“The Good, The Bad, and the Minimum Tolerable”: Exploring Expectations of Institutional Food

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Findings and Discussion

3.1. Expectation Functions

“The most important thing to me is freedom of choice… and a good glass of wine”(male, aged 64)

“What would be ideal, and a bit of a luxury, would be that when lunch and dinner time approaches, you would get a menu”(female, aged 60)

“I definitely believe future residents will think they should be able to expect more international food in institutions. Today, we have a lot of variation in food because we have changed our diet to something completely different. Our diet is much more internationalized, and thus people will demand more choice alternatives. Before it was fish, potato dumplings and minced meat. Today, you need to add tacos and stuff like that”(Male, aged 59)

“The kitchen has to be placed in the institution if you want to serve local food and personalize the meals after needs, which is something I think should be prioritized”(Male, aged 77)

“When you get in the last stage of life, then you should be able to choose what you want to eat yourself. It should not even be a question—the elderly should be satisfied and prioritized.”(Female, aged 68)

“I would like to have varied food (as in internationalization). But you cannot really expect that I think… but ideally, I would like some variation”(male, aged 70)

“I think there are miles of distance between the reality of institutional food, and how it should be”.(Female, aged 73)

“My neighbor had her husband in a nursing home. He was so thin because he was sick, but let me tell you, he lost even more weight up there (at the nursing home), and he was not the only one. Everyone talked about it, that they lost weight there due to insufficient food”(Female, aged 78)

“The food should be healthy and taste good. And adequate portions. That’s really at a minimum level. If I were to go a bit above that, I would say it should look appetizing—but that is also minimum actually”(female, aged 60)

Predictive: “Realistically, I’m not expecting any restaurant luxury. But that it is an average Norwegian diet”(male, aged 64)

Minimum tolerable: “It should be good warm and appetizing food. In a cozy environment. That is at a minimum level. And good service. It’s important for the atmosphere”(Female, aged 60)

3.2. Interconnected Expectations

“Ideally, I would expect to be able to choose whatever I want (to eat), but realistically I guess you cannot expect that”(Female, aged 73)

“When it comes to elderly in nursing homes, I think we should not talk about a minimum. They have paid their taxes for all their years, so that is no way to treat the elderly. Yes, perhaps they don’t need a 5-course dinner and wine every single day. But it should be good quality, healthy food, presented nicely, in a social, home-like environment. That would be a minimum requirement”(Female, aged 60)

3.3. Affective Expectations

“My mother did not want to go out of the room. She felt sad about the situation (in the institution). So, she stayed in her room and ate, and then she ate less and less. The food was halfway ruined when it came. It is so sad, horrifying, I think”(Female, aged 60)

“It would bring a lot of joy to sit around a table with someone you care about and share a good meal with”(Female, aged 68)

