Development of Spirulina-Enriched Fruit and Vegetable Juices: Nutritional Enhancement, Antioxidant Potential, and Sensory Challenges

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Juices

2.2. Basic Chemical Composition

2.3. Total Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Activity

2.4. Colour and Texture Measurements

2.5. Sensory Analysis of Juices

2.5.1. Initial Acceptability Test

2.5.2. Descriptive Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Basic Nutritional Composition, Total Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Activity

3.2. Colour and Texture Measurements

3.3. Sensory Evaluation

3.4. Generalized Procrustes Analysis (GPA) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

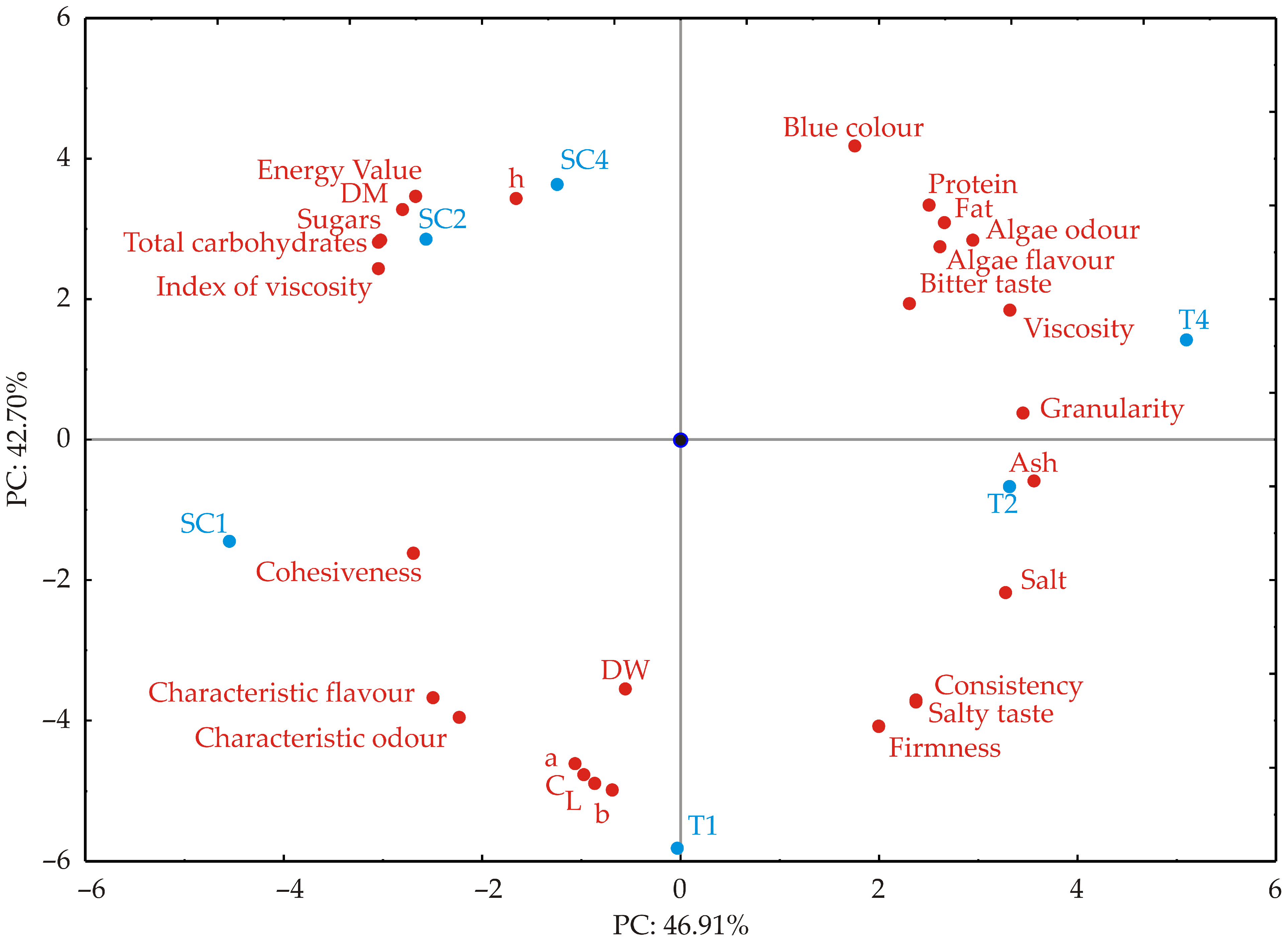

3.5. Correlation Analysis and Principal Component Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Birch, C.S.; Bonwick, G.A. Ensuring the Future of Functional Foods. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 54, 1467–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanakis, C.M. The Future of Food. Foods 2024, 13, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.T.; Lu, P.; Parrella, J.A.; Leggette, H.R. Consumer Acceptance toward Functional Foods: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cencic, A.; Chingwaru, W. The Role of Functional Foods, Nutraceuticals, and Food Supplements in Intestinal Health. Nutrients 2010, 2, 611–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajzer, Z.E.; Alibrahem, W.; Kharrat Helu, N.; Oláh, C.; Prokisch, J. Functional Foods in Clinical Trials and Future Research Directions. Foods 2025, 14, 2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Paiva, K.F.; Sousa, L.L.; Cavalcante, M.P.; Barros, S.L.; Santos, N.C.; Santos, F.A.O.; Mendes, L.G.; Cavalcante, A.R.; Sousa, M.M.; Rocha, A.P.T.; et al. Investigating the Impact of Pasteurization on the Bioactive-Rich Potential of Psyllium and Spirulina in a Concentrated Beverage. Meas. Food 2024, 13, 100129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlFadhly, N.K.Z.; Alhelfi, N.; Altemimi, A.B.; Verma, D.K.; Cacciola, F.; Narayanankutty, A. Trends and Technological Advancements in the Possible Food Applications of Spirulina and Their Health Benefits: A Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 5584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Ruiz, F.E.; Andrade-Bustamante, G.; Holguín-Peña, R.J.; Renganathan, P.; Gaysina, L.A.; Sukhanova, N.V.; Puente, E.O.R. Microalgae as Functional Food Ingredients: Nutritional Benefits, Challenges, and Regulatory Considerations for Safe Consumption. Biomass 2025, 5, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, J.; Cardoso, C.; Bandarra, N.M.; Afonso, C. Microalgae as Healthy Ingredients for Functional Food: A Review. Food Funct. 2017, 8, 2672–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prates, J.A.M. Unlocking the Functional and Nutritional Potential of Microalgae Proteins in Food Systems: A Narrative Review. Foods 2025, 14, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelekli, A.; Özbal, B.; Bozkurt, H. Challenges in Functional Food Products with the Incorporation of Some Microalgae. Foods 2024, 13, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marjanović, B.; Benković, M.; Jurina, T.; Sokač Cvetnić, T.; Valinger, D.; Gajdoš Kljusurić, J.; Jurinjak Tušek, A. Bioactive Compounds from Spirulina spp.—Nutritional Value, Extraction, and Application in Food Industry. Separations 2024, 11, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjula, R.; Vijayavahini, R.; Lakshmi, T.S. Formulation and Quality Evaluation of Spirulina Incorporated Ready to Serve (RTS) Functional Beverage. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. Arts Sci. Commer. 2021, 1, 29–35. Available online: https://www.sdnbvc.edu.in/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/PAPER-ID-4.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Nunes, M.C.; Fernandes, I.; Vasco, I.; Sousa, I.; Raymundo, A. Tetraselmis chuii as a Sustainable and Healthy Ingredient to Produce Gluten-Free Bread: Impact on Structure, Colour and Bioactivity. Foods 2020, 9, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stunda-Zujeva, A.; Makarova, E.; Borisova, A.; Volodina, O.; Fomina, T.; Stegane, S. Comparison of antioxidant activity in various spirulina containing products and factors affecting it. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeunović, J.B.; Marković, S.B.; Kovač, D.J.; Mišan, A.Č.; Mandić, A.I.; Svirčev, Z.B. Filamentozne cijanobakterije poreklom sa područja Vojvodine kao izvor fikobilinskih pigmenata kao potencijalnih prirodnih koloranata. Food Feed. Res. 2012, 39, 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Wajda, Ł.; Duda-Chodak, A.; Tarko, T.; Izajasza-Parchańska, M. The impact of “Spirulina” on the microbiological stability of unpasteurised apple juice. In Bezpečnosť a Kontrola Potravín. Zborník Prác z XII. Medzinárodnej Vedeckej Konferencie, Smolenice; Slovenská Poľnohospodárska Univerzita: Nitra, Slovakia, 2015; pp. 77–80. Available online: http://www.slpk.sk/eldo/2015/zborniky/9788055213149/02-mikrobiologicka/Wajda.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Mahmoud, S.H.; Mahmoud, R.M.; Ashoush, I.S.; Attia, M.Y. Immunomodulatory and Antioxidant Activity of Pomegranate Juice Incorporated with Spirulina and Echinacea Extracts Sweetened by Stevioside. J. Agric. Vet. Sci. Qassim Univ. 2015, 8, 161–174. Available online: https://platform.almanhal.com/Reader/Article/93209 (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Deffairi, D.; Kouidri, A.; Alili, D.; Bougherra, F.; Abdellaoui, Z.; Hadjadj, N.; Akkal, S. Effect of the Incorporation of Spirulina on the Physicochemical Parameters of a Grape Juice. J. EcoAgriTourism 2022, 18, 67–75. Available online: https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/pdf/10.5555/20220299930 (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Aljobair, M.O.; Albaridi, N.A.; Alkuraieef, A.N.; AlKehayez, N.M. Physicochemical Properties, Nutritional Value, and Sensory Attributes of a Nectar Developed Using Date Palm Puree and Spirulina. Int. J. Food Prop. 2021, 24, 845–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okur, İ.; Baltacıoğlu, C.; Ağçam, E.; Baltacıoğlu, H.; Alpas, H. Evaluation of the effect of different extraction techniques on sour cherry pomace phenolic content and antioxidant activity and determination of phenolic compounds by FTIR and HPLC. Waste Biomass Valorization 2019, 10, 3545–3555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, D.; Gürel, D.B.; Çağındı, Ö.; Kayaardı, S. Heat Treatment and Microwave Applications on Homemade Sour Cherry Juice: The Effect on Anthocyanin Content and Some Physicochemical Properties. Curr. Plant Biol. 2022, 29, 100242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International, 17th ed.; AOAC International: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- AACC. Approved Methods of the American Association of Cereal Chemists, 10th ed.; American Association of Cereal Chemists: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2000; Method 80-68. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 6869:2008; Animal Feeding Stuffs—Determination of Calcium, Copper, Iron, Magnesium, Manganese, Potassium, Sodium and Zinc—Method Using Atomic Absorption Spectrometry. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008.

