Comments on New Integrative Photomedicine Equipment for Photobiomodulation and COVID-19

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Definition of Laser Acupuncture

“Photonic stimulation of acupuncture points and areas to initiate therapeutic effects similar to those of needle acupuncture and related therapies along with the benefits of PhotoBioModulation (PBM).”

3. COVID-19: TCM, Acupuncture and Photonics

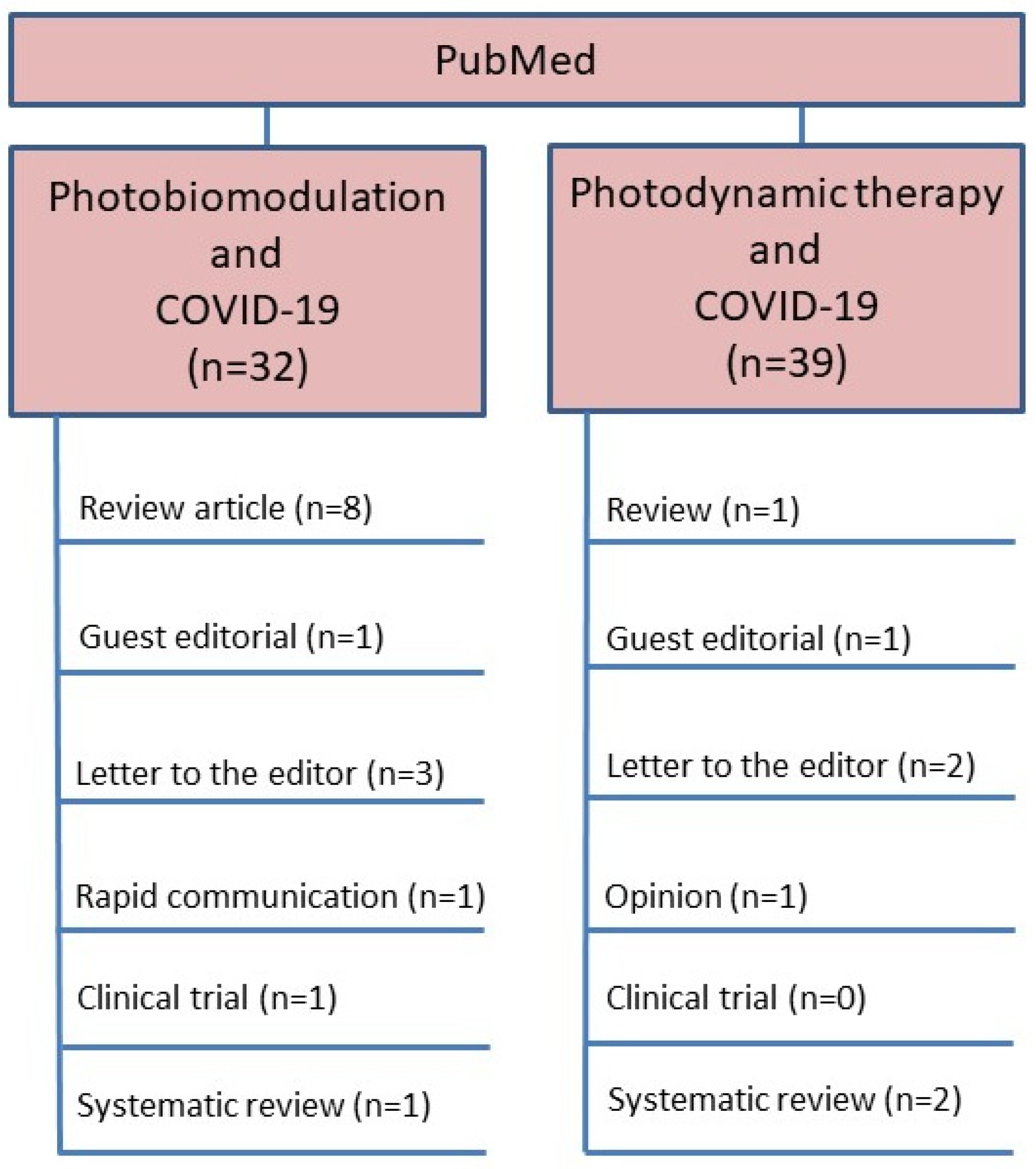

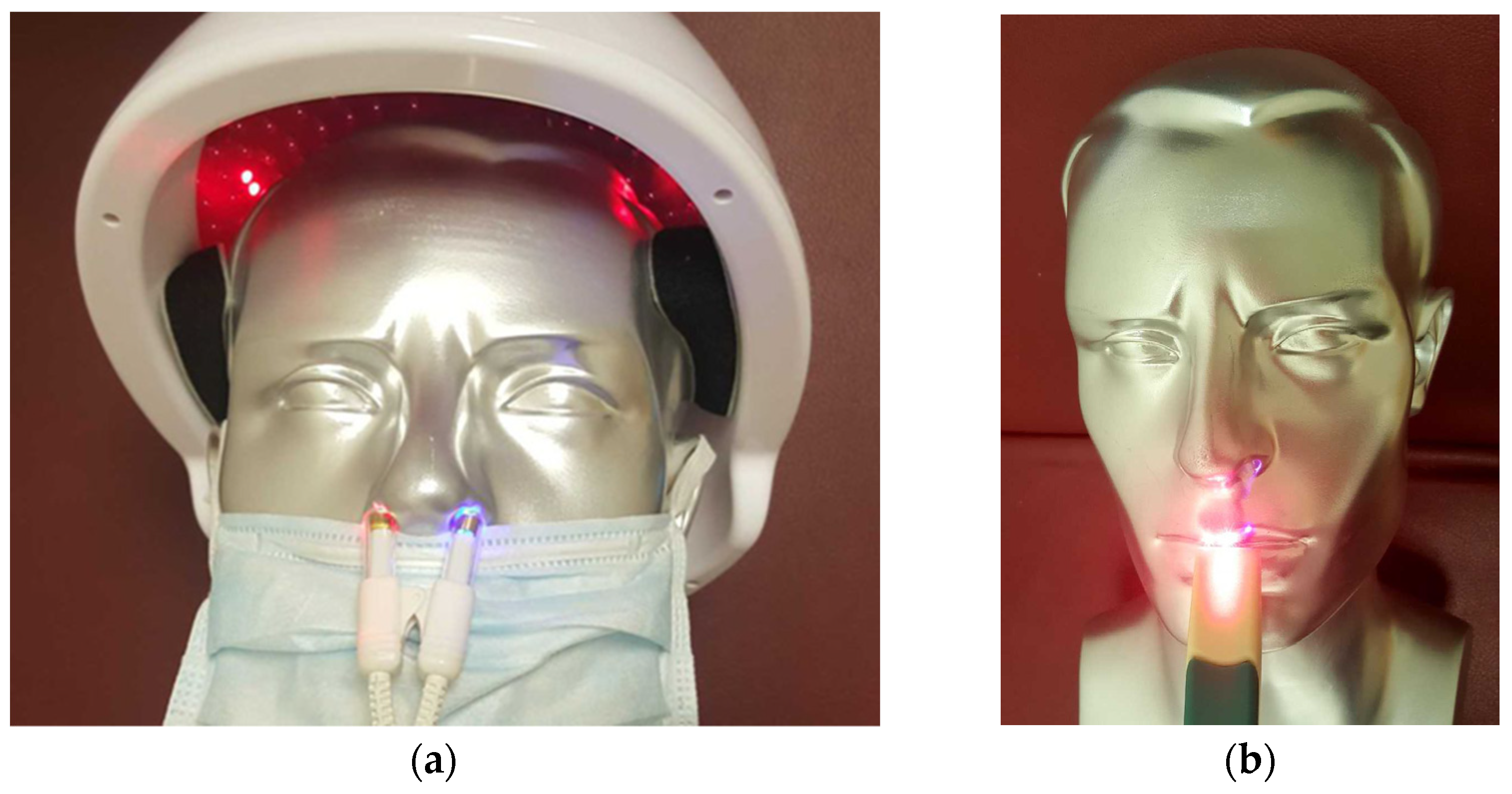

4. COVID-19—Photonics: Effectiveness of Integrative Photomedicine?

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Körbler, J. On the History of the Development of Sunlight Treatment. Hippokrates 1967, 38, 145–150. (In German) [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Litscher, G. History of Laser Acupuncture: A Narrative Review of Scientific Literature. Med. Acupunct. 2020, 32, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.M. Historical Origin of Jiu Tangshu Biography of Sun Simiao. Zhonghua Yi Shi Za Zhi 2012, 42, 264–271. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Einstein, A. On the Quatum Theory of Radiation. Mitt. Phys. Ges. Zürich 1916, 18, 47–62. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Bahr, F.R.; Litscher, G. Laser Acupuncture and Innovative Laser Medicine; Bahr&Fuechtenbusch Publisher: Munich, Germany, 2018; pp. 1–185. [Google Scholar]

- Forster, P.; Forster, L.; Renfrew, C.; Forster, M. Phylogenetic Network Analysis of SARS-CoV-2 Genomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 9241–9243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Coronavirus: First Case on September 13th? Available online: https://www.nau.ch/amp/news/ausland/coronavirus-mehr-als-150000-todesopfer-weltweit-65694944 (accessed on 2 June 2020). (In German).

