A Time-Resolved Fluorescent Lateral Flow Immunoassay for the Rapid and Ultra-Sensitive Detection of AFB1 in Peanuts and Maize

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Equipment

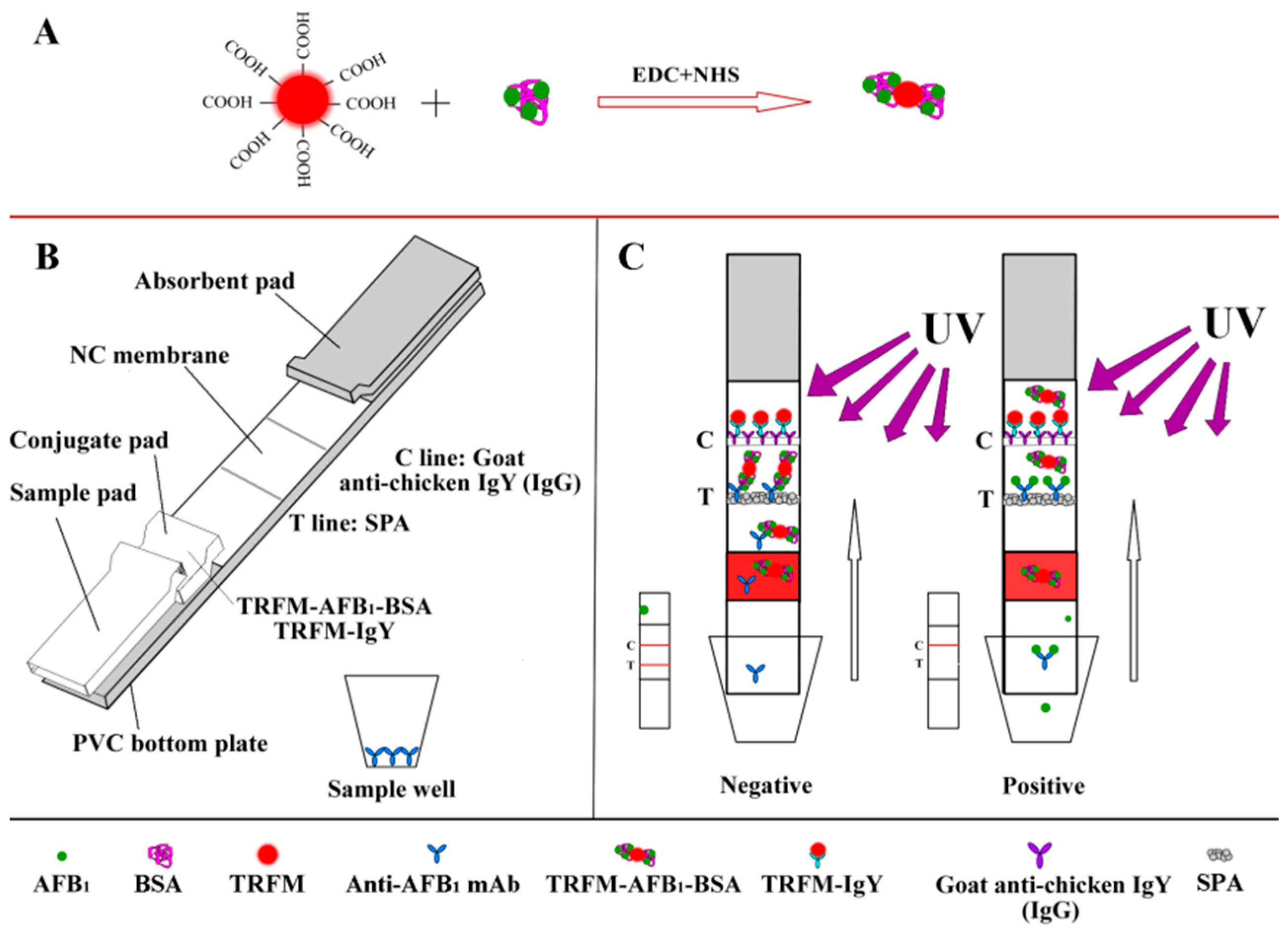

2.2. Preparation of TRFM Probes

2.3. Preparation of the TRFN-LFIA

2.4. Detection Principle of the TRFN-LFIA

2.5. Sample Preparation

2.6. Assay Procedure

2.7. Evaluation of Sensitivity

2.8. Evaluation of Specificity

2.9. Evaluation of Accuracy and Precision

2.10. Analysis of Naturally Contaminated Samples

2.11. Comparison and Analysis of Different Detection Modes

3. Results

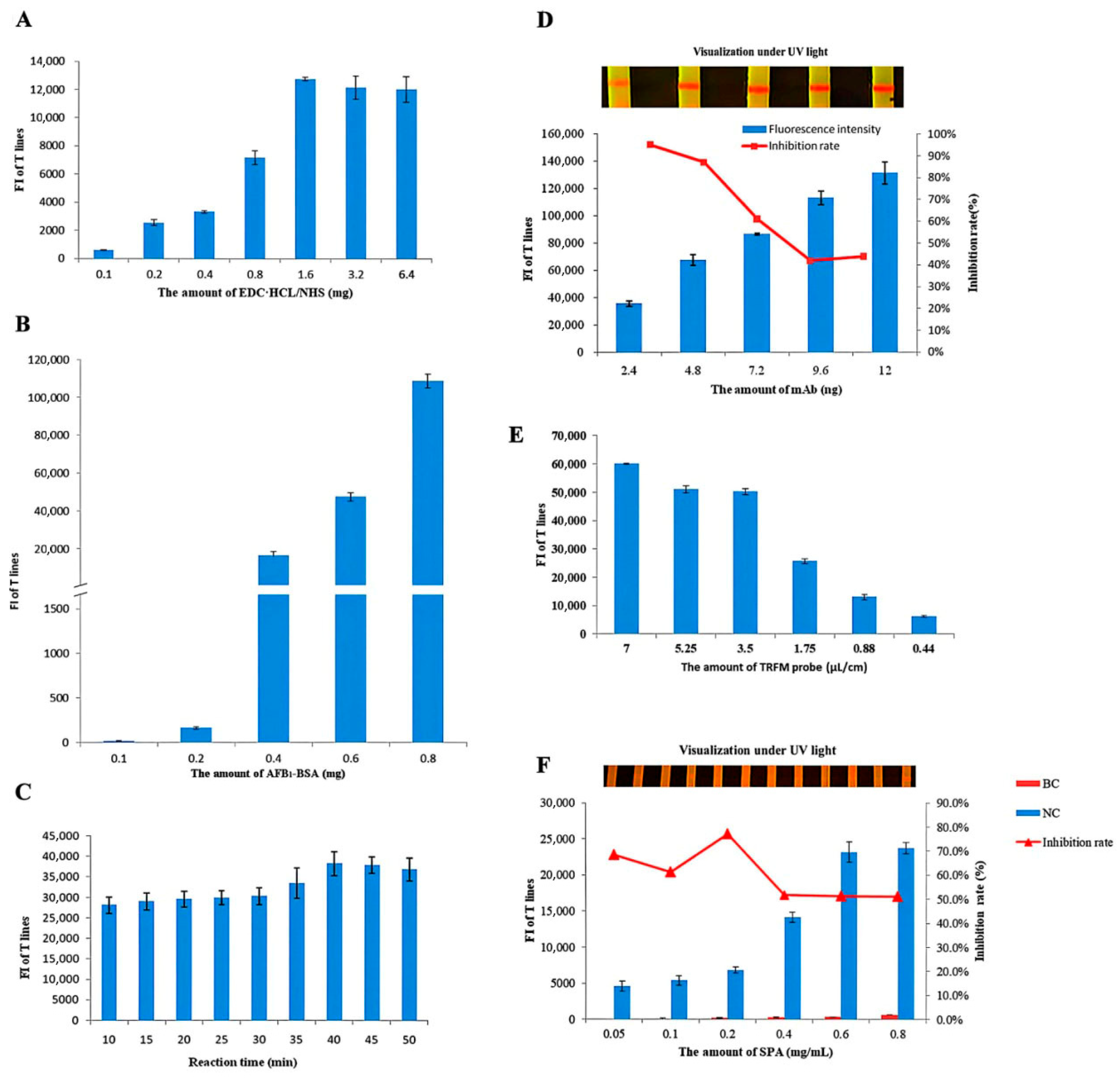

3.1. Optimization of TRFN-LFIA

3.1.1. Optimization of the Labeling of Probe

3.1.2. Optimization of the TRFN-LFIA Reaction Time

3.1.3. Optimization of Anti-AFB1 mAb Amount

3.1.4. Optimization of TRFM Probe Amount

3.1.5. Optimization of the Concentration of SPA

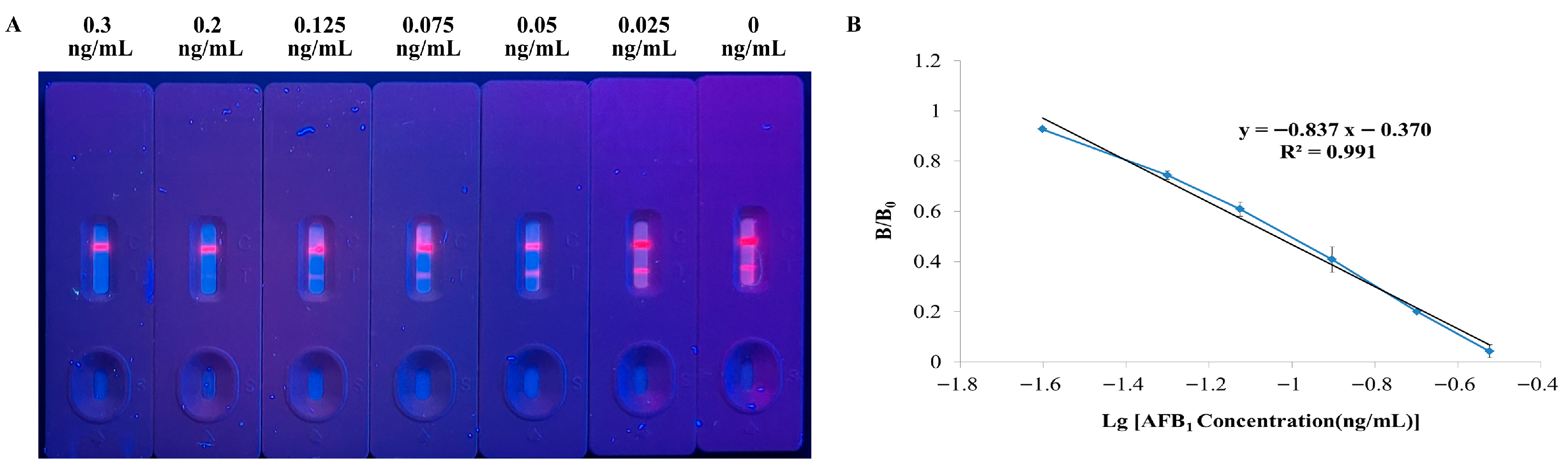

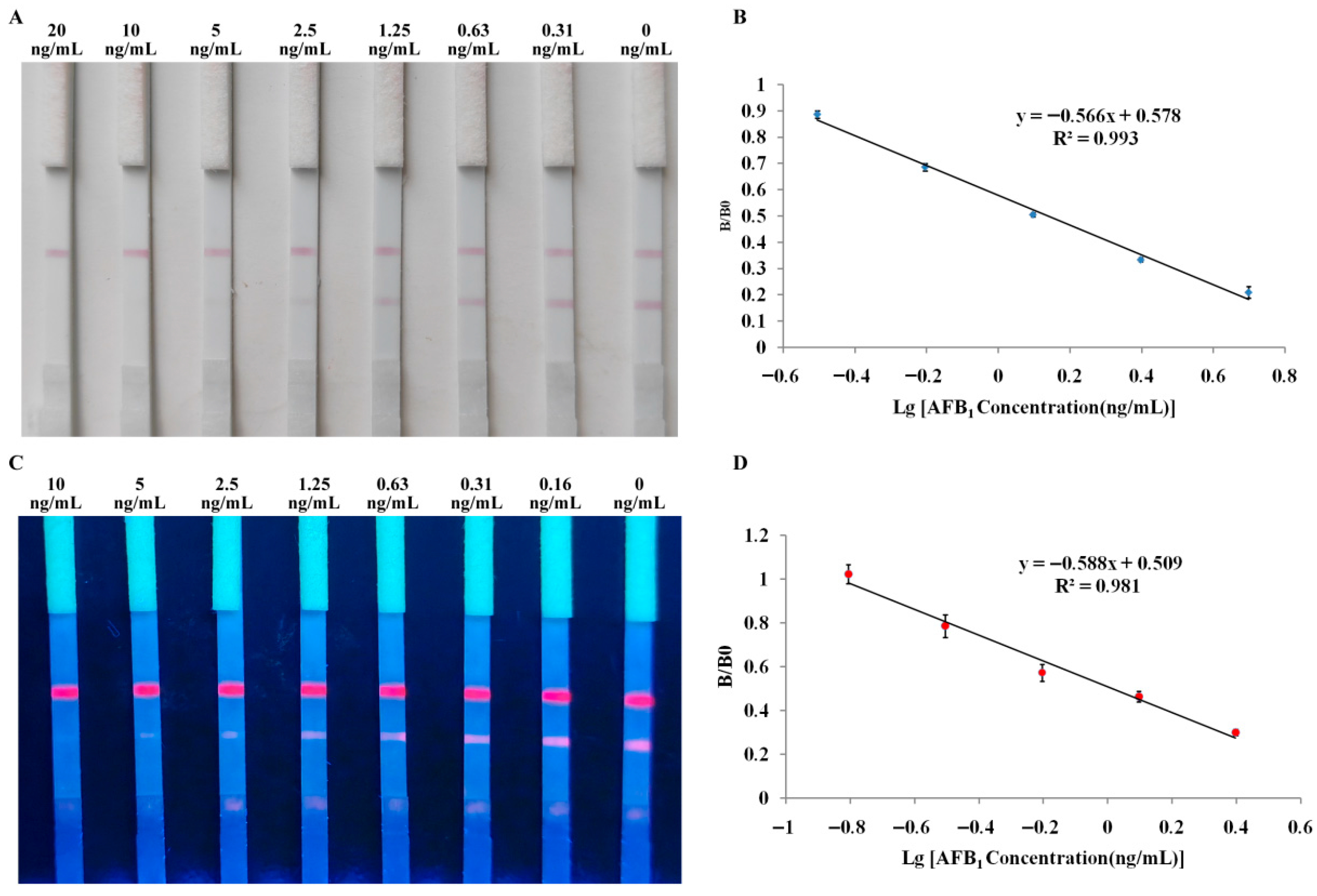

3.2. Sensitivity

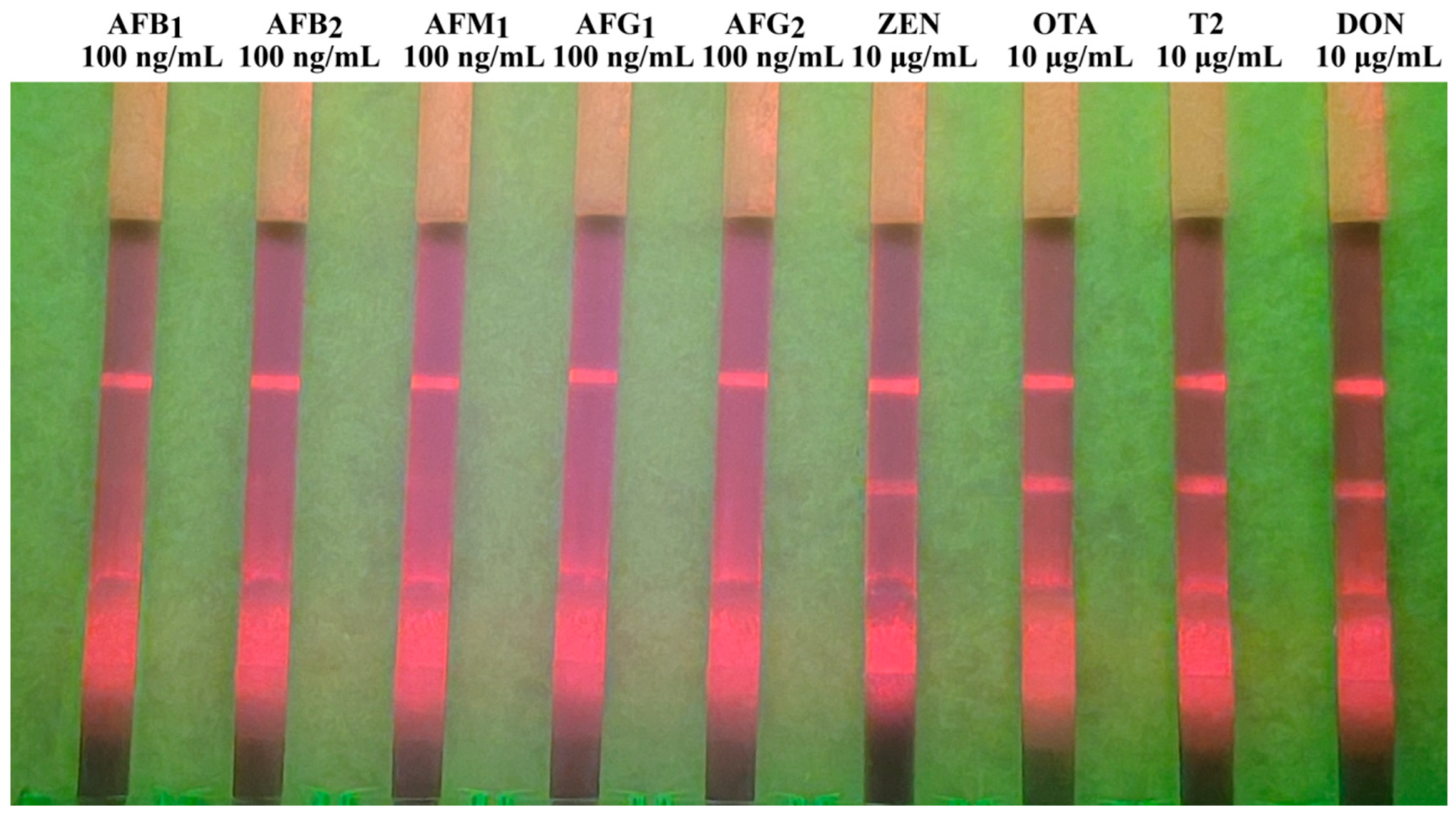

3.3. Specificity

3.4. Accuracy and Precision

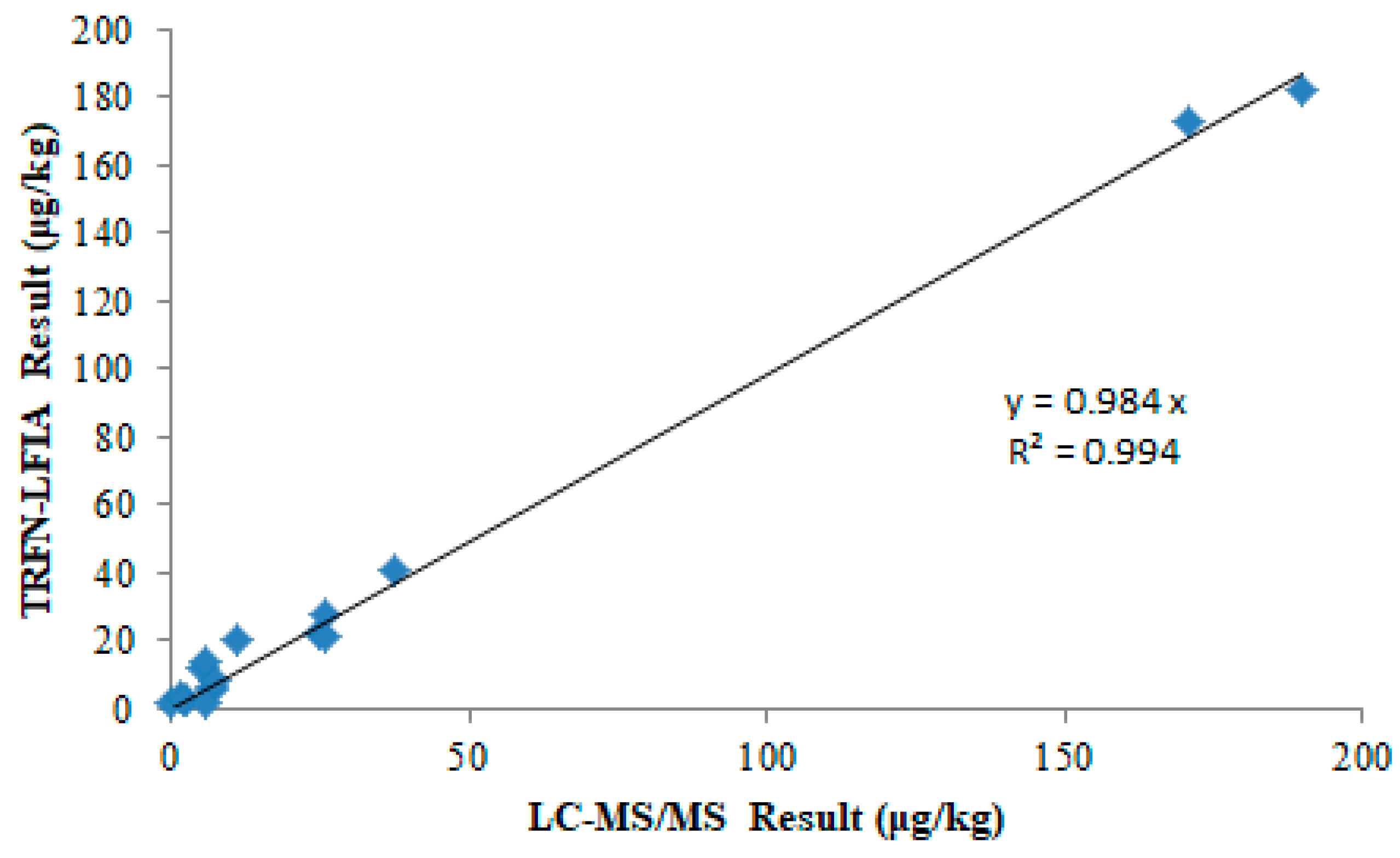

3.5. Analysis Results of Naturally Contaminated Samples

