Development of Cereal Bars Enriched with Andean Grains and Patagonian Calafate (Berberis microphylla): Nutritional Composition, Phenolic Content, Antioxidant, Textural, and Sensory Evaluation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials and Formulation of Cereal Bars

2.2. Determination of Texture

2.3. Determination of Bioactive Compounds of the Cereal Bars

2.3.1. Preparation of Cereal Bars Extracts

2.3.2. Determination of Total Phenolic Compounds (TPC)

2.3.3. Determination of Antioxidant Capacity Measured Using DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity

2.4. Theoretical Estimation of Nutritional Composition

2.5. Sensory Analysis

Applied Affective Tests

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Texture Determination

3.2. Total Phenolic Compounds (TPC) of Cereal Bars

3.3. Determination of Antioxidant Capacity

3.4. Theoretical Nutritional Composition of Cereal Bars

3.4.1. Macronutrients

3.4.2. Micronutrients

3.5. Sensory Evaluation of Cereal Bars

3.5.1. Acceptance, Preference, and Purchase Intention

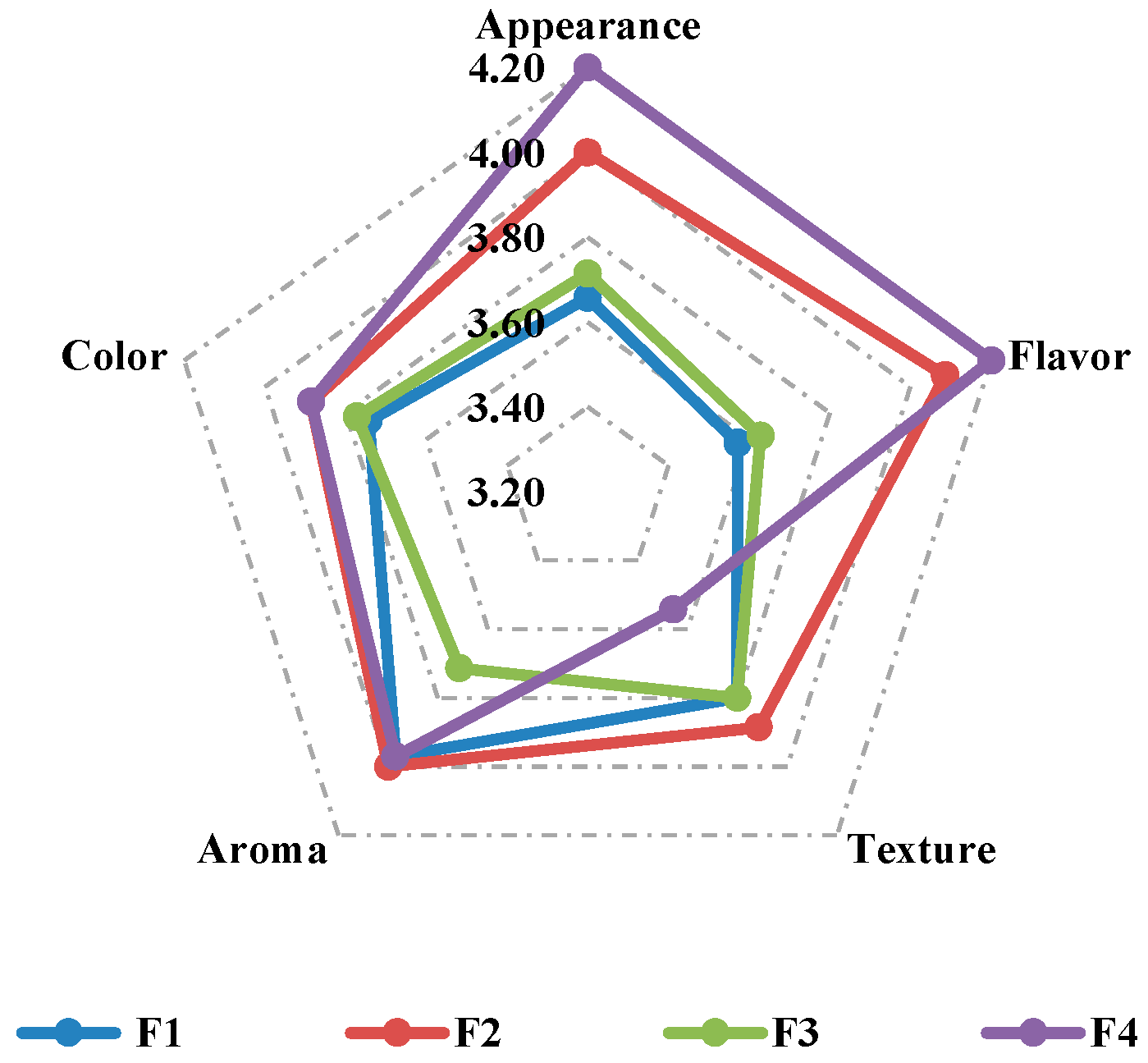

3.5.2. Sensory Attributes

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Olivares-Caro, L.; Radojkovic, C.; Chau, S.Y.; Nova, D.; Bustamante, L.; Neira, J.Y.; Perez, A.J.; Mardones, C. Berberis microphylla G. Forst (Calafate) Berry Extract Reduces Oxidative Stress and Lipid Peroxidation of Human LDL. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paredes Llosa, Y.C.; Velazquez Carlier, K.F.; Chasquibol, N. Development and Characterization of Andean Pseudocereal Bars Enriched with Native Collagen from Pota (Dosidicus gigas) By-Products. Biol. Life Sci. Forum 2024, 37, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estivi, L.; Pellegrino, L.; Hogenboom, J.A.; Brandolini, A.; Hidalgo, A. Antioxidants of Amaranth, Quinoa and Buckwheat Wholemeals and Heat-Damage Development in Pseudocereal-Enriched Einkorn Water Biscuits. Molecules 2022, 27, 7541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jan, N.; Hussain, S.Z.; Naseer, B.; Bhat, T.A. Amaranth and Quinoa as Potential Nutraceuticals: A Review of Anti-Nutritional Factors, Health Benefits and Their Applications in Food, Medicinal and Cosmetic Sectors. Food Chem. X 2023, 18, 100687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmos, E.; Roman-Garcia, I.; Reguera, M.; Mestanza, C.; Fernandez-Garcia, N. An Update on the Nutritional Profiles of Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.), Amaranth (Amaranthus spp.), and Chia (Salvia hispanica L.), Three Key Species with the Potential to Contribute to Food Security Worldwide. JSFA Rep. 2022, 2, 591–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghavami, A.; Banpouri, S.; Ziaei, R.; Talebi, S.; Vajdi, M.; Nattagh-Eshtivani, E.; Barghchi, H.; Mohammadi, H.; Askari, G. Effect of Soluble Fiber on Blood Pressure in Adults: A Systematic Review and