Abstract

In this study, we isolated 214 Vibrio cholerae strains from aquatic (shrimp, crab, grass carp, and crucian carp) and their cultured environment in Shanghai, China. The virulence, serotype, and antimicrobial susceptibility were tested, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was used to detect antimicrobial resistance genes. Enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus polymerase chain reaction (ERIC-PCR) was employed for cluster analysis of the isolated strains. The results showed that V. cholerae was found in 47.9% (114/238) of aquatic samples, with the highest detection rate in shrimp (81.1%), and the detection rate was highest in summer (70.0%). Most of the strains were non-O1/O139 groups, and virulence genes rtxC and hap had the highest detection rates of 92.5% and 91.1%. Of the 214 isolates, 69.6% were multidrug-resistant (MDR). The resistance rate of V. cholerae to sulfamethoxazole, ampicillin, and erythromycin was 97.2%, 85.5%, and 70.1%, and that to imipenem, tetracyclines, and aminoglycosides was less than 5%. The MAR index ranged from 0.05 to 0.47. When V. cholerae was screened for antimicrobial resistance genes, β-lactams CARB, chloramphenicol floR, and sulfonamides sul2 were found in 19.6%, 7.9%, and 6.5% of isolates, respectively. The results of ERIC-PCR clustering showed that the isolates had a high degree of genetic diversity. The widespread distribution of virulent and MDR V. cholerae strains poses a potential threat to food safety and public health, calling for improved monitoring and control measures in the aquaculture industry.

1. Introduction

As a highly adaptable Gram-negative bacterium, Vibrio cholerae inhabits aquatic products and marine environments across a wide global range of temperatures and salinities [1]. V. cholerae can cause cholera, a severe diarrheal disease that can be quickly fatal if untreated, and it is typically transmitted via contaminated water and person-to-person contact [2]. The increasing number of human infections caused by V. cholerae poses a serious threat to humans and the aquaculture industry [3]. Despite improvements in water quality, sanitation, and hygiene, as well as in the clinical treatment of cholera, the disease is still estimated to cause about 100,000 deaths every year [4].

Cholera, caused by the infection of toxigenic V. cholerae to humans, is a life-threatening diarrheal disease with epidemic and pandemic potential. V. cholerae, both O1 and O139 serogroups, produces a potent enterotoxin (cholera toxin) responsible for the lethal symptoms of the disease [5]. There are many virulence factors of V. cholerae. Two main virulence factors, cholera toxin (CT) and Toxin Coregulated Pilus (TCP), have been found in the O1 and O139 serotypes of V. cholerae that cause cholera epidemics [6]. CT causes diarrhea in patients, and TCP enables bacteria to adhere to the intestinal mucosa and form microcolonies [7]. Other virulence-related factors such as zonula occludens toxin (zot), accessory cholera enterotoxin (ace), repeats in toxin gene cluster (rtxA-D), hemolysin (hlyA), thermolabile hemolysin (tlh), heat-stable enterotoxin (stn/sto), hemagglutinin protease (hapA), outer membrane protein (ompU), mannose-sensitive hemagglutination pili (mshA), putative type IV pilus (pil), and ToxR regulatory proteins, etc., are also involved in the pathogenic process [6,8,9]. Although the mechanisms by which most V. cholerae causes diseases in aquatic products may differ from those in humans, it is still believed that there is a possibility of zoonotic diseases caused by toxic V. cholerae [8]. It has been confirmed that V. cholerae can be transmitted from the environment to humans through water sources and seafood [10].

In recent decades, the emergence of antimicrobial resistance in pathogens has been observed worldwide and has caused public health concerns. Antimicrobial resistance can occur frequently in aquaculture settings due to the widespread and disorderly use of antimicrobials. Antimicrobial-resistant strains could be harmful to human health because mobile genetic elements can spread resistance genes to other human pathogens through the food chain [11]. Antimicrobial resistance genes and pathogenic bacteria are often accompanied by wastewater discharge into aquatic cultural environments. Capkin et al. found that 92.45% of Escherichia coli isolated from trout farms was resistant to sulfamethoxazole, followed by ampicillin (47.79%) and imipenem (28.93%). At least one resistance gene was found in 70.8% of the bacteria, and 66.6% of the bacteria had two or more resistance genes. Approximately 36.54% of the bacteria that contained plasmids were able to transfer them to other bacteria [12]. Wu et al. detected bacteria in aquatic products collected from Zhejiang, China, of which 109 strains (80.15%) showed resistance to at least one antimicrobial, and 38 antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) were identified across all samples [13]. In addition, a previous study has shown that V. cholerae isolated from shrimp farming environments exhibited resistance rates of up to 46.6% for cephazolin, 30.7% for streptomycin, and 11.4% for ampicillin [14]. These findings suggest that aquatic environments may play a significant role in the development of antimicrobial resistance and the transmission of resistance genes among bacteria. Thus, aquatic bacteria, including pathogenic V. cholerae, can act as a repository of resistance genes and may be important to the transmission and evolution of antimicrobial genes in the aquatic cultured environment [15]. Antimicrobial resistance persists in aquatic systems, and its residues and cross-domain transmission pose a dual threat to ecosystems and human health. Aquatic foods may serve as carriers, guiding antimicrobial-resistant symbionts into the human gastrointestinal system, where they interact with the gut microbiota and spread antimicrobial resistance. The emergence of multiple-antimicrobial-resistant strains raises significant concerns regarding seafood safety and human health [16].

To support the consumption of aquatic products and provide guidance on the scientific use of medicines, it is crucial to improve the understanding of the occurrence and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of V. cholerae originating from aquatic sources. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the occurrence and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of V. cholerae strains in shrimp, grass carp, crucian carp, crab, and cultured environment samples from different districts in Shanghai. In addition, the virulence genes, antimicrobial genes, and genetic diversity of V. cholerae isolates were determined. These findings could help to predict potential human health risks associated with V. cholerae exposure and provide basic data for subsequent studies of resistance mechanisms.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

From June 2020 to October 2021, 238 aquatic product and aquaculture environment samples (cultured water and sediment of the corresponding aquatic products) were collected monthly from 27 aquaculture farms in 8 districts of Shanghai. Four categories of aquatic products, including shrimp, grass carp, crucian carp, and crab, were collected from farms. The types of shrimp culture were further categorized into greenhouse and open-air culture. The samples were pretreated as follows: For shrimp, the body surface was rinsed with tap water, and the excess water was removed. Sterile scissors were used to remove the shrimp shell, and the shrimp pancreas was picked out and put in a sterile bag (Interscience, Saint Nom la Bretèche, France). Grass carp and crucian carp were similarly rinsed; after drying, the fish’s belly was cut open with a sterile knife, and intestinal and gill contents were transferred to a sterile bag. Crabs were rinsed and dried, and then the shell was removed, and visceral and gill contents were collected in a sterile bag. After pretreatment of the collected samples, 25 mL (g) each of water/mud/fishery samples was placed in a homogenizing bag containing 225 mL of Alkaline Peptone Water (APW; Beijing Land Bridge Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) and beat for 2 min using a BagMixer 400 CC (Interscience, Saint Nom la Bretèche, France) to form sample homogenization for later use. A total of 82 aquaculture samples were collected from each farm, including 37 shrimp, 35 fishes, and 10 crabs; 79 cultured water samples and 77 cultured sediment samples were collected at the same time. The collected samples were categorized according to sample types, quarters, and districts (Table A1). In addition, water-quality-related information (salinity, temperature, pH) was measured by a DSM-5 salinity meter (Lichen Scientific Instruments Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), 2-3799-01 electronic thermometer (AS ONE, Shanghai, China), and PH-100pro pH meter (Lichen Scientific Instruments Co., Shanghai, China) for some of the farms [17].

2.2. Analysis of Vibrio Species

The strain isolation method referred to the “Testing methods for Vibrio cholerae in imported and exported food” (SN/T 1002-2010 [18]). For detection of Vibrio species, homogenized samples were transferred to 500 mL conical flasks and incubated overnight at 37 °C (8–18 h). The bacteria were picked with an inoculating loop and streaked on thiosulfate citrate bile salts sucrose agar culture medium (TCBS; Beijing Land Bridge Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) plates for 16–24 h. Subsequently, 3–5 suspected colonies of V. cholerae were picked from each plate and streaked on TCBS plates for 16–24 h. One suspected colony was picked from each plate and preserved in 25% glycerol (Sigma-Aldrich, Shanghai, China) at minus 80 degrees in a refrigerator pending further verification.

Genomic DNA was extracted from bacterial colonies using a Wizard Genomic DNA extraction kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Referring to Fu et al., the specific gene we selected for PCR was lolB (lolB-F: TGG GAG CAG CGT CCA TTG TG, lolB-R: CAA TCA CAC CAA GTC ACT C, 516 bp), with V. cholerae GIM 1.449 (lolB+) and V. cholerae CICC 23794 (lolB+) as positive control strains [19]. In addition, the serotype (O1 and O139) gene primers, product sizes, and annealing temperatures are shown in Table A2. The 25 μL PCR reaction system consisted of 12.5 μL of mix, 9.5 μL of dd water, 10 μmol/L of upstream and 1 μL of downstream primers each, and 1 μL of template. PCR amplification products were determined by 1.0% agarose gel electrophoresis.

