Abstract

AI technology is reshaping the knowledge ecosystem, bringing both challenges and opportunities to libraries. This article examines the transformation of librarians from “knowledge guardians” to “intelligent collaborators.” It discusses the professional challenges and practical dilemmas introduced by AI through the lenses of value reorientation and paradigm shift. The paper argues that librarians should actively adopt new technologies, engage in ongoing learning, and develop more resilient knowledge service systems, while also identifying their key roles and potential pathways for transformation within smart library frameworks.

1. Introduction

Throughout the evolution of human civilization, libraries have served as central institutions for the storage and dissemination of knowledge. Their spatial forms and the roles of librarians have undergone three fundamental transformations, a process that deeply reflects the leap in the forms of knowledge carriers. From the mechanization of the Industrial Revolution to the digital restructuring driven by the Information Revolution and now the intelligent leap triggered by the Artificial Intelligence Revolution, the trajectory of library transformation has always kept pace with technological innovation. Especially in the contemporary context of rapid advancements in code generation technology and the burgeoning development of quantum computing, this transformation not only reflects the evolution of human knowledge carriers but also foreshadows a profound shift in the ways civilization is transmitted.

Currently, the digital technology revolution is reshaping the ecosystem of knowledge services at an unprecedented speed. From the application of intelligent consulting robots to the construction of knowledge graphs and from the prediction of readers’ behavior to the restoration of ancient documents, artificial intelligence is redefining the service boundaries of traditional libraries. Libraries, as knowledge infrastructures, are seen as ‘embassies rooted in the world and open to the outside world’”, and Vicki McDonald, President of the IFLA, emphasizes in her foreword to the Trends 2024 report that “libraries and information workers should not be mere spectators, but at the heart of the field (IFLA). In this wave of change, the professional role of librarians is undergoing a disruptive shift, with fundamental tasks such as traditional cataloging and circulation being replaced by intelligent systems, while at the same time giving rise to emerging careers such as data literacy instructors and intelligent resource architects. This transformation not only brings the challenge of technological adaptation, but also triggers a profound reflection on the value of the profession.

The application of AI technology in the library field has raised a series of profound issues that require systematic consideration from the perspective of restructuring the knowledge dissemination system. First, in knowledge recommendation systems, how can we avoid algorithm-induced “information silos” and cognitive biases to ensure the openness and diversity of public knowledge spaces? Additionally, how should the ethical boundaries of data usage be defined to balance personalized services with privacy protection? Second, the risk of misinformation posed by generative AI presents new challenges for information literacy education, prompting libraries to develop systems for cultivating information discernment and critical thinking in the AI age. Furthermore, while machine translation technology has reduced language barriers, the preservation of multilingual literature remains indispensable for maintaining cultural diversity. In terms of service models, AI’s precise predictions may diminish the serendipity of knowledge exploration for readers, necessitating the design of “knowledge serendipity” mechanisms to compensate for algorithmic limitations (Tu & Chu, 2024; X. Wang et al., 2022). The widespread adoption of VR consulting also raises new questions: How can physical libraries maintain social trust through “human presence” and avoid technology completely replacing interpersonal interaction? After AI takes over standardized services, will libraries return to their essence of knowledge dissemination and critical thinking education? This transformation is not merely a matter of technological replacement or empowerment but also a reexamination of traditional library science theory. With these questions in mind, we will proceed to the following discussion.

The role of librarians has undergone a profound transformation from “knowledge keeper” to “intelligent collaborator”. The reshaping of the librarian’s role stems from the search for a balanced fulcrum at the intersection of digital civilization and human civilization. This is not only a question of the survival of the professional community, but also a strategic proposition related to how librarians can maintain cognitive sovereignty and continue their cultural genes in the age of AI (Feng et al., 2025; Y. Wang, 2023). This transformation is not a simple adaptation of technology, but a mode of cognition in the sense of sociology of knowledge. The evolution of the role of librarians determines whether human society can continue critical thinking and pluralistic knowledge values in the age of intelligence. When machines begin to understand knowledge, human beings need to guide knowledge toward the gradient of wisdom sublimation, which is the historic significance given to librarians in the AI-enabled age.

Overall, the profound impact of artificial intelligence on the library field and its practical applications still offers numerous topics worthy of in-depth exploration. This paper takes “From Knowledge Guardians to Intelligent Collaborators” as its starting point for reflection. Grounded in the dual dimensions of value reconstruction and paradigm innovation, it seeks to develop a more adaptive and resilient knowledge service ecosystem. We will examine the challenges AI poses to librarians’ career trajectories and analyze the practical dilemmas they currently face. As their roles evolve from “resource custodians” to “knowledge service designers,” librarians must proactively embrace technological change and engage in continuous learning to play more central roles in building smart libraries. This paper aims to explore possible directions and pathways for librarians during this transformation.

