Assessing Consumer Valuation of Sustainability Certification in Seafood Products: Insight from a Discrete Choice Experiment of Korean Blue Food Market

Abstract

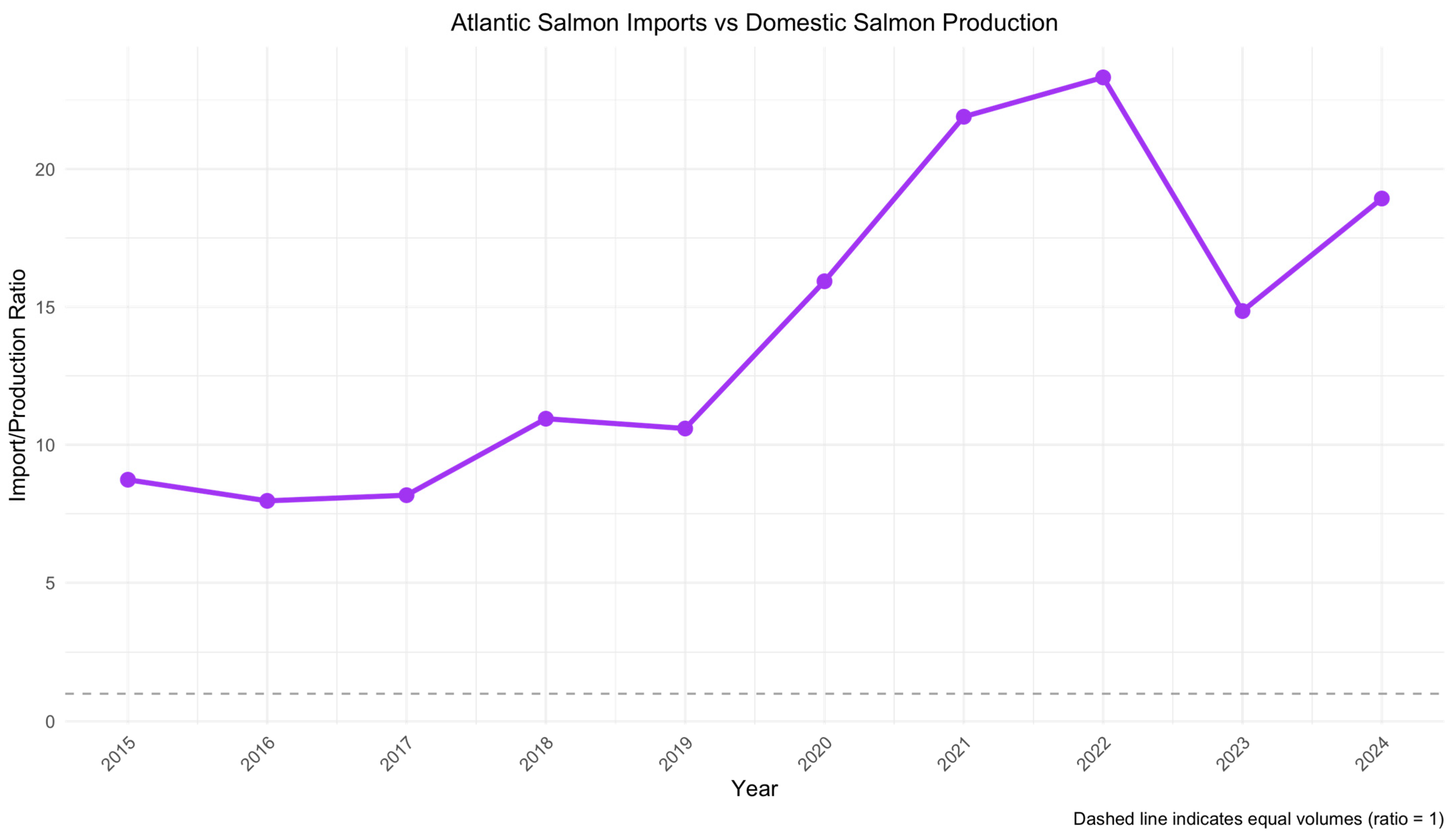

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Survey Design and Implementation

