Rhubarb as a Potential Component of an Anti-Inflammatory Diet

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Rhubarbs as Medicinal Plants

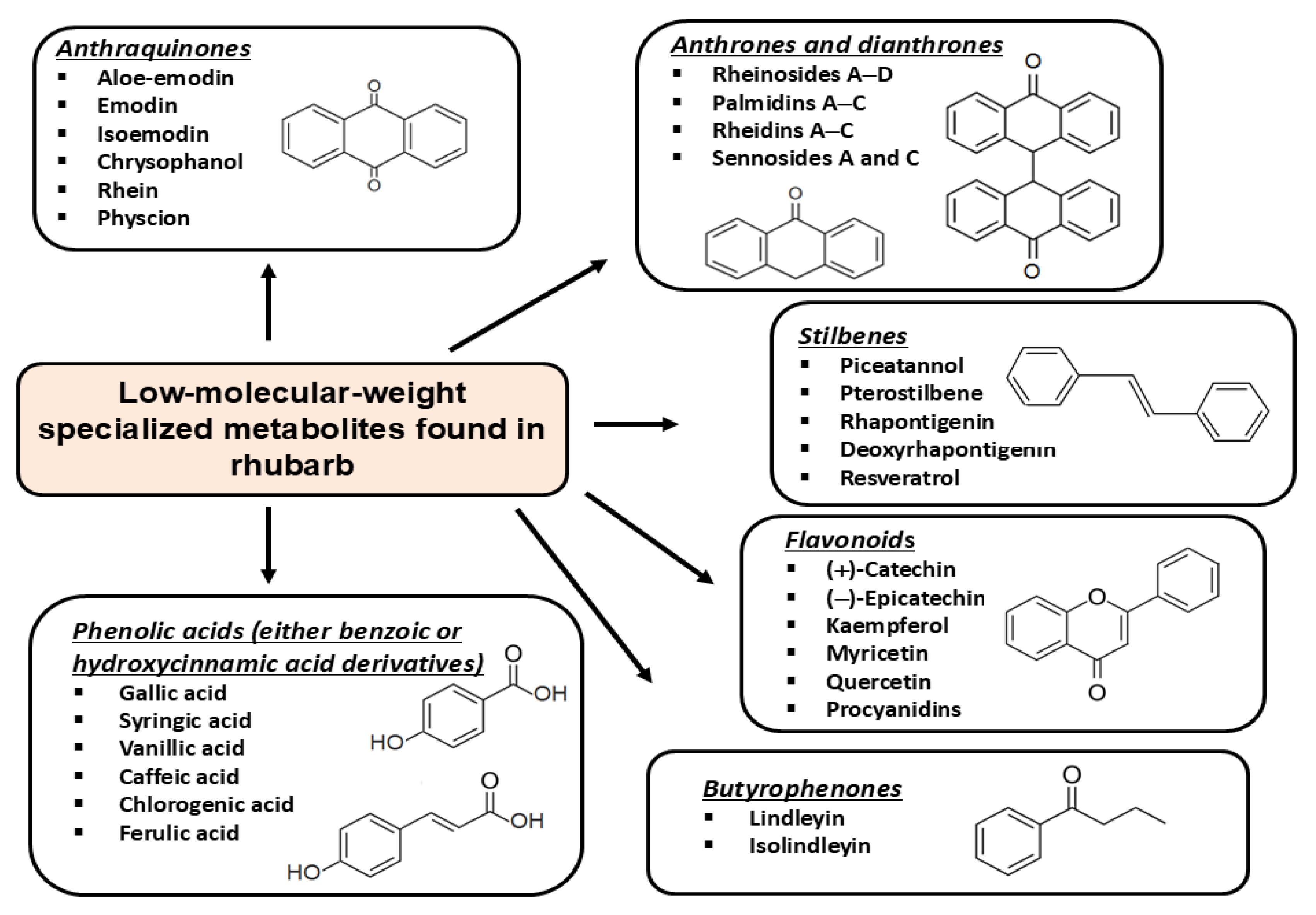

3. Phytochemical Profile of Rhubarb and Rhubarb Processing

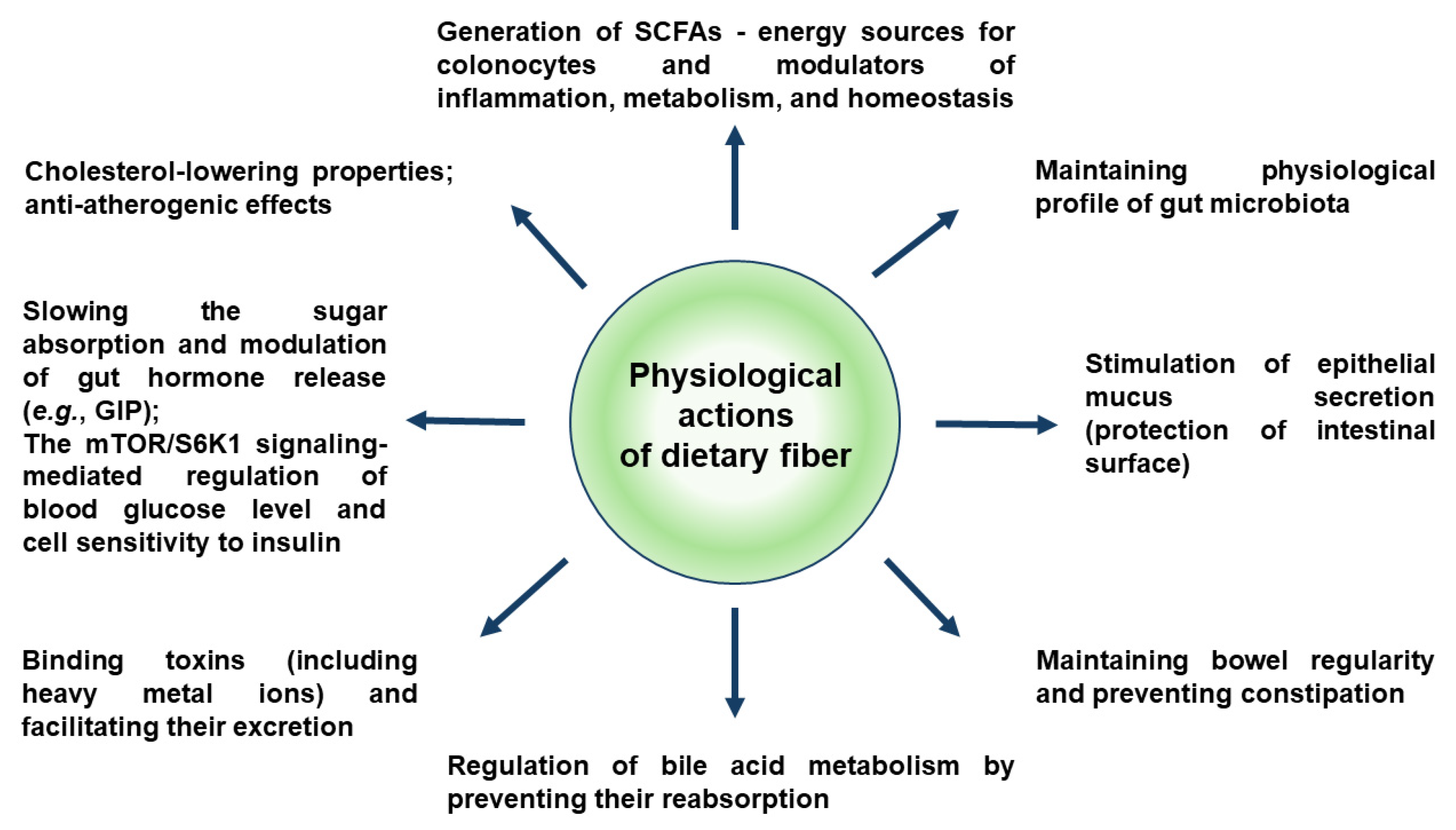

4. Rhubarbs as a Source of Dietary Fiber

5. Diverse Mechanisms of Anti-Inflammatory Action of Rhubarb-Derived Extracts and Foods

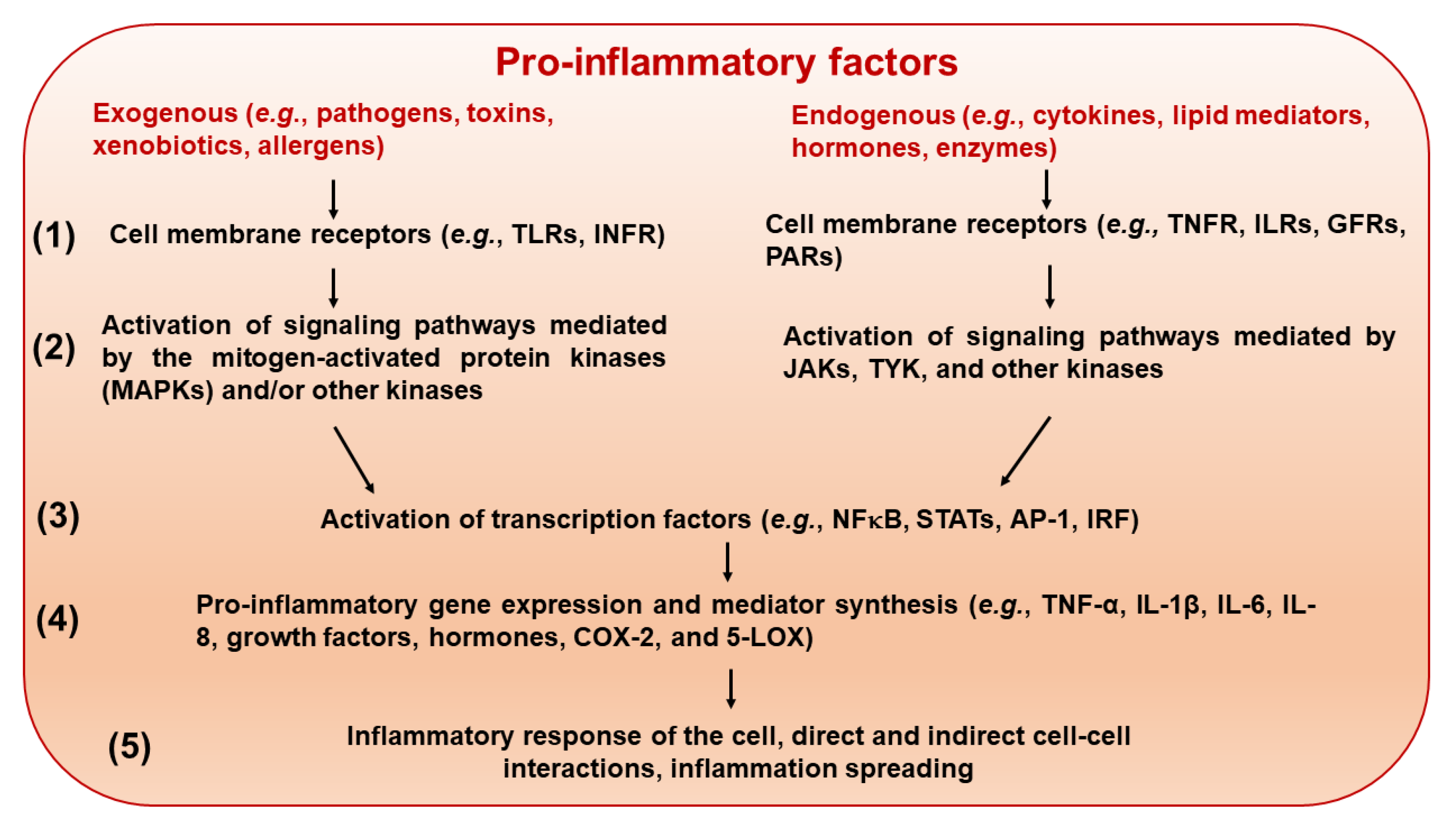

5.1. Suppression of Pro-Inflammatory Response at Different Molecular and Cellular Levels

5.2. Reduction in Oxidative Stress

| Rhubarb Species | Plant organ and Examined Substances | Assay Type | Results | Results for Reference Antioxidants | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R. emodi | n-hexane, n-butanol, ethyl acetate, dichloromethane, and water rhizome extracts | ABTS•+ and DPPH• assays | EC50 ranged from 21.52 to 2448.79 μg/mL and 90.25 to 1718.05 μg/mL, for DPPH• and ABTS•+, respectively | ascorbic acid EC50 = 70.33 and 111.06 μg/mL, for DPPH• and ABTS•+, respectively | [97] |

| R. palmatum | methanol extract from stems | DPPH• and O2•−-scavenging tests; ROS scavenging in RAW 264.7 cells | EC50 = 290 μg/mL and 480 μg/mL, respectively; ↓ NO production in RAW 264.7 cells; increase in SOD activity in RAW 264.7 cells | EC50 = 23.00 μg/mL for ascorbic acid in DPPH• tests | [44] |

| R. rhaponticum | root/rhizome infusion | DPPH• scavenging test | AOX (anti-oxidative efficiency) < 87% | AOX for ascorbic acid (1 mg/mL) was of 77% | [98] |

| stalk infusion and ethanolic extract | DPPH• scavenging test | AOX of 48 and 98%, respectively | [98] | ||

| R. rhabarbarum | the rhizome-derived rhapontigenin and rhaponticin | DPPH• scavenging test and antioxidant action in V79-4 cells | higher efficiency of rhapontigenin; enhancement of cell antioxidant activity; modulation of signaling pathways | [99] | |

| stalk extract | DPPH• scavenging | DPPH•-scavenging efficiencies of the ethyl acetate and methanol extracts (5 µg/mL): 94.12% and 96%, respectively | [100] | ||

| methanol extracts from petioles | ABTS•+ and DPPH• scavenging assays; FRAP | in the ABTS•+, DPPH•, and FRAP assays, the “Red Malinowy” variety attained 18.26, approx. 5.9 and 10 mmol/Trolox equivalents/100 g of dry mass (d.m.), respectively | [56] | ||