2. Technological Shock and Professional Crisis: The Reality of the Librarian’s Dilemma

2.1. The Impact of AI on the Library Industry

Artificial intelligence (AI) technology is profoundly reshaping the ecosystems of industries across the board, and the library sector—with its long-standing historical value—is no exception. From the foundational forms of knowledge services to the construction and application of knowledge graphs, and looking ahead to future knowledge navigation services (Yuan et al., 2024), AI is posing unprecedented challenges to the traditional functions, service models, and very existence of libraries. The most significant impact is evident in the fundamental transformation of users’ information-seeking behaviors (Tong & Chen, 2025). AI-driven search engines, intelligent recommendation systems (such as algorithms similar to those used by TikTok or AIGC), and knowledge graphs can respond to user queries at unprecedented speeds and with unparalleled precision, and can even directly generate answers or summaries. Intelligent consultation systems represented by ChatGPT, DeepSeek, and Kimi have become widely available, enabling users to access consultation answers, optimized book information, and personalized book and digital resource recommendations in real time via mobile devices or smart terminals, based on big data analysis (Brzustowicz, 2023; Guo et al., 2024a). In contrast, traditional paper-based catalog searches or standard database searches in libraries fall short in terms of efficiency and convenience. This has led modern users to increasingly rely on digital channels rather than visiting physical libraries, resulting in sustained pressure on the decline in physical library visitation rates.

2.2. The Breakthrough of AI to the Inherent Boundaries of Librarian’s Role

Artificial intelligence technology is transforming the professional role and responsibilities of librarians (Guo et al., 2024b; W. Li et al., 2024). In the past, librarians primarily handled foundational tasks such as cataloging and retrieving documents. Now, these tasks are increasingly being replaced by AI technologies such as intelligent algorithms, automated classification systems, and knowledge graphs (Fu & Shao, 2024). This technological transformation is driving a shift in the librarian’s role from that of a “document manager” to a “knowledge service designer.”

In terms of service models, user needs have shifted from simply accessing information to requiring knowledge discovery and innovation support (Rathod, 2025a; Zhao et al., 2023). This necessitates librarians mastering new technologies such as data mining and knowledge graph construction, positioning them as “knowledge engineers” bridging information resources with user needs. In terms of value positioning, after AI takes over standardized services, librarians’ work focus shifts to areas requiring professional judgment, such as information literacy education and digital ethics guidance. In terms of collaborative relationships, the new work model features “AI handling the technical execution layer, while librarians lead the value decision-making layer.” For example, in academic support services, AI can quickly generate draft literature reviews, while librarians are responsible for professional tasks such as academic integrity reviews (Ren et al., 2024). In the future, the core competitiveness of librarians will primarily manifest in three areas: the ability to understand the boundaries of technology application, the ability to integrate interdisciplinary knowledge, and the judgment to uphold knowledge ethics in an algorithmic society. Overall, AI technology has elevated the professional value of librarians, transforming them from information intermediaries into guardians and leaders of knowledge civilization.

2.3. Iterative Evolution of AI Replacement and Human–Machine Symbiosis

The application of artificial intelligence technology in the library field has shown clear stage-specific characteristics, evolving from simple replacement to deep collaboration. In the initial stage, AI mainly replaced repetitive and standardized tasks in library work, such as automated cataloging and intelligent retrieval. The replacement effect in this stage significantly improved work efficiency, but also raised concerns about job replacement. With technological development, the relationship between humans and machines has gradually evolved toward collaborative symbiosis, forming a more constructive mode of collaboration.

At the technical operational level, AI systems are responsible for basic tasks such as data processing and information retrieval, while librarians focus on algorithm optimization and system maintenance. At the knowledge service level, AI provides preliminary literature analysis and knowledge recommendations, and librarians conduct in-depth knowledge organization and professional guidance based on this. At the decision-making level, AI outputs data analysis results, and librarians are responsible for value judgments and ethical reviews.

Human–machine collaboration will evolve to a deeper level. AI technology will continue to advance, achieving breakthroughs in areas such as semantic understanding and knowledge reasoning. Librarians will need to continuously enhance their digital literacy and interdisciplinary skills to adapt to new collaborative requirements. The key is to establish a dynamic balance in collaborative mechanisms, leveraging AI’s technical advantages while maintaining human dominance in areas such as value judgment and innovative thinking. This iterative evolution process is fundamentally a deep integration of technology and humanities, with the ultimate goal of building a more efficient, intelligent, and human-centered modern knowledge service system.

3. Role Reinvention: Transformation from Knowledge Keeper to Intelligent Collaborator

3.1. Intelligent Resource Architects: Builders of Knowledge Ecosystems

The role of librarians has gradually shifted from traditional document preservation to knowledge services and digital ecosystem construction. The author believes that the transformation of the librarian role can be divided into five stages (as shown in Table 1), with significant changes in the technological drivers and core competency requirements at each stage.

Table 1.

Charting the Changing Role of Librarians in the Face of Technological Leapfrogging.

In the paper age, the core responsibilities of librarians were document preservation and manual cataloging, relying on printing technology and classification systems to organize resources. With the advent of digitization, the widespread use of computers and OPAC systems shifted the role of librarians to that of digital resource navigators, with card-based searches replaced by database queries, greatly improving efficiency. In the Internet age, search engines and electronic resource platforms further expanded the boundaries of library services, with librarians upgrading from reference consultants to information literacy educators, meeting user needs through online teaching and embedded services.

In the age of big data and AI, librarians are no longer limited to managing loans (Ma & Xu, 2020). Instead, they use data analysis tools and recommendation algorithms to mine user behavior, becoming digital curators and knowledge analysis experts to provide personalized services. In the metaverse/Web 3.0 phase, technologies such as blockchain and VR/AR are driving the transformation of librarians into virtual knowledge ecosystem builders. They need to master skills such as digital twin library design and NFT resource management to extend physical services into virtual spaces.