3.6. Comparison Results of Different Detection Modes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, X.; Wang, D.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, M.; Yang, Q.; Dong, J.; Zhang, Q.; Feng, P. Research Progress Related to Aflatoxin Contamination and Prevention and Control of Soils. Toxins 2023, 15, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.; Tian, E.; Hao, Z.; Tang, S.; Wang, Z.; Sharma, G.; Jiang, H.; Shen, J. Aflatoxin B1 Toxicity and Protective Effects of Curcumin: Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Implications. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Tang, S.; Peng, X.; Sharma, G.; Yin, S.; Hao, Z.; Li, J.; Shen, J.; Dai, C. Lycopene as a Therapeutic Agent against Aflatoxin B1-Related Toxicity: Mechanistic Insights and Future Directions. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gourd, E. High concentrations of aflatoxin in Ugandan grains sparks public health concern. Lancet Oncol. 2023, 24, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, S.; Kortei, N.K.; Sackey, M.; Richard, S.A. Aflatoxin B1 induces infertility, fetal deformities, and potential therapies. Open Med. 2024, 19, 20240907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lalah, J.; Omwoma, S.; Orony, D.A.O. Aflatoxin B1: Chemistry, Environmental and Diet Sources and Potential Exposure in Human in Kenya. In Aflatoxin B1 Occurrence, Detection and Toxicological Effects; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, A.; Tan, L.; Tan, S.; Wang, G.; Qiu, W. The Temporal Dynamics of Sensitivity, Aflatoxin Production, and Oxidative Stress of Aspergillus flavus in Response to Cinnamaldehyde Vapor. Foods 2023, 12, 4311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souto, N.S.; Claudia, M.B.A.; Lutchemeyer, D.F.M.; Rechia, F.M.; Royes, L.; Schneider, O.M.; Furian, A.F. Aflatoxin B1 reduces non-enzymatic antioxidant defenses and increases protein kinase C activation in the cerebral cortex of young rats. Nutr. Neurosci. 2018, 21, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, E.; Chandra, P. Aflatoxins: Food Safety, Human Health Hazards and Their Prevention; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, F.A.Z.; Abdel-Maksoud, F.M.; Abd Elaziz, H.O.; Al-Brakati, A.; Elmahallawy, E.K. Descriptive Histopathological and Ultrastructural Study of Hepatocellular Alterations Induced by Aflatoxin B1 in Rats. Animals 2021, 11, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, W. Aflatoxin B1 impairs mitochondrial functions, activates ROS generation, induces apoptosis and involves Nrf2 