2.3. Identification of Virulence Genes and Antimicrobial Resistance Genes

The presence of virulence and antimicrobial resistance genes in the V. cholerae isolates was determined through TProfessional Standard Thermocyler (Biometra, Göttingen, Germany) with a thermal cycler. The primers and PCR amplification conditions are shown in Table A2. Amplified samples were analyzed by electrophoresis in 1% agarose gel. The gel imaging system was applied for analysis of images.

2.4. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests of V. cholerae Isolates

The susceptibility of V. cholerae to various antimicrobial agents was determined through the micro broth dilution method according to the guidelines of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI M45-ED3). The antimicrobial concentrations and antimicrobial susceptibility judgement criteria selected for this study are shown in Table A3. The 17 antimicrobials we use are classified into 9 classes, namely, penicillins, carbapenems, cephalosporins, tetracyclines, chloramphenicol, sulfonamides, macrolides, aminoglycoside, and nitrofurans (Table A3). Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 was used as a quality control strain in antimicrobial susceptibility determination. The results were interpreted according to the CLSI M45 2016 edition guidelines for drug sensitivity and recorded as susceptible (S), intermediate (I), and resistant (R). Multiple-antimicrobial resistance (MAR) is defined as a measure indicating the level of antimicrobial resistance in organisms, specifically where an index greater than 0.2 points to origins from high-risk contamination sources. The MAR index of the isolates was defined as x/y, where x represents the number of antimicrobial agents to which the isolate was resistant, and y represents the total number of antimicrobial agents against which an individual isolate was tested [20]. Multidrug-resistant (MDR) was defined as acquired non-susceptibility to at least one agent in three or more antimicrobial categories, extensively drug-resistant (XDR) was defined as non-susceptibility to at least one agent in all but two or fewer antimicrobial categories (i.e., bacterial isolates remain susceptible to only one or two categories), and pandrug-resistant (PDR) was defined as non-susceptibility to all agents in all antimicrobial categories. The antimicrobial resistance pattern abundance (ARPA) was expressed as the total number of resistance spectrum types divided by the total number of strains.

2.5. Analysis of the Genetic Diversity of V. cholerae

Enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus polymerase chain reaction (ERIC-PCR) primer sequences and reaction conditions were carried out according to Mejdi et al. [21]; ERIC-PCR amplification primers were as follows: Eric1: 5′- ATG TAA GCT CCT GGG GAT TCA C-3′; Eric1: 5′- AAG TAA GTG ACT GGG GTG AGC G-3′; the 25 μL reaction system was as follows: mix 12.5 μL, dd H2O 8.5 μL, 10 μmol/L upstream and downstream primers 1 μL each, andtemplate 2 μL. Cycling parameters were as follows: pre-denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, then cycling 94 °C for 45 s, 52 °C for 1 min, and 72 °C for 1 min for 35 cycles. The final extension was 72 °C for 10 min. The amplification products were electrophoresed by 1% agarose gel (Tsingke, Beijing, China) at 100 V for 45 min, and then the electropherograms were analyzed by the gel imaging system. The presence of bands was recorded as 1, and the absence of bands was recorded as 0. The output results were analyzed using the unweighted pair-group method with arithmetic means (UPGMA) in the NTsys-pc software Version 2.10e (New York, NY, USA).

The Simpson Index is used to express species diversity and is calculated using the following formula:

where N is the total number of strains, S is the total number of ERIC genotypes, and Xj is the number of genes in the jth ERIC genotype.

2.6. Data Processing and Analysis

In this paper, data results statistics were processed and produced using the GraphPad Prism software 10.1.2 (San Diego, CA, USA), gel electrophoresis plots were generated using the Geldoc XR+ Gel Imaging system (Hercules, CA, USA), and significant difference calculations were produced using the SPSS 25.0 software (New York, NY, USA). The normal distribution of the data was tested using SPSS, and the significance of the data differences was compared by a t-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA). p < 0.05 was considered statistically different.

3. Results

3.1. Water Temperature, pH, and Salinity

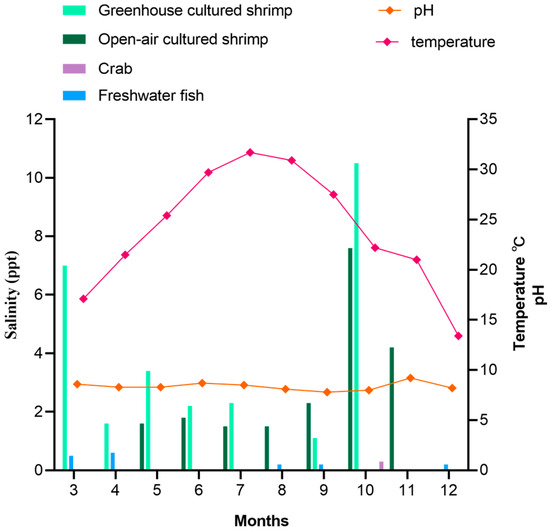

Figure 1 shows the monthly variations in the water temperature, pH, and cultured salinity at different cultivation farms from 2019 to 2020. The monthly mean values of water temperature, pH, and salinity ranged from 13.7 °C to 32.2 °C, 8 to 9, and from 1.1 ppt to 10.5 ppt. The water temperatures were markedly higher during the summer, especially in July. However, the pH did not exhibit large seasonal variations. Moreover, the salinity of shrimp culture environments was significantly higher than that of other aquatic product cultured environments, which was below 1.0 ppt.

Figure 1.

Average physical and chemical information change in farms in different months.

3.2. Distribution and Serotypes of V. cholerae

Table 1 shows that 214 V. cholerae strains were detected in 114 (47.9%) out of 238 aquatic samples. Among them, 159 and 55 V. cholerae strains were detected in 81 (71.7%) shrimp samples and 33 (37.9%) freshwater fish samples. V. cholerae was not detected in crab samples and its cultured environment. Of the three tested types of aquatic samples, the detection rate was highest in shrimp (81.1%), followed by grass carp (38.9%), and crucian carp (29.4%). There was no significant difference between the V. cholerae detection rate in aquatic samples and environmental samples (p > 0.05).

Table 1.

Distribution of V. cholerae in 238 aquatic samples.

The detection rate of V. cholerae in different seasons is shown in Table 2. The highest detection rate was 70.0% in summer, followed by spring (54.8%), autumn (39.1%), and winter (12.1%). Among aquatic product samples, the detection rate in greenhouse-cultured shrimp was 100.0% in summer and autumn, with a 75.0% detection rate in spring; the detection rate in open-air-cultured shrimp decreased from 100.0% in spring to 66.7% in autumn. Likewise, the detection rate in grass carp was highest in summer (80.0%). Moreover, in crucian carp, the detection rates were all below 50.0%. Among the environmental samples, the detection rate in the greenhouse-cultured shrimp environmental samples was highest in summer and autumn, while in the open-air-cultured shrimp environmental samples, it was highest in spring. The detection rate of V. cholerae in freshwater fish environmental samples was higher than 50.0% in summer and 100.0% in autumn.

Table 2.

Detection rates of V. cholerae in samples from different seasons.

Except for three V. cholerae strains (Vc381, Vc382, Vc383), which were confirmed as the O139 serotype, the remaining 211 V. cholerae strains in the present study were confirmed as non-O1 and non-O139 species. O139-serotype V. cholerae strains were isolated from the shrimp aquaculture water samples in summer.

3.3. Virulence Genes of V. cholerae Isolates

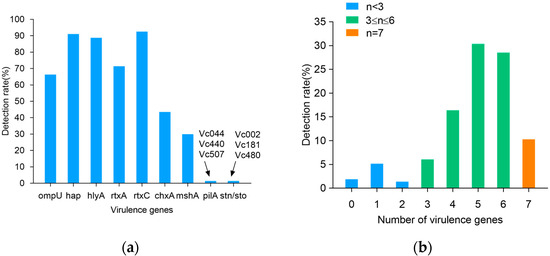

Figure 2 summarizes the presence of virulence genes in the V. cholerae isolates. A total of nine virulence genes were detected, and the virulence genes ctxA, ctxB, ctxAB, tcpA, ace, and zot were detected in none of the isolates. Among the nine detected genes, rtxC, and hap had the highest detection rates of 92.5% and 91.1%, followed by hlyA, rtxA, ompU, chxA, and mshA, with 88.8%, 71.5%, 66.4%, 43.5%, and 29.9% (Figure 2a). The detection rate of pilA and stn/sto was extremely low, and they were, respectively, detected only in three isolates (Vc002, Vc181, and Vc480, and Vc044, Vc440, and Vc507). As shown in Figure 2b, 214 strains of V. cholerae carried several virulence genes, ranging from 0–7. Among them, 8.4% (n = 18) of the strains carried less than three virulence genes, the majority of the V. cholerae (81.3%) carried four to six virulence genes, and 10.3% (n = 22) carried seven virulence genes.

Figure 2.

Virulence genes detection rates of 214 V. cholerae strains. (a) Detection rate of virulence genes; (b) number of virulence genes.

The virulence genes of 210 V. cholerae strains exhibited 31 virulence patterns (Table 3). Among them, V. cholerae, carrying five virulence genes with a virulence pattern of hap, hlyA, rtxA, rtxC, and ompU, had the highest percentage of 19.2%. This was followed by 13.1% of V. cholerae carrying six virulence genes, with a virulence pattern of hap, hlyA, rtxA, rtxC, ompU, and chxA. Finally, the virulence profiles of the 20 V. cholerae strains carrying seven virulence genes were hap, hlyA, rtxA, rtxC, ompU, chxA, and mshA in 9.3%. Overall, there was diversity in the pattern of V. cholerae virulence gene carriage.

