Cold Shock-Induced Nanocomposite Polymer Packaging Maintains Postharvest Quality of Vegetable Soybeans

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Treatments

2.2. Measurement of Browning Index, Weight Loss Rate, Vitamin C Content, Firmness, and Color Parameters in Vegetable Soybeans During Storage

2.3. Measurement of Chlorophyll, MDA, Total Phenolic Content, and Total Flavonoid Content in Vegetable Soybeans During Storage

2.4. Measurement of Hydrogen Peroxide (H2O2), Superoxide Anion (O2·−), Hydroxyl Radical (OH−) Scavenging Activities, and DPPH Radical Scavenging Capacity in Vegetable Soybeans During Storage

2.5. Measurement of Reactive Oxygen Species-Related Enzyme Activities in Vegetable Soybeans During Storage

2.6. Data Processing

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Cold Shock Treatment on the Postharvest Physiological Quality of Vegetable Soybeans

3.2. Effects of Cold Shock Treatment on Reactive Oxygen Species Metabolism and Antioxidant System in Vegetable Soybeans

3.3. Effects of Nanocomposite Polymer Packaging on Physiological and Nutritional Quality of Vegetable Soybeans During Postharvest Storage

3.4. Effects of Nanocomposite Polymer Packaging on Reactive Oxygen Species and Antioxidant Quality in Vegetable Soybeans During Postharvest Storage