- Singleton, V.L.; Orthofer, R.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. Analysis of Total Phenols and Other Oxidation Substrates and Antioxidants by Means of Folin–Ciocalteu Reagent. In Methods in Enzymology; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1999; Volume 299, pp. 152–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler-Rivas, C.; Espín, J.C.; Wichers, H.J. An Easy and Fast Test to Compare Total Free Radical Scavenger Capacity of Foodstuffs. Phytochem. Anal. 2000, 11, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzie, I.F.; Strain, J.J. Ferric Reducing/Antioxidant Power Assay: Direct Measure of Total Antioxidant Activity of Biological Fluids and Modified Version for Simultaneous Measurement of Total Antioxidant Power and Ascorbic Acid Concentration. In Methods in Enzymology; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1999; Volume 299, pp. 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 8589:2007; Sensory Analysis—General Guidance for the Design of Test Rooms. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007.

- Vallverdú-Queralt, A.; Bendini, A.; Tesini, F.; Valli, E.; Lamuela-Raventos, R.M.; Toschi, T.G. Chemical and Sensory Analysis of Commercial Tomato Juices Present on the Italian and Spanish Markets. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 1044–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Rune, C.J.B.; Thybo, A.K.; Clausen, M.P.; Orlien, V.; Giacalone, D. Sensory Quality and Consumer Perception of High Pressure Processed Orange Juice and Apple Juice. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 173, 114303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meilgaard, M.C.; Carr, B.T.; Civille, G.V. Sensory Evaluation Techniques, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwan, J.A. Preference Mapping for Product Optimization. In Multivariate Analysis of Data in Sensory Science; Naes, T., Risvik, E., Eds.; Elsevier Applied Science: London, UK, 1996; pp. 71–102. [Google Scholar]