| n-hexane, ethyl acetate, ethanol, acetone, and water rhizome fractions | ABTS•+ and DPPH• scavenging assays | EC50 ranged from 5.67 to 93.23 μg/mL and from 41.37 to 1800.87 μg/mL, for ABTS•+ and DPPH•, respectively; the ethyl acetate extract was the most efficient one | gallic acid EC50 = 3.16 and 1.25 μg/mL, Trolox EC50 = 13.53 and 6.28 for ABTS•+, and DPPH•, respectively | [101] | |

| 7 fractions (water, 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100% methanol or acetone) isolated from petioles | experimental model of cod liver oil | the highest antioxidant activity found for 100% methanol fraction, i.e., 72.6 and 92.8% at concentrations of 20 and 100 μg/mL, respectively | antioxidant efficiency of BHT: 92.2% at 100 μg/mL; α-tocopherol: 84.8% at 100 μg/mL | [102] | |

| the rhizome-derived rhaponticin, rhapontigenin, isorhaponticin, deoxyrhaponticin, deoxyrhapontigenin, and resveratrol | ROS scavenging in RAW 264.7 cells | deoxyrhapontigenin IC50 = 32.83 μM and 28.22 μM, for ROS and peroxynitrite generation, respectively; induction of HO-1 and activation of Nrf2 via the PI3K/Akt pathway | resveratrol IC50 = 49.07 μM for ROS and 37.82 μM for peroxynitrite, respectively | [87] | |

| the rhizome-derived piceatannol, resveratrol, rhapontigenin, deoxyrhapontigenin, pterostilbene, (E)-3,5,4′-trimethoxystilbene, and trans-stilbene | HepG2 cell line exposed to arachidonic acid + iron-induced oxidative stress | reduction in the oxidative stress-induced mitochondrial dysfunction through AMPK pathway | [103] | ||

| R. ribes L. | chloroform and methanol root and stem extracts | DPPH• and O2•− scavenging tests; Fe3+ and Cu2+-reducing assays; β-carotene bleaching; ion chelation | in most tests, extracts displayed considerable efficiency when compared to reference antioxidants | ascorbic acid, α-tocopherol, BHA, BHT, quercetin | [104] |

| stem water, ethanol and methanol extracts | ABTS•+, DPPH• and •OH scavenging assays | ABTS•+ scavenging efficiency: 99.27, 99.91, and 99.88%; DPPH• scavenging efficiency: 83.11, 81.42, and 83.26%; •OH scavenging efficiency: 93.49, 94.21, and 95.86%, for stem water, ethanol and methanol extract, respectively | BHA scavenging efficiency: 95.32, 80.49, and 93.78%, for ABTS•+, DPPH•, and •OH, respectively | [105] | |

