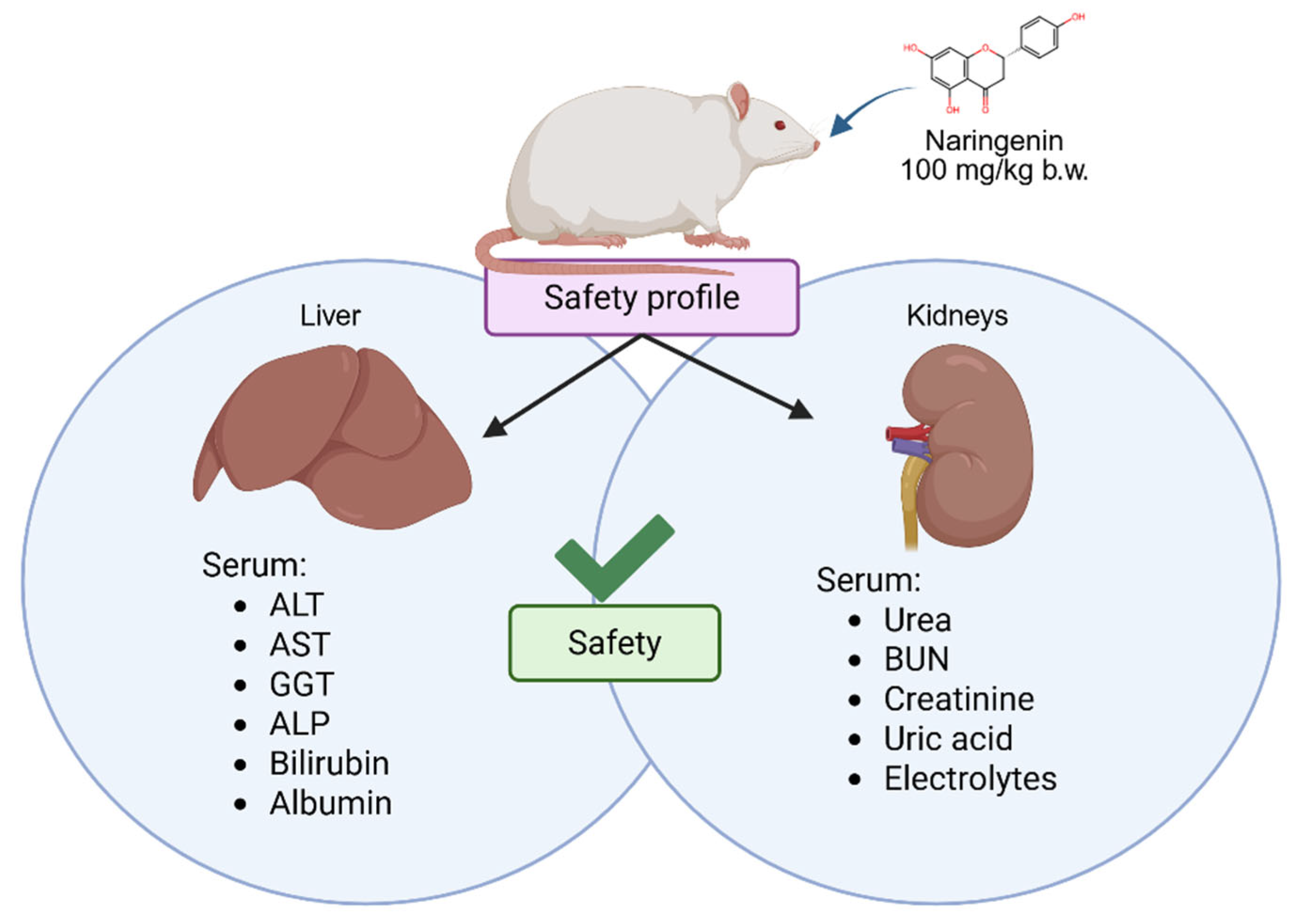

A 100 mg/kg Dose of Naringenin as an Anti-Obesity Agent for Eight Weeks Exerts No Apparent Hepatotoxic or Nephrotoxic Effects in Wistar Rats

