Clarifying the Dual Role of Staphylococcus spp. in Cheese Production

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Coagulase-Positive Staphylococci (CoPS)

2.1. Staphylococcus aureus

2.2. Other Coagulase-Positive Staphylococci (CoPS)

3. Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci (CoNS)

Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) Status

4. Virulence Factors

4.1. Biofilm Formation

4.2. Antibiotic Resistance

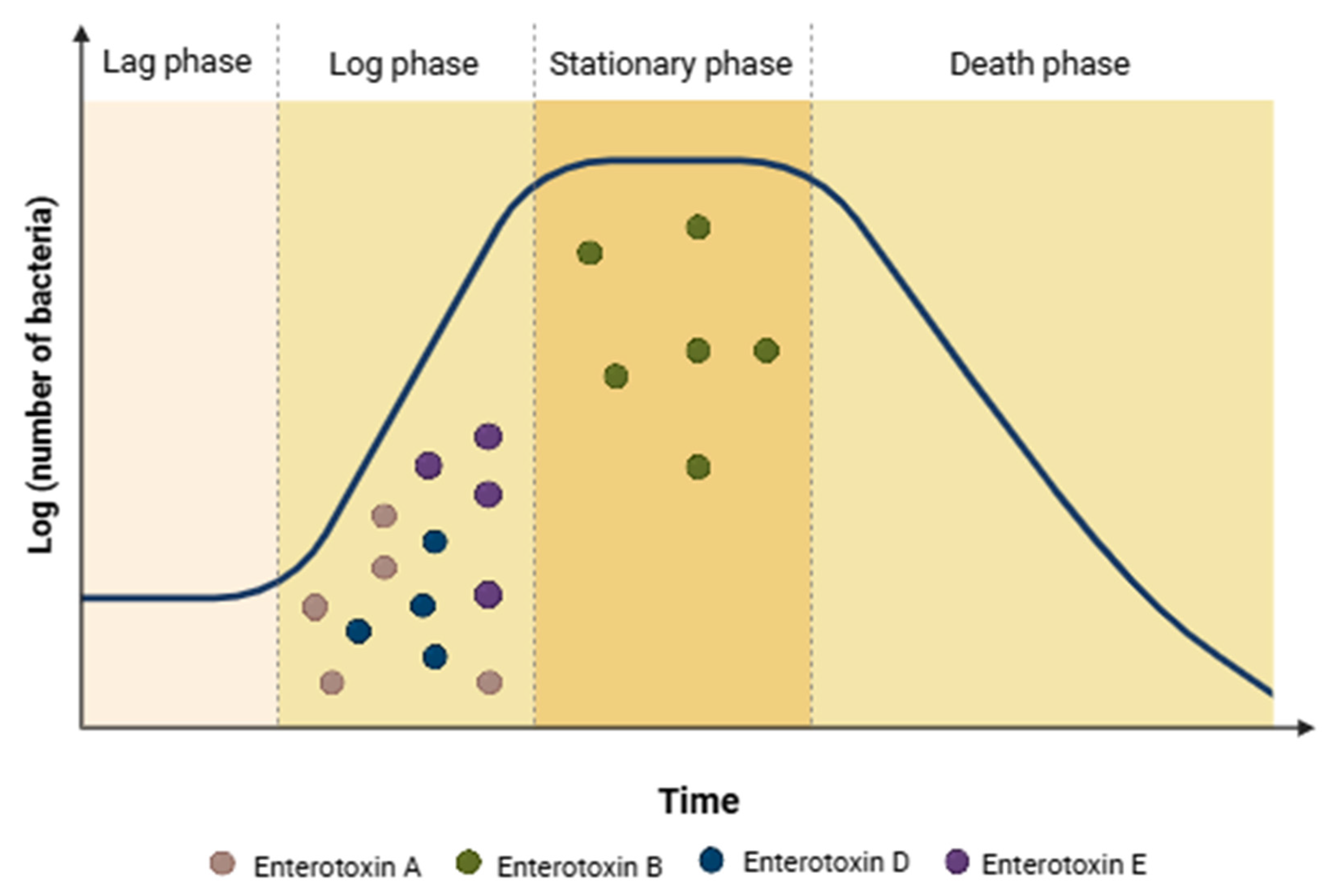

4.3. Expression of Enterotoxins Genes

5. Staphylococcal Food Poisoning (SFP) from Cheese Consumption

6. Control of Staphylococcus in Cheeses

Emerging Control Strategies

7. Microbiological Criteria for Staphylococcus and Enterotoxins in Cheeses

8. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Aap | Accumulation-associated protein |

| AMR | Antimicrobial resistance |

| ANVISA | National Agency for Sanitary Vigilance |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| AIP | Autoinducing peptide |

| Aw | Water activity |

| BAM | Bacteriological Analytical Manual |

| Bap | Biofilm-associated protein |

| CMT | California mastitis test |

| CIP | Cleaning-in-place |

| ClfA/ClfB | Clumping factors |

| CoNS | Coagulase-negative staphylococci |

| CoPS | Coagulase-positive staphylococci |

| CoVS | Coagulase-variable staphylococci |

| ECDC | European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control |

| EFSA | European Food Safety Authority |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| EPS | Extracellular polymeric substance |

| ET | Exfoliative toxin |

| EU/EEA | European Union/European Economic Area |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| Fib | Fibrinogen-binding protein |

| FnBP | Fibronectin-binding protein |

| GISA | Intermediate-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus to glycopeptides |

| GI | Genomic island |

| GMP | Good manufacturing practices |

| GRAS | Generally recognized as safe |

| HACCP | Hazard analysis and critical control points |

| LA-MRSA | Livestock-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| MAR | Multiple antibiotic resistance |

| MDR | Multidrug-resistant |

| MRCNS | Methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococci |

| MRSA | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| MRSP | Methicillin-resistant strains |

| MSSA | Methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus |

| MSCRAMMs | Microbial surface components recognizing adhesive matrix molecules |

| NaCl | Sodium chloride |

| PIA | Polysaccharide intercellular adhesion |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| PNAG | Poly-N-acetylglucosamine |

| Pls | Plasmin-sensitive protein |

| PSM | Phenol-soluble modulin |

| PVL | Panton-Valentine leukocidin |

| qPCR | Quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| SasC/SasG | Staphylococcus aureus surface proteins |