- TIBCO Software Inc. TIBCO Data Science. 2020. Available online: https://www.tibco.com/products/data-science (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Park, W.S.; Kim, H.-J.; Li, M.; Lim, D.H.; Kim, J.; Kwak, S.-S.; Kang, C.-M.; Ferruzzi, M.G.; Ahn, M.-J. Two Classes of Pigments, Carotenoids and C-Phycocyanin, in Spirulina Powder and Their Antioxidant Activities. Molecules 2018, 23, 2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahlol, H.E.M. Utilization of Spirulina Algae to Improve the Nutritional Value of Kiwifruits and Cantaloupe Nectar Blends. Ann. Agric. Sci. Moshtohor 2018, 56 (4th ICBAA), 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanzadeh, H.; Ghanbarzadeh, B.; Galali, Y.; Bagheri, H. The Physicochemical Properties of the Spirulina-Wheat Germ-Enriched High-Protein Functional Beverage Based on Pear-Cantaloupe Juice. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 10, 3651–3661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidor, E.; Trybulec, K.; Tomczyk, M.; Dzugan, M. Spirulina (Arthrospira platensis) jako Składnik Napojów Funkcjonalnych. Żywność Nauka Technol. Jakość 2023, 30, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonin, F.S.; Steimbach, L.M.; Wiens, A.; Perlin, C.M.; Pontarolo, R. Impact of Natural Juice Consumption on Plasma Antioxidant Status: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Molecules 2015, 20, 22146–22156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, S.S.; Cutler, D.; Ding, M.; Vallyathan, V.; Castranova, V.; Shi, X. Antioxidant properties of fruit and vegetable juices: More to the story than ascorbic acid. Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2002, 32, 193–200. [Google Scholar]

- Šeregelj, V.; Tumbas Šaponjac, V.; Pezo, L.; Kojić, J.; Cvetković, B.; Ilić, N. Analysis of antioxidant potential of fruit and vegetable juices available in Serbian markets. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2024, 30, 456–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fradique, M.; Batista, A.P.; Nunes, M.C.; Gouveia, L.; Bandarra, N.M.; Raymundo, A. Incorporation of Chlorella vulgaris and Spirulina maxima Biomass in Pasta Products. Part 1: Preparation and Evaluation. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2010, 90, 1656–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beresovsky, N.; Kopelman, I.J.; Mizrahi, S. The Role of Pulp Interparticle Interaction in Determining Tomato Juice Viscosity. J. Food Process. Preserv. 1995, 19, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moelants, K.R.N.; Cardinaels, R.; Jolie, R.P.; Van Buggenhout, S.; Van Loey, A.M.; Moldenaers, P.; Hendrickx, M.E. Rheology of Concentrated Tomato-Derived Suspensions: Effects of Particle Characteristics. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2014, 7, 248–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiziani, S.; Vodovotz, Y. Rheological Effects of Soy Protein Addition to Tomato Juice. Food Hydrocoll. 2005, 19, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolić, I.; Lončarević, I.; Rakita, S.; Čabarkapa, I.; Vulić, J.; Takači, A.; Petrović, J. Technological Challenges of Spirulina Powder as the Functional Ingredient in Gluten-Free Rice Crackers. Processes 2025, 13, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guil-Guerrero, J.L.; Prates, J.A.M. Microalgae Bioactives for Functional Food Innovation and Health Promotion. Foods 2025, 14, 2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delompré, T.; Guichard, E.; Briand, L.; Salles, C. Taste Perception of Nutrients Found in Nutritional Supplements: A Review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gower, J.C. Generalized Procrustes Analysis. Psychometrika 1975, 40, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langsrud, Ø. Rotation Tests. Stat. Comput. 2005, 15, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyners, M.; Castura, J.C.; Carr, B.T. Existing and New Approaches for the Analysis of CATA Data. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 30, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhoff, K.; MacFie, H.J.H. Preference Mapping in Practice. In Measurement of Food Preferences; MacFie, H.J.H., Thomson, D.M.H., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1994; pp. 137–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltier, C.; Visalli, M.; Schlich, P. Comparison of Canonical Variate Analysis and Principal Component Analysis for Evaluating Product Discrimination by a Trained Panel. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 40, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, A.P.; Niccolai, A.; Bursic, I.; Sousa, I.; Raymundo, A.; Rodolfi, L.; Biondi, N.; Tredici, M.R. Microalgae as Functional Ingredients in Savory Food Products: Application to Wheat Crackers. Foods 2019, 8, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paniagua, C.; Posé, S.; Morris, V.J.; Kirby, A.R.; Quesada, M.A.; Mercado, J.A. Fruit Softening and Pectin Disassembly: An Overview of Nanostructural Pectin Modifications Assessed by Atomic Force Microscopy. Ann. Bot. 2014, 114, 1375–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wold, S.; Esbensen, K.; Geladi, P. Principal Component Analysis. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 1987, 2, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granato, D.; Santos, J.S.; Escher, G.B.; Ferreira, B.L.; Maggio, R.M. Use of Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA) for Multivariate Association between Bioactive Compounds and Functional Properties in Foods: A Critical Perspective. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 72, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | SC1 | SC2 | SC4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dry matter (g/100 g) | 15.21 ± 0.06 b | 15.81 ± 0.13 a | 15.97 ± 0.21 a |