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Statement

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Biochemical Analyses

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

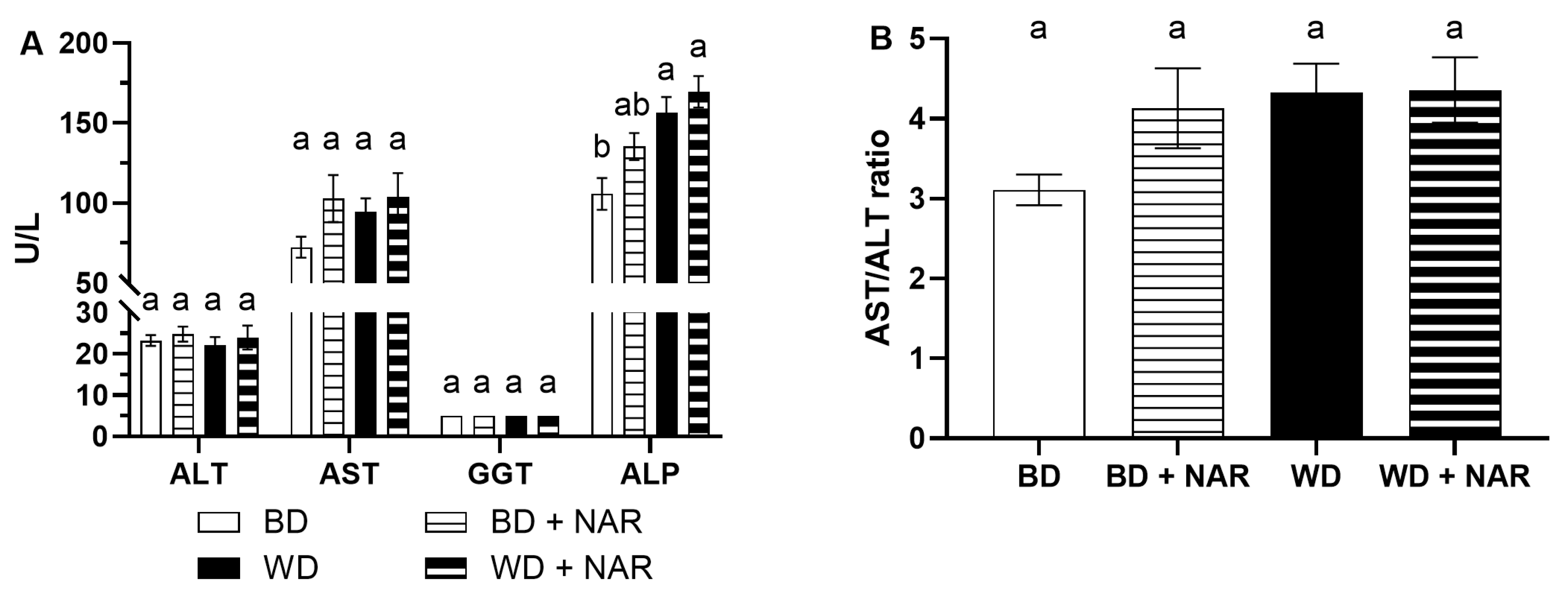

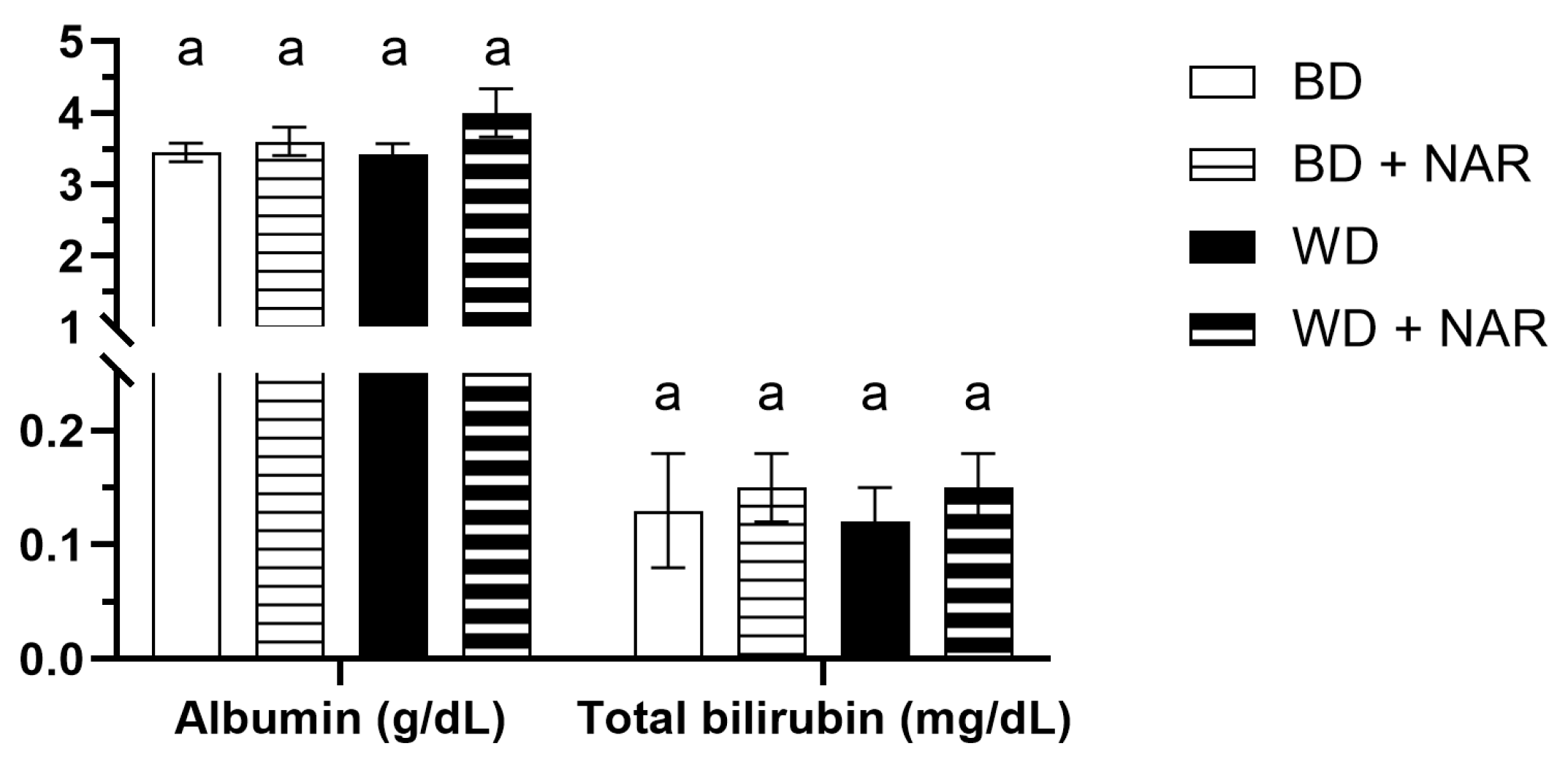

3.1. Biomarkers of Liver Function

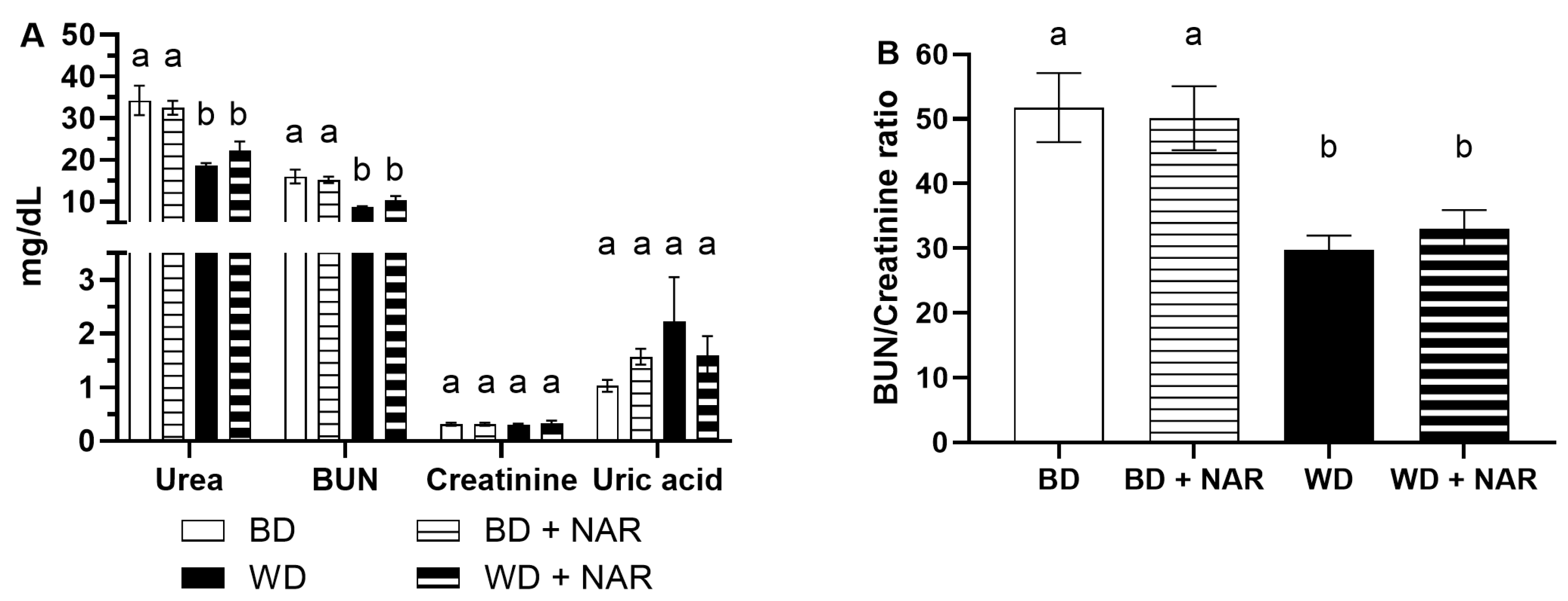

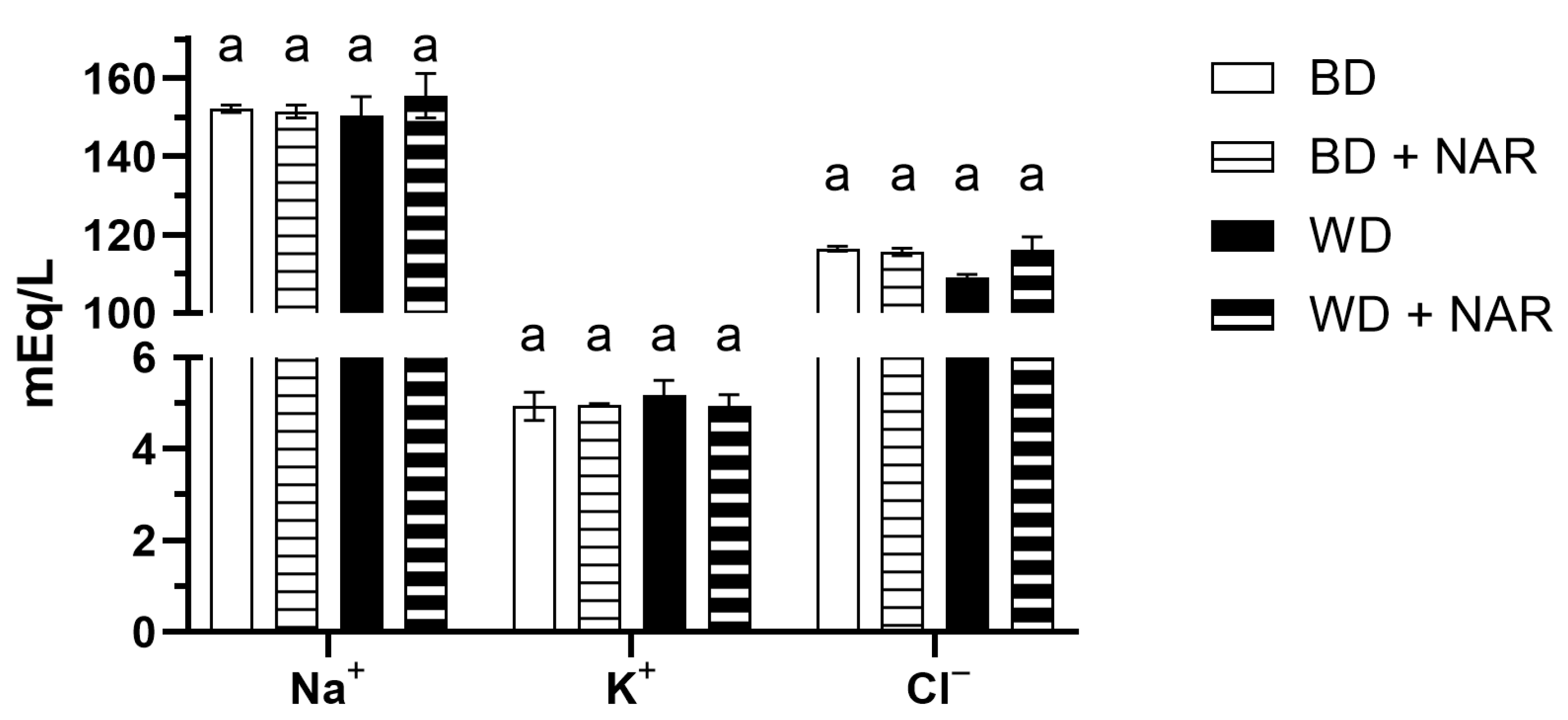

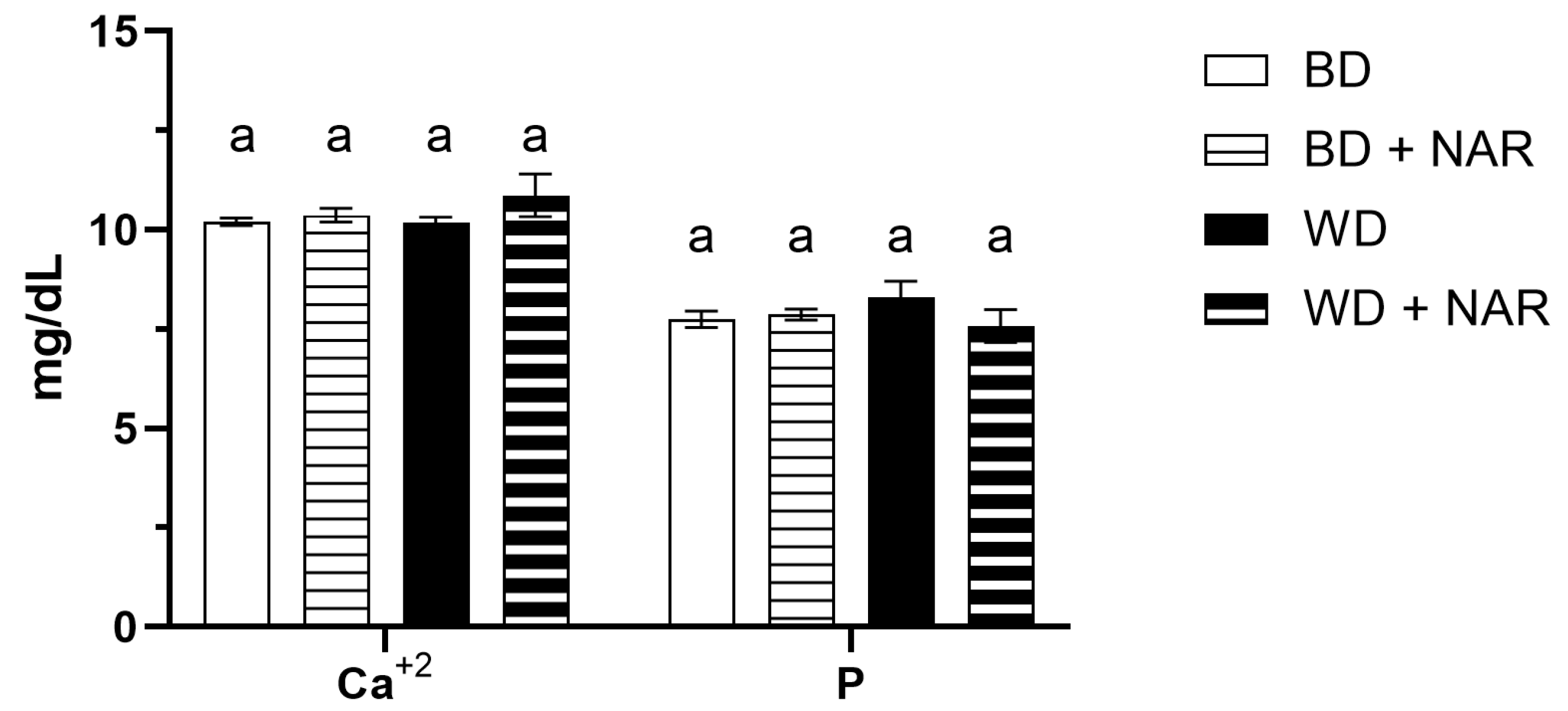

3.2. Biomarkers of Kidney Function

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WD | Western diet |

| ALT | Alanine aminotransferase |

| AST | Aspartate aminotransferase |

| GGT | Gamma-glutamyl transferase |

| ALP | Alkaline phosphatase |

| BUN | Blood urea nitrogen |

| BD | Basal diet |

| MAFLD | Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease |

| CMC | Carboxymethylcellulose |

| DILI | Drug-induced liver injury |

| NAFLD | Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease |

| HFHFD | High-fat high-fructose diet |

| HED | Human equivalent dose |

References

- Phelps, N.H.; Singleton, R.K.; Zhou, B.; Heap, R.A.; Mishra, A.; Bennett, J.E.; Paciorek, C.J.; Lhoste, V.P.; Carrillo-Larco, R.M.; Stevens, G.A.; et al. Worldwide trends in underweight and obesity from 1990 to 2022: A pooled analysis of 3663 population-representative studies with 222 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet 2024, 403, 1027–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edin, C.; Ekstedt, M.; Scheffel, T.; Karlsson, M.; Swahn, E.; Östgren, C.J.; Engvall, J.; Ebbers, T.; Leinhard, O.D.; Lundberg, P.; et al. Ectopic fat is associated with cardiac remodeling—A comprehensive assessment of regional fat depots in type 2 diabetes using multi-parametric MRI. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 813427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Wang, Y.; Chen, F.; Zhou, B. Epigenetics in obesity: Mechanisms and advances in therapies based on natural products. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2024, 12, e1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eng, J.Y.; Moy, F.M.; Bulgiba, A.; Rampal, S. Dose–response relationship between western diet and being overweight among teachers in Malaysia. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Beltrán-Velasco, A.I.; Redondo-Flórez, L.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. Global impacts of western diet and its effects on metabolism and health: A narrative review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, V.; Sundaresan, A.; Shishodia, S. Overnutrition and lipotoxicity: Impaired efferocytosis and chronic inflammation as precursors to multifaceted disease pathogenesis. Biology 2024, 13, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cena, H.; Calder, P.C. Defining a healthy diet: Evidence for the role of contemporary dietary patterns in health and disease. Nutrients 2020, 12, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaouhari, Y.; Disca, V.; Ferreira-Santos, P.; Alvaredo-López-Vizcaíno, A.; Travaglia, F.; Bordiga, M.; Locatelli, M. Valorization of date fruit (Phoenix dactylifera L.) as a potential functional food and ingredient: Characterization of fiber, oligosaccharides, and antioxidant polyphenols. Molecules 2024, 29, 4606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Almada, G.; Domínguez-Avila, J.A.; Robles-Sánchez, R.M.; Arauz-Cabrera, J.; Martínez-Coronilla, G.; González-Aguilar, G.A.; Salazar-López, N.J. Naringenin decreases retroperitoneal adiposity and improves metabolic parameters in a rat model of western diet-induced obesity. Metabolites 2025, 15, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tareq, F.S.; Singh, J.; Ferreira, J.F.S.; Sandhu, D.; Suarez, D.L.; Luthria, D.L. A targeted and an untargeted metabolomics approach to study the phytochemicals of tomato cultivars grown under different salinity conditions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 7694–7706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, N.; Hassan, H.; Abdallah, H.; Afifi, S.; Elgamal, A.; Farrag, A.; El-Gendy, A.; Farag, M.; Elshamy, A. Protective effects of naringenin from Citrus sinensis (var. Valencia) peels against CCl4-induced hepatic and renal injuries in rats assessed by metabolomics, histological and biochemical analyses. Nutrients 2022, 14, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhao, H.; Che, J.; Yao, W. Naringenin alleviates obesity-associated hypertension by reducing hyperlipidemia and oxidative stress. Kidney Blood Press. Res. 2022, 47, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeini, F.; Namkhah, Z.; Tutunchi, H.; Rezayat, S.M.; Mansouri, S.; Yaseri, M.; Hosseinzadeh-Attar, M.J. Effects of naringenin supplementation on cardiovascular risk factors in overweight/obese patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A pilot double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 34, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, H.; Liu, S.; Liu, G.; Chen, H.; Kang, J.; Wang, H. Naringenin inhibits lipid accumulation by activating the AMPK pathway in vivo and vitro. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2023, 12, 1174–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuhako, R.; Yoshida, H.; Sugita, C.; Kurokawa, M. Naringenin suppresses neutrophil infiltration into adipose tissue in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. J. Nat. Med. 2020, 74, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfwuaires, M.A.; Famurewa, A.C.; Algefare, A.I.; Sedky, A. Naringenin blocks hepatic cadmium accumulation and suppresses cadmium-induced hepatotoxicity via amelioration of oxidative inflammatory signaling and apoptosis in rats. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 2024, 47, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, T.; Lee, Y.M.; Takimoto, E.; Ueda, K.; Liu, P.Y.; Shen, H.H. Inhibitory effects of naringenin on estrogen deficiency-induced obesity via regulation of mitochondrial dynamics and AMPK activation associated with white adipose tissue browning. Life Sci. 2024, 340, 122453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Ou, Y.; Hu, G.; Wen, C.; Yue, S.; Chen, C.; Xu, L.; Xie, J.; Dai, H.; Xiao, H.; et al. Naringenin attenuates non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by down-regulating the NLRP3/NF-κB pathway in mice. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 177, 1806–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.; Xin, M.; Liang, S.; Huang, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, C.; Liu, C.; Song, X.; Sun, J.; Sun, W. Naringenin ameliorates hyperuricemia by regulating renal uric acid excretion via the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway and renal inflammation through the NF-κB signaling pathway. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 1434–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Peng, W.; Yang, C.; Zou, W.; Liu, M.; Wu, H.; Fan, L.; Li, P.; Zeng, X.; Su, W. Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of naringin and active metabolite naringenin in rats, dogs, humans, and the differences between species. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez-Cuevas, J.; Santos, A.; Armendariz-Borunda, J. Pathophysiological molecular mechanisms of obesity: A link between MAFLD and NASH with cardiovascular diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.A.M.; Abdel-Ghaffar, O.; Aly, D.A.M. The protective effect of naringenin against pyrazinamide-induced hepatotoxicity in male wistar rats. J. Basic. Appl. Zool. 2022, 83, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Chen, J.; Zhang, T.; Yuan, X.; Ge, A.; Wang, S.; Xu, H.; Zeng, L.; Ge, J. Efficacy and safety of dietary polyphenol supplementation in the treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 949746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godala, M.; Gaszyńska, E.; Walczak, K.; Małecka-Wojciesko, E. Evaluation of albumin, transferrin and transthyretin in inflammatory bowel disease patients as disease activity and nutritional status biomarkers. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, J.R.; Machado, M.V. New insights about albumin and liver disease. Ann. Hepatol. 2018, 17, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedermann, C.J.; Wiedermann, W.; Joannidis, M. Correction to: Hypoalbuminemia and acute kidney injury: A meta-analysis of observational clinical studies. Intensive Care Med. 2021, 47, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Singh, T.G. Drug induced nephrotoxicity- A mechanistic approach. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2023, 50, 6975–6986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadahunsi, O.S.; Olorunnisola, O.S. High-salt–fat diet: A risk factor for elevated blood pressure associated with dyslipidemia, perturbation in cardio-renal anti-oxidant and pro-inflammatory status in Wistar rats. J. Basic. Appl. Zool. 2024, 85, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roza, N.A.V.; Possignolo, L.F.; Palanch, A.C.; Gontijo, J.A.R. Effect of long-term high-fat diet intake on peripheral insulin sensibility, blood pressure, and renal function in female rats. Food Nutr. Res. 2016, 60, 28536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, F.; Paié-Ribeiro, J.; Almeida, M.; Barros, A.N. Exploring the role of phenolic compounds in chronic kidney disease: A systematic review. Molecules 2024, 29, 