This indicates a shift in the core competencies of librarians from “resource management” to “knowledge services” and then to “ecosystem building.” Technology is not only a tool, but also a key force in reshaping professional roles. In the future, librarians will need to continuously adapt to technological changes and play a more proactive role in the convergence of virtual and real knowledge environments.

3.2. Data Literacy Mentors: Nurturers of Digital Citizenship

As users’ information literacy improves, their anxiety about information overload is also growing, and they urgently need professional assistance to establish effective cognitive frameworks within the vast sea of information. To address this need, libraries at universities both domestically and internationally have launched various data literacy training programs (F. Liu & Wu, 2023). For example, Zhejiang University Library’s “Algorithm Literacy Workshop” and Tsinghua University Library’s “Digital Literacy Workshop” are dedicated to enhancing users’ research data management capabilities. Peking University Library has launched the “Mastering Generative AI-Innovation-Empowered Practical Workshop,” while Princeton University Library is enhancing faculty and students’ AI application capabilities through its “Generative AI” LibGuid Workshop.

At the technical application level, librarians need to master tools such as natural language processing, machine learning, and data visualization to optimize search systems, improve resource recommendation mechanisms, and present knowledge association networks. The “Shangtu Discovery” system of the Shanghai Library is a typical example. This system integrates tens of millions of literature resources and constructs an intelligent knowledge network. In addition, “Xinhua AI Academic Research Assistant” provides efficient knowledge services for scholars and scientific research institutions, promoting the improvement of academic research quality and efficiency.

Faced with the challenge of information overload, the role of librarians has shifted from simply providing information to cultivating data literacy (Poley et al., 2025). This transformation requires them to break away from traditional service models and leverage smart technologies to expand the value of their services in order to meet the demands of the digital age.

3.3. Human–Computer Collaborative Supervisors: Governors of Intelligent Systems

In intelligent service systems, the role of librarians has expanded to include algorithm training, quality control, and ethical oversight. They must continuously evaluate the fairness of recommendation algorithms based on AI review frameworks and correct potential cultural biases. At the core of this transformation is the conversion of professional knowledge into a system of rules that can be executed by machines.

Human–machine collaboration has become a key component of knowledge services, with librarians assuming the role of “human–machine collaboration supervisors” to ensure that AI systems understand the knowledge logic of specialized fields. For example, the University of California Library’s intelligent consultation system has improved the accuracy of AI responses to academic inquiries through librarian-provided knowledge inputs. Shanghai Library’s “Genealogy Knowledge Service Platform” integrates over 100,000 genealogy catalogs from 630 institutions worldwide, using linked data technology to achieve structured connections and generate visualizations such as timelines, geographic heat maps, and family trees, driving innovative applications of traditional cultural resources.

Librarians need to break through traditional functional boundaries and transform themselves from single service providers into cross-disciplinary collaborators and “connectors.” New forms such as virtual librarians and metaverse libraries will transcend physical space limitations and achieve human–machine symbiosis. This transformation is not only necessary for professional development, but also key to ensuring that libraries continue to play their role as public spaces for knowledge in the digital intelligence age.

4. Value Reconfiguration: New Coordinates in the Knowledge Services Ecosystem

4.1. Reconstructing the Core Competencies of Librarians

In the wave of digital transformation, the core competitiveness of librarians is undergoing a systematic restructuring, which manifests itself in three dimensions: technical capability, service model, and value positioning. Modern librarians need to master digital skills such as data mining, knowledge graph construction, and optimization of intelligent retrieval systems, transitioning from traditional literature management to intelligent data governance, and evolving from “book managers” to “knowledge engineers.” The service model dimension is undergoing an upgrade from passive response to proactive empowerment, with core capabilities manifested in conducting embedded information literacy education, cultivating users’ digital critical thinking, providing personalized knowledge recommendation services, building disciplinary knowledge service systems, and deeply engaging in teaching and research processes. The value positioning dimension is expanding from resource managers to cultural leaders. Through planning digital humanities projects, promoting community knowledge co-creation, and participating in open science practices, librarians are redefining their unique value in the knowledge society (J. Jia & Zhang, 2024). The essence of this core competency reconstruction is that librarians, while maintaining their public service nature, are rebuilding their professional authority in the intelligent era through technological empowerment and service innovation.

4.2. The Catalytic Effect of Digital Humanities

The catalytic effect of digital humanities manifests itself in the integration of technological innovation and humanistic spirit, driving the transformation of knowledge service models. Technologies such as big data and artificial intelligence have expanded the boundaries of knowledge acquisition, while immersive technologies such as VR/AR have enhanced the humanistic experience. This technological empowerment reinterprets humanistic values through digital logic, enabling cultural connotations to be expressed in interactive forms. For example, in the field of ancient book digitization, AI technology has enabled text recognition and scene restoration.

The catalytic effect has prompted a transformation in the role of knowledge service providers. Librarians have evolved from knowledge guardians to intelligent collaborators, with their functions expanding into areas such as data analysis and digital storytelling. This requires practitioners to master technical tools such as Python and GIS, while also possessing humanistic interpretation skills, thereby establishing professional advantages in the intersection of technology and the humanities.

This is also reflected in the diversification of service scenarios. Innovative practices such as the metaverse library and urban memory database break the limitations of physical space and create a cultural environment that combines the virtual and the real. These practices expand the scope of knowledge services and strengthen the effectiveness of knowledge dissemination through participatory models.