| R. officinale | methanol extract from petioles | DPPH•, •OH, O2•− scavenging assays; antioxidant activity in RAW 264.7 cells | EC50 in DPPH•-scavenging = 205.13 μg/mL ↓ lipid peroxidation protection of SOD, CAT activity | ascorbic acid EC50 in DPPH•-scavenging = 19.33 μg/mL | [43] |

| R. tanguticum | methanol extract from petioles | DPPH•, •OH, and O2•− scavenging assays; antioxidant activity in RAW 264.7 cells | EC50 in DPPH•-scavenging = 497.03 μg/mL ↓ lipid peroxidation protection of SOD, CAT activity | [43] | |

| R. telianum İlçim | ethanol extracts from leaves and seeds | DPPH• scavenging test Fe3+, Cu2+-reducing tests, FRAP assay | EC50 = 20.79 and 5.67 μg/mL, respectively, seed extract was the most effective in all reducing tests | EC50 = 16.00, 12.99, 9.63, and 13.92 μg/mL, for BHA, BHT, Trolox, and ascorbic acid respectively | [106] |

| R. turkestanicum Janischew | ethanol root extracts | pheochromocytoma (PC12) and neuroblastoma (N2a) cells | ↓ lipid peroxidation ↓ ROS generation ↓ apoptosis | [107] |

5.3. Anti-Obesity and Cardioprotective Effects

5.4. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Rhubarbs in the Digestive System

5.5. Rhubarb-Derived Polysaccharides as Immunomodulatory and Anti-Inflammatory Agents

6. Future Prospects and Challenges

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chavda, V.P.; Feehan, J.; Apostolopoulos, V. Inflammation: The cause of all diseases. Cells 2024, 13, 1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furman, D.; Campisi, J.; Verdin, E.; Carrera-Bastos, P.; Targ, S.; Franceschi, C.; Ferrucci, L.; Gilroy, D.W.; Fasano, A.; Miller, G.W.; et al. Chronic inflammation in the etiology of disease across the life span. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1822–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huston, P. A sedentary and unhealthy lifestyle fuels chronic disease progression by changing interstitial cell behaviour: A network analysis. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 904107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, M.S.; Han, C.Y.; Sukumaran, S.; Delaney, C.L.; Miller, M.D. Effect of anti-inflammatory diets on inflammation markers in adult human populations: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Nutr. Rev. 2022, 81, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wawrzyniak-Gramacka, E.; Hertmanowska, N.; Tylutka, A.; Morawin, B.; Wacka, E.; Gutowicz, M.; Zembron-Lacny, A. The association of anti-inflammatory diet ingredients and lifestyle exercise with inflammaging. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Bruzelius, M.; Damrauer, S.M.; Håkansson, N.; Wolk, A.; Åkesson, A.; Larsson, S.C. Anti-inflammatory diet and incident peripheral artery disease: Two prospective cohort studies. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 41, 1191–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricker, M.A.; Haas, W.C. Anti-inflammatory diet in clinical practice: A review. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2017, 32, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stromsnes, K.; Correas, A.G.; Lehmann, J.; Gambini, J.; Olaso-Gonzalez, G. Anti-Inflammatory properties of diet: Role in healthy aging. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Pu, H.; Voss, M. Overview of anti-inflammatory diets and their promising effects on non-communicable diseases. Br. J. Nutr. 2024, 132, 898–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakadate, K.; Ito, N.; Kawakami, K.; Yamazaki, N. Anti-Inflammatory actions of plant-derived compounds and prevention of chronic diseases: From molecular mechanisms to applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieira, S.F.; Reis, R.L.; Ferreira, H.; Neves, N.M. Plant-derived bioactive compounds as key players in the modulation of immune-related conditions. Phytochem. Rev. 2025, 24, 343–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.X.; Liu, M.C. Separation procedures for the pharmacologically active components of rhubarb. J. Chromatogr. B Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2004, 812, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Dai, L.; Yan, F.; Ma, Y.; Guo, X.; Jenis, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Miao, X.; Shang, X. The phytochemistry and pharmacology of three Rheum species: A comprehensive review with future perspectives. Phytomedicine 2024, 131, 155772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Jugran, A.K.; Bargali, S.S.; Bhatt, I.D. Ethno-medicinal uses, ecology, phytochemistry, biological activities, and conservation approaches for Himalayan rhubarb species. Nat. Prod. Res. 2025, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rokaya, M.B.; Münzbergová, Z.; Timsina, B. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants from the Humla district of western Nepal. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 130, 485–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Aslam, M.; Masoodi, T.H.; Bhat, M.A.; Kongala, P.R.; Husaini, A.M. The Himalayan rhubarb (Rheum australe D. Don.): An endangered medicinal herb with immense ethnobotanical ‘use-value’. Vegetos 2025, 38, 441–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsering, J.; Tag, H. High altitude ethnomedicinal plants of Western Arunachal Himalayan Landscape. Pleione 2015, 9, 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bisht, V.K.; Kandari, L.S.; Negi, J.S.; Bhandari, A.K.; Sundriyal, R.C. Traditional use of medicinal plants in district Chamoli, Uttarakhand, India. J. Med. Plant Res. 2013, 7, 918–929. [Google Scholar]

- Lal, B.; Singh, K.N. Indigenous herbal remedies to cure skin disorders by the natives of Lahaul-Spiti in Himachal Pradesh. Indian J. Tradit. Knowl. 2008, 7, 237–241. [Google Scholar]

