Plant Growth Regulator Residues in Edible Mushrooms: Are They Hazardous?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Reagents

2.2. Samples Pre-Treatment

2.3. LC-MS/MS Analysis

2.4. Analytical Method Validation

2.5. Exposure Risk Assessment

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Method Validation

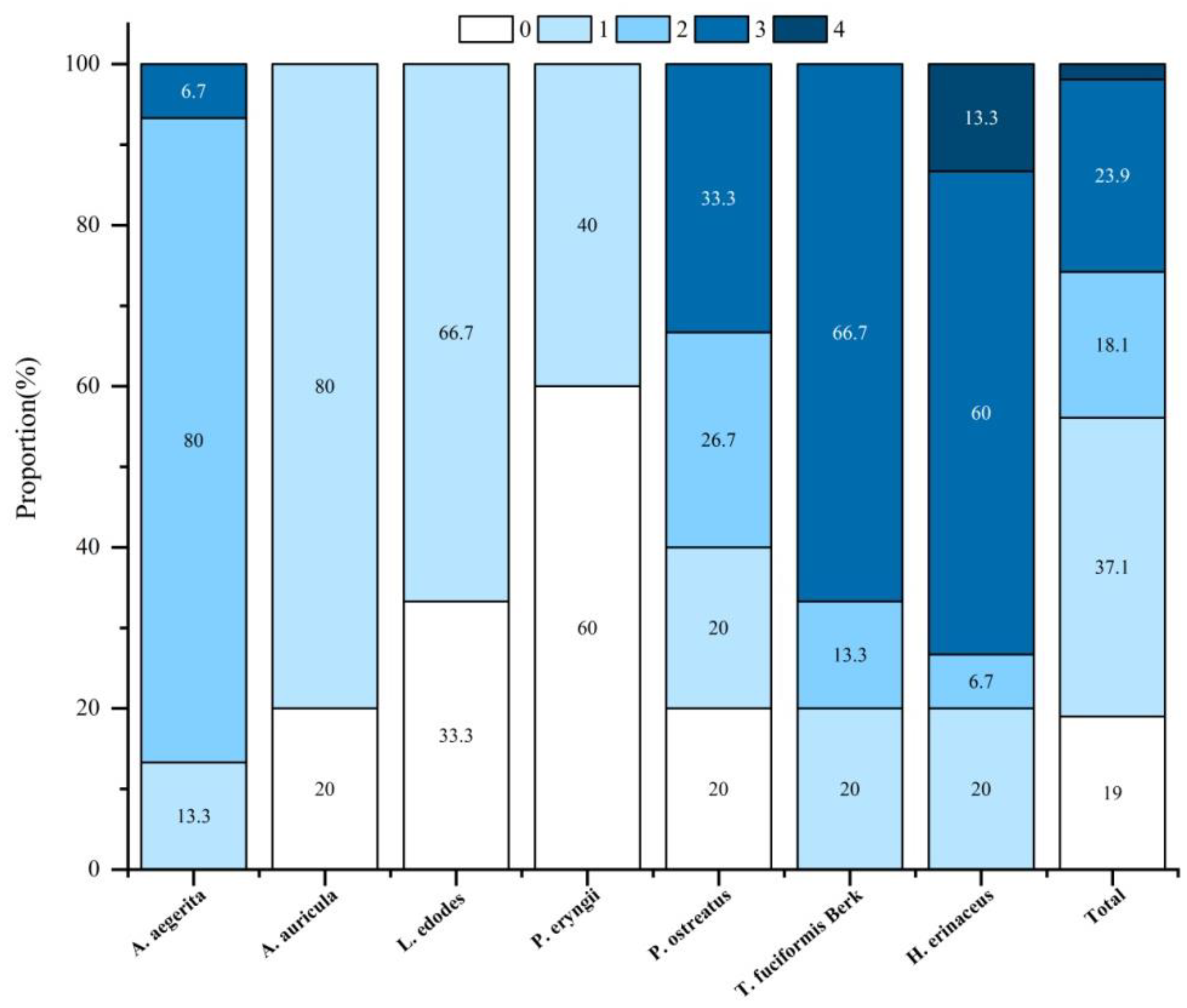

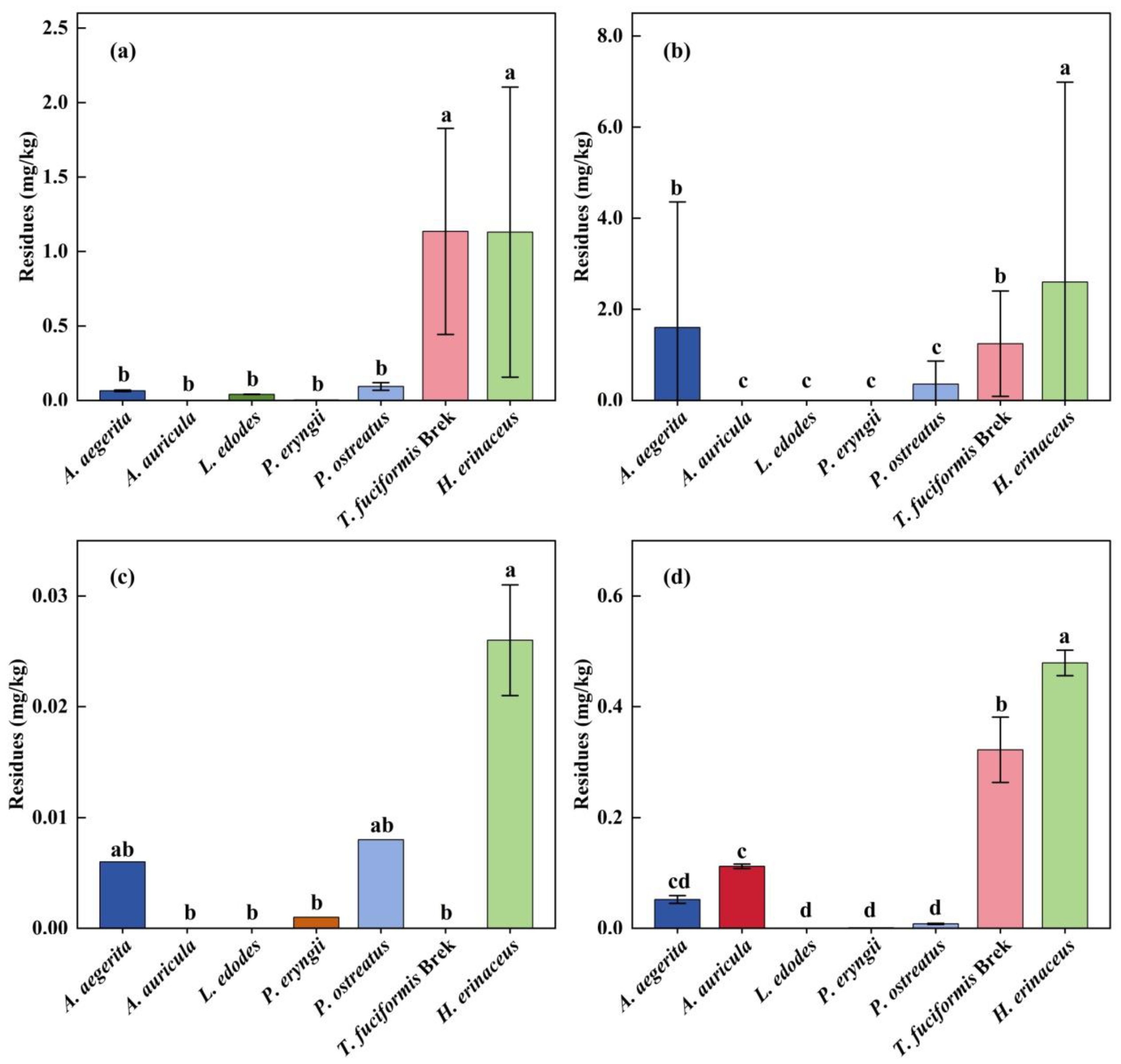

3.2. PGR Residues in Edible Mushrooms

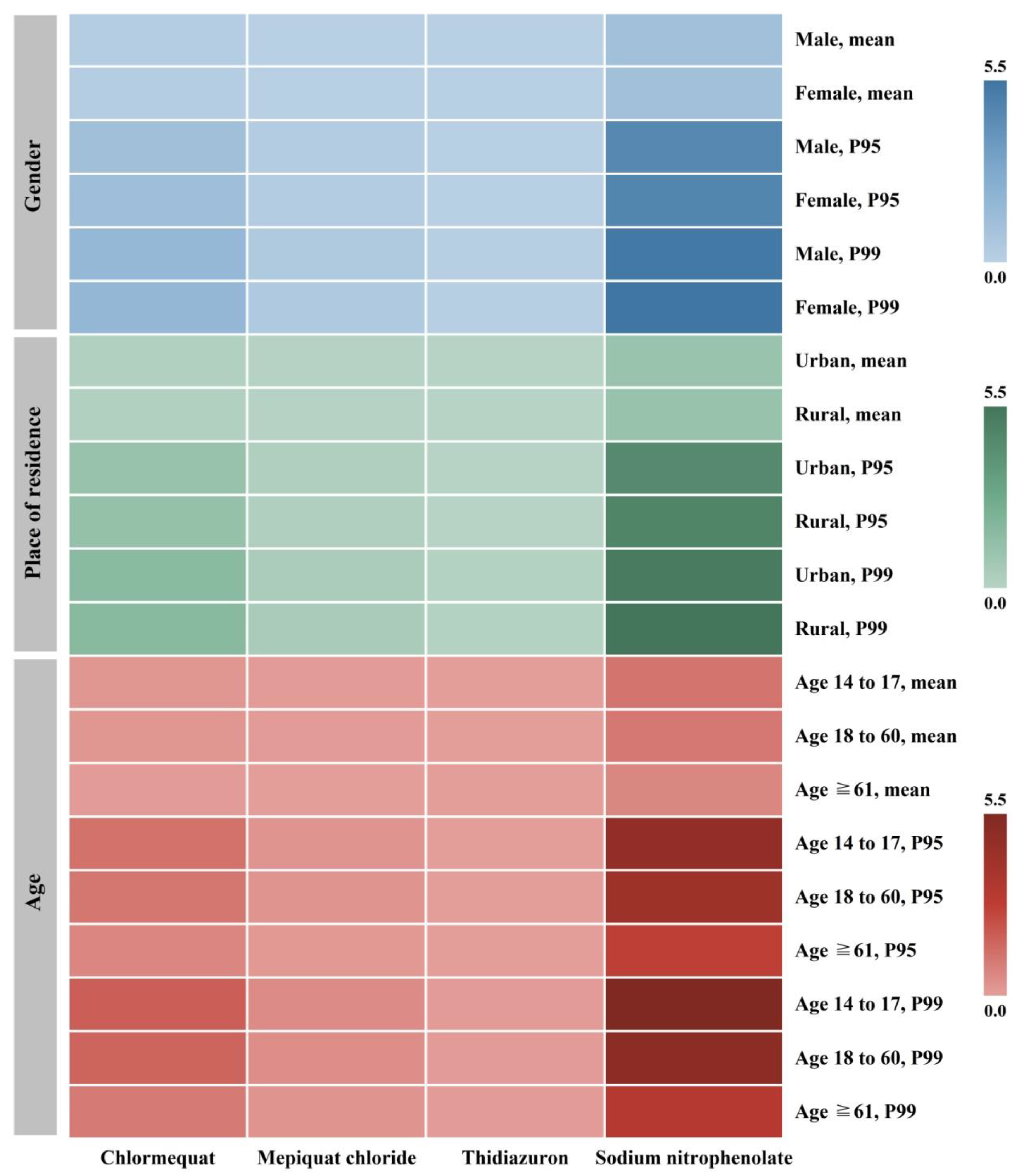

3.3. Deterministic Intake Calculations

3.3.1. Long-Term Intake and Chronic Exposure Risk

3.3.2. Short-Term Intake and Acute Exposure Risk

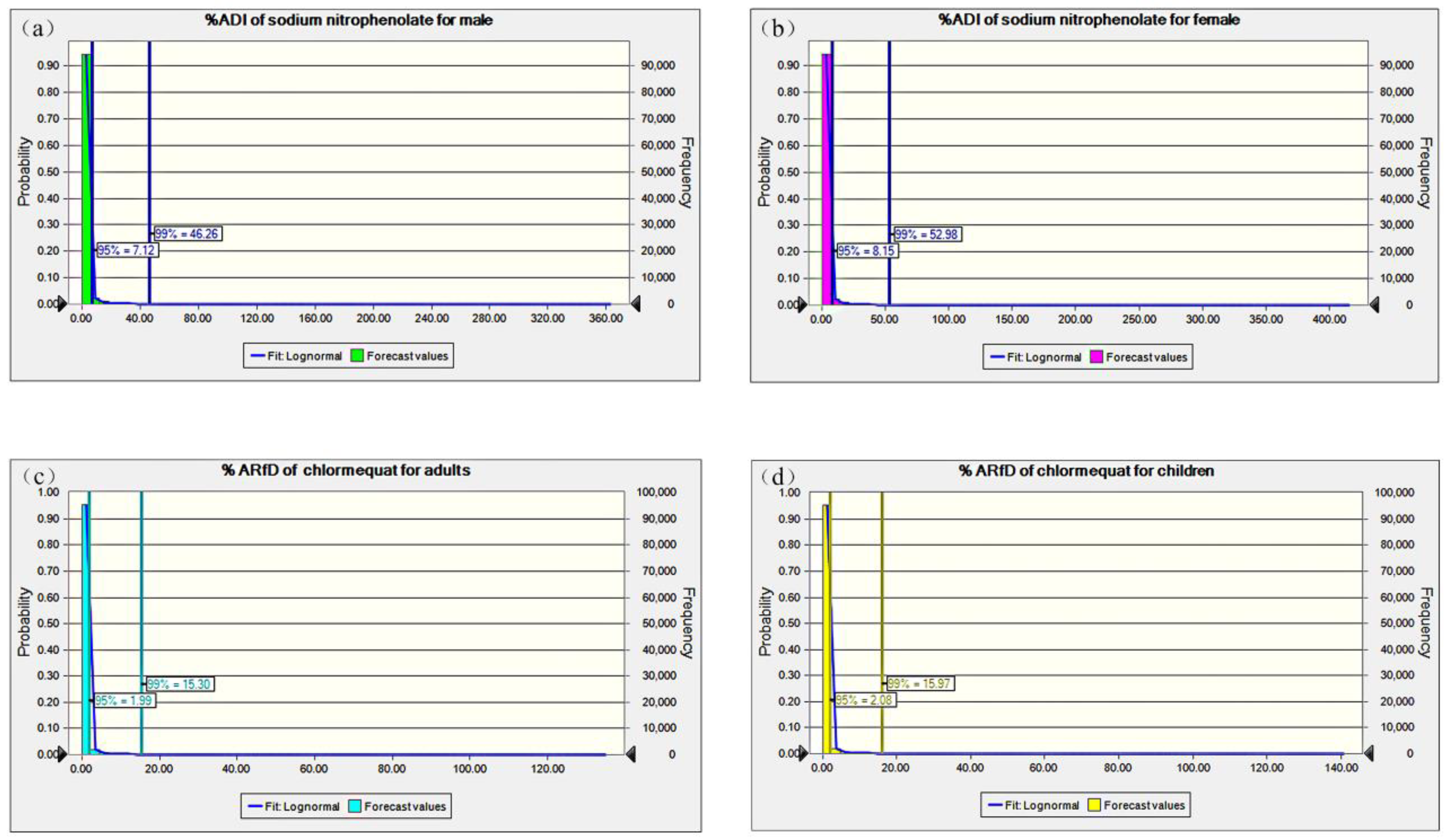

3.4. Probabilistic Intake Calculation

3.5. Strengths, Limitations, and Future Perspectives

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yuan, S.; Huang, C.; Gao, W. Unlocking the potential of edible mushroom proteins: A sustainable future in food and health. Food Chem. 2025, 481, 144026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowlati, M.; Sobhi, H.R.; Esrafili, A.; FarzadKia, M.; Yeganeh, M. Heavy metals content in edible mushrooms: A systematic review, meta-analysis and health risk assessment. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 109, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Liu, D.; Gao, L.; Ouyang, Y.; Wen, Y.; Ai, C.