It is worth reflecting on the fact that the development of digital humanities faces the challenge of balancing technical rationality and humanistic values. Algorithm recommendations must balance efficiency and diversity, data visualization must balance accuracy and aesthetics, and intelligent services must be both precise and maintain a humanistic touch. This contradiction drives the deep integration of technology and humanities.

The future development of digital humanities should adhere to a people-centered approach, promoting mutual advancement between technology and humanities to enhance the value of knowledge services.

4.3. Humanistic Compensation of Affective Computing

As an important branch of artificial intelligence, affective computing simulates human emotions through algorithms. While achieving technological breakthroughs, it also plays a vital role in addressing the lack of humanistic elements in the digitalization process. Its core value lies in reconstructing the emotional dimension of human–computer interaction, thereby ensuring that technological development remains grounded in humanistic care.

At the knowledge interaction level, affective computing systems use technologies such as speech recognition and micro-expression analysis to perceive users’ emotional states, breaking through the limitations of traditional mechanical interaction. Typical applications include: AI in the education field uses real-time analysis of learners’ expressions to adjust teaching strategies, achieving a shift from efficiency-oriented to experience-optimized teaching; library service robots assist users in social training, balancing algorithm efficiency and user autonomy in intelligent recommendation systems.

In terms of value creation, affective computing has driven knowledge service institutions to achieve transformation and improvement across three dimensions. Service boundaries have been expanded through constructing knowledge graphs and developing digital humanities projects, thereby enhancing the value of information resources; service content has been deepened by expanding from basic lending services to comprehensive, full-cycle services including information literacy education; and social functions have been strengthened through projects like cultural IP incubation and community memory excavation to activate local cultural ecosystems. For example, the university AI incubator project not only enhances librarians’ digital skills but also meets the diverse needs of the community, forming a model of synergistic development between “technology–knowledge–humanities.” The intrinsic value of this technology lies in breaking through the limitations of instrumental rationality and establishing a dynamic balance between technological application and humanistic needs.

5. Challenges and Countermeasures

Artificial intelligence technologies (such as AI recommendation systems, automated retrieval, and cloud-based resource sharing) have improved service efficiency but have also reshaped the professional role of librarians, leading to a crisis of identity (X. Zhang & Lei, 2024). Under the dominance of technology, how can librarians redefine their value, maintain professional authority, and achieve professional autonomy in human–machine collaboration? In the data-driven era, their role must transcend that of traditional document managers to become builders and guardians of the data ecosystem (Rjsé et al., 2023). Overall, the challenges posed by AI technology to the librarian profession are concentrated in four dimensions: role ambiguity (S. Wang et al., 2025a), skill gaps (Zhou & Zhang, 2025), human–machine collaboration dilemmas (S. Wang et al., 2025b), and organizational change resistance (Q. Li et al., 2025). The specific details are described in the following table (Table 2). A systematic reconstruction of capabilities is urgently needed to achieve sustainable professional development.

Table 2.

Key Challenging Dimensions of AI for the Librarianship Profession.

Librarians need to break through traditional competency frameworks and systematically rebuild their competencies in the following three dimensions. They need to upgrade their technical knowledge and master emerging digital technology applications; promote adaptive organizational change and establish flexible and efficient working mechanisms; and build a sustainable lifelong learning ecosystem to ensure continuous professional development. These three aspects support each other and together constitute a competency paradigm for librarians that meets the requirements of the new age.

5.1. Paradigm Shift in Technology Perception

Librarians must transcend the cognitive limitation of viewing technology as a mere tool and adopt a digitally native mindset; master data cleaning and annotation techniques to transform unstructured documents into computable resources; understand the mechanisms of algorithmic recommendations and incorporate knowledge-based ethical judgments into intelligent push notifications; and utilize digital twin technology to construct virtual learning spaces, extending physical venue services into the metaverse dimension. This shift in thinking requires librarians to simultaneously enhance their technical understanding, digital service capabilities, and technical ethical judgment (Kwak & Noh, 2021).

Librarians’ technical understanding must go beyond the application of individual tools and build a three-dimensional cognitive system of “technology-service-humanities.” At the technical level, they need to master integrated technology stacks such as intelligent retrieval and digital resource management, understand the underlying logic of APIs and blockchain, and achieve deep adaptation between technology and scenarios. At the data level, they need to shift from traditional information management to data-driven models such as user behavior analysis and knowledge graph construction, and use data cleaning and visualization to uncover hidden needs. In terms of service, they must balance technological efficiency with ethical risks, establish human–machine collaboration mechanisms in intelligent recommendation and consultation services, and prevent algorithmic bias and information silos.

The digital service capabilities of librarians are undergoing a systemic transformation, with the core shift being from single-technology operations to a composite capability framework. At the foundational level, librarians must master data analysis, digital resource management, and smart tool operation capabilities, such as using Python to clean heterogeneous data and leveraging semantic web technology to optimize resource indexing. At the collaborative level, they should build cross-system coordination capabilities, integrate data interfaces between library management systems and smart city platforms, and achieve intelligent matching of reader behavior data with public service resources. At the innovation layer, the ability to design digital service ecosystems is required, such as building digital twin libraries and developing AR navigation and other immersive services to redefine knowledge dissemination scenarios. It is worth noting that capability upgrades must incorporate ethical dimensions.