| SCCmec | Staphylococcal chromosomal cassette mec |

| SE | Staphylococcal enterotoxin |

| SEl | Staphylococcal enterotoxin-like protein |

| SFP | Staphylococcal food poisoning |

| SrrAB | Staphylococcal respiratory response regulator |

| SSSS | Staphylococcal scalded skin |

References

- Silva, N.; Taniwaki, M.H.; Junqueira, V.C.A.; Silveira, N.; Okazaki, M.M.; Gomes, R.A.R. Microbiological Examination Methods of Food and Water, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, E.; Draper, L.A.; Ross, R.P.; Hill, C. The advantages and challenges of using endolysins in a clinical setting. Viruses 2021, 13, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G.Y.C.; Bae, J.S.; Otto, M. Pathogenicity and virulence of Staphylococcus aureus. Virulence 2021, 12, 547–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Martín, M.; Corbera, J.A.; Suárez-Bonnet, A.; Tejedor-Junco, M.T. Virulence factors in coagulase-positive staphylococci of veterinary interest other than Staphylococcus aureus. Vet. Q. 2020, 40, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, K.; David, M.Z.; Skov, R.L. Staphylococcus, Micrococcus, and other catalase—Positive cocci. In Manual of Clinical Microbiology, 13th ed.; ASM Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, C.; Harsha, P.; Gupta, S.; Roy, S. Isolation and characterization of bacterial isolates from agricultural soil at drug district. Indian J. Sci. Res. 2014, 4, 221–226. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Taxonomy Browser: Staphylococcus. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/Browser/wwwtax.cgi?mode=info&id=1279 (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Grice, E.A.; Segre, J.A. The skin microbiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 9, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, T.J. Staphylococcus aureus—Molecular. In Encyclopedia of Dairy Sciences, 3rd ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova, C.; Iselin, L.; von Steiger, N.; Droz, S.; Sendi, P. Staphylococcus hyicus bacteremia in a farmer. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2011, 49, 4377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, N.; Junqueira, V.C.A.; Silveira, N.F.A.; Taniwaki, M.H.; Gomes, R.A.R.; Okazaki, M.M. Manual de Métodos de Análise Microbiológica de Alimentos e Água, 5th ed.; Blucher: São Paulo, Brazil, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Santiago, M.C.L. Pesquisa de Staphylococcus Coagulase Positiva Produtor da Toxina 1 da Síndrome do Choque tóxico (TSST-1) em Amostras de Queijo Minas Artesanal. Bachelor’s Thesis, Federal University of Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, R.W.; Hait, J.M.; Tallent, S.M. Staphylococcus aureus. In Guide to Foodborne Pathogens, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, M.; Kobayashi, N.; Nagashima, S.; Ishino, M.; Otokozawa, S.; Mise, K.; Sumi, A.; Tsutsumi, H.; Uehara, N.; Watanabe, N.; et al. Diversity of staphylocoagulase and identification of novel variants of staphylocoagulase gene in Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiol. Immunol. 2008, 52, 334–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, M.T.; Lauderdale, T.L.; Chou, C.C. Characteristics and virulence factors of livestock-associated ST9 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus with a novel recombinant staphylocoagulase type. Vet. Microbiol. 2013, 162, 779–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shittu, A.O.; Lin, J. Antimicrobial susceptibility patterns and characterization of clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus in KwaZulu-Natal province, South Africa. BMC Infect. Dis. 2006, 6, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velázquez-Guadarrama, N.; Olivares-Cervantes, A.L.; Salinas, E.; Martínez, L.; Escorcia, M.; Oropeza, R.; Rosas, I. Presence of environmental coagulase-positive staphylococci, their clonal relationship, resistance factors and ability to form biofilm. Rev. Argent. Microbiol. 2017, 49, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foronda-García-Hidalgo, C. Staphylococcus and other catalase-positive cocci. In Encyclopedia of Infection and Immunity; Rezaei, N., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhaiyan, M.; Wirth, J.S.; Saravanan, V.S. Phylogenomic analyses of the Staphylococcaceae family suggest the reclassification of five species within the genus Staphylococcus as heterotypic synonyms, the promotion of five subspecies to novel species, the taxonomic reassignment of five Staphylococcus species to Mammaliicoccus gen. nov., and the formal assignment of Nosocomiicoccus to the family Staphylococcaceae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2020, 70, 5926–5936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Loir, Y.; Baron, F.; Gautier, M. Staphylococcus aureus and food poisoning. Genet. Mol. Res. 2003, 2, 63–76. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12917803/ (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Jay, J.M.; Loessner, M.J.; Golden, D.A. Staphylococcal gastroenteritis. In Modern Food Microbiology, 7th ed.; Springer Science and Business Media, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, E.; Boyd, A.; Woods, K. Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 2765–2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grispoldi, L.; Karama, M.; Armani, A.; Hadjicharalambous, C.; Cenci-Goga, B.T. Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxin in food of animal origin and staphylococcal food poisoning risk assessment from farm to table. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2021, 20, 677–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, D.; Borges, A.; Simões, M. Staphylococcus aureus toxins and their molecular activity in infectious diseases. Toxins 2018, 10, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, M. Methicillin-resistant staphylococci. J. Clin. Pathol. 1961, 14, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, S.J.; Wylam, M.E. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection and treatment options. In Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Protocols; Ji, Y., Ed.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Volume 2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morosini, M.I.; Cercenado, E.; Ardanuy, C.; Torres, C. Detección fenotípica de mecanismos de resistencia en microorganismos grampositivos. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 2012, 30, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefani, S.; Varaldo, P.E. Epidemiology of methicillin-resistant staphylococci in Europe. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2003, 9, 1179–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassini, A.; Högberg, L.D.; Plachouras, D.; Quattrocchi, A.; Hoxha, A.; Simonsen, G.S.; Colomb-Cotinat, M.; Kretzschmar, M.E.; Devleesschauwer, B.; Cecchini, M.; et al. Attributable deaths and disability-adjusted life-years caused by infections with antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the EU and the European Economic Area in 2015: A population-level modelling analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance in Europe. Annual Report of the European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network (EARS-Net) 2017; ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2018.