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, C. Health benefits of Grifola frondosa polysaccharide on intestinal microbiota in type 2 diabetic mice. Food Sci. Hum. Well. 2022, 11, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Fang, J.; Guo, Q.; Wang, M.; Li, Y.; Meng, Y.; Huang, L. Advances in antiviral polysaccharides derived from edible and medicinal plants and mushrooms. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 229, 115548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Yao, Z.; Xiao, Z.; Zhu, G.; Zhu, J.; Chen, J. Sensory evaluation of the synergism among ester odorants in light aroma-type liquor by odor threshold, aroma intensity and flash GC electronic nose. Food Res. Int. 2018, 113, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Sheikha, A.F.; Hu, D.M. How to trace the geographic origin of mushrooms? Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 78, 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosoh, D.A. Plant growth regulator studies and emerging biotechnological approaches in Artemisia annua L.: A comprehensive overview. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2025, 181, 181–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Gong, D.; Zhao, K.; Chen, D.; Dong, Y.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Q.; Hao, G. Research and development trends in plant growth regulators. Adv. Agrochem. 2024, 3, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rademacher, W. Plant growth regulators: Backgrounds and uses in plant production. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2015, 34, 845–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Ma, L.; Su, D.; Xiagedeer, B. The disrupting effect of chlormequat chloride on growth hormone is associated with pregnancy. Toxicol. Lett. 2024, 395, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Jin, F.; Yu, Z.; Qi, Y.; Shi, X.; Wang, M.; Shao, H.; Jin, M.; Wang, J.; Yang, M. Rapid determination of chlormequat in meat by dispersive solid-phase extraction and hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC)-electrospray tandem mass spectrometry. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 6816–6822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiagedeer, B.; Hou, X.; Zhang, Q.; Hu, H.; Kang, C.; Xiao, Q.; Hao, W. Maternal chlormequat chloride exposure disrupts embryonic growth and produces postnatal adverse effects. Toxicology 2020, 442, 152534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehnert, G.K.; Karasov, W.H.; Wolman, M.A. 