Dose–Response Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutr. J. 2023, 22, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Qi, H.; Wang, P. Associations between Dietary Fiber Intake and Mortality from All Causes, Cardiovascular Disease and Cancer: A Prospective Study. J. Transl. Med. 2022, 20, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucena, B.S.; Burini, J.A.; Ordoñez, O.F.; Crespo, L.; Bruzone, M.C.; Mozzi, F.; Pescuma, M. Phenolic Compounds, Antioxidant Activity, Sensorial Analysis and Metabolic Syndrome Enzyme Inhibition Properties of Calafate (Berberis microphylla) Fruit Juice Fermented by Patagonian Lactic Acid Bacteria. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2025, 80, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, C.; Sánchez, R. Effect of Calafate (Berberis microphylla) Supplementation on Lipid Profile in Rats with Diet-Induced Obesity. Funct. Foods Health Dis. 2021, 11, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourekoua, H.; Djeghim, F.; Ayad, R.; Benabdelkader, A.; Bouakkaz, A.; Dziki, D.; Różyło, R. Development of Energy-Rich and Fiber-Rich Bars Based on Puffed and Non-Puffed Cereals. Processes 2023, 11, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eduardo, K.; Bedoya-Perales, N.; Escobedo-Pacheco, E.; Saldaña, E. Sensory and Consumer Science as a Valuable Tool to the Development of Quinoa-Based Food Products: More than Three Decades of Scientific Evidence. Sci. Agropecu. 2024, 15, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.; Schmidt, V.; Osen, R.; Bez, J.; Ortner, E.; Mittermaier, S. Texture, Sensory Properties and Functionality of Extruded Snacks from Pulses and Pseudocereal Proteins. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2022, 102, 5011–5021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rios, F.T.; Amaya, A.A.; Lobo, M.O.; Samman, N.C. Design and Acceptability of a Multi-Ingredients Snack Bar Employing Regional PRODUCTS with High Nutritional Value. Proceedings 2020, 53, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squeo, G.; Latrofa, V.; Vurro, F.; De Angelis, D.; Caponio, F.; Summo, C.; Pasqualone, A. Developing a Clean Labelled Snack Bar Rich in Protein and Fibre with Dry-Fractionated Defatted Durum Wheat Cake. Foods 2023, 12, 2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosicka-Gębska, M.; Sajdakowska, M.; Jeżewska-Zychowicz, M.; Gębski, J.; Gutkowska, K. Consumer Perception of Innovative Fruit and Cereal Bars-Current and Future Perspectives. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samakradhamrongthai, R.S.; Jannu, T.; Renaldi, G. Physicochemical Properties and Sensory Evaluation of High Energy Cereal Bar and Its Consumer Acceptability. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva Carvalho, V.; Conti-Silva, A.C. Storage Study of Cereal Bars Formulated with Banana Peel Flour: Bioactive Compounds and Texture Properties. Nutr. Food Sci. 2018, 48, 386–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Rossi, J.A. Colorimetry of Total Phenolics with Phodphomolybdic-Phosphotungstic Acid Reagents. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1965, 16, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, L.; Dias, L.G.; Pereira, J.A.; Estevinho, L. Antioxidant Properties, Total Phenols and Pollen Analysis of Propolis Samples from Portugal. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2008, 46, 3482–3485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacarías, I.; Barrios, L.; González, C.G.; Loeff, T.; Vera, G. Food Composition Table. Instituto de Nutrición y Tecnología de Los Alimentos (INTA). Doctor Fernando Monckeberg Barros; Universidad de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera González, C.G. Tabla de Aporte Nutricional; Cámara Chilena del Libro: Santiago, Chile, 2020; p. 123. ISBN 978-956-401-627-6. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes: The Essential Guide to Nutrient Requirements; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 6658:2017; Sensory Analysis. ISO/TC 34/SC 12–Sensory Analysis. The International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Allai, F.M.; Dar, B.N.; Gul, K.; Adnan, M.; Ashraf, S.A.; Hassan, M.I.; Pasupuleti, V.R.; Azad, Z.R.A.A. Development of Protein Rich Pregelatinized Whole Grain Cereal Bar Enriched With Nontraditional Ingredient: Nutritional, Phytochemical, Textural, and Sensory Characterization. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 870819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, Q.; Zheng, J. Structure and Characteristic of β-Glucan in Cereal: A Review. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2015, 39, 3145–3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahidi, F.; Athiyappan, K.D. Polyphenol-Polysaccharide Interactions: Molecular Mechanisms and Potential Applications in Food Systems—A Comprehensive Review. Food Prod. Process. Nutr. 2025, 7, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, H.; Kowalska, J.; Ignaczak, A.; Masiarz, E.; Domian, E.; Galus, S.; Ciurzyńska, A.; Salamon, A.; Zając, A.; Marzec, A. Development of a High-Fibre Multigrain Bar Technology with the Addition of Curly Kale. Molecules 2021, 26, 3939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, T.R.; Corrêa, A.D.; de Carvalho Alves, A.P.; Simão, A.A.; Pinheiro, A.C.M.; de Oliveira Ramos, V. Cereal Bars Enriched with Antioxidant Substances and Rich in Fiber, Prepared with Flours of Acerola Residues. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 5084–5092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kumar, M.; Bharti, A.; Dhumketi, K.; Ansari, F.; Patidar, S.; Tiwari, P.N.; Kumar Kumawat, R.; Thakur, S.; Chauhan, P.; Solan, H.P. Comparative Study of Nutritional and Physical Characteristics of Raw and Puffed Quinoa. Agric. Mech. Asia 2022, 53, 5382–5389. [Google Scholar]