signal pathway in primary broiler hepatocytes. Anim. Sci. J. 2016, 87, 1490–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; He, Y.; Tian, J.; Muhammad, I.; Liu, M.; Wu, C.; Xu, C.; Zhang, X. Ferulic acid prevents aflatoxin B1-induced liver injury in rats via inhibiting cytochrome P450 enzyme, activating Nrf2/GST pathway and regulating mitochondrial pathway. Ecotox. Environ. Safe. 2021, 224, 112624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Wang, T.; Nepovimova, E.; Long, M.; Wu, W.; Kuca, K. Progress on the detoxification of aflatoxin B1 using natural anti-oxidants. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2022, 169, 113417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Sun, M.; He, Y.; Lei, J.; Han, Y.; Wu, Y.; Bai, D.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, B. Mycotoxins binder supplementation alleviates aflatoxin B1 toxic effects on the immune response and intestinal barrier function in broilers. Poult. Sci. 2022, 101, 101683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, J.; Yuan, Q.; Yan, H.; Tian, G.; Chen, D.; He, J.; Zheng, P.; Yu, J.; Mao, X.; Huang, Z.; et al. Effects of Chronic Exposure to Low Levels of Dietary Aflatoxin B1 on Growth Performance, Apparent Total Tract Digestibility and Intestinal