Table 3.

Virulence patterns of 214 V. cholerae strains.

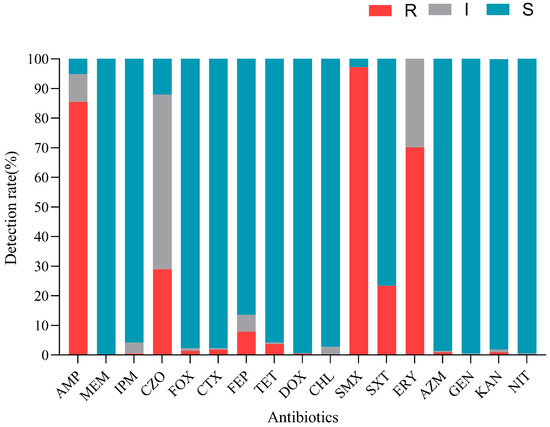

3.4. Antimicrobial Resistance Patterns of V. cholerae Isolates and Analysis of V. cholerae Resistance in Different Aquatic Samples

To determine the antimicrobial resistance patterns of V. cholerae isolates, 17 antimicrobials were chosen for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. The results showed that strains were resistant to 13 antimicrobials of seven classes. As shown in Figure 3, among the 214 V. cholerae isolates tested, 97.2% were resistant to sulfamethoxazole (SMX), representing the highest resistance to antimicrobials used in this study. In addition, the isolates exhibited relatively high resistance to ampicillin (AMP) (85.5%), erythromycin (ERY) (70.1%), cefazolin (CZO) (29.0%), and cotrimoxazole (SXT) (23.4%). Moreover, among the cephalosporin antimicrobials, the isolates exhibited the highest resistance to CZO (29.0%), followed by cefepime (FEP) (7.9%), and less than 5% of the isolates were resistant to cefoxitin (FOX) and cefotaxime (CTX). Meanwhile, isolates showed low resistance to five antimicrobials (imipenem (IPM), tetracycline (TET), doxycycline (DOX), azithromycin (AZM), and kanamycin (KAN)) (<5%). All isolates were sensitive to meropenem (MEM). A small number of isolates exhibited intermediate resistance to chloromycetin (CHL), gentamycin (GEN), and nitrofurantoin (NIT), and more than 90.0% of isolates were susceptible to IPM, FOX, CTX, AZM, CHL, TET, DOX, GEN, and KAN. The results showed that V. cholerae isolated from aquatic products and the culture environment was only resistant to some antimicrobials, and it did not show an all-around high level of antimicrobial resistance.

Figure 3.

Antimicrobial sensitivity of 214 V. cholerae strains.

The strains exhibited 39 resistance patterns, with an antimicrobial resistance pattern abundance (ARPA) of 0.18 and 69.6% of MDR strains (Table 4). In addition, none of the strains were XDR or PDR. The main resistance pattern was AMP-SMX-ERY (n = 66), followed by AMP-SMX (n = 28) and AMP-CZO-SMX-ERY (n = 23).

Table 4.

Antimicrobial resistance patterns of 214 V. cholerae strains.

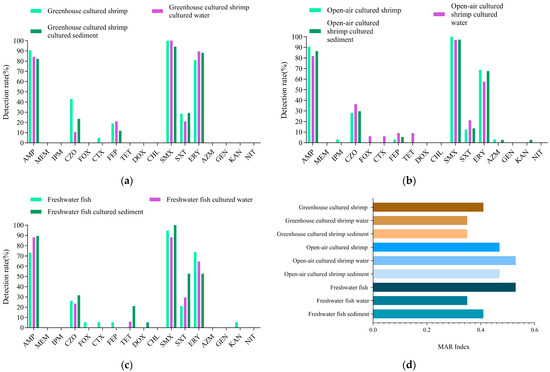

3.5. Antimicrobial Resistance Analysis of V. cholerae in Shrimp and Fish

To determine V. cholerae resistance in shrimp, antimicrobial susceptibility tests for V. cholerae were conducted. As shown in Figure 4a, the 57 strains of V. cholerae in greenhouse-cultured shrimp, water, and sediment showed varying resistance rates to seven antimicrobials of four classes. Notably, they showed over 80% resistance to AMP, ERY, and SMX, while resistance to CZO, FEP, and SXT ranged from 10% to 50%. Only one strain (Vc001) was resistant to CTX. The MAR index was 0.41 for shrimp, 0.35 for water, and 0.35 for sediment, thus suggesting slightly higher contamination in shrimp compared to its cultured environment (Figure 4d).

Figure 4.

Antimicrobial resistance analysis of V. cholerae from shrimp, freshwater fish, and their environmental samples. (a) The antimicrobial resistance rate of V.cholerae from greenhouse cultured shrimp; (b) The antimicrobial resistance rate of V.cholerae from Open-air cultured shrimp; (c) The antimicrobial resistance rate of V.cholerae from freshwater fish; (d) The MAR Indexes of V.cholerae from shrimp, freshwater fish, and their environmental samples.

Figure 4b shows the sensitivity of 102 V. cholerae strains from open-air-cultured shrimp, water, and sediment to 12 antimicrobials of seven classes. V. cholerae from shrimp was resistant to eight antimicrobials of five classes, while V. cholerae from water and sediment were resistant to nine and eight antimicrobials of five classes. V. cholerae from shrimp and the environment showed more than 95% resistance to SMX, 50–90% to AMP and ERY, and less than 50% to CZO, FEP, and SXT. V. cholerae from shrimp had a 3.1% resistance rate to IPM, FEP, and AZM. V. cholerae from water showed resistance to all four generations of cephalosporins, with the highest resistance rate (36.4%) to CZO. Resistance to FOX, CTX, and FEP was 6.1% (n = 2), 6.1% (n = 2), and 9.1% (n = 3). In addition, they also showed 9.1% resistance to TET. V. cholerae from sediment had a 2.7% (n = 1) resistance rate to AZM and KAN. The MAR indexes of open-air-cultured shrimp, water, and sediment were 0.47, 0.53, and 0.47, indicating higher antimicrobial contamination in water than in shrimp and sediment (Figure 4d).

Figure 4c shows that strains from freshwater fish, water, and sediment were resistant to 11 antimicrobials of six classes, with V. cholerae from freshwater fish resistant to 9 antimicrobials of five classes, and V. cholerae from the environment resistant to 7 antimicrobials. All strains showed high resistance to AMP, SMX, and ERY (50–100%) and low resistance to CZO and SXT. In addition, they showed resistance to all four generations of cephalosporins, with the highest resistance to first-generation CZO (26.3%) and lower resistance to other generations (5.3%). Resistance to aminoglycoside KAN was 5.3%. Tetracycline-resistant strains were detected only in cultured environmental samples. The MAR index for V. cholerae from freshwater fish was 0.53, higher than 0.35 for water and 0.41 for sediment (Figure 4d).

3.6. Detection of V. cholerae Drug Resistance Genes

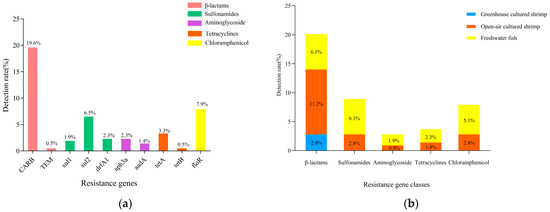

A total of 10 drug resistance genes of five classes were detected in 214 V. cholerae strains (Figure 5a). β-lactams CARB, chloramphenicol floR, and sulfonamides sul2 were detected at 19.6%, 7.9%, and 6.5%. β-lactams (TEM), sulfonamides (sul1, drfA1), aminoglycosides (aph3a, aadA), and tetracyclines (tetA, tetB) had resistance gene detection rates below 5%.

Figure 5.

Results of resistance genes of V. cholerae in aquatic products and environmental samples. (a) Resistance genes; (b) resistance gene classes.

As shown in Figure 5b, only β-lactam resistance genes were detected in V. cholerae in greenhouse-cultured shrimp. In contrast, five classes of resistance genes were detected in V. cholerae in open-air-cultured shrimp and freshwater fish. Among them, β-lactams dominated the resistance genes of V. cholerae in open-air-cultured shrimp, with detection rates of 11.2%. In freshwater fish, the detection rate of β-lactam resistance genes and sulfonamide resistance genes were the highest (6.1%), followed by chloramphenicol (5.1%) and tetracyclines (2.3%).