As key gatekeepers of technological ethics, establishing ethical review mechanisms in data collection and knowledge services, and developing a technical governance toolkit that includes privacy impact assessments (PIAs) and algorithm transparency reports, are essential for balancing convenience and privacy rights in digital services (Tsekea & Mandoga, 2024). For example, Georgetown University’s MDI Scholar Program not only enhances students’ technical capabilities but also increases their sensitivity to ethical issues, encouraging further reflection on ethical frameworks in research. As highlighted in the American Library Association (ALA)’s “State of America’s Libraries 2024” report, librarians not only possess the ability to utilize AI technology but can also lead the ethical application of AI in the information field (American Library Association [ALA], 2025). As defenders of data privacy, librarians must establish strict authorization mechanisms in scenarios such as user behavior tracking and personalized services to prevent big data analysis from being misused as a surveillance tool. For example, when using algorithmic recommendations for resources, transparent selection mechanisms should be designed to allow readers to decide whether to accept data profiling. At the technical application level, librarians must be vigilant against algorithmic bias eroding knowledge equity.

5.2. Agile Reconfiguration of Organizational

The agile restructuring of organizational structures is not merely a matter of structural adjustments, but also an upgrade in service philosophy. Traditional pyramid-shaped structures, with their rigid departmental divisions and slow decision-making processes, are ill-equipped to respond to rapidly changing user needs. As a result, library organizational structures are gradually evolving toward a “modular cell structure,” emphasizing flexibility, collaboration, and innovation to adapt to new paradigms in knowledge services.

Traditional library departments (such as acquisitions and cataloging, circulation, and reference services) often suffer from issues such as rigid functions and barriers to collaboration (Cai et al., 2025). In contrast, new organizational structures are centered around project-based teams, such as digital humanities services, information literacy education, and smart reading promotion teams, which can dynamically adjust their personnel configurations according to task requirements. This model draws on the “agile team” concept used by Internet companies, enabling libraries to respond quickly to diverse needs such as research support, community services, and digital literacy training. For example, when undertaking a digital humanities project, a cross-disciplinary team can be temporarily formed comprising data librarians, subject matter experts, and technical developers to ensure the precision and innovation of knowledge services.

The restructuring of organizational structures imposes new demands on the capabilities of library staff, specifically requiring a “T-shaped capability structure” that maintains professional depth in vertical fields (such as literature management and intelligence analysis) while also possessing horizontal collaboration capabilities (such as project management and user experience design). The introduction of AI technology has further reinforced this need, requiring librarians to master tools such as intelligent recommendation algorithms, knowledge graph construction, and digital twins to enhance service efficiency (Jin et al., 2025). For example, by integrating borrowing records and research behavior data through a data middleware platform and combining AI analysis to generate reader profiles, libraries can achieve personalized knowledge recommendations, evolving from passive response to proactive service.

5.3. Lifelong Learning Skills

As knowledge updates accelerate and technology undergoes iterative upgrades, traditional professional skills are no longer sufficient to meet the demands of smart services. Librarians must proactively master emerging skills such as data analysis, AI tool applications, and digital humanities, while also cultivating critical thinking and innovative capabilities. Libraries should establish systematic learning mechanisms, such as micro-course systems, skill sandbox laboratories, and cross-institutional exchange platforms, to help librarians continuously update their knowledge structures. Only through lifelong learning can librarians effectively master intelligent technologies and play a greater role in knowledge curation, smart services, and cross-border collaboration, truly achieving a role transition from resource managers to knowledge innovation leaders.