- Ferrasso, M.M.; Gonzalez, H.L.; Timm, C.D. Staphylococcus hyicus. Arq. Inst. Biol. 2015, 82, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food Standards Australia New Zealand. Staphylococcus aureus; Food Standards Australia New Zealand: Canberra, Australia, 2013. Available online: https://www.foodstandards.gov.au/sites/default/files/publications/Documents/Staphylococcus%20aureus.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Khambaty, F.M.; Bennett, R.W.; Shah, D.B. Application of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis to the epidemiological characterization of Staphylococcus intermedius implicated in a food-related outbreak. Epidemiol. Infect. 1994, 113, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruscher, C.; Lübke-Becker, A.; Wleklinski, C.G.; Şoba, A.; Wieler, L.H.; Walther, B. Prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius isolated from clinical samples of companion animals and equidaes. Vet. Microbiol. 2009, 136, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, C.B.; Botoni, L.S.; Coura, F.M.; Silva, R.O.; dos Santos, R.D.; Heinemann, M.B.; Costa-Val, A.P. Frequency and antimicrobial susceptibility of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in dogs with otitis externa. Cienc. Rural 2018, 48, e20170738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devriese, L.A.; Hermans, K.; Baele, M.; Haesebrouck, F. Staphylococcus pseudintermedius versus Staphylococcus intermedius. Vet. Microbiol. 2009, 133, 206–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, T.; Kikuchi, K.; Tanaka, Y.; Takahashi, N.; Kamata, S.; Hiramatsu, K. Reclassification of phenotypically identified Staphylococcus intermedius strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007, 45, 2770–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, D.O.; Rook, K.A.; Shofer, F.S.; Rankin, S.C. Screening of Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus intermedius and Staphylococcus schleiferi isolates obtained from small companion animals for antimicrobial resistance: A retrospective review of 749 isolates (2003–2004). Vet. Dermatol. 2006, 17, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, D.C.; Holden, M.T.; Tong, S.Y.; Castillo-Ramirez, S.; Clarke, L.; Quail, M.A.; Currie, B.J.; Parkhill, J.; Bentley, S.D.; Feil, E.J.; et al. A very early-branching Staphylococcus aureus lineage lacking the carotenoid pigment staphyloxanthin. Genome Biol. Evol. 2011, 3, 881–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaumburg, F.; Alabi, A.S.; Köck, R.; Mellmann, A.; Kremsner, P.G.; Boesch, C.; Becker, K.; Leendertz, F.H.; Peters, G. Highly divergent Staphylococcus aureus isolates from African non-human primates. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2012, 4, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Ferreri, M.; Yu, F.; Liu, X.; Chen, L.; Su, J.; Han, B. Molecular types and antibiotic resistance of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from bovine mastitis in a single herd in China. Vet. J. 2012, 192, 550–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoaib, M.; Xu, J.; Meng, X.; Wu, Z.; Hou, X.; He, Z.; Shang, R.; Zhang, H.; Pu, W. Molecular epidemiology and characterization of antimicrobial-resistant Staphylococcus haemolyticus strains isolated from dairy cattle milk in Northwest, China. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1183390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammer, P.; Jordan, J.; Jacobs, C.; Klempt, M. Characterization of coagulase-negative staphylococci from brining baths in Germany. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 8734–8744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morot-Bizot, S.C.; Leroy, S.; Talon, R. Staphylococcal community of a small unit manufacturing traditional dry fermented sausages. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2006, 108, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artini, M.; Papa, R.; Scoarughi, G.L.; Galano, E.; Barbato, G.; Pucci, P.; Selan, L. Comparison of the action of different proteases on virulence properties related to the staphylococcal surface. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2013, 114, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zell, C.; Resch, M.; Rosenstein, R.; Albrecht, T.; Hertel, C.; Götz, F. Characterization of toxin production of coagulase-negative staphylococci isolated from food and starter cultures. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2008, 127, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, S.; Lee, J.H.; Jeong, D.W. Food-derived coagulase-negative Staphylococcus as starter cultures for fermented foods. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 29, 1023–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, P.B.; Reed, P.; Monteiro, J.M.; Pinho, M.G. Revisiting the role of VraTSR in Staphylococcus aureus response to cell wall-targeting antibiotics. J. Bacteriol. 2022, 204, e00162-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajewska, J.; Zakrzewski, A.; Chajęcka-Wierzchowska, W.; Zadernowska, A. Meta-analysis of the global occurrence of S. aureus in raw cattle milk and artisanal cheeses. Food Control 2023, 147, 109603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, B.; Garriga, M.; Hugas, M.; Bover-Cid, S.; Veciana-Nogués, M.T.; Aymerich, T. Molecular, technological and safety characterization of Gram-positive catalase-positive cocci from slightly fermented sausages. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2006, 107, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, A.M. Antimicrobial resistance and heat sensitivity of oxacillin-resistant, mecA-positive Staphylococcus spp. from unpasteurized milk. J. Food Prot. 2008, 71, 186–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resch, M.; Nagel, V.; Hertel, C. Antibiotic resistance of coagulase-negative staphylococci associated with food and used in starter cultures. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2008, 127, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanoukon, C.; Argemi, X.; Sogbo, F.; Orekan, J.; Keller, D.; Affolabi, D.; Schramm, F.; Riegel, P.; Baba-Moussa, L.; Prévost, G. Pathogenic features of clinically significant coagulase-negative staphylococci in hospital and community infections in Benin. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2017, 307, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, K.; Both, A.; Weibelberg, S.; Heilmann, C.; Rohde, H. Emergence of coagulase-negative staphylococci. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2020, 18, 349–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, V.C.; Romero, L.C.; Pinheiro-Hubinger, L.; Oliveira, A.; Martins, K.B.; da Cunha, M.L.R.S. Coagulase-negative staphylococci: A 20-year study on the antimicrobial resistance profile of blood culture isolates from a teaching hospital. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 24, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sender, G.; Pawlik, A.; Korwin-Kossakowska, A. Current concepts on the impact of coagulase-negative staphylococci causing bovine mastitis as a threat to human and animal health: A review. Anim. Sci. Pap. Rep. 2017, 35, 123–135. Available online: https://www.igbzpan.pl/uploaded/FSiBundleContentBlockBundleEntityTranslatableBlockTranslatableFilesElement/filePath/821/str123-136.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Kadariya, J.; Smith, T.C.; Thapaliya, D. Staphylococcus aureus and staphylococcal food-borne disease: An ongoing challenge in public health. Biomed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 827965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhusoodanan, J.; Seo, K.S.; Remortel, B.; Park, J.Y.; Hwang, S.Y.; Fox, L.K.; Park, Y.H.; Deobald, C.F.; Wang, D.; Liu, S.; et al. An enterotoxin-bearing pathogenicity island in Staphylococcus epidermidis. J. Bacteriol. 2011, 193, 1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitter, M.; Nerz, C.; Rosenstein, R.; Götz, F.; Hertel, C. DNA microarray-based detection of genes involved in safety and technologically relevant properties of food-associated coagulase-negative staphylococci. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2011, 145, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lina, G.; Bohach, G.A.; Nair, S.P.; Hiramatsu, K.; Jouvin-Marche, E.; Mariuzza, R. Standard nomenclature for the superantigens expressed by Staphylococcus. J. Infect. Dis. 2004, 189, 2334–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieza, M.Y.R.; Bonsaglia, E.C.R.; Rall, V.L.M.; Santos, M.V.; Silva, N.C.C. Staphylococcal enterotoxins: Description and importance in food. Pathogens 2024, 13, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etter, D.; Schelin, J.; Schuppler, M.; Johler, S. Staphylococcal Enterotoxin C—An update on SEC variants, their structure and properties, and their role in foodborne intoxications. Toxins 2020, 12, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández, M.M.; Cho, S.; De Marzi, M.C.; Kerzic, M.C.; Robinson, H.; Mariuzza, R.A. Crystal structure of staphylococcal enterotoxin I (SEI) in complex with HLA-DR1. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 29766–29775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, S.C.; Triplett, O.A.; Yu, L.-R.; Tolleson, W.H. Microcalorimetric investigations of reversible thermal unfolding of staphylococcal enterotoxins SEA, SEB and SEH. Toxins 2022, 14, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaiotta, G.; Ercolini, D.; Pennacchia, C.; Fusco, V.; Casaburi, A.; Pepe, O.; Villani, F. PCR detection of staphylococcal enterotoxin genes in Staphylococcus spp. strains isolated from meat and dairy products: Evidence for new variants of seG and seI in S. aureus AB-8802. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2004, 97, 719–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, R.S.C.; de Souza, C.P.; Pereira, K.S.; Del Aguila, E.M.; Paschoalin, V.M.F. Identification and molecular phylogeny of coagulase-negative staphylococci isolates from Minas Frescal cheese in southeastern Brazil: Superantigenic toxin production and antibiotic resistance. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 2641–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, A.P.C.; Borges, M.F.; de Figueiredo, E.A.T.; Arcuri, E.F. Diversity of Staphylococcus coagulase-positive and negative strains of coalho cheese and detection of enterotoxin encoding genes. Bol. Cent. Pesqui. Process. Aliment. 2018, 36, e57553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chajęcka-Wierzchowska, W.; Gajewska, J.; Wiśniewski, P.; Zadernowska, A. Enterotoxigenic potential of coagulase-negative staphylococci from ready-to-eat food. Pathogens 2020, 9, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Eiff, C.; Peters, G.; Heilmann, C. Pathogenesis of infections due to coagulase-negative staphylococci. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2002, 2, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, K.; Heilmann, C.; Peters, G. Coagulase-negative staphylococci. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2014, 27, 870–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Eiff, C.; Jansen, B.; Kohnen, W.; Becker, K. Infections associated with medical devices: Pathogenesis, management and prophylaxis. Drugs 2005, 65, 179–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, M.; Yamashita, A.; Hirakawa, H.; Kumano, M.; Morikawa, K.; Higashide, M.; Maruyama, A.; Inose, Y.; Matoba, K.; Toh, H.; et al. Whole genome sequence of Staphylococcus saprophyticus reveals the pathogenesis of uncomplicated urinary tract infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 13272–13277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammes, W.P.; Hertel, C. New developments in meat starter cultures. Meat Sci. 1998, 49 (Suppl. S1), S125–S138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrière, C.; Centeno, D.; Lebert, A.; Leroy-Sétrin, S.; Berdagué, J.L.; Talon, R. Roles of superoxide dismutase and catalase of Staphylococcus xylosus in the inhibition of linoleic acid oxidation. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2001, 201, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, D.W.; Lee, B.; Her, J.Y.; Lee, K.G.; Lee, J.H. Safety and technological characterization of coagulase-negative staphylococci isolates from traditional Korean fermented soybean foods for starter development. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016, 236, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Götz, F. Staphylococcus carnosus: A new host organism for gene cloning and protein production. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1990, 69 (Suppl. S19), 49S–53S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstein, R.; Nerz, C.; Biswas, L.; Resch, A.; Raddatz, G.; Schuster, S.C.; Götz, F. Genome analysis of the meat starter culture bacterium Staphylococcus carnosus TM300. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 811–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstein, R.; Götz, F. Genomic differences between the food-grade Staphylococcus carnosus and pathogenic staphylococcal species. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2010, 300, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnio, M.C.; Stachelhaus, T.; Francis, K.P.; Scherer, S. Pyridinyl polythiazole class peptide antibiotic micrococcin P1, secreted by foodborne Staphylococcus equorum WS2733, is biosynthesized nonribosomally. Eur. J. Biochem. 2001, 268, 6390–6401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deetae, P.; Bonnarme, P.; Spinnler, H.E.; Helinck, S. Production of volatile aroma compounds by bacterial strains isolated from different surface-ripened French cheeses. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 76, 1161–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravyts, F.; Steen, L.; Goemaere, O.; Paelinck, H.; De Vuyst, L.; Leroy, F. The application of staphylococci with flavour-generating potential is affected by acidification in fermented dry sausages. Food Microbiol. 2010, 27, 945–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, M.; Toldrá, F. Microbial enzymatic activities for improved fermented meats. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 22, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Heo, S.; Jeong, D.W. Genomic insights into Staphylococcus equorum KS1039 as a potential starter culture for the fermentation of high-salt foods. BMC Genom. 2018, 19, 4532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irlinger, F.; Loux, V.; Bento, P.; Gibrat, J.F.; Straub, C.; Bonnarme, P.; Landaud, S.; Monnet, C. Genome sequence of Staphylococcus equorum subsp. equorum Mu2, isolated from a French smear-ripened cheese. J. Bacteriol. 2012, 194, 5141–5142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, D.W.; Lee, J.H. Complete genome sequence of Staphylococcus succinus 14BME20 isolated from a traditional Korean fermented soybean food. Genome Announc. 2017, 5, e01731-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, A.M.S.; Mamizuka, E.M.; McCulloch, J.A. Staphylococcus aureus. In Microbiologia, 7th ed.; Alterthum, F., Ed.; Atheneu: São Paulo, Brazil, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Donlan, R.M. Biofilm formation: A clinically relevant microbiological process. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2001, 33, 1387–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, P.; Lemos, M.; Mergulhão, F.; Melo, L.; Simões, M. Antimicrobial resistance to disinfectants in biofilms. In Science Against Microbial Pathogens: Communicating Current Research and Technological Advances; Formatex: Badajoz, Spain, 2011; pp. 826–834. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10216/95596 (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Fontes, C.O.; Silva, V.L.; de Paiva, M.R.B.; Garcia, R.A.; Resende, J.A.; Ferreira-Machado, A.B.; Diniz, C.G. Prevalence, antimicrobial resistance, and virulence characteristics of mecA-encoding coagulase-negative staphylococci isolated from soft cheese in Brazil. J. Food Sci. 2013, 78, M1–M8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedriczewski, A.B.; Gandra, E.Á.; da Conceição, R.D.C.D.S.; Cereser, N.D.; Moreira, L.M.; Timm, C.D. Biofilm formation by coagulase-positive Staphylococcus aureus isolated from mozzarella cheese elaborated with buffalo milk and its effect on sensitivity to sanitizers. Acta Sci. Vet. 2018, 46, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, M.A.M.; da Silva, G.C.; Lopes, U.; Rosa, J.N.; Bazzolli, D.M.S.; Pimentel-Filho, N.J. Characterisation of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from artisanal unripened cheeses produced in São Paulo State, Brazil. Int. Dairy J. 2024, 149, 105825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda, A.P.A.; Chacón, R.D.; Costa, T.G.; Campos, G.Z.; Munive Nuñez, K.V.; Ramos, R.C.Z.; Camargo, C.H.; Lacorte, G.A.; Silva, N.C.C.; Pinto, U.M. Molecular characterization and virulence potential of Staphylococcus aureus from raw milk artisanal cheeses. Int. Dairy J. 2025, 160, 106097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, L.G.; Alvim, M.M.A.; Fabri, R.L.; Apolônio, A.C.M. Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation in Minas Frescal cheese packaging. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2021, 74, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajewska, J.; Chajęcka-Wierzchowska, W. Biofilm formation ability and presence of adhesion genes among coagulase-negative and coagulase-positive staphylococci isolates from raw cow’s milk. Pathogens 2020, 9, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, C.; Tremblay, Y.D.N.; Lamarche, D.; Blondeau, A.; Gaudreau, A.M.; Labrie, J.; Malouin, F.; Jacques, M. Coagulase-negative staphylococci species affect biofilm formation of other coagulase-negative and coagulase-positive staphylococci. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 6454–6464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Q.; Tang, X.; Dong, W.; Sun, N.; Yuan, W. A review of biofilm formation of Staphylococcus aureus and its regulation mechanism. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Wang, H.; Xiong, J.; Yang, G.X.; Hu, J.F.; Zhu, Q.; Chen, Z. Staphylococcus aureus biofilm: Formulation, regulatory, and emerging natural products-derived therapeutics. Biofilm 2024, 7, 100175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilcher, K.; Horswill, A.R. Staphylococcal biofilm development: Structure, regulation, and treatment strategies. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2020, 84, e00026-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.S.; Jiang, T.; Zhang, D.W.; Wang, H.Y.; Fang, T.; Li, C.C. Attachment characteristics and kinetics of biofilm formation by Staphylococcus aureus on ready-to-eat cooked beef contact surfaces. J. Food Sci. 2023, 88, 2595–2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolz, C.; Goerke, C.; Landmann, R.; Zimmerli, W.; Fluckiger, U. Transcription of clumping factor A in attached and unattached Staphylococcus aureus in vitro and during device-related infection. Infect. Immun. 2002, 70, 2758–2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabat, A.; Melles, D.C.; Martirosian, G.; Grundmann, H.; Van Belkum, A.; Hryniewicz, W. Distribution of the serine-aspartate repeat protein-encoding sdr genes among nasal-carriage and invasive Staphylococcus aureus strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2006, 44, 1135–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, E.; Pozzi, C.; Houston, P.; Humphreys, H.; Robinson, D.A.; Loughman, A.; Foster, T.J.; O’Gara, J.P. A novel Staphylococcus aureus biofilm phenotype mediated by the fibronectin-binding proteins, FnBPA and FnBPB. J. Bacteriol. 2008, 190, 3835–3850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maikranz, E.; Spengler, C.; Thewes, N.; Thewes, A.; Nolle, F.; Jung, P.; Bischoff, M.; Santen, L.; Jacobs, K. Different binding mechanisms of Staphylococcus aureus to hydrophobic and hydrophilic surfaces. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 19267–19275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burel, C.; Dreyfus, R.; Purevdorj-Gage, L. Physical mechanisms driving the reversible aggregation of Staphylococcus aureus and response to antimicrobials. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 94457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedarat, Z.; Taylor-Robinson, A.W. Biofilm formation by pathogenic bacteria: Applying a Staphylococcus aureus model to appraise potential targets for therapeutic intervention. Pathogens 2022, 11, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, K.; Jularic, M.; Horsburgh, S.M.; Hirschhausen, N.; Neumann, C.; Bertling, A.; Schulte, A.; Foster, S.; Kehrel, B.E.; Peters, G.; et al. Molecular characterization of a novel Staphylococcus aureus surface protein (SasC) involved in cell aggregation and biofilm accumulation. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e7567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banner, M.A.; Cunniffe, J.G.; Macintosh, R.L.; Foster, T.J.; Rohde, H.; Mack, D.; Hoyes, E.; Derrick, J.; Upton, M.; Handley, P.S. Localized tufts of fibrils on Staphylococcus epidermidis NCTC 11047 are comprised of the accumulation-associated protein. J. Bacteriol. 2007, 189, 2793–2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrigan, R.M.; Rigby, D.; Handley, P.; Foster, T.J. The role of Staphylococcus aureus surface protein SasG in adherence and biofilm formation. Microbiology 2007, 153, 2435–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohde, H.; Burdelski, C.; Bartscht, K.; Hussain, M.; Buck, F.; Horstkotte, M.A.; Knobloch, J.K.M.; Heilmann, C.; Herrmann, M.; Mack, D. Induction of Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilm formation via proteolytic processing of the accumulation-associated protein by staphylococcal and host proteases. Mol. Microbiol. 2005, 55, 1883–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, K.C.; Villa, B.; Paim, T.G.S.; Sambrano, G.E.; Oliveira, C.F.; D’Azevedo, P.A. Enhancement of antistaphylococcal activities of six antimicrobials against sasG-negative methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus: An in vitro biofilm model. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2012, 74, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savolainen, K.; Paulin, L.; Westerlund-Wikström, B.; Foster, T.J.; Korhonen, T.K.; Kuusela, P. Expression of pls, a gene closely associated with the mecA gene of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, prevents bacterial adhesion in vitro. Infect. Immun. 2001, 69, 3013–3020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juuti, K.M.; Sinha, B.; Werbick, C.; Peters, G.; Kuusela, P.I. Reduced adherence and host cell invasion by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus expressing the surface protein Pls. J. Infect. Dis. 2004, 189, 1574–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; Schäfer, D.; Juuti, K.M.; Peters, G.; Haslinger-Löffler, B.; Kuusela, P.I.; Sinha, B. Expression of Pls (plasmin sensitive) in Staphylococcus aureus negative for pls reduces adherence and cellular invasion and acts by steric hindrance. J. Infect. Dis. 2009, 200, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Artini, M.; Cellini, A.; Papa, R.; Tilotta, M.; Scoarughi, G.L.; Gazzola, S.; Fontana, C.; Tempera, G.; Cocconcelli, P.S.; Selan, L. Adhesive behaviour and virulence of coagulase negative staphylococci isolated from Italian cheeses. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2015, 28, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilmann, C.; Hartleib, J.; Hussain, M.S.; Peters, G. The multifunctional Staphylococcus aureus autolysin Aaa mediates adherence to immobilized fibrinogen and fibronectin. Infect. Immun. 2005, 73, 4793–4802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilmann, C.; Thumm, G.; Chhatwal, G.S.; Hartleib, J.; Uekötter, A.; Peters, G. Identification and characterization of a novel autolysin (Aae) with adhesive properties from Staphylococcus epidermidis. Microbiology 2003, 149, 2769–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoll, S.; Schlag, M.; Shkumatov, A.V.; Rautenberg, M.; Svergun, D.I.; Götz, F.; Stehle, T. Ligand-binding properties and conformational dynamics of autolysin repeat domains in staphylococcal cell wall recognition. J. Bacteriol. 2012, 194, 3789–3802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moormeier, D.E.; Bayles, K.W. Staphylococcus aureus biofilm: A complex developmental organism. Mol. Microbiol. 2017, 104, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangwani, N.; Kumari, S.; Das, S. Bacterial biofilms and quorum sensing: Fidelity in bioremediation technology. Biotechnol. Genet. Eng. Rev. 2016, 32, 43–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otto, M. Staphylococcal biofilms. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2008, 322, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman-Bausier, P.; El-Kirat-Chatel, S.; Foster, T.J.; Geoghegan, J.A.; Dufrêne, Y.F. Staphylococcus aureus fibronectin-binding protein A mediates cell-cell adhesion through low-affinity homophilic bonds. mBio 2015, 6, e00413-15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, H.T.T.; Nguyen, T.H.; Otto, M. The staphylococcal exopolysaccharide PIA—Biosynthesis and role in biofilm formation, colonization, and infection. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mack, D.; Fischer, W.; Krokotsch, A.; Leopold, K.; Hartmann, R.; Egge, H.; Laufs, R. The intercellular adhesin involved in biofilm accumulation of Staphylococcus epidermidis is a linear β-1,6-linked glucosaminoglycan: Purification and structural analysis. J. Bacteriol. 1996, 178, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramton, S.E.; Gerke, C.; Schnell, N.F.; Nichols, W.W.; Götz, F. The intercellular adhesion (ica) locus is present in Staphylococcus aureus and is required for biofilm formation. Infect. Immun. 1999, 67, 5427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramton, S.E.; Ulrich, M.; Götz, F.; Döring, G. Anaerobic conditions induce expression of polysaccharide intercellular adhesin in Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis. Infect. Immun. 2001, 69, 4079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cucarella, C.; Solano, C.; Valle, J.; Amorena, B.; Lasa, Í.; Penadés, J.R. Bap, a Staphylococcus aureus surface protein involved in biofilm formation. J. Bacteriol. 2001, 183, 2888–2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, C.R.; Woods, K.M.; Longo, G.M.; Kiedrowski, M.R.; Paharik, A.E.; Büttner, H.; Christner, M.; Boissy, R.J.; Horswill, A.R.; Rohde, H.; et al. Accumulation-associated protein enhances Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilm formation under dynamic conditions and is required for infection in a rat catheter model. Infect. Immun. 