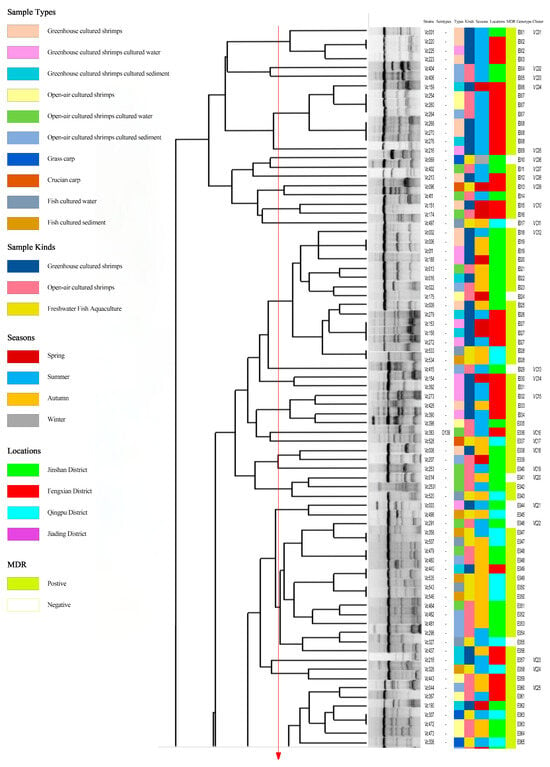

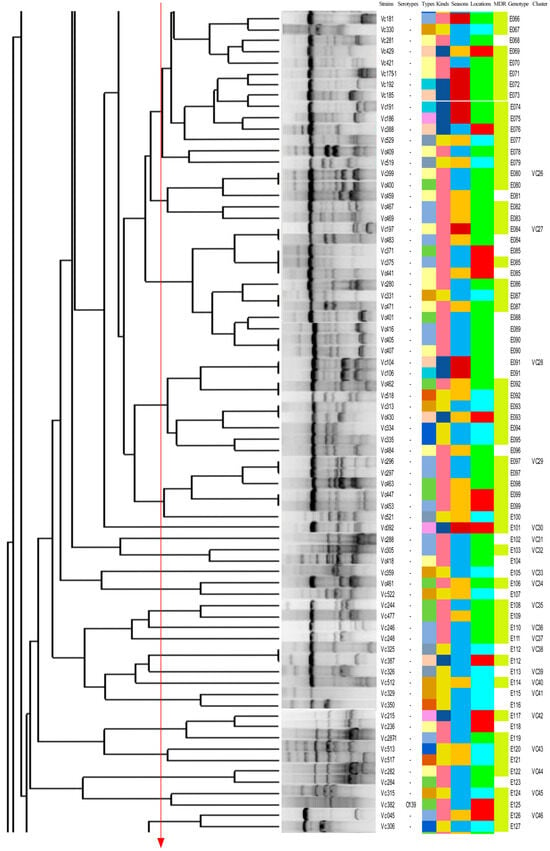

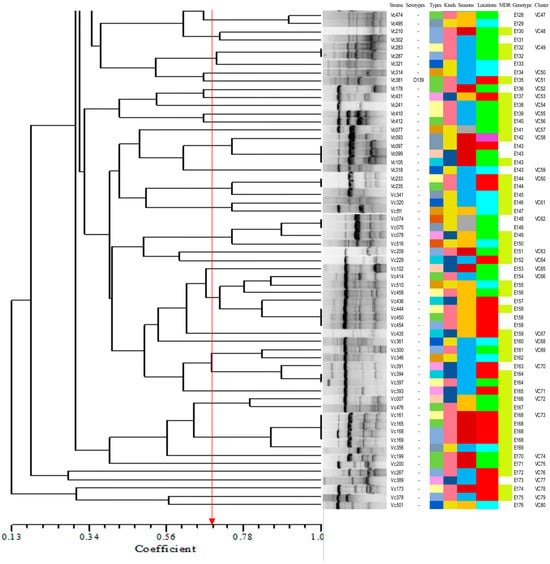

3.7. Analysis of Genetic Diversity

Figure 6 shows the ERIC-PCR clustering results for 214 V. cholerae strains, with strain similarity ranging from 13% to 100%, clustering into 177 ERIC genotypes (E001-E177), where 69.2% (148/214) were single genotypes. A total of 26.5% (39/148), 46.9% (69/148), and 27.0% (40/148) of the single genotypes were from greenhouse-cultured shrimp, open-air-cultured shrimp, and freshwater fish; 16.3% (24/148), 50.7% (75/148), 32.0% (47/148), and 1.4% (2/148) of the single genotypes were from spring, summer, and fall. Strains with similarity coefficients ≥0.69 were defined as identical groups (marked by red solid lines). The 177 ERIC genotypes were clustered into 80 distinct groups (Vc01-Vc80), 43 of which contained only one ERIC genotype. All ERIC genotypes contained less than five strains, with no clear dominant ERIC type; of the 80 groups, group Vc25 was the most dominant group, containing 9.8% (21/214) of the strains. There were significant differences between ERIC genotypes and sample types, sampling times, and serotypes (p < 0.05). This suggested that the 214 V. cholerae strains were highly genetically diverse, showing significant differences in genotypic composition across serotypes, species of aquatic product, and time.

Figure 6.

Dendrogram of 214 V. cholerae by using ERIC-PCR.

4. Discussion

Cholera caused by V. cholerae continues to pose a global threat, despite improvements in sanitation and treatment methods, and it remains a significant public health issue. The emergence and spread of antimicrobial resistance in aquatic environments, coupled with the overuse of antimicrobials in aquaculture, further exacerbate the threat to human health. Therefore, it is necessary to assess the prevalence, antimicrobial susceptibility, pathogenic genes, and genetic diversity of V. cholerae in aquatic products and aquaculture environments, which will help evaluate potential health risks and provide foundational data for understanding resistance mechanisms.

V. cholerae was detected in all seasons, and the detection rate in different seasons was highest in summer and lowest in winter. There were significant differences in V. cholerae detection rates between different seasons (p < 0.05). Our study showed that environmental temperature can significantly affect V. cholerae abundance. These findings are consistent with previous research showing that V. cholerae abundance correlates to temperature, and Vibrio species display preferences for warm tropical water in summer [22]. In addition, heavy rainfall during the summer months reduces the salinity of water, which directly affects the detection rate of V. cholerae.

In this study, the results suggest that shrimp is more likely to be a host for V. cholerae. The main reason may be that compared to freshwater fish and crab culture environments, the salinity of shrimp culture environments is higher. It has been reported that the salinity of an environment significantly correlates with V. cholerae incidence [23,24]. Another study has shown that a sharp fall in the cultivable count of V. cholerae during monsoon is attributed to reduced salinity [25]. The optimal salinity range for V. cholerae growth is 15–25 ppt [26]. In this study, the salinity of the shrimp culture environment was between 1.1 and 10.5 ppt (Figure 1), while salinities in freshwater fish and crab culture environments were generally below 1.0 ppt, which is not favorable for V. cholerae growth. Ahmed et al. collected 132 shrimp samples from a market, in which the V. cholerae detection rate was 1.5% much lower than this study [27]. This evidence is concerning because it shows that V. cholerae is highly prevalent in aquaculture.

Cholera enterotoxin is the primary virulence factor of the disease cholera, which is caused by infection with toxigenic V. cholerae serotypes O1 or O139. The other serotypes are collectively known as non-O1/O139 V. cholerae. In this study, V. cholerae strains were mainly non-O1/O139 serotypes, and the main virulence genes ctxA/B/AB and tcpA were detected in none of the 214 V. cholerae strains. Similarly, a study indicated that very few non-O1/O139 V. cholerae isolates from clinical sources had the TCP and CTX gene cassettes [9]. Most previous studies focused on the harm caused by V. cholerae strains of serotypes O1 or O139. However, previous research has shown that four resistance-associated genes (strB, dfrA1, sulll, SXT) were confirmed to have a higher prevalence in V. cholerae non-O1/non-O139 strains [28]. These results demonstrate a potential threat of non-O1/O139 V. cholerae in aquatic products. Therefore, there is a need for continuous testing of non-O1/O139-serotype V. cholerae prevalence in aquaculture environmental sources.

The carriage of virulence genes and pathogenicity factors is an indicator of strain virulence assessment. In addition to the main ctxAB and tcpA virulence genes, other virulence genes play important roles in V. cholerae pathogenesis [28]. In this study, the detection rates of the HAP and rtxC were extremely high, exceeding 90%. The detection of rtxC in the current study is similar to some earlier studies [29,30,31]. Among them, HAP encodes a hemagglutinin protease that degrades host cell intercellular adhesion proteins and enhances bacterial invasion capacity [32]. In non-O1O139 V. cholerae infections, HAP protease directly causes intestinal epithelial cell detachment and inflammatory responses, leading to watery diarrhea, abdominal pain, and bloody stools [8]. RtxA belongs to the same RTX toxin gene cluster as rtxC, which disrupts host cell membrane integrity through a perforation mechanism and leads to permanent dissociation of the cytoskeleton [33]. In immunocompromised individuals, RTX toxin may promote bacterial entry into the bloodstream, leading to sepsis. Meyer et al. found that all 29 clinical isolates carrying rtxA were associated with extraintestinal infections [34]. The actin cross-linking repeats in the toxin gene cluster (rtx) lead to actin depolymerization when cross-linked with Hep-2, and this causes villi effacement, hemorrhagic colitis, and bloody diarrhea, as reported earlier [35,36]. The detection rate of hlyA was relatively high at 71.5%. The prevalence of hlyA in our study is similar to that of earlier studies from clinical and environmental samples [31,37,38]. HlyA is involved in cellular infection through the modulation of hemolysins, and hlyA hemolysin promotes bacterial proliferation by lysing red blood cells to release iron ions [39,40]. The results of this study are consistent with the results of the detection of V. cholerae virulence genes isolated from common aquatic products from Shanghai supermarkets by Xu et al. and Fu et al. [6,19]. The detection of these virulence genes suggests that V. cholerae has multiple pathogenic potentials: initially, it establishes infection foci through adhesion of bacterial hairs, then releases multiple toxins to disrupt the intestinal barrier function, and ultimately leads to severe diarrhea, electrolyte disorders, and systemic toxicity symptoms [3,41,42]. In particular, the synergistic effect of RTX toxins and hemolysin may aggravate intestinal mucosal damage and systemic inflammatory response [43]. It can be seen that there is diversity in the pattern of V. cholerae virulence gene carriage in an aquaculture environment. The detection of multiple related virulence genes of V. cholerae constitutes the genetic basis for causing symptoms such as mild gastroenteritis or even severe diarrhea. Non-major virulence genes provide the genetic basis for causing mild gastroenteritis and even severe diarrhea, which need to be guarded against.