2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolini, D.G.; Maciel, G.M.; Fernandes, I.A.A.; Rossetto, R.; Brugnari, T.; Ribeiro, V.R.; Haminiuk, C.W.I. Biological potential and technological applications of red fruits: An overview. Food Chem. Adv. 2021, 1, 100014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichardt, F.; Chassaing, B.; Nezami, B.G.; Li, G.; Tabatabavakili, S.; Mwangi, S.; Uppal, K.; Liang, B.; Vijay-Kumar, M.; Jones, D.; et al. Western diet induces colonic nitrergic myenteric neuropathy and dysmotility in mice via saturated fatty acid- and lipopolysaccharide-induced TLR4 signalling. J. Physiol. 2017, 595, 1831–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. FDA (Food and Drug Administration). 21 C.F.R. § 101.9(c)(1)(i)(C): Nutrition Labeling of Food. Code of Federal Regulations. 2025. Available online: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-21/chapter-I/subchapter-B/part-101/subpart-B/section-101.9 (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Patel, S.; Patel, S.; Kotadiya, A.; Patel, S.; Shrimali, B.; Joshi, N.; Patel, T.; Trivedi, H.; Patel, J.; Joharapurkar, A.; et al. Age-related changes in hematological and biochemical profiles of Wistar rats. Lab. Anim. Res. 2024, 40, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boehm, O.; Zur, B.; Koch, A.; Tran, N.; Freyenhagen, R.; Hartmann, M.; Zacharowski, K. Clinical chemistry reference database for Wistar rats and C57/BL6 mice. Biol. Chem. 2007, 388, 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros-Ramírez, R.; Lasso, P.; Urueña, C.; Saturno, J.; Fiorentino, S. Assessment of acute and chronic toxicity in wistar rats (Rattus norvegicus) and New Zealand rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) of an enriched polyphenol extract obtained from Caesalpinia spinosa. J. Toxicol. 2024, 2024, 3769933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, S.M.; Varma, A.; Kumar, S.; Acharya, S.; Patil, R. Navigating disease management: A comprehensive review of the de ritis ratio in clinical medicine. Cureus 2024, 16, e64447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houtmeyers, A.; Duchateau, L.; Grünewald, B.; Hermans, K. Reference intervals for biochemical blood variables, packed cell volume, and body temperature in pet rats (Rattus norvegicus) using point-of-care testing. Vet. Clin. Pathol. 2016, 45, 669–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchino, S.; Bellomo, R.; Goldsmith, D. The meaning of the blood urea nitrogen/creatinine ratio in acute kidney injury. Clin. Kidney J. 2012, 5, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Lee, D.W.; Lee, S.B.; Kwak, I.S. The role of uric acid in kidney fibrosis: Experimental evidences for the causal relationship. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 638732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feig, D.I.; Kang, D.H.; Nakagawa, T.; Mazzali, M.; Johnson, R.J. Uric acid and hypertension. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2006, 8, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustine, C.; Khobe, D.; Babakiri, Y.; Igwebuike, J.U.; Joel, I.; John, T.; Ibrahim, A. Blood parameters of wistar albino rats fed processed tropical sickle pod (Senna obtusifolia) leaf meal-based diets. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2020, 4, 778–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamber, S.S.; Bansal, P.; Sharma, S.; Singh, R.B.; Sharma, R. Biomarkers of liver diseases. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2023, 50, 7815–7823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, A.Z.; Alhazzani, K.; Alrewily, S.Q.; Aljerian, K.; Algahtani, M.M.; Alqahtani, Q.H.; Haspula, D.; Alhamed, A.S.; Alqinyah, M.; Raish, M. The potential protective role of naringenin against dasatinib-induced hepatotoxicity. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.; Yokoyama, D.; Matsuura, C.; Kondo, K.; Shimazaki, T.; Ryoke, K.; Kobayashi, A.; Sakakibara, H. Active-phase plasma alkaline phosphatase isozyme activity is a sensitive biomarker for excessive fructose intake. In Vivo 2023, 37, 1967–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohrabi, M.; Aghapour, S.; Khoonsari, M.; Ajdarkosh, H.; Nobakht, H.; Zamani, F.; Nikkhah, M. Serum alkaline phosphate level associates with metabolic syndrome components regardless of non-alcoholic fatty liver; a population-based study in northern Iran. Middle East. J. Dig. Dis. 2023, 15, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A.H.; Petroski, G.F.; Diaz-Arias, A.A.; Juboori, A.A.; Wheeler, A.A.; Ganga, R.R.; Pitt, J.B.; Spencer, N.M.; Hammoud, G.M.; Rector, R.S.; et al. A model incorporating serum alkaline phosphatase for prediction of liver fibrosis in adults with obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, L.; Zhang, X.; Tian, H.; Jin, X.; Fan, H.; Wang, N.; Sun, J.; Li, D.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; et al. Prevalence and risk factors of metabolic-associated fatty liver disease during 2014-2018 from three cities of Liaoning province: An epidemiological survey. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e047588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, M.T.; Gentile, C.L.; Cox-York, K.; Wei, Y.; Wang, D.; Estrada, A.L.; Reese, L.; Miller, T.; Pagliassotti, M.J.; Weir, T.L. Fuzhuan tea consumption imparts hepatoprotective effects and alters intestinal microbiota in high saturated fat diet-fed rats. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2016, 60, 1213–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Yu, B.; Chen, D.; Mao, X.; Zheng, P.; Luo, J.; He, J. Dietary chlorogenic acid improves growth performance of weaned pigs through maintaining antioxidant capacity and intestinal digestion and absorption function. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 96, 1108–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroutanfar, A.; Mehri, S.; Kamyar, M.; Tandisehpanah, Z.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Protective effect of punicalagin, the main polyphenol compound of pomegranate, against acrylamide-induced neurotoxicity and hepatotoxicity in rats. Phytother. Res. 2020, 34, 3262–3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almundarij, T.I.; Alharbi, Y.M.; Abdel-Rahman, H.A.; Barakat, H. Antioxidant activity, phenolic profile, and nephroprotective potential of Anastatica hierochuntica ethanolic and aqueous extracts against CCl4-induced nephrotoxicity in rats. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahramanoğullari, M.; Erişir, M.; Yaman, M.; Parlak, A.T. Effects of naringenin on oxidative damage and apoptosis in liver and kidney in rats subjected to chronic mercury chloride. Environ. Toxicol. 2024, 39, 2937–2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.; Fu, J.; Zhang, F.; Cai, Y.; Wu, G.; Ma, W.; Zhou, H.; He, Y. The association between BMI and serum uric acid is partially mediated by gut microbiota. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e01140-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yustisia, I.; Tandiari, D.; Cangara, M.H.; Hamid, F.; Daud, N.A.S. A high-fat, high-fructose diet induced hepatic steatosis, renal lesions, dyslipidemia, and hyperuricemia in non-obese rats. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herman, M.A.; Birnbaum, M.J. Molecular aspects of fructose metabolism and metabolic disease. Cell Metab. 2021, 33, 2329–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badary, O.A.; Abdel-Maksoud, S.; Ahmed, W.A.; Owieda, G.H. Naringenin attenuates cisplatin nephrotoxicity in rats. Life Sci. 2025, 76, 2125–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellavite, P. Neuroprotective potentials of flavonoids: Experimental studies and mechanisms of action. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. FDA (Food and Drug Administration). Guidance for Industry: Estimating the Maximum Safe Starting Dose in Initial Clinical Trials for Therapeutics in Adult Healthy Volunteers. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/72309/download (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Rebello, C.J.; Beyl, R.A.; Lertora, J.J.L.; Greenway, F.L.; Ravussin, E.; Ribnicky, D.M.; Poulev, A.; Kennedy, B.J.; Castro, H.F.; Campagna, S.R.; et al. Safety and pharmacokinetics of naringenin: A randomized, controlled, single-ascending-dose clinical trial. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2020, 22, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedeji, A.O.; Sonee, M.; Chen, Y.; Lynch, K.; Peron, K.; King, N.; McDuffie, J.E.; Vinken, P. Evaluation of novel urinary biomarkers in beagle dogs with amphotericin b-induced kidney injury. Int. J. Toxicol. 2023, 42, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, L.C.C.; Cruz, A.G.; Camargo, F.N.; Sucupira, F.G.; Moreira, G.V.; Matos, S.L.; Amaral, A.G.; Murata, G.M.; Carvalho, C.R.O.; Camporez, J.P. Estradiol Protects Female ApoE KO Mice against Western-Diet-Induced Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, R.; Garver, H.; Harkema, J.R.; Galligan, J.J.; Fink, J.D.; Xu, H. Sex Differences in Renal Inflammation and Injury in High-Fat Diet–Fed Dahl Salt-Sensitive Rats. Hypertension 2018, 72, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juszczak, F.; Pierre, L.; Decarnoncle, M.; Jadot, I.; Martin, B.; Botton, O.; Caron, N.; Dehairs, J.; Swinnen, J.V.; Declèves, A.E. Sex differences in obesity-induced renal lipid accumulation revealed by lipidomics: A role of adiponectin/AMPK axis. Biol. Sex. Differ. 2023, 14, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