Health in Pigs. Animals 2021, 11, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahey, N.G.; Abd, E.H.; Gadalla, K.K. Toxic effect of aflatoxin B1 and the role of recovery on the rat cerebral cortex and hippocampus. Tissue Cell 2015, 47, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, X.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, H.; Liu, D.; Liu, X.; Li, L.; Li, C.; Xiao, X.; Tang, S.; Li, D. Food-Origin Mycotoxin-Induced Neurotoxicity: Intend to Break the Rules of Neuroglia Cells. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 9967334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Xing, L.; Zhang, M.; Wang, J.; Zheng, N. The Toxic Effects of Aflatoxin B1 and Aflatoxin M1 on Kidney through Regulating L-Proline and Downstream Apoptosis. Biomed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 9074861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frangiamone, M.; Lozano, M.; Cimbalo, A.; Font, G.; Manyes, L. AFB1 and OTA Promote Immune Toxicity in Human LymphoBlastic T Cells at Transcriptomic Level. Foods. 2023, 12, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Huang, K.; Long, M.; Yang, S.; Zhang, Y. An update on immunotoxicity and mechanisms of action of six environmental mycotoxins. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2022, 163, 112895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rushing, B.R.; Selim, M.I. Aflatoxin B1: A review on metabolism, toxicity, occurrence in food, occupational exposure, and detoxification methods. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 124, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchese, S.; Polo, A.; Ariano, A.; Velotto, S.; Costantini, S.; Severino, L. Aflatoxin B1 and M1: Biological Properties and Their Involvement in Cancer Development. Toxins 2018, 10, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostry, V.; Malir, F.; Toman, J.; Grosse, Y. Mycotoxins as human carcinogens-the IARC Monographs classification. Mycotoxin Res. 2017, 33, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Fotina, H.; Wang, Z. A Novel Lateral Flow Immunochromatographic Assay for Rapid and Simultaneous Detection of Aflatoxin B1 and Zearalenone in Food and Feed Samples Based on Highly Sensitive and Specific Monoclonal Antibodies. Toxins 2022, 14, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB2761-2017; National standard of People’s Republic of China, Food Safety China National Standard, Limit of Mycotoxins in Food. Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2017; p. 8.