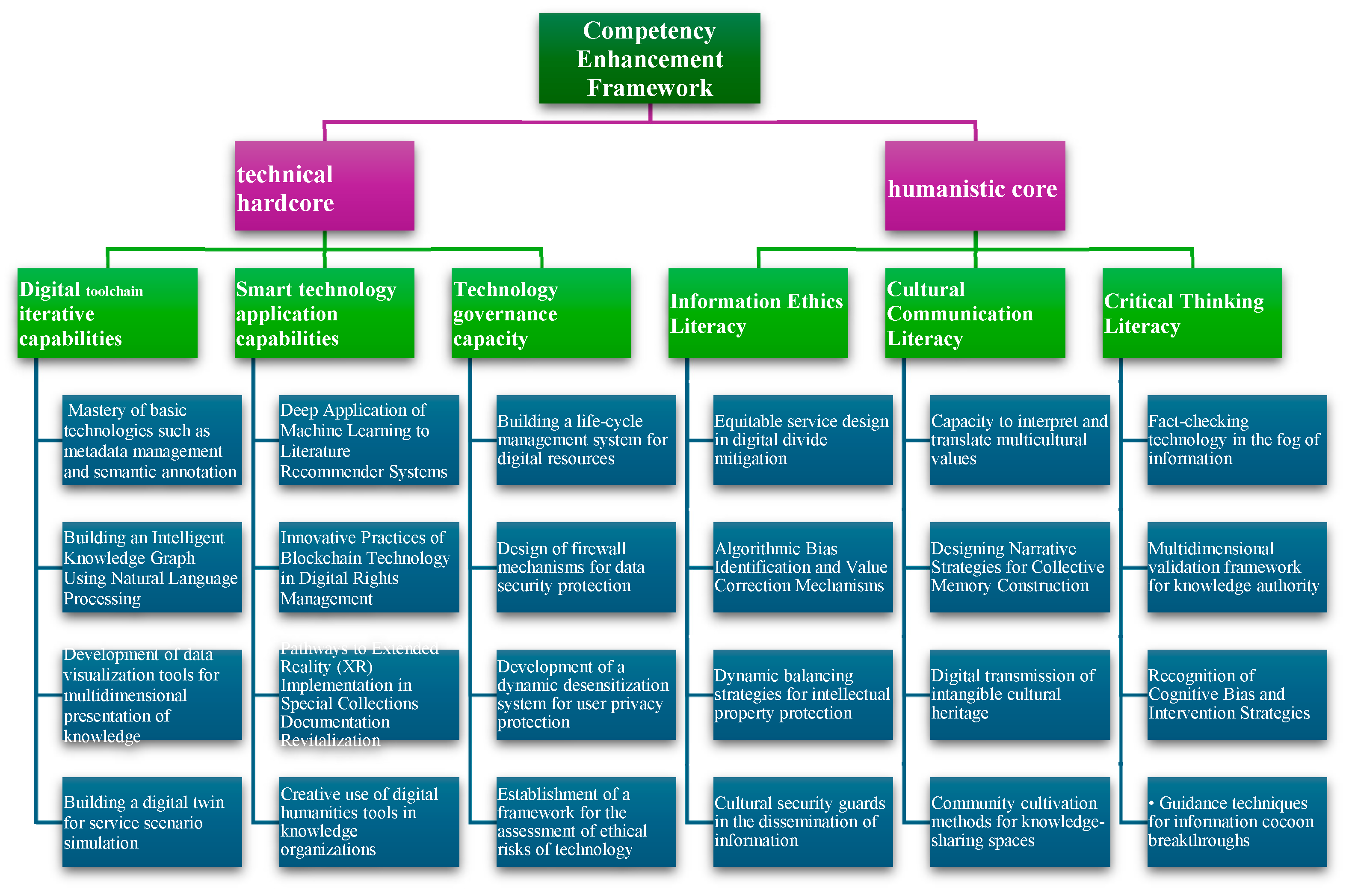

5.3.1. Collaborative Librarian Competency Framework

Based on the existing references (Bai et al., 2025; Huang, 2025; Y. Liu & Xu, 2025; Wei et al., 2025), the author proposes that librarian competency development should follow a clearly defined, synergistic framework (Figure 1). At the technical level, the focus must move beyond basic operations to building a digital skill stack centered on data intelligence (AI, data analytics) and immersive technologies (XR, digital twins), thereby solidifying the foundation for intelligent services. On the humanities front, emphasis should be placed on cultivating critical thinking and ethical awareness. Through information ethics education, digital humanities methodologies, and interdisciplinary learning, librarians can enhance their capabilities in revitalizing cultural heritage and breaking through information silos, thereby upholding a people-centered service ethos.

Figure 1.

Competency Enhancement Framework Schematic.

Future professional development for librarians should therefore center on a composite competency framework that integrates technology and the humanities. By fostering a continuous interaction between digital tools and humanistic values, this approach will ultimately drive the transformation of librarians into facilitators of knowledge services and cultural innovation.

5.3.2. Supply-Side Reforms in Learning Ecology

To build a three-tier learning support system, it is necessary to establish a systematic learning support network from the individual to the industry level to promote knowledge updating and resource sharing (Sun, 2025; Wu, 2022). (1) Micro-level: Implementation of personalized learning paths and digital badge certification system. The University of Pennsylvania Libraries and Washington University in St. Louis Libraries have built a professional development system based on digital badge certification to develop personalized learning programs for librarians and effectively improve their information literacy and professional skills. The National Library Publishing House has developed a “knowledge service platform” that realizes the visual management of learning outcomes through microcourses and online assessment mechanisms. As a supporting textbook for continuing education, “Fourteen Lectures on Librarian Competency Enhancement” systematically covers 14 core areas, such as ancient book conservation and emergency management. It is recommended to design learning paths based on job competency models, analyze librarian skill gaps and recommend training content with the help of artificial intelligence technology. It is worth noting that George Mason University Library has created an AI academic salon led by librarians, formed professional communities and AI working groups, and regularly discusses the innovative application of AI technology in teaching and research. Duke University’s “Bass Connection” program has successfully built an interdisciplinary collaboration model, breaking through professional barriers to form a research team to carry out innovative research. (2) Meso-layer: building an inter-library MOOC alliance and vocational skills sharing platform. Through the integration of high-quality resources from universities and publishing institutions, a standardized curriculum system has been established. The Chinese Library Association promotes the sharing of typical cases through the mechanism of academic symposiums, and promotes cross-regional synergistic development. OCLC’s WebJunction platform has formed a global librarian skills exchange community, supporting the distributed knowledge management model. (3) Macro-level: Promote the synergistic development of continuing education credit banks and higher education institutions. The Shenzhen Skills Bank has implemented the “Technician Excellence” program, which integrates vocational training credits into the academic education system through cooperation with higher education institutions. International experiences such as the Hong Kong Qualifications Framework (HKQF) in China, the Qualifications and Credit Framework (QCF) in the United Kingdom, the National Credit Bank System in South Korea, and the European Credit Transfer System (ECTS) provide institutional safeguards for the accumulation and transfer of lifelong learning outcomes.