López-Almada, G.; Domínguez-Avila, J.A.; González-Aguilar, G.A.; Robles-Sánchez, R.M.; Salazar-López, N.J. A 100 mg/kg Dose of Naringenin as an Anti-Obesity Agent for Eight Weeks Exerts No Apparent Hepatotoxic or Nephrotoxic Effects in Wistar Rats. Foods 2025, 14, 4083. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234083

López-Almada G, Domínguez-Avila JA, González-Aguilar GA, Robles-Sánchez RM, Salazar-López NJ. A 100 mg/kg Dose of Naringenin as an Anti-Obesity Agent for Eight Weeks Exerts No Apparent Hepatotoxic or Nephrotoxic Effects in Wistar Rats. Foods. 2025; 14(23):4083. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234083

Chicago/Turabian StyleLópez-Almada, Gabriela, J. Abraham Domínguez-Avila, Gustavo A. González-Aguilar, Rosario Maribel Robles-Sánchez, and Norma Julieta Salazar-López. 2025. "A 100 mg/kg Dose of Naringenin as an Anti-Obesity Agent for Eight Weeks Exerts No Apparent Hepatotoxic or Nephrotoxic Effects in Wistar Rats" Foods 14, no. 23: 4083. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234083

APA StyleLópez-Almada, G., Domínguez-Avila, J. A., González-Aguilar, G. A., Robles-Sánchez, R. M., & Salazar-López, N. J. (2025). A 100 mg/kg Dose of Naringenin as an Anti-Obesity Agent for Eight Weeks Exerts No Apparent Hepatotoxic or Nephrotoxic Effects in Wistar Rats. Foods, 14(23), 4083. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234083