Antimicrobial resistance assessment under pathogens and its potential ecology risk is a major worldwide concern for medicine research and development [44]. The results showed that the strains of V. cholerae were resistant to 13 antimicrobials of seven classes, indicating that V. cholerae had developed multidrug resistance in the aquatic culture environment. This is consistent with previous studies, which have found that V. cholerae from aquatic products from seafood markets are highly resistant to penicillin (P), AMP, and amoxicillin (AMOX) [37]. Additionally, Wu et al. found the highest resistance rate in erythromycin (36%) among all tested macrolide antimicrobials in O1/O139 V. cholerae [45]. Another study recorded high rates of resistance in environmental V.cholerae isolates to beta-lactams (penicillin and 15 isolates for ampicillin) and streptomycin [7]. The high resistance rates (>70%) of SMX, AMP, and ERY can be attributed to their overuse in aquaculture and clinical settings. Dua et al. found that non-O1/O139-serotype V. cholerae strains from Indian clinical settings have developed widespread resistance to antimicrobials, including AMP, CHL, TET, and SMX, similar to the results of this study [9]. The 23.4% resistance rate of SXT also suggests that it may be overused. Similar to the results in our study, it has been found that the weighted pooled resistance (WPR) rate of non-O1O139 V. cholerae from clinical origins to cotrimoxazole is 27% [45]. Compared to Gram-positive bacteria, Gram-negative bacteria are less permeable, and their outer membrane naturally forms a permeability barrier against antimicrobials [46]. It is worth noting that approximately 75% of antimicrobials used in aquaculture enter the environment through feces and feed and accumulate there, potentially driving the development of bacterial resistance [47]. In this study, there were different levels of resistance rates (<5%) to main types of antimicrobials (DOX and CTX), which suggested that there was a certain degree of antimicrobial pollution in the cultured environment. On the whole, the sensitivity of V. cholerae to DOX, IPM, MEM, CHL, and other first-line drugs for clinical treatment was higher than 90%. Tetracyclines have been the most effective antimicrobial class in treating cholera for a long time [45]. The sensitivity rate of aminoglycosides (GEN, KAN), macrolides (AZM), nitrofurans (NIT), and second-, third-, and fourth-generation cephalosporins (FOX, CTX, FEP), except CZO, was higher than 85%, which provides multiple options for clinical medication.

The ranking of V. cholerae antimicrobial resistance levels in different aquatic products is as follows: greenhouse shrimp > grass carp > open-air shrimp = crucian carp. The MAR index for all strains is higher than 0.2, indicating that V. cholerae in the current aquaculture environment is exposed to high levels of antimicrobial contamination. Open-air-cultured shrimp require particular attention. Due to human activities, bacterial resistance is continuously evolving. Therefore, regular monitoring of antimicrobial resistance in aquaculture areas is crucial for ensuring the quality and safety of aquatic products.

This study detected 10 drug resistance genes in five classes. Among these, the detection rate for the β-lactam resistance gene CARB was the highest (19.6%), and that for the β-lactam resistance gene blaTEM was 0.5%. The resistance gene CARB was found to be responsible for penicillin resistance; it is one of the class A β-lactamases that exhibit a broad substrate hydrolysis profile against penicillins [48]. In addition, the resistance rate of penicillin antimicrobial AMP was extremely high in this study. The detection rate of the chloramphenicol resistance gene floR was 7.9%, corresponding to the low resistance rate of chloramphenicol CHL (<5%). In addition, the detection rates of sulfonamide resistance genes sul2, drfA1, and sul1 were 6.5%, 2.3%, and 1.9%, respectively, while the resistance rate of sulfonamide antimicrobials was extremely high. This suggests there might be other antimicrobial resistance mechanisms such as efflux pump (either singly or in synergy with resistance genes) to archive antimicrobials resistance. The energy-dependent efflux of multiple antimicrobial agents from bacterial cells of the Vibrio spp. is a widely recognized resistance mechanism [49]. In addition, the low detection rate of tetracycline and chloramphenicol resistance genes corresponded to the low resistance rate. In summary, this non-corresponding relationship may be due to the wide variety of drug resistance genes, the existence of multiple alleles, and the fact that V. cholerae has a variety of drug resistance mechanisms, resulting in different correlations between drug resistance phenotypes and genotypes. Previous studies have shown that the emergence of V. cholerae resistance is mainly promoted by autonomously transmitted, autonomously replicated plasmids or horizontal gene transfer (HGT), which integrate mobile genetic elements [46]. Therefore, it is still necessary to pay attention to the spread of antimicrobial resistance and drug resistance of strains.

Many studies have shown that ERIC-PCR exhibits an excellent typing effect in foodborne pathogens and has been widely used in the study of V. cholerae molecular typing [6,19,50]. In our study, 214 V. cholerae strains in the aquaculture environment of Shanghai were scattered, and the homology was low. The differences in sample type and isolation time of the strains contained in the same genotype showed that there was a genetic relationship between V. cholerae isolates from different aquatic products. Through ERIC-PCR, 214 V. cholerae strains were divided into 80 different populations (Vc01-Vc80), of which 53.8% (43/70) contained only one ERIC genotype. Most of the populations and ERIC genotypes contained no more than five strains, indicating that V. cholerae in the aquatic cultural environment has a high genetic diversity.

5. Conclusions

V. cholerae strains are of particular concern because they pose a major threat to human health worldwide, primarily through the consumption of raw or undercooked seafood. V. cholerae was widely distributed across different water samples in Shanghai, with the highest detection rate in shrimp samples and peak prevalence during summer. The vast majority of serotypes were non-O1/O139. V. cholerae exhibited high resistance to the penicillin antimicrobial AMP, cephalosporin antimicrobial CZO, sulfonamide antimicrobials SMX and SXT, and macrolide antimicrobial ERY, without indicating high antimicrobial contamination levels. These several antimicrobials already have relatively high pollution levels in the aquaculture environment and are not suitable for continued use. Virulence genes of rtxC, hap, hlyA, and rtxA were highly prevalent. V. cholerae exhibited high genetic diversity, with significant differences in genotypic composition across serotypes, sample types, and seasons. Our study enriches the epidemic research data of V. cholerae in the aquaculture environment and is of certain significance for the continuous monitoring and risk factor identification of V. cholerae contamination in the aquaculture environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L. and X.S.; methodology, J.L.; software, J.L.; validation, Y.L. and J.L.; formal analysis, Y.L.; investigation, J.L.; resources, X.S. and W.L.; data curation, J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L. and X.S.; writing—review and editing, Y.L., X.Y., and X.S.; visualization, Y.L.; supervision, X.S. and W.L.; project administration, Y.Z. and W.L.; funding acquisition, X.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Key Research and Development Program of China, grant number 2024YFD2402204.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Statistical classification table of samples in different quarters and different districts.

Table A1.

Statistical classification table of samples in different quarters and different districts.

| Type of Samples (Total Sample Numbers) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Numbers in Different Quarters | Sample Numbers in Different Districts | ||||||||||

| Spring | Summer | Autumn | Winter | Jinshan District | Fengxian District | Qingpu District | Chongming District | Pudong New District | Jiading District | Baoshan District | Songjiang District |

| Greenhouse-cultured shrimp (n = 13) | |||||||||||

| 4 | 6 | 3 | - | 7 | 6 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Greenhouse-cultured shrimp culture water (n = 13) | |||||||||||

| 5 | 5 | 3 | - | 6 | 7 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Greenhouse-shrimp culture sediment (n = 13) | |||||||||||

| 5 | 5 | 3 | - | 6 | 7 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Open-air-cultured shrimp (n = 24) | |||||||||||

| 4 | 14 | 6 | - | 13 | 11 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Open-air-cultured shrimp culture water (n = 25) | |||||||||||

| 4 | 14 | 7 | - | 15 | 10 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Open-air-cultured shrimp culture sediment (n = 25) | |||||||||||

| 4 | 14 | 7 | - | 15 | 10 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Grass carp (n = 18) | |||||||||||

| 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 14 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Crucian carp (n = 17) | |||||||||||

| 3 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 12 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Fish culture water (n = 27) | |||||||||||

| 6 | 5 | 5 | 11 | 5 | 2 | 18 | - | - | 2 | - | - |

| Fish culture sediment (n = 25) | |||||||||||

| 4 | 5 | 5 | 11 | 5 | - | 18 | - | - | 2 | - | - |

| Crab (n = 10) | |||||||||||

| - | - | 10 | - | - | - | 3 | 3 | 2 | - | 1 | 1 |

| Crab culture water (n = 14) | |||||||||||

| - | - | 14 | - | - | - | 3 | 5 | 3 | - | 2 | 1 |

| Crab culture sediment (n = 14) | |||||||||||

| - | - | 14 | - | - | - | 3 | 5 | 3 | - | 2 | 1 |

| Total (n = 238) | |||||||||||

Table A2.