5.3.3. Cultivating Professional Resilience in Librarians

Against the backdrop of technological revolution and social transformation, the cultivation of professional resilience among librarians has shifted from passive adaptation to proactive leadership, becoming a critical factor in sustaining professional vitality and the sustainability of the knowledge ecosystem (Du, 2025; Hong et al., 2025; D. Jia et al., 2025; T. Li et al., 2025; S. Wang et al., 2025c; Yuan et al., 2025; M. Zhang, 2025). This paper presents a six-dimensional framework comprising “cognition—capability—service—organization—technology—ethics,” utilizing 18 key capability elements and tools to systematically enhance librarians’ adaptability, foresight, and innovative capacity (Table 3). The cognitive dimension reinforces professional identity and lifelong learning awareness; the competency dimension focuses on interdisciplinary skills and innovative thinking; the service dimension emphasizes user needs insight and personalized responses; the organizational dimension optimizes collaborative mechanisms and resource integration; the technology dimension deepens digital tool application and data literacy; and the ethical dimension emphasizes information equity and professional responsibility. This multi-dimensional framework not only helps librarians adapt to industry changes but also drives their transformation from traditional service providers to knowledge navigators. In the future, it will be necessary to refine evaluation indicators based on empirical research and build a dynamically optimized resilience cultivation ecosystem to maintain the diversity, fairness, and sustainability of knowledge services in the intelligent age.

Table 3.

Framework for Cultivating Librarians’ Professional Resilience.

6. Conclusions and Outlook

The predicament faced by librarians reflects the widespread crisis of occupational alienation in a technological society. The key to overcoming this predicament lies in rejecting “technological determinism,” actively engaging in the design logic of technology, and shifting professional autonomy from “adapting to technology” to “mastering technology,” ultimately achieving the symbiosis of instrumental rationality and value rationality (Rathod, 2025b). The true value of librarians does not lie in possessing knowledge carriers, but in creating the potential for knowledge flow (Yang, 2024). When AI takes over the mechanical labor of information processing, human intelligence is freed to engage in higher-dimensional value creation: constructing knowledge association networks, cultivating critical thinking, and safeguarding information ethics. The smart library of the future will no longer be a cold digital warehouse, but a knowledge ecosystem built through human–machine collaboration, with librarians serving as “smart navigators” guiding humanity to find beacons of knowledge in the flood of information.

The pressure brought by AI is essentially a catalyst for professional value upgrading. Librarians’ advantages lie in their comprehensive understanding of the knowledge ecosystem, their deep insight into user needs, and their commitment to social responsibility. By actively embracing technology and redefining the core of their services, librarians will become the key designers of “smart knowledge services” in the AI era, establishing a new balance between algorithmic logic and humanistic care. Future smart libraries will present a symbiotic landscape where “AI processes information, and librarians create knowledge.” This transformative process is both a challenge and a historic opportunity for the librarian profession to achieve leapfrog development. The transformation practices of librarians aim to demonstrate that human professional groups, after undergoing value reconstruction, can indeed become pioneers in the technological era, carving out new civilizational forms within the pressure field of machine intelligence and human wisdom. This exploration will provide a transferable paradigm reference for professional fields facing AI disruption.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, all authors; Methodology, all authors; Writing—original draft, J.Z.; Writing—review and editing, J.L.; Funding acquisition, J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41977411); and Siping City Science and Technology Development Program Project (2023031).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- American Library Association [ALA]. (2025). Available online: https://www.ala.org/news/state-americas-libraries-report-2025 (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Bai, R., Zhang, X., & Niu, X. (2025). Research on the current situation and development of future learning center construction in university libraries under the digital environment. Library and Information Service, 69(7), 90–101. [Google Scholar]

- Brzustowicz, R. (2023). From ChatGPT to CatGPT: The implications of artificial inteligence on lilbrary cataloging. Information Technology and Libraries, 42(3), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y., Zhou, Q., & Niu, J. (2025). The 15th five-year plan of university libraries: Core elements and development paths. Library Journal, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Du, J. (2025). Research on the artificial intelligence literacy education services in American university libraries and its implications. Library and Information Service, 69(14), 135–148. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, C., Chen, J., Chen, X., & Chi, R. (2025). The voice of artificial intelligence: A social semiotic perspective on AI perception of library profession. Library Tribune, 45(2), 72–81. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, A., & Shao, B. (2024). A study on the competency requirements and transformation directions for technical librarians in university libraries. Library Theory and Practice, (5), 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y., Feng, S., Kou, X., & Liu, Z. (2024a). Librarians in the context of generative AI: Roles, skills, and approaches. Library and Information Service, 68(13), 69–77. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y., Ma, H., Zhang, X., & Feng, S. (2024b). ChatGPT empowers library knowledge services: Principles, scenarios, and approaches. Library Development, 3, 60–68. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, W., Wei, X., & Zhao, Q. (2025). Exploration on the implementation path and guarantee mechanism of artificial intelligence literacy education in university libraries. New Century Library, (5), 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H. (2025). Research on the design and development path of data governance capability model for public libraries in the digital age. Library, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, D., Zhao, M., & He, Y. (2025). A review of research on foreign public library services for resilient cities. Library and Information Service, 67(10), 139–147. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, J., & Zhang, G. (2024). Metadata core competencies of librarians from the perspective of smart library construction. Journal of Library Science in China, 50(2), 56–69. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, J., Pan, J., Zhang, Z., & Huang, C. (2025). AI-driven paradigm shift and innovation pathways for future library. Journal of Library Science in China, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kwak, W., & Noh, Y. (2021). A study on the current state of the library’s AI service and the service provision plan. Journal of Korean Library and Information Science Society, 52(1), 155–178. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q., Zhao, S., Zhang, M., & Du, P. (2025). Strategies for Al literaey cultivation in university libraries from the perspective of aclivity theory. Research on Library Science, (4), 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T., Wang, Y., & Liu, S. (2025). Library user relationship management: Evolution, realistic challenges and development path. Journal of Academic Libraries, 42(6), 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W., Cai, Y., & Wang, R. (2024). Reshaped role and strategic integration of academic libraries driven by AI. Library Journal, 43(11), 50–60. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F., & Wu, Z. (2023). Analysis and application suggestions on digital narrative phenomenon of cultural heritage. Digital Library Forum, 19(11), 46–52. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y., & Xu, X. (2025). Artificial intelligence+’enabling smart library construction: Theoretical logic and practical concepts. Library Development, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, S., & Xu, Y. (2020). Rational thinking of artificial intelligence applying in library. Library, (4), 44–51. [Google Scholar]