| Ash (g/100 g) | 0.90 ± 0.01 c | 1.01 ± 0.03 b | 1.13 ± 0.03 a |

| Protein (g/100 g) | 0.80 ± 0.03 c | 1.08 ± 0.03 b | 1.36 ± 0.03 a |

| Fat (g/100 g) | 0.05 ± 0.01 c | 0.13 ± 0.01 b | 0.21 ± 0.01 a |

| Total carbohydrates (g/100 g) | 13.47 ± 0.04 a | 13.59 ± 0.14 a | 13.27 ± 0.23 a |

| Total sugars (g/100 g) | 11.25 ± 0.05 b | 11.30 ± 0.04 ab | 11.38 ± 0.03 a |

| Salt (g/100 g) | 0.05 ± 0.00 c | 0.10 ± 0.00 b | 0.15 ± 0.00 a |

| Energy value (kJ/100 g) | 259.27 ± 1.77 b | 273.20 ± 3.21 a | 279.48 ± 4.65 a |

| TPC (mg GAE/g d.w.) | 12.82 ± 0.30 a | 12.88 ± 0.99 a | 13.04 ± 1.74 a |

| DPPH IC50 (mg/mL) | 260.19 ± 35.49 a | 177.95 ± 46.97 b | 134.79 ± 10.45 b |

| FRAP (mg AAE/g d.w.) | 0.76 ± 0.08 a | 0.99 ± 0.19 a | 1.08 ± 0.27 a |

| Parameter | T1 | T2 | T4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dry matter (g/100 g) | 8.45 ± 0.06 c | 9.09 ± 0.13 b | 9.73 ± 0.21 a |

| Ash (g/100 g) | 1.27 ± 0.01 c | 1.37 ± 0.02 b | 1.49 ± 0.01 a |

| Protein (g/100 g) | 0.89 ± 0.03 c | 1.17 ± 0.02 b | 1.52 ± 0.03 a |

| Fat (g/100 g) | 0.09 ± 0.01 c | 0.17 ± 0.02 b | 0.25 ± 0.01 a |

| Total carbohydrates (g/100 g) | 6.21 ± 0.11 a | 6.40 ± 0.15 a | 6.47 ± 0.27 a |

| Total sugars (g/100 g) | 4.07 ± 0.01 a | 4.24 ± 0.10 a | 4.39 ± 0.16 a |

| Salt (g/100 g) | 1.04 ± 0.01 c | 1.15 ± 0.01 b | 1.27 ± 0.01 a |

| Energy value (kJ/100 g) | 139.95 ± 0.52 c | 154.63 ± 2.95 b | 170.48 ± 3.28 a |

| TPC (mg GAE/g d.w.) | 7.08 ± 0.41 a | 7.00 ± 0.19 a | 7.06 ± 0.22 a |

| DPPH IC50 (mg/mL) | 267.97 ± 49.27 a | 255.70 ± 32.24 a | 171.09 ± 12.63 b |

| FRAP (mg AAE/g d.w.) | 0.05 ± 0.00 c | 0.42 ± 0.11 b | 1.27 ± 0.23 a |

| Parameter | SC1 | SC2 | SC4 | T1 | T2 | T4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIE L* | 24.54 ± 0.01 a | 20.97 ± 0.01 b | 20.60 ± 0.00 b | 29.29 ± 0.01 a | 21.94 ± 1.05 b | 20.64 ± 0.01 c |