- Rakhmataliev, A.; Togaev, A.; Ergashov, I.; Yusupov, Z. Ethnomedicinal and nutritional applications of Rheum maximowiczii Losinsk. in traditional medicine in Uzbekistan. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2025, 31, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, M.; Li, J.; He, M.; Ouyang, H.; Ruan, L.; Huang, X.; Rao, Y.; Yang, S.; Zhou, X.; Bai, J. Investigation and identification of the multiple components of Rheum officinale Baill. using ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with quadrupole-time-of-flight tandem mass spectrometry and data mining strategy. J. Sep. Sci. 2021, 44, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ma, Y.P.; Zhang, Z.; Dai, P.L.; Li, P.; Li, W.G. Effects of adding Rheum officinale to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers on renal function in patients with chronic renal failure: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin. Nephrol. 2018, 89, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.-Y.; Chan, S.-W.; Guo, D.-J.; Yu, P.H.F. Correlation between antioxidative power and anticancer activity in herbs from Traditional Chinese Medicine formulae with anticancer therapeutic effect. Pharm. Biol. 2007, 45, 541–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shia, C.S.; Juang, S.H.; Tsai, S.Y.; Chang, P.H.; Kuo, S.C.; Hou, Y.C.; Chao, P.D. Metabolism and pharmacokinetics of anthraquinones in Rheum palmatum in rats and ex vivo antioxidant activity. Planta Med. 2009, 75, 1386–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolodziejczyk-Czepas, J.; Liudvytska, O. Rheum rhaponticum and Rheum rhabarbarum: A review of phytochemistry, biological activities and therapeutic potential. Phytochem. Rev. 2021, 20, 589–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.L.; Ma, Y.M.; Yan, D.M.; Zhou, H.; Shi, R.; Wang, T.M.; Yang, Y.; Wang, C.H.; Zhang, N. Effective constituents in xiexin decoction for anti-inflammation. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009, 125, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nedelcheva, A. Medicinal plants from an old Bulgarian medical book. J. Med. Plant. Res. 2012, 6, 2324–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oskay, M.; Karayildirim, T.; Ay, E.; Ay, K. Determination of some chemical parameters and antimicrobial activity of traditional food: Mesir paste. J. Med. Food 2010, 13, 1195–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, F.; Nie, X.; Yang, L.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Zhou, G. Non-target metabolomics revealed the differences between Rh. tanguticum plants growing under canopy and open habitats. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofi, I.I.; Zargar, S.A.; Ganie, A.H.; Shah, M.A. Distribution dynamics of Arnebia euchroma (Royle) I. M. Johnst. and associated plant communities in Trans-Himalayan Ladakh region in relation to local livelihoods under climate change. Trees For. People 2022, 7, 100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.J.; Pu, Z.J.; Tang, Y.P.; Shen, J.; Chen, Y.Y.; Kang, A.; Zhou, G.S.; Duan, J.A. Advances in bio-active constituents, pharmacology and clinical applications of rhubarb. Chin. Med. 2017, 12, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, S.; Kaloo, Z.A.; Singh, S.; Bashir, I. Medicinal importance of genus Rheum—A review. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2014, 2, 261–267. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, H.; Qin, L.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Lu, Z.; Wei, S.; Gao, X.; Tu, P. Global chemical profiling based quality evaluation approach of rhubarb using ultra performance liquid chromatography with tandem quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry. J. Sep. Sci. 2015, 38, 511–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Liu, Z.; Ma, B.; An, L.; Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Guo, L.; Gao, W. Active ingredients, nutrition values and health-promoting effects of aboveground parts of rhubarb: A review. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.; Li, L.; Hu, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, C.; Wei, S. Influence of the environmental factors on the accumulation of the bioactive ingredients in Chinese rhubarb products. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0154649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeoka, G.R.; Dao, L.; Harden, L.; Pantoja, A.; Kuhl, J.C. Antioxidant activity, phenolic and anthocyanin contents of various rhubarb (Rheum spp.) varieties. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 48, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalisz, S.; Oszmiański, J.; Kolniak-Ostek, J.; Grobelna, A.; Kieliszek, M.; Cendrowski, A. Effect of a variety of polyphenols compounds and antioxidant properties of rhubarb (Rheum rhabarbarum). LWT 2020, 118, 108775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cojocaru, A.; Vlase, L.; Munteanu, N.; Stan, T.; Teliban, G.C.; Burducea, M.; Stoleru, V. Dynamic of phenolic compounds, antioxidant activity, and yield of rhubarb under chemical, organic and biological fertilization. Plants 2020, 9, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhao, S.; Li, J.; Zhou, G. Metabolomics analysis reveals the metabolite profiles of Rheum tanguticum grown under different altitudinal gradients. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paudel, B.R.; Subedi, C.K.; Ghimire, S.K.; Pyakurel, D.; Rajbhandari, M.; Chaudhary, R.P. Impacts of climate change on the distribution pattern of Himalayan Rhubarb (Rheum australe D. Don) in Nepal Himalaya. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0323755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Y.; Yan, P.-J.; Fan, P.-X.; Lu, S.-S.; Li, M.-Y.; Fu, X.-Y.; Wei, S.-B. The application of rhubarb concoctions in traditional Chinese medicine and its compounds, processing methods, pharmacology, toxicology and clinical research. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1442297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Deng, C.; Song, X.; Zhang, D. Botany, traditional use, phytochemistry, pharmacology and clinical applications of rhubarb (Rhei Radix et Rhizome): A systematic review. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2024, 52, 1925–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.X.; Miao, X.; Yang, X.R.; Zuo, L.P.; Lan, Z.H.; Li, B.; Shang, X.F.; Yan, F.Y.; Guo, X.; Wang, Y.; et al. High value-added application of two renewable sources as healthy food: The nutritional properties, chemical compositions, antioxidant, and antiinflammatory activities of the stalks of Rheum officinale Baill. and Rheum tanguticum Maxim. ex Regel. Front. Nutr. 2022, 8, 770264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, X.; Dai, L.; He, J.; Yang, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, B.; Zhang, J.; Pan, H.; Gulnaz, I. A high-value-added application of the stems of Rheum palmatum L. as a healthy food: The nutritional value, chemical composition, and anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 4901–4913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasper, I.; Ventskovskiy, B.M.; Rettenberger, R.; Heger, P.W.; Riley, D.S.; Kaszkin-Bettag, M. Long-term efficacy and safety of the special extract ERr731 of Rheum rhaponticum in perimenopausal women with menopausal symptoms. Menopause 2009, 16, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaszkin-Bettag, M.; Ventskovskiy, B.M.; Solskyy, S.; Beck, S.; Hasper, I.; Kravchenko, A.; Rettenberger, R.; Richardson, A.; Heger, P.W. Confirmation of the efficacy of ERr731 in perimenopausal women with menopausal symptoms. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2009, 15, 24–34. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.; Hu, C.J.; Pan, X.; Geng, Y.Y.; Cheng, Z.M.; Xiong, R. Comparative study on influences of long-term use of raw rhubarb and stewed rhubarb on functions of liver and kidney in rats. Chin. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2015, 35, 1384–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Sun, J.; Li, S.; Qi, Y.; Luo, M.; Dong, L.; Chen, J. Scorch processing of rhubarb (Rheum tanguticum Maxim. ex Balf.) pyrolyzed anthraquinone glucosides into aglycones and improved the therapeutic effects on thromboinflammation via regulating the complement and coagulation cascades pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 333, 118475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougall, G.J.; Dobson, P.; Jordan-Mahy, N. Effect of different cooking regimes on rhubarb polyphenols. Food Chem. 2010, 119, 758–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, G.P.; Vanhanen, L.; Mason, S.M.; Ross, A.B. Effect of cooking on the soluble and insoluble oxalate content of some New Zealand foods. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2000, 13, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faudon, S.; Savage, G. Manufacture of a low oxalate mitsumame-type dessert using rhubarb juice and calcium salts. Food Nutr. Sci. 2014, 5, 1621–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.V.H.; Savage, G.P. Oxalate bioaccessibility in raw and cooked rhubarb (Rheum rhabarbarum L.) during in vitro digestion. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2020, 94, 103648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korus, A.; Korus, J. Enhancing nutritional value of rhubarb (Rheum rhaponticum L.) products: The role of fruit and vegetable pomace. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, S.M.; Moon, K.D.; Lee, C.Y. Rhubarb juice as a natural antibrowning agent. Food Sci. 2000, 65, 1288–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojdyło, A.; Oszmiański, J.; Bober, I. The effect of addition of chokeberry, flowering quince fruits and rhubarb juice to strawberry jams on their polyphenol content, antioxidant activity and colour. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2008, 227, 1043–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oszmiański, J.; Wojdyło, A. Polyphenol content and antioxidative activity in apple purées with rhubarb juice supplement. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2008, 43, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göksu, F.; Özlü, Z.; Bölek, S. Rhubarb powder: Potential uses as a functional bread ingredient. J. Food Sci. 2024, 89, 2017–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, S.; Hajir, J.; Sukhobaevskaia, V.; Weickert, M.O.; Pfeiffer, A.F.H. Impact of dietary fiber on inflammation in humans. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margină, D.; Ungurianu, A.; Purdel, C.; Tsoukalas, D.; Sarandi, E.; Thanasoula, M.; Tekos, F.; Mesnage, R.; Kouretas, D.; Tsatsakis, A. Chronic inflammation in the context of everyday life: Dietary changes as mitigating factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deleu, S.; Machiels, K.; Raes, J.; Verbeke, K.; Vermeire, S. Short chain fatty acids and its producing organisms: An overlooked therapy for IBD? eBioMedicine 2021, 66, 103293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Guo, J.; Kang, S.-G.; Huang, K.; Tong, T. Olfr78, a novel short-chain fatty acid receptor, regulates glucose homeostasis and gut GLP-1 secretion in mice. Food Front. 2023, 4, 1893–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotlo, K.; Anbazhagan, A.N.; Priyamvada, S.; Jayawardena, D.; Kumar, A.; Chen, Y.; Xia, Y.; Finn, P.W.; Perkins, D.L.; Dudeja, P.K.; et al. The olfactory G protein-coupled receptor (Olfr-78/OR51E2) modulates the intestinal response to colitis. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2020, 318, 502–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, V.; Bachheti, R.K.; Chand, T.; Barman, A. Dietary fibre and human health. Int. J. Food Saf. Nutr. Public Health 2011, 4, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, V.; Cheema, S.K.; Agellon, L.B.; Ooraikul, B.; Basu, T.K. Dietary rhubarb (Rheum rhaponticum) stalk fibre stimulates cholesterol 7a-hydroxylase gene expression and bile acid excretion in cholesterol-fed C57BL/6J mice. Br. J. Nutr. 1999, 81, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunzel, M.; Seiler, A.; Steinhart, H. Characterization of dietary fiber lignins from fruits and vegetables using the DFRC method. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 9553–9559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, C.L.R.; Wilairatana, P.; Silva, L.R.; Moreira, P.S.; Vilar Barbosa, N.M.M.; da Silva, P.R.; Coutinho, H.D.M.; de Menezes, I.R.A.; Felipe, C.F.B. Biochemical aspects of the inflammatory process: A narrative review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 168, 115764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Deng, H.; Cui, H.; Fang, J.; Zuo, Z.; Deng, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, L. Inflammatory responses and inflammation-associated diseases in organs. Oncotarget 2017, 9, 7204–7218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sözmen, A.B.; Yıldırım Sözmen, E. Biochemistry of inflammation: Its mediators and activities. In Inflammation and In Vitro Diagnostics, 1st ed.; Koçdor, H., Pabuççuoğlu, A., Zihnioğlu, F., Eds.; Türkiye Klinikleri: Ankara, Turkye, 2024; pp. 6–12. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, L.S. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and their risk: A story still in development. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2013, 15 (Suppl. 3), S1–S2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, E.M.; Heasley, B.H.; Chordia, M.D.; Macdonald, T.L. In vitro metabolism of 2-acetylbenzothiophene: Relevance to zileuton hepatotoxicity. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2004, 17, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azab, A.; Nassar, A.; Azab, A.N. Anti-inflammatory activity of natural products. Molecules 2016, 21, 1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olajide, O.A.; Sarker, S.D. Alzheimer’s disease: Natural products as inhibitors of neuroinflammation. Inflammopharmacology 2020, 28, 1439–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambati, G.G.; Jachak, S.M. Natural product inhibitors of cyclooxygenase (COX) enzyme: A review on current status and future perspectives. Curr. Med. Chem. 2021, 28, 1877–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.B.; Yang, Y.G.; Xu, H.L.; Yuan, M.M.; Chen, S.Z.; Song, Z.X.; Tang, Z.S. Screening 5-lipoxygenase inhibitors from selected traditional Chinese medicines and isolation of the active compounds from Polygoni Cuspidati Rhizoma by an on-line bioactivity evaluation system. Biomed. Chromatogr. 2022, 36, e5426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, N.; Shukla, A.; Makhal, P.N.; Kaki, V.R. Natural product-driven dual COX-LOX inhibitors: Overview of recent studies on the development of novel anti-inflammatory agents. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolodziejczyk-Czepas, J.; Czepas, J. Rhaponticin as an anti-inflammatory component of rhubarb—A minireview of the current state of the art and prospects for future research. Phytochem. Rev. 2019, 18, 1375–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharanya, C.S.; Arun, K.G.; Sabu, A.; Haridas, M. Aloe emodin shows high affinity to active site and low affinity to two other sites to result consummately reduced inhibition of lipoxygenase. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2020, 150, 106453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutil, Z.; Kvasnicova, M.; Temml, V.; Schuster, D.; Marsik, P.; Fernandez Cusimamani, E.; Lou, J.-D.; Vanek, T.; Landa, P. Effect of dietary stilbenes on 5-lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenases activities in vitro. Int. J. Food Prop. 2015, 18, 1471–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liudvytska, O.; Ponczek, M.B.; Ciesielski, O.; Krzyżanowska-Kowalczyk, J.; Kowalczyk, M.; Balcerczyk, A.; Kolodziejczyk-Czepas, J. Rheum rhaponticum and Rheum rhabarbarum extracts as modulators of endothelial cell inflammatory response. Nutrients 2023, 15, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zhang, L.; Joo, D.; Sun, S.C. NF-κB signaling in inflammation. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2017, 2, 17023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Zhong, Z.; Karin, M. NF-κB: A double-edged sword controlling inflammation. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, A.; Islam, A.U.; Prakash, H.; Singh, S. Phytochemicals targeting NF-κB signaling: Potential anti-cancer interventions. J. Pharm. Anal. 2022, 12, 394–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Huang, W.; Luo, Y.; Xiang, L.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Xu, C.; Meng, X.; Wang, P. Assessment of the anti-inflammatory effects of three rhubarb anthraquinones in LPS-Stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages using a pharmacodynamic model and evaluation of the structure-activity relationships. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 273, 114027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stompor-Gorący, M. The health benefits of emodin, a natural anthraquinone derived from rhubarb—A summary update. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Bian, Y.; Lu, B.; Wang, D.; Azami, N.L.B.; Wei, G.; Ma, F.; Sun, M. Rhubarb free anthraquinones improved mice nonalcoholic fatty liver disease by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome. J. Transl. Med. 2022, 20, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Liu, X.; Yi, Q.; Qiao, G.; Wang, L.; Chen, L.; Fan, L.; Li, Y.; Duan, L.; Huang, L.; et al. Free total rhubarb anthraquinones protect intestinal mucosal barrier of SAP rats via inhibiting the NLRP3/caspase-1/GSDMD pyroptotic pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 326, 117873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joo Choi, R.; Cheng, M.S.; Shik Kim, Y. Desoxyrhapontigenin up-regulates Nrf2-mediated heme oxygenase-1 expression in macrophages and inflammatory lung injury. Redox Biol. 2014, 2, 504–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liudvytska, O.; Bandyszewska, M.; Skirecki, T.; Krzyżanowska-Kowalczyk, J.; Kowalczyk, M.; Kolodziejczyk-Czepas, J. Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant actions of extracts from Rheum rhaponticum and Rheum rhabarbarum in human blood plasma and cells in vitro. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 165, 115111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wu, J.; Tian, R.; Su, S.; Deng, S.; Meng, X. Targeting foam cell formation and macrophage polarization in atherosclerosis: The therapeutic potential of rhubarb. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 129, 110433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Zhao, F.; Cheng, H.; Su, M.; Wang, Y. Macrophage polarization: An important role in inflammatory diseases. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1352946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajčević, N.; Bukvički, D.; Dodoš, T.; Marin, P.D. Interactions between natural products—A review. Metabolites 2022, 12, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, M.K.; Kang, D.G.; Lee, J.K.; Kim, J.S.; Lee, H.S. Vasodilatory and anti-inflammatory effects of the aqueous extract of rhubarb via a NO-cGMP pathway. Life Sci. 2006, 78, 1550–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.H.; Yu, J.K.; Moon, Y.S. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of different parts of rhubarb (Rheum rhabarbarum) compared with da huang root (R. officinale). Korean J. Food Preserv. 2022, 29, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, R.J. Oxidative stress and inflammation in cardiovascular diseases. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kris-Etherton, P.M.; Hecker, K.D.; Bonanome, A.; Coval, S.M.; Binkoski, A.E.; Hilpert, K.F.; Griel, A.E.; Etherton, T.D. Bioactive compounds in foods: Their role in the prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer. Am. J. Med. 2002, 113, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalpana, D.; Velmurugan, N.; Wahab, R.; Cho, J.Y.; Hwang, I.H.; Lee, Y.S. GC-MS analysis and evaluation of antimicrobial, free radical scavenging and in vitro cytotoxic activities of the methanolic extract of Rheum undulatum. Sci. Adv. Mater. 2012, 4, 1238–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.K.; Lee, Y.K. Antioxidant activity in Rheum emodi Wall (Himalayan rhubarb). Molecules 2021, 26, 2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raudsepp, P.; Anton, D.; Roasto, M.; Meremäe, K.; Pedastsaar, P.; Mäesaar, M.; Raal, A.; Laikoja, K.; Püssa, T. The antioxidative and antimicrobial properties of the blue honeysuckle (Lonicera caerulea L.), Siberian rhubarb (Rheum rhaponticum L.) and some other plants, compared to ascorbic acid and sodium nitrite. Food Control 2013, 31, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Kang, K.A.; Piao, M.J.; Lee, K.H.; Jang, H.S.; Park, M.J.; Kim, B.J.