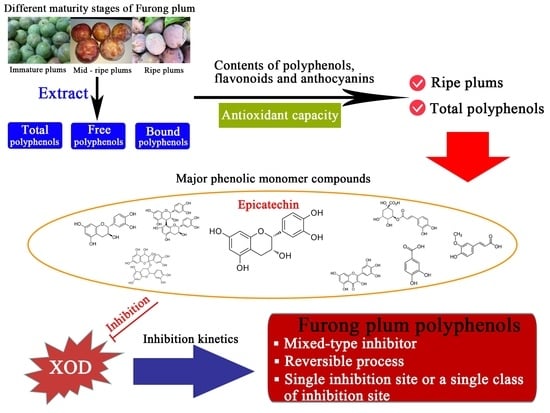

Polyphenol Composition, Antioxidant Capacity and Xanthine Oxidase Inhibition Mechanism of Furong Plum Fruits at Different Maturity Stages

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

2.2. Main Reagents

2.3. Experimental Methods

2.3.1. Extraction of Free Polyphenols

2.3.2. Extraction of Bound Polyphenols

2.3.3. Determination of Polyphenol Content

2.3.4. Determination of Flavonoid Content

2.3.5. Determination of Anthocyanin Content

2.3.6. Determination of DPPH-Clearance

2.3.7. Determination of Hydroxyl Radical Scavenging Rate

2.3.8. Identification of Phenolic Substance Components

2.4. Inhibition Mechanism of XOD

2.4.1. XOD Activity Assay

2.4.2. Inhibitory Kinetic Analysis of XOD

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Polyphenol Content

3.2. Flavonoid Content

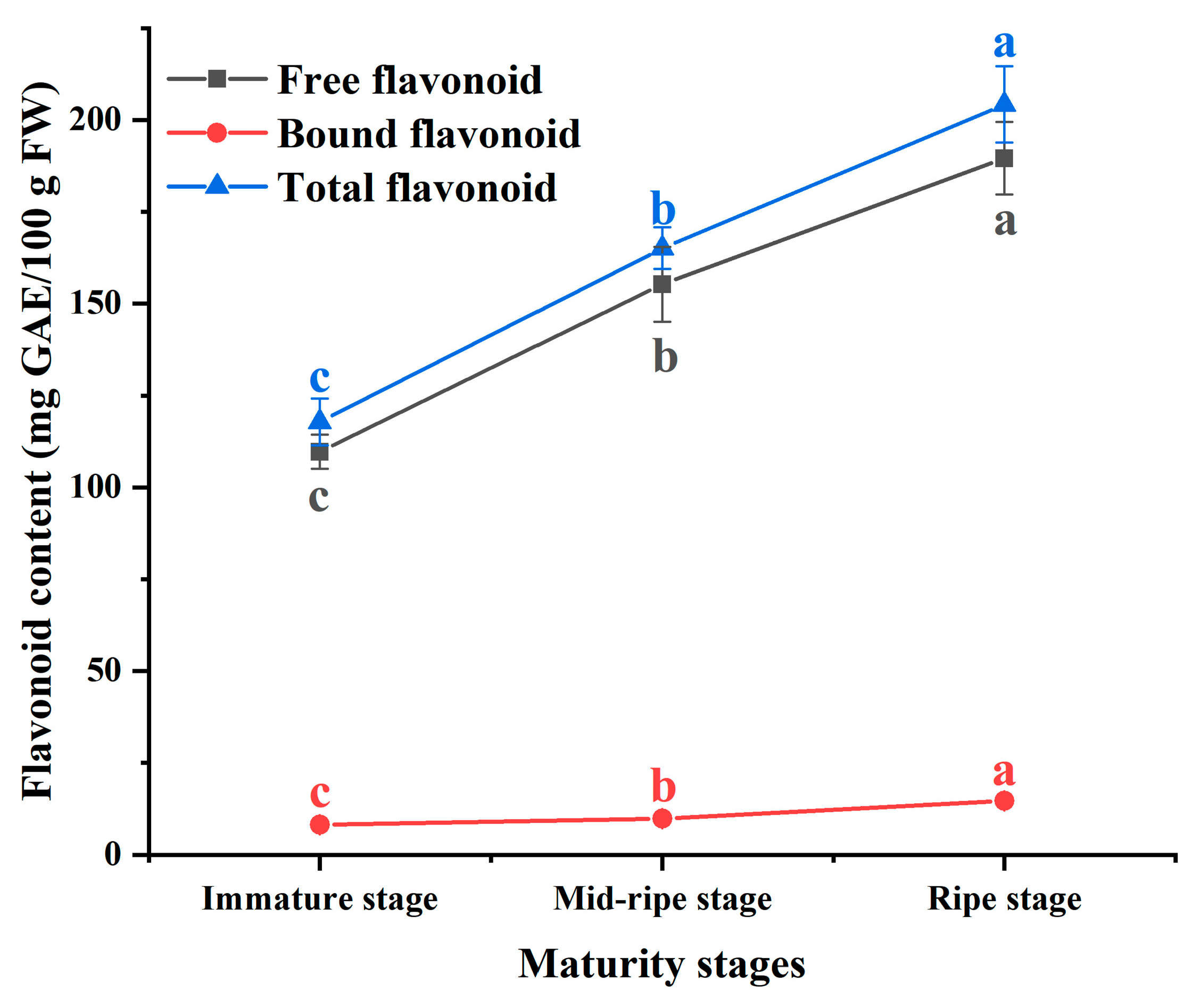

3.3. Anthocyanin Content

3.4. Antioxidant Capacity

3.5. Major Phenolic Monomer Compounds

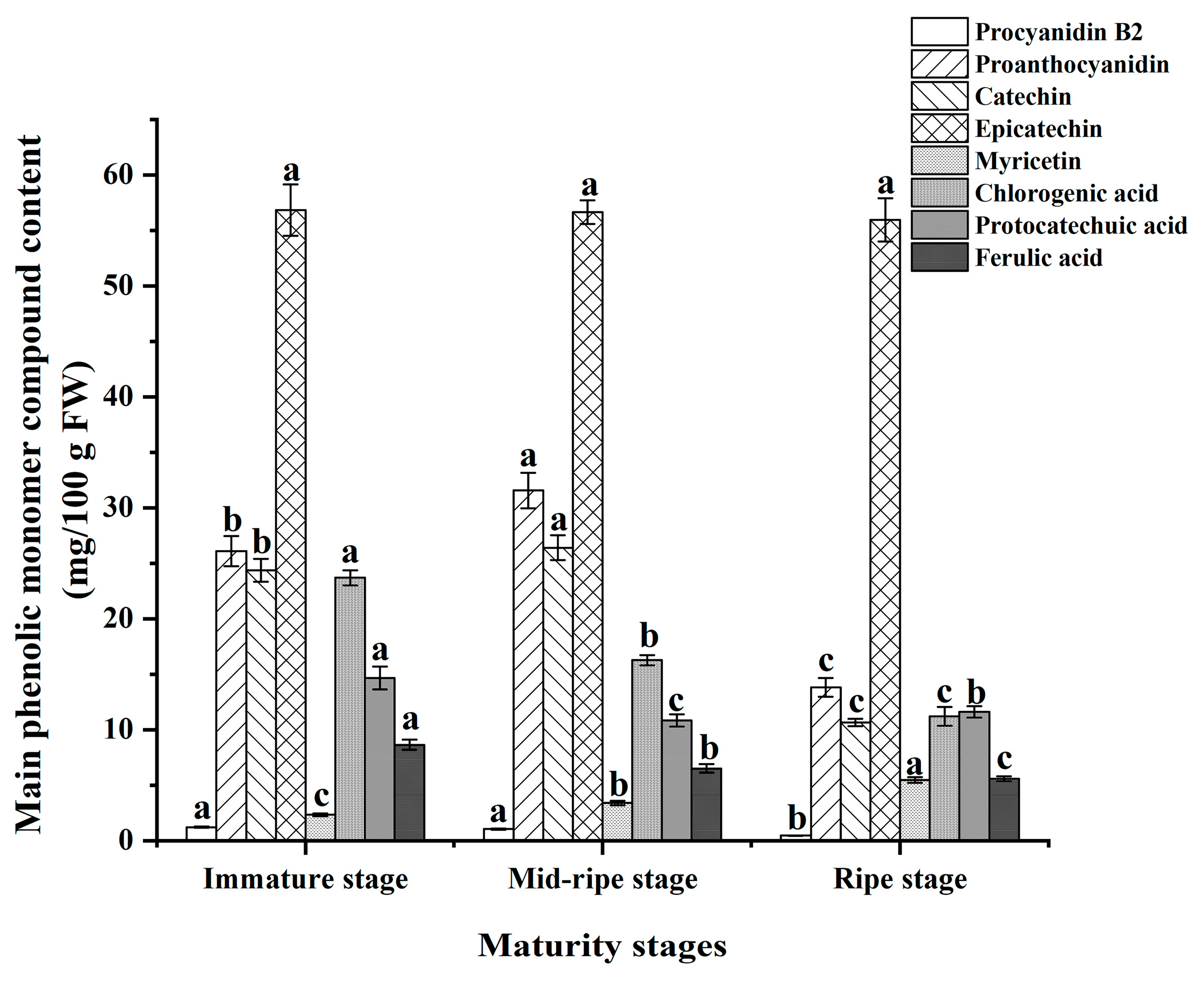

3.6. The Effect of Polyphenols from Furong Plums on the Inhibition Rate of XOD

3.7. Reversibility Analysis of XOD Inhibition by Furong Plum Polyphenols

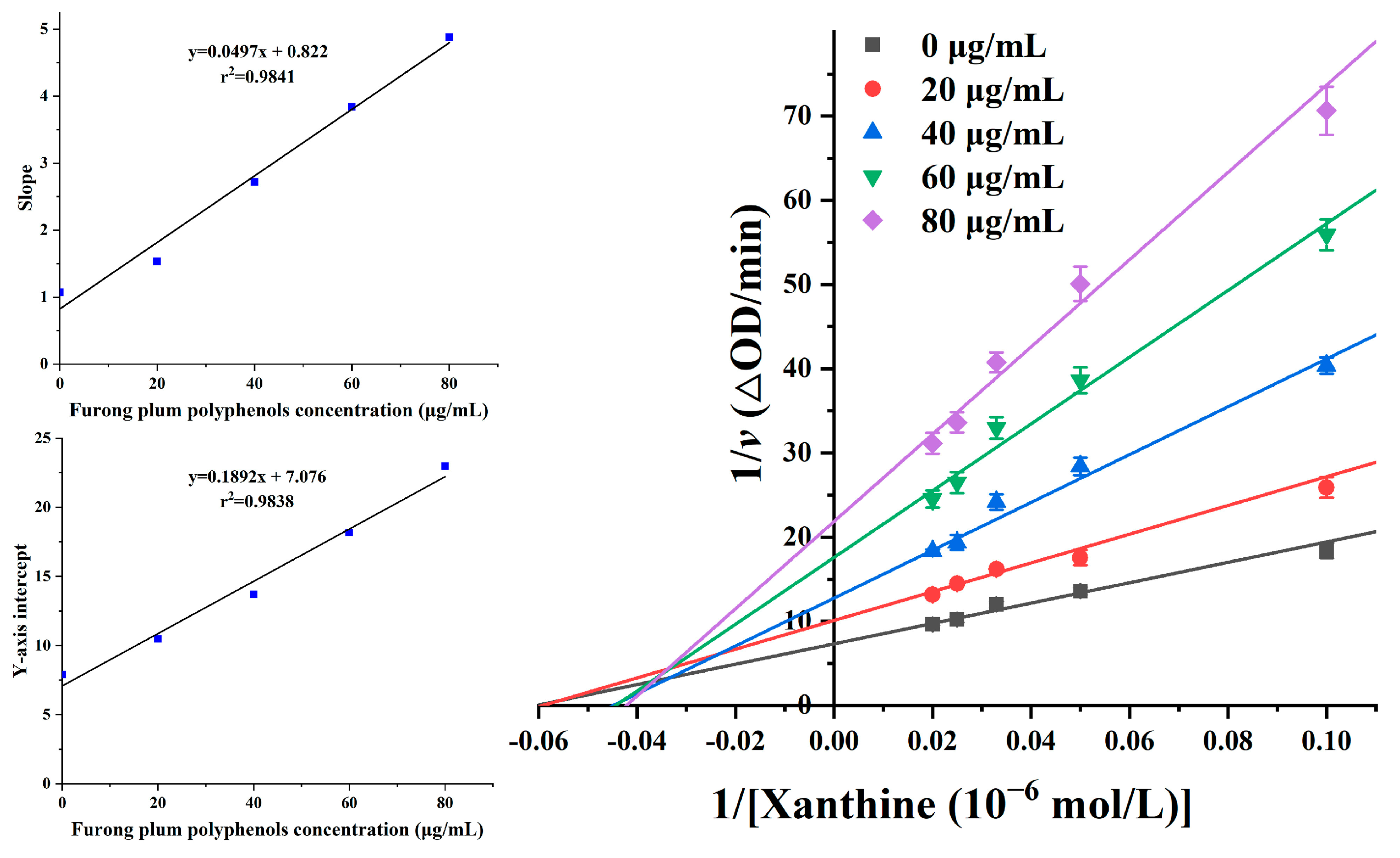

3.8. Inhibitory Mechanism of Furong Plum Polyphenols on XOD

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jiang, C.; Zeng, S.; Yang, J.; Wang, X. Genome-wide identification and expression profiling analysis of SWEET family genes involved in fruit development in plum (Prunus salicina Lindl). Genes 2023, 14, 1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.-Z.; Zhou, D.-R.; Ye, X.-F.; Jiang, C.-C.; Pan, S.-L. Identification of candidate anthocyanin-related genes by transcriptomic analysis of ‘Furongli’ plum (Prunus salicina Lindl.) during fruit ripening using RNA-Seq. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinojosa-Nogueira, D.; Pérez-Burillo, S.; García-Rincón, I.; Rufián-Henares, J.A.; Pastoriza, S. A useful and simple tool to evaluate and compare the intake of total dietary polyphenols in different populations. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 3818–3824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sójka, M.; Kolodziejczyk, K.; Milala, J.; Abadias, M.; Viñas, I.; Guyot, S.; Baron, A. Composition and properties of the polyphenolic extracts obtained from industrial plum pomaces. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 12, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seke, F.; Manhivi, V.E.; Shoko, T.; Slabbert, R.M.; Sultanbawa, Y.; Sivakumar, D. Extraction optimisation, hydrolysis, antioxidant properties and bioaccessibility of phenolic compounds in natal plum fruit (Carissa macrocarpa). Food Biosci. 2021, 44, 101425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaudanskas, M.; Okulevičiūtė, R.; Lanauskas, J.; Kviklys, D.; Zymonė, K.; Rendyuk, T.; Žvikas, V.; Uselis, N.; Janulis, V. Variability in the content of phenolic compounds in plum fruit. Plants 2020, 9, 1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goosen, N.; Oosthuizen, D.; Stander, M.; Dabai, A.; Pedavoah, M.; Usman, G. Phenolics, organic acids and minerals in the fruit juice of the indigenous African sourplum (Ximenia caffra Olacaceae). S. Afr. J. Bot. 2018, 119, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubarak, A.; Swinny, E.E.; Ching, S.Y.L.; Jacob, S.R.; Lacey, K.; Hodgson, J.M.; Croft, K.D.; Considine, M.J. Polyphenol composition of plum selections in relation to total antioxidant capacity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 