| CIE a* | 15.21 ± 0.07 a | 3.98 ± 0.03 b | 3.65 ± 0.02 b | 16.63 ± 0.05 a | 6.09 ± 0.89 b | 6.79 ± 0.07 b |

| CIE b* | 7.24 ± 0.01 a | −0.21 ± 0.03 b | −1.86 ± 0.01 b | 15.25 ± 0.01 a | 1.84 ± 0.18 b | 0.68 ± 0.02 c |

| CIE C* | 16.85 ± 0.06 a | 3.99 ± 0.03 c | 4.10 ± 0.02 b | 22.57 ± 0.04 a | 6.36 ± 0.90 b | 6.82 ± 0.07 b |

| CIE h° | 25.45 ± 0.13 c | 357.0 ± 0.3 a | 332.9 ± 0.3 b | 42.52 ± 0.08 a | 16.97 ± 0.93 b | 5.71 ± 0.19 c |

| Firmness (g) | 16.59 ± 1.28 a | 15.20 ± 0.14 a | 15.97 ± 0.69 a | 33.44 ± 0.93 a | 24.90 ± 1.29 b | 24.60 ± 1.21 b |

| Consistency (g s) | 279.1 ± 2.3 b | 277.8 ± 1.5 b | 286.2 ± 4.5 a | 529.6 ± 5.0 a | 428.9 ± 9.5 b | 439.1 ± 3.5 b |

| Cohesive-ness (g) | −13.85 ± 0.11 b | −14.25 ± 0.14 a | −14.19 ± 0.15 a | −12.82 ± 0.20 b | −16.33 ± 1.17 a | −17.55 ± 1.23 a |

| Index of viscosity (g s) | −1.30 ± 0.05 a | −1.31 ± 0.04 a | −1.32 ± 0.05 a | −7.44 ± 1.04 b | −7.43 ± 1.26 b | −10.06 ± 1.22 a |

| Descriptor | SC1 | SC2 | SC4 | T1 | T2 | T4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blue colour intensity | 0.3 ± 0.8 b | 99.7 ± 0.8 a | 99.3 ± 1.6 a | 0.0 ± 0.0 b | 99.7 ± 0.8 a | 99.3 ± 1.6 a |

| Turbidity | 98.0 ± 3.3 a | 99.7 ± 0.8 a | 99.7 ± 0.8 a | 98.8 ± 2.0 a | 99.8 ± 0.4 a | 99.8 ± 4.0 a |

| Viscosity | 44.3 ± 6.0 b | 52.8 ± 7.1 ab | 60.5 ± 15.6 a | 50.8 ± 3.4 c | 67.0 ± 8.3 b | 80.5 ± 8.3 a |

| Granularity | 12.8 ± 4.9 a | 14.0 ± 10.8 a | 16.5 ± 16.7 a | 18.2 ± 6.7 b | 27.7 ± 14.1 ab | 39.0 ± 10.5 a |

| Characteristic odour | 97.2 ± 4.5 a | 46.0 ± 25.0 b | 46.0 ± 21.5 b | 100.0 ± 0.0 a | 39.0 ± 8.9 b | 30.7 ± 13.7 b |

| Algae odour | 0.5 ± 1.2 b | 18.0 ± 19.3 ab | 28.7 ± 22.2 a | 0.5 ± 1.2 b | 41.0 ± 15.6 a | 48.2 ± 24.4 a |

| Characteristic flavour | 99.5 ± 1.2 a | 70.8 ± 26.2 b | 64.2 ± 23.8 b | 99.2 ± 2.0 a | 59.5 ± 18.7 b | 54.2 ± 23.5 b |

| Algae flavour | 0.2 ± 0.4 b | 7.7 ± 8.3 b | 22.5 ± 15.7 a | 1.0 ± 1.5 c | 13.0 ± 5.0 b | 43.0 ± 15.3 a |

| Sweet taste | 17.0 ± 11.2 a | 14.2 ± 10.4 a | 14.7 ± 8.2 a | 22.7 ± 10.7 a | 18.0 ± 5.9 a | 14.7 ± 5.8 a |