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, Y.S.; Ryu, S.Y.; et al. Rhapontigenin from Rheum undulatum protects against oxidative stress-induced cell damage through antioxidant activity. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A 2007, 70, 1155–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.W.; Lee, C.C.; Hsu, W.H.; Hengel, M.; Shibamoto, T. Antioxidant activity of natural plant extracts from mate (Ilex paraguariensis), lotus plumule (Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn.) and rhubarb (Rheum rhabarbarum L.). J. Food Nutr. Disord. 2017, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jargalsaikhan, G.; Wu, J.-Y.; Chen, Y.-C.; Yang, L.-L.; Wu, M.-S. Comparison of the phytochemical properties, antioxidant activity and cytotoxic effect on HepG2 Cells in Mongolian and Taiwanese rhubarb species. Molecules 2021, 26, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won Jang, H.; Hsu, W.H.; Hengel, M.J.; Shibamoto, T. Antioxidant activity of rhubarb (Rheum rhabarbarum L.) extract and its main component emodin. Nat. Prod. Chem. Res. 2018, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, G.Z.; Lee, Y.I.; Jeong, J.H.; Zhao, H.Y.; Jeon, R.; Lee, H.J.; Ryu, J.H. Stilbenoids from Rheum undulatum protect hepatocytes against oxidative stress through AMPK activation. Phytother. Res. 2015, 29, 1605–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ӧztürk, M.; Aydomuş-Ӧztürk, F.; Duru, M.C.; Topçu, G. Antioxidant activity of stem and root extracts of rhubarb (Rheum ribes): An edible medicinal plant. Food Chem. 2007, 103, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keser, S.; Keser, F.; Karatepe, M.; Kaygili, O.; Tekin, S.; Turkoglu, I.; Demir, E.; Yilmaz, O.; Kirbag, S.; Sandal, S. Bioactive contents, In vitro antiradical, antimicrobial and cytotoxic properties of rhubarb (Rheum ribes L.) extracts. Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 34, 3353–3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tel, A.Z.; Aslan, K.; Yılmaz, M.A.; Gulcin, İ. A multidimensional study for design of phytochemical profiling, antioxidant potential, and enzyme inhibition effects of ışgın (Rheum telianum) as an edible plant. Food Chem. X 2025, 25, 102125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabian, A.; Sadeghnia, H.R.; Moradzadeh, M.; Hosseini, A. Rheum turkestanicum reduces glutamate toxicity in PC12 and N2a cell lines. Folia Neuropathol. 2018, 56, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bays, H.E.; Kirkpatrick, C.F.; Maki, K.C.; Toth, P.P.; Morgan, R.T.; Tondt, J.; Christensen, S.M.; Dixon, D.L.; Jacobson, T.A. Obesity, dyslipidemia, and cardiovascular disease: A joint expert review from the Obesity Medicine Association and the National Lipid Association 2024. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2024, 18, 320–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soták, M.; Clark, M.; Suur, B.E.; Börgeson, E. Inflammation and resolution in obesity. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2025, 21, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liudvytska, O.; Kolodziejczyk-Czepas, J. A review on rhubarb-derived substances as modulators of cardiovascular risk factors—A special emphasis on anti-obesity action. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Wang, E.; Ma, L.; Zhai, P. Dietary resveratrol increases the expression of hepatic 7α-hydroxylase and ameliorates hypercholesterolemia in high-fat fed C57BL/6J mice. Lipids Health Dis. 2012, 11, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, S.-M.; Lee, S.-A.; Choi, M.-S. Antiobesity and vasoprotective effects of resveratrol in ApoE-deficient mice. J. Med. Food 2014, 17, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rašković, A.; Ćućuz, V.; Torović, L.; Tomas, A.; Gojković-Bukarica, L.; Ćebović, T.; Milijašević, B.; Stilinović, N.; Cvejić Hogervorst, J. Resveratrol supplementation improves metabolic control in rats with induced hyperlipidemia and type 2 diabetes. Saudi Pharm. J. 2019, 27, 1036–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira Andrade, J.M.; Frade, A.C.; Guimarães, J.B.; Freitas, K.M.; Lopes, M.T.; Guimarães, A.L.; de Paula, A.M.; Coimbra, C.C.; Santos, S.H. Resveratrol increases brown adipose tissue thermogenesis markers by increasing SIRT1 and energy expenditure and decreasing fat accumulation in adipose tissue of mice fed a standard diet. Eur. J. Nutr. 2014, 53, 1503–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Jiang, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, G.; Yin, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Yu, Z. Resveratrol reduces the inflammatory response in adipose tissue and improves adipose insulin signaling in high-fat diet-fed mice. Peer J. 2018, 6, 5173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Ma, M.; Lu, Y.; Wang, L.; Wu, C.; Duan, H. Rhaponticin from rhubarb rhizomes alleviates liver steatosis and improves blood glucose and lipid profiles in KK/Ay diabetic mice. Planta Med. 2009, 75, 472–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, S.P.; Kim, J.K.; Lim, Y.H. Antihyperlipidemic effects of rhapontin and rhapontigenin from Rheum undulatum in rats fed a high-cholesterol diet. Planta Med. 2014, 80, 1067–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, I.; Seki, T.; Noguchi, H.; Kashiwada, Y. Galloyl esters from rhubarb are potent inhibitors of squalene epoxidase, a key enzyme in cholesterol biosynthesis. Planta Med. 2000, 66, 753–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.-D.; Duan, Y.-Q.; Gao, J.-M.; Ruan, Z.-G. Screening for anti-lipase properties of 37 traditional Chinese medicinal herbs. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2020, 73, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.Y.; Seo, S.G.; Heo, Y.S.; Yue, S.; Cheng, J.-X.; Lee, K.W.; Kim, K.-H. Piceatannol, natural polyphenolic stilbene, inhibits adipogenesis via modulation of mitotic clonal expansion and insulin receptor-dependent insulin signaling in early phase of differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 11566–11578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mongioì, L.M.; La Vignera, S.; Cannarella, R.; Cimino, L.; Compagnone, M.; Condorelli, R.A.; Calogero, A.E. The role of resveratrol administration in human obesity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Yoon, G.; Hwang, Y.R.; Kim, Y.K.; Kim, S.N. Anti-obesity and hypolipidemic effects of Rheum undulatum in high-fat diet-fed C57BL/6 mice through protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B inhibition. BMB Rep. 2012, 45, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Kang, H.; Wang, L.; Zhao, X.; He, L. Chrysophanol ameliorates high-fat diet-induced obesity and inflammation in neonatal rats. Pharmazie 2018, 73, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Wang, H.; Niu, J.; Chen, H.; Wang, M.; Yang, Z.; Wang, S.; Sun, X.; Shi, Y. Cholesterol-lowering effects of rhubarb free anthraquinones and their mechanism of action. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2024, 966, 176348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, T.; Li, Y.; Hanafusa, Y.; Yeh, Y.-S.; Maruki-Uchida, H.; Kawakami, S.; Sai, M.; Goto, T.; Ito, T.; Kawada, T. Piceatannol exhibits anti-inflammatory effects on macrophages interacting with adipocytes. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 5, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Régnier, M.; Rastelli, M.; Morissette, A.; Suriano, F.; Le Roy, T.; Pilon, G.; Delzenne, N.M.; Marette, A.; Van Hul, M.; Cani, P.D. Rhubarb supplementation prevents diet-induced obesity and diabetes in association with increased Akkermansia muciniphila in mice. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Régnier, M.; Van Hul, M.; Roumain, M.; Paquot, A.; de Wouters d’Oplinter, A.; Suriano, F.; Everard, A.; Delzenne, N.M.; Muccioli, G.G.; Cani, P.D. Inulin increases the beneficial effects of rhubarb supplementation on high-fat high-sugar diet-induced metabolic disorders in mice: Impact on energy expenditure, brown adipose tissue activity, and microbiota. Gut Microbes 2023, 5, 2178796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-F. Treatment with rhubarb improves brachial artery endothelial function in patients with atherosclerosis: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2007, 35, 583–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd, A.J.; Martinez-Martin, M.P.; Warren-Walker, A.; Hitchings, M.D.; Moron-Garcia, O.M.; Watson, A.; Villarreal-Ramos, B.; Lyons, L.; Wilson, T.; Allison, G.; et al. Green tea with rhubarb root reduces plasma lipids while preserving gut microbial stability in a healthy human cohort. Metabolites 2025, 15, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojaei-Shad, F.; Jahantigh-Haghighi, M.; Mansouri, A.; Jahantigh-Haghighi, M. The effect of rhubarb stem extract on blood pressure and weight of type 2 diabetic patients. Med. Sci. 2019, 23, 159–162. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, F.-j.; Tang, Y.-M.; Hu, B.-Y.; Yang, F.-N.; Jin, W.; Miao, Y.-F.; Lu, Y. Mechanistic insights into the multi-target anti-atherosclerotic actions of rhubarb: A traditional remedy revisited. Chin. Med. 2025, 20, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Feng, S.X.; Zhang, H.J.; Zhang, N.; Liu, X.F.; Wan, Y.; Zhou, Y.X.; Li, J.S. Pharmacokinetics, tissue distribution and excretion of five rhubarb anthraquinones in rats after oral administration of effective fraction of anthraquinones from Rheum officinale. Xenobiotica 2021, 51, 916–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Sun, M.; Xing, J.; Corke, H. Antioxidant phenolic constituents in roots of Rheum officinale and Rubia cordifolia: Structure-radical scavenging activity relationships. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 7884–7890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.S.; Chen, F.; Liu, X.H.; Xu, H.; Zhou, Y.Z. Progress in research of chemical constituents and pharmacological actions of rhubarb. Chin. J. New Drugs 2011, 20, 1534–1548. [Google Scholar]