- Litscher, G. Effectiveness of Integrated Medicine in COVID-19? Editorial. Med. Acupunct. 2020, 32, 131–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, T.E. Laser acupuncture. Continuum Omni. 1978, 1, 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Litscher, G. Definition of Laser Acupuncture and All Kinds of Photo Acupuncture. Medicines 2018, 5, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cyranoski, D. When Will the Coronavirus Outbreak Peak? Nature News. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-00361-5 (accessed on 18 February 2020).

- Litscher, G.; Liang, F.X. COVID-19 (Coronavirus Disease-19): Traditional Chinese Medicine Including Acupuncture for Relief-A Report from Wuhan, Hubei Province, China. Akupunkt. Aurikulomedizin 2020, 46, 9–10. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Valussi, M.; Antonelli, M.; Donelli, D.; Firenzuoli, F. Appropriate Use of Essential Oils and Their Components in the Management of Upper Respiratory Tract Symptoms in Patients with COVID-19. J. Herb. Med. 2021, 28, 100451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ailioaie, L.M.; Litscher, G. Probiotics, Photobiomodulation, and Disease Management: Controversies and Challenges. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Wang, S.; Tang, Z. Feasibility Analysis of Early Intervention of Moxibustion in the Prevention and Treatment of Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia. Acta Chin. Med. 2020, 19, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.; Wang, C.Z.; Hesse-Fong, J.; Lin, J.G.; Yuan, C.S. Application of Chinese Medicine in Acute and Critical Medical Conditions. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2019, 47, 1223–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litscher, G.; Litscher, D. Scientific Aspects of Innovative Laser Medicine. In Laser Acupuncture and Innovative Laser Medicine, 1st ed.; Bahr, F., Litscher, G., Eds.; Bahr & Fuechtenbusch Publisher: Munich, Germany, 2018; Volume 1, pp. 13–77. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, K.C.; Litscher, G. Robot-Controlled Acupuncture—An Innovative Step towards Modernization of the Ancient Traditional Medical Treatment Method. Medicines 2019, 6, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liang, F.X.; Litscher, G. COVID-19 (Coronavirus Disease-19): Traditional