- McMahon, D.J.; Adams, S.L.; Mcmanus, W.R. Hardening of High-Protein Nutrition Bars and Sugar/Polyol-Protein Phase Separation. J. Food Sci. 2009, 74, E312–E321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iuliano, L.; González, G.; Casas, N.; Moncayo, D.; Cote, S. Development of an Organic Quinoa Bar with Amaranth and Chia. Braz. J. Food Technol. 2019, 39, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Román, M.E.; Schoebitz, M.; Fuentealba, J.; García-Viguera, C.; Belchí, M.D.L. Phenolic Compounds in Calafate Berries Encapsulated by Spray Drying: Neuroprotection Potential into the Ingredient. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, L.; Figueroa, C.R.; Valdenegro, M.; Vinet, R. Patagonian Berries: Healthy Potential and the Path to Becoming Functional Foods. Foods 2019, 8, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Viedma, J.; Vergara, C.; Toledo, T.; Zura-Bravo, L.; Flores, M.; Barrera, C.; Lemus-Mondaca, R. Calafate (Berberis buxifolia Lam.) Berry as a Source of Bioactive Compounds with Potential Health-Promoting Effects: A Critical Review. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, A.; Mardones, C.; Vergara, C.; von Baer, D.; Gómez-Alonso, S.; Gómez, M.V.; Hermosín-Gutiérrez, I. Isolation and Structural Elucidation of Anthocyanidin 3,7-β-O-Diglucosides and Caffeoyl-glucaric Acids from Calafate Berries. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 23, 6918–6925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arena, M.E.; Giordani, E.; Bustamante, G.; Radicea, S. Variability in fruit traits and anthocyanin content among and within populations of underutilized Patagonian species Berberis microphylla G. Forst. J. Berry Res. 2021, 11, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Lietz, G.; Seal, C.J. Phenolic, Apparent Antioxidant and Nutritional Composition of Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) Seeds. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 56, 3245–3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratosin, B.C.; Martău, G.A.; Ciont, C.; Ranga, F.; Simon, E.; Szabo, K.; Darjan, S.; Teleky, B.E.; Vodnar, D.C. Nutritional and Physico-Chemical Characteristics of Innovative Bars Enriched with Aronia Melanocarpa By-Product Powder. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.S.; Hwang, C.W.; Yang, W.S.; Kim, C.H. Multiple Antioxidative and Bioactive Molecules of Oats (Avena sativa L.) in Human Health. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredes, C.; Parada, A.; Salinas, J.; Robert, P. Phytochemicals and Traditional Use of Two Southernmost Chilean Berry Fruits: Murta (Ugni molinae Turcz) and Calafate (Berberis buxifolia Lam.). Foods 2020, 9, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobros, N.; Zielińska, A.; Siudem, P.; Zawada, K.D.; Paradowska, K. Profile of Bioactive Components and Antioxidant Activity of Aronia melanocarpa Fruits at Various Stages of Their Growth, Using Chemometric Methods. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nirmala Prasadi, V.P.; Joye, I.J. Dietary Fibre from Whole Grains and Their Benefits on Metabolic Health. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’amaro, D.; Scilingo, A.; Sabbione, A.C. Pseudocereals Dietary Fiber: Amaranth, Quinoa, and Buckwheat Fiber Composition and Potential Prebiotic Effect. Rev. FCA UNcuyo 2024, 56, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paucar-Menacho, L.M.; Vásquez Guzmán, J.C.; Simpalo-Lopez, W.D.; Castillo-Martínez, W.E.; Martínez-Villaluenga, C. Enhancing Nutritional Profile of Pasta: The Impact of Sprouted Pseudocereals and Cushuro on Digestibility and Health Potential. Foods 2023, 12, 4395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alemayehu, G.F.; Forsido, S.F.; Tola, Y.B.; Amare, E. Nutritional and Phytochemical Composition and Associated Health Benefits of Oat (Avena sativa) Grains and Oat-Based Fermented Food Products. Sci. World J. 2023, 2023, 2730175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Rodríguez, J. Use of Amaranth and Its Usefulness in the Treatment of Patients with Diabetes Mellitus. Rev. Cienc. Méd. Pinar del Río 2023, 27, e5931. Available online: https://openurl.ebsco.com/EPDB%3Agcd%3A14%3A17195582/detailv2?sid=ebsco%3Aplink%3Ascholar&id=ebsco%3Agcd%3A173905638&crl=c&link_origin=scholar.google.com (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Ballon Paucara, W.G.; Gutierrez Durán, M.d.P.; Castillo Magariños, C.L.; Mamani Mayta, D.; Grados-Torrez, R.E.; Gonzáles Dávalos, E.L. Effect of a Natural Product Based on Amaranth, Quinoa and Tarwi on Lipid Profile in Patients with Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Rev. Con-Cienc. 2021, 9, 28–45. [Google Scholar]