10256–10262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, A.; Joubert, E.; de Beer, D. Nutraceutical value of yellow- and red-fleshed South African plums (Prunus salicina Lindl.): Evaluation of total antioxidant capacity and phenolic composition. Molecules 2014, 19, 3084–3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestario, L.N.; Howard, L.R.; Brownmiller, C.; Stebbins, N.B.; Liyanage, R.; Lay, J.O. Changes in polyphenolics during maturation of Java plum (Syzygium cumini Lam.). Food Res. Int. 2017, 100, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R. Structure and function of xanthine oxidoreductase: Where are we now? Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2002, 33, 774–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, K.; Matsumoto, K.; Hille, R.; Eger, B.T.; Pai, E.F.; Nishino, T. The crystal structure of xanthine oxidoreductase during catalysis: Implications for reaction mechanism and enzyme inhibition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 7931–7936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Hu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, C.; Li, Z.; Wen, T.; Zhuang, W.; Zou, J.; Hong, L.; et al. Metformin ameliorates high uric acid-induced insulin resistance in skeletal muscle cells. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2017, 443, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Zhang, S.; Li, W.; Wang, L.; Liu, H.; Li, W.; Zhang, T.; Liu, G.; Du, Y.; Leng, J. Prevalence of hyperuricemia and its related risk factors among preschool children from China. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Hu, J.; Song, N.; Chen, R.; Zhang, T.; Ding, X. Hyperuricemia increases the risk of acute kidney injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Nephrol. 