- Karaś, M.; Jakubczyk, A.; Szymanowska, U.; Złotek, U.; Zielińska, E. Digestion and bioavailability of bioactive phytochemicals. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 52, 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahidi, F.; Ramakrishnan, V.V.; Oh, W.Y. Bioavailability and metabolism of food bioactives and their health effects: A review. J. Food Bioact. 2019, 8, 6–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Wang, C.L.; Fan, B.L. Advances in research on target organ of rhubarb and its specific toxicity. J. Toxicol. 2015, 29, 461–464. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Qu, L.; He, Y.; Routledge, M.N.; Yun Gong, Y.; Qiao, B. Identification of rhein as the metabolite responsible for toxicity of rhubarb anthraquinones. Food Chem. 2020, 331, 127363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, C.; Niu, M.; Li, C.; Liu, X.; He, Q.; Li, R.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, X.; Wang, J. Network pharmacology oriented study reveals inflammatory state-dependent dietary supplement hepatotoxicity responses in normal and diseased rats. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 3477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehman, H.; Begum, W.; Anjum, F.; Tabasum, H. Rheum emodi (rhubarb): A fascinating herb. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2014, 3, 89–94. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, H.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, T.; Wu, X.; Li, C.; Yang, H.J.; Jeong, D.Y.; Park, S. Fermented rhubarb alleviates metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease symptoms by modulating gut microbiota and activating the hepatic insulin signaling pathway. Food Biosci. 2025, 63, 105720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.C.; Li, G.W.; Wang, T.T.; Gao, L.; Wang, F.F.; Shang, H.W.; Yang, Z.J.; Guo, Y.X.; Wang, B.Y.; Xu, J.D. Rhubarb extract relieves constipation by stimulating mucus production in the colon and altering the intestinal flora. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 138, 111479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; He, C.; Hua, R.; Liang, C.; Wang, B.; Du, Y.; Xin, S.; Guo, Y.; Gao, L.; Zhang, L.; et al. Underlying beneficial effects of rhubarb on constipation-induced inflammation, disorder of gut microbiome and metabolism. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1048134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Cao, X.; Miao, X.; Yang, X.; Zhang, J.; Shang, X. The chemical composition, protective effect of Rheum officinale leaf juice and its mechanism against dextran sulfate sodium-induced ulcerative colitis. Phytomedicine 2024, 129, 155653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ye, Z.; He, H.; Hu, Y.; Wu, M.; Li, L.; Chen, L.; Qian, H.; Shi, Q.; Zhang, C.; et al. The application of Tong-fu therapeutic method on ulcerative colitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis for efficacy and safety of rhubarb-based therapy. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1036593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.E.; Niu, M.; Li, R.Y.; Feng, W.W.; Ma, X.; Dong, Q.; Ma, Z.J.; Li, G.Q.; Meng, Y.K.; Wang, Y.; et al. Untargeted metabolomics reveals dose-response characteristics for effect of rhubarb in a rat model of cholestasis. Front. Pharmacol. 2016, 7, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Z.; Fei, J.; Wenjian, X.; Jiachen, J.; Beina, J.; Zhonghua, C.; Xiangyi, Y.; Shaoying, W. Rhubarb attenuates the severity of acute necrotizing pancreatitis by inhibiting MAPKs in rats. Immunotherapy 2012, 4, 1817–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Zhu, S.; Li, J.; Long, D.; Wan, M.; Tang, W. Epigenetic changes in inflammatory genes and the protective effect of cooked rhubarb on pancreatic tissue of rats with chronic alcohol exposure. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 146, 112587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyrinck, A.M.; Etxeberria, U.; Taminiau, B.; Daube, G.; Van Hul, M.; Everard, A.; Cani, P.D.; Bindels, L.B.; Delzenne, N.M. Rhubarb extract prevents hepatic inflammation induced by acute alcohol intake, an effect related to the modulation of the gut microbiota. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61, 1500899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, B.; Fu, H.; Yin, J.; Xu, F. Efficacy of rhubarb combined with early enteral nutrition for the treatment of severe acute pancreatitis: A randomized controlled trial. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 49, 1375–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yang, K.; Jing, G.; Yang, J.; Li, K. Meta-analysis of efficacy of rhubarb combined with early enteral nutrition for the treatment of severe acute pancreatitis. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2020, 44, 1066–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzaal, M.; Saeed, F.; Shah, Y.A.; Hussain, M.; Rabail, R.; Socol, C.T.; Hassoun, A.; Pateiro, M.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Rusu, A.V.; et al. Human gut microbiota in health and disease: Unveiling the relationship. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 999001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, K.; Wu, Z.X.; Chen, X.Y.; Wang, J.Q.; Zhang, D.; Xiao, C.; Zhu, D.; Koya, J.B.; Wei, L.; Li, J.; et al. Microbiota in health and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, S.; Zolghadri, S.; Stanek, A. Beneficial effects of anti-inflammatory diet in modulating gut microbiota and controlling obesity. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Wu, J.; Wang, M.; Zhou, C.; Zhong, R.; Tan, Z. Rhubarb supplementation promotes intestinal mucosal innate immune homeostasis through modulating intestinal epithelial microbiota in goat kids. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 1047–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Hu, B.; Ye, C.; Zhang, Z.; Yin, M.; Cao, Q.; Ba, Y.; Liu, H. Stewed rhubarb decoction ameliorates adenine-induced chronic renal failure in mice by regulating gut microbiota dysbiosis. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 842720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Liu, T.; Pan, F.; Ao, X.; Wang, L.; Liang, R.; Lei, Y.; Ding, Y.; Yu, M.; Li, L.; et al. Rhubarb with different cooking methods restored the gut microbiota dysbiosis and SCFAs in ischemic stroke mice. Mol. Neurobiol. 2025, 62, 10228–10244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Cao, D.; Ao, W.; Li, T.; Xian, M.; Wang, S. Therapeutic effects of raw rhubarb on gastrointestinal complications in ischemic stroke: An integrated analysis of gut microbiota, metabolomics, and network pharmacology. J. Holist. Integr. Pharm. 2025, 6, 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Tan, L.F.; Shen, L.; Kuang, J.-H.; Zhan, S.-K.; Liu, B.; Cai, J.-L.; Ling, S.-W.; Xian, M.-H.; Wang, S.-M. Integrated gut microbiota, plasma metabolomics and network pharmacology to reveal the anti-ischemic stroke effect of cooked rhubarb. Tradit. Med. Res. 2024, 9, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Hu, J.; Liu, Z.; Ma, Y.; Xu, W.; Wang, W.; Gao, J.; Wang, T. The water extract of rhubarb prevents ischemic stroke by regulating gut bacteria and metabolic pathways. Metabolites 2024, 14, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, M.; Ma, Z.; Zhan, S.; Shen, L.; Li, T.; Lin, H.; Huang, M.; Cai, J.; Hu, T.; Liang, J.; et al. Network analysis of microbiome and metabolome to explore the mechanism of raw rhubarb in the protection against ischemic stroke via microbiota-gut-brain axis. Fitoterapia 2024, 175, 105969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, L.; Wang, J.; Guo, Y. Polysaccharides influence human health via microbiota-dependent and -independent pathways. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1030063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Luo, J.; Liu, Y.; Yu, S.; Liu, J. Rheum tanguticum polysaccharide alleviates DSS-induced ulcerative colitis and regulates intestinal microbiota in mice. Food Biosci. 2023, 53, 102788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Shi, L.; Li, Y.; Mu, W.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, W.; Qi, Y.; Liu, L. Polysaccharides extracted from Rheum tanguticum ameliorate radiation-induced enteritis via activation of Nrf2/HO-1. J. Radiat. Res. 2021, 62, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Feng, Q.; Li, Y.; Lin, Y.; Yao, J.; Jia, Z.; Lu, L.; Liu, L.; Zhou, H. Integrated network pharmacology and DSS-induced colitis model to determine the anti-colitis effect of Rheum palmatum L. and Coptis chinensis Franch in granules. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2023, 300, 115675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Liu, H.; Wang, E.; Tang, F. Effect of rhubarb polysaccharide combined with semen crotonis pulveratum on intestinal lymphocyte homing in rats with TNBS-induced colitis. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2018, 11, 13308–13318. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y.; Wu, C.; Chen, H.; Zheng, T.; Ye, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, J.; Li, Y.; Dong, Z. Rhubarb polysaccharide and berberine co-assembled nanoparticles ameliorate ulcerative colitis by regulating the intestinal flora. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1184183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.Y.; Zheng, Z.L.; Chen, C.W.; Lu, B.W.; Liu, D. Targeting gut microbiota with natural polysaccharides: Effective interventions against high-fat diet-induced metabolic diseases. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 859206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Q.; Li, Y.; Dai, X.; Wang, B.; Zhang, J.; Cao, H. Polysaccharides: The potential prebiotics for metabolic associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD). Nutrients 2023, 15, 3722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, J.; Xu, F.; Wei, H.; Gao, Y.; Liu, N.; Zhao, J.; Yu, Z.; Chen, L.; Dou, X. Metabolic restoration: Rhubarb polysaccharides as a shield against non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 305, 141151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, H.; Wang, K.-E.; Li, P.; Zhao, Y.-Y. Rhubarb: Traditional uses, phytochemistry, multiomics-based novel pharmacological and toxicological mechanisms. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2025, 19, 9457–9480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanati, K.; Oskoei, V.; Rezvani-Ghalhari, M.; Shavali-Gilani, P.; Mirzaei, G.; Sadighara, P. Oxalate in plants, amount and methods to reduce exposure; a systematic review. Toxin Rev. 2024, 43, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Pro-Inflammatory Factors | Examples | Activities That May be Particularly Relevant for Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Food Components |