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid containing herbicide impairs essential visually guided behaviors of larval fish. Aquat. Toxicol. 2019, 209, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Li, H.; Wang, F.; Wang, H.; Chai, R.; Li, J.; Jia, L.; Wang, K.; Zhang, P.; Zhu, L.; et al. Effects of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid on the expression of NLRP3 inflammasome and autophagy-related proteins as well as the protective effect of Lyciumbarbarum polysaccharide in neonatal rats. Environ. Toxicol. 2021, 36, 2454–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ma, Y.; Jia, L.; Luo, X.; Wang, H.; Yang, H.; Zhou, J. Plant growth regulator residues in fruits and vegetables marketed in Yinchuan and exposure risk assessment. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2023, 124, 105661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MOA (Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China). The Reports of Investigation on the Quality and Safety of Pesticide Residues in Edible Mushrooms. 2020; (In Chinese). Available online: https://jgs.moa.gov.cn/gzjb/202010/t20201020_6354686.htm (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Fang, S.; Gao, K.; Hu, W.; Wang, S.; Chen, B.; Zhou, Z. Foliar and seed application of plant growth regulators affects cotton yield by altering leaf physiology and floral bud carbohydrate accumulation. Field Crops Res. 2019, 231, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, R.; Wang, W.; Zhao, X.; Du, Y.; Yin, H. Effects of chitosan oligosaccharides on the yield components and production quality of different wheat cultivars (Triticum aestivum L.) in Northwest China. Field Crops Res. 2015, 172, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Liang, X.; Zhang, L.; Lin, S.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, L.; Shen, S.; Zhou, S. Spraying exogenous 6-benzyladenine and brassinolide at tasseling increases maize yield by enhancing source and sink capacity. Field Crops Res. 2017, 211, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 2763-2021; National Food Safety Standard—Maximum Residue Limits for Pesticides in Food. MOA (Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China): Beijing, China, 2021. (In Chinese)

- GB 2763.1-2022; National Food Safety Standard—Maximum Residue Limits for 112 Pesticides in Food. MOA (Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China): Beijing, China, 2022. (In Chinese)