2.2. Discrete Choice Experiment Framework

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Sample Characteristics

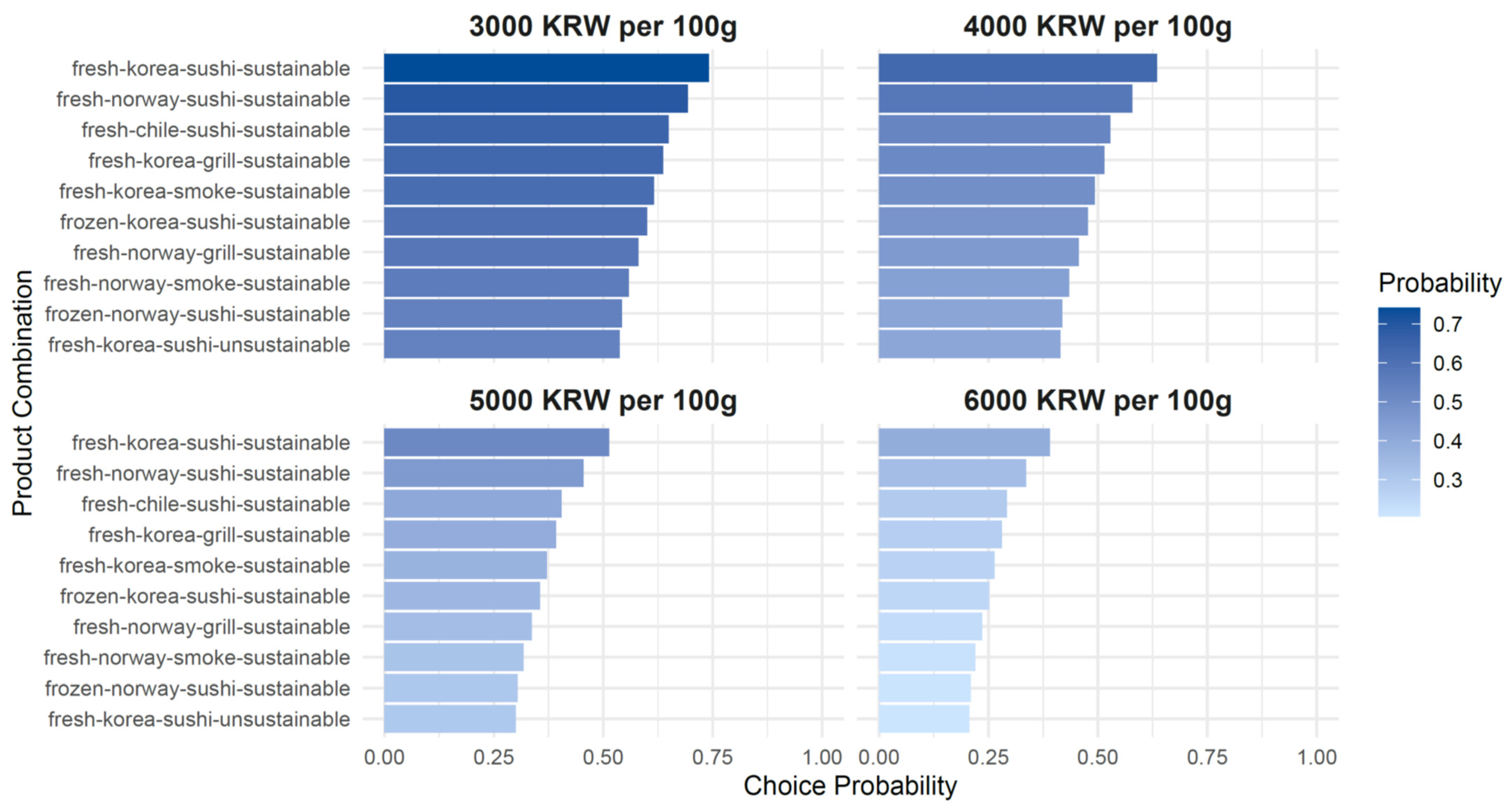

3.2. Estimation Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASC | Aquaculture Stewardship Council |

| CVM | Contingent Valuation Methods |

| COO | Country of Origin |

| DCE | Discrete Choice Experiment |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization |

| IID | Independently and Identically Distributed |

| MWTP | Marginal Willingness to Pay |

Appendix A

References

- Bostock, J.; McAndrew, B.; Richards, R.; Jauncey, K.; Telfer, T.; Lorenzen, K.; Little, D.; Ross, L.; Handisyde, N.; Gatward, I.; et al. Aquaculture: Global status and trends. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2010, 365, 2897–2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, R.L.; Hardy, R.W.; Buschmann, A.H.; Bush, S.R.; Cao, L.; Klinger, D.H.; Little, D.C.; Lubchenco, J.; Shumway, S.E.; Troell, M. A 20-year retrospective review of global aquaculture. Nature 2021, 591, 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béné, C.; Barange, M.; Subasinghe, R.; Pinstrup-Andersen, P.; Merino, G.; Hemre, G.-I.; Williams, M. Feeding 9 billion by 2050—Putting fish back on the menu. Food Secur. 2015, 7, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, J.B.C.; Kirby, M.X.; Berger, W.H.; Bjorndal, K.A.; Botsford, L.W.; Bourque, B.J.; Bradbury, R.H.; Cooke, R.; Erlandson, J.; Estes, J.A.; et al. Historical overfishing and the recent collapse of coastal ecosystems. Science 2001, 293, 629–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worm, B.; Barbier, E.B.; Beaumont, N.; Duffy, J.E.; Folke, C.; Halpern, B.S.; Jackson, J.B.C.; Lotze, H.K.; Micheli, F.; Palumbi, S.R.; et al. Impacts of biodiversity loss on ocean ecosystem services. Science 2006, 314, 787–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Costello, C.; Cao, L.; Gelcich, S.; Cisneros-Mata, M.Á.; Free, C.M.; Froehlich, H.E.; Golden, C.D.; Ishimura, G.; Maier, J.; Macadam-Somer, I.; et al. The future of food from the sea. Nature 2020, 588, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacon, A.G.J.; Metian, M. Feed matters: Satisfying the feed demand of aquaculture. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 2015, 23, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank Group. The Global Program on Fisheries (PROFISH): Catalyzing Sustainable Improvements in Fisheries and Aquaculture; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Troell, M.; Naylor, R.L.; Metian, M.; Beveridge, M.; Tyedmers, P.H.; Folke, C.; Arrow, K.J.; Barrett, S.; Crépin, A.-S.; Ehrlich, P.R.; et al. Does aquaculture add resilience to the global food system? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 13257–13263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. OECD Review of Fisheries 2025; OECD: Paris, France, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Garlock, T.M.; Asche, F.; Anderson, J.L.; Eggert, H.; Anderson, T.M.; Che, B.; Chávez, C.A.; Chu, J.; Chukwuone, N.; Dey, M.M.; et al. Environmental, economic, and social sustainability in aquaculture: The aquaculture performance indicators. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Trends in national aquaculture legislation (part II). FAO Aquac. Newsl. 2004, 31, 22–24. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Guidelines for Sustainable Aquaculture. Committee on Fisheries (COFI36). Available online: https://www.fao.org/americas/news/news-detail/cofi-36-adopto-directrices/en (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Gulbrandsen, L.H. The Emergence and Effectiveness of the Marine Stewardship Council. Mar. Policy 2009, 33, 654–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, M.F.; Almira, J. NGO and Global Voluntary Standards in Sustainable Seafood: The case of Aquaculture Stewardship Council (ASC) in Indonesia. J. Environ. Dev. 2023, 32, 165–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, L. Understanding aquaculture certification. Rev. Colomb. Cienc. Pecu. 2009, 22, 319–329. [Google Scholar]