2015, 83, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohde, H.; Burandt, E.C.; Siemssen, N.; Frommelt, L.; Burdelski, C.; Wurster, S.; Scherpe, S.; Davies, A.P.; Harris, L.G.; Horstkotte, M.A.; et al. Polysaccharide intercellular adhesin or protein factors in biofilm accumulation of Staphylococcus epidermidis and Staphylococcus aureus isolated from prosthetic hip and knee joint infections. Biomaterials 2007, 28, 1711–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.R.; Fouts, D.E.; Archer, G.L.; Mongodin, E.F.; DeBoy, R.T.; Ravel, J.; Paulsen, I.T.; Kolonay, J.F.; Brinkac, L.; Beanan, M.; et al. Insights on evolution of virulence and resistance from the complete genome analysis of an early methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain and a biofilm-producing methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis strain. J. Bacteriol. 2005, 187, 2426–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cue, D.; Lei, M.G.; Lee, C.Y. Genetic regulation of the intercellular adhesion locus in Staphylococci. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2012, 2, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Gal, G.; Kahila-Blum, S.E.; Hadas, L.; Ehricht, R.; Monecke, S.; Leitner, G. Host-specificity of Staphylococcus aureus causing intramammary infections in dairy animals assessed by genotyping and virulence genes. Vet. Microbiol. 2015, 176, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasamiravaka, T.; Labtani, Q.; Duez, P.; El Jaziri, M. The formation of biofilms by Pseudomonas aeruginosa: A review of the natural and synthetic compounds interfering with control mechanisms. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 759348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, G.; Kaplan, H.B.; Kolter, R. Biofilm formation as microbial development. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2000, 54, 49–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Sarkar, S.; Das, B.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Tribedi, P. Biofilm, pathogenesis and prevention—A journey to break the wall: A review. Arch. Microbiol. 2016, 198, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costerton, J.W. Introduction to biofilm. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 1999, 11, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lister, J.L.; Horswill, A.R. Staphylococcus aureus biofilms: Recent developments in biofilm dispersal. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2014, 4, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boles, B.R.; Horswill, A.R. Staphylococcal biofilm disassembly. Trends Microbiol. 2011, 19, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandana, D.S. Genetic regulation, biosynthesis and applications of extracellular polysaccharides of the biofilm matrix of bacteria. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 291, 119536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Periasamy, S.; Joo, H.S.; Duong, A.C.; Bach, T.H.L.; Tan, V.Y.; Chatterjee, S.S.; Cheung, G.Y.C.; Otto, M. How Staphylococcus aureus biofilms develop their characteristic structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 1281–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G.Y.; Joo, H.S.; Chatterjee, S.S.; Otto, M. Phenol-soluble modulins—Critical determinants of staphylococcal virulence. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2014, 38, 698–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, K.; Syed, A.K.; Stephenson, R.E.; Rickard, A.H.; Boles, B.R. Functional amyloids composed of phenol soluble modulins stabilize Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinelli, P.; Pallares, I.; Navarro, S.; Ventura, S. Dissecting the contribution of Staphylococcus aureus α-phenol-soluble modulins to biofilm amyloid structure. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 34552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabst, B.; Pitts, B.; Lauchnor, E.; Stewart, P.S. Gel-entrapped Staphylococcus aureus bacteria as models of biofilm infection exhibit growth in dense aggregates, oxygen limitation, antibiotic tolerance, and heterogeneous gene expression. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 6294–6301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flemming, H.C.; Wingender, J.; Szewzyk, U.; Steinberg, P.; Rice, S.A.; Kjelleberg, S. Biofilms: An emergent form of bacterial life. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciofu, O.; Moser, C.; Jensen, P.Ø.; Høiby, N. Tolerance and resistance of microbial biofilms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 20, 621–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Tong, Y.; Cheng, J.; Abbas, Z.; Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Si, D.; Zhang, R. Biofilm and small colony variants—An update on Staphylococcus aureus strategies toward drug resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conlon, B.P.; Rowe, S.E.; Gandt, A.B.; Nuxoll, A.S.; Donegan, N.P.; Zalis, E.A.; Clair, G.; Adkins, J.N.; Cheung, A.L.; Lewis, K. Persister formation in Staphylococcus aureus is associated with ATP depletion. Nat. Microbiol. 2016, 1, 16051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, J.W.; Waigh, T.A.; Lu, J.R.; Roberts, I.S. Microrheology and spatial heterogeneity of Staphylococcus aureus biofilms modulated by hydrodynamic shear and biofilm-degrading enzymes. Langmuir 2019, 35, 3553–3561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, E.S.; Weiss, A.; Migas, L.G.; Freiberg, J.A.; Djambazova, K.V.; Neumann, E.K.; Van de Plas, R.; Spraggins, J.M.; Skaar, E.P.; Caprioli, R.M. Imaging mass spectrometry reveals complex lipid distributions across Staphylococcus aureus biofilm layers. J. Mass Spectrom. Adv. Clin. Lab 2022, 26, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- França, A.; Gaio, V.; Lopes, N.; Melo, L.D.R. Virulence factors in coagulase-negative staphylococci. Pathogens 2021, 10, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharyya, D.; Banerjee, J.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Mondal, B.; Nanda, P.K.; Samanta, I.; Mahanti, A.; Das, A.K.; Das, G.; Dandapat, P.; et al. First report on vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in bovine and caprine milk. Microb. Drug Resist. 2016, 22, 675–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, L.Z.; Dutra, M.C.; Moreno, M.; Ferreira, T.S.; Silva, G.F.; Matajira, C.E.; Silva, A.P.; Moreno, A.M. Vancomycin-intermediate livestock-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus ST398/t9538 from swine in Brazil. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2016, 111, 659–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastião Rocha, P.A.; Monteiro Marques, J.M.; Barreto, A.; Semedo-Lemsaddek, T. Enterococcus spp. from Azeitão and Nisa PDO-cheeses: Surveillance for antimicrobial drug resistance. LWT 2022, 154, 112622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darby, E.M.; Trampari, E.; Siasat, P.; Gaya, M.S.; Alav, I.; Webber, M.A.; Blair, J.M.A. Molecular mechanisms of antibiotic resistance revisited. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 280–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Ahn, J. Emergence and spread of antibiotic-resistant foodborne pathogens from farm to table. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2022, 31, 1481–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Huang, Z.; Malakar, P.K.; Pan, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Z. Antimicrobial resistomes in food chain microbiomes. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 64, 6953–6974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, C.R.S.; Salamandane, A.; Vieira, E.J.F.; Salamandane, C. Antibiotic resistance in fermented foods chain: Evaluating the risks of emergence of Enterococci as an emerging pathogen in raw milk cheese. Int. J. Microbiol. 2024, 2024, 2409270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Cheng, F.; Wei, X.; Bai, Y.; Wang, Q.; Li, B.; Zhou, Y.; Zhai, B.; Zhou, X.; Wang, W.; et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA): Resistance, prevalence, and coping strategies. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlynarczyk, A.; Mlynarczyk, B.; Kmera-Muszynska, M.; Majewski, S.; Mlynarczyk, G. Mechanisms of the resistance and tolerance to beta-lactam and glycopeptide antibiotics in pathogenic gram-positive cocci. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2009, 9, 1527–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tulinski, P.; Fluit, A.C.; Wagenaar, J.A.; Mevius, D.; van de Vijver, L.; Duim, B. Methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococci on pig farms as a reservoir of heterogeneous staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec elements. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brdová, D.; Ruml, T.; Viktorová, J. Mechanism of staphylococcal resistance to clinically relevant antibiotics. Drug Resist. Updat. 2024, 77, 101147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miragaia, M. Factors contributing to the evolution of mecA-mediated β-lactam resistance in staphylococci: Update and new insights from whole genome sequencing (WGS). Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appelbaum, P.C.; Bozdogan, B. Vancomycin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Clin. Lab. Med. 2004, 24, 381–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlynarczyk-Bonikowska, B.; Kowalewski, C.; Krolak-Ulinska, A.; Marusza, W. Molecular mechanisms of drug resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehm, S.J.; Tice, A. Staphylococcus aureus: Methicillin-susceptible S. aureus to methicillin-resistant S. aureus and vancomycin-resistant S. aureus. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010, 51 (Suppl. S2), S176–S182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, B.; Singh, A.K.; Ghosh, A.; Bal, M. Identification and characterization of a vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from Kolkata (South Asia). J. Med. Microbiol. 2008, 57 Pt 1, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Clark, N.C.; McDougal, L.K.; Hageman, J.; McDonald, L.C.; Patel, J.B. Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates associated with Inc18-like vanA plasmids in Michigan. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008, 52, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limbago, B.M.; Kallen, A.J.; Zhu, W.; Eggers, P.; McDougal, L.K.; Albrecht, V.S. Report of the 13th vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolate from the United States. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014, 52, 998–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGuinness, W.A.; Malachowa, N.; DeLeo, F.R. Vancomycin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2017, 90, 269–281. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, D.R.; Howden, B.P.; Peleg, A.Y. The interface between antibiotic resistance and virulence in Staphylococcus aureus and its impact upon clinical outcomes. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 53, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkuraythi, D.M.; Alkhulaifi, M.M.; Binjomah, A.Z.; Alarwi, M.; Mujallad, M.I.; Alharbi, S.A.; Alshomrani, M.; Gojobori, T.; Alajel, S.M. Comparative genomic analysis of antibiotic resistance and virulence genes in Staphylococcus aureus isolates from patients and retail meat. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1339339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariati, A.; Dadashi, M.; Chegini, Z.; van Belkum, A.; Mirzaii, M.; Khoramrooz, S.S.; Darban-Sarokhalil, D. The global prevalence of daptomycin, tigecycline, quinupristin/dalfopristin, and linezolid-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase-negative staphylococci strains: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2020, 9, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malachowa, N.; DeLeo, F.R. Mobile genetic elements of Staphylococcus aureus. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2010, 67, 3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podkowik, M.; Bystroń, J.; Bania, J. Genotypes, antibiotic resistance, and virulence factors of staphylococci from ready-to-eat food. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2012, 9, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klempt, M.; Franz, C.M.A.P.; Hammer, P. Characterization of coagulase-negative staphylococci and macrococci isolated from cheese in Germany. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 7951–7958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajewska, J.; Chajęcka-Wierzchowska, W.; Zadernowska, A. Occurrence and Characteristics of Staphylococcus aureus strains along the production chain of raw milk cheeses in Poland. Molecules 2022, 27, 6569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allaion, J.R.; Barrionuevo, K.G.; Grande Burgos, M.J.; Gálvez, A.; Franco, B.D.G.M. Staphylococcus aureus from Minas artisanal cheeses: Biocide tolerance, antibiotic resistance and enterotoxin genes. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, R.A.C.; Ferreira, F.A.; Rubio Cieza, M.Y.; Silva, N.C.C.; Miotto, M.; Carvalho, M.M.; Bazzo, B.R.; Botelho, L.A.B.; Dias, R.S.; De Dea Lindner, J. Staphylococcus aureus isolated from traditional artisanal raw milk cheese from Southern Brazil: Diversity, virulence, and antimicrobial resistance profile. J. Food Prot. 2024, 87, 100285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resende, J.A.; Fontes, C.O.; Ferreira-Machado, A.B.; Nascimento, T.C.; Silva, V.L.; Diniz, C.G. Antimicrobial-resistance genetic markers in potentially pathogenic Gram-positive cocci isolated from Brazilian soft cheese. J. Food Sci. 2018, 83, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, E.M.; Jiang, Y.; Tinoco, M.B. Staphylococcus aureus—Dairy. In Encyclopedia of Dairy Sciences, 3rd ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 123–135. [Google Scholar]