Chinese Medicine Including Acupuncture for Alleviation—A Report from Wuhan, Hubei Province in China. OBM Integr. Complement. Med. 2020, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Litscher, G. COVID-19: Effectiveness of Integrative Medicine? Akupunkt. Aurikulomedizin 2020, 46, 9. (In German) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleckenstein, J.; Füzeki, E.; Banzer, W. The Application of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM)/Acupuncture in the Therapy and Prevention of SARS-CoV-2 Infections. Dtsch. Z. für Akupunkt. 2020, 63, 70–73. (In German) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Litscher, G.; Weber, M. Research, Light, and COVID-19. Editorial. Akupunkt. Aurikulomedizin 2020, 46, 8. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Litscher, G. Can Laser Medicine and Laser Acupuncture Be Used for COVID-19? Selected Areas of the Current Scientific Literature. Editorial. OBM Integr. Complement. Med. 2020, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enwemeka, C.S.; Bumah, V.V.; Masson-Meyers, D.S. Light as a Potential Treatment for Pandemic Coronavirus Infections: A Perspective. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2020, 207, 111891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Yang, X.; Li, K.; Xie, Y.Q. Traditional Chinese Medicine for Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Treatment: Main Force or Supplement? Tradit. Med. Res. 2020, 5, 62–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, A.; Velásquez, S.A.; David, M.A. Can Transdermal Photobiomodulation Help Us at the Time of COVID-19? Photobiomodul. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2020, 38, 258–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekrazad, R. Photobiomodulation and Antiviral Photodynamic Therapy as a Possible Novel Approach in COVID-19 Management. Photobiomodul. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2020, 38, 255–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, A.B.; Lima, C.J.; Villaverde, A.G.J.B.; Pereira, P.C.; Carvalho, H.C.; Zângaro, R.A. Photobiomodulation: Shining Light on COVID-19. Photobiomodul. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2020, 38, 395–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, A.D. Author’s Response to Ferreira: Can Transdermal Photobiomodulation Help Us at the Time of COVID-19? An Update. Photobiomodul. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2020, 38, 328–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, M.V.L. Response to: Can Transdermal Photobiomodulation Help Us at the Time of COVID-19? Photobiomodul. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2020, 38, 326–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litscher, G.; Litscher, D. A Laser Watch for Simultaneous Laser Blood Irradiation and Laser Acupuncture at the Wrist. Integr. Med. Int. 2016, 3, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litscher, G. Transcranial Laser Stimulation Research—A New Helmet and First Data from Near Infrared Spectroscopy. Medicines 2018, 5, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, P.; Li, T. Which Wavelength is Optimal for Transcranial Low-Level Laser Stimulation? J. Biophotonics 2019, 12, e201800173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ailioaie, L.M.; Litscher, G.; Weber, M.; Ailioaie, C.; Litscher, D.; Chiran, D.A. Innovations and Challenges by Applying Sublingual Laser Blood Irradiation in Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. Int. J. Photoenergy 2014, 2014, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, H.M.; Mehran, Y.Z.; Orthaber, A.; Saadat, H.H.; Weber, R.; Wojcik, M. Successful Reduction of SARS-CoV-2 Viral Load by Photodynamic Therapy (PDT) Verified by QPCR—A Novel Approach in Treating Patients in Early Infection Stages. Med. Clin. Res. 2020, 5, 311–325. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, M. Photodynamic Low-Level-Laser-Therapy (PDT)—New Options in Oncology. In Laser Acupuncture and Innovative Laser Medicine, 1st ed.; Bahr, F., Litscher, G., Eds.; Bahr & Fuechtenbusch Publisher: Munich, Germany, 2018; Volume 1, pp. 147–151. [Google Scholar]