- GB13078-2017; National Standard of People’s Republic of China. Hygienical Standard for Feeds. Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2017; p. 7.

- 165/2010; European Union Commission Regulation. The European Commission: Brussels, Belguim, 2010.

- Zhu, F.; Zhang, B.; Zhu, L. An up-converting phosphor technology-based lateral flow assay for rapid detection of major mycotoxins in feed: Comparison with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. PLoS ONE. 2021, 16, e0250250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F. No. P-15025/264/13-PA/FSSAI; Food Safety and Standards (Contaminants, Toxins, and Residues) Regulations. Food Safety and Standards Authority of India: New Delhi, India, 2015.

- Ali, N. Aflatoxins in rice: Worldwide occurrence and public health perspectives. Toxicol Rep. 2019, 6, 1188–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kai, Z.; Kaushik, B. A Review: Sample Preparation and Chromatographic Technologies for Detection of Aflatoxins in Foods. Toxins 2020, 12, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; WU, J.; Pei, Y.; Chen, X.; Sun, Y.; Hu, M.; Xing, Y.; Cao, J.; Li, Z.; et al. Development of an immunochromatographic strip test for the rapid detection of soybean Bowman-Birk inhibitor. Food Agric. Immunol. 2019, 30, 1202–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Sun, Y.; Xing, Y.; Fan, L.; Li, Y.; Shang, Y.; Chai, S.; Liu, Y. Development of a time-resolved fluorescence immunochromatographic strip for gB antibody detection of PRV. BMC Vet. Res. 2025, 21, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, D.; Tang, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Q.; Li, P. Time-Resolved Fluorescence Immunochromatography Assay (TRFICA) for Aflatoxin: Aiming at Increasing Strip Method Sensitivity. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Wu, X.; Lu, Z.; Tao, X. Comparative Study of Time-Resolved Fluorescent Nanobeads, Quantum Dot Nanobeads and Quantum Dots as Labels in Fluorescence Immunochromatography for Detection of Aflatoxin B1 in Grains. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Zheng, Y.; Shao, H.; Xiao, M.; Sun, J.; Jin, M.; Jin, F.; Wang, J.; Abd El-Aty, A.M.; She, Y. Development of a time-resolved fluorescence microsphere Eu lateral flow test strip based on a molecularly imprinted electrospun nanofiber membrane for determination of fenvalerate in vegetables. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 957745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Hua, Q.; Wang, J.; Liang, Z.; Li, J.; Wu, J.; Shen, X.; Lei, H.; Li, X. A smartphone-based dual detection mode device integrated with two lateral flow immunoassays for multiplex mycotoxins in cereals. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020, 158, 112178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantwell, H. (Ed.) Eurachem Guide: The Fitness for Purpose of Analytical Methods—A Laboratory Guide to Method Validation and Related Topics, 3rd ed.; Eurachem: Teddington, UK, 2025; Available online: https://www.eurachem.org/index.php/publications/guides/mv?tmpl=component&print=1 (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Zhang, M.Z.; Wang, M.Z.; Chen, Z.L.; Fang, J.H.; Fang, M.M.; Liu, J.; Yu, X.P. Development of a colloidal gold-based lateral-flow immunoassay for the rapid simultaneous detection of clenbuterol and ractopamine in swine urine. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2009, 395, 2591–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, P.; Zhang, Q.; Li, R.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Ding, X.; Tang, X. Multi-component immunochromatographic assay for simultaneous detection of aflatoxin B1, ochratoxin A and zearalenone in agro-food. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2013, 49, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, L.; Song, S.; Sun, M.; Kuang, H.; Xu, C.; Guo, L. Colloidal gold immunochromatographic assay for the detection of total aflatoxins in cereals. Food Chem. 2025, 472, 142877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, J.; Gurmin, T.; Robinson, N. The place of gold in rapid tests. IVD Technol. 2000, 7, 37–49. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, N. Immunogold conjugation for IVD applications. IVD Technol. 2002, 8, 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Shim, W.B.; Kim, M.J.; Mun, H.; Kim, M.G. An aptamer-based dipstick assay for the rapid and simple detection of aflatoxin B1. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2014, 62, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, X.; Li, P.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, J. Time-Resolved Fluorescence Immunochromatographic Assay Developed Using Two Idiotypic Nanobodies for Rapid, Quantitative, and Simultaneous Detection of Aflatoxin and Zearalenone in Maize and Its Products. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 11520–11528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, Z.; Li, X.; Fan, Q.; Chen, Y.; Shi, G. “Green” Extraction and On-Site Rapid Detection of Aflatoxin B1, Zearalenone and Deoxynivalenol in Corn, Rice and Peanut. Molecules 2023, 28, 3260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Analogue | IC50 (ng/mL) | CR (%) |