- Vince, J.; Haward, M. Hybrid governance in aquaculture: Certification schemes and third party accreditation. Aquaculture 2019, 507, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpa, R.; Rose, J.M. Design efficiency for non-market valuation with choice modelling: How to measure it, what to report and why. Aust. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2008, 52, 253–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davide, M.; Thong Tien, N.; Giovanni, S.; Dimitar, T.; Sterenn, L.; José Luis Santiago, C.-R.; Cristina, M. Consumers’ preferences and willingness to pay for fish products with jealth and environmental labels: Evidence from five European countries. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Kallas, Z. Meta-analysis of consumers’ willingness to pay for sustainable food products. Appetite 2021, 163, 105239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S. Willingness-to-pay for sustainable aquaculture products: Evidence from Korean red seabream aquaculture. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, N.B.; Vo, D.V.; Rowley, C. Contingent valuation versus choice experiment: Estimating the willingness to pay for organic oranges in Vietnam. J. Trade Sci. 2024, 12, 268–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrontino, A.; Madau, F.; Frem, M.; Fucilli, V.; Bianchi, R.; Campobasso, A.A.; Pulina, P.; Bozzo, F. Seafood Choice and Consumption Behavior: Assessing the Willingness to Pay for an Edible Sea Urchin. Foods 2023, 12, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ge, J.; Ma, Y. Urban Chinese Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Pork with Certified Labels: A Discrete Choice Experiment. Sustainability 2018, 10, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrowclough, M.J.; Alwang, J. Conservation agriculture in Ecuador’s highlands: A discrete choice experiment. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2018, 20, 2681–2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong Ngoc, P.; Vo Tat, T.; Hoai Nguyen, T. The Effect of Sustainability Labels on Farmed-Shrimp Preferences: Insights from a Discrete Choice Experiment in Vietnam. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 2022, 27, 468–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onozaka, Y.; Honkanen, P.; Altintzoglou, T. Sustainability, perceived quality and country of origin of farmed salmon: Impact on consumer choices in the USA, France and Japan. Food Policy 2023, 117, 102452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.B.; Cho, S.R.; Mok, J.S. Antimicrobial Resistance of Fecal-Indicator Bacteria Isolated From Aquatic Animal Farms Along the Korean Coast. Aquac. Res. 2023, 2023, 5014754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penny, B.; Jun, N.; Elizabeth, S.C. Exploring seafood choices at the point of purchase among a sample of Swedish consumers. Br. Food J. 2024, 126, 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winnie, Y.; Duncan, K.; Wolfgang, H.; Ryan, T. Valuing the Willingness-to-Pay for Sustainable Seafood: Integrated Multitrophic Versus Closed Containment Aquaculture. Can. J. Agric. Econ. Rev. Can. D Agroecon. 2017, 65, 93–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, B.B.; Sandorf, E.D. Potential for Sustainable Aquaculture: Insights From Discrete Choice Experiments. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2020, 77, 401–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed Johnson, F.; Lancsar, E.; Marshall, D.; Kilambi, V.; Muhlbacher, A.; Regier, D.A.; Bresnahan, B.W.; Kanninen, B.; Bridges, J.F. Constructing Experimental Designs for Discrete-Choice Experiments: Report of the ISPOR Conjoint Analysis Experimental Design Good Research Practices Task Force. Value Health 2013, 16, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marschak, J. Binary Choice Constraints on Random Utility Indicators; Cowles Foundation Discussion Papers: New Haven, CT, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- McFadden, D. Conditional Logit Analysis of Qualitative Choice Behavior. In Frontiers in Econometrics; Zarembka, P., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1974; pp. 105–142. [Google Scholar]