- Liu, T.; Zhang, C.; Peng, J.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, X.; Xiao, H.; Sun, K.; Pan, L.; Liu, X.; Tu, K. Residual behaviors of six pesticides in shiitake from cultivation to postharvest drying process and risk assessment. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 8977–8985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Q.; Su, D.; Zheng, Y.; Huang, M.; Chen, M.; Xu, H.; Zeng, S. Risk assessment of multiple pesticide residues in Agrocybe aegerita: Based on a 3-year monitoring survey. Food Chem. X 2024, 22, 101323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Chang, W.; Bao, C.; Zhuang, Y. Metal Contents, Bioaccumulation, and Health Risk Assessment in Wild Edible Boletaceae Mushrooms. J. Food Sci. 2017, 82, 1500–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Huang, Q.; Cai, H.; Guo, X.; Wang, T.; Gui, M. Study of heavy metal concentrations in wild edible mushrooms in Yunnan Province, China. Food Chem. 2015, 188, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Kontor-Manu, E.; Zhu, H.; Cheng, G.; Feng, Y. Evaluation of the Handling Practices and Risk Perceptions of Dried Wood Ear Mushrooms in Asian Restaurants in the United States. J. Food Prot. 2024, 87, 100198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Dai, M.; Bai, L.; Wang, J.; Peng, Z.; Qu, Y.; Chen, S.; Yang, X.; Bai, Y.; Zhou, C.; et al. Assessing safety risks associated with Burkholderia gladiolus in soaked Auricularia auricula-judae: One instant predictive model study. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2025, 436, 111212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GB/T 8855-2008; Fresh Fruits and Vegetables-Sampling. The Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2008. (In Chinese)