|---|---|---|

| AFB1 | 0.09 | 100% |

| AFB2 | 19.16 | 0.48 |

| AFM1 | 2.54 | 3.58 |

| AFG1 | 1.52 | 5.97 |

| AFG2 | 3.96 | 2.30 |

| ZEN | >10,000 | <0.001 |

| OTA | >10,000 | <0.001 |

| T2 | >10,000 | <0.001 |

| DON | >10,000 | <0.001 |

| Sample | Spiked Level (µg/kg) | Detection Level (mean ± SD) (µg/kg) | Recovery (%) | CV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peanut | 1 | 1.04 ± 0.14 | 103.88 | 13.29 |

| 2 | 1.84 ± 0.13 | 91.81 | 6.99 | |

| 5 | 4.35 ± 0.40 | 86.91 | 9.10 | |

| 25 | 27.24 ± 2.75 | 108.97 | 10.09 | |

| Maize | 1 | 0.81 ± 0.11 | 81.33 | 13.04 |

| 2 | 2.36 ± 0.11 | 117.86 | 4.66 | |

| 5 | 5.52 ± 0.24 | 110.36 | 4.36 | |

| 25 | 24.65 ± 2.36 | 98.61 | 9.55 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xing, Y.; Yang, S.; Fan, L.; Hu, X.; Liu, S.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Y. A Time-Resolved Fluorescent Lateral Flow Immunoassay for the Rapid and Ultra-Sensitive Detection of AFB1 in Peanuts and Maize. Foods 2025, 14, 4218. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244218

Xing Y, Yang S, Fan L, Hu X, Liu S, Wang Y, Sun Y. A Time-Resolved Fluorescent Lateral Flow Immunoassay for the Rapid and Ultra-Sensitive Detection of AFB1 in Peanuts and Maize. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4218. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244218

Chicago/Turabian StyleXing, Yunrui, Suzhen Yang, Lu Fan, Xiaofei Hu, Shengnan Liu, Yao Wang, and Yaning Sun. 2025. "A Time-Resolved Fluorescent Lateral Flow Immunoassay for the Rapid and Ultra-Sensitive Detection of AFB1 in Peanuts and Maize" Foods 14, no. 24: 4218. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244218

APA StyleXing, Y., Yang, S., Fan, L., Hu, X., Liu, S., Wang, Y., & Sun, Y. (2025). A Time-Resolved Fluorescent Lateral Flow Immunoassay for the Rapid and Ultra-Sensitive Detection of AFB1 in Peanuts and Maize. Foods, 14(24), 4218. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244218