2017, 18, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi, D.; Ferri, L.; Desideri, G.; Di Giosia, P.; Cheli, P.; Del Pinto, R.; Properzi, G.; Ferri, C. Chronic hyperuricemia, uric acid deposit and cardiovascular risk. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2013, 19, 2432–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Kan, J.; Cai, H.; Hong, J.; Jin, C.; Zhang, M. In vitro and in vivo ameliorative effects of polyphenols from purple potato leaves on renal injury and associated inflammation induced by hyperuricemia. J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46, e14049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Tan, M.-L.; Li, K.-K.; Leung, P.-C.; Ko, C.-H. Green tea polyphenols decreases uric acid level through xanthine oxidase and renal urate transporters in hyperuricemic mice. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 175, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Cao, X.; Zhao, H.; Yang, E.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, N.; Cao, W. Impact of Camellia japonica bee pollen polyphenols on hyperuricemia and gut microbiota in potassium oxonate-induced mice. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nile, S.H.; Keum, Y.S.; Nile, A.S.; Kwon, Y.D.; Kim, D.H. Potential cow milk xanthine oxidase inhibitory and antioxidant activity of selected phenolic acid derivatives. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2018, 32, e22005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, H.K.; Bhagat, K.; Singh, A.; Kumar, N.; Kaur, A.; Sharma, A.; Heer, S.; Singh, H.; Singh, J.V.; Bedi, P.M.S. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of novel indolinedione-coumarin hybrids as xanthine oxidase inhibitors. Med. Chem. Res. 2020, 29, 1632–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adom, K.K.; Liu, R.H. Antioxidant activity of grains. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 6182–6187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hu, Q.; Jiang, S.; Li, F.; Lin, J.; Han, L.; Hong, Y.; Lu, W.; Gao, Y.; Chen, D. Flos Chrysanthemi indici protects against hydroxyl-induced damages to DNA and MSCs via antioxidant mechanism. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2015, 19, 454–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanpour, H.; Alizadeh, S. Evaluation of phenolic compound, antioxidant activities and antioxidant enzymes of barberry genotypes in Iran. Sci. Hortic. 2016, 200, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zia, M.P.; Alibas, I. The effect of different drying techniques on color parameters, ascorbic acid content, anthocyanin and antioxidant capacities of cornelian cherry. Food Chem. 2021, 364, 130358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, R.; Karaköse, H.; Rühmann, S.; Goldner, K.; Neumüller, M.; Treutter, D.; Kuhnert, N. Identification of phenolic compounds in plum fruits (Prunus salicina L. and Prunus domestica L.) by high-performance liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry and characterization of varieties by quantitative phenolic fingerprints. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 12020–12031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeb, A. Concept, mechanism, and applications of phenolic antioxidants in foods. J. Food Biochem. 2020, 44, e13394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahham, S.S.; Agha, M.T.; Tabana, Y.M.; Majid, A.M.S.A. Antioxidant activities and anticancer screening of extracts from banana fruit (Musa sapientum). Am. J. Cancer Res. 2015, 8, 28–34. [Google Scholar]