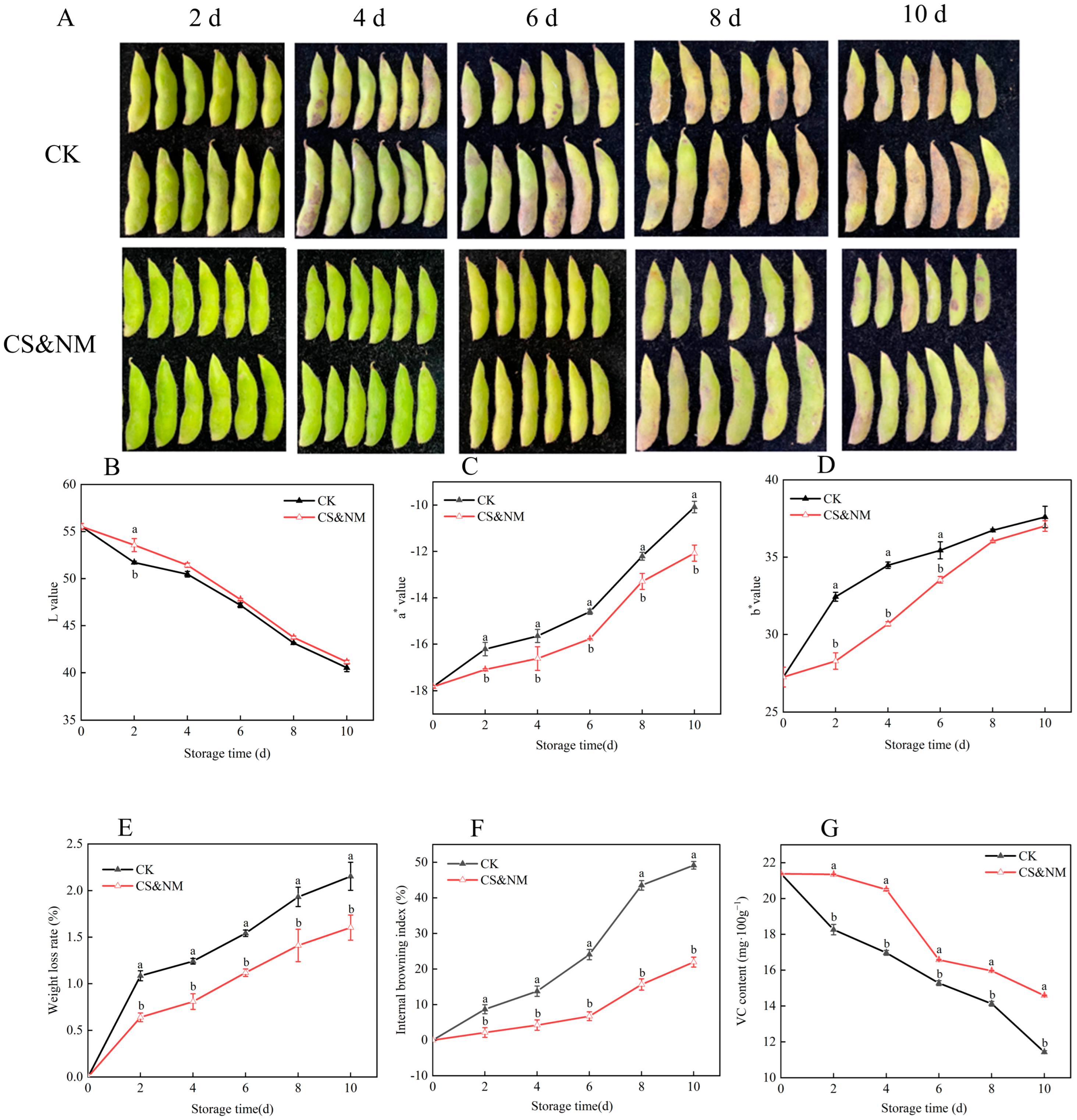

3.5. Effects of Cold Shock Combined with Nanocomposite Polymer Packaging on Physiological and Nutritional Quality of Vegetable Soybeans During Postharvest Storage

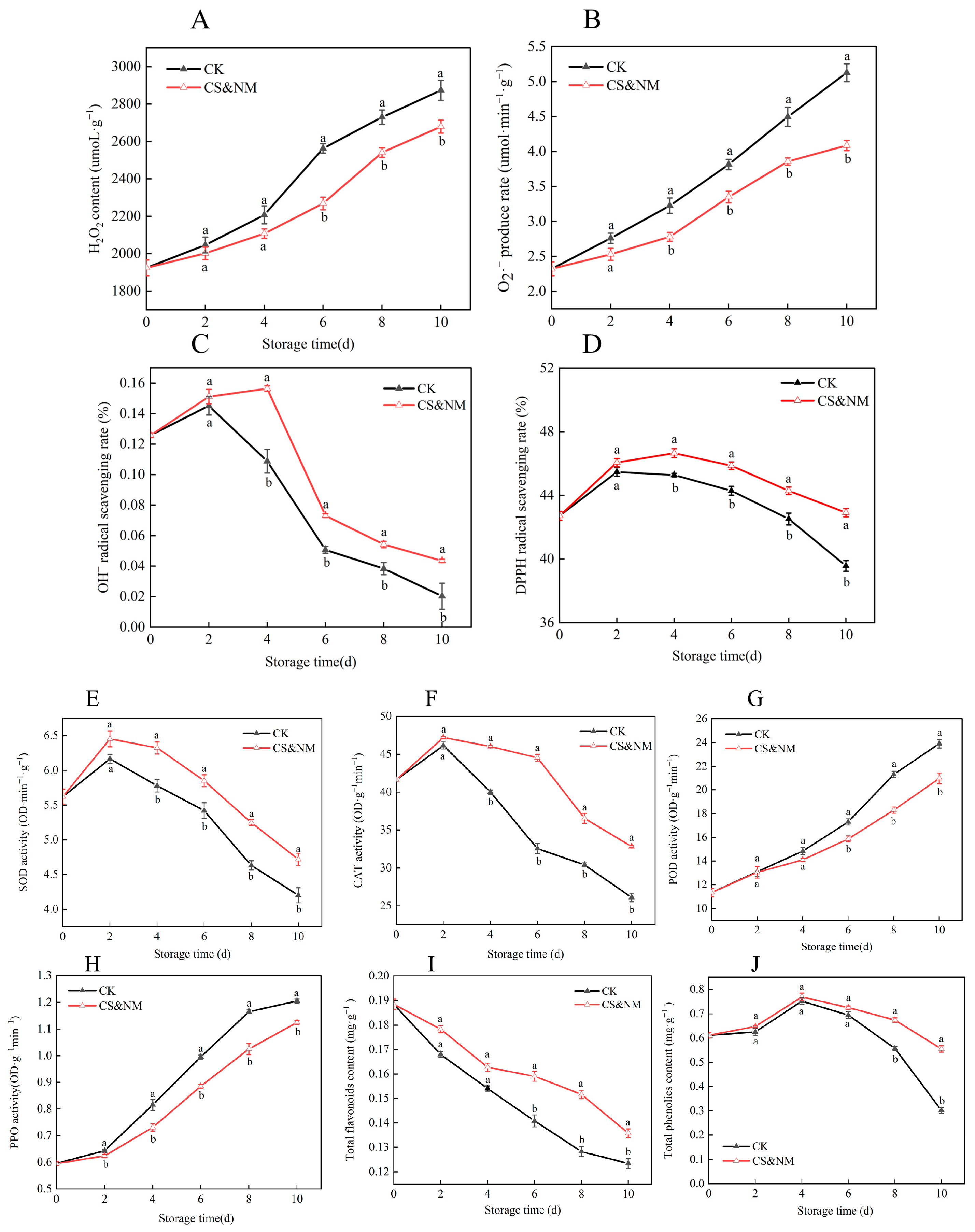

3.6. Effects of Cold Shock Combined with Nanocomposite Polymer Packaging on Postharvest Reactive Oxygen Species Metabolism and Antioxidant Quality in Vegetable Soybeans