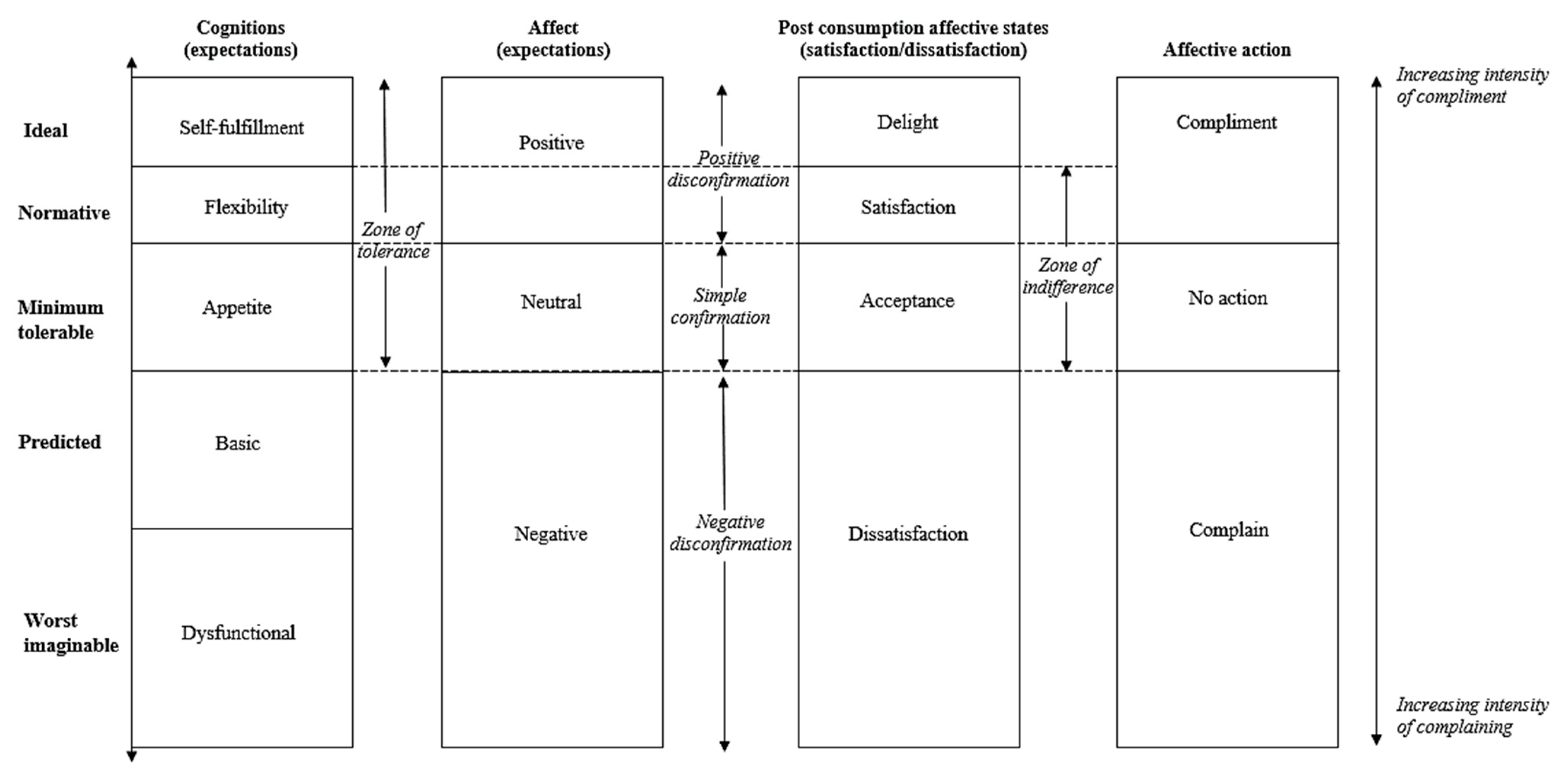

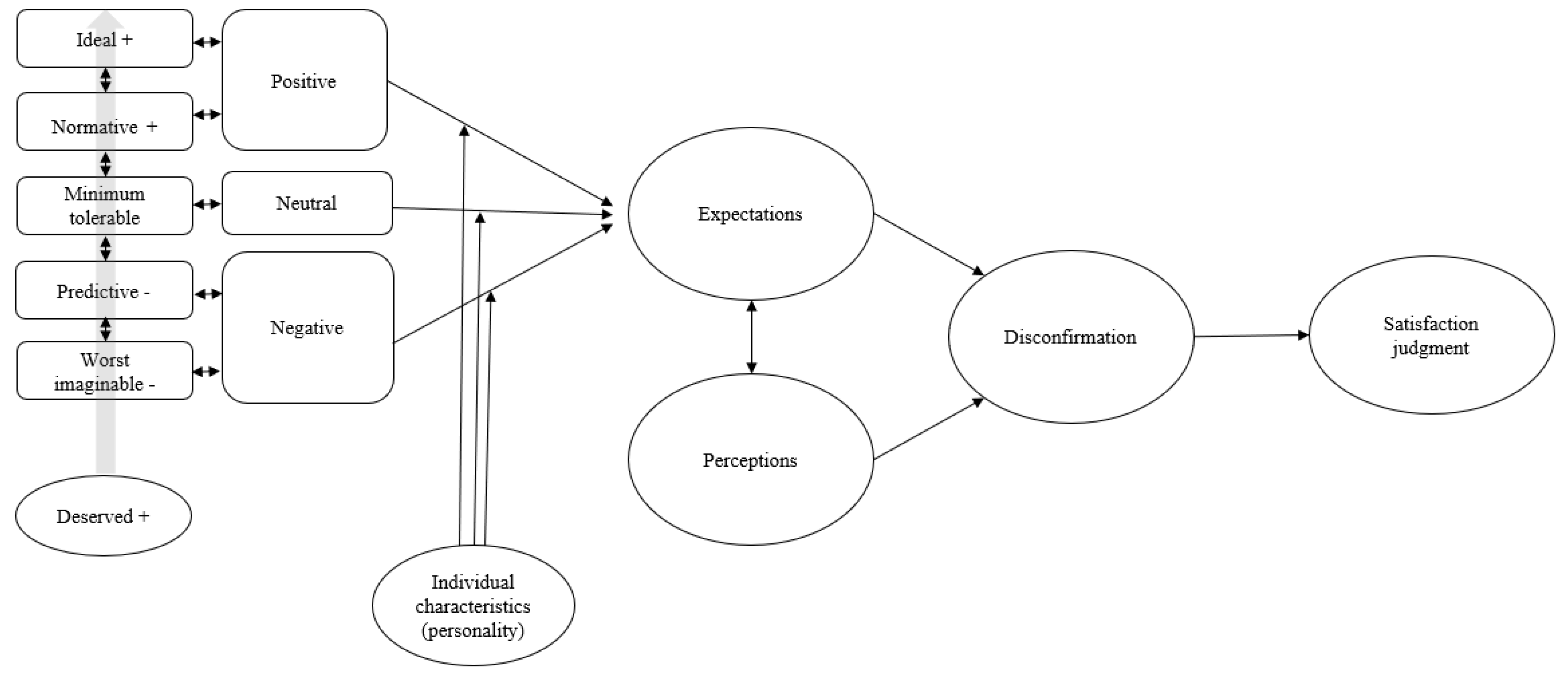

3.4. Extended Expectancy-Disconfirmation Model

3.5. Limitations

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moschis, G.P. Marketing to Older Adults: An Updated Overview of Present Knowledge and Practice. J. Consum. Mark. 2003, 20, 516–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moschis, G.P. Life Stages of the Mature Market. Am. Demogr. 1996, 18, 44. [Google Scholar]

- Reisenwitz, T.; Iyer, R. A Comparison of Younger and Older Baby Boomers: Investigating the Viability of Cohort Segmentation. J. Consum. Mark. 2007, 24, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohijoki, A.-M.; Marjanen, H. The Effect of Age on Shopping Orientation—Choice Orientation Types of the Ageing Shoppers. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2013, 20, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, M. Demographic Outlook for the European Union 2020; European Parliamentary Research Service (EPRS): Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell-Bennett, R.; Rosenbaum, M.S. Editorial: Mega Trends and Opportunities for Service Research. J. Serv. Mark. 2019, 33, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, R.; Goodwin, V.A.; Abbott, R.A.; Hall, A.; Tarrant, M. Exploring Residents’ Experiences of Mealtimes in Care Homes: A Qualitative Interview Study. BMC Geriatr. 2017, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardello, A.V.; Bell, R.; Kramer, F.M. Attitudes of Consumers toward Military and Other Institutional Foods. Food Qual. Prefer. 1996, 7, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiselman, H.L. Meals in Science and Practice: Interdisciplinary Research and Business Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; ISBN 978-1-84569-571-2. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, J.S.A.; Meiselman, H.L.; Edwards, A.; Lesher, L. The Influence of Eating Location on the Acceptability of Identically Prepared Foods. Food Qual. Prefer. 2003, 14, 647–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, O.R.L.; Connelly, L.B.; Capra, S.; Hendrikz, J. Determinants of Foodservice Satisfaction for Patients in Geriatrics/Rehabilitation and Residents in Residential Aged Care. Health Expect. 2013, 16, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wettergreen, J.; Ekornrud, T.; Abrahamsen, D. Eldrebølgen Legger Press på Flere Omsorgstjenester i Kommunen. Available online: https://www.ssb.no/helse/artikler-og-publikasjoner/eldrebolgen-legger-press-pa-flere-omsorgstjenester-i-kommunen (accessed on 7 July 2020).