- Vlaic, R.A.; Muresan, V.; Muresan, A.E.; Muresan, C.C.; Paucean, A.; Mitre, V.; Chis, S.M.; Muste, S. The changes of polyphenols, flavonoids, anthocyanins and chlorophyll content in plum peels during growth phases: From fructification to ripening. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj-Napoca 2018, 46, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, M.C.; Pinto, D.C.G.A.; Silva, A.M.S. Plant flavonoids: Chemical characteristics and biological activity. Molecules 2021, 26, 5377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, H.; Hu, L.; Lu, H.; Wei, T.; Chen, Q. Metabolic engineering of microbial cell factories for biosynthesis of flavonoids: A review. Molecules 2021, 26, 4522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yao, L.; Zhao, F.; Yu, A.; Zhou, Y.; Wen, Q.; Wang, J.; Zheng, T.; Chen, P. Protein and peptide-based nanotechnology for enhancing stability, bioactivity, and delivery of anthocyanins. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2023, 12, 2300473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Wang, R.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Luo, H.; Chen, S.; Zeng, X.; Han, Z. Acylation of anthocyanins and their applications in the food industry: Mechanisms and recent research advances. Foods 2022, 11, 2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodagoda, G.; Hong, H.T.; O’hare, T.J.; Sultanbawa, Y.; Topp, B.; Netzel, M.E. Effect of storage on the nutritional quality of queen garnet plum. Foods 2021, 10, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Xiang, F.; He, F. Polyphenols from Artemisia argyi leaves: Environmentally friendly extraction under high hydrostatic pressure and biological activities. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 171, 113951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.-G.; Chi, Y.; Cao, Y.-Q.; Zheng, M.; Deng, Z.-Y.; Cai, M.; Yang, K.; Sun, P.-L. Preparation process optimization of peptides from Agaricus blazei murrill, and comparison of their antioxidant and immune-enhancing activities separated by ultrafiltration membrane technology. Foods 2023, 12, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Wang, S.; Yang, Y.; Luo, J.; Yang, R.; Li, W. Profiles of free and bound phenolics and their antioxidant capacity in rice bean (Vigna umbellata). Foods 2023, 12, 2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laya, A.; Koubala, B.B. Polyphenols in cassava leaves (Manihot esculenta crantz) and their stability in antioxidant potential after in vitro gastrointestinal digestion. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisto, M.; Schiano, E.; Novellino, E.; Piccolo, V.; Iannuzzo, F.; Salviati, E.; Summa, V.; Annunziata, G.; Tenore, G.C. Application of a rapid and simple technological process to increase levels and bioccessibility of free phenolic compounds in annurca apple nutraceutical product. Foods 2022, 11, 1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Qu, C.; Jiang, S.; Chen, Z.; Xu, H.; Fang, H.; Su, M.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, W.; et al. The proanthocyanidin-specific transcription factor MdMYBPA1 initiates anthocyanin synthesis under low-temperature conditions in red-fleshed apples. Plant J. 2018, 96, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Song, Y.; Lin, J.; Dixon, R.A. The complexities of proanthocyanidin biosynthesis and its regulation in plants. Plant Commun. 2023, 4, 100498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalbert, A.; Manach, C.; Morand, C.; Rémésy, C.; Jiménez, L. Dietary polyphenols and the prevention of diseases. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2005, 45, 287–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Tang, D.; Liu, X.; Cheng, J.; Wang, X.; Guo, D.; Zou, J.; Yang, H. Phenolic profile and antioxidant activity of longan pulp of different cultivars from South China. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 165, 113698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhou, H.; Song, L.; Yang, Z.; Qiu, M.; Wang, J.; Shi, S. Anthocyanins: Promising natural products with diverse pharmacological activities. Molecules 2021, 26, 3807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Hu, X.; Shi, Q.; Lu, Y.; Yan, J.; Wu, D.-T.; Qin, W. Changes in the fruit quality, phenolic compounds, and antioxidant potential of red-fleshed kiwifruit during postharvest ripening. Foods 2023, 12, 1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, L.; Lu, L.; Zhao, X.; Xiong, W.; Xu, H.; Wu, S. Effects of natural antioxidants on the oxidative stability of Eucommia ulmoides seed oil: Experimental and molecular simulation investigations. Food Chem. 2022, 383, 132640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leopoldini, M.; Russo, N.; Toscano, M. The molecular basis of working mechanism of natural polyphenolic antioxidants. Food Chem. 2011, 125, 288–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Song, D.; Zhao, X. Potential applications and preliminary mechanism of action of dietary polyphenols against hyperuricemia: A review. Food Biosci. 2021, 43, 101297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baki Kekilli, E.; Orhan, I.E.; Senol Deniz, F.S.; Eren, G.; Emerce, E.; Kahraman, A.; Aysal, I.A. Erodium birandianum Ilarslan & Yurdak. shows anti-gout effect through xanthine oxidase inhibition: Combination of in vitro and in silico techniques and profiling of main components by LC-Q-ToF-MS. Phytochem. Lett. 2021, 43, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaezi, M. Evaluation of quercetin omega-6 and-9 esters on activity and structure of mushroom tyrosinase: Spectroscopic and molecular docking studies. J. Food Biochem. 2021, 45, e13953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Gong, Y.; Li, J.; Fan, L. In vitro inhibitory effects of polyphenols from tartary buckwheat on xanthine oxidase: Identification, inhibitory activity, and action mechanism. Food Chem. 2022, 379, 132100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, M.; Zheng, M.; Cui, J.; Liu, Z.; Liu, C.; Liu, S. Rapid screening and evaluation of XOD inhibitors and O-2(center dot-) scavenger from total flavonoids of Ginkgo biloba leaves by LC-MS and multimode microplate reader. Biomed. Chromatogr. 2020, 34, e4852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hou, Y.; Si, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhang, S.; Sun, S.; Liu, X.; Wang, R. Isolation, characterization, and xanthine oxidase inhibitory activities of flavonoids from the leaves of Perilla frutescens. Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 34, 2566–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Zhu, H.; Liu, J.; Fan, H.; Sun, L.; Lu, W.; Liu, X.; Li, L. 3,5,2′,4′-Tetrahydroxychalcone, a new non-purine xanthine oxidase inhibitor. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2011, 189, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Maturity Stages | IC50 of the DPPH Scavenging (μg/mL) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Free Polyphenols | Bound Polyphenols | Total Polyphenols | |