Primers of V. cholerae for virulence genes, serotype genes, and antimicrobial resistance genes.

Table A2.

Primers of V. cholerae for virulence genes, serotype genes, and antimicrobial resistance genes.

| Primer Name | Sequences (5′–3′), F/R | Annealing Temperature (°C) | Fragment Size (bp) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serotype | ||||

| O1 | GTTTCACTGAACAGATGGG | 59 | 192 | [51] |

| GGTCATCTGTAAGTACAAC | ||||

| O139 | AGCCTCTTTATTACGGGTGG | 59 | 449 | [51] |

| GTCAAACCCGATCGTAAAGG | ||||

| Virulence gene | ||||

| ctxA | CTCAGACGGGATTTGTTAGGCACG | 55 | 302 | [8] |

| TCTATCTCTGTAGCCCCTATTACG | ||||

| ctxB | GGTTGCTTCTCATCATCGAACCAC | 58 | 460 | [8] |

| GATACACATAATAGAATTAAGGAT | ||||

| ctxAB | TGAAATAAAGCAGTCAGGTG | 50 | 778 | [19] |

| GGTATTCTGCACACAAATCAG | ||||

| tcpA | ATGCAATTATTAAAACAGCTTTTTAAG | 52 | 675 | [19] |

| TTAGCTGTTACCAAATGCAACAG | ||||

| ace | GCTTATGATGGACACCCTTTA | 55 | 283 | [8] |

| GTTTAACGCTCGCAGGGCAAA | ||||

| zot | CACTGTTGGTGATGAGCGTTATCG | 56 | 244 | [8] |

| TTTCACTTCTACCCACAGCGCTTG | ||||

| hap | GTGAACAACACGCTGGAGAA | 50 | 700 | [8] |

| CGTTGATATCCACCAAAGG | ||||

| hlyA | CAATCGTTGCGCAATCGCG | 50 | 265 | [8] |

| TTGACCTTCAGCATCACT | ||||

| rtxA | GATTCTTCCGTTCAAGCTCCG | 60 | 2751 | [8] |

| TGGTTCAGGCTGTTGCACAC | ||||

| rtxC | CGACGAAGATCATTGACGAC | 50 | 263 | [8] |

| CATCGTCGTTATGTGGTTGC | ||||

| ompU | CCAAAGCGGTGACAAAGC | 50 | 655 | [8] |

| TTCCATGCGGTAAGAAGC | ||||

| chxA | TGGTGAAGATTCTCCTGCAA | 50 | 421 | [52] |

| CTTGGAGAAATGGATGCGCTG | ||||

| mshA | AAAAGTCGACAGCGAAAGCGAATAGTGG | 50 | 380 | [52] |

| AAAAGGATCCATTGCACCAGCAACTGCACC | ||||

| pilA | GCGATTGCAATTCCTCAA | 56 | 227 | [19] |

| CCTAATGCACCTGATGCT | ||||

| stn/sto | TCGCATTTAGCCAAACAGTAGAAA | 50 | 172 | [52] |

| GCTGGATTGCAACATATTTCGC | ||||

| Antimicrobial resistance gene | ||||

| β-lactams | ||||

| CARB | CAAGTACTTTYAAAACAATAGC | 48 | 535 | [53] |

| GCTGTAATACTCCKAGCAC | ||||

| blaSHV | GCGAAAGCCAGCTGTCGGGC | 62 | 304 | [54] |

| GATTGGCGGCGCTGTTATCGC | ||||

| blaTEM | ATAAAATTCTTGAAGACGAAA | 50 | 1080 | [55] |

| GACAGTTACCAATGCTTAATC | ||||

| NDM-1 | GGTTTGGCGATCTGGTTTTC | 52 | 621 | [56] |

| CGGAATGGCTCATCACGATC | ||||

| blaCTX-M | CGCTTTGCGATGTGCAG | 52 | 550 | [55] |

| ACCGCGATATCGTTGGT | ||||

| AmpC | TGATTAGCGTGTCCTATGGTGA | 60 | 1373 | [57] |

| GTCAGTAAGGCCCCCTGTTT | ||||

| Sulfonamides | ||||

| sul1 | AGGGGGC AGATGTGATCGC | 55 | 626 | [58] |

| TGTGCGGATGAAGTCAGCTCC | ||||

| sul2 | TCCGGTGGAGGCCGGTATCTGG | 55 | 191 | [58] |

| CGGGAATGCCATCTGCCTTGAG | ||||

| sul3 | TCCGTTCAGCGAATTGGTGCAG | 58 | 128 | [59] |

| TTCGTTCACGCCTTACACCAGC | ||||

| sulA | TCTTGAGCAAGCACTCCAGCAG | 58 | 299 | [59] |

| TCCAGCCTTAGCAACCACATGG | ||||

| dfrA1 | CAAGTTTACATCTGACAATGAGAACGTAT | 60 | 277 | [60] |

| ACCCTTTTGCCAGATTTGGTA | ||||

| dfrA18 | ACTGCCGTTTTCGATAATGTGG | 60 | 389 | [60] |

| TGGGTAAGACACTCGTCATGGG | ||||

| Macrolides | ||||

| ermB | AAAACTTACCCGCCATACCA | 55 | 141 | [54] |

| TTTGGCGTGTTTCATTGCTT | ||||

| ermC | GAAATCGGCTCAGGAAAAGG | 55 | 185 | [59] |

| TAGCAAACCCGTATTCCACG | ||||

| mefA | ATACCCCAGCACTCAATTCG | 56 | 186 | [61] |

| CAATCACAGCACCCAATACG | ||||

| mefC | GCTCCGGCACTACAGGCAAT | 56 | 117 | [62] |

| GCCAATGGCAGGACCACCAA | ||||

| Aminoglycoside | ||||

| aph3a | TAACAGCGATCGCGTATTTCG | 52 | 250 | [62] |

| TCCGACTCGTCCAACATCAATA | ||||

| aac(6′)-Ib | TATGAGTGGCTAAATCGAT | 55 | 395 | [63] |

| CCCGCTTTCTCGTAGCA | ||||

| armA | AGGTTGTTTCCATTTCTGAG | 53 | 591 | [64] |

| TCTCTTCCATTCCCTTCTCC | ||||

| rmtB | ATGAACATCAACGATGCCCT | 56 | 769 | [63] |

| CCTTCTGATTGGCTTATCCA | ||||

| aadA | ATCCTTCGGCGCGATTTTG | 56 | 283 | [65] |

| GCAGCGCAATGACATTCTTG | ||||

| aadE | ATGGAATTATTCCCACCTGA | 50 | 386 | [65] |

| TCAAAACCCCTATTAAAGCC | ||||

| Tetracyclines | ||||

| tetA | GCGCTNTATGCGTTGATGCA | 62 | 387 | [59] |

| ACAGCCCGTCAGGAAATT | ||||

| tetB | TACGTGAATTTATTGCTTCGG | 60 | 206 | [66] |

| ATACAGCATCCAAAGCGCAC | ||||

| tetM | TCAGTGGGAAAATACGAAGGTG | 56 | 140 | [59] |

| GAGTTTGTGCTTGTACGCCATC | ||||

| tetO | ACGGARAGTTTATTGTATACC | 56 | 171 | [59] |

| TGGCGTATCTATAATGTTGAC | ||||

| tetQ | AGAATCTGCTGTTTGCCAGTG | 56 | 169 | [59] |

| CGGAGTGTCAATGATATTGCA | ||||

| tetS | GAAAGCTTACTATACAGTAGC | 56 | 170 | [59] |

| AGGAGTATCTACAATATTTAC | ||||

| tetW | GAGAGCCTGCTATATGCCAGC | 56 | 168 | [59] |

| GGGCGTATCCACAATGTTAAC | ||||

| tetX | AGCCTTACCAATGGGTGTAAA | 56 | 280 | [59] |

| TTCTTACCTTGGACATCCCG | ||||

| Chloramphenicol | ||||

| floR | CGCCGTCATTCCTCACCTTC | 50 | 215 | [67] |

| GATCACGGGCCACGCTGTGTC | ||||

| cmlA | GCCAGCAGTGCCGTTTAT | 55 | 158 | [68] |

| GGCCACCTCCCAGTAGAA | ||||

| catI | GGTGATATGGGATAGTGTT | 52 | 348 | [53] |

| CCATCACATACTGCATGATG | ||||

| catII | GATTGACCTGAATACCTGGAA | 54 | 567 | [53] |

| CCATCACATACTGCATGATG | ||||

| catIII | CCATACTCATCCGATATTGA | 52 | 275 | [53] |

| CCATCACATACTGCATGATG | ||||

| catIV | CCGGTAAAGCGAAATTGTAT | 54 | 451 | [53] |

| CCATCACATACTGCATGATG |

Table A3.

Experimental antimicrobial selection and antimicrobial break point.

Table A3.