- Santos, J.; Boote, J. A Theoretical Exploration and Model of Consumer Expectations, Post-Purchase Affective States and Affective Behaviour. J. Consum. Behav. 2003, 3, 142–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. A Cognitive Model of the Antecedents and Consequences of Satisfaction Decisions. J. Mark. Res. 1980, 17, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovsky, N.; Mok, J.Y.; Leon-Cazares, F. Citizen Expectations and Satisfaction in a Young Democracy: A Test of the Expectancy-Disconfirmation Model. Public Adm. Rev. 2017, 77, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanski, D.M.; Henard, D.H. Customer Satisfaction: A Meta-Analysis of the Empirical Evidence. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2001, 29, 16–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Au, A.K.M.; Tse, A.C.B. Expectancy Disconfirmation: Effects of Deviation from Expected Delay Duration on Service Evaluation in the Airline Industry. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2019, 31, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, O. Managing Citizens’ Expectations of Public Service Performance: Evidence from Observation and Experimentation in Local Government. Public Adm. 2011, 89, 1419–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poister, T.H.; Thomas, J.C. The Effect of Expectations and Expectancy Confirmation/Disconfirmation on Motorists’ Satisfaction with State Highways. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2011, 21, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizam, A.; Milman, A. Predicting Satisfaction among First Time Visitors to a Destination by Using the Expectancy Disconfirmation Theory. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 1993, 12, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. SERVQUAL: A Multiple-Item Scale for Measuring Consumer Perceptions of Service Quality. J. Retail. 1988, 64, 12–40. [Google Scholar]

- Boulding, W.; Kalra, A.; Staelin, R.; Zeithaml, V.A. A Dynamic Process Model of Service Quality: From Expectations to Behavioral Intentions. J. Mark. Res. 1993, 30, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreng, R.A.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Olshavsky, R.W. A Reexamination of the Determinants of Consumer Satisfaction. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaTour, S.A.; Peat, N.C. Conceptual and Methodological Issues in Consumer Satisfaction Research. ACR N. Am. Adv. 1979, 6, 431–437. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, R.L. Measurement and Evaluation of Satisfaction Processes in Retail Settings. J. Retail. 1981, 57, 25–48. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, R.L.; DeSarbo, W. Response Determinants in Satisfaction Judgments. J. Consum. Res. 1988, 14, 495–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, O. Evaluating the Expectations Disconfirmation and Expectations Anchoring Approaches to Citizen Satisfaction with Local Public Services. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2009, 19, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Satisfaction: A Behavioral Perspective on the Consumer; M.E. Sharpe: New York, NY, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-7656-2887-9. [Google Scholar]

- Tse, D.K.; Wilton, P.C. Models of Consumer Satisfaction Formation: An Extension. J. Mark. Res. 1988, 25, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodruff, R.B.; Cadotte, E.R.; Jenkins, R.L. Modeling Consumer Satisfaction Processes Using Experience-Based Norms. J. Mark. Res. 1983, 20, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, A.M. Rethinking Customer Expectations of Service Quality: Are Call Centers Different? J. Serv. Mark. 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgs, B.; Polonsky, M.J.; Hollick, M. Measuring Expectations: Forecast vs. Ideal Expectations. Does It Really Matter? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2005, 12, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L.; Parasuraman, A. The Nature and Determinants of Customer Expectations of Service. JAMS 1993, 21, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.A. Studying Satisfaction, Modifying Models, Eliciting Expectations, Posing Problems adn Making Meaningful Measurements. In Conceptualization and Measurement of Consumer Satisfaction and Dissatisfaction; Hunt, H.K., Ed.; Marketing Science Institute: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1977; pp. 72–91. [Google Scholar]