- Jenul, C.; Horswill, A.R. Regulation of Staphylococcus aureus virulence. Microbiol. Spectr. 2019, 7, GPP3-0031-2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D. Enterotoxin-producing Staphylococcus aureus. In Molecular Medical Microbiology, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 1234–1245. [Google Scholar]

- Alibayov, B.; Baba-Moussa, L.; Sina, H.; Zdeňková, K.; Demnerová, K. Staphylococcus aureus mobile genetic elements. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2014, 41, 5005–5018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaban, N.; Rasooly, A. Staphylococcal enterotoxins. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2000, 61, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Sánchez, S.; Ramos, I.M.; Rodríguez-Pérez, M.; Poveda, J.M.; Seseña, S.; Palop, M.L. Lactic acid bacteria as biocontrol agents to reduce Staphylococcus aureus growth, enterotoxin production and virulence gene expression. LWT 2022, 170, 114025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, E.L.; Otto, M.; Cheung, G.Y.C. Basis of virulence in enterotoxin-mediated staphylococcal food poisoning. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derzelle, S.; Dilasser, F.; Duquenne, M.; Deperrois, V. Differential temporal expression of the staphylococcal enterotoxins genes during cell growth. Food Microbiol. 2009, 26, 896–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeaki, N.; Johler, S.; Skandamis, P.N.; Schelin, J. The role of regulatory mechanisms and environmental parameters in staphylococcal food poisoning and resulting challenges to risk assessment. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, D.; Harper, L.; Shopsin, B.; Torres, V.J. Staphylococcus aureus pathogenesis in diverse host environments. Pathog. Dis. 2017, 75, ftx005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.S.; Wigneshweraraj, S. Regulation of virulence gene expression. Virulence 2014, 5, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, M.E.; Nygaard, T.K.; Ackermann, L.; Watkins, R.L.; Zurek, O.W.; Pallister, K.B.; Griffith, S.; Kiedrowski, M.R.; Flack, C.E.; Kavanaugh, J.S.; et al. Staphylococcus aureus nuclease is an SaeRS-dependent virulence factor. Infect. Immun. 2013, 81, 1316–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulrich, M.; Bastian, M.; Cramton, S.E.; Ziegler, K.; Pragman, A.A.; Bragonzi, A.; Memmi, G.; Wolz, C.; Schlievert, P.M.; Cheung, A.; et al. The staphylococcal respiratory response regulator SrrAB induces ica gene transcription and polysaccharide intercellular adhesin expression, protecting Staphylococcus aureus from neutrophil killing under anaerobic growth conditions. Mol. Microbiol. 2007, 65, 1276–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.N.; Crosby, H.A.; Spaulding, A.R.; Salgado-Pabón, W.; Malone, C.L.; Rosenthal, C.B.; Schlievert, P.M.; Boyd, J.M.; Horswill, A.R. The Staphylococcus aureus ArlRS two-component system is a novel regulator of agglutination and pathogenesis. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauserman, M.R.; Sullivan, L.E.; James, K.L.; Ferraro, M.J.; Rice, K.C. Response of Staphylococcus aureus physiology and Agr quorum sensing to low-shear modeled microgravity. J. Bacteriol. 2024, 206, e00272-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, M.A.; Lilo, S.; Nygaard, T.; Voyich, J.M.; Torres, V.J. Rot and SaeRS cooperate to activate expression of the staphylococcal superantigen-like exoproteins. J. Bacteriol. 2012, 194, 4355–4365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choueiry, F.; Xu, R.; Zhu, J. Adaptive metabolism of Staphylococcus aureus revealed by untargeted metabolomics. J. Proteome Res. 2022, 21, 470–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howden, B.P.; Giulieri, S.G.; Lung, T.W.F.; Baines, S.L.; Sharkey, L.K.; Lee, J.Y.H.; Hachani, A.; Monk, I.R.; Stinear, T.P. Staphylococcus aureus host interactions and adaptation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, V.M.; Dias, R.S.; Soares, B.M.; Clementino, L.A.; Araújo, C.P.; Rosa, C.A. The influence of ripening period length and season on the microbiological parameters of a traditional Brazilian cheese. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2013, 44, 743–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rola, J.G.; Czubkowska, A.; Korpysa-Dzirba, W.; Osek, J. Occurrence of Staphylococcus on farms with small-scale production of raw milk cheeses in Poland. Toxins 2016, 8, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minutillo, R.; Pirard, B.; Fatihi, A.; Cavaiuolo, M.; Lefebvre, D.; Gérard, A.; Taminiau, B.; Nia, Y.; Hennekinne, J.-A.; Daube, G.; et al. The enterotoxin gene profiles and enterotoxin production of Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from artisanal cheeses in Belgium. Foods 2023, 12, 4019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastos, C.P.; Bassani, M.T.; Mata, M.M.; Lopes, G.V.; da Silva, W.P. Prevalence and expression of staphylococcal enterotoxin genes in Staphylococcus aureus isolated from food poisoning outbreaks. Can. J. Microbiol. 2017, 63, 834–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johler, S.; Giannini, P.; Jermini, M.; Hummerjohann, J.; Baumgartner, A.; Stephan, R. Further evidence for staphylococcal food poisoning outbreaks caused by egc-encoded enterotoxins. Toxins 2015, 7, 997–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fricker, C.R.; Tompkin, R.B. Staphylococcus aureus. In Compendium of Methods for the Microbiological Examination of Foods, 4th ed.; Vanderzant, C., Splittstoesser, D.F., Eds.; APHA Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Argudín, M.Á.; Mendoza, M.C.; Rodicio, M.R. Food poisoning and Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxins. Toxins 2010, 2, 1751–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandrasekaran, S.; Jiang, D. A dose response model for Staphylococcus aureus. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 12279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, E.C.D. Foodborne and waterborne disease in Canada—1980 annual summary. J. Food Prot. 1987, 50, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bone, F.J.; Bogie, D.; Morgan-Jones, S.C. Staphylococcal food poisoning from sheep milk cheese. Epidemiol. Infect. 1989, 103, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kérouanton, A.; Hennekinne, J.A.; Letertre, C.; Petit, L.; Chesneau, O.; Brisabois, A.; De Buyser, M.L. Characterization of Staphylococcus aureus strains associated with food poisoning outbreaks in France. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2007, 115, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieneke, A.A.; Roberts, D.; Gilbert, R.J. Staphylococcal food poisoning in the United Kingdom, 1969–1990. Epidemiol. Infect. 1993, 110, 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabioni, J.G.; Hirooka, E.Y.; de Souza, M.L. Intoxicação alimentar por queijo Minas contaminado com Staphylococcus aureus. Rev. Saúde Pública 1988, 22, 458–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, M.L.; do Carmo, L.S.; dos Santos, E.J.; Pereira, J.L.; Bergdoll, M.S. Enterotoxin H in staphylococcal food poisoning. J. Food Prot. 1996, 59, 559–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- do Carmo, L.S.; Dias, R.S.; Linardi, V.R.; Sena, M.J.; Santos, D.A.; Faria, M.E.; Pena, E.C.; Jett, M.; Heneine, L.G. Food poisoning due to enterotoxigenic strains of Staphylococcus present in Minas cheese and raw milk in Brazil. Food Microbiol. 2002, 19, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostyn, A.; de Buyser, M.L.; Guillier, F.; Groult, J.; Félix, B.; Salah, S.; Delmas, G.; Hennekinne, J.A. First evidence of a food poisoning outbreak due to staphylococcal enterotoxin type E, France, 2009. Euro Surveill. 2010, 15, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardamone, C.; Castello, A.; Oliveri, G.; Costa, A.; Sciortino, S.; Nia, Y.; Hennekinne, J.-A.; Romano, A.; Zuccon, F.; Decastelli, L. Staphylococcal food poisoning outbreaks occurred in Sicily (Italy) from 2009 to 2016. Ital. J. Food Saf. 2024, 13, 11667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipello, V.; Bonometti, E.; Campagnani, M.; Bertoletti, I.; Romano, A.; Zuccon, F.; Campanella, C.; Losio, M.N.; Finazzi, G. Investigation and follow-up of a staphylococcal food poisoning outbreak linked to the consumption of traditional hand-crafted alm cheese. Pathogens 2020, 9, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, D.M.; Romano, A.; Tramuta, C.; Distasio, P.; Decastelli, L. A foodborne outbreak caused by staphylococcal enterotoxins in cheese sandwiches in northern Italy. Ital. J. Food Sci. 2024, 36, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde e Ambiente. In Surtos de Doenças de Transmissão Hídrica e Alimentar—Informe; Ministério da Saúde: Brasilia, Brazil, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA); European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). The European Union One Health 2022 Zoonoses Report. EFSA J. 2023, 21, e8442. [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai, Y.; Pires, S.M.; Kubota, K.; Asakura, H. Attributing human foodborne diseases to food sources and water in Japan using analysis of outbreak surveillance data. J. Food Prot. 2020, 83, 2087–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schelin, J.; Wallin-Carlquist, N.; Cohn, M.T.; Lindqvist, R.; Barker, G.C.; Rådström, P. The formation of Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxin in food environments and advances in risk assessment. Virulence 2011, 2, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emiliano, J.V.S.; Fusieger, A.; Camargo, A.C.; Rodrigues, F.F.C.; Nero, L.A.; Perrone, Í.T.; Carvalho, A.F. Staphylococcus aureus in dairy industry: Enterotoxin production, biofilm formation, and use of lactic acid bacteria for its biocontrol. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2024, 21, 601–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pineda, A.P.A.; Campos, G.Z.; Pimentel-Filho, N.J.; Franco, B.D.G.M.; Pinto, U.M. Brazilian artisanal cheeses: Diversity, microbiological safety, and challenges for the sector. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 666922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacorte, G.A.; Cruvinel, L.A.; Ávila, M.P.; Dias, M.F.; Pereira, A.A.; Nascimento, A.M.A.; Franco, B.D.G.M. Investigating the influence of food safety management systems (FSMS) on microbial diversity of Canastra cheeses and their processing environments. Food Microbiol. 2022, 105, 104023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finger, J.A.F.F.; Lima, E.M.F.; Coelho, K.S.; Behrens, J.H.; Landgraf, M.; Franco, B.D.G.M.; Pinto, U.M. Adherence to food hygiene and personal protection recommendations for prevention of COVID-19. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 112, 847–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Haddad, L.; Roy, J.P.; Khalil, G.E.; St-Gelais, D.; Champagne, C.P.; Labrie, S.; Moineau, S. Efficacy of two Staphylococcus aureus phage cocktails in cheese production. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016, 217, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touaitia, R.; Ibrahim, N.A.; Touati, A.; Idres, T. Staphylococcus aureus in bovine mastitis: A narrative review of prevalence, antimicrobial resistance, and advances in detection strategies. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayorga-Martinez, C.C.; Castoralova, M.; Zelenka, J.; Ruml, T.; Pumera, M. Swarming magnetic microrobots for pathogen isolation from milk. Small 2023, 19, e2205047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Dou, L.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, L.; Yang, H.; Wen, K.; Yu, X.; Shen, J.; Wang, Z. A comprehensive review on the detection of Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxins in food samples. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2024, 23, e13264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food Standards Australia New Zealand. Compendium of Microbiological Criteria for Food; First Published October 2016; Last Updated March 2022; Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ): Majura Park, Australia, 2022.

- Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, and Supply. Normative Instruction No. 161, of 1 July 2022. In Official Gazette of the Union; Section 1; Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, and Supply: Brasilia, Brazil, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada. Draft—Table of Microbiological Criteria for Food; Government of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2023.

- World Bank. Comparison of Microbiological Criteria in Food Products in the EU and China; The World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Guidance on Cheese as Raw Material in the Manufacture of Food Products; EDA/EUCOLAIT: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Compliance Policy Guide Sec. 527.300 Dairy Products—Microbial Contaminants and Alkaline Phosphatase Activity; U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA; EUA: Brussels, Belgium, 2010.

| Coagulase-Positive Staphylococci (CoPS) Species | ||

| Staphylococcus argenteus | Staphylococcus cornubiensis | Staphylococcus lutrae |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Staphylococcus delphini | Staphylococcus pseudintermedius |

| Staphylococcus coagulans | Staphylococcus intermedius | Staphylococcus schweitzeri |

| Coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS) species | ||

| Staphylococcus americanisciuri | Staphylococcus edaphicus | Staphylococcus pettenkoferi |

| Staphylococcus argensis | Staphylococcus epidermidis | Staphylococcus piscifermentans |

| Staphylococcus arlettae | Staphylococcus equorum | Staphylococcus pragensis |

| Staphylococcus auricularis | Staphylococcus felis | Staphylococcus pseudolugdunensis |

| Staphylococcus borealis | Staphylococcus gallinarum | Staphylococcus pseudoxylosus |

| Staphylococcus brunensis | Staphylococcus haemolyticus | Staphylococcus ratti |

| Staphylococcus caeli | Staphylococcus hominis | Staphylococcus rostri |

| Staphylococcus caledonicus | Staphylococcus hsinchuensis | Staphylococcus saccharolyticus |

| Staphylococcus canis | Staphylococcus kloosii | Staphylococcus saprophyticus |

| Staphylococcus capitis | Staphylococcus leei | Staphylococcus schleiferi |

| Staphylococcus caprae | Staphylococcus lloydii | Staphylococcus shinii |

| Staphylococcus carnosus | Staphylococcus lugdunensis | Staphylococcus simiae |

| Staphylococcus casei | Staphylococcus lyticans | Staphylococcus simulans |

| Staphylococcus chromogenes | Staphylococcus marylandisciuri | Staphylococcus succinus |

| Staphylococcus cohnii | Staphylococcus massiliensis | Staphylococcus taiwanensis |

| Staphylococcus condimenti | Staphylococcus microti | Staphylococcus ureilyticus |

| Staphylococcus croceilyticus | Staphylococcus muscae | Staphylococcus warneri |

| Staphylococcus debuckii | Staphylococcus nepalensis | Staphylococcus xylosus |

| Staphylococcus devriesei | Staphylococcus pasteuri | - |

| Staphylococcus durrellii | Staphylococcus petrasii | - |

| Coagulase-variable staphylococci (CoVS) species | ||

| Staphylococcus agnetis | Staphylococcus roterodami | - |

| Staphylococcus hyicus | Staphylococcus singaporensis | - |

| Name | Gene | Genetic Element | Size (kDa) | Crystal Structure Solved * | Stability | Superantigenic Activity | Emetic Activity | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcal enterotoxins (SEs) | ||||||||

| SEA | sea | Prophage | 27.1 | Yes | Heat- and protease- stable | Yes | Yes | Food poisoning, dairy products, human, bovine, caprine, ovine |

| SEB | seb | SaPI3, chromosome, plasmid | 28.4 | Yes | Heat-stable | Yes | Yes | Food poisoning, dairy products, human, bovine, caprine, ovine |

| SEC | sec | SaPI | 27.5–27.6 | Yes | Heat-stable | Yes | Yes | Food poisoning, dairy products, human, bovine, caprine, ovine |

| SEC-1 | sec | SaPI | 27.5–27.6 | Nd | Presumed heat-stable | Yes | Yes | Human |

| SEC-2 | sec | SaPI | 27.5–27.6 | Yes | Heat-stable | Yes | Nd | Human |

| SEC-3 | sec | SaPI | 27.5–27.6 | Yes | Heat-stable | Yes | Yes | Human |

| SED | sed | Plasmid | 26.9 | Yes | Heat-stable | Yes | Yes | Food poisoning, bovine |

| SEE | see | Prophage (hypothetical location) | 26.4 | No | Heat-stable | Yes | Yes | Food poisoning, unpasteurized milk soft cheese |

| SEG | seg | egc1, egc2, egc3, egc4 | 27.0 | Yes | Heat-stable | Yes | Yes | Bovine |

| SEH | seh | Transposon | 25.1 | Yes | Heat-stable | Yes | Yes | Empyema human |

| SEI | sei | egc1, egc2, egc3 | 24.9 | Yes | Heat-stable | Yes | Yes | Mastitis cows, humans |

| SEs-like (SEls) | ||||||||

| SElJ | selj | Plasmid | 28.5 | No | Nd | Yes | Nd | Epidemiologically implicated in food poisoning |

| SElK | selk | SaPI1, SaPI3, SaPI5, SaPIbov1, prophages | 26.0 | Yes | Nd | Yes | Nd | Human |

| SElL | sell | SaPIn1, SaPIm1, SaPImw2, SaPIbov1 | 26.0 | No | Nd | Yes | Yes | Human |

| SElM | selm | egc1, egc2 | 24.8 | No | Nd | Yes | Yes | Bovine |

| SElN | seln | egc1, egc2, egc3, egc4 | 26.1 | No | Nd | Yes | Yes | Human |

| SElO | selo | egc1, egc2, egc3, egc4, transposon | 26.7 | No | Nd | Yes | Yes | Human |

| SElP | selp | Prophage | 27.0 | No | Nd | Yes | Yes | Human, ulcer |

| SElQ | selq | SaPI1, SaPI3, SaPI5, prophage | 25.0 | No | Nd | Yes | Yes | Human |