Experimental antimicrobial selection and antimicrobial break point.

| Classes of Antimicrobials | Antimicrobials | Concentration of Solution (μg/mL) | MIC of Vc (μg/mL) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Susceptible | Intermediate | Resistant | ||||

| β-lactams | Penicillins | Ampicillin (AMP) | 5120 | ≤8 | 16 | ≥32 |

| Carbapenems | Meropenem (MEM) | 5120 | ≤1 | 2 | ≥4 | |

| Imipenem (IPM) | 10240 | ≤1 | 2 | ≥4 | ||

| 1st-Generation Cephalosporins | Cefazolin (CZO) | 5120 | ≤2 | 4 | ≥8 | |

| 2nd-Generation Cephalosporins | Cefoxitin (FOX) | 5120 | ≤8 | 16 | ≥32 | |

| 3rd-Generation Cephalosporins | Cefotaxime (CTX) | 5120 | ≤1 | 2 | ≥4 | |

| 4th-Generation Cephalosporins | Cefepime (FEP) | 5120 | ≤2 | 4-8 | ≥16 | |

| Tetracyclines | Tetracycline (TET) | 5120 | ≤4 | 8 | ≥16 | |

| Doxycycline (DOX) | 5120 | ≤4 | 8 | ≥16 | ||

| Chloramphenicol | Chloromycetin (CHL) | 5120 | ≤8 | 16 | ≥32 | |

| Sulfonamides | Sulfamethoxazole (SMX) | 4864 | ≤38 | - | ≥76 | |

| Cotrimoxazole (SXT) | 4864/256 | 38/2 | - | 76/4 | ||

| Macrolides | Erythromycin (ERY) | 5120 | ≤0.5 | 1-4 | ≥8 | |

| Azithromycin (AZM) | 5120 | ≤2 | 4 | ≥8 | ||

| Aminoglycoside | Gentamycin (GEN) | 5120 | ≤4 | 8 | ≥16 | |

| Kanamycin (KAN) | 5120 | ≤16 | 32 | ≥64 | ||

| Nitrofurans | Nitrofurantoin (NIT) | 5120 | ≤32 | 64 | ≥128 | |

References

- El-Zamkan, M.A.; Ahmed, A.S.; Abdelhafeez, H.H.; Mohamed, H.M.A. Molecular characterization of Vibrio species isolated from dairy and water samples. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 15368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert-Pillot, A.; Copin, S.; Himber, C.; Gay, M.; Quilici, M.-L. Occurrence of the three major Vibrio species pathogenic for human in seafood products consumed in France using real-time PCR. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2014, 189, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Kessel, J.C.; Camilli, A. Vibrio cholerae: A fundamental model system for bacterial genetics and pathogenesis research. J. Bacteriol. 2024, 206, e0024824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemens, J.D.; Nair, G.B.; Ahmed, T.; Qadri, F.; Holmgren, J. Cholera. Lancet 2017, 390, 1539–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandal, S.; Mandal, M.D.; Pal, N.K. Cholera: A great global concern. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2011, 4, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Wu, J.; Chen, L. Virulence, antimicrobial and heavy metal tolerance, and genetic diversity of Vibrio cholerae recovered from commonly consumed freshwater fish. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 27338–27352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valarikova, J.; Korcova, J.; Ziburova, J.; Rosinsky, J.; Cizova, A.; Bielikova, S.; Sojka, M.; Farkas, P. Potential pathogenicity and antimicrobial resistance of aquatic Vibrio isolates from freshwater in Slovakia. Folia Microbiol. 2020, 65, 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Miao, Z.; Li, X.; Chen, N.; Gu, W.; Liu, X.; Yang, H.; Wei, W.; Zhang, X. Pathogenicity of non-O1/O139 Vibrio cholerae and its induced immune response in Macrobrachium rosenbergii. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019, 92, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dua, P.; Karmakar, A.; Ghosh, C. Virulence gene profiles, biofilm formation, and antimicrobial resistance of Vibrio cholerae non-O1/non-O139 bacteria isolated from West Bengal, India. Heliyon 2018, 4, e01040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gugliandolo, C.; Carbone, M.; Fera, M.T.; Irrera, G.P.; Maugeri, T.L. Occurrence of potentially pathogenic vibrios in the marine environment of the Straits of Messina (Italy). Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2005, 50, 692–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Flaherty, E.; Cummins, E. antimicrobial resistance in surface water ecosystems: Presence in the aquatic environment, prevention strategies, and risk assessment. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. 2017, 23, 299–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capkin, E.; Terzi, E.; Altinok, I. Occurrence of antimicrobial resistance genes in culturable bacteria isolated from Turkish trout farms and their local aquatic environment. Dis. Aquat. Org. 2015, 114, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Ye, F.; Qu, J.; Dai, Z. Insight into the antimicrobial Resistance of Bacteria Isolated from Popular Aquatic Products Collected in Zhejiang, China. Pol. J. Microbiol. 2023, 72, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wu, Q.; Xu, H.; Pan, Y.; Malakar, P.K.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Z. Change of antimicrobial resistance in Vibrio spp. during shrimp culture in Shanghai. Aquaculture 2024, 580, 740303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karen Alvarez-Contreras, A.; Irma Quinones-Ramirez, E.; Vazquez-Salinas, C. Prevalence, detection of virulence genes and antimicrobial susceptibility of pathogen Vibrio species isolated from different types of seafood samples at "La Nueva Viga" market in Mexico City. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek Int. J. Gen. Mol. Microbiol. 2021, 114, 1417–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wali, K.B.; Essiet, U.U.; Ajayi, A.; Akintunde, G.; Olukoya, D.K.; Adeleye, A.I.; Smith, S.I. Molecular diversity and antimicrobial susceptibility profile of Vibrio species and distribution of other bacteria isolated from water Hyacinth (Eichornia crassipes) and Lagos lagoon. Biologia 2024, 79, 2189–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abowei, J.F.N. Salinity, dissolved oxygen, pH and surface water temperature conditions in Nkoro River, Niger Delta, Nigeria. Adv. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 2, 36–40. [Google Scholar]

- SN/T 1022-2010; Detection of Vibrio Cholerae in Food for Import and Export. General Administration of Quality Supervision: Beijing, China, 2010.

