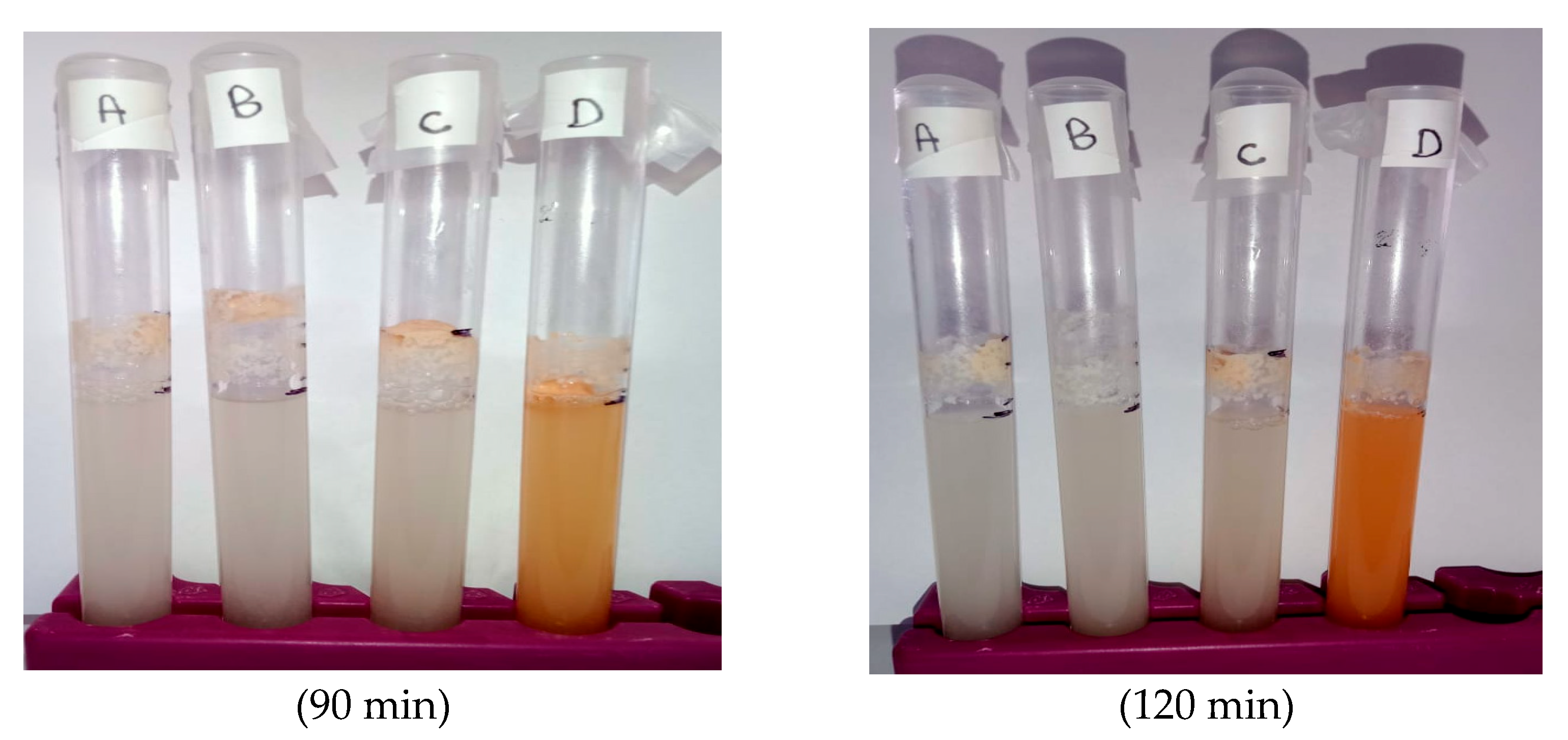

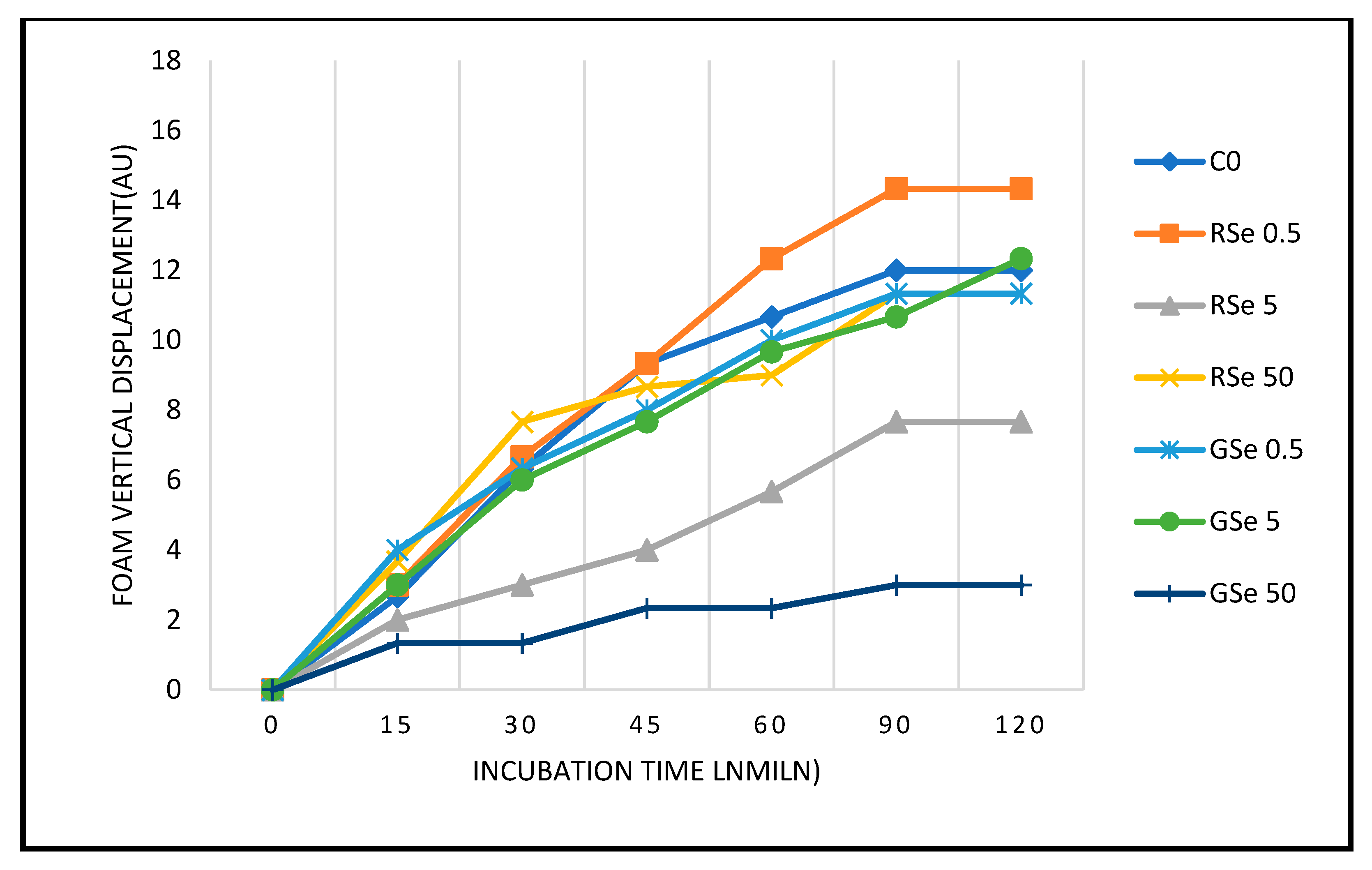

3.1. Yeast Growth Dynamics Under Selenium Nanoparticle Treatments

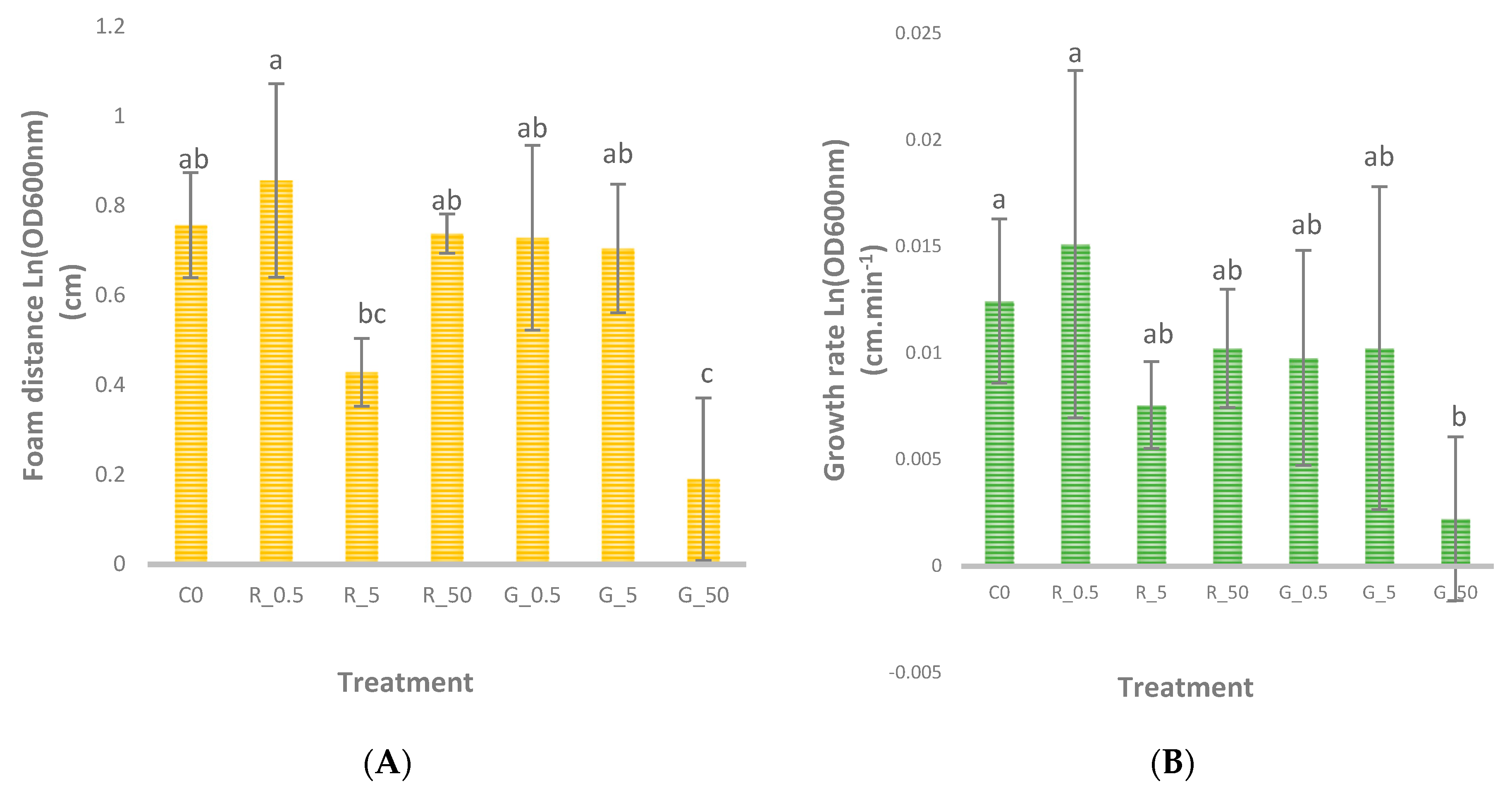

3.2. Foam Distance After 120 Minutes and Growth Rate Estimation

3.3. Role of Foam Formation and SeNP Form

3.4. Growth Kinetics and Maximum Specific Growth Rate (µmax)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Reda, F.M.; Alagawany, M.; Salah, A.S.; Mahmoud, M.A.; Azzam, M.M.; Di Cerbo, A.; El-Saadony, M.T.; Elnesr, S.S. Biological Selenium Nanoparticles in Quail Nutrition: Biosynthesis and Its Impact on Performance, Carcass, Blood Chemistry, and Cecal Microbiota. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2024, 202, 4191–4202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringuet, M.T.; Hunne, B.; Lenz, M.; Bravo, D.M.; Furness, J.B. Analysis of Bioavailability and Induction of Glutathione Peroxidase by Dietary Nanoelemental, Organic and Inorganic Selenium. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, A.; Basu, A.; Bhattacharya, S. Selenium Nanoparticles Are Less Toxic than Inorganic and Organic Selenium to Mice in Vivo. Nucleus 2019, 62, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandsuren, B.; Prokisch, J. Preparation of Red and Grey Elemental Selenium for Food Fortification. Acta Aliment. 2021, 50, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Li, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, J.; Xu, Q.; Xu, Z.; Guo, Y. Amorphous Structure and Crystal Stability Determine the Bioavailability of Selenium Nanoparticles. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 465, 133287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, F.; Zheng, S.; Wang, L.; Bai, J.; Yang, Y. Preparation of Ribes nigrum L. Polysaccharides-Stabilized Selenium Nanoparticles for Enhancement of the Anti-Glycation and α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activities. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 127122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eigenfeld, M.; Kerpes, R.; Becker, T. Understanding the Impact of Industrial Stress Conditions on Replicative Aging in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Front. Fungal Biol. 2021, 2, 665490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhalis, H. Expanding the Horizons of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae: Nutrition, Oenology, and Bioethanol Production. Sustainability 2024, 16, 11151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukinac, J.; Mastanjević, K.; Mastanjević, K.; Nakov, G.; Jukić, M. Computer Vision Method in Beer Quality Evaluation—A Review. Beverages 2019, 5, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalu, S.; Prokisch, J.; Laslo, V.; Vicas, S. Preparation, Structural Characterisation and Release Study of Novel Hybrid Microspheres Entrapping Nanoselenium, Produced by Green Synthesis. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2017, 11, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.H.D.; Vardhanabhuti, B.; Lin, M.; Mustapha, A. Antibacterial Properties of Selenium Nanoparticles and Their Toxicity to Caco-2 Cells. Food Control 2017, 77, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipović, N.; Ušjak, D.; Milenković, M.T.; Zheng, K.; Liverani, L.; Boccaccini, A.R.; Stevanović, M.M. Comparative Study of the Antimicrobial Activity of Selenium Nanoparticles With Different Surface Chemistry and Structure. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 8, 624621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryabova, Y.V.; Sutunkova, M.P.; Minigalieva, I.A.; Shabardina, L.V.; Filippini, T.; Tsatsakis, A. Toxicological Effects of Selenium Nanoparticles in Laboratory Animals: A Review. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2024, 44, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, U.; Mali, S.N.; Mandal, S. Unveiling the Ameliorative Effects of Phyto-Selenium Nanoparticles (PSeNPs) on Anti-Hyperglycemic Activity and Hyperglycemia Irradiated Complications. BioNanoScience 2025, 15, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, J.Y.; Kim, S.J.; Rhee, Y.H.; Kwon, O.H.; Park, W.H. Shape-Dependent Antimicrobial Activities of Silver Nanoparticles. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 2773–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferroudj, A.; Muthu, A.; Sári, D.; Seresné Törős, G.; Béni, Á.; El-Ramady, H.; Prokisch, J. Developing an Egg Model for Selenium Nanoparticle Testing. Acta Aliment. 2025, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, X.; Wen, J.; Xiong, X.; Hu, Y. Shape Effect on the Antibacterial Activity of Silver Nanoparticles Synthesized via a Microwave-Assisted Method. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 4489–4497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Fresneda, M.A.; Schaefer, S.; Hübner, R.; Fahmy, K.; Merroun, M.L. Exploring Antibacterial Activity and Bacterial-Mediated Allotropic Transition of Differentially Coated Selenium Nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 29958–29970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Liu, Y.; Dong, G.; Wu, H. Effect of Boiling and Frying on the Selenium Content, Speciation, and in Vitro Bioaccessibility of Selenium-Biofortified Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). Food Chem. 2021, 348, 129150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartůněk, V.; Vokatá, B.; Kolářová, K.; Ulbrich, P. Preparation of Amorphous Nano-Selenium-PEG Composite Network with Selective Antimicrobial Activity. Mater. Lett. 2019, 238, 51–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesabizadeh, T. Selenium Nanoparticles Synthesized by Pulsed Laser Ablation in Liquids for Antimicrobial Applications. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Arkansas at Little Rock, Little Rock, AR, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Gurdo, N.; Calafat, M.J.; Noseda, D.G.; Gigli, I. Production of Selenium-Enriched Yeast (Kluyveromyces marxianus) Biomass in a Whey-Based Culture Medium. Am. J. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2018, 14, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghari-Paskiabi, F.; Imani, M.; Eybpoosh, S.; Rafii-Tabar, H.; Razzaghi-Abyaneh, M. Population Kinetics and Mechanistic Aspects of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Growth in Relation to Selenium Sulfide Nanoparticle Synthesis. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Group | Maximum Specific Growth Rate (μmax) (h−1) |

|---|---|

| Control (C0) | 3.939 |

| Red SeNPs (RSe 0.5) | 4.867 |

| Grey SeNPs (GSe 0.5) | 5.73 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ferroudj, A.; Semsey, D.; Sári, D.; Prokisch, J. Effect of Red and Grey Selenium Nanoparticles on Yeast Growth: Short Communication. Foods 2025, 14, 4229. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244229

Ferroudj A, Semsey D, Sári D, Prokisch J. Effect of Red and Grey Selenium Nanoparticles on Yeast Growth: Short Communication. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4229. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244229

Chicago/Turabian StyleFerroudj, Aya, Dávid Semsey, Daniella Sári, and József Prokisch. 2025. "Effect of Red and Grey Selenium Nanoparticles on Yeast Growth: Short Communication" Foods 14, no. 24: 4229. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244229

APA StyleFerroudj, A., Semsey, D., Sári, D., & Prokisch, J. (2025). Effect of Red and Grey Selenium Nanoparticles on Yeast Growth: Short Communication. Foods, 14(24), 4229. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244229