| Salty taste | 1.5 ± 2.5 a | 0.5 ± 0.8 a | 1.2 ± 2.9 a | 64.2 ± 17.8 a | 48.5 ± 14.4 ab | 36.3 ± 10.5 b |

| Sour taste | 64.3 ± 25.1 a | 69.5 ± 30.9 a | 72.2 ± 35.3 a | 50.5 ± 20.5 b | 68.7 ± 16.2 ab | 74.8 ± 20.3 a |

| Bitter taste | 0.0 ± 0.0 a | 0.0 ± 0.0 a | 0.5 ± 1.2 a | 0.0 ± 0.0 b | 0.0 ± 0.0 b | 1.5 ± 1.8 a |

| Factors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptors | F | p | F | p |

| Source | Products | Assessors | ||

| Blue colour | 24,663.069 | <0.0001 | 0.172 | 0.970 |

| Turbidity | 1.086 | 0.392 | 4.951 | 0.003 |

| Viscosity | 26.235 | <0.0001 | 7.307 | 0.000 |

| Granularity | 12.022 | <0.0001 | 10.143 | <0.0001 |

| Characteristic odour | 32.641 | <0.0001 | 2.998 | 0.030 |

| Algae odour | 13.328 | <0.0001 | 4.352 | 0.005 |

| Mould odour | 1.000 | 0.438 | 2.500 | 0.057 |

| Characteristic flavour | 12.692 | <0.0001 | 6.468 | 0.001 |

| Algae flavour | 16.183 | <0.0001 | 0.932 | 0.477 |

| Mould flavour | 1.000 | 0.438 | 24.391 | <0.0001 |

| Sweet taste | 1.438 | 0.245 | 6.176 | 0.001 |

| Salty taste | 65.940 | <0.0001 | 4.088 | 0.008 |

| Sour taste | 2.038 | 0.108 | 12.729 | <0.0001 |

| Bitter taste | 2.946 | 0.032 | 1.161 | 0.356 |

| Products | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessors | T1 | T2 | T4 | SC1 | SC2 | SC4 |

| A1 | 6.481 | 12.729 | 12.248 | 2.836 | 18.390 | 17.255 |

| A2 | 8.984 | 14.227 | 13.593 | 2.843 | 7.658 | 9.956 |

| A3 | 2.195 | 5.551 | 15.263 | 2.466 | 10.195 | 10.955 |

| A4 | 2.749 | 6.449 | 9.824 | 3.627 | 9.145 | 11.767 |

| A5 | 7.285 | 7.965 | 13.693 | 3.074 | 16.772 | 20.791 |

| A6 | 4.914 | 12.311 | 13.511 | 2.270 | 14.217 | 13.762 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cvetković, B.; Belović, M.; Pezo, L.; Lazarević, J.; Radivojević, G.; Penić, M.; Šimurina, O.; Bajić, A. Development of Spirulina-Enriched Fruit and Vegetable Juices: Nutritional Enhancement, Antioxidant Potential, and Sensory Challenges. Foods 2025, 14, 3539. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14203539

Cvetković B, Belović M, Pezo L, Lazarević J, Radivojević G, Penić M, Šimurina O, Bajić A. Development of Spirulina-Enriched Fruit and Vegetable Juices: Nutritional Enhancement, Antioxidant Potential, and Sensory Challenges. Foods. 2025; 14(20):3539. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14203539

Chicago/Turabian StyleCvetković, Biljana, Miona Belović, Lato Pezo, Jasmina Lazarević, Goran Radivojević, Mirjana Penić, Olivera Šimurina, and Aleksandra Bajić. 2025. "Development of Spirulina-Enriched Fruit and Vegetable Juices: Nutritional Enhancement, Antioxidant Potential, and Sensory Challenges" Foods 14, no. 20: 3539. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14203539

APA StyleCvetković, B., Belović, M., Pezo, L., Lazarević, J., Radivojević, G., Penić, M., Šimurina, O., & Bajić, A. (2025). Development of Spirulina-Enriched Fruit and Vegetable Juices: Nutritional Enhancement, Antioxidant Potential, and Sensory Challenges. Foods, 14(20), 3539. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14203539