- Litscher, G.; Gao, X.Y.; Wang, L.; Zhu, B. High-Tech Acupuncture and Integrative Laser Medicine. Evidence-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2012, 2012, 363467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kingsley, D.H.; Perez-Perez, R.E.; Boyd, G.; Sites, J.; Niemira, B.A. Evaluation of 405-nm Monochromatic Light for Inactivation of Tulane Virus on Blueberry Surfaces. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 124, 1017–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirshafiee, H.; Sharifi, Z.; Hosseini, S.M.; Yari, F.; Nikbakht, H.; Latifi, H. The Effects of Ultraviolet Light and Riboflavin on Inactivation of Viruses and the Quality of Platelet Concentrates at Laboratory Scale. Avicenna J. Med. Biotechnol. 2015, 7, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Faddy, H.M.; Fryk, J.J.; Watterson, D.; Young, P.R.; Modhiran, N.; Muller, D.A.; Keil, S.D.; Goodrich, R.; Marks, D. Riboflavin and Ultraviolet Light: Impact on Dengue Virus Infectivity. Vox Sang 2016, 111, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makdoumi, K.; Hedin, M.; Bäckman, A. Different Photodynamic Effects of Blue Light with and without Riboflavin on Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA) and Human Keratinocytes In Vitro. Lasers Med. Sci. 2019, 34, 1799–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhu, L.; Pan, J.; Wie, C.; Wang, H.; Xiang, R.; Zhang, J.; Wang, D. The Effectiveness of Riboflavin Photochemical-Mediated Virus Inactivation and Changes in Protein Retention in Fresh-Frozen Plasma Treated Using a Flow-Based Treatment Device. Transfusion 2015, 55, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Marco, T.; Ruiz-Alderton, D.; Bautista-Gili, A.M.; Girona-Llobera, E. Role of Riboflavin- and UV Light-Treated Plasma in Prevention of Transfusion-Related Acute Lung Injury. Transfus. Med. Hemother. 2014, 41, 172–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gwynne, P.J.; Gallagher, M.P. Light as a Broad-Spectrum Antimicrobial. Perspective Article. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keil, S.D.; Bowen, R.; Marschner, S. Inactivation of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in Plasma Products Using a Riboflavin-Based and Ultraviolet Light-Based Photochemical Treatment. Transfusion 2016, 56, 2948–2952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moghissi, K.; Dixon, K.; Gibbins, S. Does PDT have Potential in the Treatment of COVID 19 Patients? Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2020, 31, 101889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, L.D.; Blanco, K.C.; Bagnato, V.S. COVID-19: Beyond the Virus. The Use of Photodynamic Therapy for the Treatment of Infections in the Respiratory Tract. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2020, 31, 101804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, C.; Carriere, M.; Fusco, L.; Capua, I.; Regla-Nava, J.A.; Pasquali, M.; Scott, J.A.; Vitale, F.; Unal, M.A.; Mattevi, C.; et al. Toward Nanotechnology-Enabled Approaches against the COVID-19 Pandemic. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 6383–6406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.; Faustino, M.A.F. Neves MGPMS. Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy in the Control of COVID-19. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcez, A.S.; Delgado, M.; Sperandio, M.; Dantas E Silva, F.T.; Rita de Assis, J.S.; Suzuki, S.S. Photodynamic Therapy and Photobiomodulation on Oral Lesion in Patient with Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Case Report. Photobiomodul. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2021, 39, 386–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vetrici, M.A.; Mokmeli, S.; Bohm, A.R.; Monici, M.; Sigman, S.A. Evaluation of Adjunctive Photobiomodulation (PBMT) for COVID-19 Pneumonia Via Clinical Status and Pulmonary Severity Indices in a Preliminary Trial. J. Inflamm. Res. 2021, 14, 965–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupin, L.; Gratton, R.; Fontana, F.; Clemente, L.; Pascolo, L.; Ruscio, M.; Crovella, S. Blue Photobiomodulation LED Therapy Impacts SARS-CoV-2 by Limiting Its Replication in Vero Cells. J. Biophotonics 2021, 14, e202000496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekrazad, R.; Asefi, S.; Pourhajibagher, M.; Vahdatinia, F.; Fekrazad, S.; Bahador, A.; Abrahamse, H.; Hamblin, M.R. Photobiomodulation and Antiviral Photodynamic Therapy in COVID-19 Management. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2021, 1318, 517–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigman, S.A.; Mokmeli, S.; Monici, M.; Vetrici, M.A. A 57-Year-Old African American Man with Severe COVID-19 Pneumonia Who Responded to Supportive Photobiomodulation Therapy (PBMT): First Use of PBMT in COVID-19. Am. J. Case Rep. 2020, 21, e926779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litscher, G. Photobiomodulation and COVID-19: Selection of Study Designs for Possible Home Treatment—Critical Considerations. Akupunkt. Aurikulomedizin 2021, 47, 22–28. (In German) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Litscher, G.; Ailioaie, L.M. Comments on New Integrative Photomedicine Equipment for Photobiomodulation and COVID-19. Photonics 2021, 8, 303. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics8080303

Litscher G, Ailioaie LM. Comments on New Integrative Photomedicine Equipment for Photobiomodulation and COVID-19. Photonics. 2021; 8(8):303. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics8080303

Chicago/Turabian StyleLitscher, Gerhard, and Laura Marinela Ailioaie. 2021. "Comments on New Integrative Photomedicine Equipment for Photobiomodulation and COVID-19" Photonics 8, no. 8: 303. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics8080303

APA StyleLitscher, G., & Ailioaie, L. M. (2021). Comments on New Integrative Photomedicine Equipment for Photobiomodulation and COVID-19. Photonics, 8(8), 303. https://doi.org/10.3390/photonics8080303