- Guallo Paca, M.J.; Andrade Albán, M.J.; Mejía Gallegos, F.A.; Barahona Barrera, S.E. Food insecurity and level of anxiety in quinoa producers in the province of Chimborazo. Rev. Cubana Reumatol. 2022, 24, E999. [Google Scholar]

- Mihafu, F.D.; Issa, J.Y.; Kamiyango, M.W. Implication of Sensory Evaluation and Quality Assessment in Food Product Development: A Review. Curr. Res. Nutr. Food Sci. 2020, 8, 690–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutcosky, S.D. Análise Sensorial de Alimentos Silvia Deboni Dutcosky, 5th ed.; PUCPRESS: Curitiba, Brazil, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cardello, A.V.; Schutz, H.G.; Lesher, L.L. Consumer Perceptions of Foods Processed by Innovative and Emerging Technologies: A Conjoint Analytic Study. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2007, 8, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ares, G.; Giménez, A.; Deliza, R. Influence of Three Non-Sensory Factors on Consumer Choice of Functional Yogurts over Regular Ones. Food Qual. Prefer. 2010, 21, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hough, H.; Langohr, K.; Gómez, G.; Curia, A. Survival Analysis Applied to Sensory Shelf Life of Foods. J. Food Sci. 2003, 68, 359–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ingredients (g) | Formulations | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | |

| Oats | 120 | 60 | 120 | 240 |

| Cranberries | 80 | 80 | 80 | 80 |

| Amaranth popcorn | 14 | 21 | 14 | |

| Quinoa popcorn | 14 | 21 | 14 | |

| Honey | 170 | 170 | 170 | 170 |

| Sunflower oil | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Calafate | 24 | 24 | 48 | |

| Formulations | Maximum | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Force (N) | |||

| F1 | 7.31 | ± | 1.24 a |

| F2 | 11.96 | ± | 2.04 b |

| F3 | 20.27 | ± | 2.33 c |

| F4 | 27.63 | ± | 0.18 d |

| Formulations | Total Phenolic Content | Antioxidant Capacity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (mg GAE/100 g Sample) | (µM TE/100 g Sample) | |||||

| F1 | 264.67 | ± | 9.76 a | 1943.19 | ± | 32.46 b |

| F2 | 231.18 | ± | 10.63 b | 1987.37 | ± | 63.04 b |

| F3 | 403.49 | ± | 15.84 c | 2181.68 | ± | 59.01 c |

| F4 | 141.34 | ± | 9.73 d | 1703.12 | ± | 32.78 a |

| Compounds and Percentage | Formulations | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | |||||||||

| Serving Size | 100 g | Serving Size (%) | Serving Size | 100 g | Serving Size (%) | Serving Size | 100 g | Serving Size (%) | Serving Size | 100 g | Serving Size (%) | |

| Calories (Kcal) | 55.68 | 278.4 | 2.80 | 46.8 | 234.1 | 2.30 | 56.12 | 280 | 2.81 | 72.94 | 364.7 | 3.65 |

| % Daily Value * | ||||||||||||

| Total Fat (g) | 0.91 | 4.60 | 0.41 | 0.75 | 3.80 | 0.34 | 0.92 | 4.60 | 0.41 | 1.23 | 6.20 | 0.55 |

| Saturated Fat (g) | 0.31 | 1.50 | 0.14 | 0.36 | 1.80 | 0.16 | 0.33 | 1.60 | 0.15 | 0.18 | 0.90 | 0.08 |

| Monounsaturated Fat (g) | 0.22 | 1.10 | 0.10 | 0.17 | 0.80 | 0.08 | 0.22 | 1.10 | 0.09 | 0.33 | 1.70 | 0.15 |

| Polyunsaturated Fat (g) | 0.46 | 2.30 | 0.21 | 0.40 | 2.0 | 0.18 | 0.46 | 2.30 | 0.21 | 0.58 | 2.90 | 0.26 |

| Sodium (mg) | 0.69 | 3.50 | NA | 0.72 | 3.60 | NA | 0.71 | 3.60 | NA | 0.61 | 3.10 | NA |

| Total Carbohydrate (g) | 11.83 | 59.20 | 2.36 | 10.5 | 52.5 | 2.10 | 12.03 | 60.2 | 2.40 | 14.3 | 71.5 | 2.86 |

| Dietary Fiber (g) | 0.88 | 4.40 | 0.08 | 0.60 | 3.0 | 0.06 | 0.97 | 4.90 | 0.09 | 1.33 | 6.60 | 0.13 |

| Total Sugars (g) | 6.79 | 34.0 | 1.36 | 6.78 | 33.9 | 1.36 | 6.87 | 34.4 | 1.37 | 6.73 | 33.7 | 1.35 |

| Protein (g) | 1.07 | 5.30 | 0.21 | 0.63 | 3.10 | 0.12 | 1.10 | 5.50 | 0.22 | 1.92 | 9.60 | 0.38 |

| % RDI ** | ||||||||||||

| Calcium (mg) | 4.24 | 21.20 | 0.50 | 2.89 | 14.5 | 0.40 | 4.41 | 22.0 | 0.60 | 6.77 | 33.8 | 0.80 |