| Immature stage | 98.48 ± 1.57 a | 39.14 ± 1.02 a | 59.63 ± 1.28 a |

| Mid-ripe stage | 45.99 ± 1.02 b | 29.67 ± 0.48 b | 34.28 ± 0.54 b |

| Ripe stage | 38.57 ± 0.84 c | 22.69 ± 0.58 c | 28.19 ± 0.67 c |

| Maturity Stages | IC50 of ·OH Scavenging (μg/mL) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Free Polyphenols | Bound Polyphenols | Total Polyphenols | |

| Immature stage | 249.63 ± 7.40 a | 121.42 ± 6.92 a | 192.69 ± 5.48 a |

| Mid-ripe stage | 246.81 ± 7.42 a | 126.65 ± 3.68 a | 188.57 ± 6.81 a |

| Ripe stage | 253.66 ± 8.96 a | 116.78 ± 4.54 a | 198.16 ± 7.55 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zheng, Z.; Wu, L.; Deng, W.; Yi, K.; Li, Y. Polyphenol Composition, Antioxidant Capacity and Xanthine Oxidase Inhibition Mechanism of Furong Plum Fruits at Different Maturity Stages. Foods 2023, 12, 4253. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12234253

Zheng Z, Wu L, Deng W, Yi K, Li Y. Polyphenol Composition, Antioxidant Capacity and Xanthine Oxidase Inhibition Mechanism of Furong Plum Fruits at Different Maturity Stages. Foods. 2023; 12(23):4253. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12234253

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Zhipeng, Li Wu, Wei Deng, Kexin Yi, and Yibin Li. 2023. "Polyphenol Composition, Antioxidant Capacity and Xanthine Oxidase Inhibition Mechanism of Furong Plum Fruits at Different Maturity Stages" Foods 12, no. 23: 4253. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12234253

APA StyleZheng, Z., Wu, L., Deng, W., Yi, K., & Li, Y. (2023). Polyphenol Composition, Antioxidant Capacity and Xanthine Oxidase Inhibition Mechanism of Furong Plum Fruits at Different Maturity Stages. Foods, 12(23), 4253. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12234253