- Churchill, G. A Paradigm for Developing Better Measures of Marketing Constructs. J. Mark. Res. 1979, 16, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. A Conceptual Model of Service Quality and its Implications for Future Research. J. Mark. 1985, 49, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttle, F.A. Word-of-Mouth: Understanding and Managing Refferal Marketing. J. Strateg. Mark. 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L.; Winer, R.S. A Framework for the Formation and Structure of Consumer Expectations: Review and Propositions. J. Econ. Psychol. 1987, 8, 469–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, J.; Armstrong, R.W.; Johnson, L.W. The Effect of Cues on Service Quality Expectations and Service Selection in a Restaurant Setting: A Retrospective and Prospective Commentary. J. Serv. Mark. 2016, 30, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, Y. Baby Boomers Simply Refuse to Grow Up. The Observer 2000. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/theobserver/2000/nov/26/focus.news (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Asioli, D.; Aschemann-Witzel, J.; Caputo, V.; Vecchio, R.; Annunziata, A.; Næs, T.; Varela, P. Making Sense of the “Clean Label” Trends: A Review of Consumer Food Choice Behavior and Discussion of Industry Implications. Food Res. Int. 2017, 99, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ditlevsen, K.; Sandøe, P.; Lassen, J. Healthy Food is Nutritious, but Organic Food is Healthy Because it is Pure: The Negotiation of Healthy Food Choices by Danish Consumers of Organic Food. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 71, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoek, A.C.; Pearson, D.; James, S.W.; Lawrence, M.A.; Friel, S. Shrinking the Food-Print: A Qualitative Study into Consumer Perceptions, Experiences and Attitudes towards Healthy and Environmentally Friendly Food Behaviours. Appetite 2017, 108, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guiné, R.P.F.; Florença, S.G.; Barroca, M.J.; Anjos, O. The Link between the Consumer and the Innovations in Food Product Development. Foods 2020, 9, 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, N.P.; Line, N.D.; Lee, S.-M. The Health Conscious Restaurant Consumer: Understanding the Experiential and Behavioral Effects of Health Concern. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 2103–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Songsamoe, S.; Saengwong-ngam, R.; Koomhin, P.; Matan, N. Understanding Consumer Physiological and Emotional Responses to Food Products Using Electroencephalography (EEG). Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 93, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobucci, D.; Churchill, G.A. Marketing Research. Methodological Foundations, 10th ed.; South-Western, Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, H.-F.; Shannon, S.E. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NSD About NSD—Norwegian Centre for Research Data. Available online: https://nsd.no/en/about-nsd-norwegian-centre-for-research-data (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- Kjelvik, J.; Jønsberg, E. Botid i Sykehjem Og Varighet Av Tjenester Til Hjemmeboende; Helsedirektoratet: Oslo, Norway, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Leknes, S.; Løkken, S.A.; Syse, A.; Tønnessen, M. Befolkningsframskrivingene 2018; Statistisk Sentralbyrå: Oslo, Norway, 2018; ISBN 978-82-537-9767-0. [Google Scholar]

- Spiggle, S. Analysis and Interpretation of Qualitative Data in Consumer Research. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 21, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, R.; Marshall, D.W. The Construct of Food Involvement in Behavioral Research: Scale Development and Validation. Appetite 2003, 40, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pliner, P.; Hobden, K. Development of a Scale to Measure the Trait of Food Neophobia in Humans. Appetite 1992, 19, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, S.J. Consumer Attitudes toward Health and Health Care: A Differential Perspective. J. Consum. Aff. 1988, 22, 96–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.Y.; Lee, E.-H. Reducing Confusion about Grounded Theory and Qualitative Content Analysis: Similarities and Differences. Qual. Rep. 2014, 19, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Abbey, K.L.; Wright, O.R.L.; Capra, S. Menu Planning in Residential Aged Care—The Level of Choice and Quality of Planning of Meals Available to Residents. Nutrients 2015, 7, 7580–7592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, K.; Anderson, J.B.; Archuleta, M.; Kudin, J.S. Defining Skilled Nursing Facility Residents’ Dining Style Preferences. J. Nutr. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2013, 32, 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milte, R.; Ratcliffe, J.; Chen, G.; Miller, M.; Crotty, M. Taste, Choice and Timing: Investigating Resident and Carer Preferences for Meals in Aged Care Homes: Meal Preferences in Aged Care Homes. Nurs. Health Sci. 2018, 20, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geers, A.L.; Lassiter, G.D. Effects of Affective Expectations on Affective Experience: The Moderating Role of Optimism-Pessimism. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 28, 1026–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, T.D.; Lisle, D.J.; Kraft, D.; Wetzel, C.G. Preferences as Expectation-Driven Inferences: Effects of Affective Expectations on Affective Experience. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 56, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaaren, K.J.; Hodges, S.D.; Wilson, T.D. The Role of Affective Expectations in Subjective Experience and Decision-Making. Soc. Cogn. 1994, 12, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Expectation Type | Definition | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Ideal | The highest level of expectations Explained as i.e., the «wished for» level of performance [34]. | Based on needs and wants [13]. Stable over time [35]. |