| Magnesium (mg) | 11.60 | 58.0 | 3.70 | 7.32 | 36.6 | 2.30 | 11.71 | 58.60 | 3.70 | 20.05 | 100.2 | 6.40 |

| Phosphorus (mg) | 32.96 | 164.8 | 4.10 | 19.92 | 99.6 | 2.50 | 33.18 | 165.9 | 4.10 | 58.83 | 294.2 | 7.40 |

| Potassium (mg) | 12.19 | 60.90 | 0.40 | 13.89 | 69.5 | 0.50 | 13.43 | 67.20 | 0.40 | 7.53 | 37.7 | 0.30 |

| Zinc (mg) | 0.40 | 2.0 | 3.30 | 0.30 | 1.50 | 2.50 | 0.40 | 2.0 | 3.30 | 0.46 | 2.30 | 3.80 |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 1.38 | 6.90 | 0.20 | 1.38 | 6.90 | 0.20 | 2.20 | 11.0 | 1.80 | 0.56 | 2.80 | 0.13 |

| Thiamine B1 (mg) | 0.04 | 0.20 | 3.25 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 1.82 | 0.04 | 0.20 | 3.25 | 0.07 | 0.40 | 6.10 |

| Riboflavin B2 (mg) | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.83 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.83 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.83 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 1.60 |

| Niacin B3 (mg) | 0.08 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.05 | 0.30 | 0.40 | 0.08 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.12 | 0.60 | 0.80 |

| Pantothenic acid B5 (mg) | 0.10 | 0.50 | 2.0 | 0.07 | 0.30 | 1.40 | 0.10 | 0.50 | 0.20 | 0.17 | 0.80 | 3.30 |

| Pyridoxine B6 (mg) | 0.02 | 0.10 | 1.20 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 1.10 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 1.20 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 1.20 |

| Folate B9 (µg) | 3.82 | 19.10 | 1.0 | 2.51 | 12.60 | 0.60 | 3.82 | 19.10 | 1.0 | 6.42 | 32.10 | 1.60 |

| Formulations | Acceptance | Acceptability Index (%) | Preference | Intention to Purchase | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 6.06 | ± | 1.24 a | 67.30 a | 6.60 | ± | 1.06 a | 3.57 | ± | 1.01 a |

| F2 | 7.06 | ± | 1.73 b | 78.41 b | 7.57 | ± | 1.38 b | 4.03 | ± | 1.15 a |

| F3 | 6.54 | ± | 1.77 ab | 72.70 c | 7.06 | ± | 1.26 ab | 3.83 | ± | 1.15 a |

| F4 | 6.57 | ± | 1.84 ab | 73.01 c | 6.80 | ± | 1.64 a | 3.63 | ± | 1.31 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

López, J.; Cea, R.; Tiznado, N.; Fernández, E.; González, M.L.; Pizarro-Oteíza, S.; Pérez-Cervera, C. Development of Cereal Bars Enriched with Andean Grains and Patagonian Calafate (Berberis microphylla): Nutritional Composition, Phenolic Content, Antioxidant, Textural, and Sensory Evaluation. Foods 2025, 14, 4127. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234127

López J, Cea R, Tiznado N, Fernández E, González ML, Pizarro-Oteíza S, Pérez-Cervera C. Development of Cereal Bars Enriched with Andean Grains and Patagonian Calafate (Berberis microphylla): Nutritional Composition, Phenolic Content, Antioxidant, Textural, and Sensory Evaluation. Foods. 2025; 14(23):4127. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234127

Chicago/Turabian StyleLópez, Jéssica, Romina Cea, Nicole Tiznado, Evelyn Fernández, María Lorena González, Sebastián Pizarro-Oteíza, and Carmen Pérez-Cervera. 2025. "Development of Cereal Bars Enriched with Andean Grains and Patagonian Calafate (Berberis microphylla): Nutritional Composition, Phenolic Content, Antioxidant, Textural, and Sensory Evaluation" Foods 14, no. 23: 4127. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234127

APA StyleLópez, J., Cea, R., Tiznado, N., Fernández, E., González, M. L., Pizarro-Oteíza, S., & Pérez-Cervera, C. (2025). Development of Cereal Bars Enriched with Andean Grains and Patagonian Calafate (Berberis microphylla): Nutritional Composition, Phenolic Content, Antioxidant, Textural, and Sensory Evaluation. Foods, 14(23), 4127. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234127