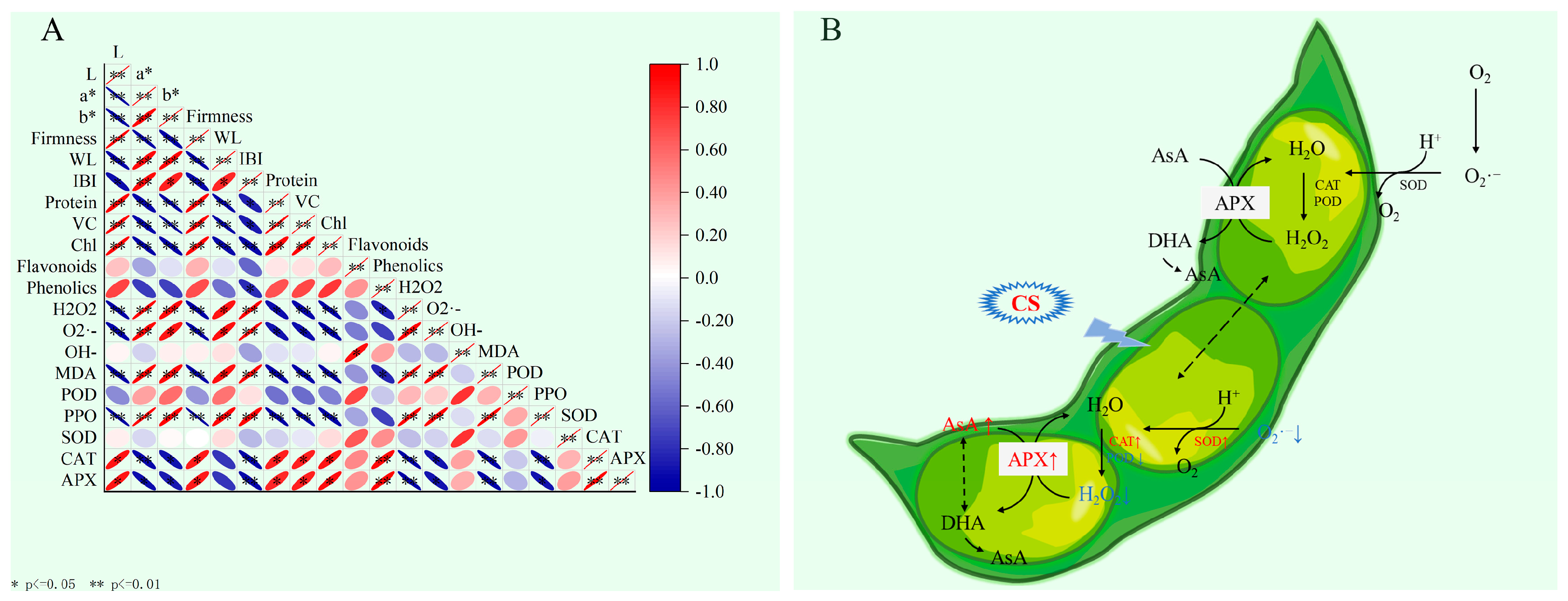

3.7. Correlation Analysis and Putative Regulatory Mechanisms

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Gao, X.; Li, S.; Qin, S.; He, Y.; Yang, Y.; Tian, Y. Hollow discrimination of edamame with pod based on hyperspectral imaging. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2025, 137, 106904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Yang, Z.; Jin, Q.; Wang, H.; Duncan, S.; Yin, Y.; Huang, H. Production and properties of soluble dietary fiber from edamame shell using combined physical and chemical treatments. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 5, 2962–2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, D.K.; Fu, X.J.; Yuan, F.J.; Chen, P.Y.; Zhu, S.L.; Li, B.Q.; Yang, Q.H.; Yu, X.M.; Zhu, D.H. Genetic diversity and population structure of vegetable soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.) in China as revealed by SSR markers. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2014, 61, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyenim-Boateng, K.G.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, S.; Khattak, A.N.; Shaibu, A.; Abdelghany, A.M.; Sun, J. The nutritional composition of the vegetable soybean (maodou) and its potential in combatting malnutrition. Front. Nutr. 2023, 9, 1034115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sreechithra, T.V.; Sakhare, S.D. Impact of processing techniques on the nutritional quality, antinutrients, and in vitro protein digestibility of milled soybean fractions. Food Chem. 2025, 485, 144565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arikit, S.; Yoshihashi, T.; Wanchana, S.; Tanya, P.; Juwattanasomran, R.; Srinives, P.; Vanavichit, A. A PCR-based marker for a locus conferring aroma in vegetable soybean (Glycine max L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 2011, 122, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.F.; Wang, C.L.; Hu, Y.F.; Wen, Y.C.; Sun, Z.B. Biocontrol of three severe diseases in soybean. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nian, Y.; Wang, N.; Li, R.; Shao, Y.; Li, W. Cold shock treatment alleviates chilling injury in papaya fruit during storage by improving antioxidant capacity and related gene expression. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 294, 110784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Liu, C.; Huang, Q.; Wang, W.; Dong, H.; Liao, W.; He, Q. “Chilling-induced hardening” or “chilling-induced softening”? A scientific insight on cold shock effects on strawberry phenotypic quality and pectin metabolism. Food Chem. 2025, 487, 144831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, S.; Xu, D.; Zhou, F.; Gao, H.; Hu, W.; Gao, X.; Jiang, A. Cold shock treatment maintains quality and induces relative expression of cold shock domain protein (CSDPs) in postharvest sweet cherry. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 262, 109058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Liu, W.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, X.; Wang, X.; Mi, S. Improvement of storage quality of broccoli using a cold-shock precooling way and the related molecular mechanisms. Foods 2024, 13, 3401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mi, S.; Li, T.; Sang, Y.; Wang, X.; Duan, Y. Effect of cold shock precooling on the physicochemical, physiological properties and volatile profiles of chili peppers during postharvest storage. LWT 2023, 187, 115300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Montes, E.; Castro-Muñoz, R. Edible films and coatings as food-quality preservers: An overview. Foods 2021, 10, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, X.; Li, S.; Li, S.; Ke, K.; Pang, J.; Wu, C.; Yan, Z. High antibacterial activity of chitosan films with covalent organic frameworks immobilized silver nanoparticles. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 202, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Sathiyaseelan, A.; Zhang, X.; Jin, Y.; Wang, M.H. Yam mucilage nanocomposite film incorporated silver nanoparticles extend the shelf life and preserve the postharvest quality of Agaricus bisporus. Prog. Org. Coat. 2025, 206, 109332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Kumari, A.; Sharma, R. Safe and sustainable food packaging: Argemone albiflora mediated green synthesized silver-carrageenan nanocomposite films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 264, 130626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, R.; Kramer, E.; Oomen, A.G.; Herrera Rivera, Z.E.; Oegema, G.; Tromp, P.C.; Bouwmeester, H. Presence of nano-sized silica during in vitro digestion of foods containing silica as a food additive. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 2441–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koirala, P.; Nirmal, N.P.; Woraprayote, W.; Visessanguan, W.; Bhandari, Y.; Karim, N.U.; Saricaoğlu, F.T. Nano-engineered edible films and coatings for sea food products. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2023, 38, 101135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Fang, D.; Huang, C.; Zhou, A.; Lu, T.; Wang, J.; Li, W. Active Electrospun nanofiber packaging maintains the preservation quality and antioxidant activity of blackberry. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2023, 199, 112300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Hu, Q.; Mariga, A.M.; Cao, C.; Yang, W. Effect of nano packaging on preservation quality of Nanjing 9108 rice variety at high temperature and humidity. Food Chem. 2018, 239, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, D.; Yang, W.; Kimatu, B.M.; Mariga, A.M.; Zhao, L.; An, X.; Hu, Q. Effect of nanocomposite-based packaging on storage stability of mushrooms (Flammulina velutipes). Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2016, 33, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, N.; Zhang, D.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Ma, H. Controlled atmosphere storage alleviates the browning of walnut (Juglans regia L.) fruit through enhancing GABA-mediated energy metabolism. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2024, 210, 112765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Kou, X.; Qiao, L.; Li, J.; Luo, D.; Wang, X.; Cao, S. Maintaining quality of postharvest green pepper fruit using melatonin by regulating membrane lipid metabolism and enhancing antioxidant capacity. Food Chem. 2024, 460, 140671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Z.; Li, D.; Yan, L.; Feng, Y.; Zhao, Z. Resistance index and browning mechanism of apple peel under high temperature stress. Hortic. Plant J. 2024, 10, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.; Li, J.; Tao, J.; Song, Z.; Ji, S.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, Q. Exogenous spermidine treatment delays the softening of postharvest blueberry fruit by inhibiting the accumulation of abscisic acid. Future Postharvest Food 2024, 1, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Yang, Y.; Fang, B.; Uddin, S.; Liu, X. The CrMYB33 transcription factor positively coordinate the regulation of both carotenoid accumulation and chlorophyll degradation in the peel of citrus fruit. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 209, 108540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, S.; Shi, Y.; Zhu, B.; Yang, Y.; Nian, S.; Wang, K.; Kou, L. Methyl jasmonate alleviates the husk browning and regulates expression of genes related to phenolic metabolism of pomegranate fruit. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 338, 113783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Cassan-Wang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Bao, Y.; Hou, Y.; Liu, Y.; Jin, P. Calcium-dependent protein kinase PpCDPK29-mediated Ca2+-ROS signal and PpHSFA2a phosphorylation regulate postharvest chilling tolerance of peach fruit. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2025, 23, 1938–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Q.; Zhao, Q. Exogenous melatonin delays postharvest fruit senescence and maintains the quality of sweet cherries. Food Chem. 2019, 301, 125311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Luo, D.; Kou, X.; Ye, S.; Li, J.; Ba, L.; Cao, S. Carvacrol enhances antioxidant activity and slows down cell wall metabolism by maintaining the energy level of ‘Guifei’mango. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2025, 105, 2134–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshalani, K.A.; Hassanpour, H.; Manda-Hakki, K. Changes in Postharvest quality and antioxidant characteristics of “Dargazi” pear fruit influenced by L-cysteine. Appl. Food Res. 2025, 52, 101293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Yang, H.; Wu, W.; Lyu, L.; Li, W. Variation in antioxidant enzyme activity and key gene expression during fruit development of blackberry and blackberry–raspberry hybrids. Food Biosci. 2023, 54, 102892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zheng, Y.; Li, M.; Zeng, L.; Sang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Fan, Z. Quantitative analyses of major enzyme activities in postharvest fruit. Future Postharvest Food 2024, 1, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medda, S.; Dessena, L.; Mulas, M. Monitoring of the PAL enzymatic activity and polyphenolic compounds in leaves and fruits of two myrtle cultivars during maturation. Agriculture 2020, 10, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Wu, G.; Wu, F.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, K.; Li, H. Genome-wide association analysis of yield-related traits and candidate genes in vegetable soybean. Plants 2024, 13, 1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Liu, N.; Mao, W.; Hu, Q.; Wang, G.; Gong, Y. Identification of chilling-responsive microRNAs and their targets in vegetable soybean (Glycine max L.). Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Wei, Y.; Jiang, S.; Xu, F.; Wang, H.; Zhan, P.; Shao, X. ROS stress and cell membrane disruption are the main antifungal mechanisms of 2-phenylethanol against Botrytis cinerea. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 14468–14479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Yang, Q.; Zhao, Q.; Li, X. Cold shock treatment with oxalic acid could alleviate chilling injury in green bell pepper by enhancing antioxidant enzyme activity and regulating proline metabolism. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 295, 110783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, D.; Yang, W.; Kimatu, B.M.; An, X.; Hu, Q.; Zhao, L. Effect of nanocomposite packaging on postharvest quality and reactive oxygen species metabolism of mushrooms (Flammulina velutipes). Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2016, 119, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Mi, S.; Chitrakar, B.; Li, J.; Wang, X. Effect of cold shock pretreatment combined with perforation-mediated passive modified atmosphere packaging on storage quality of cucumbers. Foods 2022, 11, 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, L.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Bi, Y. Postharvest combined chitosan and melatonin treatment maintain antioxidant capacity and cell membrane integrity of fresh-cut broccoli by inducing reactive oxygen species scavenging system. LWT 2025, 220, 117572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Lin, H.; Lin, H.T.; Lin, M.S.; Wang, H.; Wei, W.; Fan, Z.Q. The metabolism of membrane lipid participates in the occurrence of chilling injury in cold-stored banana fruit. Food Res. Int. 2023, 173, 113415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, T.; Zhuang, X.; Chang, J.; Gao, Y.; Bai, X. Effect of surface-immobilized states of antimicrobial peptides on their ability to disrupt bacterial cell membrane structure. J. Funct. Biomater. 2024, 15, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurcholis, W.; Alfadzrin, R.; Izzati, N.; Arianti, R.; Vinnai, B.