- Jumamyradov, M.; Craig, B.M.; Munkin, M.; Greene, W. Comparing the conditional logit estimates and true parameters under preference heterogeneity: A simulated discrete choice experiment. Econometrics 2023, 11, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.-E.; Park, S.-H.; Lee, H.-D. Estimation of consumer value on import management of seafood obtained from IUU fishing: Using choice experiment method. J. Korea Trade 2023, 27, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, S.; Azzopardi, E.; Fox, C.; Chiaroni, E.; Payne, E.; Kenter, J. The importance of local fisheries as a cultural attribute: Insight from a discrete choice experiment of seafood consumers. Marit. Stud. 2023, 22, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallo, Y.; Nuhriwangsa, A.M.P.; Hanim, D. Purchasing power, fruits vegetables consumption, nutrition status among elementary school student. Int. J. Public Health Sci. 2019, 8, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronnmann, J.; Asche, F. Sustainable seafood from aquaculture and wild fisheries: Insights from a discrete choice experiment in Germany. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 142, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, H.; Eric, H.; Andrew, W.S.; Sofia, B.V.-B. Measuring willingness to pay for environmental attributes in seafood. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2019, 73, 307–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banović, M.; Reinders, M.J.; Claret, A.; Guerrero, L.; Krystallis, A. A cross-cultural perspective on impact of health and nutrition claims, country-of-origin and eco-label on consumer choice of new aquaculture products. Food Res. Int. 2019, 123, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankamah-Yeboah, I.; Nielsen, M.; Nielsen, R. Price pemium of organic salmon in Danish retail sale. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 122, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, H.; Jinap, S.; Mad, S.; Alias, R. Eliciting Malaysian consumer preferences for marine fish attributes by using conjoint analysis. World Appl. Sci. J. 2013, 28, 2054–2060. [Google Scholar]

- Kevin, D.R.; Daniel, K.L.; Rosemary, A.K. A random coefficients model of seafood demand: Implications for consumer preferences and substitution patterns. Mar. Resour. Econ. 2023, 38, 113–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, W. Taste, sustainability, and nutrition: Consumers’ attitude toward innovations in aquaculture products. Aquaculture 2024, 587, 740834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Attribute | Levels |

|---|---|

| Product type | 1. Fresh, 2. Frozen |

| Country of origin | 1. Korea, 2. Norway, 3. Chile |

| Preparation methods | 1. Sushi, 2. Grilled, 3. Smoked |

| Sustainability certification | 1. Sustainable, 2. Unsustainable |

| Price | Five levels of prices based on the market conditions: |

| Research Samples | Reference Population Characteristics * | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Category | n | % | Variable | Category | n | % |

| Gender | Female | 489 | 48.9 | Gender | Female | 25,846,661 | 49.99% |

| Male | 511 | 51.1 | Male | 25,837,903 | 50.01% | ||

| Age | 20s | 183 | 18.3 | Age | 20s | 6,136,764 | 13.16% |

| 30s | 188 | 18.8 | 30s | 6,975,568 | 14.96% | ||

| 40s | 222 | 22.2 | 40s | 7,717,016 | 16.55% | ||

| 50s | 235 | 23.5 | 50s | 8,660,370 | 18.57% | ||

| 60 and above | 172 | 17.2 | 60 and above | 17,147,056 | 36.77% | ||

| Marital Status | Married | 646 | 64.6 | Marital Status | Married | 30,269,089 | 68.9% |

| Unmarried | 354 | 35.4 | Unmarried | 13,688,458 | 31.1% | ||

| Monthly Income | Less than $1441 | 67 | 6.7 | Average monthly income | $3757 | - | |

| $1441–$2154 | 136 | 13.6 | |||||

| $2154–$2877 | 149 | 14.9 | |||||

| $2877–$3590 | 163 | 16.3 | |||||

| $3590–$4303 | 136 | 13.6 | |||||

| $4303–$5741 | 175 | 17.5 | |||||

| $5741 or more | 174 | 17.4 | |||||

| Variables | Coef. | Robust SE | z | p-Value | 95% Conf. Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product type (ref. Frozen) | ||||||