- Su, D.; Lin, X.; Zheng, Y.; Zeng, L.; Huang, M.; Chen, G.; Yao, Q. Determination of 11 Growth Regulators in Cottonseed Hulls by HPLC-MS/MS. Chin. J. Pestic. Sci. 2025, 27, 947–957. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- SANTE. Guidance Document on Analytical Quality Control and Method Validation Procedures for Pesticide Residues Analysis in Food and Feed; Document No. SANTE/11312/2021; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2025; pp. 1–43. Available online: https://www.eurl-pesticides.eu/docs/public/tmplt_article.asp?CntID=727 (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- ISO/IEC 17025; General Requirements for the Competence of Testing and Calibration Laboratories. International Organization for Standardization (ISO)/International Electrotechnical Committee (IEC): Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/66912.html (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Yao, Q.; Su, D.; Huang, M.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, M.; Lin, Q.; Xu, H.; Zeng, S. Residue degradation and metabolism of dinotefuran and cyromazine in Agrocybeaegerita: A risk assessment from cultivation to dietary exposure. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 127, 105951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO (World Health Organization). Inventory of Evaluations Performed by the Joint Meeting on Pesticide Residues (JMPR). 2025. Available online: http://apps.who.int/pesticide-residues-jmpr-database/Home/Range/All (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- European Commission. EU Pesticides Database. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/food/plant/pesticides/eu-pesticides-database/public/?event=homepage&language=EN (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Huang, Y.; Shi, T.; Luo, X.; Xiong, H.; Min, F.; Chen, Y.; Nie, S.; Xie, M. Determination of multi-pesticide residues in green tea with a modified QuEChERS protocol coupled to HPLC-MS/MS. Food Chem. 2019, 275, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Statement on the dietary risk assessment for the proposed temporary maximum residue level for chlormequat in oyster mushrooms. EFSA J. 2019, 17, e05707. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.Y.; Yu, X.W.; Fang, L. Organochlorine pesticide content and distribution in coastal seafoods in Zhoushan, Zhejiang Province. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014, 80, 288–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Dong, J.; Chen, M.; Tian, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, L.; Wu, Y.; Gong, Z. Dietary exposure and risk assessment of perchlorate in diverse food from Wuhan, China. Food Chem. 2021, 358, 129881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xu, W.; Ni, L.; Chen, H.; Hu, X.; Lin, H. Development of a sensitive simultaneous analytical method for 26 targeted mycotoxins in coix seed and Monte Carlo simulation-based exposure risk assessment for local population. Food Chem. 2024, 435, 137563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundhar, S.; Shakila, R.J.; Shalini, R.; Samraj, A.; Jayakumar, N.; Arisekar, U.; Surya, T. First report on the exposure and health risk assessment of organochlorine pesticide residues in Caulerpa racemosa, and their potential impact on household culinary processes. Food Res. Int. 2023, 174, 113559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makri, A.; Goveia, M.; Balbus, J.; Parkin, R. Children’s susceptibility to chemicals: A review by developmental stage. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health B 2004, 7, 417–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gavell, E.; De Lauzon-Guillain, B.; Charles, M.; Chevrier, C.; Hulin, M.; Sirot, V.; Merlo, M.; Nougadère, A. Chronic dietary exposure to pesticide residues and associated risk in the French ELFE cohort ofpregnant women. Environ. Int. 2016, 92–93, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mir, S.A.; Dar, B.; Shah, M.A.; Sofi, S.A.; Hamdani, A.M.; Oliveira, C.A.; Moosavi, M.H.; Khaneghah, A.M.; Sant’Ana, A.S. Application of new technologies in decontamination of mycotoxins in cereal grains: Challenges, and perspectives. Food Chem Toxicol. 2021, 148, 111976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). International Estimated Short-Term Intake. 2013. Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/food-safety/gems-food/guidance-iesti-2014.pdf?sfvrsn=9b24629a_2 (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Sieke, C. Probabilistic cumulative dietary risk assessment of pesticide residues in foods for the German population based on food monitoring data from 2009 to 2014. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 121, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Liu, M.; Wang, T.; Xu, H.; Liu, X.; Jiang, P.; Li, X.; Li, H.; Yang, J.; Nie, J. Occurrence, processing factors, and dietary risk assessment of multi-pesticides in cowpea. Food Control 2025, 171, 111145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, C.; Yu, H.; Cheng, Y.; Xie, Y.; Yao, W.; Guo, Y.; Qian, H. Chemical food contaminants during food processing: Sources and control. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 61, 1545–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Zhou, H.; McClements, D. Application of static in vitro digestion models for assessing the bioaccessibility of hydrophobic bioactives: A review. Trends Food Sci. Tech. 2022, 122, 314–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Q.; Wang, F.L.; Wang, X.X.; Chen, T.; Guo, X.T. Environmental toxicity and ecological effects of micro(nano)plastics: A huge challenge posed by biodegradability. TrAC-Trend. Anal. Chem. 2023, 164, 117092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-S.; Zhao, Y.-G.; Man, Y.-B.; Wong, C.K.C.; Wong, M.-H. Oral bioaccessibility and human risk assessment of organochlorine pesticides (OCPs) via fish consumption, using an in vitro gastrointestinal model. Food Chem. 2011, 127, 1673–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA. Guidance of the Scientific Committee on a request from EFSA related to Uncertainties in Dietary Exposure Assessment. EFSA J. 2006, 4, 438. [Google Scholar]

| PGRs | MOA | ADI (mg/kg bw/Day) | ARfD (mg/kg bw) | Registered for Cotton | Registered for Wheat | Registered for Corn | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paclobutrazo | inhibiting gibberellin synthesis | 0.022 | 0.1 | N | Y | N | 11/55/EU |

| Uniconazol | inhibiting gibberellin synthesis | 0.02 | N.A. | Y | Y | N | GB2763 |

| Chlormequa | inhibiting gibberellin synthesis | 0.04 | 0.09 | Y | Y | Y | EFSA08 |

| Mepiquat chloride | inhibiting gibberellin synthesis | 0.3 | 0.6 | Y | Y | Y | JMPR2023 |

| Thidiazuron | mimicking the effects of both auxin and cytokinin | 0.04 | N.A. | Y | Y | Y | GB2763 |

| Diethyl aminoethyl hexanoate | stimulating the synthesis of chlorophyll, protein, and nucleic acid | 0.023 | N.A. | Y | N | Y | GB2763 |

| Sodium nitrophenolate * | enhancing cell viability and facilitating cellular protoplasmic flow | 0.003 | N.A. | N | Y | N | GB2763 |