Á.; Sabri, F.; Artika, I.M. Effects of methods and durations of extraction on total flavonoid and phenolic contents and antioxidant activity of java cardamom (Amomum compactum Soland Ex Maton) fruit. Plants 2022, 11, 2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balubhai, T.P.; Asrey, R.; Menaka, M.; Vinod, B.R.; Vargheese, E.; Khandelwal, A.; Varsha, K. Enhancing the antioxidant system and preserving nutritional quality of Indian Ber (Ziziphus mauritiana L.) fruit following melatonin application. Food Res. Int. 2025, 208, 116251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlahla, J.M.; Mafa, M.S.; van Der Merwe, R.; Moloi, M.J. Tolerance to combined drought and heat stress in edamame is associated with enhanced antioxidative responses and cell wall modifications. Physiol. Plant. 2025, 177, e70187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, S.; Shen, P.; Ren, Y.; Li, S.; Jin, P.; Zheng, Y.; Wu, Z. Modified SiO2@cinnamaldehyde/nanocellulose coating film for loquat preservation. Int. J. Biol Macromol. 2024, 278, 134862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Q.; Lin, X.; Yang, Y.; Duan, B. Multifunctional edible chitin nanofibers/ferulic acid composite coating for fruit preservation. J. Polym. Sci. 2024, 62, 338–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Long, Q.; Gao, F.; Han, C.; Jin, P.; Zheng, Y. Effect of cutting styles on quality and antioxidant activity in fresh-cut pitaya fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2017, 124, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin, Y.; Wu, X.; Shi, J.; Zhao, Y.; Yue, X.; Xu, X.; Wang, Q. Rutin treatment delays postharvest chilling injury in green pepper fruit by modulating antioxidant defense capacity. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2025, 230, 113753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Wang, X.; Chen, J.; Luo, D.; Cao, S.; Ba, L. Putrescine maintains postharvest pitaya quality by regulating polyamine and reactive oxygen homeostasis and energy metabolism. LWT 2025, 220, 117573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, T.; Su, N.; Liu, W.; Gao, M.; Li, R.; Bi, Y. L-Phenylalanine preharvest spraying effectively enhances the reactive oxygen metabolism and antioxidant capacity in postharvest broccoli. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 227, 110185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, Q.; Xiao, F.; Yang, J.; Zhou, S.; Tang, M.; Zhai, X. Black Tea Aqueous Extract Extends Yeast Longevity via Antioxidant Gene Activation: Transcriptomic Analysis of Anti-Aging Mechanisms. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 13, e70661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Bao, G.; Chen, S.; Yuan, Y.; Li, N.; Hu, J.; Jiang, H. The regulatory network of antioxidant enzyme synergy in ROS homeostasis and Photosynthesis: Multilevel response mechanisms of rye seedlings under nicosulfuron-atrazine-freeze-thaw combined stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 229, 110401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, R.; Sati, H.; Oberoi, H.S.; Pareek, S. The mechanisms of melatonin in low-temperature stress tolerance in postharvest fruits and vegetables. Future Postharvest Food 2024, 1, 180–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, X.; Zhao, L.; Liang, X.; Zheng, Y.; Jin, P. Cold Shock-Induced Nanocomposite Polymer Packaging Maintains Postharvest Quality of Vegetable Soybeans. Foods 2025, 14, 4129. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234129

Wang X, Zhao L, Liang X, Zheng Y, Jin P. Cold Shock-Induced Nanocomposite Polymer Packaging Maintains Postharvest Quality of Vegetable Soybeans. Foods. 2025; 14(23):4129. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234129

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xiaogang, Liangyi Zhao, Xiaohuan Liang, Yonghua Zheng, and Peng Jin. 2025. "Cold Shock-Induced Nanocomposite Polymer Packaging Maintains Postharvest Quality of Vegetable Soybeans" Foods 14, no. 23: 4129. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234129

APA StyleWang, X., Zhao, L., Liang, X., Zheng, Y., & Jin, P. (2025). Cold Shock-Induced Nanocomposite Polymer Packaging Maintains Postharvest Quality of Vegetable Soybeans. Foods, 14(23), 4129. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234129