| SElR | selr | Plasmid | 27.0 | No | Nd | Yes | Yes | Human |

| SElS | sels | Plasmid | 26.2 | No | Nd | Yes | Yes | Not found |

| SElT | selt | Plasmid | 22.6 | No | Nd | Yes | Yes | Not found |

| SElU | selu | egc2, egc3 | 27.1 | No | Nd | Yes | Nd | Human |

| SElV | selv | egc4 | Nd | No | Nd | Yes | Nd | Not found |

| SElW | selw | egc4 | Nd | No | Nd | Yes | Nd | Human |

| SElX | selx | Chromosome | Nd | No | Nd | Yes | Nd | Milk, raw meat, human |

| SElY | sely | Chromosome | Nd | No | Nd | Yes | Nd | Human |

| SElZ | selz | Chromosome | Nd | No | Nd | Nd | Nd | Bovine |

| Toxic shock syndrome toxin-1 (TSST-1) | ||||||||

| TSST-1 | tst/TssT | Chromosome | Nd | Nd | Heat- and protease-stable | Yes | No | Human |

| Main Target | Antibiotic Class | Resistance Gene | Encoded Protein |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell wall synthesis | Beta-lactam | mecA | Penicillin-binding protein 2a (PBP2a) |

| mecA1 | |||

| blaZ | Beta-lactamase | ||

| blaTEM | |||

| Glycopeptide | bleO | Bleomycin resistant proteins | |

| vanA | Vancomycin/teicoplanin A-type resistance protein | ||

| Phosphonic acid | fosB-saur | Metallothiol transferase | |

| Folic acid synthesis | Diaminopyrimidine | dfrG | Dihydrofolate reductase |

| Trimethoprim | dfrA12 | Dihydrofolate reductase | |

| dfr17 | |||

| Nucleic acid synthesis | Quinolone | gyrA | DNA gyrase subunit A |

| Nucleic acid and protein synthesis | Nucleoside | sat-4 | Streptothricin N-acetyltransferase and streptothricin |

| Protein synthesis | Aminoglycoside | aacA-aphD | 6′-aminoglycoside N-acetyltransferase/2″-aminoglycoside phosphotransferase |

| aadA2 | Spectinomycin 9-adenylyltransferase | ||

| aadA5 | Aminoglycoside-3′-adenylyltransferase | ||

| ant(4′)-Ia | Aminoglycoside adenyltransferase | ||

| aph(2″)-Ih | Aminoglycoside 2″-phosphotransferase | ||

| aph(3′)-IIIa | Aminoglycoside 3′-phosphotransferase | ||

| Fusidane | fusB | 2-domain zinc-binding protein | |

| fusC | |||

| Lincosamide | lnuA | Lincosamide nucleotidyltransferase | |

| Lincosamide/ macrolide/streptogramin | ermC | rRNA adenine N-6-methyltransferase | |

| Lincosamide/pleuromutilin/streptogramin/ | salA | Iron-sulfur cluster carrier protein | |

| vgaA-lc | ABC transporter | ||

| Macrolide | mphC | Macrolide 2′-phosphotransferase | |

| Macrolide/streptogramin | msrA | Peptide methionine sulfoxide reductase | |

| Phenicol | fexA | Chloramphenicol/florfenicol exporter | |

| cmlA1 | Bcr/CflA family efflux transporter | ||

| Tetracycline | tetK | Tetracycline resistance protein | |

| tetL | |||

| tet38 | Tetracycline efflux MFS transporter |

| Year | Location | Product | Enterotoxin Type | Symptoms | Number of Patients (Deaths) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | Canada | Curd cheese | SEA, SEC | Nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, and diarrhea | 62 (0) | [206] |

| 1981 | United Kingdom | Halloumi cheese | SEA | Nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, and diarrhea | 4 (0) | [207] |

| 1981 | France | Raw milk semi-hard cheese | SEA | Unknown | 4 (0) | [208] |

| 1983 | France | Raw milk semi-hard cheese | SEA, SED | Vomiting and abdominal cramps | 20 (0) | [208] |

| 1983 | France | Raw milk soft cheese | Absent | Vomiting and diarrhea | 4 (0) | [208] |

| 1985 | France | Soft cheese | SEB | Vomiting and diarrhea | 2 (0) | [208] |

| 1985 | France | Soft cheese | SEB | Vomiting and diarrhea | 3 (0) | [208] |

| 1985 | United Kingdom | Raw ewe’s milk cheese | SEA | Nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, and diarrhea | 27 (0) | [209] |

| 1986 | France | Sheep’s milk cheese | SEB | Unknown | Unknown | [208] |

| 1988 | Brazil | Fresh Minas cheese | SEA, SEB, SED, SEE | Nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, and diarrhea | 4 (0) | [210] |

| 1995 | Brazil | Minas cheese | SEH | Vomiting and diarrhea | 7 (0) | [211] |

| 1997 | France | Raw milk cheese | Present but not specified | Unknown | 43 (0) | [208] |

| 1998 | France | Raw milk cheese | Present but not specified | Vomiting, abdominal cramps, and diarrhea | 47 (0) | [208] |

| 1998 | France | Raw milk semi-hard cheese | Absent | Vomiting and abdominal cramps | 10 (0) | [208] |

| 1999 | Brazil | Minas cheese | SEA, SEB, SEC | Vomiting, dizziness, chills, headaches, and diarrhea | 378 (0) | [212] |

| 2000 | France | Raw sheep’s milk cheese | SEA | Unknown | Unknown | [208] |

| 2001 | France | Sliced soft cheese | SEA | Nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, and diarrhea | 2 (0) | [208] |

| 2001 | France | Raw milk semi-hard cheese | SED | Vomiting | 17 (0) | [208] |

| 2002 | France | Raw sheep’s milk cheese | SEA | Nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, and diarrhea | 43 (0) | [208] |

| 2007 | Switzerland | Robiola cheese | SEG, SEI, SEM, SEN, SEO | Nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, and diarrhea (in some cases) | 5 (0) | [202] |

| 2009 | France | Soft cheese | SEE | Nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, diarrhea, and fever (in some cases) | 23 (0) | [213] |

| 2009 | Italy | Soft raw sheep milk cheese | SEC | Vomiting and abdominal cramps | 2 (0) | [214] |

| 2011 | Italy | Soft raw sheep milk cheese | SEC | Nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, and diarrhea | 3 (0) | [214] |

| 2013 | Italy | Soft raw sheep milk cheese | SEC | Vomiting, abdominal cramps, and diarrhea | 6 (0) | [214] |

| 2014 | Switzerland | Tomme cheese | SEA, SED | Vomiting, abdominal cramps, severe diarrhea, and fever | 14 (0) | [202] |

| 2016 | Italy | Soft raw sheep milk cheese | SEC | Vomiting, abdominal cramps, and diarrhea | 6 (0) | [214] |

| 2018 | Italy | Alm cheese | SED | Vomiting, abdominal cramps, and diarrhea | 3 (0) | [215] |

| 2022 | Italy | Raw milk cheese | SEA, SEB, SEC, SED, SEE | Vomiting, diarrhea, and headaches | 8 (0) | [216] |

| Country or Region | Microbiological Criteria | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CoPS, S. aureus, or SEs | n | c | m | M | Notes | Reference | |

| Australia | CoPS | 5 | 2 | 100 | 1000 | All types of cheese | [229] |

| Brazil | CoPS | 5 | 2 | 100 | 1000 | All types of cheese | [230] |

| SEs | 5 | 0 | absence | - | All types of cheese | ||

| Canada | S. aureus | 5 | 2 | 1000 | 10,000 | Cheese made from an unpasteurized source | [231] |

| China | S. aureus | 5 | 2 | 100 | 1000 | All types of cheese | [232] |

| European Union | CoPS | 5 | 2 | 10,000 | 100,000 | Cheese made from raw milk | [233] |

| 5 | 2 | 100 | 1000 | Cheese made from mild heat treated milk | |||

| 5 | 2 | 10 | 100 | Unriped soft cheese made with pasteurized milk | |||

| United States | S. aureus | - | - | - | 10,000 | All dairy products | [234] |

| SEs | - | - | not detected | - | All dairy products | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ribeiro, A.C.; Tavares Alves, D.; Campos, G.Z.; da Costa, T.G.; Dora Gombossy de Melo Franco, B.; Almeida, F.A.d.; Pinto, U.M. Clarifying the Dual Role of Staphylococcus spp. in Cheese Production. Foods 2025, 14, 3823. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14223823

Ribeiro AC, Tavares Alves D, Campos GZ, da Costa TG, Dora Gombossy de Melo Franco B, Almeida FAd, Pinto UM. Clarifying the Dual Role of Staphylococcus spp. in Cheese Production. Foods. 2025; 14(22):3823. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14223823

Chicago/Turabian StyleRibeiro, Alessandra Casagrande, Déborah Tavares Alves, Gabriela Zampieri Campos, Talita Gomes da Costa, Bernadette Dora Gombossy de Melo Franco, Felipe Alves de Almeida, and Uelinton Manoel Pinto. 2025. "Clarifying the Dual Role of Staphylococcus spp. in Cheese Production" Foods 14, no. 22: 3823. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14223823

APA StyleRibeiro, A. C., Tavares Alves, D., Campos, G. Z., da Costa, T. G., Dora Gombossy de Melo Franco, B., Almeida, F. A. d., & Pinto, U. M. (2025). Clarifying the Dual Role of Staphylococcus spp. in Cheese Production. Foods, 14(22), 3823. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14223823