|---|---|---|

| physical and chemical factors, including environmental pollutants | ultraviolet and ionizing radiation, xenobiotics (including pesticides), heavy metals, endocrine disruptors, allergens | different mechanisms of antioxidant action, incl. scavenging of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, stimulation of the antioxidant enzyme-mediated protection, transition, and heavy metal ion chelation; suppression of pro-inflammatory response at the molecular and cellular level, toxin-binding ability of dietary fiber |

| pathogens and other biological factors | infections, microbiome dysbiosis | antibacterial, antiviral, or antifungal action; immunomodulatory activity; the physiological microbiome-supporting properties |

| lifestyle-related | sedentary lifestyle, alcohol, smoking, unbalanced diet, consumption of highly processed and high-calorie foods, chronic stress | antioxidant properties; detoxifying effects; metabolism-modulatory properties and anti-obesity action; cardioprotective and hepatoprotective actions |

| diseases | obesity, insulin resistance, diabetes, and other chronic metabolic disorders, autoimmune diseases | antioxidant properties; suppression of pro-inflammatory response at the molecular and cellular level; metabolism-modulatory properties and anti-obesity action; cardioprotective action |

| Species | Plant Organ and/or Type of Preparation | Ethnomedicinal Recommendations | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| R. acuminatum Hook.f. & Thomson | leaves and petioles | diarrhea, headaches, constipation; traditional food: as a vegetable or used to prepare pickles | [15] |

| R. australe D.Don. | root powder or roots in different formulations | cough and rhinitis, hemoptysis, as a laxative, tonic, and diuretic to improve wound healing | [16] |

| pounded fruit | herpes infection | [17] | |

| R. emodi Wall. | roots paste mixed with turmeric powder and mustard oil | rheumatism, muscular pain | [18] |

| root decoction mixed with oil | burns | [19] | |

| R. maximowiczii Losinsk. | roots-based preparations | intestinal disorders, constipation, or diarrhea | [20] |

| crushed leaves and petioles | wounds | [20] | |

| R. officinale Baill. | roots in different formulations | gastrointestinal disorders, blood purification, detoxification, fever, removing blood stasis, promoting menstruation | [21] |

| chronic renal failure | [22] | ||

| cancer | [23] | ||

| R. palmatum L. | root-based preparations | constipation, gastritis, hepatitis, gastric ulcer, enteritis, diabetes, inflammation, atherosclerosis, cancer | [24] |

| R. rhabarbarum L. | root-based preparations | liver, spleen, and stomach dysfunctions blood purification, bleeding, fever, injuries, and trauma | [25] |

| roots in different formulations | a natural anti-inflammatory agent for appendicitis, cholecystitis, and rheumatoid arthritis therapy | [26] | |

| R. rhaponticum L. | roots in wine, beer, or mead | gastrointestinal pain, gastritis, liver and spleen disorders, heartache and pain in pericardium, pulmonary system dysfunctions, reproductive system disorders, uterine, and breast pain | [25] |

| roots boiled in red wine and sweetened with honey | to improve voice | [27] | |

| sugar syrup | fever | [27] | |

| a brandy-based balsam | heart problems or stomachache | [27] | |

| underground parts | ingredient of the Mesir paste—a traditional Turkish folk food and remedy, used to treat infectious diseases and to stimulate the immune system | [28] | |

| R. tanguticum Maxim. ex Balf. | dried root powder | purgative | [29] |

| R. tibeticum Maxim. ex Hook.f. | roots | expectorant, injuries, ulcers, skin ailments | [30] |

| boiled leaves | laxative | [30] |

| Rhubarb Species | Type of Extract | Experimental System | Main Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R. palmatum | stem extract | RAW 264.7 cells | ↓ NO, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α | [44] |

| R. rhaponticum | root extract | PBMCs | ↓ TNF and IL-2 release | [88] |

| HUVECs | no changes in COX-2 gene expression ↓ 5-LOX gene expression ↓ monocyte adhesion to endothelial cells | [79] | ||

| THP1-ASC-GFP monocytes | ↓ inflammasome activation | [88] | ||

| petiole extract | PBMCs | ↓ TNF and IL-2 release | [88] | |

| HUVECs | ↓ COX-2 gene expression ↓ 5-LOX gene expression | [79] | ||

| THP1-ASC-GFP monocytes | ↓ inflammasome activation | [88] | ||

| R. rhabarbarum | root extract | PBMCs | ↓ IL-2 release | [88] |

| HUVECs | no changes in COX-2 gene expression no changes in 5-LOX gene expression ↓ monocyte adhesion to EC | [79] | ||

| rhizome extract | HUVECs | ↓ TNF-induced activation of NF-κB-p65 ↓ expression of adhesion molecules (ICAM-1 and VCAM-1) ↓ the monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) | [92] | |

| THP1-ASC-GFP monocytes | ↓ inflammasome activation | [88] | ||

| RAW 264.7 macrophages | ↓ inflammatory activation, incl. generation of NO | [93] | ||

| petiole extract | PBMCs | ↓ TNF and IL-2 release | [88] | |

| HUVECs | ↓ COX-2 gene expression ↓ 5-LOX gene expression | [79] | ||

| THP1-ASC-GFP monocytes | ↓ inflammasome activation | [88] | ||

| RAW 264.7 macrophages | ↓ inflammatory activation, incl. generation of NO | [93] | ||

| leaf extracts | RAW 264.7 macrophages | ↓ inflammatory activation, incl. generation of NO | [93] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kolodziejczyk-Czepas, J.; Czepas, J. Rhubarb as a Potential Component of an Anti-Inflammatory Diet. Foods 2025, 14, 4219. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244219

Kolodziejczyk-Czepas J, Czepas J. Rhubarb as a Potential Component of an Anti-Inflammatory Diet. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4219. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244219

Chicago/Turabian StyleKolodziejczyk-Czepas, Joanna, and Jan Czepas. 2025. "Rhubarb as a Potential Component of an Anti-Inflammatory Diet" Foods 14, no. 24: 4219. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244219

APA StyleKolodziejczyk-Czepas, J., & Czepas, J. (2025). Rhubarb as a Potential Component of an Anti-Inflammatory Diet. Foods, 14(24), 4219. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244219