- Poley, C., Uhlmann, S., Busse, F., Jacobs, J. H., Kähler, M., Nagelschmidt, M., & Schumacher, M. (2025). Automatic subject cataloguing at the German national library. LlBER quarterly. The Journal of the Association of European Research Libraries, 35(1), 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathod, M. S. G. (2025a). The impact of artificial intelligence on libraries: A statistical analysis. International Journal of Research in Library Science (IJRLS), 11(2), 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathod, M. S. G. (2025b). The rise of smart libraries: Integrating IoT, cloud services, and AI for next-gen learning spaces. International Journal of Research in Library Science, 11(2), 211–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H., Li, J., & Li, X. (2024). Research on the path to improve the service of subject librarians based on competency model. Research on Library Science, (6), 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rjsé, V., Jylkäs, T., & Miettinen, S. (2023). AI enabled airline cabin services: AI augmented services for emotional values. Service design for high-touch solutions and service quality. Design Management Journal, 18(1), 100–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L. (2025). Exploring the construction of a service competency model for librarians in the AI era—An integrated analysis based on U.S. library job postings and ALA’s core competency draft. Library Development, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, Y., & Chen, J. (2025). Dual transformation under the DeepSeek wave: Technological innovation in large models and the restructuring of service paradigms in academic libraries. Journal of Academic Libraries, 43(1), 66–70. [Google Scholar]

- Tsekea, S., & Mandoga, E. (2024). The ethics of artificial intelligence use in university libraries in Zimbabwe. Frontiers in Research Metrics and Analytics, 9, 1522423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, S., & Chu, S. (2024). Crossing, integrating, and sharing: Exploring the future of the “boundaryless” library. Journal of the National Library of China, 33(5), 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S., Qian, G., Cai, C., & Song, R. (2025a). Current status and path exploration of context—Driven lnnovation in university libraries in China. Research on Library Science, (7), 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., Zeng, W., Qi, Q., Xu, L., & Yue, F. (2025b). The expansion of research topic ideas with the integration of generative ai search engines and human-computer collaboration. Documentation, Information & Knowledge, 42(4), 113–125. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S., Zhu, Y., & Wang, N. (2025c). Libraries empower the digital transformation of university education in the era of artificial intelligence: The roles, challenges, and pathways. Journal of Academic Libraries, 43(3), 65–77. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X., Liang, M., Hou, X., & Song, N. (2022). Intelligent computing of cultural heritage: A case study of European time machine project. Journal of Library Science in China, 48(1), 62–76. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. (2023). Research on librarians, librarian based services and their transformations. Library, (10), 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Q., Xu, T., Tu, J., Cai, J., & Shi, D. (2025). Practical exploration of resource-service integration in university libraries based on the synergy of literature, space, and human resources. Journal of Academic Libraries, 43(3), 56–64. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D. (2022). Discussion on libraries’ knowledge ecosystem construction and its application from the perspective of ‘Metaverse’. Journal of Library and Information Science, 7(4), 30–35. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X. (2024). Promotion strategies for digital scholarship services capacity of university librarians. Library Work and Study, (3), 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y., Lu, J., & Chen, Y. (2025). Librarians’ digital resilience: Connotation characteristics, logical models, and improvement strategies. Library and Information Service, 69(8), 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Y., Yang, M., & Hou, L. (2024). Practice and reflection on developing modernization-oriented competencies of academic librarians-taking the fudan university library as an example. Journal of Academic Libraries, 42(4), 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M. (2025). Research on the practice of AI literacy education in university libraries in China. Library and Information Service, 69(18), 98–108. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X., & Lei, M. (2024). Challenges and countermeasures for library services in the context of artificial intelligence. Library & Information, (6), 113–121. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X., Song, X., Wang, P., Fan, M., & Ma, H. (2023). A new exploration on the construction of normalized model for improving librarians’ ability-taking Shandong University Library as an example. Journal of Academic Libraries, 41(3), 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X. M., & Zhang, C. (2025). Integration and challenges: Application of multifunctional AI robots in smart library development. Library Development, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).