- Fu, H.; Yu, P.; Liang, W.; Kan, B.; Peng, X.; Chen, L. Virulence, Resistance, and Genomic Fingerprint Traits of Vibrio cholerae Isolated from 12 Species of Aquatic Products in Shanghai, China. Microb. Drug Resist. 2020, 26, 1526–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Titilawo, Y.; Sibanda, T.; Obi, L.; Okoh, A. Multiple antimicrobial resistance indexing of Escherichia coli to identify high-risk sources of faecal contamination of water. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 10969–10980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejdi, S.; Emira, N.; Ali, M.; Hafedh, H.; Amina, B. Biochemical characteristics and genetic diversity of Vibrio spp. and Aeromonas hydrophila strains isolated from the Lac of Bizerte (Tunisia). World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 26, 2037–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padovan, A.; Siboni, N.; Kaestli, M.; King, W.L.; Seymour, J.R.; Gibb, K. Occurrence and dynamics of potentially pathogenic vibrios in the wet-dry tropics of northern Australia. Mar. Environ. Res. 2021, 169, 105405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, E.d.G.d.R.; Lopes, M.J.S.; Oliveira, E.G.d.; Hofer, E. Associação de Vibrio cholerae com o zooplâncton de águas estuárias da Baía de São Marcos/São Luis—MA, Brasil. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2004, 37, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, A.; Bordalo, A.A. Detection and Quantification of Vibrio cholerae, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, and Vibrio vulnificus in Coastal Waters of Guinea-Bissau (West Africa). Ecohealth 2016, 13, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batabyal, P.; Mookerjee, S.; Einsporn, M.H.; Lara, R.J.; Palit, A. Environmental drivers on seasonal abundance of riverine-estuarine V. cholerae in the Indian Sundarban mangrove. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 69, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, T.J.; Neigel, J.E. Effects of temperature and salinity on prevalence and intensity of infection of blue crabs, Callinectes sapidus, by Vibrio cholerae, V. parahaemolyticus, and V. vulnificus in Louisiana. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2018, 151, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, H.A.; El Bayomi, R.M.; Hussein, M.A.; Khedr, M.H.E.; Remela, E.M.A.; El-Ashram, A.M.M. Molecular characterization, antimicrobial resistance pattern and biofilm formation of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and V-cholerae isolated from crustaceans and humans. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2018, 274, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, B.B.; Samal, D.; Nayak, S.R.; Pany, S. Spectrum of ctxB genotypes, antibiogram profiles and virulence genes of Vibrio cholerae serogroups isolated from environmental water sources from Odisha, India. BMC Microbiol. 2023, 23, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Igere, B.E.; Okoh, A.I.; Nwodo, U.U. Atypical and dual biotypes variant of virulent SA-NAG-Vibrio cholerae: An evidence of emerging/evolving patho-significant strain in municipal domestic water sources. Ann. Microbiol. 2022, 72, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zago, V.; Zambon, M.; Civettini, M.; Zaltum, O.; Manfrin, A. Virulence-associated factors in Vibrio cholerae non-O1/non-O139 and V. mimicus strains isolated in ornamental fish species. J. Fish Dis. 2017, 40, 1857–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wu, Y.; Sun, X.; Ma, J.; Li, X.; Liu, C.; Xie, H. Non-O1/non-O139 Vibrio cholerae bacteraemia in mainland China from 2005 to 2019: Clinical, epidemiological and genetic characteristics. Epidemiol. Infect. 2020, 148, e186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hageman, S.J. Regulation of Hemagglutinin/Protease (HAP) in Classical and El Tor Biotype Vibrio cholerae Strains; California State University: Fresno, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kislichkina, A.A.; Stepanshina, V.N.; Nizova, A.V.; Maiskaia, N.V.; Mukhina, T.N.; Mironova, R.I.; Shemiakin, I.G. Vibrio cholerae strains certification. Zhurnal Mikrobiol. Epidemiol. Immunobiol. 2012, 6, 22–26. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, N.; Stephan, R.; Cernela, N.; Horlbog, J.A.; Biggel, M. Genomic characteristics of clinical non-toxigenic Vibrio cholerae isolates in Switzerland: A cross-sectional study. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2024, 154, 3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, K.H.; Ng, T.K.; Yuen, K.Y.; Yam, W.C. Detection of RTX toxin gene in Vibrio cholerae by PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2001, 39, 2594–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goel, A.K.; Jiang, S.C. Genetic determinants of virulence, antibiogram and altered biotype among the Vibrio cholerae O1 isolates from different cholera outbreaks in India. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2010, 10, 815–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abioye, O.E.; Nontongana, N.; Osunla, C.A.; Okoh, A.I. antimicrobial resistance and virulence genes profiling of Vibrio cholerae and Vibrio mimicus isolates from some seafood collected at the aquatic environment and wet markets in Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0290356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottaviani, D.; Medici, L.; Talevi, G.; Napoleoni, M.; Serratore, P.; Zavatta, E.; Bignami, G.; Masini, L.; Chierichetti, S.; Fisichella, S.; et al. Molecular characterization and drug susceptibility of non-O1/O139 V. cholerae strains of seafood, environmental and clinical origin, Italy. Food Microbiol. 2018, 72, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nur, A.H.; Ceccarelli, D.; Grim, C.J.; Taviani, E.; Jina, C.; Abdus, S.; Munirul, A.; Abul, K.S.; Sack, R.B.; Anwar, H.; et al. Distribution of virulence genes in clinical and environmental Vibrio cholerae strains in Bangladesh. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 5782–5785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asmaa, B.M.B.T.; Abou Elez, R.M.M.; Ibrahim, E.; Samah, S.A.; Hend, S.N.; Eman, N.A. Genotypic characterization and antimicrobial resistance of Vibrio cholerae and Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated from milk, dairy products, and humans with respect to inhibitory activity of a probiotic Lactobacillus rhamenosus. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 150, 111930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiavelli, D.A.; Marsh, J.W.; Taylor, R.K. The mannose-sensitive hemagglutinin of Vibrio cholerae promotes adherence to zooplankton. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001, 67, 3220–3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayan, M.; Rima, T.; Sekhar Chatterjee, N.; Amit, G.; Ritam, S.; Hemanta, K.; Rani Saha, D.; Manoj, K.C.; Nyunt Wai, S.; Amit, P. Cytotoxic and inflammatory responses induced by outer membrane vesicle-associated biologically active proteases from Vibrio cholerae. Infect. Immun. 2016, 84, 1478–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajpara, N.; Vinothkumar, K.; Mohanty, P.; Singh, A.K.; Singh, R.; Sinha, R.; Nag, D.; Koley, H.; Bhardwaj, A.K. Synergistic Effect of Various Virulence Factors Leading to High Toxicity of Environmental V. cholerae Non-O1/Non-O139 Isolates Lacking ctx Gene: Comparative Study with Clinical Strains. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e76200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tengfei, X.; Qingping, W.; Jumei, Z.; Xiaoke, X.; Jianheng, C. Comparison of Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolates from aquatic products and clinical by antimicrobial susceptibility, virulence, and molecular characterisation. Food Control 2017, 71, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qianxing, W.; Ali Zaman, V.; Nazanin, O.; Vahab Hassan, K.; Abbas, M.; Parand, K.; Ebrahim, K. Antimicrobial resistance among clinical Vibrio cholerae non-O1/non-O139 isolates: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Pathog. Glob. Health 2023, 117, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, B.; Verma, J.; Kumar, P.; Ghosh, A.; Ramamurthy, T. antimicrobial resistance in Vibrio cholerae: Understanding the ecology of resistance genes and mechanisms. Vaccine 2020, 38, A83–A92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lalumera, G.M.; Calamari, D.; Galli, P.; Castiglioni, S.; Crosa, G.; Fanelli, R. Preliminary investigation on the environmental occurrence and effects of antimicrobials used in aquaculture in Italy. Chemosphere 2004, 54, 661–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiou, J.; Li, R.; Chen, S. CARB-17 Family of β-Lactamases Mediates Intrinsic Resistance to Penicillins in Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 3593–3595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephen, J.; Lekshmi, M.; Ammini, P.; Kumar, S.H.; Varela, M.F. Membrane Efflux Pumps of Pathogenic Vibrio Species: Role in Antimicrobial Resistance and Virulence. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheney, L.; Payne, M.; Kaur, S.; Lan, R. Multilevel Genome Typing Describes Short- and Long-Term Vibrio cholerae Molecular Epidemiology. Msystems 2021, 6, e0013421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackbusch, S.; Wichels, A.; Gimenez, L.; Doepke, H.; Gerdts, G. Potentially human pathogenic Vibrio spp. in a coastal transect: Occurrence and multiple virulence factors. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 707, 136113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, Z.Z.; Farhana, I.; Tulsiani, S.M.; Beguml, A.; Jensen, P.K.M. Transmission and Toxigenic Potential of Vibrio cholerae in Hilsha Fish Tenualosa ilisha) for Human Consumption in Bangladesh. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Hu, X.; Xu, T.; Zhang, H.; Sheng, D.; Yin, D. Prevalence of antimicrobial resistance genes and their relationship with antimicrobials in the Huangpu river and the drinking water sources, Shanghai, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 458–460, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, C.W.; Zhang, W.; Sturm, B.S.M.; Graham, D.W. Differential fate of erythromycin and beta-lactam resistance genes from swine lagoon waste under different aquatic conditions. Environ. Pollut. 2010, 158, 1506–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dallenne, C.; Da Costa, A.; Decre, D.; Favier, C.; Arlet, G. Development of a set of multiplex PCR assays for the detection of genes encoding important β-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2010, 65, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneha, K.G.; Anas, A.; Jayalakshmy, K.V.; Jasmin, C.; Das, P.V.V.; Pai, S.S.; Pappu, S.; Nair, M.; Muraleedharan, K.R.; Sudheesh, K.; et al. Distribution of multiple antimicrobial resistant Vibrio spp. across Palk Bay. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2016, 3, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zago, V.; Veschetti, L.; Patuzzo, C.; Malerba, G.; Lleo, M.M. Shewanella algae and Vibrio spp. strains isolated in Italian aquaculture farms are reservoirs of antimicrobial resistant genes that might constitute a risk for human health. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 154, 111057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, R.; Kim, S.-C.; Carlson, K.H.; Pruden, A. Effect of River Landscape on the sediment concentrations of antimicrobials and corresponding antimicrobial resistance genes (ARG). Water Res. 2006, 40, 2427–2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Su, Y.; Deng, Y.; Guo, Z.; Cheng, C.; Ma, H.; Liu, G.; Xu, L.; Feng, J. Spatial and temporal variation of antimicrobial resistance in marine fish cage-culture area of Guangdong, China. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 246, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, A.H.; Raval, I.H.; Haldar, S. SXT int harboring bacteria as effective indicators to determine high-risk reservoirs of multiple antimicrobial resistance in different aquatic environments of western coast of Gujarat, India. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 113, 106143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, B.; Cui, Y.; Tian, W.; Li, J.; Xie, B.; Yin, F. Abundances and profiles of antimicrobial resistance genes as well as co-occurrences with human bacterial pathogens in ship ballast tank sediments from a shipyard in Jiangsu Province, China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 157, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H.; Raza, S.; Farooq, A.; Kim, J.; Unno, T. Fish farm effluents as a source of antimicrobial resistance gene dissemination on Jeju Island, South Korea. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 276, 116764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Dai, W.; Sun, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L. Prevalence of Plasmid-Mediated Quinolone Resistance and Aminoglycoside Resistance Determinants among Carbapeneme Non-Susceptible Enterobacter cloacae. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e47636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahanayake, P.S.; Hossain, S.; Wickramanayake, M.V.K.S.; Wimalasena, S.H.M.P.; Heo, G.J. Manila clam (Ruditapes philippinarum) marketed in Korea as a source of vibrios harbouring virulence and β-lactam resistance genes. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 71, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouoba, L.I.I.; Lei, V.; Jensen, L.B. Resistance of potential probiotic lactic acid bacteria and bifidobacteria of African and European origin to antimicrobials: Determination and transferability of the resistance genes to other bacteria. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2008, 121, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminov, R.I.; Chee-Sanford, J.C.; Garrigues, N.; Teferedegne, B.; Krapac, I.J.; White, B.A.; Mackie, R.I. Development, validation, and application of PCR primers for detection of tetracycline efflux genes of gram-negative bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 1786–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard, C.; Fairbrother, J.M.; Bekal, S.; Sanschagrin, F.; Levesque, R.C.; Brousseau, R.; Masson, L.; Larivière, S.; Harel, J. Antimicrobial resistance genes in enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli O149:K91 isolates obtained over a 23-year period from pigs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003, 47, 3214–3221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, H.; Hu, X.; Xu, Y.; Xu, W.; Huang, X.; Wen, G.; Yang, K.; Li, Z.; Cao, Y. Persistence and spatial variation of antimicrobial resistance genes and bacterial populations change in reared shrimp in South China. Environ. Int. 2018, 119, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).