| Should (normative) | What a customer feels a service should offer, rather than would offer [36]. | Based on persuasion-based antecedents or the market supplier [23]. Stable over time [18]. |

| Desired (want) | The level of performance that consumers want or hope to receive [13] | Based on mix of realistic predictions of what “can be” and what “should be” [13]. |

| Predicted (will) | What a consumer expects predict will or is likely to happen in the next interaction with the service or product [25]. | Based on past experience and perceived past performance. Less rigid than above types [18]. |

| Minimum tolerable (adequate) | The minimum acceptable baseline of performance [34]. | Implications for zone of tolerance—from ideal to minimum tolerable expectations: the extent to which consumers accept heterogeneity [33]. |

| Intolerable | A level of performance or a set of expectations the consumer will not accept [37]. | May stem from word of mouth, personal experiences, bad memories [13]. |

| Worst imaginable | The worst imaginable scenario in a given context—the “worst case scenario” [13] | May stem from media (television, news, social media, radio) [13]. |

| Deserved | The consumers view on the service encounter they fell they appropriately deserve [22]. | Related to equity theory. Can interact with any of the other expectation types from normative to minimum tolerable [13]. |

| Informant ID | Gender | Age | Marital Status | Experience with Institutional Food | Impression of Institutional Food |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID1 | Male | 77 | Married | Direct | Negative |

| ID2 | Female | 68 | Married | Indirect | Negative |

| ID3 | Male | 70 | Married | Indirect | Positive |

| ID4 | Female | 58 | Married | None | Neutral |

| ID5 | Female | 79 | Single | Indirect | Negative |

| ID6 | Female | 78 | Married | Indirect | Negative |

| ID7 | Female | 73 | Single | Direct and indirect | Negative |

| ID8 | Male | 59 | Single | Direct and indirect | Positive |

| ID9 | Female | 60 | Married | Direct and indirect | Negative |

| ID10 | Male | 66 | Single | None | Neutral |

| ID11 | Male | 64 | Married | Indirect | Neutral |

| ID12 | Female | 60 | Married | Indirect | Negative |

| ID13 | Female | 73 | Single | Direct and indirect | Negative |

| ID14 | Female | 77 | Married | Direct and indirect | Negative |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Andreassen, H.; Gjerald, O.; Hansen, K.V. “The Good, The Bad, and the Minimum Tolerable”: Exploring Expectations of Institutional Food. Foods 2021, 10, 767. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10040767

Andreassen H, Gjerald O, Hansen KV. “The Good, The Bad, and the Minimum Tolerable”: Exploring Expectations of Institutional Food. Foods. 2021; 10(4):767. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10040767

Chicago/Turabian StyleAndreassen, Hanne, Olga Gjerald, and Kai Victor Hansen. 2021. "“The Good, The Bad, and the Minimum Tolerable”: Exploring Expectations of Institutional Food" Foods 10, no. 4: 767. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10040767

APA StyleAndreassen, H., Gjerald, O., & Hansen, K. V. (2021). “The Good, The Bad, and the Minimum Tolerable”: Exploring Expectations of Institutional Food. Foods, 10(4), 767. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10040767