| Fresh *** | 0.6465 | 0.0317 | 20.41 | 0.000 | 0.584 | 0.709 |

| Country of origin (ref. Chile) | ||||||

| Korea *** | 0.4374 | 0.0813 | 5.38 | 0.000 | 0.278 | 0.597 |

| Norway *** | 0.2010 | 0.0450 | 4.46 | 0.000 | 0.113 | 0.289 |

| Preparation (ref. Smoked) | ||||||

| Sushi *** | 0.5814 | 0.0627 | 9.28 | 0.000 | 0.459 | 0.704 |

| Grilled | 0.0879 | 0.0486 | 1.81 | 0.070 | −0.007 | 0.183 |

| Sustainability (ref. Unsustainable) | ||||||

| Sustainable *** | 0.9010 | 0.0595 | 15.13 | 0.000 | 0.784 | 1.018 |

| Price *** | −0.0005 | 0.0001 | −4.01 | 0.000 | −0.001 | −0.000 |

| Constant | −0.0142 | 0.0230 | −0.62 | 0.536 | −0.059 | 0.031 |

| Product Attribute | Reference Category | Marginal WTP (KRW) | Marginal WTP (USD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainable | Unsustainable | 1850.50 | 1.33 |

| Fresh | Frozen | 1327.85 | 0.96 |

| Sushi | Smoked | 1194.15 | 0.86 |

| Korea origin | Chile | 898.38 | 0.65 |

| Norway origin | Chile | 412.77 | 0.30 |

| Grilled | Smoked | 180.55 | 0.13 |

| Product Attribute | Income Level | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Middle | High | |

| Product type (ref. Frozen) | |||

| Fresh | 0.6070 *** | 0.6620 *** | 0.6950 *** |

| (0.0555) | (0.0500) | (0.0607) | |

| Country of origin (ref. Chile) | |||

| Korea | 0.4720 *** | 0.2920 * | 0.6360 *** |

| (0.1350) | (0.1340) | (0.1550) | |

| Norway | 0.2340 ** | 0.1080 | 0.3090 *** |

| (0.0794) | (0.0719) | (0.0817) | |

| Preparation (ref. Smoked) | |||

| Sushi | 0.5710 *** | 0.4700 *** | 0.7960 *** |

| (0.0970) | (0.1080) | (0.1240) | |

| Grilled | 0.0463 | 0.0582 | 0.2020 * |

| (0.0801) | (0.0830) | (0.0900) | |

| Sustainability (ref. Unsustainable) | |||

| Sustainable | 0.7940 *** | 1.0670 *** | 0.7900 *** |

| (0.0957) | (0.0967) | (0.1210) | |

| Price | −0.0006 ** | −0.0007 *** | −0.0000 |

| (0.0002) | (0.0002) | (0.0002) | |

| Constant | −0.0180 | −0.0606 | 0.0170 |

| (0.0395) | (0.0357) | (0.0469) | |

| Model fit statistics | |||

| Observations | 7630 | 8702 | 5494 |

| Cases | 3815 | 4351 | 2747 |

| Log pseudolikelihood | −2194.72 | −2425.79 | −1544.65 |

| Wald χ2(7) | 519.81 *** | 603.33 *** | 331.92 *** |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.170 | 0.196 | 0.188 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Go, D.-H.; Yi, S. Assessing Consumer Valuation of Sustainability Certification in Seafood Products: Insight from a Discrete Choice Experiment of Korean Blue Food Market. Foods 2025, 14, 2821. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14162821

Go D-H, Yi S. Assessing Consumer Valuation of Sustainability Certification in Seafood Products: Insight from a Discrete Choice Experiment of Korean Blue Food Market. Foods. 2025; 14(16):2821. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14162821

Chicago/Turabian StyleGo, Dong-Hun, and Sangchoul Yi. 2025. "Assessing Consumer Valuation of Sustainability Certification in Seafood Products: Insight from a Discrete Choice Experiment of Korean Blue Food Market" Foods 14, no. 16: 2821. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14162821

APA StyleGo, D.-H., & Yi, S. (2025). Assessing Consumer Valuation of Sustainability Certification in Seafood Products: Insight from a Discrete Choice Experiment of Korean Blue Food Market. Foods, 14(16), 2821. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14162821