| Flumetrali | inhibitors of stem elongation and branching | 0.015 | 0.1 | Y | N | N | 2015/2105/EU |

| Diuron | disrupting plastoquinone-mediated electron transfer | 0.007 | 0.016 | Y | N | N | Dir 08/91 |

| Pyraflufen-ethyl | inhibiting protoporphyrinogen oxidase | 0.2 | 0.2 | Y | Y | N | 2016/182/EU |

| Pendimethalin | inhibiting mitosis | 0.1 | 1 | Y | N | Y | JMPR2016 |

| Mushroom (No. of Samples) | Pesticides | N > LOQ | Residual Levels (mg/kg) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | Mean | Median | |||

| A. aegerita (15) | Chlormequat | 8 (53.3%) | <LOD − 0.206 | 0.064 | 0.061 |

| Mepiquat chloride | 14 (93.3%) | <LOD − 4.611 | 1.602 | 0.351 | |

| Thidiazuron | 2 (13.3%) | <LOD − 0.054 | 0.006 | 0.000 | |

| Sodium nitrophenolate | 5 (33.3%) | <LOD − 0.267 | 0.052 | 0.000 | |

| A. auricula (15) | Sodium nitrophenolate | 12 (80.0%) | <LOD − 0.207 | 0.112 | 0.115 |

| L. edodes (15) | Chlormequat | 10 (66.7%) | <LOD − 0.074 | 0.041 | 0.054 |

| P. eryngii (15) | Chlormequat | 1 (6.7%) | <LOD − 0.044 | 0.003 | 0.000 |

| Thidiazuron | 1 (6.7%) | <LOD − 0.020 | 0.001 | 0.000 | |

| Sodium nitrophenolate | 4 (26.7%) | <LOD − 0.008 | 0.001 | 0.000 | |

| P. ostreatus (15) | Chlormequat | 9 (60.0%) | <LOD − 0.633 | 0.094 | 0.007 |

| Mepiquat chloride | 9 (60.0%) | <LOD − 2.466 | 0.358 | 0.059 | |

| Thidiazuron | 3 (20.0%) | <LOD − 0.050 | 0.008 | 0.000 | |

| Sodium nitrophenolate | 5 (33.3%) | <LOD − 0.093 | 0.008 | 0.000 | |

| T. fuciformis Berk (15) | Chlormequat | 15 (100%) | 0.156–2.812- | 1.135 | 1.261 |

| Mepiquat chloride | 12 (80.0%) | <LOD − 3.022 | 1.246 | 1.322 | |

| Sodium nitrophenolate | 10 (66.7%) | <LOD − 0.687 | 0.322 | 0.378 | |

| H. erinaceus (15) | Chlormequat | 12 (80.0%) | <LOD − 3.259 | 1.130 | 0.897 |

| Mepiquat chloride | 12 (80.0%) | <LOD − 6.308 | 2.600 | 3.113 | |

| Thidiazuron | 2 (13.3%) | <LOD − 0.212 | 0.026 | 0.000 | |

| Sodium nitrophenolate | 14 (93.3%) | <LOD − 0.647 | 0.479 | 0.502 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yao, Q.; Su, D.; Lin, X.; Xu, H.; Zheng, Y.; Xiao, Y. Plant Growth Regulator Residues in Edible Mushrooms: Are They Hazardous? Foods 2025, 14, 4098. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234098

Yao Q, Su D, Lin X, Xu H, Zheng Y, Xiao Y. Plant Growth Regulator Residues in Edible Mushrooms: Are They Hazardous? Foods. 2025; 14(23):4098. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234098

Chicago/Turabian StyleYao, Qinghua, Desen Su, Xiuxian Lin, Hui Xu, Yunyun Zheng, and Yuwei Xiao. 2025. "Plant Growth Regulator Residues in Edible Mushrooms: Are They Hazardous?" Foods 14, no. 23: 4098. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234098

APA StyleYao, Q., Su, D., Lin, X., Xu, H., Zheng, Y., & Xiao, Y. (2025). Plant Growth Regulator Residues in Edible Mushrooms: Are They Hazardous? Foods, 14(23), 4098. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234098